Abstract

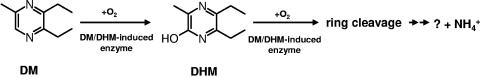

A bacterium was isolated from the waste gas treatment plant at a fishmeal processing company on the basis of its capacity to use 2,3-diethyl-5-methylpyrazine (DM) as a sole carbon and energy source. The strain, designated strain DM-11, grew optimally at 25°C and had a doubling time of 29.2 h. The strain did not grow on complex media like tryptic soy broth, Luria-Bertani broth, or nutrient broth or on simple carbon sources like glucose, acetate, oxoglutarate, succinate, or citrate. Only on Löwenstein-Jensen medium was growth observed. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain DM-11 showed the highest similarity (96.2%) to Mycobacterium poriferae strain ATCC 35087T. Therefore, strain DM-11 merits recognition as a novel species within the genus Mycobacterium. DM also served as a sole nitrogen source for the growth of strain DM-11. The degradation of DM by strain DM-11 requires molecular oxygen. The first intermediate was identified as 5,6-diethyl-2-hydroxy-3-methylpyrazine (DHM). Its disappearance was accompanied by the release of ammonium into the culture medium. No other metabolite was detected. We conclude that ring fission occurred directly after the formation of DHM and ammonium was eliminated after ring cleavage. Molecular oxygen was essential for the degradation of DHM. The expression of enzymes involved in the degradation of DM and DHM was regulated. Only cells induced by DM or DHM converted these compounds. Strain DM-11 also grew on 2-ethyl-5(6)-methylpyrazine (EMP) and 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP) as a sole carbon, nitrogen, and energy source. In addition, the strain converted many pyrazines found in the waste gases of food industries cometabolically.

Pyrazines are monocyclic heteroaromatic substances containing nitrogen atoms in positions 1 and 4 of the aromatic ring. Pyrazines are found mainly in processed food, where they are formed during dry heating processes. They are also found naturally in many vegetables, insects, terrestrial vertebrates, and marine organisms, and they are produced by microorganisms during their primary or secondary metabolism (1, 3, 36, 39). Many alkylated and methoxylated pyrazines exhibit strong odorous properties and are important flavoring compounds in a variety of food products (11, 19, 27). In addition, some pyrazines show bactericidal (20, 35) or chemoprotective (17) activities. With these properties, pyrazines have been used intensively as chemical building blocks for a series of industrial products. They are constituents of biologically active chemicals, such as antiseptics, disinfectants, herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides, as well as pharmaceuticals with different fields of application (2, 4, 29, 32, 38).

Today, more than 70 volatile alkylated pyrazines have been identified (36). Alkylpyrazines are generally found in a wide variety of foods, beverages, and food-processing plants (19, 27). Since they have very low odor thresholds (i.e., the lowest concentration at which an odor can be detected, e.g., 0.009 to 0.018 ng liter−1 air for 2,3-diethyl-5-methylpyrazine [DM]), they play a major role in the aroma of food (9, 10, 36). Among all of the alkylpyrazines, DM was identified as one of six key compounds that play a major role in the aroma of medium-roasted arabica coffee (11).

Pyrazines are considered one of the major malodorous classes of compounds in the exhaust gas stream of various food industries (26, 27). Thus, it is important to find methods to degrade these compounds before they enter the environment. There are several reports of bioremediation of heteroaromatic compounds; however, little is known about the microbial degradation of pyrazines. Very few reports have indicated transformation of pyrazines by bacterial strains. Kiener (14) showed that Pseudomonas putida, metabolizing toluene via benzyl alcohol, produces 5-methylpyrazinecarboxylic acid quantitatively from 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (2,5-DMP). This strain also transforms 2,3,6-trimethylpyrazine to 5,6-dimethylpyrazine-2-carboxylic acid. It was found that resting cells of Pseudomonas acidovorans strain DSM 4746, Alcaligenes facalis strain DSM 6269, and Alcaligenes eutrophus strain DSM 6920, grown on the appropriate pyridine carboxylic acids, were capable of oxidizing pyrazine carboxylic acid (15). Tinschert et al. (32) reported that Ralstonia/Burkholderia sp. strain DSM 6920 transformed pyrazine-2-carboxylic acid and 5-methylpyrazine-2-carboxylic acid to 3-hydroxypyrazine-2-carboxylic acid and 3-hydroxy-5-methylpyrazine-2-carboxylic acid, respectively. However, the strain could not further utilize these compounds for growth. So far, only Pseudomonas sp. strain PZ3, isolated from rat feces, has been reported to be able to grow on hydroxypyrazine (21). No other bacterial strains that can mineralize pyrazines have been isolated. In order to obtain an efficient biological treatment of air contaminated with pyrazines, it is necessary to have microbes that can efficiently degrade these compounds. Therefore, we screened for microorganisms that can utilize 2,3-diethyl-5-methylpyrazine as a representative of pyrazine compounds.

In this study, we report the isolation and characterization of a new bacterium, isolated with DM as the sole carbon and energy source. In addition, the identification of 5,6-diethyl-2-hydroxy-3-methylpyrazine (DHM) as the key metabolic intermediate allows the proposal of the first reaction in the degradation pathway. Finally, the induction of the enzymes involved in the degradation as well as the transformation or use of other pyrazines was studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Fluka, or Merck (Germany) and were of the highest purity available.

Media and culture conditions.

The mineral medium M1, which was used for the enrichment of the DM-degrading bacteria and for cultivation of the isolated bacteria, contained (per liter of deionized water) 2.5 g of K2HPO4, 1.0 g of KH2PO4, 2.0 g of (NH4)2SO4, and 0.2 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O; the pH was adjusted to 6.75. In addition, a nitrogen-free mineral medium (NF-M1), mineral medium M1 without (NH4)2SO4, was used for cultivation of the isolated strain when a pyrazine was used as a sole carbon and nitrogen source. For the isolation and cultivation of bacteria, M1 agar medium, a mineral medium M1 solidified with 1.5% agar, was used. The substrates were provided as the sole source of carbon and energy in the mineral medium. In addition to DM, pyrazine (P), 2-methylpyrazine (MP), 2,3-dimethylpyrazine (2,3-DMP), 2,5-DMP, 2,6-dimethylpyrazine (2,6-DMP), 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine (TMP), 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine (TTMP), 2-ethylpyrazine (EP), 2,3-diethylpyrazine (DEP), 2-ethyl-5(6)-methylpyrazine (EMP), acetylpyrazine (AP), and 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine (IP) were used. Soluble substrates were sterilized by filtration. All substrates were provided at 0.5 mM unless otherwise indicated. The time course of the degradation of the odorous compounds in shaking culture was measured in duplicate inoculations. Unless stated otherwise, for aerobic culture, 30 ml of liquid culture was incubated at 120 rpm and 25°C in a 100-ml serum bottle sealed with a butyl rubber septum and an aluminum crimp seal to prevent the loss of volatile substrates.

The following anaerobic procedure was used for all bacterial biodegradation tests under anaerobic conditions unless otherwise noted. A combination of 200 ml of deionized water and 100 μl of 1% stock solution of resazurin sodium salt was added to 1,000 ml NF-M1 medium. The medium was boiled until the volume was reduced to 1,000 ml. The medium was cooled on ice with continued bubbling of nitrogen. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 6.75. Next, 30 ml of the medium was transferred into 100-ml serum flasks and the headspace of the flasks was flushed with nitrogen for 10 min. To prevent the entrance of oxygen, the flasks were firmly sealed with 4-mm-thick butyl rubber septa coated with Teflon and an aluminum crimp seal. The flasks were autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min. Prior to inoculation, 1 ml of 25% Na2SO3 solution was added to the medium to remove any traces of oxygen. Inoculum (10% vol/vol) and substrate (0.5 mM) were added to the flasks via a syringe. The flasks were incubated under static conditions at 25°C. Samples were withdrawn for the determination of bacterial growth and substrate degradation. During the entire cultivation, the oxygen indicator in the culture medium remained colorless, indicating anaerobic conditions. All tests were done in duplicate.

To test for cometabolism, NF-M1 medium, containing both the substrates DM (0.5 mM) and the test compound (different pyrazine compounds, concentration of 0.5 mM), was used. The flasks were inoculated with 10% (vol/vol) of a liquid culture of strain DM-11, which had been grown on DM. Growth was followed by recording the optical density at 550 nm (OD550 nm) or total cell count regularly. The transformation of the chemicals was followed by recording the UV spectra (see “Analytical procedures”). Cometabolism experiments were performed in duplicate.

Resting-cell assays.

Cultures in the late exponential growth phase were used for preparation of resting-cell suspensions. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed three times with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.75), and resuspended in the NF-M1 medium. The OD550 nm of the resting-cell suspensions was adjusted to 15. Chloramphenicol was used in order to inhibit de novo protein synthesis of the resting cells. A filtered sterile stock solution of chloramphenicol in ethanol (34 mg ml−1) was added to the cell suspension at a final concentration of 100 μg ml−1 (this concentration was experimentally confirmed to inhibit growth of the strain DM-11 effectively) and preincubated on a shaker at 120 rpm and 25°C for 60 min before starting the experiment. Test compounds (0.5 mM) were added to the cell suspensions, and the suspensions were incubated on a shaker at 120 rpm and 25°C. At appropriate time intervals, aliquots of the cell suspensions (0.5 ml) were withdrawn and centrifuged immediately for 3 min in a microcentrifuge at full speed. The concentrations of the tested compound and of metabolites in the supernatants were determined.

To determine whether the enzyme systems responsible for the biotransformation of DM and DHM were induced or constitutively expressed, two batches of cells were prepared. For induced cells, cells were grown to the late exponential growth phase in NF-M1 containing 0.5 mM DM or DHM, respectively. For non-induced cells, cells were grown on Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) at 25°C for 2 weeks. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed three times with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.75. The washed cells were tested for their ability to transform DM or DHM in the presence of chloramphenicol.

Enrichment, isolation, and identification of DM-degrading strain.

Soil samples, biofilter materials, and liquid medium from biowashers that had been contaminated with odorous compounds were collected from various food companies in Germany. The samples were stored at 4°C until they were used. One gram of soil or 1 ml of liquid samples was added to 30 ml of M1 medium and amended with 0.5 mM DM as the sole carbon source in a 100-ml serum bottle. The bottle was sealed with a butyl rubber septum and an aluminum crimp seal to prevent the loss of DM. Bottles were shaken at 25°C and 120 rpm for 2 weeks and then subcultured weekly into fresh medium. After 5 to 10 subcultures, samples from bottles showing visible growth were analyzed for DM degradation. Samples from bottles that showed good growth and good DM degradation were spread onto M1 agar plates. DM was supplied to the plates via the gas phase in a desiccator containing DM (100 μl of DM liter−1 of the desiccator volume) and incubated at 25°C. Single colonies were separated and subcultured on fresh plates. The pure strains were tested for their ability to utilize DM as the sole source of carbon in M1 liquid medium. The strain that showed the highest activity for degradation of DM and good growth was selected and maintained routinely on an M1 agar plate supplied with the vapor of DM as a sole carbon source, with transfers every 2 months to fresh medium. Long-term storage was done at −70°C on glass embroidery beads with special cryomedium (Roti-Store Cryoröhrchen; Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), which was deposited in the strain collection of the Institute of Technical Biocatalysis, Technical University Hamburg-Harburg, Hamburg, Germany.

Scanning electron microscopy of the isolated strain was performed. Cells at the exponential phase of growth were harvested and washed with 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.75. The cells were suspended in the phosphate buffer, fixed with 5% glutaraldehyde, and incubated at room temperature overnight. Subsequently, the samples were washed with phosphate buffer and dehydrated using ethanol (20, 40, 60, 80, and absolute ethanol, 2 h each step). The dehydrated samples were subjected to critical point drying with liquid CO2 according to the standard procedure. The samples were mounted on aluminum specimen stubs by using electrically conducting carbon (PLANO, Wetzlar, Germany) and were sputter coated with a gold layer of approximately 15 nm by using argon gas as the ionizing plasma. Imaging was performed with an S-450 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a secondary electron at a 10-kV acceleration voltage and at room temperature.

The 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the isolated strain was carried out at Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ; Braunschweig, Germany) by direct sequencing of the PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene. Genomic DNA extraction, PCR-mediated amplification of the 16S rRNA gene, and purification of the PCR product were carried out as described by Rainey et al. (25). Purified PCR products were sequenced using the CEQ dye terminator cycle sequencing Quick Start Kit (Beckmann Coulter). Sequence reactions were electrophoresed using the CEQ 8000 genetic analysis system.

The sequences were compared to the 16S rRNA gene sequences in the EMBL database (EMBL Outstation, Cambridge, United Kingdom), DSMZ database, and those of the Ribosomal Database Project (22).

Analytical procedures.

Bacterial growth was monitored routinely by recording the optical density at 550 nm, and the total cell count was determined by counting under the microscope by using a Thoma chamber.

Substrate concentrations of the odorous compounds were measured by headspace gas chromatography (GC) analysis. One milliliter of the culture medium was transferred into a 5-ml sample vial sealed with butyl rubber septa and an aluminum crimp seal and incubated in the incubator at 90°C for 1 h. Next, 500 μl of the gas phase was taken with a headspace sampler (HS MOD.250, Carlo Erba Instruments) and injected into the GC instrument (model GC 6000 Vega series 2; Carlo Erba Instruments, Milan, Italy) equipped with a flame ionization detector and fused silica capillary column DB-624 (30 m by 0.32 mm [inner diameter], 1.80-μm film thickness; J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA). The oven, injection port, and detector temperatures were 185, 200, and 250°C, respectively. Nitrogen was used as a carrier gas, with a flow rate of 20 ml min−1.

UV-visible absorption spectra were recorded with an Uvikon 930 spectrophotometer (Kontron Instruments, Le-Mont-sur-Lausanne, Switzerland). Pyrazines and their metabolites were identified by their characteristic UV absorption spectra between 200 and 400 nm.

For isolation and identification of DM metabolites, metabolites were isolated either from growing cultures of strain DM-11 in NF-M1 medium with DM (0.5 mM) as a sole source of carbon, nitrogen, and energy or by the preparative bioconversion of DM with freshly prepared resting cells of DM-11. The first type of preparation was based on the previous time course experiments in which metabolite formation was detected by UV-visible absorption spectra analysis of culture fluids. Cultures were incubated for 4 days at 25°C and 120 rpm. Then the cultures were centrifuged (8,600 × g, 4°C, 20 min) to remove cells. For the second type of preparation with resting cells, the transformation of DM (0.5 mM) was stopped when the conversion of the educts was complete. The cells were removed by centrifugation. In both preparations, the supernatants were extracted three times with 1 volume of dichloromethane. Extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. For the initial detection and characterization of metabolites, aliquots of the extracts were resuspended in dichloromethane and UV-visible absorption spectra were recorded. Portions of the extracts were further analyzed by GC-mass spectrometry (MS), i.e., the GC 8000 series coupled with an MD800 mass spectrophotometer (Fisons Instruments). Compounds were separated on a DB-5 MS fused silica capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm [inner diameter], 0.25-μm film thickness; J&W Scientific). The column temperature was kept at 60°C for 5 min, increased to 300°C at a rate of 5°C min−1, and then kept at 300°C for 20 min. Injector and analyzer temperatures were set at 290 and 315°C, respectively. The carrier gas was helium. The mass spectrometer was operated at 70 eV of electron ionization energy. Compounds not previously described in the literature were analyzed by 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). NMR spectra of the synthesized metabolite were obtained in chloroform-d1 recorded on a Bruker AMX 400 spectrophotometer (400 MHz for protons and 101 MHz for 13C spectra). Tetramethylsilane (δ = 0.00) was used as a calibration reference.

The metabolite, DHM, was synthesized according to the method described by Ohta et al. (23). 2,3-Diethyl-5-methylpyrazine was oxidized to the corresponding N-oxide with H2O2. The reaction with POCl3 yielded 2-chloro-5,6-diethyl-5-methylpyrazine. After reaction with solid NaOH at 180°C, DHM was obtained.

Ammonium (NH4+) was analyzed using an ammonium test kit (Spectroquant; Merck, Germany) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Mycobacterium strain DM-11 was deposited at the culture collection of the Institute of Technical Biocatalysis, Technical University Hamburg-Harburg, Hamburg, Germany. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain DM-11 was deposited at EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ nucleotide sequence databases under accession number AM113987.

RESULTS

Isolation and identification of DM-degrading strain DM-11.

A DM-degrading bacterium, strain DM-11, was isolated from a liquid sample from a waste gas treatment plant of the fishmeal processing industry in Germany. The strain formed rough white colonies on mineral M1 agar plates supplied with saturated vapor of DM as a sole carbon source. The scanning electron microscopy analysis of strain DM-11 showed that the bacterial cells were small rods 1.0 to 1.2 μm in length and 0.3 μm in diameter. The strain did not grow on complex media such as tryptic soy broth, nutrient broth, or Luria-Bertani medium or on simple carbon sources like glucose, acetate, succinate, oxoglutarate, or citric acid. Only on LJ medium was growth observed. Therefore, it was not possible to carry out the standard tests to identify this bacterium. 16S rRNA gene sequencing and taxonomic analysis revealed that this strain belongs to the genus Mycobacterium. However, as shown in Table 1, the similarity of the 16S rRNA gene sequence with the published 16S rRNA gene sequences of all previously described taxa of the genus Mycobacterium was rather low. The highest similarity was only 96.2% to the sequence of M. poriferae strain ATCC 35087T. This value is too low for species identification in this taxon (<99.5% similarity). Therefore, the strain DM-11 seems to be a new Mycobacterium species which has not been described before.

TABLE 1.

Comparison between the 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain DM-11 (AM113987) and those of closely related type strains of Mycobacterium species

| Species | Reference strain useda | Sequence database accession no.b | 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to AM113987c (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. poriferae | ATCC 35087T | AF480589 | 96.2 |

| M. abscessus | ATCC 19977T | M29559 | 95.7 |

| M. mycogenium | ATCC 49650T | AF480586 | 95.7 |

| M. cookii | ATCC 49103T | X53896 | 95.7 |

| M. ratisbonense | AF055331 | 95.7 | |

| M. senegalense | ATCC 35796T | M29567 | 95.7 |

| M. farcinogenes | ATCC 35753T | AF055333 | 95.5 |

| M. branderi | ATCC 51789T | X82234 | 95.2 |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.

Sequence databases: EMBL, Ribosomal Data Project, and DSM.

16S rRNA sequence of strain DM-11 deposited in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ sequence database.

Growth of Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 on DM as a carbon and nitrogen source.

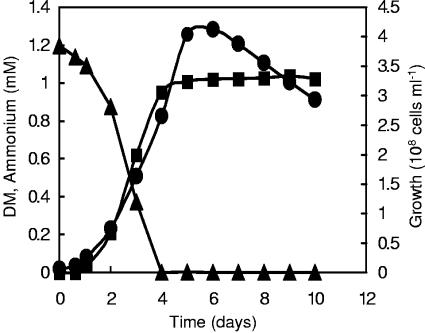

Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 was enriched, isolated, and routinely grown in mineral medium M1 containing 0.5 mM DM as a sole carbon and energy source. The strain grew optimally at 25°C and had a doubling time of 29.2 h with DM as substrate. In order to check whether strain DM-11 can also utilize DM as a sole source of nitrogen, growth of strain DM-11 in NF-M1 medium [mineral medium M1 without the addition of (NH4)2SO4] containing 1.2 mM DM as a sole carbon and nitrogen source was examined. During cultivation, DM was removed from the culture medium with corresponding increase in cell number (Fig. 1). After a lag phase of 1 day, the number of bacterial cells increased exponentially and reached stationary phase after 5 days of cultivation. The amount of ammonium in the culture medium increased gradually, parallel with the cells' growth, and reached the maximum of 0.95 mM after 4 days of cultivation. The accumulation of ammonium was not found in the control samples without DM-11 cells. The omission of (NH4)2SO4 from the mineral medium did not influence growth and final cell counts. The rate of DM degradation in the medium without (NH4)2SO4 was slightly higher than in the medium containing (NH4)2SO4. The final cell counts correlated with the amount of DM in the culture medium up to 5 mM. Further increase of DM concentration resulted in the inhibition of growth and DM degradation. These results show that strain DM-11 utilized DM as a sole carbon and nitrogen source without requiring other external carbon or inorganic nitrogen sources.

FIG. 1.

Time course of utilization of DM by Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 in liquid NF-M1 medium with 1.2 mM DM as the sole carbon and nitrogen source at 25°C and 120 rpm. Growth is shown as an increase in the cell numbers in cultures (circles). DM concentrations were determined by measuring absorbance at OD279 nm of the culture medium (triangles). Ammonium concentrations were measured using ammonium test method Spectroquant (squares). Data are means of results of duplicate experiments.

Metabolite formation during DM degradation.

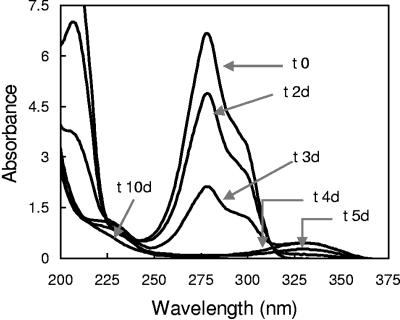

UV spectroscopy analyses of supernatants at different times from cultures of strain DM-11 in NF-M1 medium showed the transient accumulation of a metabolite. The changes in the UV spectrum during biodegradation of DM are illustrated in Fig. 2. DM had a maximum absorption at 279 nm. The amount of DM in the culture medium decreased rapidly and disappeared from the medium within 4 days of cultivation. As shown in Fig. 2, the accumulation of a metabolite, which had absorption maxima at 227 nm and 330 nm, was detected after 2 days of cultivation. The amount of the metabolite reached a maximum after 3 days; thereafter, the metabolite decreased and disappeared after 10 days. No other metabolite which had absorption spectra in the UV/visible spectrum (Vis) range was detected in the culture medium during the entire culture course (15 days). Controls without cells showed neither a decrease of DM nor formation of the metabolite or ammonium.

FIG. 2.

Changes in the UV spectrum during the cultivation of Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 in NF-M1 medium containing 1.2 mM DM as a sole carbon and nitrogen source at 25°C and 120 rpm. d, days.

Under anaerobic conditions, DM was not degraded by DM-11 and no metabolite was formed.

Isolation and identification of the metabolite.

For the isolation and identification of the metabolite, a large-scale conversion of DM was carried out using freshly prepared DM-grown resting cells of strain DM-11. The transformation of DM was stopped when the educt was no longer detectable with a spectrophotometer. To isolate the metabolite, the cell-free supernatant was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layer was concentrated and analyzed by coupled GC-MS. One new substance was detected. The molecular mass of the metabolite was found to be 16 atomic units higher than the molecular mass of DM. Therefore, the metabolite was regarded to be the product of an enzymatic oxidation of DM. This was in agreement with the results obtained by UV absorption spectra: the UV absorption maxima of the metabolite shifted to longer wavelengths, which suggested that the metabolite was a hydroxylated DM, as mentioned above. Also from the degradation of other N-heterocycles, we expected the structure of the metabolite obtained after the transformation of DM by strain DM-11 to be DHM. To prove this hypothesis, DHM was synthesized. The structure of the compound was confirmed by mass spectroscopy, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR analyses. The results obtained are shown in Table 2. The UV absorption spectrum of the synthesized DHM with absorption maxima at 227 nm and 330 nm was identical to the spectrum of the metabolite obtained during bioconversion of DM by DM-11. Furthermore, the mass spectra of the metabolite and the synthesized DHM were also identical, proving that the metabolite was indeed DHM.

TABLE 2.

Spectral data of the synthesized DHM

| Analysis type | Spectral data |

|---|---|

| Mass spectrum (EI, 70 eV) | 166 (M,53); 151 (13); 137 (19); 123 (100); 109 (9); 97 (15); 82 (60); 42 (44) |

| 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) | δ = 1.10-1.18 (m, 6H, 2*CH3); 2.28 (s, 3H, CH3); 2.46-2.54 (m, 4H, 2*CH2) |

| 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) | δ = 14.14 (CH3); 14.79 (CH3); 20.10 (CH3); 23.56 (CH2); 25.61 (CH2); 134.50 (C aromatic); 135.05 (C aromatic); 153.79 (C aromatic); 158.33 (C aromatic) |

Degradation of DHM by Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11.

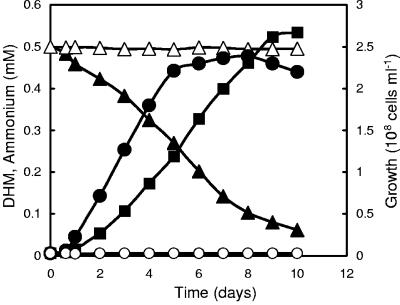

Cultivations of DM-11 in NF-M1 medium containing 0.5 mM DHM as the sole carbon and nitrogen source under aerobic and anaerobic conditions were investigated. As shown in Fig. 3, DM-11 did not grow on DHM under anaerobic conditions. Under aerobic conditions, DHM was steadily utilized and 90% of DHM disappeared from the culture medium after 10 days of cultivation. Exponential growth with a doubling time of 36.3 h was observed after a lag phase of 1 day, and after 5 days of cultivation, a stationary phase was reached. During degradation of DHM, ammonium was released into the medium. The rate of the ammonium accumulation was similar to the rate of DHM degradation. After 5 days, about 50% of the substrate was consumed. Although the decrease of the substrate and the production of ammonium continued beyond this point, the bacteria did not grow further. During cultivation, no other compound that had absorption spectra in the UV/Vis range was detected in the culture medium.

FIG. 3.

Effects of aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions on the biotransformation of DHM by Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11. Shown are levels of growth (circles), DHM degradation (triangles), and ammonium accumulation (squares) under aerobic conditions. Open circles and triangles show the levels of growth and DHM biotransformation under anaerobic conditions. Data are means of results from duplicate experiments.

Regulation of DM- and DHM-degrading enzymes in cells of Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11.

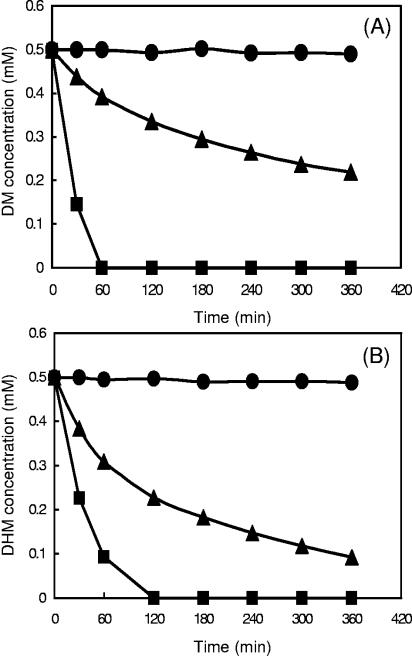

As shown in Fig. 4 A, DM-induced resting cells transformed DM quickly (8.33 μM min−1), and within 60 min, 0.5 mM DM disappeared from the suspension. DHM-induced resting cells also transformed DM immediately, however, at a lower rate. The initial rate of DM transformation by the DHM-induced resting cells was only 1.8 μM min−1, and 56.2% of DM disappeared from the cell suspension after 360 min of incubation. With noninduced resting cells, no decrease of DM was observed during the entire 360 min. It is noteworthy that the rate of DM transformation by DHM-induced resting cells without chloramphenicol was about two times higher than with the addition of chloramphenicol. The presence of chloramphenicol did not influence the DM transformation rate by DM-induced resting cells.

FIG. 4.

Conversion of DM (A) and DHM (B) by noninduced and induced resting cells of Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 under aerobic conditions. Resting cells were obtained by growth in NF-M1 medium with DM (0.5 mM) as DM-induced cells (squares) and with DHM (0.5 mM) as DHM-induced cells (triangles) or growth on LJ medium as noninduced cells (circles). The optical density at 550 nm of the resting-cell suspensions was 15. The DM and DHM concentrations in the resting-cell assays were monitored by UV absorption analysis at OD279 nm and OD330 nm, respectively. All experiments were done in the presence of chloramphenicol (100 μg ml−1). Data are means of results from duplicate experiments.

Biotransformation of DHM by DM (0.5 mM)-induced, DHM (0.5 mM)-induced and noninduced resting cells of DM-11 was also investigated. As shown in Fig. 4B, the rate of transformation of DHM by DM-induced resting cells (6.78 μM min−1) was about two times faster than that by DHM-induced cells (3.18 μM min−1). While DHM (0.5 mM) completely disappeared in the cell suspensions of DM-induced cells within 120 min, only 81.6% of DHM was degraded by DHM-induced cells after 360 min. In the presence of chloramphenicol, the noninduced resting cells did not transform DHM. The addition of chloramphenicol had no effect on the rate of DHM degradation by both DM- and DHM-induced resting cells.

Growth of Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 with other pyrazines, biotransformation by resting cells, and cometabolism by cells grown on DM.

A total of 13 pyrazines, which are frequently found in the waste gas from various food industries, were tested as substrates for growth, as substrates in biotransformations by resting cells of strain DM-11, and in cometabolism tests with the cells growing on DM. The UV spectrum after complete consumption of DM indicated whether the tested compound had been converted cometabolically. Either it was identical with the spectrum of the tested compound, indicating no cometabolic conversion, or it had been changed by the action of the cells, indicating cometabolic conversion. In some cases, the tested compound was consumed as a second growth substrate and completely degraded, which resulted in complete disappearance of the UV absorption. The third possibility was that the test compound inhibited the growth on DM. Then a mixed spectrum was obtained, which did not change during incubation. The results obtained are shown in Table 3. It was found that besides DM, strain DM-11 could utilize EMP and TMP as a sole carbon and nitrogen source for growth. The rate of TMP degradation in the cometabolic culture with DM was about two times faster than in the culture containing only TMP. No influence of DM on the rate of EMP degradation by strain DM-11 was observed. Conversion of AP, DEP, 2,3-DMP, 2,5-DMP, 2,6-DMP, EP, IP, and MP was possible only with resting cells of DM-induced cells of strain DM-11 or in cometabolic degradation during growth with DM. For DEP and IP, no cometabolic degradation was observed. IP inhibited DM degradation by DM-11 in the cometabolism experiment. P and TTMP were not transformed by strain DM-11.

TABLE 3.

Degradation of pyrazine compounds by Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 as a sole carbon and nitrogen source for growth, by resting cells (induced with DM), and by cometabolic conversion during growth with DM as the substratea

| Compoundb | Growth (day−1)c | Degradation (mM day−1)d | Transformation with resting cells (μM min−1)e | Cometabolic conversion during growth with DM (mM day−1)f |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | — | — | 0.2 | 0.03 |

| DM | 0.57 | 0.44 | 11.8 | 0.44 |

| DEP | — | — | 0.2 | — |

| 2,3-DMP | — | — | 0.4 | 0.01 |

| 2,5-DMP | — | — | 2.3 | 0.12 |

| 2,6-DMP | — | — | 0.5 | 0.07 |

| EMP | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 0.04 |

| EP | — | — | 0.4 | 0.01 |

| IP | — | — | 0.2 | —g |

| MP | — | — | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| P | — | — | — | — |

| TMP | 0.11 | 0.12 | 2.1 | 0.25 |

| TTMP | — | — | — | — |

Data are means from duplicate experiments. —, no activity or growth.

All the compounds were used at a final concentration of 0.5 mM.

Cultivations were carried out for 10 days. Cell growth and the concentration of the substrates in the culture medium were determined every day. The maximal growth rate during exponential growth is given.

The rate of compound degradation was determined during cultivation of strain DM-11 in NF-M1 medium containing the compound as a sole substrate.

Resting-cell experiments were carried out for 48 h. The concentrations of the substrates in the cell suspensions were determined every 30 min up to 4 h.

Cultivations were carried out for 10 days. The concentration of the substrates in the culture medium was determined every day.

Inhibited DM degradation.

DISCUSSION

In this work, a DM-degrading bacterium, strain DM-11, was isolated. It formed rough white colonies on mineral medium supplemented with saturated DM vapor as a sole carbon source. Cells were small rods, and the taxonomic properties were consistent with classification in the genus Mycobacterium. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain DM-11 showed highest similarity to Mycobacterium poriferae strain ATCC 35087T with a value of 96.2%. This value is far below the 99.5% that is usually found at the intraspecies level. This value is in the range that separates species at the intrageneric level (16). Combined genotypic and phenotypic data suggest that strain DM-11 merits recognition as a novel species within the genus Mycobacterium; we tentatively named the strain Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11.

Strain DM-11 could grow on DM without requiring any additional nitrogen, carbon or energy source. The ability to utilize N-heterocycles as a sole carbon, nitrogen, and energy source has been also reported for some other bacteria like Pseudomonas putida strain 01G3, which uses pyrrolidine and piperidine as the sole substrate for growth (33). To our knowledge, strain DM-11 is the first bacterium which is able to grow with 2,3-diethyl-5-methylpyrazine as the sole source of carbon, nitrogen, and energy.

During aerobic cultivation of strain DM-11, the amount of DM in the culture medium decreased concomitantly with the increase of a metabolite, identified as DHM. The metabolite DHM disappeared from the medium, and ammonium was released into the medium. The transient accumulation of DHM in the culture medium indicated that DHM was an intermediate in the degradation of DM and not a dead-end product. Therefore, DHM must be formed faster than it is degraded. This suggestion was supported by results shown in Fig. 2 and 3; the degradation of DM was faster than the degradation of DHM.

Experiments with noninduced (LJ-grown), DM-induced (DM-grown), and DHM-induced (DHM-grown) cells revealed that under conditions where de novo protein synthesis is inhibited, DM and DHM were transformed only when the enzymes for degradation had been induced by DM or DHM (Fig. 4). These findings suggest that the enzymes for DM and DHM degradation are inducible. It is noteworthy that the synthesis of the first enzyme, which catalyzes the transformation of DM to DHM, is also induced by DHM. Recently, the induction of enzymes by a metabolite formed during the degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons in Mycobacterium sp. has been reported (18).

Compared to DHM-induced cells, DM-induced cells exhibited high transformation rates for both DM and DHM (Fig. 4). Therefore, DM seems to be the better inducer for the enzymes.

DM degradation was complete after 4 days. During this degradation, about 4% was released as metabolite. When all DM was degraded, the cells continued to grow for another day. During this time, most of the metabolite was consumed. Then growth ceased, but the remaining metabolite was further degraded until no metabolite was left after 10 days without additional growth. We assume that after day 5, the concentration of the remaining metabolite was too low to sustain growth, and the metabolite was used in the maintenance metabolism of grown cells. When all metabolite was consumed, the cell number decreased. When cells were grown with DHM as the sole carbon source, growth stopped when about 50% of the substrate was consumed. At the moment, we have no simple explanation for this phenomenon. Since we know from the resting-cell experiments that DHM induces the first enzyme that converts DM to DHM to a lesser extent than the enzyme converting DHM, it could be that DHM is also a weak inducer for the lower degradation pathway. This could lead to the accumulation of toxic intermediates, which stop growth. Another theoretical explanation is the parallel induction of an alternative nonproductive degradation pathway, leading to products that inhibit growth. A final explanation can be given only when the complete pathway and its intermediates are known.

Since there was no nitrogen source in the culture medium except DM, the presence of ammonium in the culture broth indicates that the aromatic ring was cleaved and the nitrogen was released. The DM molecule has a low C/N ratio. Therefore, when all the carbon was used as the C and energy source, the excess N was released as ammonium. This explains why the addition of (NH4)2SO4 (2 g liter−1) to the culture medium did not affect growth or final cell numbers of DM-11. In NF-M1 medium, about 40% of the nitrogen from the pyrazine ring was detected as ammonium in the culture supernatant after complete degradation of DM. The accumulation of ammonium in the culture medium during growth of bacteria on heterocyclic compounds is not new. Ammonium accumulation was reported during cultivation of Rhodococcus erythropolis in a culture medium containing benzothiazoles as sole substrate (6). Mycobacterium sp. strain HE5 released ammonia into the medium during growth on morpholine (28). Cain and Watson (5) reported that ammonium accumulated during the biotransformation of pyridine by Nocardia sp. strain Z1. They also stated that the appearance of ammonium in the culture medium indicates the breakdown of the N-heterocycle (5, 6). In general, the metabolism of N-heterocycles is initiated by a ring hydroxylation adjacent to the N-heteroatom, followed by ring cleavage (6, 7, 13). Mattey and Harle (21) proposed that the metabolism of hydroxypyrazine by Pseudomonas sp. follows the general pattern of oxidation of aromatic rings by Pseudomonas species. The first step is probably dihydroxylation to 2,6-dihydroxypyrazine, followed by ring cleavage by an oxygenase (21). In most cases, the hydroxylation also occurred under anaerobic conditions and the hydroxyl group originated from water and not from molecular oxygen (7, 13, 31, 34). The regioselective monohydroxylations of pyrazine carboxylic acids at position C3 (the carbon atom between the ring, nitrogen and the carbon atom carrying the carboxyl group) to form 3-hydroxypyrazine-2-carboxylic acid, 3-hydroxy-5-methylpyrazine-2-carboxylic acid, and 3-hydroxy-5-chloropyrazine-2-carboxylic acid by cells of Ralstonia/Burkholderia sp. strain DSM 6920 grown with 6-methylnicotinate have been reported (32). These reactions were catalyzed by 6-methylnicotinate-2-oxidoreductase, which introduced a hydroxyl group containing oxygen derived from water and not from molecular oxygen (31, 32). Strain DSM 6920 did not utilize the hydroxylated products as growth substrates (32). The hydroxylation of pyrazine-2,3-dicarboxylic acid to 5-hydroxypyrazine-2,3-dicarboxylic acid by whole cells of Alcaligenes sp. strain UK21 has been reported. This reaction was found to be catalyzed by quinolinate dehydrogenase, which catalyzed the hydroxylation without molecular oxygen, and the hydroxy group was derived from water (34). In contrast to the above findings, DM was not degraded under anaerobic conditions, indicating that the transformation of DM into DHM requires molecular oxygen. The hydroxylation of heterocyclic compounds by oxidases found in mammals and rats (in most cases, by xanthine oxidase) is well established (1, 12, 30, 37, 40). The formation of 2-hydroxymorpholine by cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase was suggested as the initial step in morpholine degradation by Mycobacterium strain RP1 (24). Therefore, it is of interest to check which type of enzyme is responsible in DM-11 for the initial reaction in DM degradation. Purification and characterization of this enzyme are in progress in our laboratory.

The conversion of the first intermediate of the pathway, DHM, was accompanied by a complete disappearance of the UV absorption spectrum of this compound, and no other UV-absorbing intermediates were found. These findings and the liberation of ammonium during conversion of DM and DHM provide strong evidence that ring fission occurs after the formation of DHM, and ammonium was eliminated after ring cleavage.

Another possibility, based on the classical catalytic mechanism for ring cleavage of many heterocyclic compounds by bacteria, is the oxidation of the methyl group, followed by oxidative decarboxylation of the carboxyl group. Then ring fission between the hydroxylated carbon atoms could follow. However, we did not detect any intermediate of DHM that absorbed the UV light before ring cleavage. Therefore, this hypothesis is not very likely for the biodegradation of DHM. It is more likely that the aromatic ring of DHM is cleaved directly without oxidation at the methyl group. The involvement of bacterial dioxygenases in ring cleaving of N-heterocycles has been intensively reviewed by Fetzner (8). The observation that molecular oxygen is necessary for ring fission after DHM transformation indicates the involvement of oxygen in this reaction. The mechanisms of ring opening and the further catabolism of DHM are unknown and warrant further investigation. From the results obtained so far, an initial pathway for the microbial metabolism of DM by pure cultures of Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 is proposed in Fig. 5.

FIG. 5.

Suggested initial degradation of DM by Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11.

To see whether strain DM-11 would be a good candidate for waste gas purification, it was important to determine its ability to convert other related compounds often found in exhaust gases of food industries (Table 3). In addition to DM, strain DM-11 also utilized EMP and TMP as a sole substrate for growth. In the presence of DM, the degradation of TMP was faster. Although most of the pyrazines tested could not support the growth of DM-11 when supplied as a carbon and energy source, they were transformed by DM-grown resting cells and during growth with DM. Therefore, it is obvious that these compounds can be degraded by the same enzymes responsible for DM degradation by strain DM-11 but they may not act as inducers for the expression of these enzymes. Interestingly, we found that under all the conditions tested, DM-11 could not transform unsubstituted pyrazine and 2,3,5,6-tetramethylpyrazine.

This is the first time that the utilization of DM, as a sole substrate for growth, by a pure microbial strain has been described. The results presented here demonstrate that the new Mycobacterium sp. strain DM-11 has a promising potential for future use in the bioremediation of air polluted with substituted pyrazines.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) is gratefully acknowledged.

The work presented here is part of the project “Innovative methods for the collection and reduction of odor pollution from agriculture and food industry.” Information on this project is available at http://www.odour.de.

We thank C. Spröer (DSMZ) for providing information on the 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain DM-11 and its taxonomic analysis.

Footnotes

We dedicate this work to F. Lingens on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, T. B., J. Doull, V. J. Feron, J. I. Goodman, L. J. Marnett, I. C. Munro, P. M. Newberne, P. S. Portoghese, R. L. Smith, W. J. Waddell, and B. M. Wagner. 2002. The FEMA GRAS assessment of pyrazine derivatives used as flavor ingredients. Food Chem. Toxicol. 40:429-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, R., J. Saunders, and L. J. Street. 1989. Pyrazines, pyrimidines and pyridazines useful in the treatment of senile dementia. European Patent application 0327155.

- 3.Beck, H. C., A. M. Hansen, and F. R. Lauritsen. 2003. Novel pyrazine metabolites found in polymyxin biosynthesis by Paenibacillus polymyxa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 220:67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, D. J. 2002. The pyrazines supplement I. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 5.Cain, R. B., and G. K. Watson. 1975. Microbial metabolism of the pyridine ring: metabolic pathways of pyridine biodegradation by soil bacteria. Biochem. J. 146:157-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Wever, H., K. Vereecken, A. Stolz, and H. Verachtert. 1998. Initial transformations in the biodegradation of benzothiazoles by Rhodococus isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3270-3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fetzner, S. 1998. Bacterial degradation of pyridine, indole, quinoline, and their derivatives under different redox conditions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 49:237-250. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fetzner, S. 2002. Oxygenases without requirement for cofactors or metal ions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60:243-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grosch, W. 1993. Detection of potent odorants in foods by aromaextract dilution analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 4:68-73. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosch, W. 1994. Determination of potent dorants in food by aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA) and calculation of odour activity values (OAVs). Flavour Fragr. J. 9:147-158. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grosch, W. 2001. Evaluation of the key odorants of foods by dilution experiments aroma models and omission. Chem. Senses 26:255-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawksworth, G., and R. R. Scheline. 1975. Metabolism in the rat of some pyrazine derivatives having flavour importance in foods. Xenobiotica 5:389-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser, J. P., Y. Feng, and J. M. Bollag. 1996. Microbial metabolism of pyridine, quinoline, acridine, and their derivatives under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Microbiol. Rev. 60:483-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiener, A. 1992. Enzymatic oxidation of methyl groups on aromatic heterocycles: a versatile method for the preparation of heteroaromatic carboxylic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 31:774-775. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiener, A., J. P. Roduit, A. Tschech, A. Tinschert, and K. Heinzmann. 1994. Regiospecific enzymatic hydroxylations of pyrazinecarboxylic acid and practical synthesis of 5-chloropyrazine-2-carboxylic acid. Synlett 10:814-816. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, K. K., C. S. Lee, R. M. Kroppenstedt, E. Stackebrandt, and S. T. Lee. 2003. Gordonia sihwensis sp. nov., a novel nitrate-reducing bacterium isolated from a wastewater-treatment bioreactor. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 53:1427-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, N. D., M. K. Kwak, and S. G. Kim. 1997. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 2E1 expression by 2-(allylthio) pyrazine, a potential chemoprotective agent: hepatoprotective effects. Biochem. Pharmacol. 53:261-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krivobok, S., S. Kuony, C. Meyer, M. Louwagie, J. C. Willison, and Y. Jouanneau. 2003. Identification of pyrene-induced protein in Mycobacterium sp. strain 6PY1: evidence for two ring-hydroxylation dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 185:3828-3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maarse, H. 1991. Volatile compounds in food and beverages. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 20.MacDonald, J. C. 1973. Toxicity, analyses, and production of aspergillic acid and its analogues. Can. J. Biochem. 51:1311-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattey, M., and E. M. Harle. 1976. Aerobic metabolism of pyrazine compounds by a Pseudomonas species. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 4:492-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maidak, B. L., J. R. Cole, C. T. Parker, Jr., G. M. Garrity, N. Larsen, B. Li, T. G. Lilburn, M. J. McCaughey, G. J. Olsen, R. Overveek, S. Pramanik, T. M. Schmidt, J. M. Tiedje, and C. R. Woese. 1999. A new version of the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project). Nucleic Acids Res. 27:171-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohta, A., Y. Akita, and M. Hara. 1979. Syntheses and reactions of some 2,5-disubstituted pyrazine monoxides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 27:2027-2041. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poupin, P., N. Truffaut, B. Combourieu, P. Besse, M. Sancelme, H. Veschambre, and A. M. Delort. 1998. Degradation of morpholine by an environmental Mycobacterium strain involves a cytochrome P-450. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:159-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rainey, F. A., N. Ward-Rainey, R. M. Kroppenstedt, and E. Stackenbrandt. 1996. The genus Nocardiopsis represents a phylogenetically coherent taxon and a distinct actinomycete lineage; proposal of Nocardiopsaceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:1088-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranau, R., and H. Steinhart. 2004. Bewertung und Quantifizierung von Leitsubstanzen aus der geruchstragenden Abluft von Lebensmittelbetrieben und der Ferkelaufzucht. Erfassung und Minimierung von Gerüchen, p. 147-165. In B. Niemeyer, A. Robers, and P. Thiesen (ed.), Messung und Minimierung von Gerüchen. Hamburger Berichte 23, Verlag Abfall aktuell, Stuttgart, Germany.

- 27.Rappert, S., and R. Müller. 2005. Odor compounds in waste gas emissions from agricultural operations and food industries. Waste Manag. 25:887-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schräder, T., G. Schuffenhauer, B. Sielaff, and J. R. Andreesen. 2000. High morpholine degradation rates and formation of cytochrome P450 during growth on different cyclic amines by newly isolated Mycobacterium sp. strain HE5. Microbiology 146:1091-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Street, L. J., R. Baker, T. Book, A. J. Reeve, J. Saunders, T. Willson, R. S. Marwood, S. Patel, and S. B. Freedman. 1992. Synthesis and muscarinic activity of quinuclidinyl- and (1-azanorbornyl) pyrazine derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 35:295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stubley, C., J. G. P. Stell, and D. W. Mathieson. 1979. The oxidation of azaheterocycles with mammalian liver aldehyde oxidase. Xenobiotica 9:475-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tinschert, A., A. Kiener, K. Heizmann, and A. Tschech. 1997. Isolation of new 6-methylnicotinic-acid-degrading bacteria, one of which catalyses the regioselective hydroxylation of nicotinic acid at position C2. Arch. Microbiol. 168:355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tinschert, A., A. Tschech, K., Heinzmann, and A. Kiener. 2000. Novel regioselective hydroxylations of pyridine carboxylic acids at position C2 and pyrazine carboxylic acids at position C3. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 53:185-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trigui, M., S. Pulvin, P. Poupin, and D. Thomas. 2003. Biodegradation of cyclic amines by a Pseudomonas strain involves an amine mono-oxygenase. Can. J. Microbiol. 49:181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchida, A., M. Ogawa, T. Yoshida, and T. Nagasawa. 2003. Quinolinate dehydrogenase and 6-hydroxyquinolinate decarboxylase involved in the conversion of quinolinic acid to 6-hydroxypicolinic acid by Alcaligenes sp. strain UK21. Arch. Microbiol. 180:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Scoy, R. E., and C. J. Wilkowske. 1992. Antituberculous agents. Mayo Clin. Proc. 67:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner, R., M. Czerny, J. Bielohradsky, and W. Grosch. 1999. Structure-odour-activity relationships of alkylpyrazines. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. A 208:308-316. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitehouse, L. W., B. A. Lodge, A. W. By, and B. H. Thomas. 1987. Metabolic disposition of pyrazinamide in the rat: identification of a novel in vivo metabolite common to both rat and human. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 8:307-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wieser, M., K. Heinzmann, and A. Kiener. 1997. Bioconversion of 2-cyanopyrazine to 5-hydroxypyrazine-2-carboxylic acid with Agrobacterium sp. DSM 6336. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 48:174-176. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woolfson, A., and M. Rothschild. 1990. Speculating about pyrazines. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 242:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto, T., Y. Moriwaki, S. Takahashi, T. Hada, and K. Higashino. 1987. In vitro conversion of pyrazinamide into 5-hydroxypyrazinamide and that of pyrazinoic acid into 5-hydroxypyrazinoic acid by xanthine oxidase from human liver. Biochem. Pharmacol. 36:3317-3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]