Abstract

Pandoraea apista is recovered with increasing frequency from the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) and may represent an emerging pathogen (I. M. Jorgensen et al., Pediatr. Pulmonol. 36:439-446, 2003). We identified two CF patients from our hospital whose sputum specimens were culture positive for P. apista over the course of several years. Repetitive-element-sequence PCR was employed to determine whether sequential isolates that were recovered from these patients represented a single clone and whether each patient had been chronically colonized with the same strain. Banding patterns generated with ERIC primers, REP primers, and BOX primers showed that individual patient isolates had a high degree of similarity (>97%) and were considered identical. However, only the banding patterns from the ERIC primers and BOX primers were able to show that the strains from patients I and II were unique (similarity indices of 79.8% and 70.0%, respectively). We concluded that all strains of P. apista from patient I were identical, as were all strains from patient II, establishing chronic colonization. Only two of the three methods employed indicate that the strains from the two patients are distinct. This implied that the organism was not transferred from one patient to the other, suggesting that the choice of methodology could generate misleading results when examining person-to-person transmission regarding this organism.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most frequently encountered fatal autosomal recessive disease in the Caucasian population. The disease results from mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene that is located on chromosome 7 and is characterized by decreased chloride transport (8). As a consequence of this faulty transport mechanism, copious amounts of viscous respiratory secretions, which are difficult to clear and provide a breeding ground for microorganisms, are produced. The disease has a progressive microbiological history that begins with the acquisition of Staphylococcus aureus early in life, followed by chronic colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and transient infection with other gram-negative organisms, such as Klebsiella spp. or Citrobacter spp. (8). These infections lead to pulmonary exacerbations, and lung function decreases with each exacerbation (5). Pulmonary dysfunction is responsible for the majority of fatalities and is a direct result of these chronic infections (5). The median age of survival has increased in recent years to 33 years of age as a result of better antimicrobial therapy, nutritional support, and lung transplantation. However, the environment is a never-ending source for microorganisms, and novel organisms are associated with pulmonary exacerbations on a regular basis. One of these novel organisms is Pandoraea apista.

Pandoraea apista, named for Pandora's box (the origin of disease) and the Greek word apistos, meaning disloyal or treacherous, is an environmental gram-negative rod that was first isolated and identified in the late 1990s (1). The organism is oxidase variable (about 64% are oxidase positive), non-lactose-fermenting, motile via a single polar flagellum, urea positive, indole negative, and positive for growth at 42°C on cetrimide and Burkholderia cepacia-selective media but negative for growth on acetamide (1, 6). This organism was first recognized as a nosocomial pathogen and was often isolated from patients requiring chronic ventilation. In recent years, it has been isolated with increased frequency from the respiratory secretions of CF patients. The microbiology laboratory commonly misidentifies this organism as either a Ralstonia species or a Burkholderia species, the two genera that are most closely related phylogenetically and phenotypically to Pandoraea spp. (1, 10). In the setting of CF, it is important to correctly identify this organism, since patients with infections due to certain Burkholderia species are placed under strict contact isolation, may have a very rapid decline in pulmonary function, and at many centers are deemed unsuitable for lung transplants. Pandoraea apista can be definitively differentiated from other organisms via 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis (2, 9).

A report in 2003 by Jorgensen et al. highlighted the pathogenicity of this organism in the setting of CF and elevated Pandoraea apista to the status of a possible emerging infection in the CF community, along with other gram-negative organisms, such as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Achromobacter xylosoxidans subsp. xylosoxidans (6). They described a series of six patients, all of whom developed chronic colonization with a single clone of Pandoraea apista. Four of these patients appeared to have decreased lung function as a direct result of colonization. It was determined that the index patient had exposed the other five patients during a winter camp that all of the patients had attended over the course of several years (6). Their investigation described the possible deleterious affects of P. apista acquisition and the colonization and the high transmissibility of this organism, thereby heightening the need for isolation procedures regarding patients who are colonized with this organism. However, it remains unknown whether this organism is a chronic colonizer like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, causes transient infection, such as those caused by Klebsiella and Enterobacter spp., or constitutes a more serious infection like those associated with Burkholderia cepacia, Burkholderia cenocepacia, and Burkholderia multivorans.

We have identified two patients in our Adult Cystic Fibrosis Program at Barnes-Jewish Hospital whose respiratory secretions have been culture positive for Pandoraea apista over the course of several years despite treatment. To better understand the colonization profile of this organism, we employed the molecular typing techniques of repetitive-element-sequence PCR to determine whether sequential isolates from the two patients represented a single clone and to determine whether each patient was chronically colonized with the same strain.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1.

Patient I is a 30-year-old female who was diagnosed with CF at 2 years of age. She is homozygous for the δ-F508 mutation and first acquired Pandoraea apista in November of 1999. At this time, she was chronically colonized with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This initial P. apista isolate was identified by Peter Vandamme's laboratory at the University of Gent in Belgium. After confirmation of the identity of the organism, the patient was placed on contact isolation procedures when in the clinic and during hospitalizations. The susceptibility profile of the organism was determined by using disk diffusion criteria for non-Enterobacteriaceae species and showed susceptibility to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and ceftriaxone. The organism was resistant to ampicillin, gentamicin, tobramycin, imipenem, cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, colistin, and aztreonam. P. apista was isolated from her respiratory specimens every 3 months from 2000 to 2003, establishing chronic colonization (as defined by isolation of the organism in six consecutive cultures [6]). By February 2004, her forced expiratory volume in 1 s was 22% of predicted and she was diagnosed with hypercapnic respiratory failure. Following this diagnosis, cultures of her respiratory specimens were positive for P. apista in March, April, and May of 2004. In July of 2004, she was admitted to the hospital for pulmonary exacerbation, and during the course of her hospital stay, a suitable donor was found for lung transplant. She underwent a bilateral lung transplant in mid-July 2004, and on the day of transplant, her bronchus grew P. apista. Her posttransplant cultures were negative for P. apista until early August, when a bronchial wash was positive. She developed a pleural effusion which was culture positive for P. apista and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. After a few months of therapy, her respiratory cultures grew normal upper respiratory flora and her most recent bronchial alveolar lavage in April of 2005 was positive for P. aeruginosa but negative for P. apista.

Case 2.

Patient II is a 36-year-old male who was diagnosed with CF at 2 months of age. He was chronically colonized with Pseudomonas aeruginosa at the time that he acquired Pandoraea apista in April of 2001. This initial isolate's identification was confirmed by John LiPuma's group, the CFF Burkholderia cepacia Research Laboratory, at the University of Michigan. Patient II was also placed under isolation procedures during clinic visits and hospitalizations. The susceptibility profile of the organism was determined by using disk diffusion criteria for non-Enterobacteriaceae and demonstrated susceptibility to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cefepime, ceftriaxone, and piperacillin-tazobactam. The organism was resistant to ampicillin, gentamicin, tobramycin, imipenem, amikacin, colistin, and aztreonam. Patient II was culture positive again in February of 2002 and in January, May, June, August, and September of 2003, establishing chronic colonization. In May of 2003, his forced expiratory volume in 1 s was 19% of predicted and he underwent a bilateral lung transplant in September of 2003. P. apista was isolated from his first posttransplant bronchial washing, yet subsequent cultures have remained negative for P. apista. He currently has normal lung function, and his most recent bronchial alveolar lavage grew normal upper respiratory flora.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

The isolates from patient I that were used in this molecular analysis were from November of 1999 (I-1, her initial isolate), September of 2000 (I-2), and September of 2002 (I-3). The isolates from patient II were from April of 2001 (II-1, his initial isolate), February of 2002 (II-2), May of 2003 (II-3), and September of 2004 (II-4, the isolate posttransplant). The identification of all seven isolates was confirmed as Pandoraea apista by John LiPuma's laboratory and were stored at −70°C for further testing. DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA Mini kits (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 ml of overnight growth was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min and resuspended in 180 μl of supplied ATL buffer. DNA was eluted to a final volume of 200 μl in supplied elution buffer and stored at 4°C for further testing.

Repetitive-element-sequence PCR. (i) ERIC-PCR and REP-PCR.

Repetitive-element-sequence PCR was performed as previously described (4). Briefly, ERIC (enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence) primers (forward, 5′-ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG-3′) were used at a concentration of 125 pmol/2.5 μl in a 25-μl reaction mixture volume. Approximately 50 ng of DNA was used per reaction. Master mix was prepared with ready-to-go RAPD analysis beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, NJ). The reactions were performed on the GeneAmp PCR system 9700, version 2.25 (PE Applied Biosystems). After an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 7 min, 30 cycles were performed of 90°C for 15 s, 51°C for 30 s, and 65°C for 7 min with a final extension at 65°C for 14 min. REP (repetitive extragenic palindromic consensus sequence) primers (forward, 5′-IIIICGICGICATCIGGC-3′, and reverse, 5′-IGCICTTATCIGGCCTAC-3′) were used in the same concentration as the ERIC primers, and the PCR protocol that was utilized was an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 90°C for 15 s, 40°C for 30 s, and 65°C for 7 min, with a final extension at 65°C for 14 min.

PCR products were electrophoresed at 100 V on a 1% agarose gel made with 40 mM Tris acetate-1 mM of EDTA buffer and 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml. Banding patterns were analyzed with Molecular Analyst software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). A relatedness cutoff of 85% was used to determine homology.

(ii) BOX-PCR.

DNA was extracted from each of the isolates as described above. BOX-PCR was performed according to the protocol of Coenye et al. (3). Briefly, a PCR volume of 25 μl contained 1 μl of the BOX-A1R primer (5′-CTACGGCAAGGCGACGCTGACG-3′), 2 μl of genomic DNA, 2 U of Taq polymerase, 1.25 μl of 25 mM of each triphosphate, 2.5 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.4 μl of bovine serum albumin, and 5 μl of 5× Gitschier buffer. The amplification cycle consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 3 s, 92°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min, and 65°C for 8 min, with a final extension time of 65°C for 8 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed at 60 mA for 4 h at room temperature on a 1.5% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide and analyzed with Molecular Analyst software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The similarity index (SI) of the cluster analysis was performed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages.

RESULTS

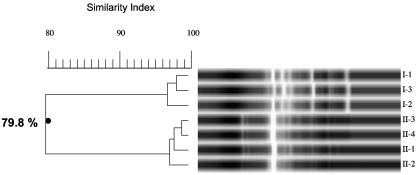

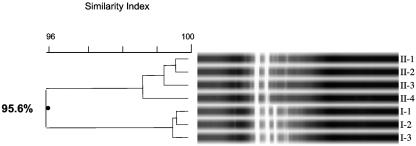

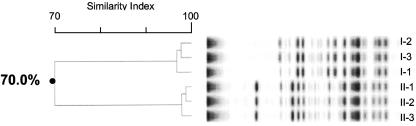

We employed repetitive-element-sequence PCR in an effort to determine chronic colonization with and person-to-person transmission of P. apista in our two cystic fibrosis patients. The DNA fingerprints of the seven isolates of Pandoraea apista that were generated with the ERIC primer set are shown in Fig. 1. The banding patterns indicate that isolates I-1, I-2, and I-3 form one cluster with an SI of >96%, and II-1, II-2, II-3, and II-4 form a second cluster with an SI of >96%. The overall banding pattern indicates that there are two distinct clusters with SIs of 79.8%. Figure 2 demonstrates the banding pattern that was achieved using the REP primer set. Analysis of these DNA fingerprints indicate that I-1, I-2, and I-3 form one cluster with an SI of >99%, and II-1, II-2, II-3, and II-4 form a second cluster with an SI of >98%. However, the overall banding pattern indicates that the two clusters are indistinguishable with overall SIs of 95.6%. Results obtained utilizing the BOX-PCR technique are shown in Fig. 3. I-1, I-2, and I-3 form a distinct cluster with an SI of >96%, and II-1, II-2, and II-3 form a second cluster with an SI of >96%. (Isolate II-4 was not included in this analysis.) The overall banding pattern is consistent with the ERIC-PCR results and demonstrates two unique clusters with SIs of 70%.

FIG. 1.

ERIC-PCR DNA fingerprint of seven Pandoraea apista isolates. Lanes labeled I-1, I-2, and I-3 are isolates from patient I. Lanes labeled II-1, II-2, II-3, and II-4 are isolates from patient II.

FIG. 2.

REP-PCR DNA fingerprint of seven Pandoraea apista isolates. Lanes labeled I-1, I-2, and I-3 are isolates from patient I. Lanes labeled II-1, II-2, II-3, and II-4 are isolates from patient II.

FIG. 3.

BOX-PCR DNA fingerprint of seven Pandoraea apista isolates. Lanes labeled I-1, I-2, and I-3 are isolates from patient I. Lanes labeled II-1, II-2, and II-3 are isolates from patient II. (Isolate II-4 from patient II was not included in this analysis.)

Collectively, the data indicate that all techniques agree that the three isolates that were tested from patient I are identical. All three techniques also agree that the four isolates that were tested from patient II are identical. Of note, the isolate that was cultured from the pleural fluid of patient I following transplant displayed an ERIC-PCR fingerprint that was identical to those of the three isolates examined here (data not shown). This analysis supports chronic colonization and corroborates the clinical diagnosis of chronic colonization in both patients. However, only the ERIC-PCR and BOX-PCR fingerprint analyses confirm that the isolates from the two patients are distinct and do not represent a single clone that was spread from one patient to the other.

DISCUSSION

The gold standard for epidemiological studies is pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), following restriction enzyme digestion of genomic DNA. Since PFGE is time-consuming and labor-intensive, effort has been put forth to design techniques that utilize PCR, as the results are determined in a timelier manner and elaborate equipment is not required. In the setting of cystic fibrosis, several PCR techniques have been optimized to identify and epidemiologically link gram-negative organisms. Coenye et al. reported that, with regard to Burkholderia cenocepacia (formerly Burkholderia cepacia genomovar III) epidemiology studies, the BOX-PCR demonstrates overall agreement with PFGE and may be superior to PFGE when trying to perform large-scale epidemiological investigations (3). Liu et al. demonstrated that, for the analysis of small numbers of Burkholderia cepacia isolates, ERIC-PCR was a viable and reliable alternative to PCR-ribotyping and arbitrarily primed PCR (7). Dunne and Maisch (4) successfully employed ERIC-PCR and REP-PCR in an epidemiological investigation of Alcaligenes species that were thought to be involved in an outbreak among children with CF, and most recently, Syrmis et al. (11) showed that both ERIC-PCR and BOX-PCR are reliable and highly discriminatory for surveillance studies regarding Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from CF patients.

The first reported epidemiological analysis of Pandoraea apista isolates was carried out by Jorgensen et al. by using PFGE following Xba and Dra digestions of genomic DNA (6). To our knowledge, there are no other reports documenting the use of molecular assays for epidemiological purposes regarding Pandoraea apista. We chose to use ERIC-PCR, REP-PCR, and BOX-PCR for a small-scale epidemiological evaluation of seven clinical isolates in order to determine whether a common source was responsible for the patients' colonization and to molecularly distinguish colonization from reinfection.

In our current study, all three systems agree that the isolates that were cultured from each patient are identical, indicating chronic colonization with a single clone rather than repeated infection. However, only ERIC-PCR and BOX-PCR were able to determine that the isolates cultured from each patient were unique and not acquired via exposure to a common environmental source or via person-to-person transmission. These data highlight that the use of a single molecular assay, in this case the REP-PCR, could lead to a misinterpretation of the outbreak being investigated. A disadvantage when analyzing Pandoraea apista with the REP-PCR method is the lack of bands that are produced with this primer set. There were not enough bands produced to allow for statistical separation of the P. apista isolates under examination. Therefore, the caution raised is that, when utilizing rapid molecular techniques in the setting of an epidemiological survey regarding a novel organism, it may be prudent to try several methods to find the one or two that give the most reproducible and reliable data for the given setting.

At this time, the impact of Pandoraea apista colonization in these patients remains ambiguous. Following recommendations for protecting the CF community, our two patients were placed under contact isolation procedures during clinic visits and hospitalizations (12). We have established chronic colonization, clinically and molecularly, and there was a documented decline in these individuals' lung function after acquisition, but it remains unclear whether this is a casual association or is a direct result of infection with P. apista. The P. apista colonization in these two patients appears to have been eradicated by the removal of a reservoir of infection in combination with aggressive and targeted antimicrobial therapy posttransplantation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coenye, T., E. Falsen, B. Hoste, M. Ohlen, J. Grois, J. R. W. Govan, M. Gills, and P. Vandamme. 2000. Description of Pandoraea gen. nov. with Pandoraea apista sp. nov., Pandoraea pulmonicola sp. nov., Pandoraea pnomenusa sp. nov., Pandoraea sputorum sp. nov., and Pandoraea norimbergensis comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:887-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coenye, T., L. Liu, P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2001. Identification of Pandoraea species by 16S ribosomal DNA-based PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4452-4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coenye, T., T. Spilker, A. Martin, and J. J. LiPuma. 2002. Comparative assessment of genotyping methods for epidemiologic study of Burkholderia cepacia genomovar III. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3300-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunne, W. M., and S. Maisch. 1995. Epidemiological investigation of infections due to Alcaligenes species in children and patients with cystic fibrosis: use of repetitive-element-sequence polymerase chain reaction. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:836-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilligan, P. 1991. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:35-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jorgensen, I. M., H. K. Johansen, B. Frederiksen, T. Pressler, A. Hansen, P. Vandamme, N. Holby, and C. Koch. 2003. Epidemic spread of Pandoraea apista, a new pathogen causing severe lung disease in cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 36:439-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu, P. Y. F., Z. Y. Shi, Y. J. Lau, B. S. Hu, J. M. Shyr, W. S. Tsai, Y. H. Lin, and C. Y. Tseng. 1995. Comparison of different PCR approaches for characterization of Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:3304-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renders, N., H. Verbrugh, and A. Van Belkum. 2001. Dynamics of bacterial colonization in the respiratory tract of patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 1:29-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segonds, C., S. Paute, and G. Chabanon. 2003. Use of amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis for identification of Ralstonia and Pandoraea species: interest in determination of the respiratory bacterial flora in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3415-3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stryjewski, M. E., J. J. LiPuma, R. H. Messier, L. B. Reller, and B. D. Alexander. 2003. Sepsis, multiple organ failure, and death due to Pandoraea pnomenusa infection after lung transplantation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2255-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syrmis, M. W., M. R. O'Carroll, T. P. Sloots, C. Coulter, C. E. Wainwright, S. C. Bell, and M. D. Nissen. 2004. Rapid genotyping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates harboured by adult and paediatric patients with cystic fibrosis using repetitive-element-based PCR assays. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:1089-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vonberg, R. P., and P. Gastmeier. 2005. Isolation of infectious cystic fibrosis patients: results of a systematic review. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 26:401-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]