Abstract

The pH strongly influenced the development of colonies by members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria on solid laboratory media. Significantly more colonies of this group formed at pH 5.5 than at pH 7.0. At pH 5.5, 7 to 8% of colonies that formed on plates that were incubated for 4 months were formed by subdivision 1 acidobacteria. These colonies were formed by bacteria that spanned almost the entire phylogenetic breadth of the subdivision, and there was considerable congruence between the diversity of this group as determined by the cultivation-based method and by surveying 16S rRNA genes in the same soil. Members of subdivision 1 acidobacteria therefore appear to be readily culturable. An analysis of published libraries of 16S rRNAs or 16S rRNA genes showed a very strong correlation between the abundance of subdivision 1 acidobacteria in soil bacterial communities and the soil pH. Subdivision 1 acidobacteria were most abundant in libraries from soils with pHs of <6, but rare or absent in libraries from soils with pHs of >6.5. This, together with the selective cultivation of members of the group on lower-pH media, indicates that growth of many members of subdivision 1 acidobacteria is favored by slightly to moderately acidic growth conditions.

Members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria (29) are widely distributed in soils and other habitats (2, 3, 5, 17, 19, 28, 29, 31, 34, 43, 45) and have been shown to be present as active cells (13, 17, 29, 30). This subdivision should be regarded as a class-rank taxon (21). Kishimoto and Tano (23) cultured eight isolates from water, mud, and soil that were affected by acid mine runoff, one of which was subsequently described as Acidobacterium capsulatum (2). To date, this is still the only validly described species in this subdivision.

Since the description of A. capsulatum, one isolate from the sediment of an acid mine drainage treatment system (18), four isolates from a soil in Michigan (42), and 48 isolates from a soil in Victoria, Australia (8, 20, 21, 35) have been reported. Very little is known of the biology of this group (33), and no specific isolation methodologies have been developed to culture subdivision 1 acidobacteria. Detailed study of isolates that represent the phylogenetic breadth of the subdivision will allow a better understanding of their roles in soil.

Stevenson et al. (42) monitored the appearance of colonies of members of the phylum Acidobacteria by PCR and found that acidobacteria formed colonies on solid media incubated under air enriched with CO2, but not on parallel media incubated under air. The four acidobacterial isolates obtained in that study were all members of subdivision 1. It was not clear if the isolation of acidobacteria in these experiments was the result of the presence of CO2 or an associated drop in pH of the culture media due to the mildly acidic nature of dissolved CO2 (42). We have investigated the effects of CO2 and medium pH on the culturability of subdivision 1 acidobacteria and the phylogenetic diversity of isolates obtained.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil collection and sample preparation.

Soil cores were collected from a rotationally grazed perennial ryegrass (Lolium perene) and white clover (Trifolium repens) pasture (40) at the Dairy Research Institute, Ellinbank, Victoria, Australia (38°14.55′S, 145°56.11′E). A 25-mm-diameter metal corer was used to obtain 100-mm-long soil cores, which were transported intact at ambient temperature in sealed polyethylene bags and processed within 3 h of collection. The upper 30 mm of each core was discarded, and large roots and stones were removed from the remainder, which was then sieved through a sterile brass sieve with a 2-mm aperture size (Endecotts Ltd.) and used immediately for cultivation experiments or frozen at −20°C prior to DNA extraction.

Clone library preparation.

DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of soil using the methods described by O'Farrell and Janssen (32). The primer pair 31f (3) and 1492r (26), designed by Barns et al. (3) to amplify 16S rRNA genes from members of subdivisions 1 to 6 of the phylum Acidobacteria, was used to amplify 16S rRNA genes from this DNA. The PCR mixture contained PCR buffer (QIAGEN Pty. Ltd., Clifton Hill, Victoria, Australia), 1 μl of the template DNA, 1 or 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 pmol of each primer, 1.25 M betaine, and 6.25% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide in a total volume of 40 μl, and overlaid with 2 drops of mineral oil (Promega Corp., Annandale, New South Wales, Australia). After heating at 94°C for 2 min, 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (QIAGEN) and 10 nmol of each deoxyribonucleoside phosphate were added to each reaction in a volume of 10 μl.

Amplification occurred during 30 cycles consisting of annealing at 42°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 60 s, and denaturation at 94°C for 5 s. After 30 cycles, there was a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The products from two reactions containing 1 mM MgCl2 and from two reactions with 1.5 mM MgCl2 were pooled and then purified, A-tailed, and cloned in Escherichia coli as described elsewhere (32). The cloned 16S rRNA gene fragments were reamplified and screened after digestion with a restriction endonuclease (32) with HhaI (Promega) at 3 U of restriction endonuclease and 1 μg of DNA at 37°C for 3 h.

Cultivation.

We carried out plate count experiments with medium VL55 (39), which has a pH of 5.5, and medium VL70 (39), which has a pH of 7.0. These media are identical except for the pH buffer. The media were solidified with 0.8% (wt/vol) gellan (8) and supplemented with 0.05% (wt/vol) xylan, with 0.05% (wt/vol) carboxymethyl cellulose, with 2 mM N-acetylgluosamine, with 0.5 mM each of d-glucose, d-galactose, d-xylose, and l-arabinose, with an amino acid mixture (21), or with dilute nutrient broth, which was prepared by adding 0.08 g of Difco nutrient broth powder (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, Md.) per liter of medium.

Plate count experiments were prepared as described by Davis et al. (8). Six replicate sets of plates were set up for each experiment and treatment, and each set of plates consisted of three different inoculum levels, each with three replicate plates (8). The plates were incubated aerobically in sealed polyethylene bags (40-μm film thickness) at 25°C in the dark for 4 months. Some plates were incubated at 25°C under an air atmosphere enriched with 5% (vol/vol) CO2, in a model 3157 CO2 incubator (Forma Scientific, Marietta, Ohio) that had been calibrated at 25°C using a Fyrite CO2 analyzer (Bacharach, Pittsburgh, Pa.). Colonies were counted at monthly intervals by viewing the plates on a light box under a magnifying lens (up to 1.5× magnification).

To test the effects of CO2 on pH, 10-ml aliquots of uninoculated medium VL55, without gellan, were incubated under CO2enriched air. The effect of CO2 on the pH of the medium of Stevenson et al. (42) was tested in the same way.

Controls for hybridization.

Almost complete 16S rRNA genes in the pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega) that had been amplified by PCR from a sample of DNA extracted from soil from the Ellinbank sample site in an earlier study (L. Schoenborn and P. H. Janssen, unpublished data) or in this study were used as positive and negative controls to find appropriate hybridization conditions. These genes, the GenBank accession numbers of their sequences, and the phylogenetic affiliations of their hosts were EC1005 (DQ083243; phylum Acidobacteria, subdivision 1), EC1027 (DQ083258; phylum Acidobacteria, subdivision 1), EC1007 (DQ083245; phylum Acidobacteria, subdivision 3), EC1075 (DQ083285; phylum Acidobacteria, subdivision 3), EC1096 (DQ083299; phylum Acidobacteria, subdivision 4), EB1001 (AY395320; phylum Verrucomicrobia, class “Spartobacteria”), EB1002 (AY395321; phylum Gemmatimonadetes), EB1010 (AY395329; phylum Firmicutes, class Bacilli), EB1016 (AY395335; phylum Actinobacteria, subclass Actinobacteridae), EB1034 (AY395353; phylum Proteobacteria, class Alphaproteobacteria), EB1038 (AY395357; phylum Planctomycetes), EB1054 (AY395373; phylum Proteobacteria, class Gammaproteobacteria), EB1065 (AY395384; phylum Chloroflexi), EB1076 (AY395395; Proteobacteria, class Deltaproteobacteria), and EB1078 (AY395397; phylum Proteobacteria, class Betaproteobacteria).

In addition, plasmids containing almost complete 16S rRNA genes from Acidobacterium capsulatum strain 161 (D26171; phylum Acidobacteria, subdivision 1), Haloferax volcanii NCIMB 2012 (AY425724, Archaea), and the 18S rRNA gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATCC 9763 (Eucarya) were also used as controls. The oligonucleotide probe targeting subdivision 1 acidobacteria had perfect matches to sequences EC1005 and EC1027, each of which had one of the two variant probe targets conferred by the twofold degeneracy of the probe (see below). The 16S rRNA gene from A. capsulatum also had a perfect match to one of the probe variants.

Escherichia coli JM109 containing the pGEM T-Easy vector with the appropriate 16S rRNA gene insert was grown in Luria-Bertani broth (37) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. The cells were harvested from 30 ml of an overnight culture by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 20 min at room temperature, and the plasmid was extracted from the cell pellet using a Concert rapid plasmid miniprep kit (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, Md.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids were suspended in water, and the amount of DNA in each preparation was quantified by UV spectrophotometry (37).

Detection of acidobacteria.

Probe AC1-231 (5′-CTAATCRGCCGCGACCC-3′; R = equimolar G and A) was designed to be complementary to a region of the 16S rRNA genes of members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria. The probe AC1-231 and the EUB probe suite, consisting of an equimolar mixture of probes EUB338, EUB338II, and EUB338III (7), were purchased as high- performance liquid chromatography-purified oligonucleotides from GeneWorks (Thebarton, South Australia, Australia), and labeled with a single digoxigenin molecule at the 3′ terminus using the DIG Oligonucleotide 3′-end labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics Australia, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The EUB probe suite (7), which contains oligonucleotides that are complementary to a region of the 16S rRNA gene of nearly all members of the domain Bacteria, bound to the control 16S rRNA genes from bacteria except EB1038, but not to homologs from the archaeon Haloferax volcanii or from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae at a hybridization temperature of 55°C (data not shown). The three sequences to which the probes did not bind did not contain exact target regions for any of the probes in the EUB probe suite.

Almost complete 16S rRNA genes were amplified from colonies by PCR (35). Plasmids of hybridization controls (approximately 3 ng) or unpurified PCR products (1 μl) were applied to positively charged nylon membranes, and products hybridizing with the probe AC1-231 or with the EUB probe suite were identified using a digoxigenin-based detection system (38).

Gene sequence analysis.

The primary sequences of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes from the colonies or from cloned DNA fragments were determined as described by Sait et al. (35), and the phylogenetic affiliations of their source bacteria were deduced using BLAST in GenBank (1, 4). For more detailed phylogenetic analyses, 16S rRNA gene sequences were aligned against selected sequences extracted from GenBank, using the program ClustalX, version 1.81 (44). This alignment was then manually checked and corrected, and regions of uncertain alignment eliminated, using the software SeAl version 1.d1 (A. Rimbaut, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, United Kingdom).

Evolutionary analyses were carried out with the PHYLIP package, version 3.573c (J. Felsenstein, Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle) (12). Evolutionary distances between pairs of microorganisms were determined by the Jukes and Cantor (22) method and the maximum likelihood method implemented in the Dnadist program, and dendrograms were derived with the Fitch and Neighbor programs, employing the Fitch-Margoliash method (14) and a neighbor-joining algorithm (36), respectively. The significance of the nodes was tested by bootstrap analysis generating Jukes-Cantor evolutionary distances and using the least squares and neighbor-joining algorithms to produce 1,000 dendrograms, and then compiling consensus dendrograms, using the programs Seqboot, Dnadist, Fitch, Neighbor, and Consense. Maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony analyses of the sequence data employed the programs Dnaml and Dnapars, respectively. Dendrograms were represented graphically with the software TreeViewPPC version 1.4 (R. D. M. Page, Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom). The topologies and bootstrap values of dendrograms produced using different methods were not significantly different.

Uncorrected phylogenetic distances between 16S rRNA genes were calculated using ClustalX.

Statistical analyses.

Student's t test and the χ2 test were performed using Excel software (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Wash.). Data were fitted to an exponential function using Cricket Graph III (Computer Associates International, Inc., Islandia, N.Y.), and the significance of the correlation coefficient was tested as described by Sokal and Rohlf (41).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in the GenBank databases under accession numbers DQ075265 to DQ075314, DQ083241 to DQ083327, and DQ097336.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Survey of acidobacteria.

We wanted to use an oligonucleotide probe to detect colonies formed by members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria, but we were unable to design a probe that should bind specifically to 16S rRNA genes of all members of this group. To facilitate the development of a probe that would detect subdivision 1 acidobacteria in the soil being used in this study, a library of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes from members of the phylum Acidobacteria was prepared from DNA extracted from the Ellinbank pasture soil. A total of 130 clones were screened by digestion with the restriction endonuclease HhaI to resolve them into 63 different restriction pattern groups with a maximum of 10 and a mean of 2.1 clones per group. A set of 87 of these clones were partially or fully sequenced (GenBank accessions DQ083241 to DQ083327) to permit assignment of the different restriction fragment pattern groups to different subdivisions of the phylum Acidobacteria.

For restriction fragment pattern groups with more than one clone, at least two clones were sequenced. All sequenced clones belonging to the same restriction fragment pattern group belonged to the same subdivision. Five of the clones, representing two restriction fragment pattern groups, turned out to originate from members of the phylum Chloroflexi. The remaining 125 clones were assigned to five of the recognized subdivisions of the phylum Acidobacteria, as defined by Hugenholtz et al. (19), and to a new subdivision (Table 1). The primers used (3) do not amplify 16S rRNA genes from members of subdivision 7 or 8 of the Acidobacteria, and no members of these subdivisions were detected in the library. Members of subdivision 1 dominated the library, making up over half of the clones (Table 1), and we deduce that this group is the most abundant of those detected using these primers.

TABLE 1.

Affiliation of PCR-amplified and cloned 16S rRNA genes with different subdivisions of the phylum Acidobacteria

| Acidobacteria subdivisiona | No. of clones (%) | No. of restriction enzyme digestion patterns | No. of clones sequenced |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68 (54.4) | 30 | 42 |

| 3 | 28 (22.4) | 11 | 20 |

| 4 | 5 (4.0) | 5 | 5 |

| 5 | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 22 (17.6) | 13 | 17 |

| Unnamed | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 125 (100) | 61 | 86 |

Numbered subdivision designations are those of Hugenholtz et al. (19).

Development of a DNA probe.

We were able to identify a suitable probe target in the 16S rRNA genes of 35 of the 42 sequences (i.e., 83%) that were affiliated with subdivision 1 in the library we prepared from the soil we were investigating. These sequences represented 85% of the PCR-amplified, cloned 16S rRNA genes. The oligonucleotide probe AC1-231 was designed to bind to this target region. Six of the seven sequences without exact matches to the probe had only one difference. Exact matches to this probe were found in only 51 of 86 (i.e., 59%) of a selection of 16S rRNA gene sequences from subdivision 1 acidobacteria extracted from GenBank. Therefore, while the probe was not useful as a tool for detecting all subdivision 1 acidobacteria, it was useful as a site-specific tool to analyze the culturability of members of this group from our study site.

Of 103,323 16S rRNA gene sequences in the Ribosomal Database project (6) that contained the probe target region (25 May 2005), only seven sequences not listed as acidobacteria contained a perfect match to the probe. All seven were either chimeras derived from a member of subdivision 1 of the acidobacteria and another bacterium or were not correctly labeled as subdivision 1 acidobacteria. This suggests that the probe should be specific for subdivision 1 acidobacteria.

Using a range of 16S rRNA genes on plasmids as positive and negative controls, probe binding was found to be specific at a hybridization and wash temperature of 56°C. Under these conditions, the probe bound to the three control cloned 16S rRNA gene fragments (EC1005, EC1027, and A. capsulatum) derived from members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria, to which the probe has perfect matches, and to none of the negative controls listed in the Materials and Methods section.

Effect of pH and CO2.

Stevenson et al. (42) suggested that increased CO2 partial pressures or low pH may allow more successful isolation of at least members of subdivision 1 from soil. We tested this in a systematic study, using the oligonucleotide probe we designed to detect colony formation by members of this group. Two separate experiments were set up, each testing one of the factors we were interested in: the effect of CO2 and the effect of pH on the isolation of subdivision 1 acidobacteria. In experiment A, xylan-containing plates at pH 5.5 were incubated under air and under air with 5% (vol/vol) CO2. In experiment B, xylan-containing plates at pH 5.5 and pH 7.0 were incubated under air. Each experiment therefore replicated the plates at pH 5.5 incubated under air. This allowed us to estimate experiment-to-experiment variation and compare that to variable-associated differences.

The number of CFU able to form visible colonies after 4 months of incubation at 25°C (Table 2) was not significantly different by experiment or variable (Student's t test, P = 0.42 to 0.81 for the different comparisons). As found by Stevenson et al. (42), subtle changes in medium or incubation conditions did not measurably affect the overall culturability of soil bacteria, although it is possible that different subsets of the community grew under the different conditions. To assess this, we counted the number of colonies formed by members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria.

TABLE 2.

Cultivation of members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria under different incubation conditions

| Expt | Treatment | CFU of culturable microorganisms (SD) | No. of EUB suite-positive colonies | No. of AC1- 231-positive colonies | No. of confirmed subdivision 1 acidobacteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | pH 5.5, aira | 1.6 × 108 (2.8 × 107) | 218 | 17 | 16 (7.3)b |

| pH 5.5, air + CO2 | 1.5 × 108 (3.1 × 107) | 188 | 15 | 12 (6.4) | |

| B | pH 5.5, aira | 1.7 × 108 (5.7 × 107) | 165 | 13 | 13 (7.9) |

| pH 7.0, air | 1.5 × 108 (3.1 × 107) | 183 | 5 | 5 (2.7) | |

| All | All | 574 | 50 | 46 (6.1) |

These experiments are replicates under the same conditions.

Percentage of EUB suite-positive colonies.

After 4 months, visible colonies were randomly selected from plates on which a mean of 10.7 colonies (range, 1 to 44) had developed. Almost complete 16S rRNA genes were amplified from colonies by PCR, and the PCR products were screened to determine which had originated from members of subdivision 1 acidobacteria by using the oligonucleotide probe, AC1-231. Fifty of 574 (i.e., 8.7%) colonies yielded PCR products that bound this probe (Table 2). We sequenced these PCR products (GenBank accession numbers DQ075265 to DQ075314), and found that 46 (i.e., 92%) were truly derived from subdivision 1 acidobacteria.

Four of the colonies did not appear to originate from members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria. These were members of the classes Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria of the phylum Proteobacteria, of the subclass Actinobacteridae of the phylum Actinobacteria, and of the class Sphingobacteria of the phylum Bacteroidetes. These four sequences did not contain exact binding sites for the AC1-231 probe. It could not be ruled out that these were mixed colonies that contained subdivision 1 acidobacteria as minor components, but this was not investigated. The probe AC1-231 yielded an acceptable number of false-positive signals.

Members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria were not evenly distributed among the colonies that formed under the under different conditions. Experiments carried out with the medium with a pH of 5.5 yielded significantly (χ2 test, P = 0.03) more colonies of subdivision 1 acidobacteria than did the medium with a pH of 7.0 (experiment B in Table 2). There was no significant difference (χ2 test, P = 0.84) between the proportion of subdivision 1 acidobacteria obtained under the replicated incubation conditions using medium VL55 incubated under air in the two different experiments (experiments A and B in Table 2). Similarly, there was no significant difference (χ2 test, P = 0.70) in the cultivation of subdivision 1 acidobacteria in the presence or absence of CO2 (experiment B in Table 2).

Of the 46 colonies confirmed as subdivision 1 acidobacteria, 28, 28, 20, and 24% first became visible in the first, second, third, and fourth month, respectively. There was no significant difference (P = 0.20 to 0.76) between the mean time of visible colony formation by the isolates from any one treatment or experiment. We conclude that, in our hands, pH had a greater effect on the appearance of colonies of subdivision 1 acidobacteria than did CO2. At pH 5.5, 7 to 8% of colonies that formed on plates that were incubated for 4 months were formed by subdivision 1 acidobacteria.

The medium of Stevenson (42), nominally at pH 6.8, dropped significantly (P = 6 × 10−15) to pH 6.24 (standard deviation = 0.02, n = 10) after incubation for 1 week under air containing 5% (vol/vol) CO2 compared to the same medium incubated under air (mean pH, 6.78; standard deviation = 0.04, n = 10). This suggests that pH could have had a significant effect in the experiments reported by Stevenson et al. (42), as suggested in their paper. In contrast, the pH of medium VL55, nominally 5.5, did not change significantly (P = 0.16) when incubated under air containing CO2 (mean pH, 5.44; standard deviation = 0.04, n = 10) compared to medium incubated under air (mean pH, 5.47; standard deviation = 0.04, n = 10).

To test further the effect of pH on colony formation by subdivision 1 acidobacteria, we screened 2,277 colonies that formed on five further growth substrates at pH 5.5 and 7.0 (Table 3). There was no effect of growth substrate choice (P = 0.96, χ2 test), but there was a strong effect of medium pH (P = 6 × 10−12, χ2 test). These tests include the results from experiment B in Table 2, and extend the observation that medium pH plays an important role in allowing colony development by subdivision 1 acidobacteria.

TABLE 3.

Effect of medium pH on colony formation by bacteria hybridizing with probe AC1-231, indicative of members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria

| Growth substratea | Medium at pH 5.5

|

Medium at pH 7.0

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of EUB suite-positive colonies | No. of AC1-231-positive colonies | No. of EUB suite-positive colonies | No. of AC1-231-positive colonies | |

| NAG | 190 | 8 | 221 | 4 |

| GGXA | 172 | 8 | 175 | 3 |

| AA | 197 | 19 | 181 | 2 |

| DNB | 205 | 9 | 187 | 1 |

| CMC | 195 | 20 | 206 | 1 |

| Total | 1,124 | 77 | 1,153 | 16 |

NAG, N-acetylglucosamine; GGXA, mix of glucose, galactose, xylose, and arabinose; AA, amino acid mix; DNB, dilute nutrient broth; CMC, carboxymethyl cellulose.

Diversity of acidobacteria cultured.

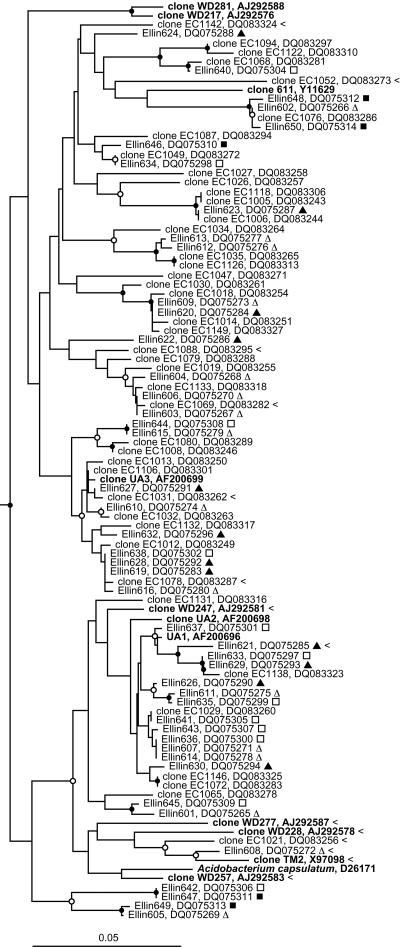

The colonies from the xylan-containing media that were identified as acidobacteria were formed by members of the group spread throughout subdivision 1 and represent almost the entire phylogenetic breadth of the subdivision (Fig. 1). There was significant congruence between the subdivision 1 acidobacteria detected in the clone library and those subsequently isolated (Fig. 1). Many of the clones and isolates were very closely related, as judged by the high degree of 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity. Such a close correlation between cultured and molecularly detected bacteria is rare for high-rank taxa in soils. This shows that the isolation methods employed can culture a broad spectrum of phylogenetically different subdivision 1 acidobacteria representative of those within soil.

FIG. 1.

Evolutionary distance dendrogram of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria based on comparative analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences. The dendrogram was constructed from Jukes-Cantor corrected distances (22) using the neighbor-joining (36) treeing algorithm, and is based on 404 nucleotide positions. The reference sequences were selected to span the phylogenetic breadth of the subdivision (see Sait et al. [35]), and are in bold type. Analyses using different algorithms resulted in very similar dendrograms. The GenBank accession number of each sequence is listed after the sequence name. Isolates from this study are prefixed with Ellin, and the experiment and treatment they are from is indicated by a symbol after the name: Δ, experiment A, pH 5.5 under air; ▴, experiment A, pH 5.5 under air plus CO2; □, experiment B, pH 5.5 under air; ▪, experiment B, pH 7.0 under air. Gene sequences amplified from soil in this study are prefixed with clone EC. Sequences that did not contain a perfect match to probe AC1-231 are indicated by the symbol <. Branch points supported by bootstrap resampling (consensus of 1,000 resampled data sets) are indicated by symbols (•, bootstrap proportion >90%; ○, bootstrap proportion 70 to 90%). Sequences of the subdivision 3 acidobacteria Ellin342 (AF498724) and Ellin371 (AF498753) were used as an outgroup (not shown). The scale bar indicates 0.05 changes per nucleotide.

Only one isolate, Ellin608, was closely affiliated with A. capsulatum. The probe used to detect colonies did not have perfect matches to many close relatives of A. capsulatum (Fig. 1), but this subgroup also appeared to be rare in the soil as judged by the paucity of clones detected. Interestingly, isolate Ellin608 had two mismatches to the probe, indicating that AC1-231 could detect a slightly broader range of acidobacteria than originally anticipated.

Subdivision 1 acidobacteria in different soils.

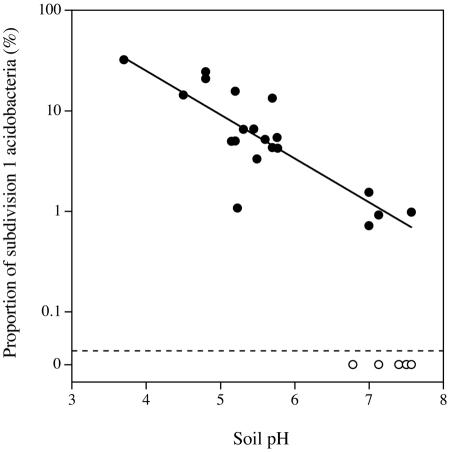

From these experiments it is not possible to state if the preference for subdivision 1 acidobacteria for slightly acidic media is a consequence of culturing them from a soil with a pH of about 5.5 (40), or if members of this subdivision have a general preference for acidic soils. We were able to test this by analyzing data from libraries of 16S rRNAs and 16S rRNA genes from different soils. The proportion of subdivision 1 acidobacteria in these libraries (2, 5, 9-11, 15-17, 25, 27, 28, 31, 34, 43; L. Schoenborn and P. H. Janssen, unpublished) was strongly related (r = 0.834, P < 0.0001) to soil pH (Fig. 2). These bacteria appear to be numerically abundant in soils with pHs below 6, suggesting that they, as a general group, are favored by slightly to moderately acidic conditions in soil as well as in culture. The soils in which no subdivision 1 acidobacteria were detected all had pHs of >6.5.

FIG. 2.

Proportion of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA gene sequences from members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria in 25 libraries from soils as related to soil pH. Libraries in which subdivision 1 acidobacteria were detected (•) were used to calculate the line of best fit, while libraries with no subdivision 1 acidobacteria (○) were omitted from the calculation.

We have found that moderately acidic pHs favor colony development by members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria and that this group is most abundant in clone libraries prepared from microbial communities from soils around the world with acidic rather than neutral pH. We have characterized five phylogenetically diverse members of subdivision 1 of the phylum Acidobacteria and found that all grow optimally at pH 4 to 5.5 and poorly or not at all at a pH of >6.5 (M. Sait and P. H. Janssen, unpublished data). Investigation of a wider range of isolates from this group, from different soils and geographically distant sites, will be required to confirm whether subdivision 1 acidobacteria are generally moderate acidophiles, similar to Acidobacterium capsulatum (24).

Acknowledgments

We thank Cameron Gourley and Sharon Aarons (Dairy Research Institute, Ellinbank) for help with access to the sampling site, Parveen Sangwan and Shayne Joseph for help with some of the cultivation experiments, and Philip Hugenholtz for advice on some of the phylogenetic assignments.

This work was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axelrood, P. E., M. L. Chow, C. C. Radomski, J. M. McDermott, and J. Davies. 2002. Molecular characterization of bacterial diversity from British Columbia forest soils subjected to disturbance. Can. J. Microbiol. 48:655-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barns, S. M., S. L. Takala, and C. R. Kuske. 1999. Wide distribution and diversity of members of the bacterial kingdom Acidobacterium in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1731-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson, D. A., I. Karsch-Mizrachi, D. J. Lipman, J. Ostell, and D. L. Wheeler. 2005. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:D34-D38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borneman, J., and E. W. Triplett. 1997. Molecular microbial diversity in soils from eastern Amazonia: evidence for unusual microorganisms and microbial population shifts associated with deforestation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2647-2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole, J. R., B. Chai, R. J. Farris, Q. Wang, S. A. Kulam, D. M. McGarrell, G. M. Garrity, and J. M. Tiedje. 2005. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): sequences and tools for high-throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:D294-D296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daims, H., A. Bruhl, R. Amann, K.-H. Schleifer, and M. Wagner. 1999. The domain-specific probe EUB338 is insufficient for the detection of all Bacteria: development and evaluation of a more comprehensive probe set. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22:434-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis, K. E. R., S. J. Joseph, and P. H. Janssen. 2005. Effects of growth medium, inoculum size, and incubation time on the culturability and isolation of soil bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:826-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunbar, J., S. Takala, S. M. Barns, J. A. Davis, and C. R. Kuske. 1999. Levels of bacterial community diversity in four arid soils compared by cultivation and 16S rRNA gene cloning. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1662-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunbar, J., S. M. Barns, L. O. Ticknor, and C. R. Kuske. 2002. Empirical and theoretical bacterial diversity in four Arizona soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3035-3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis, R. J., P. Morgan, A. J. Weightman, and J. C. Fry. 2003. Cultivation-dependent and -independent approaches for determining bacterial diversity in heavy-metal-contaminated soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3223-3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5:164-166. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felske, A., W. M. de Vos, and A. D. L. Akkermans. 2000. Spatial distribution of 16S rRNA levels from uncultured acidobacteria in soil. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 31:118-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitch, W. M., and E. Margoliash. 1967. Construction of phylogenetic trees. Science 155:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furlong, M. A., D. R. Singleton, D. C. Coleman, and W. B. Whitman. 2002. Molecular and culture-based analyses of prokaryotic communities from an agricultural soil and the burrows and casts of the earthworm Lumbricus rubellus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1265-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gremion, F., A. Chatzinotas, and H. Harms. 2003. Comparative 16S rDNA and 16S rRNA sequence analysis indicates that Actinobacteria might be a dominant part of the metabolically active bacteria in heavy metal-contaminated bulk and rhizosphere soil. Environ. Microbiol. 5:896-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hackl, E., S. Zechmeister-Boltenstern, L. Bodrossy, and A. Sessitsch. 2004. Comparison of diversities and compositions of bacterial populations inhabiting natural forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5057-5065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallberg, K. B., and D. B. Johnson. 2003. Novel acidophiles isolated from moderately acidic mine drainage waters. Hydrometallurgy 71:139-148. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hugenholtz, P., B. M. Goebel, and N. R. Pace. 1998. Impact of culture-independent studies on the emerging phylogenetic view of bacterial diversity. J. Bacteriol. 180:4765-4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssen, P. H., P. S. Yates, B. E. Grinton, P. M. Taylor, and M. Sait. 2002. Improved culturability of soil bacteria and isolation in pure culture of novel members of the divisions Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2391-2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph, S. J., P. Hugenholtz, P. Sangwan, C. A. Osborne, and P. H. Janssen. 2003. Laboratory cultivation of widespread and previously uncultured soil bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7210-7215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jukes, T. H., and C. R. Cantor. 1969. Evolution of protein molecules, p. 21-132. In H. N. Munro (ed.), Mammalian protein metabolism. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 23.Kishimoto, N., and T. Tano. 1987. Acidophilic heterotrophic bacteria isolated from acidic mine drainage, sewage and soils. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 33:11-25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishimoto, N., Y. Kosako, and T. Tano. 1991. Acidobacterium capsulatum gen. nov., sp. nov.: an acidophilic chemoorganotrophic bacterium containing menaquinone from acidic mineral environment. Curr. Microbiol. 22:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuske, C. R., S. M. Barns, and J. D. Busch. 1997. Diverse uncultivated bacterial groups from soils of the arid southwestern United States that are present in many geographic regions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3614-3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lane, D. J. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p. 115-175. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 27.Liles, M. R., B. F. Manske, S. B. Bintrim, J. Handelsman, and R. M. Goodman. 2002. A census of rRNA genes and linked genomic sequences within a soil metagenomic library. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2684-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipson, D. A., and S. K. Schmidt. 2004. Seasonal changes in an alpine soil bacterial community in the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2867-2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludwig, W., S. H. Bauer, M. Bauer, I. Held, G. Kirchhof, R. Schulze, I. Huber, S. Spring, A. Hartman, and K. H. Schleifer. 1997. Detection and in situ identification of a widely distributed new bacterial phylum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 153:181-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nogales, B., E. R. B. Moore, W. R. Abraham, and K. N. Timmis. 1999. Identification of the metabolically active members of a bacterial community in a polychlorinated biphenyl-polluted moorland soil. Environ. Microbiol. 1:199-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nogales, B., E. R. B. Moore, E. Llobet-Brossa, R Rosello-Mora, R. Amann, and K. N. Timmis. 2001. Combined use of 16S ribosomal DNA and 16S RNA to study the bacterial community of polychlorinated biphenyl-polluted soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1874-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Farrell, K. A., and P. H. Janssen. 1999. Detection of verrucomicrobia in a pasture soil by PCR-mediated amplification of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4280-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rappé, M. S., and S. J. Giovannoni. 2003. The uncultured microbial majority. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:369-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rösch, C., A. Mergel, and H. Bothe. 2002. Biodiversity of denitrifying and dinitrogen-fixing bacteria in an acid forest soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3818-3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sait, M., P. Hugenholtz, and P. H. Janssen. 2002. Cultivation of globally-distributed soil bacteria from phylogenetic lineages previously only detected in cultivation-independent surveys. Environ. Microbiol. 4:654-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Sangwan, P., S. Kovac, K. E. R. Davis, M. Sait, and P. H. Janssen. 2005. Detection and cultivation of soil verrucomicrobia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8402-8410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoenborn, L., P. S. Yates, B. E. Grinton, P. Hugenholtz, and P. H. Janssen. 2004. Liquid serial dilution is inferior to solid media for isolation of cultures representing the phylum level diversity of soil bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4363-4366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh, D. K., P. W. G. Sale, C. J. P. Gourley, and C. Hasthorpe. 1999. High phosphorus supply increases persistence and growth of white clover in grazed dairy pastures during dry summer conditions. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 39:579-585. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sokal, R. R., and F. J. Rohlf. 1969. Biometry. The principles and practice of statistics in biological research. W. H. Freeman and Co., San Francisco, Calif.

- 42.Stevenson, B. S., S. A. Eichorst, J. T. Wertz, T. M. Schmidt, and J. A. Breznak. 2004. New strategies for cultivation and detection of previously uncultured microbes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4748-4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun, H. Y., S. P Deng, and W. R. Raun. 2004. Bacterial community structure and diversity in a century-old manure-treated agroecosystem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5868-5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The ClustalX-Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou, J., B. Xia, H. Huang, D. S. Treves, L. J. Hauser, R. J. Mural, A. V. Palumbo, and J. M. Tiedje. 2003. Bacterial phylogenetic diversity and a novel candidate division of two humid region, sandy surface soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35:915-924. [Google Scholar]