Abstract

Three peptides produced by a Lactobacillus acidophilus DPC6026 fermentation of sodium caseinate and showing antibacterial activity against pathogenic strains Enterobacter sakazakii ATCC 12868 and Escherichia coli DPC5063 were characterized. These peptides were all generated from bovine αs1-casein and identified as IKHQGLPQE, VLNENLLR, and SDIPNPIGSENSEK. These peptides may have bioprotective applicability and potential use in milk-based formula, which has been linked to E. sakazakii infection in neonates.

A number of bioactive peptides have been identified in milk proteins, such as casein and whey proteins, where they are present in an encrypted form, stored as propeptides or mature C-terminal peptides that are only released upon proteolysis (6, 9) The first antimicrobial peptides of casein origin were identified by Hill et al. (8), who isolated antibacterial glycopeptides, known as casecidins. Isracidin αs1-casein f(1-23) [αs1-CN f(1-23), where f(1-23) refers to amino acids 1 to 23 of the peptide], a positively charged antimicrobial peptide with the primary amino acid structure R1PKHPIKHQGLPQEVLNENLLRF23 (8), was shown to have a broad spectrum of activity against gram-positive bacteria (11). Given the highly proteolytic nature of lactic acid bacteria such as Lactococcus lactis (10, 16) and Lactobacillus helveticus (13, 20), it is not surprising that their use as microbial catalysts for the generation of bioactive peptides has been investigated (14). Characterization of peptides produced during casein degradation has been described for L. helveticus (5, 19) and to a lesser extent for Lactobacillus casei (2). Also, the cell wall-bound proteinase of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis ACA-DC 178 has been characterized, and its specificity for β-casein has been documented (17).

The aim of this study was to investigate the potential of Lactobacillus acidophilus DPC6026 to generate antimicrobial peptides from bovine casein and to assess the activities of these peptides against pathogenic bacteria. Two peptide fragments were identified that exhibited antimicrobial activity similar to that of the characterized antimicrobial peptide isracidin against pathogenic strains such as Escherichia coli, Enterobacter sakazakii, Streptococcus mutans, and Listeria innocua, used in this study as a model for the known pathogenic strain Listeria monocytogenes.

L. acidophilus DPC6026 was isolated from the porcine small intestine and stocked in the culture collection of Teagasc Dairy Products Research Centre, Cork, Ireland. This strain was propagated in MRS broth (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) anaerobically for 24 h at 37°C. L. innocua DPC3306, E. sakazakii ATCC 12868, E. sakazakii NCTC8155, purchased from the National Collection of Industrial and Marine Bacteria (Aberdeen, United Kingdom), and E. coli DPC6053 were employed as the test strains.

L. acidophilus DPC6026 was used in fermentation on the basis of its proteolytic capabilities, demonstrated using small-scale (10 ml) casein fermentations followed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. L. acidophilus DPC6026 produced a fermentate in which 11.12% of the peptides were 1 to 2 kDa and 78.23% were ≤1 kDa (data not shown). L. acidophilus DPC6026 was chosen for the generation of antimicrobial peptides in this study because it hydrolyzed sodium caseinate to oligopeptides, the sizes of which are similar to bioactive peptides discovered to date, and because it is classified as generally recognized as safe.

The sodium caseinate substrate (2.5%, wt/vol) was inoculated (1%, wt/vol) with L. acidophilus DPC6026 and incubated at 37°C for 24 h with mixing at 100 rpm at constant pH 7, maintained by the addition of 0.1 M NaOH. Fermentations were performed in triplicate. Cultures were inactivated by being heated to 80°C, and the fermentate was subsequently filtered through a 10-kDa cartridge filter (Millipore Ltd., Hertfordshire, United Kingdom). Peptides of <10 kDa were separated using reverse-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) as described previously (5). Solvents were removed from the collected fractions by Centrivap evaporation (Labconco Corporation, Kansas City, Mo.), and protein concentration was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay (12).

Characterization of the antibacterial activity of fractions involved measurement of growth inhibition in a 96-well plate assay (4) and utilization of an agar diffusion method (7). Cecropin P1 and indolicidin were used as positive controls, as the latter is chiefly active against gram-positive bacteria, while the spectrum of activity of cecropin P1 is mainly against gram-negative bacteria, making both controls suitable for use against the spectrum of bacteria analyzed in this study. The plates were incubated for 6 h at 37°C, and culture growth was monitored hourly. MICs of the peptides were taken as the lowest concentration without visible growth, measured by recording the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) in a microtiter plate reader. A well diffusion assay was performed as described previously (7), using the indicator strains E. coli DPC6053, L. innocua DPC3306, E. sakazakii ATCC 12868, or E. sakazakii NCTC8155 to detect antibacterial activity of purified peptides. The sensitivity of a strain to the peptides was scored according to the diameter of the zone.

Protein fractions exhibiting antibacterial activity were refractionated under RP-HPLC conditions as described above, and the purified peptide composition was analyzed by mass spectrometry with a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrophotometer (PE Biosystems Voyager-DE STR Biospectrometry Workstation, Aberdeen Proteome Facility). The amino acid sequences of the purified peptides in each fraction were determined after derivatization and Edman degradation performed on a 494A protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems). All purified peptide sequences identified (by mass spectrometry analysis and amino acid sequencing) in each fraction exhibiting antimicrobial activity were subsequently chemically synthesized by Peptide Protein Research Ltd. (Fareham, United Kingdom) to ensure that the sequence identified by MALDI-TOF analysis was responsible for the antibacterial activity within the fractions. Chemically synthesized peptides and RP-HPLC purified fractions exhibiting antimicrobial activity against E. coli DPC6053 were tested for susceptibility to proteinase K (Sigma). The positive controls used were the peptides isracidin and cecropin P1 (Sigma) as their spectrum of activities are chiefly against gram-negative bacteria (1).

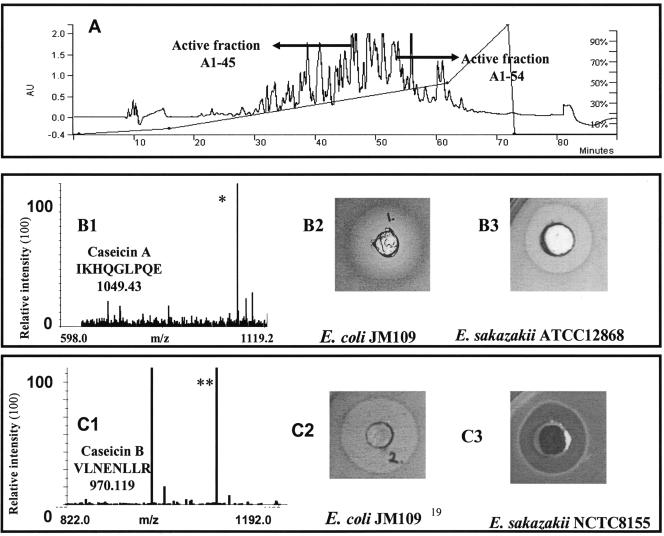

The fractions produced by L. acidophilus DPC6026 fermented in sodium caseinate and purified using RP-HPLC possessed antibacterial activity; however, antimicrobial activity was not detected in the fermentate, which was not filtered through a 10-kDa membrane, using either the 96-well plate assay or the well diffusion assay against any of the indicator strains. This result demonstrates that fractionation of peptides on the basis of size and charge produced fractions having improved antimicrobial properties. It suggests that electrostatic interactions between charged peptides may have a negative effect on the antimicrobial activity of the fermentate and that activity was improved by membrane filtration and RP-HPLC, which reduced these charges by reducing the peptide content present in the fermentate to ≥10 kDa and also by separating the peptides into fractions, thereby reducing interactions and improving antimicrobial activity. Three fractions, A1-45, A1-49, and A1-54 (Fig. 1A), exhibited the most potent antibacterial activity against E. coli DPC6053 and had peptide concentrations of 0.554 mg/ml, 0.5 mg/ml, and 1.24 mg/ml, respectively. The antimicrobial peptides contained in the three fractions and their calculated masses and corresponding sequences are reported in Table 1. The peptide αs1-CN f(21-29), IKHQGLPQE (caseicin A), present in fraction 45 inhibited the indicator organism, E. coli DPC6053, at a concentration of 0.05 mM (Fig. 1B). Caseicin A also inhibited pathogenic bacteria such as E. coli O157:H7 derivatives (E. coli DPC6054 and E. coli DPC6055) and E. sakazakii ATCC 12868 (Fig. 1B) also at 0.05 mM. The peptide αs1-CN f(30-37), VLNENLLR (caseicin B), present in fraction 54 inhibited E. coli DPC6053 and E. sakazakii DPC6091 at a concentration of 0.22 mM (Fig. 1C), while fraction A1-49 (caseicin C) containing the peptide SDIPNPIGSENSEK displayed only minor inhibitory activity against L. innocua DPC3306 but no activity against E. coli DPC6053 (Table 2). No activity was detected for caseicin A, B, or C against the gram-positive pathogenic strain Staphylococcus aureus DPC5246, despite the fact that the precursor peptide isracidin is documented as displaying antimicrobial activity against S. aureus strains in vivo (11). Lack of antimicrobial activity could be due, first, to the concentrations of the peptides used in the in vivo study which are documented as being relatively high (1.0 mg/ml) (11). Second, the lack of activity observed could be related to the cleavage of isracidin into caseicins A and B. Both of the latter peptides identified in this study lack the N-terminal amino acid sequence RPKHP [isracidin f(1-5)] of isracidin, which could be responsible for the activity of this precursor peptide against S. aureus demonstrated in vivo in sheep (11).

FIG. 1.

(A) RP-HPLC chromatogram of sodium caseinate at pH 7 incubated with L. acidophilus DPC6026 for 24 h. Arrows indicate the positions of peptide fractions A1-45 and A1-54. RP-HPLC was carried out at room temperature and under the conditions described in Materials and Methods. (B1) MALDI-TOF spectrum of fraction A1-45 (isolated using sodium caseinate as the substrate and the strain L. acidophilus DPC6026) recorded in the m/z region where peptides were detected. Peptide fraction A1-45 was found to contain a peptide of mass 1,049.43 (indicated by *), which was found after sequencing to be IKHQGLPQE, which corresponds to αs1-CN f(21-29). Insets show inhibition of E. coli DPC6053 (B2) and E. sakazakii 5920 (ATCC 128682) (B3) by the chemically synthesized peptide IKHQGLPQE. A zone 2.5 cm in diameter was recorded using the agar well diffusion assay method. (C1) MALDI-TOF spectrum of fraction A1-54 (isolated using sodium caseinate as the substrate and the strain L. acidophilus DPC6026) recorded in the m/z region where peptides were detected. Peptide fraction A1-54 was found to contain a peptide of mass 970.119 (indicated by **), which was found after sequencing to be VLNENLLR, corresponding to αs1-CN f(30-37). Insets show inhibition of E. coli DPC6053 (C2) and E. sakazakii 8272 (C3) by the chemically synthesized peptide VLNENLLR, identified in fraction A1-54 of the sodium caseinate hydrolysate with L. acidophilus DPC6026. A zone 1.5 cm in diameter was recorded using the agar well diffusion assay method.

TABLE 1.

Sequences and corresponding CN fragments of peptides contained in crude fractions from sodium caseinate hydrolysates produced by L. acidophilus DPC6026

| Sequence and CN fragment | Fraction | Overall charge | Chain lengtha | Calculated mass (m/z) | Expected mass (m/z)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IKHQGLPQE, αs1-CN f(21-29) | A1-45 | Positive | 9 | 1,049.177 | 1,049.43 |

| VLNENLLR, αs1-CN f(30-37) | A1-54 | Positive | 8 | 970.119 | 970.119 |

| SDIPNPIGSENSEK, αs1-CN f(195-208) | A1-49 | Positive | 14 | 1,486.536 | 1,486.7 |

Number of amino acid residues.

Average masses are reported for the expected mass of each peptide.

TABLE 2.

The inhibitory spectrum of pure peptides synthesized following fermentation of L. acidophilus DPC6026 in sodium caseinate

| Indicator species | Strain designationa | Degree of inhibition of peptideb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence and CN fragment

|

Isracidin | Cecropin P1 | Indolicidin | ||||

| IKHQGLPQE, αs1-CN f(21-29) | VLNENLLR, αs1-CN f(30-38) | SDIPNPI G SENSEK, αs1-CN f(195-208) | |||||

| S. aureus | DPC5246 | − | − | − | −/+ | +++ | − |

| E. coli JM109 | DPC6053 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | +++ | − |

| E. coli O157:H7 | DPC6054 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | +++ | − |

| E. coli O157:H7 | DPC6055 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | +++ | − |

| E. sakazakii ATCC 12868 | DPC6090 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | +++ | − |

| E. sakazakii NCTC 8155 | DPC6091 | +++ | +++ | − | +++ | +++ | − |

| L. innocua | DPC3306 | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + |

| L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 | DPC5383 | +++ | +++ | − | ++ | ++ | + |

| S. mutans | DPC4069 | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | + |

Dairy Products Research Centre, Cork, Ireland.

The diameters of the zones of inhibition were as follows: +++, 1.5 cm < diameter ≤ 2.0 cm; ++, 1.0 cm < diameter ≤ 1.5 cm; +, ≤ 0.5 cm diameter ≤ 1.0 cm; −/+, diameter < 0.5 cm (minor zone); −, no zone detected.

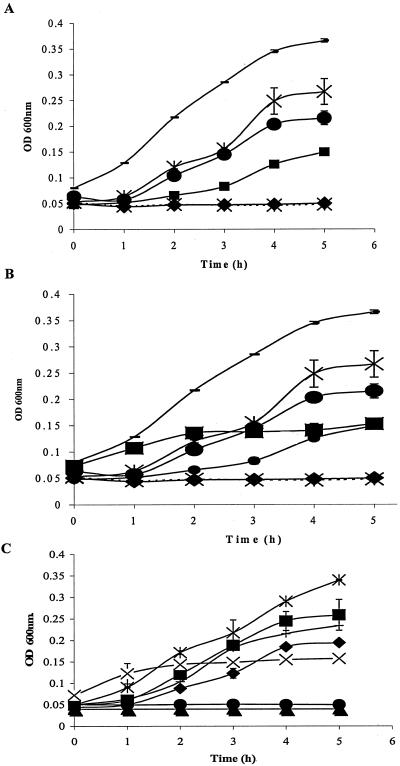

Chemically synthesized caseicins A and B inhibited the same microorganisms as the fractions containing these peptides while caseicin C displayed only minor inhibitory activity against L. innocua DPC3306 and no activity against E. coli DPC6053 (Table 2). The MIC of these peptides was determined using isracidin as a positive control. Data points as indicated in Fig. 2 were calculated as the average values resulting from three different sets of assay results. Isracidin was added as a positive control for determination of the MIC since, first, it is a well-documented antimicrobial peptide (11) and, second, caseicins A and B display sequence homology with isracidin, suggesting that this positively charged peptide may be the precursor of caseicins A and B, making it a suitable positive control for comparison of MIC data. Isracidin inhibited E. coli DPC6053 at concentrations ranging from 0.05 mM to 1.9 mM (Fig. 2A), where inhibition is defined as a reduction in the growth rate of the test strains measured at OD600 with different concentrations of the test peptide(s) added, relative to the growth rate of the test strains without any peptide(s). These values were then compared to the positive control isracidin. The MIC of isracidin was found to be 0.059 mM under the experimental conditions described, while the MIC of caseicin A was 0.078 mM against E. coli DPC6053 (Fig. 2B); caseicin B inhibited this microorganism at concentrations ranging from 0.22 mM to 1.2 mM, with an MIC of 0.22 mM (Fig. 2C). The potency of isracidin and cecropin P1 compared to caseicins A, B, and C was 0.059 mM and 0.52 mM, respectively, under the experimental conditions described above; the MICs are compared in Table 3. Under assay conditions, all the chemically synthesized peptides and crude fractions lost their antimicrobial activity when they were treated with proteinase K. Using the computer program Expasy peptide cutter (http://us.expasy.org/tools/peptidecutter/), it was found that caseicins A, B, and C are hydrolyzed by trypsin and chymotrypsin.

FIG. 2.

(A) Effect of isracidin at various concentrations on the OD600 of E. coli DPC6053 (an overnight culture diluted 1:10 with LB broth) using the 96-well plate assay. Cecropin P1 is used as a control peptide. ▪, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with cecropin P1 (0.52 mM); —, E. coli DPC6053 control with no additions; ⧫, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with isracidin (1.9 mM); x, sterility control (LB broth with no additions), • E. coli DPC6053 incubated with isracidin at a concentration of 0.23 mM; X, viability of E. coli DPC6053 incubated with isracidin (0.059 mM). (B) Effect of peptide IKHQGLPQE at various concentrations on the OD600 of E. coli DPC6053 (an overnight culture diluted 1:10 with LB broth) using the 96-well plate assay. —, E. coli DPC6053 with no additions; X, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with IKHQGLPQE (0.078 mM); ▪, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with cecropin P1 (0.52 mM); •, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with IKHQGLPQE (0.15 mM); •, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with IKHQGLPQE (0.31 mM); ⧫, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with IKHQGLPQE (0.625 mM); x, sterility control (LB broth with no additions). (C) Effect of peptide VLNENLLR at various concentrations on OD600 of E. coli DPC6053 (an overnight culture diluted 1:10 with LB broth) using the 96-well plate assay. ×|, E. coli DPC6053 with no additions; ▪, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with VLNENLLR (0.22 mM); —, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with VLNENLLR (0.45 mM); ⧫, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with VLNENLLR (1.2 mM); X, viability of E. coli DPC6053 incubated with cecropin P1 (0.52 mM); •, E. coli DPC6053 incubated with VLNENLLR (2.5 mM); ▴, sterility control (LB broth without additions).

TABLE 3.

MICs of caseicin A, caseicin B, caseicin C, and the control peptides isracidin and cecropin P1 for E. coli DPC6053

| Sequence and CN fragment | Peptide name | MIC (mM) |

|---|---|---|

| IKHQGLPQE, αs1-CN f(21-29) | Caseicin A | 0.05 |

| VLNENLLR, αs1-CN f(30-37) | Caseicin B | 0.22 |

| SDIPNPIGSENSEK, αs1-CN f(195-208) | Caseicin C | 1.0 |

| RPKHPIKHQGLPQEVLNENLLRF, αs1-CN f(1-23) | Isracidin | 0.059 |

| SWLSKTAKKLENSAKKRISEGIAI AIQGGPR | Cecropin P1 | 0.52 |

Caseicin A, caseicin B, and caseicin C identified in this study have not been reported previously as possessing antimicrobial activity (3, 18); however, they have several features in common with other reported antibacterial peptides. The antimicrobial peptide isracidin has a broad spectrum of activity (11) and was used as a positive control in the current study because of its high degree of homology with caseicin A and caseicin B. Caseicin A consists of nine amino acid residues, representing amino acids 6 to 14 of isracidin, while caseicin B consists of eight residues at the C-terminal end of the peptide (amino acid residues 15 to 23). The MICs of caseicin A and caseicin B were comparable to those of isracidin, cecropin P1, and indolicidin. Caseicin A has a positive charge of +2, contains both hydrophobic (isoleucine) and hydrophilic (glutamate) amino acids, and displays better activity against gram-negative bacteria such as E. sakazakii and E. coli than against gram-positive bacteria. Caseicin B also appears to share a number of features in common with other antimicrobial peptides. Using the program Expasy peptide cutter, bovine αs1-CN was hydrolyzed by a combination of three endopeptidases and proteinases to release the antibacterial peptides caseicins A and B.

E. sakazakii has been recognized as the cause of a distinctive syndrome of meningitis in neonates, and there is compelling evidence that milk-based infant formula has served as a reservoir of infection (15). The possibility of using antimicrobial peptides such as caseicin A and caseicin B derived from milk proteins as an in-built mechanism of protection against pathogenic strains such as E. sakazakii ATCC 12868 raises the potential of producing a casein-based milk ingredient through fermentation.

This study shows that L. acidophilus DPC6026 is suitable for the generation of multiple antimicrobial peptides from casein and that sodium caseinate fermentates produced using L. acidophilus DPC6026 may have bioprotective applications in milk food products against both gram-positive and gram-negative undesirable bacteria.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Helen Slattery for technical assistance; Eoin Barrett, Teagasc, Moorepark Food Research Centre, for assistance with pulse-field gel electrophoresis; and Ian Davidson, University of Aberdeen, for mass spectrum analysis and sequencing work.

The Irish Government funded this work under the National Development Plan, 2000-2006, the European Research and Development Fund, and Science Foundation Ireland (SFI). M. Hayes is in receipt of a Teagasc Walsh Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boman, H. G., B. Agerberth, and A. Boman. 1993. Mechanisms of action on Escherichia coli of cecropin P1 and PR-39, two antibacterial peptides from pig intestine. Infect. Immun. 61:2978-2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Palencia, F., P. C. Pelaez, C. Romero, and M. C. Martin-Hernandez. 1997. Purification and characterisation of the cell wall proteinase of Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei IFPL 731 isolated from raw goats milk cheese. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45:95-97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dziuba, J., P. Minkiewicz, D. Natecz, and A. Iwaniak. 1999. Database of biologically active peptide sequences. Nahrung 43:190-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falla, T. J., D. N. Karunaratne, and R. E. Hancocks. 1996. Mode of action of the antimicrobial peptide indolicidin. J. Biol. Chem. 271:19298-19303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gobbetti, M., P. Ferranti, E. Smacchi, F. Goffredi, and F. Addeo. 2000. Production of angiotensin-I-converting-enzyme-inhibitory peptides in fermented milks started by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus SS1 and Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris FT4. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3898-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gobbetti, M., L. Stepaniak, M. De Angelis, A. Corsetti, and R. Di Cagno. 2002. Latent bioactive peptides in milk proteins: proteolytic activation and significance in dairy processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 42:223-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hickey, R. M., D. P. Twomey, R. P. Ross, and C. Hill. 2003. Production of enterolysin A by a raw milk enterococcal isolate exhibiting multiple virulence factors. Microbiology 149:655-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill, R. D., E. Lahov, and D. Givol. 1974. A rennin-sensitive bond in alpha-S1 β-casein. J. Dairy Res. 41:147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamysu, W., M. Okroj, and J. Lukasiak. 2003. Novel properties of antimicrobial peptides. Acta Biochim. Pol. 50:236-239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunji, E. R., G. Fang, M. Jeronimus-Stratingh, A. P. Bruins, B. Poolman, and W. N. Konings. 1998. Reconstruction of the proteolytic pathway for use of beta-casein by Lactococcus lactis. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1107-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahov, E., and W. Regelson. 1996. Antibacterial and immunostimulating casein-derived substances from milk: casecidin, isracidin peptides. Food Chem. Toxicol. 34:131-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macart, M., and L. Gerbaut. 1982. An improvement of the Coomassie blue dye binding method allowing an equal sensitivity to various proteins: application to cerebrospinal fluid. Clin. Chim. Acta 122:93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin-Hernandez, M. C., A. Alting, and F. Exterkate. 1994. Purification and characterisation of the mature, membrane-associated cell-envelope proteinase of Lactobacillus helveticus L89. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 40:828-834. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meisel, H. 2005. Biochemical properties of peptides encrypted in bovine milk proteins. Curr. Med. Chem. 12:1905-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nazarowec-White, M., and J. M. Farber. 1997. Thermal resistance of Enterobacter sakazakii in reconstituted dried infant formula. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 24:9-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pritchard, G. G., and T. Coolbear. 1993. The physiology and biochemistry of the proteolytic system in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:179-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsakalidou, E., R. Anastasiou, I. Vandenberghe, J. van Beeumen, and G. Kalantzopoulos. 1999. Cell-wall-bound proteinase of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis ACA-DC 178: characterization and specificity for β-casein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2035-2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, Z., and G. Wang. 2004. APD: the antimicrobial peptide database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:590-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto, N., A. Akino, and T. Takano. 1994. Antihypertensive effect of the peptides derived from casein by an extracellular proteinase from Lactobacillus helveticus CP790. J. Dairy Sci. 77:917-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zevaco, C., and J. C. Gripon. 1988. Properties and specificity of a cell-wall-associated proteinase from Lactobacillus helveticus CP790. Lait 68:393-408. [Google Scholar]