Abstract

Purposes

This paper proposes both a model and a measure of human service integration through strategic alliances with autonomous services as one way to achieve comprehensive health and social services for target populations.

Theory

Diverse theories of integrated service delivery and collaboration were combined reflecting integration along a continuum of care within a service sector, across service sectors and between public, not-for-profit and private sectors of financing services.

Methods

A measure of human service integration is proposed and tested. The measure identifies the scope and depth of integration for each sector and service that make up a total service network. It captures in quantitative terms both intra and inter sectoral service integration.

Results

Results are provided using the Human Service Measure in two networks of services involved in promoting Healthy Babies and Healthy Children known to have more and less integration.

Conclusions

The instrument demonstrated discriminate validity with scores correctly distinguishing the two networks. The instrument does not correlate (r=0.13) with Weiss (2001) measure of partnership synergy confirming that it measures a distinct component of integration.

Discussion

We recommend the combined use of the proposed measure and the Weiss (2001) measure to more completely capture the scope and depth of integration efforts as well as the nature of the functioning of a service program or network.

Keywords: collaboration, integration, health and social services, measurement

Introduction

Traditionally, human services have been funded to serve specific client needs, in isolation from other client needs and from other services [14]. It has been suggested that human service interventions that address single problems or single risk or protective factors in isolation will be less effective in reducing problems and enhancing competencies than comprehensive interventions. Comprehensive interventions address multiple risk and protective factors, operate across multiple environments such as school, home and the community, provide a mix of universally targeted and clinical services and are often pro-active [2] Recently, the integration of health services has been promoted in an attempt to provide comprehensive health interventions. Service integration as used in this paper, is the term used to describe types of collaboration, partnerships or networks whereby different services that are usually autonomous organizations, work together for specific community residents to improve health and social care. In order to work together effectively, they each may incur resource costs.

The literature talks about collaboration, partnership synergy, and network effectiveness which all are included in our definition of integration. A majority of the recent relevant literature describes the integration of health services [9, 11, 19, 22], or a specific health service such as primary care [15], hospital care [9], or mental health care [16]. Moreover, much of the discussion has been framed under the notion of continuity of care [5, 8]. The term, continuity of care, as used in this paper means the continuation of services from different points in time from prevention or screening, to identification and treatment.

Many communities have approaches to fostering health service integration and some have tried to measure their level of service integration. Communities are looking at how to partner a mix of community services, which would be a function of the total set of needs of a target population, and available human services. The emphasis on integrating human services is the result of an accumulation of evidence that the determinants of health are factors (as well as genetic endowment) that are social, environmental, educational and personal in nature. The fact that proactive, comprehensive services are more effective in achieving targeted health outcomes and less expensive from a societal perspective is because giving people what they need results in a reduced use of other services [3]. However, the fact that current health, education, social, leisure, faith and correctional services are funded as separate entities by autonomous agencies means there are additional barriers to integration.

Most initiatives to integrate services in human health remain single program based, rather than systemic. Some innovative new programs (e.g. Sure Start (UK), Healthy Babies, Healthy Children (ON, Canada)) have integrated services in two or more service areas (health and social service) and achieved complementary universal and targeted early intervention. However, these programs are not typically linked to remedial or clinical services.

Some jurisdictions are also experimenting with innovative funding regimes. In the United Kingdom, geographic areas designated Health Action Zones receive block funding for health, education, social, and other services. Providers are expected to partner and collaborate to provide comprehensive, efficient services with these funds, and any savings are kept within the Health Action Zone [1]. In Ontario's Healthy Babies, Healthy Children program and Early Years initiative, the government funds and legislates policy for the programs, while each community develops its own methods of integrating relevant existing local services. Whether these programs and initiatives will indeed be integrated remains unclear, and thus a measure that could quantify the integration success would be helpful.

Integration models assume that human service entails the presence of some formal integration mechanism(s). Such mechanisms may be formal networks, committees or coalitions of local agencies, organizations, and possible funders, charged with planning, organizing and delivering comprehensive local human services. However, in many communities frontline service providers and managers often collaborate informally with their counterparts in other agencies or programs to give clients the necessary mix of cross-sectoral, intra-sectoral and continuum of services.

Provan and Milward [12] argue that networks' success in integrating human services should be assessed from three perspectives, those of: (a) network members or integrated service providers themselves (administrators and service providers), (b) service users, and (c) community members such as politicians, funders and other residents. They identify potential stakeholder groups to assess success in integration, and criteria for success that would be relevant to each group's perspective. Additional measures would be needed to look at the outcomes of service integration, including aggregate measures of community well being, and clients' health and social well being.

Examples of integration efforts are given in the literature. In the US, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Program on Chronic Mental Illness established citywide local mental health authorities. These authorities sought to improve services and continuity of care at the provider level for all persons with chronic mental illness by localizing administrative, fiscal, and clinical responsibility [7]. Lehman et al. [10] evaluated this program by interviewing cohorts of participants in four cities and reported differences in care provision but no difference in client outcome in the 12-month study period. Neither the scope nor the depth of integration was measured.

Weiss et al. [20] developed a questionnaire for identifying partnership synergy and dimensions of partnership functioning that influence it. It assesses the degree to which a partnerships' collaborative process successfully combines its participant's perspectives, knowledge and skills. This helps partners identify at an early stage whether they are making the most of the collaborative process. Partnership synergy is thought to be the primary characteristic of a successful collaborative process. The dimensions of this questionnaire were: Partnership Synergy; Partnership Efficiency; Problem with Partner Involvement; Effectiveness of Leadership; Effectiveness of Administration/Management; Adequacy of Resources; Difficulties Governing the Partnership; and Problems Related to the Community.

Weiss et al. [21] conducted the National Study of Partnership Functioning in the US. Results indicated that higher levels of partnership synergy, a term used to describe how well a partnership is functioning, were related to more effective leadership and greater partnership efficiency. The results also suggested a relationship to more effective administration and management as well as to greater sufficiency of non-financial resources.

Recently, Medical Care Research and Review produced a special supplement on community partnerships and collaboration in December 2003. In the Community Care Network (CCN) demonstration project of 25 partnership sites in the US (Easterling 2003), Hasnain–Wynia et al. examined which partnerships were perceived by their partners as being most effective and essential in improving community health; Bazzoli et al. analyzed how fully the different partnerships implemented their planned action steps; Conrad et al. looked at the degree to which the various sites of partnerships were able to affect the local health care system in terms of access, quality and cost as well as health outcomes; and Alexander et al. investigated the factors that allowed a partnership to establish a high versus low potential for sustainability. None measured the scope or depth of the integration in a more objective manner.

In summary, integration or collaboration has been described and discussed in the literature. Some programs that have integrated services have studied their functioning, client outcomes have been measured, and a questionnaire for identifying partnership synergy and the parts of the integration effort that are working well has been developed [20]. The importance of evaluating the network (integrated services), has been outlined and the components of an evaluation have been discusses by Provan and Milward [12]. However, no measure was found in the literature that would assist the evaluator in identifying which partner agencies communication and decision-making were strong or weak. A measure was needed that outlines the extent or number of services being integrated from which sectors and which sectors and/or services show strong or weak depths of integration.

New contribution

This paper makes a new contribution to the service integration literature. It describes a three-dimensional model of service integration and then introduces a new measure of human services integration that quantifies the extent, scope and depth of the effort. It identifies which sectors, services or agencies are connected and are collaborating well with each other and which sectors and/or agencies in the network could enhance their collaborative efforts.

A model of human services integration

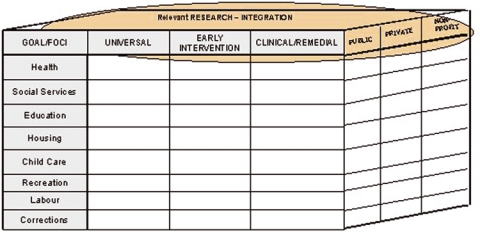

Figure 1 shows a three-dimensional model of integration, developed by the authors, which can be used to understand integration among human services. The model is applied to services for families and young children as an example. On the vertical axis, the model identifies eight sectors to be integrated. A sector is defined as an area of health or social care that is usually grouped together in communities, often due to funding regulations and historical activities in a community. In this example, health, social services, education, housing, childcare, recreation, labor, and correctional/custody services are the identified sectors. The horizontal axis identifies the three types of services that together provide a continuum of service: universal (prevention), targeted (early intervention), and clinical (family development support, remedial, and therapeutic). The third axis of the model identifies three main sources of funding and other resources to be integrated: public, private, and non-profit or voluntary.

Figure 1.

A model of integration, applied to services for families with young children.

This model can be used in any setting to identify the level of total and partial integration of human service along each of the three dimensions, or axes. It also permits analysis of the level of total and partial integration of human service across the three axes together, or across any two axes in any given setting. It identifies sectors or services missing from collaborative networks.

To have comprehensive services, communities often require integration across the entire field of human services. Integration conducive to comprehensive human services would include all three axes; cross-sectoral integration, continuum of service and funding integration. Cross-sectoral integration requires coordination among different service sectors including health, education, social and recreation, to provide interventions at all important points and facets of individuals' lives, and in multiple environments. Continuum of service requires coordination among services and programs within any given sector where universal screening services are linked to early intervention and clinical/remedial services when needed. Such a continuance of service bridges program, disciplinary and other boundaries and achieves a unified mix of universal, targeted and clinical services. Funding integration may require pooling of all resources (human and material, from public, private, non-profit and volunteer sectors) to facilitate and encourage cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary integration in publicly funded systems [4].

Comprehensive community services should be integrated at the point of delivery. Evidence does not suggest that sectors need to be merged, or community agencies amalgamated, in order to achieve integration at delivery. On the contrary, research on integration of school-aged programs in Ontario has identified ‘funding, turf and autonomy’ as a description for key points about responsibility that make integration challenging [18]. The task of implementing cross-sectoral, intra-sectoral, and funding integration of human services can be daunting, given the number of services and their differing bureaucratic structures, mandates, levels of expertise, professionalism, and funding mechanisms. Volpe et al. [18] found that three factors were key to achieving the organizational change needed to overcome ‘funding, turf and autonomy’ barriers to integrated school-linked children's services: supportive policies and funding, institutional leadership, and a climate of trust to overcome parochialism.

Measuring success in integration

Using Provan and Milwards's [12] perspectives for evaluation, we developed a tool for evaluating integration from one of their perspectives, which was from the network members. We determined that an ideal measure of a successful integration of community services would identify where the strengths of the partnership were, would quantify the extent, scope and depth of the integration services and funders, and would indicate which services and funders were or were not integrating or collaborating well. In this paper, we describe a measure to quantify the level of integration as seen by the network members. There are other measures that measure how the integration is working and what about the integration is working well or not, such as the partnership synergy questionnaire developed by Weiss et al. [20]. Additionally, other outcome measures could be used to determine the effect of the integration effort on the residents of the community, such as effects of the integration of the services on residents' health, social functioning, and on the costs of health and social service use by participants served and the target population in the community.

Human services integration measure

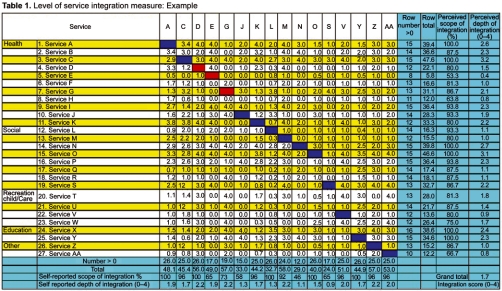

Representatives of the services in the partnership completed this Human Service integration Measure, a measure that was developed to quantify the extent, scope and depth of integration as perceived by local service providers. The measure provides a quantitative integration measure for each service and a total integration measure of the level of service integration. This measure developed in an EXCEL form ( Table 1) identifies specific services in the left hand column that are participating in a program of care. It identifies three aspects of integration:

Extent of integration: the identification of services and the number of services within a number of programs or sectors involved in the partnership

Scope of integration: the number of services that have some awareness or link with others

Depth of integration: the depth of links among all services and each service, along a continuum of involvement where non-awareness=0, awareness=1, communication=2, coordination=3, collaboration=4.

Table 1.

Level of services integration measure: Example

How to use the measure

Representatives or coordinators from each service from each sector, listed in the left hand column are asked to rate the depth of their integration with each of the other services on the list. The depth of integration is scored using an ordinal scale developed by Narayan and Shier for Ontario's Better Beginnings, Better Futures program (reported in [17]), and also used by Ryan and Robinson [13] in evaluating the Healthy Babies, Healthy Children HBHC program. The ordinal scale articulates a five-domain continuum of increasing integration (0–4):

0=No awareness: program or services are not aware of other programs or services.

1=Awareness: discrete programs or services in the community are aware of other programs or services, but they organize their own activities solely on the basis of their own program or service mission, and make no effort to do otherwise.

2=Communication: programs and services actively share information and communicate on a formal basis.

3=Cooperation: programs or services modify their own service planning to avoid service duplication or to improve links among services, using their knowledge of other services or programs.

4=Collaboration: programs or services jointly plan offered services and modify their own services as a result of mutual consultations and advice.

The service coordinators' depths of integration ratings can be gathered by telephone interview, web-form, in person, or during workshops. Each response is entered in the box in the column headed with the service number, across from the row with the name of the other service being rated.

Pilot test of the human services integration measure

We applied our model of human services integration and administered the Human Services Integration Measure to two children's programs: the HBHC program in one region, and the Early Years program within another region of the Province of Ontario, Canada in order to measure the integration among service agencies affiliated with each program. HBHC provides universal services such as screening and assessment and post-partum contacts to all mothers with newborns, as well as intensive targeted services to families with children at high risk of poor development. The HBHC program in the provincial health region was required to create a formal network (or to link with an existing network) whose mandate included integration of local health, social, childcare/recreation/education and other services for families and young children, along a continuum of service. The Early Years program provides health and social services to families and their children and was required to create a network with all agencies involved in preschool and school age children services.

The health regions measured covered an expansive rural and urban area, including an aboriginal population. The chair of each program (HBHC or Early Years) was asked to identify all services participating in the HBHC Coalition or the Early Years Group. The agencies that participated included groups from health (public health nurses, lay home visitors, infant development programs, health centres, midwives, hospitals and community coordination centres); social (family and community services, children's aid societies, early year centres, head start family resource centre, national community action for children program); recreation/child care (teen centre, child care centres); education (Public and Catholic; English and French school boards); and other community resources (food banks, united way, the Faith Community).

Scoring the integration measure

The scoring of the measure using an example of data from a Children's partnership is shown in Table 1. Each representative from a specific service within a specific sector completing the measure has his/her service number listed across the top row. The left hand column lists all the services in the network or partnership. The numbers of each service in this column corresponds to the numbers across the top row. Service representatives then rate their collaboration efforts as perceived by themselves from 0 to 4, for each of the other services. This rating number is put under their column number beside each service being rated. For example, Service M (#13) across the top row (also Service M (#13) down the left hand column) reports a 4 (collaboration) with Service D (#4). A 4 is then entered in the fourth box of the column under #13.

Response Rate is the number of respondent services, as a percentage of all services listed in the measure. In our example, the response rate was 59% since 16 services were listed across the top row out of 27 services listed down the left hand column. At the workshop, where this instrument was given, 16 services had one or more representatives attending who completed the form. It is recommended that follow up be done to get service non-attendees to complete the measure and improve the response rate. This follow up could be done by phone, mail or e-mail in order to increase the response rate. This would reduce bias, as those attending a workshop may be systematically different than those not attending. Each agency chose their service representative. Most often this representative was the member felt to be most knowledgeable about their program (executive director or program manager). If multiple representatives of a program or service respond, scores are averaged.

Extent of Service Integration Score measures the number of local services and sectors in the community participating in a program of care. The score was 27 services. Of interest is how many were in each of the sectors of health, social, recreation, education or other. This description allows the network or partnership members or other stakeholders to examine and debate whether this is appropriate for their partnership/network or are their important sectors of services missing from tier network.

Scope of Integration Scores includes two scope of integration scores for individual services listed in the integration measure:

Perceived Scope of Integration Score measures the extent to which other services listed are at least aware of a particular service. The score is the percentage of services given 1 or higher by other service providers.

Self-Reported Scope of Integration Score measures the extent to which a service is at least aware of other services. The score is the percentage of services assigned a score of 1 or higher, in the column headed by the service's number.

In our example, the column for service D (#4) reports awareness or more (score≥1) in 26 of the 26 other services listed in the matrix. No boxes in the column are empty, therefore, the self-reported scope of integration score is 100%. The perceived scope of integration score, however, is 80% since 12 of the other services listed in the matrix (out of 15 who completed the form) report awareness or more of Service D. Service D was given a score of 0 by services #7, #14, and #19.

Depth of Integration Scores includes two depth of integration scores for individual services listed in the integration measure:

Perceived Depth of Integration Score measures the depth of a service's integration with each of the other services, as perceived by these other service providers. Individual categories can be noted for each service. Also, the combined score is the average of these scores in the row. Thus, each service can see the response category from “non awareness to collaboration” that is assigned by the other services. A service may be interested in how many in each category they have. In addition, the mean score is valuable.

Self-Reported Depth of Integration Score measures the depth of a service's integration with other services of which it is aware. This ordinal score is associated with a category related to level of integration and is meaningful for each service to examine how many services it has in each response category. In addition, averaging the numbers in the column headed by the service's number derives a mean score for that service, indicating a composite score.

In our example, the self-reported depth of integration score for Service D (#4) is 2.2. The total (56) is divided by the number of boxes (26). The perceived depth of service, the scores given by others, for Service D is only 1.5. This score is obtained by adding the scores in the Service D row (22.1) and dividing by the number services across the top (15). Even if a service was not represented at the workshop and did not complete the form, they still have a depth and scope score as perceived by the others.

Total Integration Score measures the average depth of integration among all services listed. The assigned integration scores are averaged and this score ranges from 0 to 4. In our example the average of all the scores was 1.7. Table 2 shows the score ranges and associated clinical indicators, which range from very low integration (0–0.49) to complete integration (3.5–4). Thus, communities, networks, agencies and individual programs can use the measure to monitor local service integration as a whole, cross-sectoral integration or an individual service's integration with other services. This may also be compared over time or before and after a specific activity.

Table 2.

Indicators for level of service integration scores

| Score range | Clinical indicator |

|---|---|

| 0.0–0.49 | Very little integration |

| 0.5–0.99 | Little integration |

| 1.0–1.49 | Mild integration |

| 1.5–1.99 | Moderate integration |

| 2.0–2.49 | Good integration |

| 2.5–2.99 | Very good integration |

| 3.0–3.49 | Excellent integration |

| 3.5–4.00 | Perfect integration |

Pilot study findings

In our use of the Human Services Measure, we have shown content validity and face validity. Community experts on integration found the measure very helpful. The community leaders also were able to use this measure and valued the information supplied from it. By using the response categories of non awareness to collaboration, they were able to determine which services were collaborating well with each other and which were not. They received a baseline measure so that in the future they can compare their integration longitudinally. Discriminate validity was noted as two different programs, known to be further and less developed in their integration efforts, were scored using this measure and a predicted difference in scores was found. Scores were correlated with the Weiss et al. [20] questionnaire on partnership synergy which representatives of the services also completed. Weak correlations (r=0.13–0.36) were found with the components. Our integrated measure correlated weakly with partnership synergy (r=0.13) but more highly with satisfaction (r=0.36). This was expected as it was thought that these two questionnaires were measuring different components of integration.

Discussion

This paper has offered both a rationale and model of human services integration and illustrates the application of the model using a newly developed instrument for measuring integration with a specific example taken from children's services. Table 3 identifies 2 instruments used for measuring aspects of integration and describes them in relation to their purpose, what is measured, results and what is missed. It looks at the partnership synergy questionnaire by Weiss et al. [20] and the presented Browne et al. Human Services Integration Measure. It appears that each of these models and questionnaires are measuring different components of integration. Thus, neither measure on its own would evaluate the complete nature of functioning and the scope and depth of integration efforts of a program or network. Thus, we recommend the use of both measures.

Table 3.

Comparison of 2 measures of integration

| Dimension | Partnership aynergy (Weiss et al. 2002) | Browne et al. |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To quantify some degree of agencies | To identify the extent, scope (number of |

| working together and what is working or | sectors, agencies) and depth of integration; | |

| wrong (leadership etc.) | and to identify where (between what | |

| services and within what sectors) there is | ||

| depth, scope, and extent of formal and | ||

| informal integration | ||

| What is Measured | Networked members point of view | Network service or program members' |

| point of view regarding the actual depth and | ||

| scope of collaboration | ||

| Results | Single overall and dimension scores | – all services' views of the degree of |

| communication with a single agency | ||

| – a single services' views of the degree of | ||

| communication with all other agencies | ||

| – an overall network score comprised of | ||

| networked services within a sector | ||

| – a measure of the number of sectors | ||

| involved in the network | ||

| What is missed | Where the strengths and problems are | What the strengths and problems are |

| (between sectors and between agencies) | (leadership, involvement, etc.) from a point | |

| involved in a network | of view of the collective network |

Clients' problems are often multiple and complex in many jurisdictions. Coordination and integration of some human services is also a common problem internationally. The range of human services is provided under the auspices of different bureaucracies in different countries, and links among bureaucracies can vary. Nevertheless, the model of integration proposed here can be generalized to other contexts, yet is discussed within a Canadian context.

The integration measure developed from this model assesses local service integration among services sharing minimal links with at least some other local services. It can be used to measure the level of service integration among these programs and services as a whole and can pinpoint which services are collaborating well with each other.

The integration measure does not directly explore levels of funding integration, although the model of integration identifies funding integration as an essential third pillar of human services integration. Thus, questions would need to be added that would probe whether existing funding arrangements were optimizing, facilitating or hindering integrated service delivery.

We hope this approach to conceptualizing and measuring integration will inspire people from other jurisdictions to modify the measure to fit the nature and funding of their services. Such a measure can be used to track integration in a given community before and after receiving interventions aimed to stimulate this kind of collaboration.

Contributor Information

Gina Browne, System Linked Research Unit (SLRU) on Health and Social Service Utilization, School of Nursing, Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, (CE&B) McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Jacqueline Roberts, SLRU, School of Nursing, CE&B, McMaster University, Canada.

Amiram Gafni, SLRU, Centre for Health Economics, Policy Analysis, CE&B, McMaster University, Canada.

June Kertyzia, SLRU, School of Nursing, McMaster University, Canada.

Patricia Loney, SLRU, McMaster University, Canada.

References

- 1.Bauld L, Judge K, Lawson L, Mackenzie M, Mackinnon J, Truman J. Health action zones in transition: progress in. UK: HAZ, Department of Health, Government of the United Kingdom; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Browne G, Gafni A, Byrne C, Roberts J, Majumdar B. Effective/efficient mental health programs for school-age children: a synthesis of reviews. Social Science and Medicine. 2004 Apr;58(7):1367–84. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browne G, Byrne C, Roberts J, Gafni A, Majumdar B, Kertyzia J. System-linked research unit McMaster University 3N46: Report for integrated services for children division. Government of Ontario; 2001. Sewing the seams effective and efficient human services for school-aged children. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browne G, Byrne C, Roberts J, Gafni A, Whittaker S. When the bough breaks: provider-initiated comprehensive care is more effective and less expensive for sole-support parents on social assistance. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;53:1697–710. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson MS. Continuity of care: a re-conceptualization. Medical Care Research Review. 2001;58:255–90. doi: 10.1177/107755870105800301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Easterling D. What have we learned about community partnerships. Medical Care Research and Review. 2003;60(Suppl 4):1615–65. doi: 10.1177/1077558703260221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank RG, Gaynor M. Fiscal decentralization of public mental health care and the Robert Wood Johnson foundation program on chronic mental illness. The Milbank Quarterly. 1994;72(1):81–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haggerty J, Reid R, McGrail K, McKendry R. The University of British Columbia; 2001. Here, there and all over the place: defining and measuring continuity of health care, centre for health services and policy research. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leatt P, Pink GH, Guerriere M. Towards a Canadian model of integrated healthcare. Healthcare Papers. 2000;1:13–35. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..17216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehman AF, Postrado LT, Roth D, McNary SW, Goldman HH. Continuity of care and client outcomes in the Robert Wood Johnson foundation program on chronic mental illness. The Milbank Quarterly. 1994;72(1):105–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payne GT, Blair JD, Fottler MD. The role of paradox in integrated strategy and structure configurations: exploring integrated delivery in health care. Advances in Health Care Management. 2000;1:109–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Provan KG, Milward HB. Do networks really work? A framework for evaluating public-sector organizational networks. Public Administration Review. 2001;61:414–23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan B, Robinson R. Prepared for Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, Government of Ontario; 2002. Evaluation of the healthy babies, healthy children program consolidated report, end of fiscal year 2000–2001. Unpublished document. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schorr L. New York: Double Day; 1988. Within our reach: breaking the cycle of disadvantage. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simoens S, Scott A. Health Economics Research Unit, University of Aberdeen; 1999. Towards a definition and taxonomy of integration in primary care. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Topping S, Calloway M. Does resource scarcity create inter-organizational coordination and formal service linkages? A case study of a rural mental health system. Advances in Health Care Management. 2000;1:393–419. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanderwoerd J. BBBF Research Coordination Unit: Queens University; 1996. Service provider involvement in the onward willow: better beginnings, better futures project 1990–1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volpe R, Batra A, Bomio S. OISE, University of Toronto: 1999. Third generation school-linked services for at risk children. Institute of Child Study. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan TT, Ma A, Lin B. Integration and the performance of healthcare networks: do integration strategies enhance efficiency, profitability, and image? International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2001 Jun 1;:1. doi: 10.5334/ijic.31. Available from: URL: www.ijic.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss E, Anderson R, Lasker R. Findings from the national study of partnership functioning: report to the partnerships that participated. Center for the advancement of collaborative strategies in health. 2001 Available on world wide web, February 2003 at http://www.cacsh.org. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss ES, Anderson RM, Lasker RD. Making the most of collaboration: exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Education and Behavior. 2002;29(6):683–98. doi: 10.1177/109019802237938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods KJ. The development of integrated health care models in Scotland. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2001 Jun 1;:1. doi: 10.5334/ijic.29. Available from: URL: www.ijic.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]