Abstract

A group of plant AtSH3Ps (Arabidopsis thaliana SH3-containing proteins) involved in trafficking of clathrin-coated vesicles was identified from the GenBank database. These proteins contained predicted coiled-coil and Src homology 3 (SH3) domains that are similar to animal and yeast proteins involved in the formation, fission, and uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles. Subcellular fractionation and immunolocalization studies confirmed the presence of AtSH3P1 in the endomembrane system. In particular, AtSH3P1 was localized on or adjacent to the plasma membrane and its associated vesicles, vesicles of the trans-Golgi network, and the partially coated reticulum. At all of these locations, AtSH3P1 colocalized with clathrin. Functionally, in vitro lipid binding assay demonstrated that AtSH3P1 bound to specific lipid groups known to accumulate at invaginated coated pits or coated vesicles. In addition, immunohistochemical studies and actin binding assays indicated that AtSH3P1 also may regulate vesicle trafficking along the actin cytoskeleton. Yeast complementation studies suggested that AtSH3Ps have similar functions to the yeast Rvs167p protein involved in endocytosis and actin arrangement. A novel interaction between AtSH3P1 and an auxilin-like protein was identified by yeast two-hybrid screening, immunolocalization, and an in vitro binding assay. The interaction was mediated through the SH3 domain of AtSH3P1 and a proline-rich domain of auxilin. The auxilin-like protein stimulated the uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles by Hsc70, a reaction that appeared to be inhibited in the presence of AtSH3P1. Hence, AtSH3P1 may perform regulatory and/or scaffolding roles during the transition of fission and the uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles.

INTRODUCTION

Protein–protein interaction domains with highly conserved amino acid sequences form essential components of numerous cellular processes (Pawson, 1995). A well-studied protein–protein interaction domain in animals is the Src homology 3 (SH3) domain. Initially discovered as a noncatalytic domain of the tyrosine kinase Src, SH3 domains are found in a variety of proteins. A typical SH3 domain consists of 50 to 70 amino acids that form two antiparallel β-sheets packed against each other perpendicularly (Musaccho et al., 1994). SH3 domains generally bind to proline-rich domains (PRDs) that adopt a left-handed polyproline II helix conformation with a core PXXP motif (where P is proline and X is any amino acid) (Feng et al., 1994). Like many protein–protein interaction domains, the presence of an SH3 domain in a protein can be determined by sequence comparison (Pawson, 1995).

Functionally, SH3 domains have been demonstrated to play a crucial role in different processes in animals and yeast. As shown in the case of the Src protein kinase family (reviewed by Schwartzberg, 1998) and adaptor proteins such as Grb2 (Lowenstein et al., 1992), SH3 domains are involved in relaying intracellular signals. In yeast, ABP1p (actin binding protein 1) contains an SH3 domain that is responsible for the association with the actin cytoskeleton (Drubin et al., 1990). SH3 domains also play critical roles in the assembly of the active NADPH oxidase enzyme complex in phagocytes (Leto et al., 1990).

Recently, SH3-containing proteins were shown to regulate intracellular trafficking of clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) (Marsh and McMahon, 1999; Brodin et al., 2000). The additional presence of other protein–protein interaction domains, such as the coiled-coil domain responsible for oligomerization (Lupas, 1996), suggests that these SH3-containing accessory proteins provide scaffolding for various components of CCV trafficking. The SH3 domain at the C terminus of amphiphysin interacts with the PRD of the GTPase dynamin that is involved in the fission of the neck of the clathrin-coated pits. This interaction is critical to the recruitment of dynamin to the clathrin-coated pits at the plasma membrane of a synaptic cell (David et al., 1996; Shupliakov et al., 1997). Endophilin, another SH3-containing protein, also interacts with the PRD of dynamin and the phosphoinositide phosphatase synaptojanin (Ringstad et al., 1997). With its intrinsic lysophosphatidic acid acyl transferase (LPAAT) activity, endophilin is involved in the early stages of endocytosis by assisting the generation of negative membrane curvature at the clathrin-coated pits (Schmidt et al., 1999). Syndapin, another dynamin binding protein, also interacts with the neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. It coordinates the actin cytoskeleton with the internalization of the plasma membrane (Qualmann and Kelly, 2000). In addition, several other SH3-containing scaffolding proteins, such as DAP160 (Roos and Kelly, 1998), Ese (Senger et al., 1999), and intersectin (Yamabhai et al., 1998), have been identified, but their specific roles in vesicle trafficking have yet to be determined.

The role of SH3 domains in plants has not received much attention. In fact, no plant SH3 domain has been reported to date. Similarly, although trafficking of CCVs reportedly occurs in plants, detailed molecular studies of the process are only beginning to emerge. The CCV-associated proteins identified, based on sequence homology with animal proteins, include clathrin (Blackbourn and Jackson, 1996), adaptin (Holstein et al., 1994), and dynamin-like proteins (Gu and Verma, 1996; Park et al., 1998). Studies on a putative vacuolar cargo receptor, AtELP (Arabidopsis thaliana epidermal growth factor receptor–like protein), have suggested possible mechanisms for targeting and recycling of CCVs between the trans-Golgi network and the prevacuolar compartment (Sanderfoot et al., 1998). However, protein networks that are involved in the formation or modification of the clathrin coat are not clear. Here we report the identification of several Arabidopsis expressed sequence tags (ESTs) that encode novel SH3-containing proteins known as AtSH3Ps (Arabidopsis thaliana SH3-containing proteins). The association of AtSH3P1 with CCVs of the endomembrane system, an SH3-dependent association of AtSH3P1 with a putative clathrin-uncoating factor, an SH3-independent association with lipids and actin, and the complementation of a yeast endocytosis mutant by AtSH3Ps support the predicted role of AtSH3Ps in clathrin-coated vesicular trafficking.

RESULTS

Cloning of AtSH3Ps

Three Arabidopsis ESTs coding for SH3-containing proteins were identified using the SH3 domain of the human p67phox as the BLAST query. Sequencing revealed that each EST contained a substantial untranslated region 5′ to the coding region without any long open reading frame. The 3′ untranslated region of each EST contained a poly(A) tail. The corresponding genomic sequence in the GenBank database also suggested the same open reading frames. Hence, we concluded that each of the three ESTs contained a full-length coding sequence and named the encoded proteins AtSH3Ps. It should be noted that at least one more SH3-containing protein similar to AtSH3Ps was predicted from its genomic DNA sequence (data not shown).

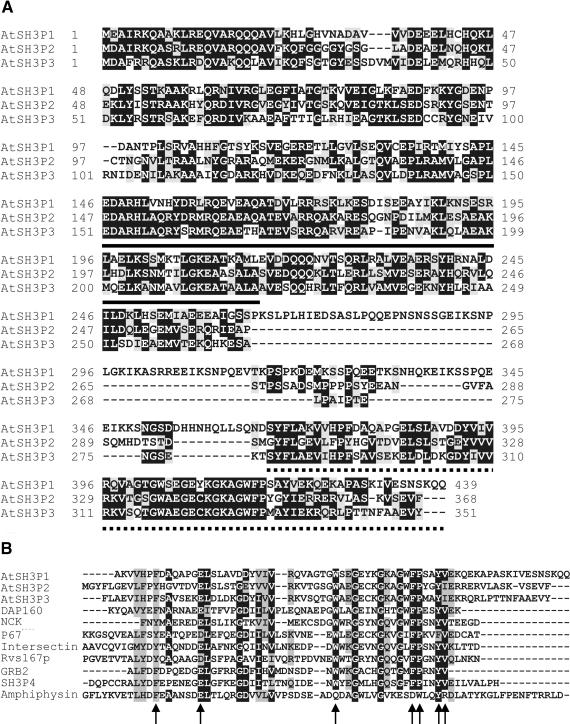

AtSH3P1, AtSH3P2, and AtSH3P3 contain 439, 368, and 351 amino acids, respectively (Figure 1A) and share 43 to 52% amino acid identity. The three proteins do not contain regions predicted to form a transmembrane domain. Using SMART (Schultz et al., 1998), it was predicted that each AtSH3P contained an SH3 domain at the C terminus and a coiled-coil domain at the N terminus (Figure 1A). In fact, these two domains form the main blocks of conserved residues among AtSH3Ps that are linked by a highly divergent middle segment. Interestingly, the domain arrangement of AtSH3Ps is similar to that of the endophilin family (Ringstad et al., 1997). Another survey using Paircoil (Berger et al., 1995) revealed that the presence of an N-terminal coiled-coil domain and a C-terminal SH3 domain was consistent among all SH3-containing proteins involved in animal or yeast clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

Figure 1.

AtSH3P Is a Novel Plant Protein Family Containing a Predicted Coiled Coil and an SH3 Domain.

(A) Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of AtSH3P1, AtSH3P2, and AtSH3P3. Black boxes represent identical residues, and gray boxes represent conserved residues. The predicted coiled-coil domain (solid) and SH3 domain (dotted) are underlined.

(B) Alignment of the predicted SH3 domain with known animal SH3 domains. Black and gray boxes represent identical residues and conserved residues, respectively. Amino acids critical to ligand binding are indicated by arrows.

BLAST searches of GenBank suggested that AtSH3Ps were novel proteins. AtSH3P1 exhibited greatest similarity to Ese (Senger et al., 1999) and intersectin (Yamabhai et al., 1998). AtSH3P2 showed highest homology with the dynamin-associated protein Dap160 (Roos and Kelly, 1998). AtSH3P3 was most related to Dap160, intersectin, and Ese. The region of homology of each AtSH3P with known proteins was limited only to the SH3 domain (Figure 1B). In particular, residues that are critical to ligand binding in animal or yeast SH3 domains also were present in the SH3 domain of each AtSH3P (Mayer and Eck, 1995). The predicted coiled-coil domain of AtSH3Ps did not have high homology with those of any known proteins.

Expression of AtSH3Ps

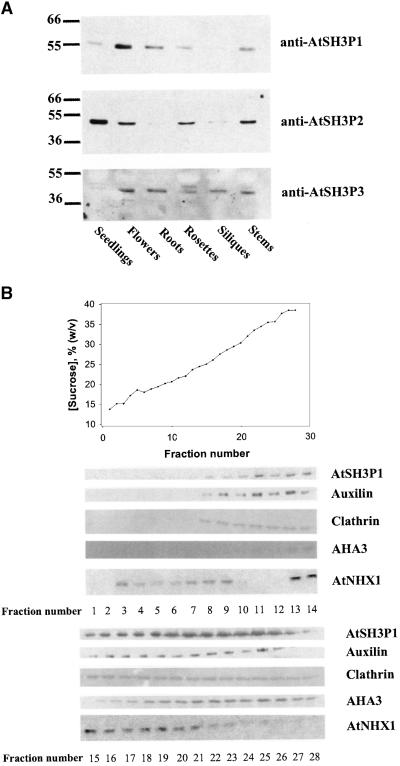

Protein gel blot analysis using antibodies raised against the AtSH3Ps suggested that each AtSH3P had a unique tissue expression pattern (Figure 2A). AtSH3P1, a 57-kD protein, was very abundant in flowers. It also was detected in seedlings, roots, leaves, and stems. The expression of the 50-kD AtSH3P2 was high in seedlings and intermediate in flowers, leaves, and stems. The 46-kD AtSH3P3 was detected in all tissues tested except seedlings.

Figure 2.

Tissue and Subcellular Expression of AtSH3Ps.

(A) Twenty micrograms of total protein extracts from 7-day-old seedlings, flowers, leaves, roots, siliques, and stems of Arabidopsis were resolved on SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-AtSH3Ps. The results are representative of four independent experiments.

(B) One-tenth of 1-mL fractions of a continuous sucrose density gradient of Arabidopsis were resolved on SDS-PAGE and probed with antibodies raised against AtSH3P1, auxilin-like protein, plant clathrin, Arabidopsis plasma membrane H+-ATPase (AHA3), and Arabidopsis vacuolar Na+/H+-antiport (AtNHX1). The corresponding sucrose concentration of each fraction is presented in the graph at top.

Subcellular fractionation indicated that AtSH3P1 associated with the endomembrane system (Figure 2B). AtSH3P1 was detected in fractions of a continuous sucrose gradient with sucrose concentrations of 20 to 35%. Clathrin, a coat protein of the endomembranes, also was present in the same fractions. Similar distribution was observed for AtSH3P2 and AtSH3P3 (data not shown).

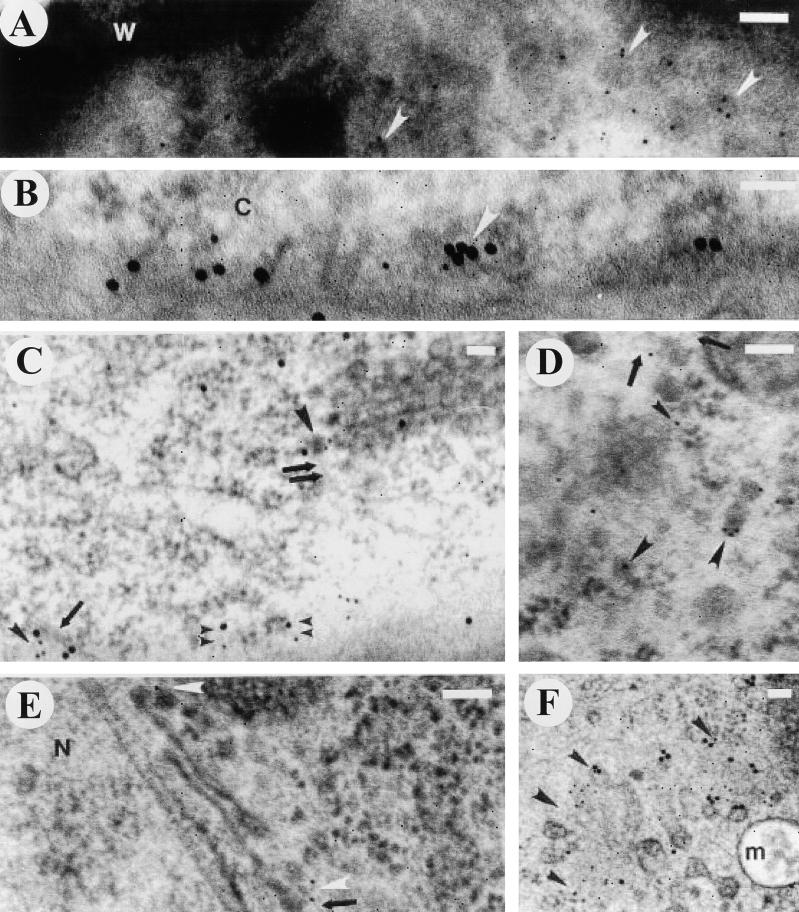

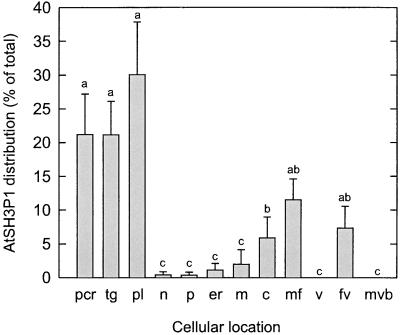

Immunocytochemical studies demonstrated that the AtSH3P1 protein localized to the plasma membrane and associated CCVs (Figures 3A to 3C), trans-Golgi network and associated CCVs (Figures 3C to 3E), partially coated reticulum (Figure 3F), and free vesicles and microfilaments (Figures 3C to 3E) of the vegetative and generative cell of the Arabidopsis pollen grain. Immunolocalization of AtSH3P1 to these cellular compartments was significantly greater than to other regions of the cell (Figure 4). Colocalization of AtSH3P1 and clathrin was present at the plasma membrane (Figures 3B and 3C), the trans-Golgi network (Figure 3C), and the partially coated reticulum (Figures 3D and 3F). A pairwise multiple comparison procedure (Dunn's method; P < 0.001) indicated that there were no significant differences between the distribution of AtSH3P1 and clathrin at all locations.

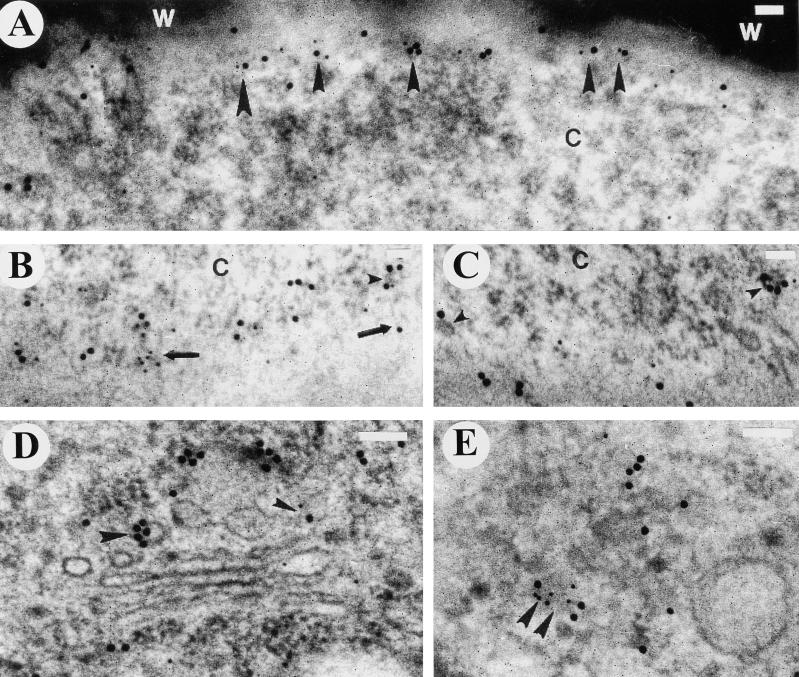

Figure 3.

Electron Micrographs of Immunolocalization of AtSH3P1 and/or Clathrin in Pollen Grains of Arabidopsis.

(A) Glancing section adjacent to the plasma membrane of the vegetative cell. AtSH3P1 localized to vesicles with structural characteristics of clathrin coats. Arrowheads denote some of the vesicles.

(B) Colocalization of AtSH3P1 and clathrin. Glancing section adjacent to the plasma membrane. Arrowhead denotes colocalization on a budding vesicle.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Gold Particles after Immunolocalization of AtSH3P1 in Developing Pollen Grains of Arabidopsis.

Bars labeled with the same letter were not significantly different from one another as determined using analysis of variance on ranks and Dunn's multiple comparisons procedure. pcr, partially coated reticulum; tg, trans-Golgi network; pl, plasma membrane; n, nucleus; p, plastid; er, endoplasmic reticulum; m, mitochondria; c, cytoplasm; mf, microfilaments; v, vacuole/tonoplast; fv, free vesicles; mvb, multivesicular body. Error bars represent 95% confidence levels.

(C) Colocalization of AtSH3P1 and clathrin adjacent to the plasma membrane (double arrowheads) and on a vesicle (large arrowhead) associated with a microfilament (double arrows) at the trans-Golgi network. AtSH3P1 and clathrin colocalize with a microfilament (small single arrowhead) bridging a microtubule (arrow) adjacent to the plasma membrane.

(D) and (E) Localization of AtSH3P1 to the trans-Golgi network (arrowheads). Arrows denote microfilaments associated with vesicles.

(F) Overview of localization of AtSH3P1 and clathrin to the partially coated reticulum. Arrowheads indicate the boundary of the partially coated reticulum. Colocalization can be seen at the upper two arrowheads.

For AtSH3P1, 10-nm gold particles were used; for clathrin, 18-nm gold particles were used. C, cytoplasm; m, multivesicular body; N, nucleus; W, pollen wall. Bars = 100 nm.

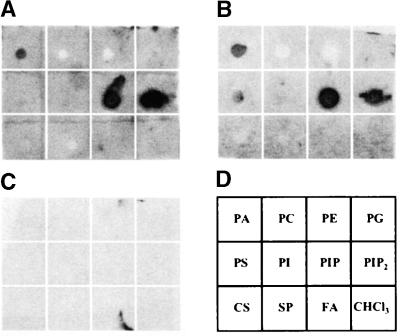

AtSH3P1 Binds Specific Headgroups of Phospholipids

Because AtSH3P1 is associated with endomembranes and several animal CCV-associated accessory proteins have shown lipid binding/modifying ability, we used in vitro lipid binding assay to determine whether AtSH3P1 is a lipid binding protein (Figure 5). AtSH3P1 bound strongly to phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate, and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. The binding was mediated mainly through the headgroups, because AtSH3P1 did not interact with fatty acid CoA. Moreover, the binding to each lipid was not dependent on the presence of the SH3 domain.

Figure 5.

AtSH3P1 Binds to Specific Lipid Types.

Five micrograms of lipids was spotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and subjected to in vitro lipid binding assay as described in Methods using full-length AtSH3P1 (A), AtSH3P1 without the SH3 domain (B), and GST-SH3 domain as probes (C). The lipids used were phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PIP), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), cholesterol (CS), sphingomyelin (SP), and fatty acid CoA (FA). Chloroform (CHCl3), the solvent for the lipids, also was spotted as a negative control. The relative position of each sample on the blots is indicated in (D).

AtSH3P1 Binds Actin in Vitro

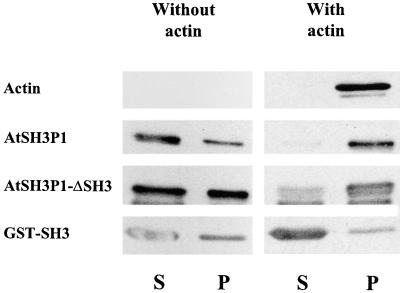

High speed cosedimentation studies suggested that AtSH3P1 binds to actin in vitro (Figure 6), thus providing support to our immunohistochemical observations of the association of AtSH3P1 with the cytoskeletal network. Both full-length AtSH3P1 and AtSH3P1 lacking the SH3 domain copelleted with actin (Figure 6). The SH3 domain alone did not bind to actin, suggesting that the actin binding domain of AtSH3P1 was distinct from the SH3 domain.

Figure 6.

AtSH3P1 Binds Actin at a Region Distinct from the SH3 Domain.

Recombinant proteins of AtSH3P1, AtSH3P1 without the SH3 domain (AtSH3P1-ΔSH3), and the GST-SH3 domain fusion were incubated with (right) or without (left) F-actin and centrifuged at 280,000g. The presence of AtSH3P1 or actin in either the supernatant (S) or the pellet (P) was determined by anti-AtSH3P1 or anti-actin protein gel blotting.

AtSH3Ps Partially Complement the Function of a Yeast Endocytosis-Related Protein

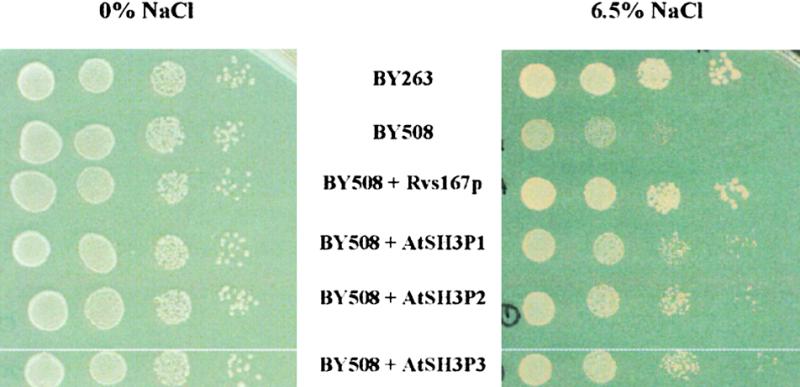

In yeast, RVS167 encodes the RVS167p protein containing a similar domain arrangement to AtSH3Ps. RVS167p associates with protein networks that regulate the actin cytoskeleton and vesicle trafficking (Colwill et al., 1999). Deletion of RVS167 results in salt sensitivity and defects in endocytosis (Colwill et al., 1999). Complementation experiments were performed to determine whether AtSH3Ps have cellular function(s) similar to RVS167p. Yeast strain BY508 lacking RVS167p grew poorly on 6.5% NaCl (Figure 7). Expression of RVS167p in BY508 allowed the growth of yeast on salt at a level similar to that in BY263 (wild type). The heterologous expression of each of the AtSH3Ps in BY508 also improved the viability of BY508 on 6.5% NaCl (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

AtSH3Ps Partially Complement a Salt-Sensitive, Endocytosis-Deficient Yeast rvs167 Mutant.

Serially diluted late log-phase cultures were spotted onto minimal medium supplemented with 0 or 6.5% (w/v) NaCl. The results shown are representative of four independent experiments.

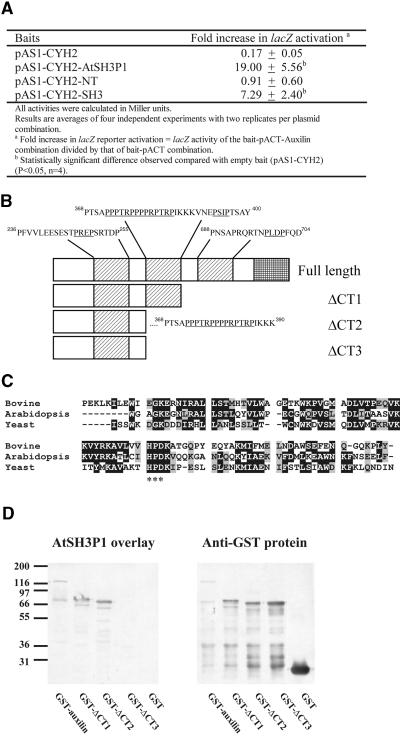

AtSH3P1 Binds Vesicle-Trafficking Proteins

To identify the possible interacting partner(s) of AtSH3Ps, the predicted SH3 domain of AtSH3P1 was used for yeast two-hybrid screening of an Arabidopsis cDNA library. Five distinct cDNAs were isolated. Sequencing revealed that each cDNA coded for a protein containing at least one PRD with a PXXP motif (Table 1). One of the five clones identified encoded a protein with similarity to animal auxilin that is involved in the uncoating stage of clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Jiang et al., 1997). Cotransformation of Y190 with different pAS1-CYH2 constructs of AtSH3P1 and the original pACT-auxilin construct obtained from the screen showed that the interaction required the presence of the SH3 domain of AtSH3P1 (Figure 8A).

Table 1.

Putative Interactors of the SH3 Domain of AtSH3P1

| Putative Interactor | PXXP Motif? |

Function in Vesicle Trafficking? |

Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extensin-like protein | Yes | No | T06291 |

| Auxilin-like protein | Yes | Yes | T06636 |

| Cyclin G–dependent kinase-like protein |

Yes | Yes | T01122 |

| Putative pollen-specific protein |

Yes | N/A | BAB08664 |

| Unknown | Yes | N/A | BAB08592 |

N/A, not applicable.

Figure 8.

Interaction between AtSH3P1 and Auxilin-Like Protein Is Mediated through the AtSH3P1 SH3 Domain and the PRD of Auxilin-Like Protein.

(A) SH3-dependent interaction of AtSH3P1 and auxilin-like protein in a yeast two-hybrid system.

(B) Domain organization of auxilin-like protein. Predicted PRDs and the DnaJ domain are represented by shaded and cross-hatched boxes, respectively. The possible SH3 binding PXXP motifs are underlined.

(C) Alignment of the amino acid sequence of the DnaJ domain of auxilin-like protein with that of bovine auxilin (accession number Q27974) and yeast Swa2p (accession number NP010606). The HPD motif, responsible for stimulating Hsp70 ATPase activity, is indicated by asterisks.

(D) AtSH3P1 overlay (left) on bacterial extracts with GST fusion of full-length or truncated forms of the auxilin-like protein described in (B). The presence of each GST fusion protein was confirmed by anti-GST protein gel blotting (right).

The predicted protein sequence of the full-length auxilin-like protein (924 amino acids) was obtained from GenBank (Table 1). It consists of three putative SH3 binding PRDs and a C-terminal DnaJ domain (Figure 8B). Sequence alignment suggested that the DnaJ domain was similar only to those from the auxilin protein family (Figure 8C). Significantly, the plant DnaJ domain contained the HPD motif that was known to be crucial in stimulating the heat shock protein Hsc70 (Tsai and Douglas, 1996). Unlike the animal auxilin, but like the yeast Swa2p auxilin-like protein (Gall et al., 2000), no tensin-like or clathrin binding domain was predicted in the amino acid sequence. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions of the full-length auxilin-like protein and truncated proteins lacking either one or two of the PRDs were generated. Overlay assays showed that AtSH3P1 bound preferentially to the PRD2 of auxilin-like protein (Figure 8D). In particular, the core sequence 368PTSAPPPTRPPPPRPTRPIKKK389, containing the PXXP motif, appeared critical for AtSH3P1 binding (Figure 8D).

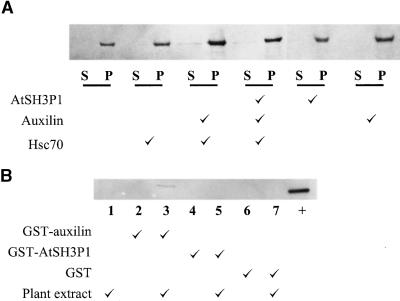

To demonstrate that the auxilin-like protein interacting with AtSH3P1 is in fact a clathrin-uncoating factor, two experiments were performed: (1) GST pulldown assays demonstrated that the auxilin-like protein bound to clathrin from a plant extract (Figure 9A); and (2) GST-auxilin–like protein increased the uncoating of clathrin from plant microsomal membranes by animal Hsc70 in vitro (Figure 9B). The presence of AtSH3P1 slightly inhibited the uncoating activity of the auxilin/Hsc70 complex (Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

The AtSH3P1-Associating Auxilin-Like Protein Binds and Uncoats Clathrin.

(A) Clathrin uncoating. Arabidopsis microsomal membrane was incubated with AtSH3P1, auxilin-like protein, animal Hsc70, or combinations of these proteins. The supernatant (S) or pellet (P) of a 100,000g centrifugation of the treated membrane was collected and subjected to protein gel blotting for the presence of clathrin (as shown at top) and each GST fusion protein (data not shown).

(B) GST pulldown binding assay. Glutathione resins with no recombinant protein (lane 1), with GST-auxilin (lanes 2 and 3), GST-AtSH3P1 (lanes 4 and 5), and GST (lanes 6 and 7) were incubated with binding buffer (even-numbered lanes) or Arabidopsis cytosol (odd-numbered lanes) as described in Methods. The presence of “pulled down” clathrin was determined by protein gel blotting using the anti-plant clathrin antibodies. Ten micrograms of Arabidopsis cytosol was loaded in lane 8 as a positive control for the immunoblotting.

A pairwise multiple comparison procedure (Dunn's method; P < 0.001) indicated that there were no significant differences between the distribution of AtSH3P1 and the auxilin-like protein at all locations within the vegetative and generative cells of the developing pollen grains. The auxilin-like protein was associated with the plasma membrane (Figures 10A to 10C), apparent free vesicles (Figures 10B and 10C), trans-Golgi network (Figure 10D), and partially coated reticulum (Figure 10E). Colocalization with AtSH3P1 was present at each location (Figures 10A to 10E).

Figure 10.

Electron Micrographs of Colocalization of AtSH3P1 and the Auxilin-Like Protein to Arabidopsis Pollen Grains.

(A) to (C) Glancing section of the plasma membrane illustrating distribution on or adjacent to the plasma membrane.

(A) Arrowheads denote localization events. The middle arrowhead represents colocalization on the face of a budding CCV.

(B) and (C) Arrowheads denote localization on vesicles. Arrows indicate microfilaments.

(D) Arrowheads denote localization at the trans-Golgi network.

(E) Double arrowheads denote colocalization on the face of partially coated reticulum.

For AtSH3P1, 10-nm gold particles were used; for auxilin-like protein, 18-nm gold particles were used. C, cytoplasm; W, pollen wall. Bars = 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

This study provides the identification of a novel plant SH3 domain–containing protein family (AtSH3Ps). Our results suggested that AtSH3Ps likely are involved in trafficking and modification of CCVs, a process that is poorly characterized in plants. Significantly, AtSH3Ps have domain arrangements similar to several accessory proteins involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis in animals and yeast. Immunolocalization studies indicated the presence of AtSH3P1 at CCVs of the endomembrane system and associated microfilaments. In addition, sucrose gradient fractionation suggested the comigration of AtSH3Ps and clathrin. These findings were supported by in vitro binding assays demonstrating that AtSH3P1 interacted with lipids and actin directly. Complementation of the yeast rvs167 mutation suggested a functional role of AtSH3Ps in vesicle trafficking and actin organization in vivo. Finally, AtSH3P1 formed a complex, in an SH3-PRD–dependent manner, with a protein exhibiting sequence similarity and similar function to auxilin, a clathrin-uncoating factor in animals and yeast.

Sequence data indicated that AtSH3Ps are structurally similar to the major accessory proteins involved in each of the steps of CCV processing in animals and yeast. Specifically, the AtSH3Ps share similar N-terminal coiled-coil and C-terminal SH3 domain arrangements with the endophilin family as well as amphiphysin, Ese, intersectin, and syndapin. Except for endophilin, which exhibits lipid-modifying ability (Schmidt et al., 1999), none of the SH3-containing accessory proteins has an identified associated enzymatic activity. Instead, the accessory proteins act as scaffolding through their multiple interaction domains, thereby optimizing the spatial distribution of the factors involved in coat formation, fission, and uncoating. The SH3 domains of all the aforementioned accessory proteins interact with the PRD of the GTPase dynamin (Brodin et al., 2000). Amphiphysin and endophilin also interact with the PRD of synaptojanin, an inositol 5-phosphatase, via their SH3 domains (Ringstad et al., 1997; Wigge and McMahon, 1998). The coiled-coil domains provide rigid structural support for the highly organized clathrin cage in addition to permitting oligomerization within and between the accessory proteins (Lupas, 1996). Additionally, protein–lipid interaction domains are present in the region of the mammalian/yeast scaffolding proteins distinct from the SH3 domain and include the adaptin binding and clathrin binding regions of amphiphysin (Marsh and McMahon, 1999), the LPAAT of endophilin (Schmidt et al., 1999), and the epsin homology domain of Ese for interaction with epsin (Senger et al., 1999). Notably, our sequence-based data search did not reveal any additional known protein–lipid interaction domains of AtSH3Ps, as observed in other systems. However, unlike the SH3 domains, some of the protein–lipid interaction domains of endocytosis-related proteins are not highly conserved. In vitro binding assays in this study suggested actin and lipid binding ability in the non-SH3 coding region of AtSH3P1. Further mapping will help to identify the exact coding sequence for novel actin/lipid interaction domains in plant proteins.

Although there are a large number of animal or yeast SH3-containing proteins participating in diverse cellular processes, we were able to identify only a few plant SH3-containing proteins by sequence-based search of the completed Arabidopsis genome. Interestingly, we did not find an Arabidopsis protein that resembles any animal protein of the SH3-mediated signaling pathways. The SH3 domain of AtSH3P1 was related to various animal SH3 domains, but it had a binding preference most similar to animal amphiphysin and endophilin. The mapping of the interacting region between the SH3 domain of AtSH3P1 and the auxilin-like protein suggests that the stretch of amino acids 368PTSAPPPTRPPPPRPTRPIKKK389 of the PRD2 of the auxilin-like protein could be a putative plant SH3 binding motif. Significantly, the core sequence of 374PTRPPPPRPTR384 matches both class I (RXXPXXP, where R is arginine) and class II (PXXPXR) SH3 binding motifs (Mayer and Eck, 1995). As determined in the interaction between amphiphysin or endophilin and synaptojanin, amphiphysin bound to a consensus PXRPXR motif, whereas endophilin preferred PXRPXR or PXRPPXPR (Cestra et al., 1999). Additional experiments to determine which arginine(s) in 374PTRPPPPRPTR385 is a critical residue for interaction will help to indicate if the PRD of the auxilin-like protein fits into the AtSH3P1 SH3 domain in an amphiphysin- or endophilin-like fashion.

AtSH3P1 bound specifically to phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate, and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. It did not have affinity with phosphatidylcholine or phosphatidylethanolamine, which are the main glycerolipids found in plant endomembranes (Moreau et al., 1998). The affinity of AtSH3P1 for specific lipids may have functional implications. Phosphatidic acid is classified as a cone-shaped lipid that promotes negative membrane curvature. A lipid monolayer containing phosphatidic acid has the headgroups more clustered together, whereas the acyl chains are loose and diverged. This results in severe membrane bending, which frequently is observed at the deeply invaginated coated pits (Huttner and Schmidt, 2000). Interestingly, endophilin, as an LPAAT, is believed to promote membrane bending at the site of vesicle formation by converting lysophosphatidic acid to phosphatidic acid (Schmidt et al., 1999). Although AtSH3P1 has not been shown to have LPAAT activity, its association with phosphatidic acid may allow a targeted localization to the site of invagination. Subsequently, other binding domains of AtSH3P1 may recruit different components of vesicle trafficking to the invaginated pits. On the other hand, the accumulation of phosphoinositides is known to maintain the stability of coat proteins around the vesicles (Martin, 1998). Likewise, these lipids act as secondary messengers in signal transduction pathways. Hence, the fluctuation of phosphoinositides may regulate the association of AtSH3P1 with vesicles as well as with the components involved in trafficking.

Observations from the present study argue for a role of AtSH3P1 not only in scaffolding via binding of the auxilin-like protein and lipids but also in CCV trafficking via interactions with actin filaments. AtSH3P1 localized to actin filaments and vesicles associated with the cytoskeleton. Cosedimentation studies showed that a region distinct from the SH3 domain of AtSH3P1 was involved in actin binding. Likewise, AtSH3P1 rescued the rvs167 yeast mutant deficient in endocytosis and actin distribution. RVS167p was shown to interact with actin filaments via the actin binding protein ABP1p (Lila and Drubin, 1997). Additionally, the SH3 domain of Rvs167p interacts with Pan1p, a yeast homolog of the animal eps15 protein (Wendland and Emr, 1998). Pan1p also was shown to associate with yAP180p, the yeast AP180 clathrin minor assembly protein (Wendland and Emr, 1998). The interaction of CCV accessory proteins with actin filaments is not unique to Arabidopsis or yeast because syndapin has been demonstrated to interact with the actin network in animal systems (Qualmann and Kelly, 2000). Although both Rvs167p and syndapin regulate actin dynamics via interactions with actin-regulatory protein complexes, our cosedimentation experiments suggested that AtSH3P1 binds to actin directly. The affinity of AtSH3P1 to secondary messengers such as phosphoinositides also suggested that the level of these lipids may alter the association of AtSH3P1 with actin, as observed in several animal cytoskeletal proteins (Martin, 1998), and subsequently could regulate vesicle trafficking along the cytoskeleton.

Animal auxilin was identified originally as a minor clathrin assembly protein in neuronal cells (Ahle and Ungewickell, 1990), and recent studies indicated that it is involved in uncoating CCVs through its interaction with the Hsc70 chaperone (Jiang et al., 1997). In addition to an N-terminal tensin-like domain and a clathrin binding region, the animal auxilin contains one PRD and a C-terminal DnaJ domain, as does the Arabidopsis auxilin-like protein (Figure 7B). The interaction of the DnaJ domain with Hsc70 induces the polymerization of Hsc70, leading to the binding of Hsc70 to clathrin after fission (Jiang et al., 1997). Although the Arabidopsis auxilin-like protein does not contain a region similar to the clathrin binding domain of animal auxilin, GST pulldown assays suggested that it could interact directly with clathrin (Figure 9A). Likewise, the Arabidopsis auxilin-like protein induced clathrin uncoating from vesicles in the presence of Hsc70 (Figure 9B). AtSH3P1, an interacting partner of the auxilin-like protein, reduced the uncoating activity of the auxilin/Hsc70 complex, suggesting that AtSH3P1 may provide, in addition to scaffolding, regulation of clathrin uncoating. This parallels the recruitment of synaptojanin to membrane by endophilin in animals. Abortion of the SH3-dependent interaction between synaptojanin and endophilin resulted in increased free CCVs (Gad et al., 2000). It was hypothesized that the presence of synaptojanin was critical for the dephosphorylation of membrane lipids, which subsequently could weaken the association of coat proteins and the membrane (Gad et al., 2000). Hence, AtSH3P1 and endophilin may act as molecular switches that provide both spatial and temporal coordination for the transition from fission to uncoating of CCVs.

Although observations on CCV trafficking have been reported in plants (Battey et al., 1999), our understanding of the process at the molecular, cellular, and developmental levels still is limited. At the molecular level, CCV trafficking involves the formation and targeting of the cargo vesicles. Studies on the putative vacuolar sorting receptor AtELP and its associated proteins have provided models for how CCVs could be targeted or recycled between the trans-Golgi network and the prevacuolar compartments (Sanderfoot et al., 1998). However, little is known about the molecular basis of CCV trafficking between the plasma membrane and the trans-Golgi/partially coated reticulum networks. Moreover, in both of these pathways, it is unclear how CCVs are formed and modified. Despite the fact that more than 20 accessory proteins responsible for clathrin coat assembly or disassembly have been identified and characterized in animals and yeast, only a handful of plant accessory proteins have been identified so far. Although the basic protein components of the clathrin coat are similar to those of other organisms, the plant accessory proteins that have been identified so far have shown some differences. For example, among the few dynamin-like proteins identified, none contained an SH3-interacting PRD. Moreover, the Arabidopsis dynamin-like proteins were localized to different organelles, such as plastids (Park et al., 1998), and have yet to be shown to associate with CCV trafficking. In the present study, sequence-based searching led to the identification of AtSH3P1, which resembled proteins such as amphiphysin or endophilin structurally, although they have low sequence similarity. AtSH3P1 interacted with actin and lipids via a region with no homology with any protein. These results would imply that plant actin/lipid binding domains, and possibly other functional domains active in vesicle trafficking, are distinct from those of other organisms. In addition, AtSH3P1 also interacted with auxilin, a clathrin-uncoating factor. This interaction has not been reported in other organisms, suggesting that plants may have a different molecular network for CCV processing. The identification of interacting partners of other AtSH3Ps is in progress. This will provide new insights into SH3/clathrin-mediated vesicle trafficking in planta.

Our immunolocalization observations provide novel ultrastructural evidence indicating that CCVs and accessory proteins involved in CCV modification are present at various sites within the developing haploid pollen grain of Arabidopsis. AtSH3P1 colocalized with clathrin and an auxilin-like protein at the plasma membrane, trans-Golgi network, and partially coated reticulum of pollen grains. Previous studies in various plant taxa also suggested the presence of CCVs in developing pollens and pollen tubes (Nakamura and Miki-Hirosige, 1982; Blackbourn and Jackson, 1996; Battey et al., 1999). It was hypothesized that CCV trafficking contributes to membrane recycling during cell plate formation and pollen tube growth. Our data indicated that each AtSH3P also was expressed in other plant tissues, confirming a potential role for these proteins in CCV formation throughout the plant. Further molecular analysis may clarify the role of clathrin-mediated vesicle trafficking in pollen development as well as other possible roles of CCVs in cell plate formation, membrane recovery, and internalization of receptor-ligand complexes in plants (Battey et al., 1999).

METHODS

Cloning of AtSH3Ps

An in silico approach (identified from the GenBank database) was used to identify Src homology 3 (SH3) domain–containing proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. The amino acid sequences of known animal SH3 domains were used as inputs in a BLAST search for Arabidopsis expressed sequence tags (ESTs) or genomic DNA that predicted SH3-containing proteins. Three ESTs (see Table 1 for accession numbers) coding for putative SH3-containing proteins were identified using the SH3 domain of the human NADPH oxidase subunit p67phox (Leto et al., 1990; GenBank accession number P19878). These ESTs were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Columbus, OH) and sequenced.

Plant Material

Arabidopsis (ecotype Columbia-0) was grown at 22°C with 80% RH and a 12-hr-light/12-hr-dark cycle in an environmentally controlled growth chamber.

Production of Recombinant Protein and Polyclonal Anti-AtSH3P Antibodies

The coding sequences for AtSH3P1 (including full-length, full-length minus SH3 domain, and SH3 domain alone) and AtSH3P2/3 were cloned in frame with glutathione S-transferase (GST) into pGEX2TK and pGEX5X1 (Pharmacia), respectively. The recombinant AtSH3Ps were purified as described elsewhere (Aharon et al., 1998). The coding sequences of the full-length and various truncated forms of the auxilin-like protein obtained in the yeast two-hybrid screen were cloned in frame with GST into pGEX2TK. Total bacterial extracts containing the various GST-auxilin fusion proteins were used for the overlay assays (see below). Polyclonal antibodies raised against each AtSH3P were prepared from New Zealand White rabbits injected with the purified recombinant proteins. Polyclonal antibodies raised against the auxilin-like protein were prepared from Wistar rats injected with the purified full-length GST fusion protein. Antibodies were affinity purified using immunoblots as described previously (Harlow and Lane, 1988).

Membrane and Cytosol Isolation

Ten grams of aboveground tissues of seedlings and mature Arabidopsis were ground in 100 mL of 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 250 mM mannitol, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 5% (w/v) insoluble polyvinylpyrrolidone in the presence of quartz sand using a pestle and mortar. The homogenate was centrifuged at 8000g for 20 min in a Sorvall (Newtown, CT) SA 600 rotor. The supernatant then was centrifuged at 100,000g for 45 min in a Beckman Ti45 rotor. The resulting supernatant (cytosol) was concentrated 10 times using an Amicon (Beverly, MA) stirred cells concentrator with a 3-kD molecular mass cutoff filter. The pellets (microsomal membranes) were resuspended in storage buffer (6 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10% [w/v] glycerol, 250 mM mannitol, 2 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF) at ∼4 mg/mL. Three milliliters of the membranes then were layered on top of a 30-mL continuous sucrose density gradient (10 to 40% [w/v]) and centrifuged in a Beckman SW27 rotor at 70,000g for 2 hr at 4°C. One-milliliter membrane fractions were collected. The sucrose concentration of each membrane fraction was determined using a refractometer. The fractions were diluted three times with storage buffer, centrifuged at 100,000g for 40 min in a Beckman TLA100.4 rotor, and resuspended in 100 μL of storage buffer.

Protein Gel Blots and AtSH3P1 Overlays

Extracts were obtained by grinding tissue to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and solubilization in Laemmli's sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970). Total bacterial and yeast extracts were obtained from cells of a log-phase culture. Protein samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. For protein gel immunoblotting, blots were incubated with 1:1000 dilutions of anti-AtSH3P antibodies for 2 hr at 25°C. For AtSH3P1 overlays, blots were first incubated with 10 μg/mL recombinant AtSH3P1 for 3 hr at 25°C and then with 1:1000 dilutions of anti-AtSH3P1 antibodies for 1 hr at 25°C. Blots were visualized by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies for 1 hr at 25°C followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Sigma).

Electron Microscopy and Immunolocalization

Anthers of Arabidopsis containing pollen in the bicellular stage of development were cryofixed as described by Hawes (1994). Liquid propane cooled with liquid nitrogen was used for rapid freeze fixation of anthers. Freeze substitution was completed over 11 days in anhydrous acetone containing 2% osmium tetroxide with or without 2% uranyl acetate as a substitution medium. Subsequently, anthers were brought to room temperature, embedded in Spurr's resin (Spurr, 1969), divided into 70-nm sections, and collected on formvar-coated nickel grids. Sections were blocked and incubated with anti-AtSH3P1 antibodies and/or anti-clathrin– or anti-auxilin–like protein antibodies at room temperature for 5 or 18 hr for single and double antigen localizations, respectively. The blocking solution was 4% BSA in PBS, and incubation solutions contained PBS plus primary and/or secondary antibodies. AtSH3P1 antibody dilutions were 1:50 for single localization and 1:10 for colocalization. Increased concentrations were used for colocalization because AtSH3P1 binding was reduced. Dilutions for the auxilin-like protein and clathrin were 1:50 for all localizations. The specificity of the antibody distribution in the developing pollen grains was assessed by first counting the number of localization events in 9-μm2 randomly selected regions in 10 pollen grains from each of seven separate flowers for a total of 70 pollen grains. Distribution within the cell was compared using analysis of variance on ranks and Dunn's method (P < 0.001) of pairwise multiple comparison (Sigma Stat 2.03). Qualitative observations of immunolocalization events were made on three to five serial sections of more than 600 pollen grains from seven separate flowers.

In Vitro Lipid Binding

The affinity of AtSH3P1 for different lipids was determined as described previously (Stevenson et al., 1998). Five micrograms of lipids (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) was spotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and allowed to air dry for 1 hr at 25°C. The blots then were blocked in 3% (w/v) fatty acid–free BSA (ICN, Costa Mesa, CA) in PBST (PBS with 0.1% [v/v] Tween 20) for 2 hr at 25°C, followed by incubation with recombinant AtSH3P1 proteins (5 μg/mL in PBST) overnight at 4°C. The membranes then were incubated with 1:1000 dilutions of anti-AtSH3P1 antibodies for 1 hr at 25°C. Binding of AtSH3P1 to lipids was visualized by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies for 1 hr at 25°C followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Sigma).

Actin Cosedimentation

The entire procedure was performed as described (Yokota et al., 1998) at 25°C with slight adjustments. Actin from chicken muscle (Sigma) was allowed to polymerize in polymerization buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM EGTA, 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 150 mM KCl) for 1 hr. Twenty-five micromolar of polymerized actin was incubated with 1 μg of recombinant AtSH3P1 in a 25-μL reaction mixture of polymerization buffer with 1 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM KCl for 1 hr. The reactions were centrifuged in a Beckman TLA100 rotor at 280,000g for 25 min. The supernatant and pellets were collected and subjected to protein gel blotting using anti-AtSH3P1 or anti-actin (ICN) antibodies.

Yeast Complementation

The complete coding sequences of AtSH3P1, AtSH3P2, and AtSH3P3 were cloned into p413MET25 under the control of the MET25 promoter (Ronicke et al., 1997) and transformed into yeast strain BY508 (with a deletion of the RVS167 gene). Both BY508 and BY263 (wild type) also were transformed with the empty p413MET25 as control. The expression of each AtSH3P in BY508 was verified using protein gel blotting as described above (data not shown).

For yeast complementation, transformed yeast cells were grown to late log phase. Then, cultures were diluted serially and spotted onto assay plates supplemented with minimal medium containing 2% glucose (Hames and Higgins, 1995) with 0 or 6.5% (w/v) NaCl.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

The primers SH3a (5′-GGAATTCCATATGCAGGAAGAGATCAA-3′) and SH3b (5′-CGCCCGGGAAGGGCATCACTGTTGCTTGG-3′) were used to amplify the coding region for the predicted SH3 domain of AtSH3P1. The fragment was cloned into pAS1-CYH2 in frame with the GAL4 DNA binding domain. The pAS1-CYH2-SH3 construct was cotransformed with an Arabidopsis seedling pACT cDNA library (from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center) into yeast strain Y190. Cotransformants were screened for the activation of the HIS and β-galactosidase reporters (Breeden and Nasmyth, 1985). To verify an SH3-dependent interaction between AtSH3P1 and auxilin-like protein, the following constructs were made. The full-length cDNA for AtSH3P1 was amplified by FLa (5′-GGAATTCCATATGGAAGCTATAAGAA-3′) and SH3b. The cDNA coding for AtSH3P1 with the SH3 domain deleted was amplified by FLa and NT (5′-CTCGAT-GGACTAGACTTAATTTC-3′). The DNA fragments were cloned into pAS1-CYH2 to give pAS1-CYH2-AtSH3P1 or pAS1-CYH2-NT. The pACT-auxilin rescued from the screen described above was cotransformed into Y190 with pAS1-CYH2-AtSH3P1 or pAS1-CYH2-NT. The interactions were quantified as described (Ausubel et al., 1994).

GST Pulldown Assay

Soluble lysate, in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF) supplemented with 1% Triton X-100, from Escherichia coli strain BL21 (pLys) expressing GST, GST-AtSH3P1, or GST-auxilin–like protein was allowed to bind to glutathione–agarose resin (Sigma). After thorough washing in binding buffer, the GST-glutathione complexes were incubated with ∼0.5 mg of Arabidopsis cytosol, obtained as described above, in a total volume of 200 μL. The complex then was washed three times with binding buffer supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) Triton X-100. The GST or GST fusion proteins and their binding partner(s) were eluted by incubating the resin with 10 mM reduced glutathione in binding buffer for 20 min at room temperature.

Uncoating of Clathrin from Microsomal Membranes

Uncoating of clathrin from Arabidopsis microsomal membranes was performed according to Ungewickell et al. (1995) with slight modifications. Microsomal membrane was obtained as described above. The membrane then was centrifuged at 100,000g for 45 min in a Beckman TLA100 rotor to remove any free clathrin not associated with the membrane. The pellet was resuspended in the reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 μM creatine phosphate, and 5 units/mL creatine phosphokinase [Calbiochem]) to give a final protein concentration of ∼2 mg/mL. Two micrograms of AtSH3P1, GST-auxilin–like protein, bovine Hsc70 (Calbiochem), or combinations of these proteins were added to 30 μg of the resuspended microsomal membrane. Two millimolar ATP then was added to start the reactions for 45 min at room temperature. The reactions were centrifuged at 100,000g for 20 min. The resulting supernatant and pellets were collected and subjected to protein gel blotting.

Accession Numbers

The GenBank accession numbers for AtSH3P1, AtSH3P2, and AtSH3P3 are AF367773, AF367774, and AF367775, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Brenda Andrews for the yeast strains, Dr. Anthony Jackson for the anti-plant clathrin antibodies, and Dr. Ramon Serrano for the anti-AHA3 antibodies. This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to T.L.S. and E.B. and the Will W. Lester Endowment from the University of California to E.B. B.C.-H.L. was a recipient of an Ontario Graduate Scholarship.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.aspb.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.010279.

References

- Aharon, G.S., Gelli, A., Snedden, W.A., and Blumwald, E. (1998). Activation of a plant plasma membrane Ca2+ channel by TGα1, a heterotrimeric G protein α-subunit homologue. FEBS Lett. 424 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahle, S., and Ungewickell, E. (1990). Auxilin, a newly identified clathrin-associated protein in coated vesicles from bovine brain. J. Cell Biol. 111 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, F.M., Brent, R., Kingston, R.E., Moore, D.D., Seidman, J.G., Smith, J.A., and Struhl, K. (1994). Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. (New York: Wiley).

- Battey, N.H., James, N.C., Greenland, A.J., and Brownlee, C. (1999). Exocytosis and endocytosis. Plant Cell 11 643–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, B., Wilson, D.B., Wolf, E., Tonchev, T., Milla, M., and Kim, P.S. (1995). Predicting coiled coils by use of pairwise residue correlations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 8259–8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackbourn, H.D., and Jackson, A.P. (1996). Plant clathrin heavy chain: Sequence analysis and restricted localisation in growing pollen tubes. J. Cell Sci. 109 777–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeden, L., and Nasmyth, K. (1985). Regulation of the yeast HO gene. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 50 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodin, L., Löw, P., and Shupliakov, O. (2000). Sequential steps in clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cestra, G., Castagnoli, L., Dente, L., Minenkova, O., Petrelli, A., Migone, N., Hoffmüller, U., Schneider-Mergener, J., and Cesareni, G. (1999). The SH3 domains of endophilin and amphiphysin bind to the proline-rich region of synaptojanin 1 at distinct sites that display an unconventional binding specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 274 32001–32007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwill, K., Field, D., Moore, L., Friesen, J., and Andrews, B. (1999). In vivo analysis of the domains of yeast Rvs167p suggests Rvs167p function is mediated through multiple protein interactions. Genetics 152 881–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David, C., McPherson, P.S., Mundigl, O., and De Camilli, P. (1996). A role of amphiphysin in synaptic vesicle endocytosis suggested by its binding to dynamin in nerve terminals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 331–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drubin, D.G., Mulholland, J., Zhu, Z.M., and Botstein, D. (1990). Homology of a yeast actin-binding protein to signal transduction proteins and myosin-I. Nature 343 288–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S., Chen, J.K., Yu, H., Simon, J.A., and Schreiber, S.A. (1994). Two binding orientation for peptides to the Src SH3 domain: Development of a general model for SH3-ligand interactions. Science 266 1241–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gad, H., Ringstad, N., Löw, P., Kjaerulff, O., Gustafsson, J., Wenk, M., Di Paolo, G., Nemoto, Y., Crum, J., Ellisman, M.H., De Camilli, P., Shupliakov, O., and Brodin, L. (2000). Fission and uncoating of synaptic clathrin-coated vesicles are perturbed by disruption of interactions with the SH3 domain of endophilin. Neuron 27 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall, W.E., Higginbotham, M.A., Chen, C., Ingram, M.F., Cyr, D.M., and Graham, T.R. (2000). The auxilin-like phosphoprotein Swa2p is required for clathrin function in yeast. Curr. Biol. 10 1349–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X., and Verma, D.P. (1996). Phragmoplastin, a dynamin-like protein associated with cell plate formation in plants. EMBO J. 15 695–704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hames, B.D., and Higgins, S.J. (1995). Gene Probe: A Practical Approach. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press).

- Harlow, E., and Lane, D. (1988). Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Hawes, C. (1994). Electron microscopy. In Plant Cell Biology: A Practical Approach, N. Harris and K.J. Oparka, eds (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press). pp. 83–85.

- Holstein, S.E., Drucker, M., and Robinson, D.G. (1994). Identification of a β-type adaptin in plant clathrin-coated vesicles. J. Cell Sci. 107 945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner, W.B., and Schmidt, A. (2000). Lipids, lipid modification and lipid-protein interaction in membrane budding and fission: Insights from the roles of endophilin A1 and synaptophysin in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10 543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.F., Greener, T., Barouch, W., Greene, L., and Eisenberg, E. (1997). Interaction of auxilin with the molecular chaperone, Hsc70. J. Biol. Chem. 272 6141–6145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leto, T.L., Lomax, K.J., Volpp, B.D., Nunoi, H., Sechler, J.M., Nauseef, W.M., Clark, R.A., Gallin, J.I., and Malech, H.L. (1990). Cloning of a 67kD neutrophil oxidase factor with similarity to a noncatalytic region of p60c-src. Science 248 727–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lila, T., and Drubin, D. (1997). Evidence for physical and functional interactions among two Saccharomyces cerevisiae SH3 domain proteins, an adenylyl cyclase-associated protein and the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 8 367–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein, E.J., Daly, R.J., Batzer, A.G., Li, W., Margolis, B., Lammers, R., Ullrich, A., and Schlessinger, J. (1992). The SH2 and SH3 domain-containing protein GRB2 links receptor tyrosine kinases to ras signaling. Cell 70 431–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas, A. (1996). Coiled coils: New structures and new functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21 375–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, M., and McMahon, H.T. (1999). The structural era of endocytosis. Science 285 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, T.F.J. (1998). Phosphoinositide lipids as signaling molecules: Common themes for signal transduction, cytoskeletal regulation, and membrane trafficking. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14 231–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, B.J., and Eck, M.J. (1995). Minding your p's and q's. Curr. Biol. 5 364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, P., Bessoule, J.J., Mongrand, S., Testet, E., Vincent, P., and Cassagne, C. (1998). Lipid trafficking in plant cells. Prog. Lipid Res. 37 371–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musaccho, A., Wilmanns, M., and Saraste, M. (1994). Structure and function of the SH3 domain. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 61 283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, S., and Miki-Hirosige, H. (1982). Coated vesicles and cell plate formation in the microspore mother cell. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 80 302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.M., Cho, J.H., Kang, S.G., Jang, H.J., Pih, K.T., Piao, H.L., Cho, M.J., and Hwang, I. (1998). A dynamin-like protein in Arabidopsis thaliana is involved in biogenesis of thylakoid membranes. EMBO J. 17 859–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, T. (1995). Protein modules and signalling networks. Nature 373 573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann, B., and Kelly, R.B. (2000). Syndapin isoforms participate in receptor-mediated endocytosis and actin organization. J. Cell Biol. 148 1047–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringstad, N., Nemoto, Y., and De Camilli, P. (1997). The SH3p4/SH3p8/SH3p13 protein family: Binding partners for synaptojanin and dynamin via a Grb2-like Src homology 3 domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94 8569–8574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronicke, V., Graulich, W., Mumberg, D., Muller, R., and Funk, M. (1997). Use of conditional promoters for expression of heterologous proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 283 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos, J., and Kelly, R.B. (1998). Dap160, a neural-specific Eps15 homology and multiple SH3 domain-containing protein that interacts with Drosophila dynamin. J. Biol. Chem. 273 19108–19119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderfoot, A.A., Ahmed, S.U., Marty-Mazars, D., Rapoport, I., Kirchhausen, T., Marty, F., and Raikhel, N.V. (1998). A putative vacuolar cargo receptor partially colocalizes with AtPEP12p on a prevacuolar compartment in Arabidopsis roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 9920–9925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A., Wolde, M., Thiele, C., Fest, W., Kratzin, H., Podtelejnikov, A.V., Witke, W., Huttner, W.B., and Söling, H.-D. (1999). Endophilin I mediates synaptic vesicle formation by transfer of arachidonate to lysophosphatidic acid. Nature 401 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, J., Milpetz, F., Bork, P., and Ponting, C.P. (1998). SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: Identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 5857–5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg, P.L. (1998). The many faces of Src: Multiple functions of a prototypical tyrosine kinase. Oncogene 17 1463–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger, A.S., Wang, W., Bishay, J., Cohen, S., and Egan, S.E. (1999). The EH and SH3 domain Ese proteins regulate endocytosis by linking dynamin and Eps15. EMBO J. 18 1159–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shupliakov, O., Löw, P., Grabs, D., Gad, H., Chen, H., David, C., Takei, K., De Camilli, P., and Brodin, L. (1997). Synaptic vesicle endocytosis impaired by disruption of dynamin-SH3 domain interactions. Science 276 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurr, A.R. (1969). A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 26 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, J.M., Imara, Y.P., and Boss, W.F. (1998). A phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase pleckstrin homology domain that binds phosphatidylinositol 4-monophosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 273 22761–22767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J., and Douglas, M.G. (1996). A conserved HPD sequence of the J-domain is necessary for YDJ1 stimulation of Hsp70 ATPase activity at a site distinct from substrate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 271 9347–9354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungewickell, E., Ungewickell, H., Holstein, S.E., Lindner, R., Prasad, K., Barouch, W., Martin, B., Greene, L.E., and Eisenberg, E. (1995). Role of auxilin in uncoating clathrin-coated vesicles. Nature 378 632–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland, B., and Emr, S.D. (1998). Pan1p, yeast eps15, functions as a multivalent adaptor that coordinates protein-protein interactions essential for endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 141 71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge, P., and McMahon, H.T. (1998). The amphiphysin family of proteins and their role in endocytosis at the synapse. Trends Neurosci. 21 339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamabhai, M., Hoffman, N.G., Hardison, N.L., McPherson, P.S., Castagnoli, L., Cesareni, G., and Kay, B.K. (1998). Intersectin, a novel adaptor protein with two Eps15 homology and five Src homology 3 domains. J. Biol. Chem. 273 31401–31407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota, E., Takahar, K., and Shimmen, T. (1998). Actin-bundling protein isolated from pollen tubes of lily. Plant Physiol. 116 1421–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]