Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether breast feeding is effective for pain relief during venepuncture in term neonates and compare any effect with that of oral glucose combined with a pacifier.

Design

Randomised controlled trial.

Participants

180 term newborn infants undergoing venepuncture; 45 in each group.

Interventions

During venepuncture infants were either breast fed (group 1), held in their mother's arms without breast feeding (group 2), given 1 ml of sterile water as placebo (group 3), or given 1 ml of 30% glucose followed by pacifier (group 4). Video recordings of the procedure were assessed by two observers blinded to the purpose of the study.

Main outcome measures

Pain related behaviours evaluated with two acute pain rating scales: the Douleur Aiguë Nouveau-né scale (range 0 to 10) and the premature infant pain profile scale (range 0 to 18).

Results

Median pain scores (interquartile range) for breast feeding, held in mother's arms, placebo, and 30% glucose plus pacifier groups were 1 (0-3), 10 (8.5-10), 10 (7.5-10), and 3 (0-5) with the Douleur Aiguë Nouveau-né scale and 4.5 (2.25-8), 13 (10.5-15), 12 (9-13), and 4 (1-6) with the premature infant pain profile scale. Analysis of variance showed significantly different median pain scores (P<0.0001) among the groups. There were significant reductions in both scores for the breast feeding and glucose plus pacifier groups compared with the other two groups (P<0.0001, two tailed Mann-Whitney U tests between groups). The difference in Douleur Aiguë Nouveau-né scores between breast feeding and glucose plus pacifier groups was not significant (P=0.16).

Conclusions

Breast feeding effectively reduces response to pain during minor invasive procedure in term neonates.

What is already known on this topic

Current pharmacological treatments are not appropriate for pain relief during minor procedures like venepuncture or heel prick in newborn infants

Oral sweet solutions, non-nutritive sucking, and skin to skin contact reduce procedural pain in newborn infants

What this study adds

Breast feeding during a painful procedure effectively reduces the response to pain in newborn infants

The analgesic properties of breast feeding are at least as potent as the combination of sweet solutions and a pacifier

Introduction

Newborn infants routinely undergo painful invasive procedures, even after uncomplicated birth. Evidence shows that neonates do feel pain1 and may even have increased sensitivity to pain and to its long term effects compared with older infants.2 Treating procedural pain has become a crucial part of neonatal care. In healthy infants, the most common painful procedures are heel lance and venepuncture. Pharmacological treatments are rarely used during these procedures because of concerns about their effectiveness (topical local anaesthetic3 or paracetamol for heel pricks4) and potential adverse effects (central analgesics). Therefore, non-pharmacological interventions are valuable alternatives.

Recent studies have reported that pain can be reduced with simple and benign interventions such as sweet oral solutions (sucrose or glucose) and non-nutritive sucking5–8 or multisensory stimulation.9 More recently, Gray et al reported that 10 to 15 minutes of skin to skin contact between mothers and infants reduced crying, grimacing, and heart rate during heel lance procedures.10 Environmental and behavioural strategies have been considered essential to the prevention and management of neonatal pain.11 As breast feeding probably constitutes the most potent pleasant stimulation a newborn infant can experience we hypothesised that breast feeding could have analgesic properties in neonates.

We investigated the efficacy of breast feeding for pain relief during venepuncture in term neonates and compared any effect with that of oral glucose combined with a pacifier.

Methods

Protocol

The study took place in the maternity ward of one hospital. We obtained written informed consent from both parents of each newborn infant included. Included infants were all born at ⩾37 weeks' gestation; had APGAR scores ⩾7 at 5 minutes; were aged ⩾24 hours; were undergoing venepuncture as part of routine medical care; were breast fed; and had not been fed for the previous 30 minutes. In all cases the investigator (SV) prepared all inclusions and videotaped procedures. He was present eight hours every day from Monday to Friday, at the time when most non-urgent blood samples were drawn. We excluded infants with medical instability, those who had received naloxone during the previous 24 hours, and those who had received a sedative or a major analgesic during the previous 48 hours.

The study protocol and the letter of permission addressed to parents were approved by the local ethics committee.

Procedures and masking

Participating infants and their mothers were taken to a quiet nursery room for venepuncture. SV opened a consecutively numbered envelope, which contained the treatment assigned to each infant. Infants were allocated to one of four groups: in group 1 they were breast fed, starting two minutes before the procedure and continuing throughout; in group 2 they were held in their mother's arms without breast feeding, starting two minutes before the procedure; in group 3 two minutes before the procedure infants were laid on a table and given 1 ml of placebo (sterile water) without a pacifier; and in group 4 two minutes before the procedure infants were laid on a table and given 1 ml of 30% glucose followed by sucking a pacifier. The infant's legs and feet were uncovered to allow observation of movements. Infants in groups 3 and 4 lay supine on an examination table during procedures.

The water or 30% glucose was administered for about 15 seconds by a sterile syringe into the infant's mouth. In group 4 the pacifier (standard nipple stuffed with a gauze square for resistance) was held gently in the infant's mouth by an assistant throughout the procedure. Infants' heart rate and oxygen saturation were monitored with a Nellcor monitor (model N-395). The infants and the monitor screen were video recorded during the procedure. Venepuncture was performed on the dorsal aspect of the infant's hand by one of three experienced nurses.

When all inclusions were completed two specially trained observers independently assessed the recordings using the Douleur Aiguë Nouveau-né (DAN) scale (primary outcome measure) and the premature infant pain profile (PIPP) scale (secondary outcome measure). They assessed arousal state using Prechtl's observational rating system12: (1) eyes closed, regular respiration, no movements; (2) eyes closed, irregular respiration, gross movements; (3) eyes open, no gross movements; (4) eyes open, continual gross movements, no crying; (5) eyes open or closed, fussing, or crying. Assessement of pain started when the needle was inserted and ended when it was removed. Observers could stop and restart the videotape as many times as they needed to establish a score. These observers were blinded to the purpose and hypothesis of the study. They had been told that we were assessing agreement of their scores in four different situations. For the DAN scale there was good agreement between both observers on initial evaluation (Krippendorf's r=92.7). The two observers subsequently re-evaluated all the procedures for which scores had not been identical during their first assessment (92 for DAN and 138 for the PIPP scores). This yielded final sets of pain scores that reflected perfect agreement between two observers.

We interviewed mothers 48 to 72 hours after venepuncture using a standardised questionnaire to determine if they had noticed any changes in the way their infants sucked their breast after the procedure to determine whether venepuncture during feeding made sucking less effective.

Sample calculation

We calculated that we would need 40 infants in each group to detect a 2 point difference in DAN scale with 80% power and at 1% significance. We decided to include 45 neonates in each group to cover potential problems with video recordings.

Pain scales

The DAN scale is a behavioural scale developed to rate acute pain in term and preterm neonates.13 Scores range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum pain). It evaluates three items: facial expressions, limb movements, and vocal expression (table 1). The scale is sensitive if all scores are obtained and is specific if it differentiates painful from non-painful procedures (⩾3 in 95% of painful procedures and ⩽2 in 88% of dummy procedures). There was good internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0.88) and good agreement between raters (Krippendorf's r=91.2).

Table 1.

Douleur Aiguë Nouveau-né behavioural scale for rating acute pain in neonates

| Score

|

|

|---|---|

| Facial expressions | |

| Calm | 0 |

| Snivels and alternates gentle eye opening and closing | 1 |

| Intensity of eye squeeze, brow bulge, nasolabial furrow: | |

| Mild, intermittent with return to calm* | 2 |

| Moderate† | 3 |

| Very pronounced, continuous‡ | 4 |

| Limb movements | |

| Calm or gentle movements | 0 |

| Intensity of pedalling, toes spread, legs tensed and pulled up, agitation of arms, withdrawal reaction: | |

| Mild, intermittent with return to calm* | 1 |

| Moderate† | 2 |

| Very pronounced, continuous‡ | 3 |

| Vocal expression | |

| No complaints | 0 |

| Moans briefly (for intubated child, looks anxious or uneasy) | 1 |

| Intermittent crying (for intubated child, expression of intermittent crying) | 2 |

| Longlasting crying, continuous howl (for intubated child, expression of continuous crying) | 3 |

Present during <1/3 of observation periods.

Present during 1/3 to 2/3 of observation periods.

Present during >2/3 of observation periods.

The PIPP scale is a multidimensional measure developed to assess acute pain in preterm and term infants.14 It measures gestational age, behavioural state, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and three facial reactions (brow bulge, eye squeeze, nasolabial furrow). In term infants, scores range from 0 (no pain) to 18 (maximum pain).

Assignment

We randomly assigned infants to four groups. An assistant not involved in the study performed the randomisation in advance in blocks of 20 using a random number table. Treatment allocations were placed in opaque sealed envelopes numbered 1-180; investigators were blind to these allocations. Codes of allocation were kept secret by the assistant who performed randomisation, and they were broken only after all videotape assessments were accomplished.

Statistical analysis

Most of the statistical analysis was performed with NCSS 2001 software. We used Kruskal-Wallis one way analysis of variance on ranks to compare overall differences among four groups. We compared median pain scores of all groups using two tailed Mann-Whitney U tests. Because five pairwise planned comparisons were made we considered P<0.01 as significant. We used χ2 tests to compare categorical variables. Confidence intervals of median difference among groups were determined with Minitab 13 software. Krippendorf's r was obtained with SIMSTAT 3.5.

Results

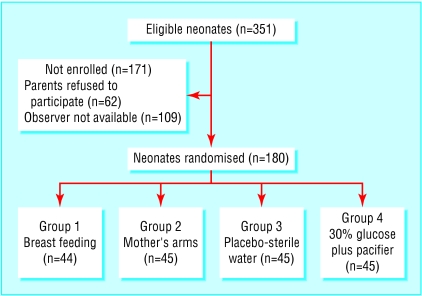

During the study period (February to June 2001) 351 infants met the inclusion criteria. Of these 180 were allocated to one of four equal sized groups. Figure 1 shows a trial profile with participant flow. The perinatal characteristics of neonates not included in the study were similar to those included. Table 2 shows perintal characteristics for each group. There were no substantial differences among the groups except for arousal state. Table 3 shows the reasons for venepuncture. All procedures were carried out between 9 am and 3 pm.

Figure 1.

Trial profile and participant flow. All but one randomised infant completed trial. In group 1 one infant was excluded from analysis because her face was covered by her mother's head during half the procedure

Table 2.

Perinatal characteristics of 179 newborn infants included in study of analgesic effects of breast feeding

| Breast feeding (n=44)

|

Mother's arms (n=45)

|

Placebo-sterile water (n=45)

|

30% sucrose plus pacifier (n=45)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) gestational age (weeks) | 39.7 (1.15) | 39.8 (1.23) | 40.0 (1.14) | 39.6 (1.20) |

| Mean (SD) birth weight (g) | 3306 (382.8) | 3304 (483.0) | 3420 (418.8) | 3313 (401.2) |

| Boys/girls | 23/21 | 24/21 | 22/23 | 24/21 |

| Vaginal/caesarean delivery | 38/6 | 38/7 | 40/5 | 40/5 |

| Median (range) Apgar score at 5 min | 10 (9-10) | 10 (8-10) | 10 (8-10) | 10 (9-10) |

| Median (range) postnatal age (days) | 3 (2-5) | 3 (1-6) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (1-5) |

| Median (range) state of arousal | 2 (1-5) | 3 (1-5) | 3 (1-5) | 3 (1-5) |

| Mean (SD) time between last feed and procedure (min) | 130.1 (71.5) | 106.7 (62.7) | 130.2 (80.4) | 125.2 (74.5) |

Table 3.

Reasons for venepuncture

| No of neonates*

|

|

|---|---|

| Hypothyroidism and phenylketonuria screening | 162 |

| Bilirubin | 53 |

| C reactive protein | 74 |

| Sickle cell disease screening | 17 |

| Calcium | 13 |

| Blood typing | 6 |

Some had more than one reason to undergo venepuncture.

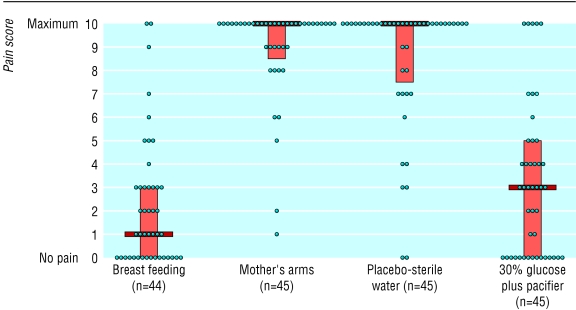

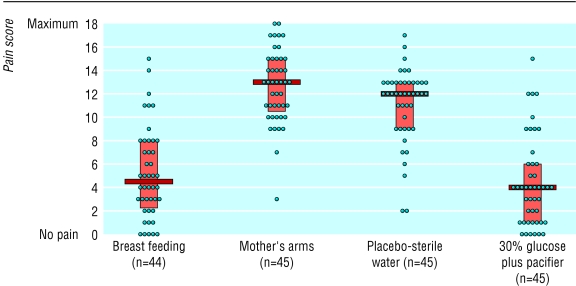

Figures 2 and 3 show individual pain scores, median values, and interquartile ranges for each group during venepuncture. The median pain scores (interquartile range) during venepuncture for group 1 (breast feeding), group 2 (held in mother's arms), group 3 (placebo), and group 4 (30% glucose plus pacifier) were 1 (0-3), 10 (8.5-10), 10 (7.5-10), and 3 (0-5) with the DAN scale and 4.5 (2.25-8), 13 (10.5-15), 12 (9-13), and 4 (1-6) with PIPP scale. Analysis of variance showed that median pain scores were significantly different (P<0.0001). Tables 4 and 5 show pairwise comparisons of median pain scores.

Figure 2.

Pain during venepuncture in 179 infants according to Douleur Aiguë Nouveau-né (DAN) scale (0 to 10). Median values, interquartile ranges, and individual values

Figure 3.

Pain during venepuncture in 179 infants according to premature infant pain profile (PIPP) scale (0 to 18). Median values, interquartile ranges, and individual values

Table 4.

Median pain scores (MPS) among four groups of neonates with Douleur Aiguë Nouveau-né scale* during venepuncture. Figures are estimated median difference (95% confidence interval)

| Breast feeding (MPS=1)

|

Placebo (MPS=10)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Mother's arms (MPS=10) | 7 (7 to 8), P<0.0001† | 0 (0 to 0), P=1† |

| Placebo-sterile water (MPS=10) | 7 (6 to 8), P<0.0001† | NA |

| 30% glucose plus pacifier (MPS=3) | 0 (0 to 2), P=0.16† | 6 (5 to 7), P<0.0001† |

NA=not applicable.

0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum pain).

For two sided Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 5.

Comparisons of median pain scores (MPS) among four groups of neonates with premature infant pain profile scale* during venepuncture. Figures are estimated median difference (95% confidence interval)

| Breast feeding (MPS=4.5)

|

Placebo (MPS=12)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Mother's arms (MPS=13) | 8 (6 to 9), P<0.0001† | 1 (0 to 3), P=0.38† |

| Placebo-sterile water (MPS=12) | 7 (5 to 8), P<0.0001† | NA |

| 30% glucose plus pacifier (MPS=4) | 1 (−1 to 2), P=0.28† | 8 (6 to 9), P<0.0001† |

NA=not applicable.

0 (no pain) to 18 (maximum pain).

For two sided Mann-Whitney U test.

We obtained information on sucking after the procedure in 156 neonates. Mothers subjectively compared their infant's sucking before and during the 48 to 72 hours after the procedure; sucking was the same in 32/37, 38/40, 34/40, and 38/39 neonates in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Sucking was more effective in 5/37, 2/40, 6/40, 1/39 neonates, respectively (P=0.14 for χ2 with 3 df). Infants who undergo venepuncture while they are being breast fed do not subsequently suck less effectively.

Discussion

Our study has shown that breast feeding throughout a painful procedure is analgesic in term neonates. Of 44 infants in the breastfeeding group, 16 showed no indication at all that the venepuncture and blood sampling had even occurred; 35 had a DAN pain score ⩽3, which can be considered as reflecting minimal or no pain. Our findings are clinically important as they show that natural protective mechanisms may safely and non-invasively be activated by breast feeding during medical procedures.

We detected no reduction in response to pain in infants who were simply held in their mother's arms. These infants were dressed and did not have a skin to skin contact with their mothers. Gray et al found that 10 to 15 minutes' skin to skin contact between a mother and baby reduces the infant's response to pain during heel stick.10 To our knowledge, there have been only two previous reports on the analgesic effect of breast feeding. Bilgen et al compared the analgesic effects of sucrose, expressed breast milk, and breast feeding during heel pricks. Breast feeding was allowed for two minutes and stopped before a heel prick.15 There was no analgesic effect of this type of intervention, possible because breast feeding was not continued during the procedure. Recently Gray et al reported that breast feeding before, during, and after heel prick markedly reduced crying and grimacing and prevented the increase in heart rate in term neonates compared with swaddled infants in their cots.16 No other groups were included in their study design. In Gray's study infants in the breastfeeding group were held in full body skin to skin contact during the entire procedure.

Study limitations

We acknowledge three potential limitations in our study. Firstly, observers obviously recognised the four groups when they were evaluating the recordings. However, they did not know the purpose of the study. Moreover, high agreement among observers during initial evaluations indicates objectivity. Secondly, although the DAN scale has been shown to discriminate pain in term newborn infants, no study has yet proved that it can grade the degree of perception of pain. We assumed that the more pronounced the facial expressions, limb movements, and vocal expressions, the higher the pain in the infant. Nevertheless, the robustness of pain evaluation was supported by the fact that the simultaneous use of the PIPP scale yielded similar results. Finally, median score for state of arousal was lower in the breastfeeding group than in the other groups. This difference was slight and in our opinion was insufficient to explain all differences observed in pain scores among groups.

Minor procedures are common in term newborn infants, even when they are doing well. There is no valid reason to withhold effective analgesia. Current pharmacological treatments are not appropriate for acute, repetitive, and shortlasting procedures, and non-pharmacological approaches therefore constitute important treatment options. To date the most potent non-pharmacological analgesia reported has been the use of a pacifier combined with a sweet solution. We have shown that breast feeding is at least as effective as that observed with 30% glucose plus sucking a pacifier. We believe that breast feeding is an excellent natural alternative to prevent or reduce pain during minor daily procedures undergone by neonates.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nursing staff of the maternity ward of the Poissy Hospital for their help during the study. We also thank Nicolas Simon, chief of the emergency department of the Poissy Hospital, for reading the manuscript. We are indebted to the parents for allowing their infants to participate in the study.

Footnotes

Funding: Fondation pour la Santé CNP, France.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Anand KJS the International Evidence-Based Group for Neonatal Pain. Consensus statement for the prevention and management of pain in the newborn. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:173–180. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand KJS. Clinical importance of pain and stress in preterm newborn infants. Biol Neonate. 1998;73:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000013953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taddio A, Ohlsson A, Einarson TR, Stevens B, Koren G. A systematic review of lidocaine-prilocaine cream (EMLA) in the treatment of acute pain in neonates. Pediatrics. 1998;101(2):E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.2.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah A, Taddio A, Ohlsson A. Randomised controlled trial of paracetamol of heel prick pain in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;79:F209–F211. doi: 10.1136/fn.79.3.f209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stevens B, Taddio A, Ohlsson A, Einarson T. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(4):CD001069. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Skogsdal Y, Eriksson M, Schollin J. Analgesia in newborns given oral glucose. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:217–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carbajal R, Chauvet X, Couderc S, Olivier-Martin M. Randomised trial of analgesic effects of sucrose, glucose, and pacifiers in term neonates. BMJ. 1999;319:1393–1397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7222.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blass EM, Watt LB. Suckling- and sucrose-induced analgesia in human newborns. Pain. 1999;83:611–623. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellieni CV, Bagnoli F, Perrone S, Nenci A, Cordelli DM, Fusi M, et al. Effect of multisensory stimulation on analgesia in term neonates: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Res. 2002;51:460–463. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray L, Watt L, Blass EM. Skin-to-skin contact is analgesic in healthy newborns. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1):E14. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franck L, Lawhon G. Environmental and behavioral strategies to prevent and manage neonatal pain. In: Anand KJS, Stevens BJ, McGrath PJ, editors. Pain in neonates. 2nd rev ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prechtl HFR. The neurological examination of the full term newborn infant. In: Prechtl HFR, editor. Clinics in developmental medicine. 2nd rev ed. London: Heinemann; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carbajal R, Paupe A, Hoenn E, Lenclen R, Olivier-Martin M. Douleur Aiguë Nouveau-né: une échelle comportementale d'évaluation de la douleur aiguë du nouveau-né. [APH: evaluation of behavioural scale of acute pain in newborn infants.] Arch Pediatr. 1997;4:623–628. doi: 10.1016/s0929-693x(97)83360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens B, Johnston C, Petryshen P, Taddio A. Premature infant pain profile: development and initial validation. Clin J Pain. 1996;12:13–22. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilgen H, Ozek E, Cebeci D, Ors R. Comparison of sucrose, expressed breast milk, and breast-feeding on the neonatal responses to heel prick. J Pain. 2001;2:301–305. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2001.23140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray L, Miller LW, Philipp BL, Blass EM. Breastfeeding is analgesic in healthy newborns. Pediatrics. 2002;109:590–593. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]