Abstract

We report the isolation and preliminary characterization of BTF-37, a new 52-kb transfer factor isolated from Bacteroides fragilis clinical isolate LV23. BTF-37 was obtained by the capture of new DNA in the nonmobilizable Bacteroides-Escherichia coli shuttle vector pGAT400ΔBglII using a functional assay. BTF-37 is self-transferable within and from Bacteroides and also self-transfers in E. coli. Partial DNA sequencing, colony hybridization, and PCR revealed the presence of Tet element-specific sequences in BTF-37. In addition, Tn5520, a small mobilizable transposon that we described previously (G. Vedantam, T. J. Novicki, and D. W. Hecht, J. Bacteriol. 181:2564–2571, 1999), was also coisolated within BTF-37. Scanning and transmission electron microscopy of Tet element-containing Bacteroides spp. and BTF-37-harboring Bacteroides and E. coli strains revealed the presence of pilus-like cell surface structures. These structures were visualized in Bacteroides spp. only when BTF-37 and Tet element strains were induced with subinhibitory concentrations of tetracycline and resembled those encoded by E. coli broad-host-range plasmids. We conclude that we have captured a new, self-transferable transfer factor from B. fragilis LV23 and that this new factor encodes a tetracycline-inducible Bacteroides sp. conjugation apparatus.

Horizontal DNA transfer by conjugation is widespread in the bacterial world and has been responsible in part for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (22, 59). Conjugation between bacterial genera and species and also interkingdom conjugation (bacteria to yeast and bacteria to plants [6)]) have been shown to occur. While mobile genetic elements such as plasmids and transposons are most frequently transferred by conjugation, segments of chromosomal DNA can also be transferred by this process (17, 31).

Members of the genus Bacteroides are obligate, gram-negative, colonic anaerobes. Bacteroides spp. possess a plethora of mobile transfer factors, many of which harbor antibiotic resistance genes. These factors have been shown to transfer within and from Bacteroides, thus implicating these organisms as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance (A. A. Salyers, Letter, ASM News 65:459–460, 1999).

DNA transfer by conjugation involves two major sets of processes: initiation and mating apparatus formation. Initiation results in the formation of a relaxosome, an ordered assembly of proteins that nick the DNA to be transferred in a site- and strand-specific manner (32, 44, 45, 65). This nicked DNA is unwound and transmitted with 5′-3′ polarity from the donor to the recipient. In Escherichia coli, the passage from donor to recipient is thought to occur through a specialized membrane-traversing channel. The channel and all accessory proteins required for mating pair stabilization, cell-cell contact, surface and entry exclusion, and DNA transfer are collectively referred to as the mating apparatus. For the E. coli F and RP4 plasmids and the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid, it is thought that at least 21, 12, and 12 gene products, respectively, are involved in mating apparatus formation (2, 20, 34, 35). For Bacteroides, although preliminary information on initiation processes is available (one to three gene products are involved depending on the transfer factor) (40, 41, 43, 47, 54, 55, 61), there are no reports on the existence or nature of a mating apparatus.

Bacteroides sp. organisms harbor both conjugative and mobilizable elements (49, 50, 56). Conjugative elements may be plasmids or transposons that are self-transferable, i.e., they encode functions for both DNA initiation and mating apparatus formation. Mobilizable elements may also be plasmids or transposons and appear to encode only DNA initiation functions. These factors presumably use the mating apparatus of a coresident conjugative element for transfer to a recipient cell. Conjugative transposons (cTns) in Bacteroides are chromosomally located and are referred to as Tet elements since they carry the tetracycline resistance gene tetQ (and may also harbor other resistance-encoding genes). These elements are widespread in Bacteroides (50, 51). In addition to tetQ, Tet elements also harbor the rteABC gene cluster, which is involved in the regulation of Tet element transfer (50, 57).

Bacteroides sp. strains harboring Tet elements are responsive to very low (subinhibitory) levels of tetracycline or its analogs, and a brief exposure results in a markedly elevated (1,000- to 10,000-fold) frequency of transfer of the Tet element and other coresident factors. The complete mechanism of this “Tet induction” and induction-enhanced conjugation frequency is unknown but appears to involve the rte gene cluster (57). It has also been consistently observed that transfer of mobilizable elements within and from Bacteroides occurs only when Tet elements are coresident (62), leading to the speculation that the Bacteroides mating apparatus may be carried on Tet elements. The sequence of the transfer region for Tet element cTnDOT has become available recently (7), but the predicted products of the newly identified open reading frames (ORFs) do not show homology to known mating apparatus proteins from other organisms. No complete sequence or other analysis is available for any other Tet elements to date.

We report here the capture of a new Tet element-related transfer factor from Bacteroides fragilis clinical isolate LV23. This new factor was isolated by its capture in a shuttle vector using a functional assay and was designated BTF-37. We have completed the initial characterization of BTF-37 with respect to its transfer properties in Bacteroides spp. and E. coli and have studied the external morphology of BTF-37 and other Tet element-harboring bacteria. Partial DNA sequencing of BTF-37 revealed the presence of various ORFs including those which appear to be homologs of Tet element-specific genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Media, antibiotics, and growth conditions for Bacteroides spp. and E. coli have been previously described (43). Antibiotic concentrations used for the selection of strains and plasmids included the following: ampicillin, 200 μg/ml; clindamycin, 12 μg/ml; streptomycin, 50 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 50 μg/ml; rifampin, 25 μg/ml; trospectomycin, 25 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; trimethoprim, 100 μg/ml; tetracycline, 10 (for E. coli) or 5 μg/ml (for Bacteroides spp.). E. coli strains containing R751 were grown in Mueller-Hinton medium (Difco); other E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic when required. Bacteroides spp. were grown in BHIS medium (3.7% brain heart infusion medium supplemented with 0.0005% hemin and 5 g of yeast extract/liter) in a Coy anaerobic chamber (5% CO2, 10% H2, and 85% N2).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Marker and transfer potentiala | Source or description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| B. fragilis | |||

| LV23 | Tetr Tra+ | Clinical isolate | |

| TM4000 | Rifr Tra− | 54 | |

| TM429 | Rifr Trsr Tra− | 26 | |

| TM4.23 | Tetr Rifr Tra+ | 54 | |

| LV22 | Tetr Tra+ | Clinical isolate | |

| LV25 | Tetr Tra+ | Clinical isolate | |

| LV43 | Tetr Tra+ | Clinical isolate | |

| B. thetaiotaomicron | |||

| OBT4001 | Rifr Tra− | 53 | |

| E. coli | |||

| HB101 | Smr | 54 | |

| DW1030 | Spr | 54 | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pGAT400ΔBglII | Apr Clnr TetX*r | Shuttle vector | 25 |

| pHB23Δ5 | Apr Clnr TetX*r | Tn5520 insertion in pGAT400ΔBglII | 54 |

| BTF-37 | Apr Clnr TetX*r Tetr | ≈37-kb insert in pGAT400ΔBglII | This study |

| pGV29 | Apr | 4-kb fragment of BTF-37 cloned in pBR322 | This study |

| pGV38 | Apr | 8-kb fragment of BTF-37 cloned in pBR322 | This study |

| pBR322 | Apr Tetr | Cloning vector | 15 |

| pBR328 | Apr | Cloning vector | 15 |

| R751 | Tmpr | E. coli broad-host-range R plasmid | 39 |

| RK231 | Kmr | E. coli broad-host-range R plasmid | 23 |

Tra+ and Tra−, transfer proficiency or deficiency, respectively. Tet, anaerobic tetracycline resistance; TetX*, aerobic tetracycline resistance; Rif, rifampin; Trs, trospectomycin; Sm, streptomycin; Sp, spectinomycin; Ap, ampicillin; Cln, clindamycin; Km, kanamycin; Tmp, trimethoprim. All antibiotics were used at concentrations described in Materials and Methods.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA was prepared by the miniprep alkaline lysis method (5) or by affinity purification (Qiagen Corp., Chatsworth, Calif.). All restriction endonucleases and DNA ligase were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). DNA sequencing of BTF-37 subclones was performed using an ABI377 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Conjugation experiments.

Quantitative Bacteroides sp.-to-E. coli and E. coli-to-E. coli filter matings were performed as previously described (63). For Bacteroides sp.-to-E. coli matings, transfer-deficient shuttle plasmid pGAT400ΔBglII was introduced from E. coli HB101 into B. fragilis strain LV23 and the resulting strain was used as a donor in conjugation experiments involving an E. coli HB101 recipient. Transconjugants were selected on ampicillin and streptomycin. For E. coli-to-E. coli matings, mobilization of plasmids from HB101 to DW1030 was routinely assayed in the presence of R751, which provides the mating apparatus. R751 was not used when a plasmid was being tested for autonomous transfer. DW1030 transconjugants were selected on ampicillin and spectinomycin. Mobilization frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of Mob+ plasmid transconjugants by the number of R751 transconjugants (or donors, if R751 was not used) in the same experiment.

Quantitative Bacteroides sp.-to-Bacteroides sp. filter matings were initially performed to capture DNA fragments from Bacteroides spp. and subsequently to test BTF-37-harboring transconjugants. BTF-37 was isolated when capture vector pGAT400ΔBglII was introduced into B. fragilis clinical isolate LV23. A stationary-phase culture of this donor was used to inoculate fresh medium at a 1:50 dilution under anaerobic conditions. Subcultures were induced with 1 μg of tetracycline/ml after 1.25 h. Following a further 5 h of growth (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 1.1), donors (2.5 ml) were washed with 2.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 8 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 145 mM NaCl, pH 6.9) and mixed with 2.5 ml of a culture of a suitable recipient strain (B. fragilis TM4000 or Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron BT4001, also grown to an OD600 of 1.1). Cells were transferred by vacuum aspiration onto 0.45-μm-pore-size Nalgene filters, aseptically transferred to BHIS agar plates, and incubated anaerobically for 16 h. Following incubation, filters were placed in 5 ml of PBS and vortexed to loosen cells and suitable dilutions were plated on selective media (clindamycin, tetracycline, and rifampin). For the data in Fig. 1, subcultures were used in mating experiments 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 h postinduction. Conjugation frequency was calculated by dividing the number of transconjugants obtained by the total number of donor cells. BTF-37-harboring transconjugants were further tested for transfer proficiency by using them as donors and B. fragilis TM429 or E. coli HB101 as the recipient and selecting for trospectomycin- or ampicillin-resistant transconjugants, respectively.

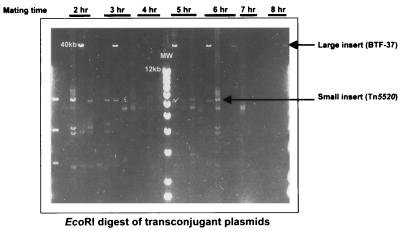

FIG. 1.

Isolation of large DNA fragment insertions in pGAT400ΔBglII from B. fragilis LV23. Restriction enzyme analysis of transconjugant plasmid DNA from matings was performed. Large fragments and those corresponding to Tn5520 are indicated (arrows), along with the time point during growth at which they were isolated. All transconjugant DNA was digested with EcoRI. DNA molecular size markers (MW) are indicated.

Analysis of transconjugant DNA.

Transconjugant plasmid DNA was prepared by the alkaline lysis method of Birnboim and Doly (5) and checked by restriction enzyme analysis with pGAT400ΔBglII digested in a similar manner.

Subcloning and sequencing of BTF-37.

BTF-37 was digested to completion with restriction enzyme Sau3AI. Restriction fragments were ligated to cloning vector pBR322, which had been previously digested with BamHI. Ligation products were transformed to E. coli JM109, and transformants were selected for ampicillin resistance. Six subclones with insert sizes varying from 1 to 8 kb were obtained. Four- and 8-kb subclones were randomly chosen for DNA sequencing, which was initiated using oligonucleotides flanking the BamHI site of pBR322 (forward, 5′-TTCTCGGAGCACTGTCCGACC-3′; reverse, 5′-TCGGTGATGTCGGCGATATAGG-3;). As DNA sequences were obtained from the subclones, new primers were designed to “walk out” from the previous sequence.

Colony hybridizations.

The presence of Tn5520 in BTF-37 was assessed using colony blot hybridization. An internal 3-kb DdeI restriction fragment of Tn5520 was used to generate the probe. The fragment was labeled with psoralen-biotin in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). BTF-37-harboring transconjugants, along with appropriate control strains, were spotted onto charged, sterile nylon membranes. Membranes were transferred to BHIS-agar plates and incubated anaerobically until colonies 1 to 2 mm in diameter were visible. Colonies were lysed, and nucleic acids were fixed on the membranes according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Schleicher & Schuell). Hybridization with the probe was performed for 16 h at 65°C. Chemiluminescence detection with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase was used to visualize hybridization signals.

EM.

Bacteroides spp. and E. coli strains were prepared for electron microscopy (EM) in the same manner as that used to set up conjugation experiments. Briefly, 200 μl of a saturated culture was used to inoculate 10 ml of fresh BHIS. At 1.5 h postinoculation, tetracycline hydrochloride was added to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml (subinhibitory) to induce the cells (only strains that were Tetr were induced). Cells were grown for a further 4.5 h, until the OD600 of the culture was ≈1.1. Then 2.5 ml of this culture was vacuumed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size Nalgene filter, which was then incubated anaerobically for 4 or 6 h on a BHIS agar plate. Following incubations, filters were removed from agar plates, and placed in sterile empty petri dishes. A small piece of each filter (1 cm2) was excised with a sterile scalpel and transferred to a sterile glass vial. Four percent glutaraldehyde was added to just cover the filter surface. After 5 min, excess 4% glutaraldehyde was added to completely soak the filters. Fixed samples were subjected to a standard protocol for scanning or transmission EM preparation (8, 9, 21, 37). Briefly, for scanning EM, the samples were glued to the scanning EM stub, washed with PBS, and subjected to postfixation with 1% osmium tetroxide. This was followed by more PBS washes and a gradient alcohol series (30, 70, and 90%; 20 min each), ending with three washes in 100% ethanol. After a further three washes in hexamethyldisilazane, the samples were dried to the critical point. A dab of silver paint was then added to the edge of the filter, followed by a 2-min silver-palladium sputter coat for scanning EM. Samples were visualized using a JEOL 840A scanning electron microscope or a Hitachi H-600 transmission electron microscope attached to a computer for digital capture of images. All scanning and transmission EM samples were viewed at an acceleration of 15 kV and a probe current of 9 V and at magnifications ranging from ×25,000 to ×60,000.

Digital imaging.

Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels were photographed under UV light. Polaroid prints were scanned at high resolution (1,000 dots per inch [dpi]) using a ScanJet 4c flatbed scanner (Hewlett-Packard, Louisville, Ky.). Scanned graphics files were imported into the application Microsoft PowerPoint and text, and labels were added. Images were printed at high resolution (1,440 dpi) on an Stylus Color 1520 printer (Epson America, Inc., Torrance, Calif.) using heavyweight satin-gloss photographic paper (Hewlett-Packard).

RESULTS

Isolation of BTF-37.

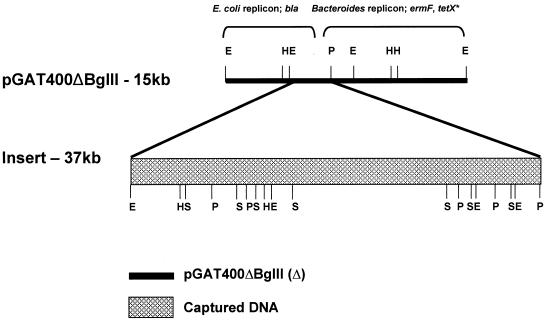

BTF-37 was isolated in a Bacteroides-to-Bacteroides filter mating using nonmobilizable shuttle vector pGAT400ΔBglII. pGAT400ΔBglII (which carries markers for clindamycin, ampicillin, and aerobic tetracycline resistance) was introduced into B. fragilis clinical isolate LV23 by conjugation from E. coli HB101(pRK231) (63). pGAT400ΔBglII contains the pRK231 oriT region, which allows it to be mobilized in trans by pRK231 mobilization proteins, and uses the pRK231 transfer apparatus to transfer to the Bacteroides recipient. Once present in Bacteroides, pGAT400ΔBglII cannot be transferred unless it acquires DNA in cis that harbors oriT and a mobilization gene(s). This property has previously been used to successfully isolate other transfer factors (43, 63). B. fragilis LV23 carrying pGAT400ΔBglII was induced by pretreatment of donor cells with 1 μg of tetracycline/ml and mated with either B. fragilis TM4000 or B. thetaiotaomicron BT4001 as the recipient. Both recipients are devoid of Tet elements or other known transfer factors. Transconjugants were selected on tetracycline to maximize the chances of recovering anaerobic tetracycline resistance and clindamycin resistance. Table 2 shows the transfer frequencies of tetracycline- and clindamycin-resistant transconjugants. Restriction enzyme analysis of independently isolated transconjugant plasmid DNA (Fig. 1) revealed that large and small DNA insertions had occurred in pGAT400ΔBglII. Though the restriction patterns varied among the different independent transconjugants and between matings, the size of the large DNA insert was always approximately 37 kb. The size of the small DNA insert was always approximately 5 kb, and the restriction pattern corresponded to that of previously characterized mobilizable transposon Tn5520 (63). In addition, mating experiments were performed at different stages of growth of the donor to determine whether the size of the insert was growth dependent and whether Tn5520 or the large insert would be isolated preferentially at early, logarithmic, or stationary growth phase. It was noted that large inserts were captured in pGAT400ΔBglII irrespective of the growth phase of the culture. The newly acquired 37-kb DNA in pGAT400ΔBglII for one of the transconjugants (BTF-37) was mapped using restriction analysis (Fig. 2). The insertion occurred in the 3.5-kb EcoRI-PstI fragment of pGAT400ΔBglII and interrupted the pRK231 oriT region. The rest of the capture vector appeared to be unaltered. The size of BTF-37 was calculated to be approximately 50 kb, with insert DNA accounting for approximately 37 kb. This new plasmid was confirmed to express resistance to tetracycline and clindamycin under anaerobic conditions and to tetracycline and ampicillin under aerobic conditions. This indicated that an anaerobic tetracycline resistance phenotype had been acquired and that the tetX*, bla, and ermF genes of pGAT400ΔBglII had been retained.

TABLE 2.

Isolation and transfer characteristics of BTF-37

| Mating type | Donor | Recipient | Frequencya |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | B. fragilis TM4000 | B. fragilis TM429 | 0 |

| B. fragilis TM4000(Tn5520) | B. fragilis TM429 | 0 | |

| B. thetaiotaomicron BT4001(pGAT400ΔBglII) | B. fragilis TM429 | 0 | |

| B. thetaiotaomicron BT4001(Tn5520) | B. fragilis TM429 | 0 | |

| B. fragilis TM4000(Tn5520) | E. coli HB101 | 0 | |

| B. thetaiotaomicron BT4001(pGAT400ΔBglII) | E. coli HB101 | 0 | |

| E. coli HB101(pBR328) | E. coli DW1030 | 0 | |

| Positive control | B. fragilis TM4.23(Tn5520) | B. fragilis TM429 | 2.9 × 10−5 |

| B. fragilis TM4.23(Tn5520) | E. coli HB101 | 1.6 × 10−2 | |

| E. coli HB101(R751 + Tn5520) | E. coli DW1030 | 4.5 × 10−1 | |

| BTF-37 isolation in Bacteroides spp. | B. fragilis LV23 | B. fragilis TM4000 | 3.9 × 10−4 |

| B. fragilis LV23 | B. thetaiotaomicron BT4001 | 1.4 × 10−6 | |

| BTF-37 self-transfers within Bacteroides spp. | B. fragilis TM4000(BTF-37) | B. fragilis TM429 | 1.8 × 10−6 |

| B. thetaiotaomicron BT4001(BTF-37) | B. fragilis TM429 | 1.3 × 10−7 | |

| BTF-37 self-transfers from Bacteroides sp. to E. coli | B. fragilis TM4000(BTF-37) | E. coli HB101 | 1.4 × 10−6 |

| B. thetaiotaomicron BT4001(BTF-37) | E. coli HB101 | 1.8 × 10−6 | |

| BTF-37 self-transfers within E. coli | E. coli HB101(BTF-37) | E. coli DW1030 | 4.5 × 10−7 |

Mating frequencies were calculated relative to the number of donors. For matings where R751 provided the mating apparatus, final conjugation frequency was normalized to R751 transfer frequencies. All matings were performed at least in triplicate, and average frequencies are reported. Transconjugant plasmid DNA was analyzed from every mating to ensure that there were no alterations in test plasmids.

FIG. 2.

Restriction map of BTF-37. Insertion into pGAT400ΔBglII occurred at pRK231 oriT in the 3.5-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment. E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, Sau3AI.

BTF-37 transfers within Bacteroides spp. and to E. coli.

The transfer properties of BTF-37 within different Bacteroides species were assessed using conjugation experiments. BTF-37-harboring TM4000 or BT4001 transconjugants were used as donors in mating experiments with tetracycline-sensitive B. fragilis recipient TM429. TM4000 and BT4001 themselves are devoid of transfer factors and do not facilitate transfer. As a positive control, we assessed the transfer of previously characterized mobilizable transposon Tn5520 (captured in pGAT400ΔBglII) from Tet element-containing strain TM4.23 (63). It was observed that BTF-37 required tetracycline induction and transferred efficiently from TM4000 to TM429 (1.8 × 10−6) and that this frequency was only slightly lower than that for the positive control, Tn5520 (2.9 × 10−5; Table 2). The frequency of transfer from BT4001 was somewhat lower but reproducible (1.3 × 10−7). Transconjugant DNA from the matings was subjected to restriction enzyme analysis (data not shown) to confirm that BTF-37 was unaltered.

We also tested TM4000 and BT4001 harboring BTF-37 as donors in mating experiments with E. coli HB101 to assess if BTF-37 was capable of self-transfer from Bacteroides spp. to E. coli. The transfer of Tn5520 from Tet element-containing B. fragilis strain TM4.23 was used as a positive control, as described above. We observed that, upon tetracycline induction, BTF-37 transferred from both TM4000 and BT4001 to HB101 at frequencies of 1.4 × 10−6 and 1.8 × 10−6, respectively (Table 2). The presence of intact BTF-37 in the HB101 transconjugants was confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis (not shown).

BTF-37 transfers within E. coli.

One HB101(BTF-37) transconjugant, obtained from the mating described previously, was tested for its ability to transfer itself to E. coli recipient DW1030. HB101(R751) was used as a positive control for self-transfer. BTF-37 transferred itself (without a helper plasmid and without tetracycline induction) within E. coli at a lower, but reproducibly detectable, frequency (4.5 × 10−7) than the positive control, R751. A total of three matings gave similar results. A mating experiment using HB101 transformed with BTF-37 plasmid DNA resulted in similar transfer frequencies. In contrast, no transfer from the negative control, HB101(pBR328), was seen. DW1030(BTF-37) transconjugants were subjected to restriction enzyme analysis to demonstrate that BTF-37 was unaltered following transfer to the recipient (not shown).

Tn5520 is linked to BTF-37.

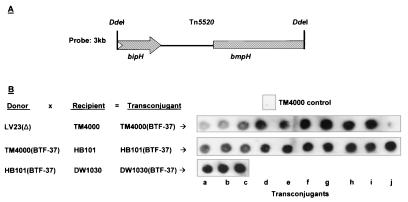

We have previously described the isolation and characterization of B. fragilis mobilizable transposon Tn5520 (63). Since the B. fragilis host strain used for BTF-37 isolation, LV23, was the same as that used to recover Tn5520 and since the small inserts captured in some transconjugants corresponded to Tn5520 (see “Isolation of BTF-37” above), we investigated whether Tn5520 was linked with large-fragment acquisitions by pGAT400ΔBglII. We probed B. fragilis TM4000(BTF-37), E. coli HB101(BTF-37), and E. coli DW1030(BTF-37) by colony hybridization using a Tn5520-specific probe to determine if Tn5520 was present in, and transferred with, BTF-37. Figure 3 demonstrates that Tn5520 is part of all BTF-37-harboring bacterial colonies tested and is retained during transfer within and from Bacteroides spp. (23 transconjugants tested). The presence of Tn5520 was also confirmed by PCR amplification of internal fragments of the Tn5520 bipH (transposase) and bmpH (mobilization) genes for eight transconjugants (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Tn5520 is linked to BTF-37. Matings were performed using B. fragilis LV23, B. thetaiotaomicron, or E. coli HB101, all harboring BTF-37 as the donor, and B. fragilis TM4000, E. coli HB101, or E. coli DW1030 as the recipient. (A) A 3-kb Tn5520-specific DdeI fragment that included the bipH (transposase) and bmpH (mobilization) genes was used as a probe for colony hybridizations of total transconjugant DNA. (B) Ten transconjugants from each mating (a to j) were tested, except for the E. coli-to-E. coli matings, where 3 transconjugants were tested. An example of a negative control (TM4000) is shown. BT4001 and the E. coli strains alone showed no hybridization signal with the probe (not shown).

BTF-37-harboring cells express pilus-like cell-surface structures in Bacteroides spp. and E. coli.

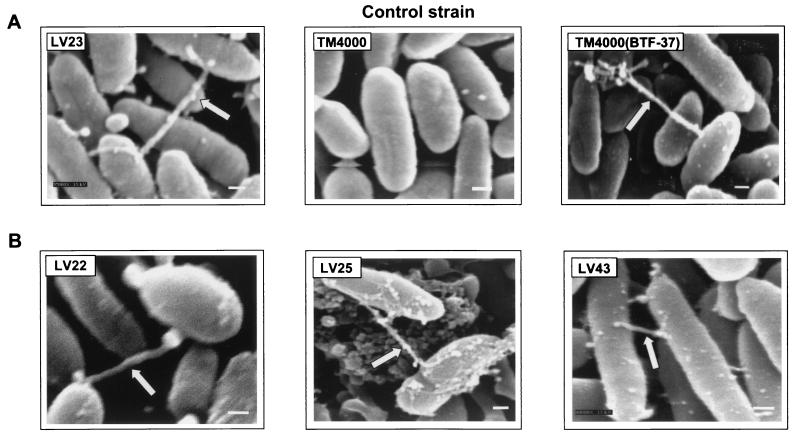

Members of many bacterial genera encode conjugation-specific cell surface structures, notably pili. Based on our previous observation that BTF-37 was self-transferable in Bacteroides spp. and E. coli, we visualized BTF-37-harboring cells using scanning and transmission EM to determine if any surface structures resembling those involved in conjugation in other bacteria might be present. Bacteroides and E. coli strains containing BTF-37 were compared with three Tet element-containing strains, as well as control strain TM4000, which is devoid of Tet elements. Under mating conditions (i.e., tetracycline induction; 6 h on mating filters), but in the absence of recipients, approximately 10 to 15% of LV23, as well as TM4000(BTF-37), expressed tubular pilus-like surface structures (Fig. 4A). The structures were approximately 25 to 50 nm in external diameter and always appeared to be attached to neighboring cells. In contrast to LV23 and other cells harboring BTF-37, Tet element-lacking, transfer-deficient strain TM4000 did not express observable surface structures. Three unrelated Tet element-containing clinical isolates were also studied (LV22, LV25, and LV43) and were found to express structures similar to the ones observed for LV23 and BTF-37-harboring strains (Fig. 4B). These results were further confirmed using transmission EM for TM4000(BTF-37) (Fig. 5), demonstrating that a cell surface structure was present. The expression of the pilus-like structures in LV23 and TM4000(BTF-37) was seen to occur only upon tetracycline induction (Fig. 6A). When cells were visualized at earlier mating time points (4 versus 6 h), many shorter “spikes” were seen radiating from the cell surfaces, occasionally in attachment to other cells. At the later mating time point (6 h), these spikes were replaced with the single longer pilus-like structure (Fig. 6B and C). Similar to what was found for BTF-37, this expression of surface structures at the shorter time point also occurred only under conditions of tetracycline induction.

FIG. 4.

Detection of cell surface structures using scanning EM. All strains were subjected to tetracycline induction and 6 h of incubation on mating filters (see Materials and Methods). (A) Clinical isolate LV23, wild-type control TM4000, and TM4000 harboring BTF-37. Arrows, pilus-like structures. (B) Other Tet element-containing strains. Magnification, ×37,000 to 43,000. All samples were viewed at 15 kV. Panels are representative of visualization of at least 1,000 cells for each sample and of 8 to 10 fields photographed. Approximately 10 to 15% of cells express the surface structure. Bars, 200 nm.

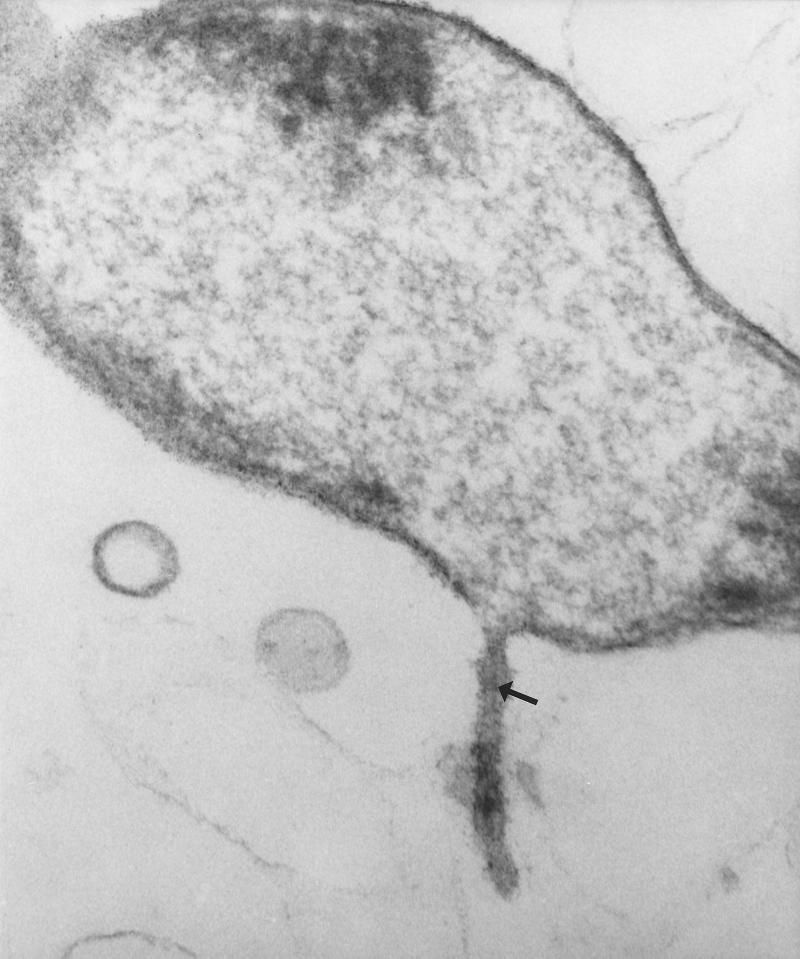

FIG. 5.

Transmission electron micrograph of TM4000(BTF-37). A possible central channel in the pilus-like structure can be seen. The panel is representative of at least 2,000 cells visualized for the sample and of six fields photographed. Approximately 1% of cells visualized express the cell surface structure. Magnification (after size correction of the image), ×54,000.

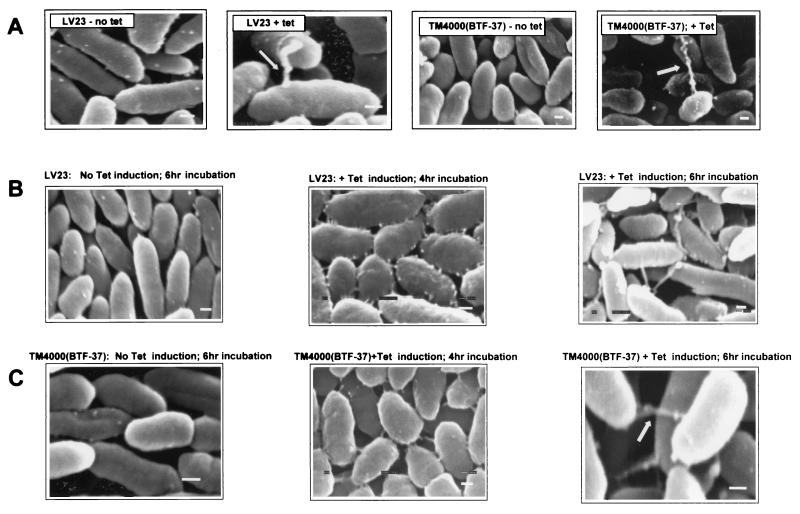

FIG. 6.

(A) Cell surface structures are expressed upon tetracycline induction of LV23 and TM4000(BTF-37). (B and C) Lengths of cell-surface structures vary depending on total time on mating filters. Similar results were obtained for LV23 and TM4000(BTF-37). Magnification, ×37,000 to 43,000. All samples were viewed at 15 kV. Panels are representative of visualization of at least 1,000 cells for each sample and of 8 to 10 fields photographed. Bars, 200 nm. Arrows, pilus-like structures.

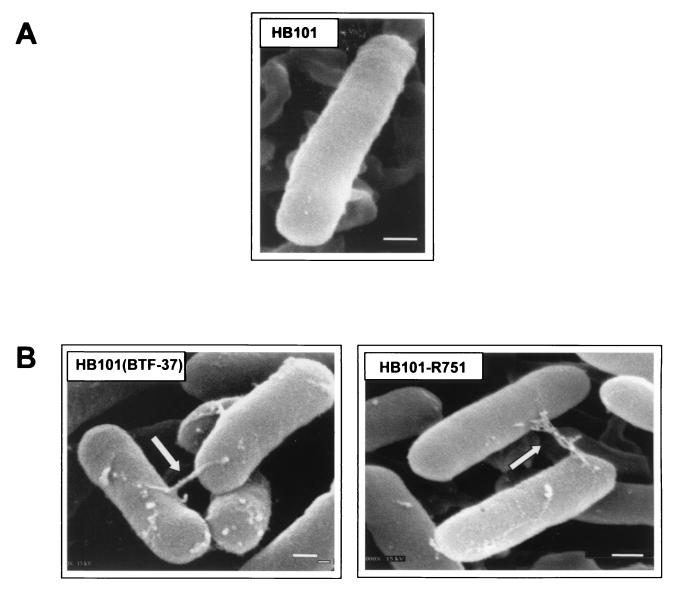

E. coli HB101 containing BTF-37 also expressed tubular structures morphologically similar to those encoded by the Bacteroides sp. strains and E. coli broad-host-range plasmids R751 (Fig. 7) and RK231 (not shown). Tetracycline pretreatment did not affect expression of these structures in E. coli. No pilus-like structures on E. coli HB101 alone were visualized.

FIG. 7.

E. coli HB101 harboring BTF-37 expresses pilus-like cell surface structures. (A) HB101, no plasmid. (B) HB101(BTF-37) and HB101(R751) (self-transferable R plasmid) as a control. Arrows, pilus-like structures. Magnification, ×37,000 to 43,000. All samples were viewed at 15 kV. Panels are representative of visualization of at least 1,000 cells for each sample and of 8 to 10 fields photographed. Bar, 200 nm.

Partial DNA sequencing of BTF-37.

BTF-37 was subcloned in E. coli cloning vector pBR322 as Sau3AI fragments. Four- and 8-kb subclones were randomly picked to initiate DNA sequencing of BTF-37. Analyses of initial sequencing data from these subclones revealed that the tetQ and rteA genes were present, along with ORFs whose predicted translation products showed similarity to the Bacteroides vulgatus Tn4555 TnpA transposase (8-kb subclone; 28% identity and 47% similarity over 172 amino acids), B. vulgatus mobilizable plasmid pIP417 product RepA (8-kb subclone; 27% identity and 48% similarity over 147 amino acids), and the EcoE/A restriction enzyme (4-kb subclone; 43% identity and 62% similarity over 171 amino acids). In addition, an almost complete copy of B. fragilis insertion sequence IS4351 (1.1 kb) was identified on the 8-kb subclone downstream of the tnpA homolog.

DISCUSSION

We have described a new transfer factor, BTF-37, from B. fragilis LV23 that is self-transferable in both Bacteroides spp. and E. coli. This discovery, along with DNA sequence information revealing the presence of tetQ and rteA on BTF-37, strongly suggests that BTF-37 harbors all or a major part of a new Tet element that harbors conjugation-related genes. This transfer factor appears novel, since the available sequence data from BTF-37 (with the exception of tetQ and rteA), do not show similarity to Tet element sequences in the GenBank database. If BTF-37 is a new, complete Tet element, it would be considerably smaller (≈37 kb) than other reported Tet elements (70 to 150 kb [48, 50]). Given its smaller size and self-transferable phenotype, an important question that remains is whether a complete mating apparatus can be encoded by 35 to 40 kb of DNA. Other non-Bacteroides transfer factors such as F and A. tumefaciens Ti plasmids encode conjugation machinery with 15 to 35 kb of DNA (2, 12, 19). Gram-positive conjugative transposons such as Tn916 and Tn1525 are also considered self-transferable and are only 18 and 25 kb in size, respectively (14), suggesting that mating apparatus-encoding regions from different transfer factors may vary in size. In addition, Li et al. identified a 16-kb region from the cTnDOT element that is required and sufficient for transfer from Bacteroides spp. to E. coli (33). However, the self-transfer of this construct in E. coli was has not been reported.

It is of interest that BTF-37 self-transfers in E. coli, since to our knowledge, this is the first report of a Bacteroides sp. conjugal element that is self-transferable in a different bacterial genus. Such transfer has broad implications for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance determinants, especially since Bacteroides spp. are considered to be reservoirs of multiple transfer factors (48, 49; Salyers, letter). We observed autonomous transfer of BTF-37 from Bacteroides to Bacteroides, from Bacteroides to E. coli, and from E. coli to E. coli. In all instances, we were able to recover intact BTF-37 from transconjugant strains, indicating that BTF-37 integrity was maintained during the transfer process, even within a different bacterial genus. Tetracycline induction was required for transfer within, and from, Bacteroides despite the plasmid-borne nature of the rte genes. This indicates that plasmid copy number controlled by the Bacteroides replicon on BTF-37 is at a level that does not interfere with rte gene regulation. Tetracycline induction was, however, not required for BTF-37 transfer within E. coli, possibly due to alterations in rte gene regulation. Transfer from B. fragilis LV23 or TM4000 to Bacteroides sp. or E. coli recipients occurred at the highest frequencies. Transfer from B. thetaiotaomicron and transfer within E. coli occurred at 10- to 100-fold-lower frequencies, and these lower frequencies may have been a result of species variations, donor-encoded factors that negatively affected transfer, or the copy number of BTF-37.

Another finding was that Tn5520 appeared to be linked to BTF-37, indicating a potential role for Tn5520 in BTF-37 transfer. This was demonstrated by colony hybridization revealing that Tn5520 was coisolated in BTF-37 insertions and also by PCR (not shown). This linkage was identified in all Bacteroides sp. and E. coli transconjugants tested. In addition, Tn5520 can be captured alone in pGAT400ΔBglII as we have reported (63) and as was observed in this study (Fig. 1). It is therefore possible that Tn5520 is present as part of BTF-37 in the LV23 chromosome but may independently transpose into pGAT400ΔBglII. Overall, the frequencies of both types of insertions into pGAT400ΔBglII were equal, resulting in some transconjugants harboring the smaller Tn5520 and some harboring the larger BTF-37. It is not known whether Tn5520 is necessary for the transfer of BTF-37, but it could be required for the excision or integration of the 37-kb fragment, for mobilization of the BTF-37 plasmid, or both. Information about the mobilization region of other Tet elements is available only for cTnDOT, where a 1.4-kb DNA fragment was identified and was presumed to harbor the oriT and mob genes (33). However, no sequence information for this mobilization region was reported.

We performed a scanning and transmission EM visualization of BTF-37-harboring and other cells to determine if Bacteroides sp. strains underwent any cell surface alterations during the mating process. This study was undertaken since, to our knowledge, no EM information for any anaerobic bacteria under conjugation conditions exists. Four major observations were made as a result of the EM visualization. First, Tet element-containing strains expressed tubular, pilus-like cell surface structures. In contrast, TM4000, a Bacteroides strain devoid of Tet elements and transfer potential, did not possess similar structures. The structures were approximately 25 to 50 nm in thickness, varied in length, and were expressed by approximately 10 to 15% of the cells viewed under microscopy. They appeared thick and flexible and were observed to be attached even though single strains (i.e., only donors) were used under mating conditions, and not mating pairs. Thus, these structures may have a potential attachment or “sensory” role. Further, upon the use of transmission EM, we observed that approximately 1% of Tet element- and BTF-37-containing cells expressed a cell surface structure that appeared to have a central channel running through the length of the appendage. This is reminiscent of the A. tumefaciens T pilus, which has been reported to have a 2-nm lumen (27). A review of the literature reveals that many different pilus types involved in different processes are present in bacteria (10, 12, 30, 46). Among conjugative pilus types, F pili are 8.5 to 9 nm thick and are involved in attachment of two cells (3, 18, 64). Retraction of F pili brings cells in juxtaposition with each other and facilitates other conjugative processes, such as determination of surface and/or entry exclusion. A. tumefaciens pili are 10 nm thick and are involved in DNA transfer (12. 13). In contrast, conjugation-specific pili of a variety of other bacteria vary greatly, and multiple pilus types are sometimes encoded by the same bacterium and are involved in different aspects of the conjugation process. IncI1 plasmid R64 encodes two pili, a thick pilus required for liquid and solid surface mating and a thin pilus required for liquid matings (28, 67). Pili encoded by the IncB, -K, and -Z plasmids are involved in transfer on solid agar (thick pili) and, in some cases, only cell-cell stabilization (thin pili [8]). Although conjugative pili may vary morphologically, they are invariably associated with an attachment function. Once cell-cell contact has been established, other conjugation-specific systems determine if the recipient is suitable. If the recipient is unsuitable, donor-encoded surface and entry exclusion systems ensure that the mating pair is destabilized. Thus, though initial attachment functions may bring an unsuitable donor and recipient into contact with each other, other functions will ensure that DNA transfer does not occur. This may explain why cells of the same strain are attached via the pilus-like structures in our scanning EM visualizations. These BTF-37-encoded cell surface structures were larger in diameter than those reported for conjugation pili and were reminiscent of attachment fibrils reported for Myxococcus xanthus (4) and bundle-forming pili of enteropathogenic E. coli (approximately 100 nm in diameter [29]), making it likely that they are involved in attachment. The exact physical and biochemical natures of these structures (as well as the involvement of other macromolecules such as polysaccharides) remain to be determined.

The second major observation from the microscopy study was that the cell surface structures were expressed only upon tetracycline induction from the five Tet element-containing strains tested. Interestingly, this tetracycline-dependent expression was also observed for the non-Tet element-containing, transfer-deficient control strain B. fragilis TM4000 when BTF-37 was present. This suggests that the genetic elements responsive to tetracycline are located on BTF-37, as well as the surface structure-encoding gene(s). The presence of rteA on BTF-37 provides strong evidence that tetracycline responsiveness, similar to that observed in the cTnDOT element (33, 57), occurs in BTF-37. It is also quite possible that the cell surface structures are expressed as a result of downstream effects of rte gene product expression, since increases in transfer frequency as well as pilus expression occur with tetracycline induction. This is the first time that tetracycline induction has been associated with the expression of a conjugation-specific surface structure in Bacteroides. These results also make it highly likely that conjugation apparatus-associated structures are harbored on Tet elements (speculated [50], but not shown) and suggest that we have captured a Tet element-like factor that encodes these structures. These results should facilitate the study of the mating apparatus in Bacteroides.

The third major observation was that the cell surface structures appeared to vary in morphology and size depending on the length of time of the mating experiment. When Bacteroides sp. cells were placed on mating filters for 4 h, the structures were visualized as shorter spikes radiating out from the cell surface. At this time point, cells did not appear to be in attachment with other cells. However, upon longer incubation on the filters (6 h; also corresponds with maximum transfer efficiencies), cells harbored only one or two long filamentous structures, which were always in attachment with other cells. Variation in pilus length with time has been previously observed, especially in the pathogenic E. coliI (11, 29, 36, 37), where changing pilus lengths are associated with bacterial adherence and aggregation. We speculate that, at the onset of the mating period, Tet element-harboring cells express these pilus-like structures all over the cell surface but that, upon contact with another cell, only those structures involved in attachment remain, while others retract. It is also possible that there is a generalized retraction (19, 38, 58) that pulls cells attached to these structures into close proximity with donor cells.

The fourth major observation was that E. coli HB101 harboring BTF-37 expressed the pilus-like cell surface structures. The importance of this result should be noted since it underscores the promiscuity of BTF-37. Morphologically, the BTF-37-encoded structures in E. coli resembled those expressed by broad-host-range, self-transferable, drug resistance plasmids R751 and RK231 (not shown). R751-containing cells were used for comparison in these studies since all Bacteroides sp. transfer factors tested to date that are mobilized in E. coli do so when R751 is coresident and provides the mating apparatus for transfer (52). (In contrast, Bacteroides sp. transfer factors do not transfer when F is coresident.) The morphological similarity also supports our speculation that the BTF-37-encoded pilus-like structures are likely conjugation specific. In contrast to those in Bacteroides sp. cells, the pilus-like structures in E. coli were produced in the absence of any tetracycline induction. This may be due to the absence of rte gene regulation in E. coli (based on the copy number of the ColE1 replicon in pGAT400ΔBglII; 35 to 40 copies) or other unknown host factors.

We have also obtained the DNA sequence from a portion of BTF-37. BLAST analyses (1) of ≈12 kb of new DNA sequence revealed the presence of multiple ORFs in addition to tetQ and rteA, whose predicted protein products may be involved with transfer factor functions such as replication and mobilization. Of these, three predicted gene products showed strong similarity to the EcoE/EcoA restriction enzyme (42), B. vulgatus mobilizable plasmid pIP417 RepA protein (24), and the B. vulgatus Tn4555 TnpA recombination-targeting protein (60). We also identified an entire copy of B. fragilis insertion sequence IS4351. The ORF with strong homology to tnpA also showed similarity to the tnpC gene of the dnaK operon of Porphyromonas gingivalis (66) and tnpC of Clostridium perfringens mobilizable plasmid Tn4451 (16). By comparison with available databases, it appears that BTF-37 sequences do not match those of other published Tet elements. Perhaps Tet element-like factors such as BTF-37 harbor multiple, different genetic modules involved in integration, excision, mobilization, and transfer apparatus formation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of John McNulty of the Core Imaging Facility of Loyola University, and the superb technical assistance of Linda Fox. We also thank Danuta Wronska and the members of the Biotechnology Laboratory of Northwestern University. We especially acknowledge Thomas Novicki for his initial observation of large fragment insertions in pGAT400ΔBglII and thank the members of our laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by VA Merit Review grant 002 to D.W.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony, K. G., W. A. Klimke, J. Manchak, and L. S. Frost. 1999. Comparison of proteins involved in pilus synthesis and mating pair stabilization from the related plasmids F and R100-1: insights into the mechanism of conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 181:5149–5159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony, K. G., C. Sherburne, R. Sherburne, and L. S. Frost. 1994. The role of the pilus in recipient cell recognition during bacterial conjugation mediated by F-like plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 13:939–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold, J. W., and L. J. Shimkets. 1988. Cell surface properties correlated with cohesion in Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 170:5771–5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1998. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 6.Bates, S., A. M. Cashmore, and B. M. Wilkins. 1998. IncP plasmids are unusually effective in mediating conjugation of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae: involvement of the tra2 mating system. J. Bacteriol. 180:6538–6543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonheyo, G., D. Graham, N. B. Shoemaker, and A. A. Salyers. 2001. Transfer region of a Bacteroides conjugative transposon, CTnDOT. Plasmid 45:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley, D. E. 1984. Characteristics and function of thick and thin conjugative pili determined by transfer-derepressed plasmids of incompatibility groups I1, I2, I5, B, K and Z. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:1489–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley, D. E., and J. Whelan. 1985. Conjugation systems of IncT plasmids. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131:2665–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns, D. L. 1999. Biochemistry of type IV secretion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao, J., A. S. Khan, M. E. Bayer, and D. M. Schifferli. 1995. Ordered translocation of 987P fimbrial subunits through the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:3704–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christie, P. J. 1997. Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-complex transport apparatus: a paradigm for a new family of multifunctional transporters in eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 179:3085–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chumakov, M. I., and I. V. Kurbanova. 1998. Localization of the protein VirB1 involved in contact formation during conjugation among Agrobacterium cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 168:297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clewell, D. B., S. E. Flannagan, and D. D. Jaworski. 1995. Unconstrained bacterial promiscuity: the Tn916-Tn1545 family of conjugative transposons. Trends Microbiol. 3:230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Covarrubias, L., L. Cervantes, A. Covarrubias, X. Soberon, I. Vichido, A. Blanco, Y. M. Kupersztoch-Portnoy, and F. Bolivar. 1981. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. V. Mobilization and coding properties of pBR322 and several deletion derivatives including pBR327 and pBR328. Gene 13:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crellin, P. K., and J. I. Rood. 1998. Tn4551 from Clostridium perfringens is a mobilizable transposon that encodes the functional Mob protein, TnpZ. Mol. Microbiol. 27:631–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figura, N., and M. Valassina. 1999. Helicobacter pylori determinants of pathogenicity. J. Chemother. 11:591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost, L. S., B. B. Finlay, A. Opgenorth, W. Paranchych, and J. S. Lee. 1985. Characterization and sequence analysis of pilin from F-like plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 164:1238–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frost, L. S., K. A. Ippen-Ihler, and R. Skurray. 1994. Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor. Microbiol. Rev. 58:162–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grahn, A. M., J. Haase, D. H. Bamford, and E. Lanka. 2000. Components of the RP4 conjugative transfer apparatus form an envelope structure bridging inner and outer membranes of donor cells: implications for related macromolecule transport systems. J. Bacteriol. 182:1564–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossman, T. H., L. S. Frost, and P. M. Silverman. 1990. Structure and function of conjugative pili: monoclonal antibodies as probes for structural variants of F pili. J. Bacteriol. 172:1174–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guiney, D. G. 1984. Promiscuous transfer of drug resistance in gram-negative bacteria. J. Infect. Dis. 149:320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guiney, D. G., P. Hasegawa, and C. E. Davis. 1984. Plasmid transfer from Escherichia coli to Bacteroides fragilis: differential expression of antibiotic resistance phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7203–7206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haggoud, A., S. Trinh, M. Moumni, and G. Reysset. 1995. Genetic analysis of the minimal replicon of plasmid pIP417 and comparison with the other encoding 5-nitroimidazole resistance plasmids from Bacteroides spp. Plasmid 34:132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hecht, D. W., T. J. Jagielo, and M. H. Malamy. 1991. Conjugal transfer of antibiotic resistance factors in Bacteroides fragilis: the btgA and btgB genes of plasmid pBFTM10 are required for its transfer from Bacteroides fragilis and for its mobilization by IncPb plasmid R751 in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:7471–7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hecht, D. W., and M. H. Malamy. 1989. Tn4399, a conjugal mobilizing transposon of Bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 171:3603–3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kado, C. I. 2000. The role of the T-pilus in horizontal gene transfer and tumorigenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, S. R., and T. Komano. 1997. The plasmid R64 thin pilus identified as a type IV pilus. J. Bacteriol. 179:3594–3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knutton, S., R. K. Shaw, R. P. Anantha, M. S. Donnenberg, and A. A. Zorgani. 1999. The type IV bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli undergoes dramatic alterations in structure associated with bacterial adherence, aggregation and dispersal. Mol. Microbiol. 33:499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuehn, M. J. 1997. Establishing communication via gram-negative bacterial pili. Trends Microbiol. 5:130–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuipers, E. J., D. A. Israel, J. G. Kusters, and M. J. Blaser. 1998. Evidence for a conjugation-like mechanism of DNA transfer in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 180:2901–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanka, E., and B. M. Wilkins. 1995. DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. J. Biochem. 64:141–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, L. Y., N. B. Shoemaker, and A. A. Salyers. 1995. Location and characteristics of the transfer region of a Bacteroides conjugative transposon and regulation of transfer genes. J. Bacteriol. 177:4992–4999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, P. L., D. M. Everhart, and S. K. Farrand. 1998. Genetic and sequence analysis of the pTiC58 trb locus, encoding a mating-pair formation system related to members of the type IV secretion family. J. Bacteriol. 180:6164–6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, P. L., I. Hwang, H. Miyagi, H. True, and S. K. Farrand. 1999. Essential components of the Ti plasmid trb system, a type IV macromolecular transporter. J. Bacteriol. 181:5033–5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowe, M. A., S. C. Holt, and B. I. Eisenstein. 1987. Immunoelectron microscopic analysis of elongation of type 1 fimbriae in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maher, D., R. Sherburne, and D. E. Taylor. 1993. H-pilus assembly kinetics determined by electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 175:2175–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malmborg, A. C., E. Soderlind, L. Frost, and C. A. Borrebaeck. 1997. Selective phage infection mediated by epitope expression on F pilus. J. Mol. Biol. 273:544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer, R. J., and J. A. Shapiro. 1980. Genetic organization of the broad-host-range IncP-1 plasmid R751. J. Bacteriol. 143:1362–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy, C. G., and M. H. Malamy. 1993. Characterization of a “mobilization cassette” in transposon Tn4399 from Bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:5814–5823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy, C. G., and M. H. Malamy. 1995. Requirements for strand- and site-specific cleavage within the oriT region of Tn4399, a mobilizing transposon from Bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:3158–3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray, N. E., A. S. Daniel, G. M. Cowan, and P. M. Sharp. 1993. Conservation of motifs within the unusually variable polypeptide sequences of type I restriction and modification enzymes. Mol. Microbiol. 9:133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Novicki, T. J., and D. W. Hecht. 1995. Characterization and DNA sequence of the mobilization region of pLV22a from Bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:4466–4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pansegrau, W., and E. Lanka. 1996. Enzymology of DNA transfer by conjugative mechanisms. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 54:197–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pansegrau, W., and E. Lanka. 1996. Mechanisms of initiation and termination reactions in conjugative DNA processing. J. Biol. Chem. 271:13068–13076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pohlman, R. F., H. D. Genetti, and S. C. Winans. 1994. Common ancestry between IncN conjugal transfer genes and macromolecular export systems of plant and animal pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 14:655–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reyssett, G., A. Haggoud, W.-J. Su, and M. Sebald. 1992. Genetic and molecular analysis of pIP417 and pIP419: Bacteroides plasmids encoding 5-nitroimidazole resistance. Plasmid 27:181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salyers, A. A., and C. F. Amabile-Cuevas. 1997. Why are antibiotic resistance genes so resistant to elimination? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2321–2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salyers, A. A., and N. B. Shoemaker. 1997. Resistance gene transfer in anaerobes: new insights, new problems. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23:S36–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salyers, A. A., N. B. Shoemaker, L. Y. Li, and A. M. Stevens. 1995. Conjugative transposons: an unusual and diverse set of integrated gene transfer elements. Microbiol. Rev. 59:579–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shoemaker, N. B., R. D. Barber, and A. A. Salyers. 1989. Cloning and characterization of a Bacteroides conjugal tetracycline-erythromycin resistance element using a shuttle cosmid vector. J. Bacteriol. 171:1294–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shoemaker, N. B., C. Getty, E. P. Guthrie, and A. A. Salyers. 1986. Regions in Bacteroides plasmids pBFTM10 and pB8-51 that allow Escherichia coli-Bacteroides shuttle vectors to be mobilized by IncP plasmids and by a conjugative Bacteroides tetracycline resistance element. J. Bacteriol. 166:959–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shoemaker, N. B., and A. A. Salyers. 1988. Tetracycline-dependent appearance of plasmid-like forms in Bacteroides uniformis 0061 mediated by conjugal Bacteroides tetracycline resistance elements. J. Bacteriol. 170:1651–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sitailo, L. A., A. M. Zagariya, P. J. Arnold, G. Vedantam, and D. W. Hecht. 1998. The Bacteroides fragilis BtgA mobilization protein binds to the oriT region of pBFTM10. J. Bacteriol. 180:4922–4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith, C. J., and A. C. Parker. 1998. The transfer origin for Bacteroides mobilizable transposon Tn4555 is related to a plasmid family from gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 180:435–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith, C. J., G. D. Tribble, and D. P. Bayley. 1998. Genetic elements of Bacteroides species: a moving story. Plasmid 40:12–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevens, A. M., N. B. Shoemaker, L. Y. Li, and A. A. Salyers. 1993. Tetracycline regulation of genes on Bacteroides conjugative transposons. J. Bacteriol. 175:6134–6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strom, M. S., and S. Lory. 1993. Structure-function and biogenesis of the type IV pili. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:565–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tally, F. P., and M. H. Malamy. 1982. Mechanism of antimicrobial resistance and resistance transfer in anaerobic bacteria. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 35:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tribble, G. D., A. C. Parker, and C. J. Smith. 1999. Transposition genes of the Bacteroides mobilizable transposon Tn4555: role of a novel targeting gene. Mol. Microbiol. 34:385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trinh, S., A. Haggoud, and G. Reyssett. 1996. Conjugal transfer of the 5-nitroimidazole resistant plasmid pIP417 from Bacteroides vulgatus BV-17: characterization and nucleotide sequence analysis of the mobilization region. J. Bacteriol. 178:6671–6676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valentine, P. J., N. B. Shoemaker, and A. A. Salyers. 1988. Mobilization of Bacteroides plasmids by Bacteroides conjugal elements. J. Bacteriol. 170:1319–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vedantam, G., T. J. Novicki, and D. W. Hecht. 1999. Bacteroides fragilis transfer factor Tn5520: the smallest bacterial mobilizable transposon containing single integrase and mobilization genes that function in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:2564–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willets, N. 1993. Bacterial conjugation, p.1–22. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 65.Willets, N., and B. Wilkens. 1984. Processing of plasmid DNA during bacterial conjugation. Microbiol. Rev. 48:24–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoshida, A., Y. Nakano, Y. Yamashita, T. Oho, Y. Shibata, M. Ohishi, and T. Koga. 1999. A novel dnaK operon from Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEBS Lett. 446:287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshida, T., S. R. Kim, and T. Komano. 1999. Twelve pil genes are required for biogenesis of the R64 thin pilus. J. Bacteriol. 181:2038–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]