Abstract

Pseudomonas-derived regulators DmpR and XylR are structurally and mechanistically related ς54-dependent activators that control transcription of genes involved in catabolism of aromatic compounds. The binding of distinct sets of aromatic effectors to these regulatory proteins results in release of a repressive interdomain interaction and consequently allows the activators to promote transcription from their cognate target promoters. The DmpR-controlled Po promoter region and the XylR-controlled Pu promoter region are also similar, although homology is limited to three discrete DNA signatures for binding ς54 RNA polymerase, the integration host factor, and the regulator. These common properties allow cross-regulation of Pu and Po by DmpR and XylR in response to appropriate aromatic effectors. In vivo, transcription of both the DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu regulatory circuits is subject to dominant global regulation, which results in repression of transcription during growth in rich media. Here, we comparatively assess the contribution of (p)ppGpp, the FtsH protease, and a component of an alternative phosphoenolpyruvate-sugar phosphotransferase system, which have been independently implicated in mediating this level of regulation. Further, by exploiting the cross-regulatory abilities of these two circuits, we identify the target component(s) that are intercepted in each case. The results show that (i) contrary to previous speculation, FtsH is not universally required for transcription of ς54-dependent systems; (ii) the two factors found to impact the XylR/Pu regulatory circuit do not intercept the DmpR/Po circuit; and (iii) (p)ppGpp impacts the DmpR/Po system to a greater extent than the XylR/Pu system in both the native Pseudomonas putida and a heterologous Escherichia coli host. The data demonstrate that, despite the similarities of the specific regulatory circuits, the host global regulatory network latches onto and dominates over these specific circuits by exploiting their different properties. The mechanistic implications of how each of the host factors exerts its action are discussed.

Soil microorganisms such as Pseudomonas putida have the ability to aerobically catabolize a wide range of aromatic hydrocarbons via suites of specialized catabolic enzymes (reviewed in references 36 and 72). Operons encoding these catabolic enzymes are frequently found on plasmids or, if located on the chromosome, are often carried on transposons or flanked by insertion sequences, ensuring a degree of transferability (72). The ability to catabolize aromatics is nonessential, serving only to confer an advantage to the host bacterium under conditions where aromatic compounds are readily available. Therefore, retention of these catabolic systems is only truly advantageous if their usefulness does not compromise the host fitness under other conditions. Thus, aromatic catabolic systems have been found to be tightly regulated in response to signals specific to their specialized function and also to be appropriately subservient to the existing evolutionarily adapted host global regulatory network (2, 17, 25, 31, 42, 68). However, the underlying mechanisms and the dominant global regulatory systems involved have only been addressed in a few cases. Among these are the pVI150-borne dmp system of Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600, which mediates conversion of (methyl)phenols to pyruvate and acetyl-coenzyme A (reviewed in reference 54), and the pWW0-borne xyl upper operon, which encodes enzymes for conversion of toluenes and xylenes into benzoate intermediates, which are further transformed by enzymes of the xyl lower (meta) pathway (reviewed in reference 41). Host-imposed regulation is manifested in both systems as repression of transcription during rapid growth in rich media even though the specific activation signal is present (12, 25, 68). Conceptually, the functional outcome is analogous to glucose catabolite repression of the use of alternative sugars such as lactose in enterics, i.e., the silencing of alternative metabolic pathways until preferred nutrients are in short supply (69).

The major regulators of the dmp and xyl systems, DmpR and XylR, control transcription in response to distinct sets of aromatic effector compounds representing pathway substrates and structural analogues (41, 60, 62). The Po promoter is the sole target for DmpR, while XylR controls both the Pu (upper-operon) promoter and one of the promoters of the Ps region controlling transcription of the xylS regulatory gene (41). DmpR and XylR are highly homologous ς54-dependent regulators (35, 60) that have many structural and mechanistic features in common. The N-terminal signal reception domains of the two regulators can be exchanged without affecting common activator function, but this results in a corresponding switching of aromatic effector profiles (62, 65). Furthermore, independent genetic and biochemical studies have led to the conclusion that the two regulators are activated upon aromatic effector binding by similar derepression mechanisms involving release of repressive interdomain interactions that constrain the intrinsic ATPase activity and transcriptional activating property of the regulators (28, 47–49, 52, 62). Conformational changes induced by the released ATPase activities ultimately lead to removal of the repressive effect of ς54 on the DNA-melting potential of the RNA polymerase and thus transcriptional initiation (7, 37, 70).

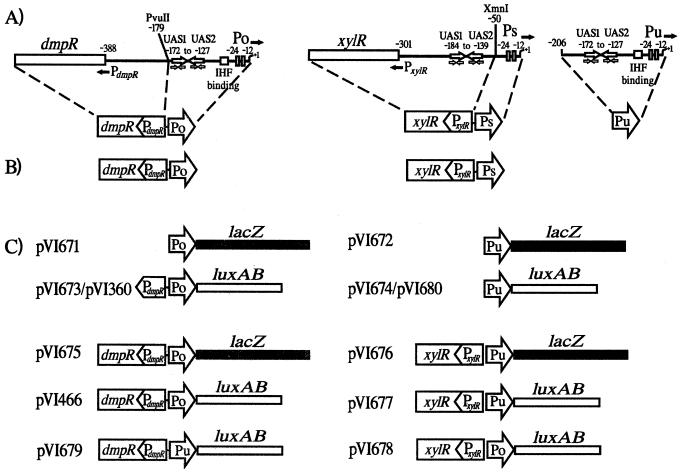

Unlike the DmpR and XylR regulators, which have homology throughout their lengths, the Po and Pu regions have similarities in only three regions. These include the −24, −12 promoter motif recognized by ς54 RNA polymerase (Eς54), an integration host factor (IHF) binding site required for optimal promoter output, and related upstream activating sequences (UAS) for binding the regulators (Fig. 1A) (1, 20, 64, 67). Although the sequences of the Po and Pu promoter regions differ outside these regions, the regulator binding motifs are sufficiently similar to allow DmpR binding to Pu (53). Moreover, DmpR and XylR can efficiently cross-regulate each other’s target promoter in a manner that maintains the dominant physiological control observed in their native systems (29).

FIG. 1.

(A) Regulatory elements of dmp and xyl systems, as described in the text. The dmpR gene is organized in a divergent configuration from its target promoter Po. The xylR gene is similarly orientated relative to Ps, the upstream activating sequences (UASs) of which overlap with the xylR promoter, while its other target promoter, Pu, is located distally on the pWW0 plasmid. Indicated PvuII and XmnI restriction sites were used as working boundaries for PdmpR and PxylR, respectively, in instances where the regulatory genes have to be dissected from their divergently positioned promoters. (B) Schematic representation of the chromosomal inserts in KT2440::dmpR and KT2440::xylR derivatives. (C) Schematic representation of reporter constructs (lacZ and luxAB) used in this study. White boxes and arrows, regulatory elements that originate from the dmp and xyl systems, as indicated.

The minimal components of the dmp and xyl systems needed as targets for host-imposed regulation are, in both cases, the regulator and its cognate promoter (12, 34, 68). Studies aimed at identifying global regulatory systems responsible for host-imposed response to cellular physiology have identified different players. For the DmpR/Po system, a link to cell physiology via stringent response factor (p)ppGpp has been reported (69), while ATP-dependent physiological protease FtsH has been demonstrated to be required for XylR-mediated Pu transcription (8). In addition, ptsN, a component of an alternative phosphoenolpyruvate-sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS), has been reported to be responsible for glucose repression of the XylR/Pu regulatory circuit (11, 14). The similarities of the DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu systems suggest that global players affecting one system might similarly affect the other. In this work we sought to directly compare the effects of the different global factors on the two related aromatic-responsive systems. In particular, we were interested to determine (i) if the two factors (FtsH and PtsN) previously found to impact the XylR/Pu system also interact with the DmpR/Po system and (ii) if the role of alarmone (p)ppGpp, previously analyzed predominantly in Escherichia coli, affects the two systems to the same extent in the native P. putida host. The results show that, despite the similarities in the specific regulation of the dmp and xyl upper operons, their interactions with the host global regulatory network vastly differ. Furthermore, results obtained by dissecting the contributions of regulators and promoters to the different responses provide evidence that global regulatory systems intercept these specific regulatory circuits by predominantly exploiting properties of the regulators.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. The schematics of construction of a series of key dmpR and xylR derivatives used in this study are shown in Fig. 1C. Plasmids were constructed using standard recombinant DNA techniques (57), and DNA generated using the PCR was subjected to sequence analysis. PCR amplification of Po (−233 to +126) and Pu (−205 to +93) promoters as EcoRI-BamHI fragments and subsequent insertion into corresponding sites on the lacZ-carrying pRW2A gave rise to pVI671 and pVI672, respectively. Plasmids pVI673 (Po, −477 to +2) and pVI674 (Pu, −208 to +2) were likewise constructed by insertion of each of the promoter fragments into a derivative of pRK2501-E carrying the luxAB reporter from pVI466. Plasmid pVI675 was derived by replacing the luxAB gene on the BamHI fragment of pVI466 with the lacZ gene on the HindIII fragment of pRW2A with the help of a linker. Replacing the NotI-BamHI dmpR-Po portion of pVI675 with the xylR-Pu portion from pMCP1 subsequently generated plasmid pVI676. Assembly of an HpaI-XmnI-bearing xylR fragment (from pTK19) and a blunt-ended KpnI-HindIII-bearing Pu-luxAB fragment (from pVI674) onto RSF1010-based vector pVI397 generated pVI677. Plasmid pVI678 was constructed in an analogous manner except that a blunt-ended Po-luxAB fragment (PvuII-HindIII from pVI466) was used. Plasmid pVI679 was generated using the same pVI397 vector by assembling the NotI-PvuII dmpR fragment of pVI466 and the EcoRV-HindIII Pu-luxAB fragment of pVI674. RSF1010-based Po-luxAB reporter plasmid pVI360 (Po, −477 to +2) has previously been described (62). Plasmid pVI680 was generated to provide an equivalent Pu-luxAB reporter plasmid and carries Pu (−208 to +2) as a SalI-to-BamHI fragment directly fused to the BamHI luxAB fragment.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmidsa

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. putida strains | ||

| Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600 | Hgr, prototroph, carrying (methyl)phenol catabolic pVI150 | 61 |

| KT2440 (pWW0::Tn401) | Res− prototroph carrying Cbr derivative of TOL pWW0 | M. Bagdasarian |

| KT2440::dmpR-Km, KT2440::dmpR-Tel | Chromosomally located dmpR transcribed from its native promoter | 60, this study |

| KT2440::xylR-Km, KT2440::xylR-Tel | Chromosomally located xylR transcribed from its native promoter | This study, this study |

| PP1-dmpR | KT2440::dmpR-Tel relA::Km spoT::Gm, (p)ppGpp0 | This study |

| PP1-xylR | KT2440::xylR-Tel relA::Km spoT::Gm, (p)ppGpp0 | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| MG1655Δlac | F− λ− K-12 prototroph, ΔlacX74 | This study |

| CF1693Δlac | MG1655 ΔlacX74 ΔrelA251::Km ΔspoT207::Cm | This study |

| A8514 | W3110 [IN(rrnD-rrnE)1] lac | 8 |

| A8926 | W3110 sfhC220::Tn10, ΔftsH3::Km lac | 8 |

| S17λpir | Tpr/Smr/Res− RP4-mob+; λpir lysogen, permissive donor host for R6K-based suicide plasmids | 22 |

| Vectors | ||

| pBluescript SK | Cbr multipurpose cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pGP704-L | Cbr, R6K-based cloning vector | 50 |

| pMMB66EH | Cbr, broad-host-range RSF1010 laclq-Ptac expression vector | 30 |

| pRK2501-E | Tcr Kmr, broad-host-range RK2-based cloning vector | 39 |

| pRW2A | Tcr, broad-host-range RK2-based vector with a promoter-less lacZ gene | 39 |

| p34S-Gm | Gmr gene flanked by restriction sites | 24 |

| p34S-Km3 | Kmr gene flanked by restriction sites | 23 |

| pUTminiTn5-Km2 | Cbr Kmr, mini-Tn5 suicide donor plasmid | 19 |

| pUTminiTn5-Tellurite | Cbr Telr, mini-Tn5 suicide donor plasmid | 58 |

| pV1397 | Cbr, pMMB66EH derivative deleted of lac-Ptac | 62 |

| Expression plasmids | ||

| pMCP1 | Spr Smr, pPS10 derivative carrying xylR-Pu-lacZ | 8 |

| pTK19 | Kmr, RSF1010 based, carrying xylR transcribed from its native promoter | 18 |

| pV1360 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying Po-luxAB | 62 |

| pV1401 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying dmpR transcribed from its native promoter | 62 |

| pV1466 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying dmpR-Po-luxAB | 68 |

| pV1671 | Tcr, RK2 based, Po controlling transcription of lacZ | This study |

| pV1672 | Tcr, RK2 based, Pu controlling transcription of lacZ | This study |

| pV1673 | Tcr, RK2 based, Po controlling transcription of luxAB | This study |

| pV1674 | Tcr, RK2 based, Pu controlling transcription of luxAB | This study |

| pV1675 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying dmpR-Po-lacZ reporter unit | This study |

| pV1676 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying xylR-Pu-lacZ reporter unit | This study |

| pV1677 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying xylR-Pu-luxAB reporter unit | This study |

| pV1678 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying xylR-Po-luxAB reporter unit | This study |

| pV1679 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying dmpR-Pu-luxAB reporter unit | This study |

| pV1680 | Cbr, RSF1010 based, carrying Pu-luxAB reporter unit | This study |

| Suicide plasmids | ||

| pV1681 | Cbr, R6K based, KT2440 relA::Km on pGP704-L | This study |

| pV1682 | Cbr, R6K based, KT2440 spoT::Gm on pGP704-L | This study |

Resistance abbreviations: Cb, carbenicillin; Hg, mercuric chloride; Gm, gentamicin; Km, kanamycin; Sm, streptomycin; Sp, spectinomycin; Tc, tetracycline; Tel, tellurite; Tp, trimethoprim.

DNA fragments carrying antibiotic resistance gene replacement of the relA and spoT homologues of KT2440 were first assembled in pBluescript SK and then subsequently cloned as BamHI-to-XhoI fragments between the BglII and SalI sites of a Pseudomonas suicide replication plasmid (pGP704-L) to generate pVI681 and pVI682. The insert in plasmid pVI681 carries the first 573 bp of the relA coding sequence (codons 1 to 191), followed by the SmaI Km-3 cassette from p34S-Km3, the last 633 bp of the relA coding sequence, and the termination codon. The resulting gene replacement, designated relA::Km, thus has the internal 1,032 bp of KT2440 relA (encoding 344 amino acids of the predicted 746-residue protein) replaced by the Kmr gene. The insert in plasmid pVI682 carries 375 bp of the coding sequence of spoT (codons 5 to 129) followed by the SmaI Gm cassette from p34S-Gm, the last 372 bp of the spoT coding sequence, and the termination codon. The resulting gene replacement, designated spoT::Gm, thus has the internal 1,347 bp of KT2440 spoT (encoding 449 amino acids of the predicted 702-residue protein) replaced by the Gmr gene. In both pVI681 and pVI682, the antibiotic resistance gene is orientated so it is transcribed in the same direction as relA and spoT, respectively.

Chromosomal insertions of dmpR and xylR into P. putida were achieved by cloning the fragment of interest onto pUTminiTn5-Km2 and pUTminiTn5-Tellurite and their subsequent transposition onto the P. putida chromosome, as previously described (60). The xylR gene inserted into P. putida KT2440 originated as an HpaI fragment from pTK19, while the dmpR gene was obtained as a NotI fragment from pVI401. For both dmpR and xylR, KT2440 isolates derived from miniTn5-Km2 or miniTn5-Tellurite insertions promoted indistinguishable transcription from their cognate luxAB reporter plasmids (data not shown). The KT2440-dmpR-Tel and KT2440-xylR-Tel derivatives were chosen as the parents for generation of (p)ppGpp0 derivatives by replacement of the internal portions of relA and spoT by antibiotic resistance genes via homologous recombination as has been previously described in detail (50). The relA::Km derivatives were generated by conjugation of pVI681 from permissive replication host S17λpir on rich solid media. Tellurite and kanamycin were used for selection of first-site recombination, and second-site recombinants were detected by screening for sensitivity to the carbenicillin resistance marker of the donor plasmid. The presence of the mutant gene and absence of a wild-type copy were confirmed by PCR. The resulting strains were then used as the parents in an analogous second round of conjugation using pVI682 harboring spoT::Gm, with kanamycin and gentamicin used as selection for first-site recombination.

E. coli MG1655 and CF1693 derivatives with lac genes deleted were generated by P1 transduction to eliminate background β-galactosidase activity when the lacZ gene was to be used as the reporter. The Δlac strains were analyzed for Po transcriptional profiles using the luxAB reporter and were found to be indistinguishable from their parent strains (data not shown).

Growth and culture conditions.

All strains were grown at 30°C in Luria broth (LB) (57) unless otherwise indicated. Minimal M9 medium (57) was supplemented with 0.2% Casamino Acids, 10 mM glucose, and/or 100 μg of thiamine/ml. Antibiotic concentrations used were as follows: carbenicillin, 100 μg/ml for E. coli and 1 mg/ml for P. putida; gentamicin, 15 μg/ml for E. coli and 100 μg/ml for P. putida; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; tetracycline, 20 μg/ml; potassium tellurite, 40 μg/ml. Aromatic effectors (2-methylphenol for DmpR and 3-methylbenzyl alcohol for XylR) were added to final concentrations of 0.5 mM for E. coli and 2 mM for P. putida.

Before all assays and analyses, cultures were grown overnight in various media containing appropriate antibiotics for plasmid selection. To ensure balanced growth for reporter gene assays, cells from overnight cultures were diluted 1:1,000, grown to exponential phase, and then diluted once more before initiation of the experiment by addition of the relevant aromatics. For Western analyses, overnight cultures were also diluted 1:1,000, but, when they reached exponential phase, effectors were added and growth was allowed to continue for 4 to 5 h before the cells were harvested.

Reporter gene assays.

Activity of the lacZ gene product β-galactosidase was determined spectrophotometrically, using O-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as the substrate, on cells permeabilized with chloroform and sodium dodecyl sulfate, as previously described (44). Luciferase assays of the luxAB gene product were performed on 100 μl of whole cells using a 1:2,000 dilution of decanal, and light emission was measured by a PhL luminometer (Mediator Diagnostics). Data points for both assays are the averages of duplicate determinations, and the assay profiles over growth shown in the figures are representative of at least two independent experiments.

(p)ppGpp assays.

Cells to be assayed for (p)ppGpp were grown in modified low-phosphate MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) media (45) supplemented with 20 mM glucose and all 20 amino acids (69). Aliquots of the parent culture were taken at an optical density at 650 nm of ∼1.0 and were further grown in the presence of 100 μCi of 32P (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech)/ml for 90 min. Cells were then collected by centrifugation, resuspended in ice-cold 1 M formic acid, and treated as described previously (5). Samples were spotted on polyethyleneimine cellulose plates (Merck), fixed by methanol, and dried, and ascending chromatography in 1.5 M KH2PO4 buffer, pH 3.4, was used to separate the nucleotide species.

Western analyses of regulator expression levels.

Crude extracts of cytosolic proteins, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transfer to nitrocellulose filters, and Western blot analysis with polyclonal rabbit anti-DmpR antibodies raised against an A domain-truncated version of DmpR were as described previously (63). Antibody-decorated bands were revealed using Amersham Pharmacia Biotech chemiluminescence reagents as directed by the supplier. The amount of regulator proteins present was estimated by comparing 20 μg of total cytosolic protein against a standard series (0.02- to 2-fmol loadings) of purified His-tagged DmpR (48) and XylRΔA (from V. de Lorenzo) proteins. Several exposures of each series of experiments were performed so that quantification of samples relative to standards was always performed with exposures in the grey scale. The quantification shown in Table 2 makes the assumption that the anti-DmpR sera cross-react with full-length XylR with the same affinity as they do with the XylRΔA standards.

TABLE 2.

Regulator expression levels

| Strain | DmpR test system | DmpR level (pmol/mg of CEa) | XylR test system | XylR level of (pmol/mg of CE) | XylR/DmpR ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native strain | Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600 | 4.4 | KT2440 (pWW0::Tn401) | 45.5 | 10.3 |

| P. putida | KT2440::dmpRb | 9.8 | KT2440::xylRb | 29.3 | 3.0 |

| KT2440::dmpR-Po-luxAB | 4.4 | KT2440::xylR-Pu-luxAB | 26.0 | 5.9 | |

| E. coli | |||||

| MG1655Δlac | pV1466 dmpR-Po-luxAB | 1.0 | pV1677 xylR-Pu-luxAB | 19.5 | 19.5 |

| pVI679 dmpR-Pu-luxAB | 1.0 | pV1678 xylR-Po-luxAB | 19.5 | 19.5 | |

| CF1693Δlac | pVI466 | 1.5 | pVI677 | 13.0 | 10.6 |

| pVI679 | 1.5 | pVI678 | 19.5 | 13.0 | |

| A8514 | pVI466 | 2.0 | pVI677 | 39.0 | 19.5 |

| pVI679 | 2.0 | pVI678 | 42.3 | 21.2 | |

| A8926 | pVI466 | 2.4 | pVI677 | 16.3 | 6.8 |

| pVI679 | 2.4 | pV1678 | 19.5 | 8.1 |

CE, crude extract.

No differences in DmpR and XylR levels in KT2440 derivatives harboring chromosomal copies of dmpR or xylR delivered via miniTn5-Km2 or miniTn5-Tellurite were found. Likewise no differences in DmpR and XylR levels between the (p)ppGpp0 derivatives (PP1::dmpR and PP2::xylR) and the parent strains were observed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu luxAB and lacZ reporter gene transcriptional profiles are similar.

Physiological regulation of both the P. putida-derived DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu minimal systems can be mimicked in E. coli, demonstrating that this heterologous host has functional counterparts to those that mediate global regulation in the native host. This made it reasonable to exploit available E. coli mutant strains in combination with minimal transcriptional reporter systems to identify the host-encoded factors that intercept these specific regulatory circuits (12, 68). In previous studies, the Vibrio harveyi luciferase luxAB gene has consistently been used as a reporter for the DmpR/Po system, whereas β-galactosidase encoded by lacZ has been used for the XylR/Pu system. While this allows trends and gross profiles between the two to be compared, questions of differential sensitivity, reporter half-lives, and other possibly unanticipated variables make finer comparison difficult. To overcome this limitation, corresponding luxAB and lacZ reporters were made for each of the DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu minimal regulatory units (Fig. 1).

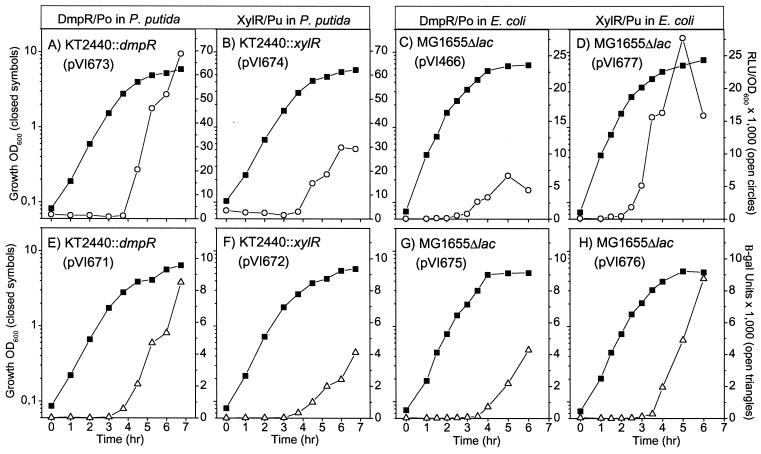

Medium composition has a profound effect on transcription from the Po and Pu promoters. In defined minimal media, an immediate transcriptional response is observed from both promoters upon addition of aromatic effectors. However, addition of components of rich media results in a delay in transcription of several hours (40, 68, 69). In rich media such as LB, DmpR- and XylR-mediated transcription from their cognate promoters is not observed during exponential phase even when appropriate aromatic effectors are present. Transcriptional activities from these promoters only occur upon transition to stationary phase, where nutrients become limiting (12, 68). Since this comparative study utilizes both the native P. putida and E. coli mutant strains, luxAB and lacZ reporter systems were tested in both hosts grown on LB. As a starting point, we chose reporter systems previously observed to be capable of reproducing the physiological control of DmpR/Po. In P. putida, the test system consists of a monocopy chromosomal insertion of the regulator and an RK2-based plasmid bearing the promoter fused to the luxAB or lacZ reporter gene. In E. coli, the regulator and the promoter-reporter fusions are carried together on RSF1010-based plasmids. The strains were grown in LB in the presence of an aromatic effector specific to each regulator, and reporter activities were assayed over growth. From the data shown in Fig. 2 it can be seen first that the genetic systems that exhibit physiologically responsive profiles for DmpR/Po also do so for XylR/Pu. Second, the transcriptional profiles obtained using luxAB (Fig. 2A to D) and lacZ (Fig. 2E to H) reporters are very similar. One minor difference is that a drop in transcriptional activity is more readily observed when using the luxAB reporter (e.g., compare Fig. 2C and G), probably due to the shorter half-lives of luxAB gene products. Nevertheless, the overall similarity indicates that the different reporters are unlikely to give dramatically different results. Therefore, in our comparative studies described below the luxAB reporters were routinely used, except in instances where a difference between the DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu physiological control had to be clearly established. In these cases, both reporters were used although only the luxAB data are presented.

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional profiles of DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu regulatory circuits in LB-grown P. putida (A, B, E, and F) and E. coli (C, D, G, and H), based on assays of luciferase (A to D) and β-galactosidase (β-gal; E to H) activities. Growth conditions are as stated in Materials and Methods. Solid symbols, log optical density at 600 nm (OD600); open symbols, relative luciferase units (RLU) and Miller β-galactosidase units.

Regulator expression levels in test strains.

The impact of physiologically significant control mechanisms on specific regulatory circuits can frequently be masked or diminished if the regulator levels are markedly elevated over those found in the parental systems. Therefore it is important that reporter systems maintain the expression levels close to that found in the native regulatory circuit. In a comparative analysis such as that performed here it would be ideal if a single reporter system could be used in all experiments. However, the nonavailability of key mutants in P. putida requires the use of E. coli strains. The native promoter of dmpR functions poorly in E. coli (68), which is also evident from the different comparative efficiencies of the DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu systems in P. putida versus E. coli in Fig. 2. This consideration, in combination with the antibiotic resistance markers of plasmids carrying other genes in trans, forced us to develop alternative genetic systems so that expression levels more closely reflecting those of the native system could be achieved. All the test systems used here were quantified for the levels of DmpR and XylR by Western analysis, and these levels were compared to the native expression levels from pVI150 and pWW0. As shown in Table 2, the relative expression of XylR is approximately 10-fold higher than that of DmpR when the two proteins are expressed from their native plasmids in the parental hosts. Importantly, with the P. putida monocopy systems, expression levels do not exceed 2.5 times the native level. The E. coli test systems have an overall two- to fourfold reduction in regulator expression compared to those of P. putida, despite being present on a 16-copy plasmid. Minor difference in regulator levels between E. coli mutants and their isogenic parents can be seen but are too small to account for the dramatic trends shown in the experiments described below.

FtsH is not universally required for ς54-dependent transcription.

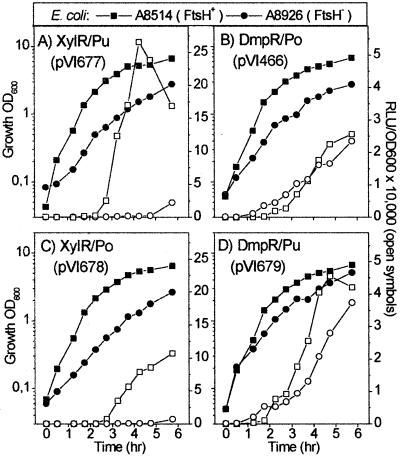

The levels of E. coli ATP-dependent FtsH protease are controlled in response to physiological cues. This protease is an essential factor for aerobic survival of E. coli, with ftsH mutations requiring an additional suppressor mutation in order for the bacteria to grow (55). In an FtsH− E. coli strain, XylR-mediated transcription from Pu is drastically reduced, as was transcription mediated by three other ς54-dependent regulators tested, NtrC, NifA, and PspF (8). This finding spurred the idea that FtsH is an essential element for Eς54 transcription, at least in E. coli (8). A search of the as yet unfinished P. putida KT2440 genomic database shows that there is an FtsH homologue (62% identity; data not shown) which may play a similar role in this host. Despite intensive efforts we were unable to generate a P. putida FtsH− mutant by a method that has proven productive for other host genes (see below), probably due to the essential nature of FtsH in P. putida. Therefore, we employed the same E. coli FtsH− mutant and parental strains as Carmona and coworkers (8) to test the effect of FtsH on the DmpR/Po circuit. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, while the XylR/Pu system is clearly defective in the absence of FtsH, the DmpR/Po system is fully functional. In addition, exponential-phase silencing of Po is somewhat diminished in the FtsH− mutant (Fig. 3B). Therefore, FtsH is not required for DmpR/Po transcription and is clearly not an essential factor for ς54-dependent transcription per se.

FIG. 3.

Luciferase transcriptional profiles of Po and Pu promoters activated by their native regulators (A and B) or nonnative regulators (C and D) in E. coli A8514 (FtsH+) and A8926 (FtsH−). Solid symbols, culture growth; open symbols, luciferase response. Note that, as has been found previously, the absolute values of reporters for different E. coli strains vary (68) and that transcriptional levels are higher in this lineage of E. coli than in the MG1655 lineage used in Fig. 2. RLU, relative luciferase units; OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

The observation that overexpression of FtsH abolishes exponential silencing of the XylR/Pu system in rich media, in conjunction with the findings that the defective transcription from Pu in the absence of FtsH can be partially rescued by ς54 overexpression, suggested a possible link to Ες54 availability and/or activity (8). While ς54 levels were not observed to differ from that of the parent in the FtsH− strain, one speculation, partly based on the fact that FtsH is involved in controlling turnover of the heat shock ς32 factor (4), was that FtsH may also directly or indirectly control ς54 turnover or activity (8). If this were the case, then the Pu transcription-defective phenotype of the FtsH− mutant strain would imply that the mutant contains less available Ες54 than its parent. Following this argument, the drastically different effects of FtsH on the XylR/Pu and DmpR/Po activity would have to be attributed to different promoter affinities for Ες54 and the phenomenon of FtsH dependence should accompany the promoter. Available in vitro data suggest that while the affinities of Po and Pu for Ες54 are similar in the presence of IHF, Po has a significantly higher apparent affinity than Pu in the absence of IHF (9, 67). Therefore, to test the contribution of promoter versus regulator to FtsH sensitivity, we performed regulator-swapping experiments in which the effects of FtsH on DmpR-mediated transcription of Pu and XylR-mediated transcription from Po were measured. As shown in Fig. 3C and D the data clearly demonstrate that the regulator, rather than the promoter, determines sensitivity to the absence of FtsH.

Western analysis of the levels of DmpR and XylR in the FtsH mutant strain indicate that DmpR levels are comparable to those found in the parent strain, while XylR levels are decreased approximately twofold (Table 2). However, the reduced levels of XylR are similar or higher than those found in other E. coli backgrounds (e.g., MG1655Δlac and CF1693Δlac) where XylR-mediated transcription is readily observed. While one cannot fully rule out the possibility that, for unknown reasons, higher threshold levels of XylR may be required to promote transcription in the A8514 E. coli lineage, the data described above suggest that the effect of FtsH is channeled through some differentiating property of XylR and DmpR other than expression levels. Circumstantial evidence suggested that, besides being a protease, FtsH can act as a chaperone (reviewed in reference 59). Indeed, multiple sequence alignment combined with advanced computer methods for iterative databases placed FtsH in the AAA+ superfamily of chaperone-like ATPases. This family of proteins often act like “molecular machines,” performing functions that assist in assembly, operation, or disassembly of protein complexes, and ς54-dependent activators themselves fall into a subgroup within this superfamily (46). Where tested, ς54-dependent regulators have been found to oligomerize from lower- to higher-order multimeric states in response to signal reception and nucleotide binding by the central C domain (e.g., NtrC [27, 43] and XylR [51]). This is also the case for DmpR; however, unlike XylR and other ς54 regulators, DmpR readily undergoes oligomerization in the absence of DNA binding (71). This raises the intriguing possibility that for the FtsH-dependent ς54 regulators, FtsH may be required for correct folding or for proper assembly and/or disassembly of regulator multimers or regulator-Ες54 complexes.

PtsN mediates glucose repression of the XylR/Pu system but not the DmpR/Po system.

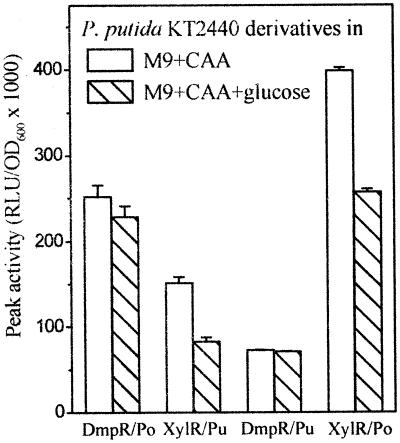

XylR/Pu is subject to an additional level of physiological regulation, in which the presence of glucose reduces the level of transcription from Pu by two- to threefold. Work with the native P. putida host has previously shown that this level of regulation involves the ptsN gene, which encodes the IIANtr component for an alternative PTS, located in a gene cluster downstream of rpoN (11, 14). To test if this level of control is manifested in the DmpR/Po regulatory circuit, we employed the same P. putida KT2440 background. To maintain the same growth rate independent of the presence or absence of glucose, we also used the same medium conditions as Cases and colleagues (14), namely, M9 minimal media supplemented with casein amino acids in the presence and absence of glucose. P. putida reporter strains consisting of a monocopy of the regulator gene on the chromosome and RK2-based promoter-luxAB reporters were used to monitor DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu transcription. Promoter activities were monitored over growth, and the values shown in Fig. 4 are those taken at postexponential phase, where the activities were observed to be in their peaks. Note that growth in these media results in three- to fivefold-higher promoter activities than growth in LB (Fig. 2A and B). The data in Fig. 4 show that no effect of glucose is imposed on the DmpR/Po system while a twofold effect, as observed previously, was found with the analogous XylR/Pu reporter. To ascertain that this was not a result of the rather low XylR/DmpR expression ratio of the test system (Table 2), the experiment was repeated with the other P. putida luxAB reporter systems available, i.e., the KT2440::dmpR-Po-luxAB and KT2440::xylR-Pu-luxAB strains, with similar results (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Luciferase activity of P. putida KT2440::dmpR-Km and KT2440::xylR-Km carrying RK2-based plasmid pVI673 (Po-luxAB) or pVI674 (Pu-luxAB). Cells were grown in M9 media with 0.2% casein amino acids (CAA) and the appropriate aromatic effector and further supplemented with 10 mM glucose where indicated. Peak activities shown are averages of triplicate determinations from two independent experiments. RLU, relative luciferase activity.

Regulator-swapping experiments demonstrate that the susceptibility to glucose repression depends on the identity of the regulators (Fig. 4). We infer from this that, like the action of FtsH, the mechanism by which PtsN functions is channeled through the activity of the regulator rather than the inherent properties of the promoter. The function of the P. putida ptsN-encoded IIANtr enzyme has not yet been elucidated (14). However, PTSs have regulatory roles besides phosphotransfer of sugars across the membrane, e.g., generation of signals for catabolite repression, nitrogen metabolism, and chemotaxis (56, 66). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of a P. putida ptsN mutant shows that PtsN has global effects on protein expression and that these effects do not affect all ς54-dependent promoters and the effects are not limited to ς54-dependent genes (13). Whatever the precise mechanism by which the P. putida glucose-PtsN link impacts on XylR, it clearly does not intercept DmpR. Hence, like FtsH, PtsN represents a regulatory factor that impacts the XylR/Pu system but not the DmpR/Po system and mediates its effect via the regulator rather than the promoter.

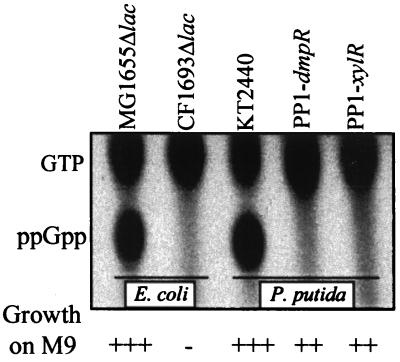

(p)ppGpp0 E. coli and P. putida differ in prototrophy.

Production of the signaling molecule (p)ppGpp is a herald of metabolic stress. In E. coli the ribosome-bound RelA (p)ppGpp synthetase catalyzes the production of (p)ppGpp from GTP when activated by the arrival of an uncharged tRNA on the ribosome, while SpoT (which is primarily responsible for [p]ppGpp degradation), catalyzes (p)ppGpp synthesis in response to glucose starvation (reviewed in reference 15). The binding of (p)ppGpp to RNA polymerase results in a reorganization of the global transcriptional patterns in response to the changing growth conditions primarily by down-regulating transcription from stringent promoters (reviewed in references 15 and 16). A role for (p)ppGpp in up-regulation of transcription from Po and as the metabolic link between host physiology and the DmpR/Po regulatory system was first indicated by the finding that transcription of the DmpR/Po system was dependent on growth conditions that elicit high (p)ppGpp levels. Further evidence came from the findings that gratuitous synthesis of (p)ppGpp under normally nonpermissive conditions abolished exponential silencing in P. putida and that the drastically reduced transcription from Po in a (p)ppGpp0 E. coli strain could be rescued by mutations within the transcriptional apparatus (69). Similar gratuitous production of (p)ppGpp, monitored using a lacZ reporter, likewise abolished exponential silencing of the XylR/Pu system in LB. However, in a (p)ppGpp0 E. coli background, the reduction in transcriptional activity was minimal (10).

To assess the dependence of the two systems on (p)ppGpp in their native P. putida host, we generated a (p)ppGpp0 strain of KT2440. With E. coli RelA and SpoT, a search of the as yet unfinished P. putida KT2440 genomic database identified a single RelA homologue (47% identity, 68% similarity) and a single SpoT homologue (54% identity, 72% similarity) in this strain. As shown in Fig. 5, like its E. coli counterpart, the P. putida double mutant is a full (p)ppGpp0 strain, suggesting that no other (p)ppGpp synthetase exists in KT2440. However, unlike their E. coli (p)ppGpp0 counterpart, the (p)ppGpp0 P. putida strains are prototrophic, being able to grow on minimal media lacking amino acids (Fig. 5). Both the E. coli and P. putida double mutants were generated by similar gene replacement strategies in which the internal portions of the relA and spoT genes are replaced by antibiotic resistance genes (see Materials and Methods). Prototrophy of E. coli appears to be in fine balance since single amino acid substitutions of RNA polymerase that restore prototrophy to (p)ppGpp0 strains can readily be selected on minimal media (15, 33). Our P. putida strain construction strategy avoided growth on anything but rich media. Moreover, >10 independent (p)ppGpp0 P. putida isolates have been tested both with respect to prototrophy and their expression profiles by using a Po-luxAB reporter. All derivatives exhibit the same behavior; thus we conclude that the difference in the ability to grow on minimal media in the absence of amino acids is a genuine difference between (p)ppGpp0 derivatives of E. coli and P. putida. Given the above and the fact that the amino acid sequences of the components of the transcriptional apparatus of E. coli and P. putida are divergent (examples of identities: RpoB, 74%; RpoC, 75%; RpoD, 66%; RpoN, 56%; data not shown), a difference in prototrophy is not surprising and probably reflects differences in the abundance and/or properties of the RNA polymerases.

FIG. 5.

Chromatographic analysis of 32P-labeled nucleotides of the indicated E. coli and P. putida strains as described in Materials and Methods. The abilities of the strains to grow on M9 minimal medium plates supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 100 μg of thiamine/ml are indicated (bottom).

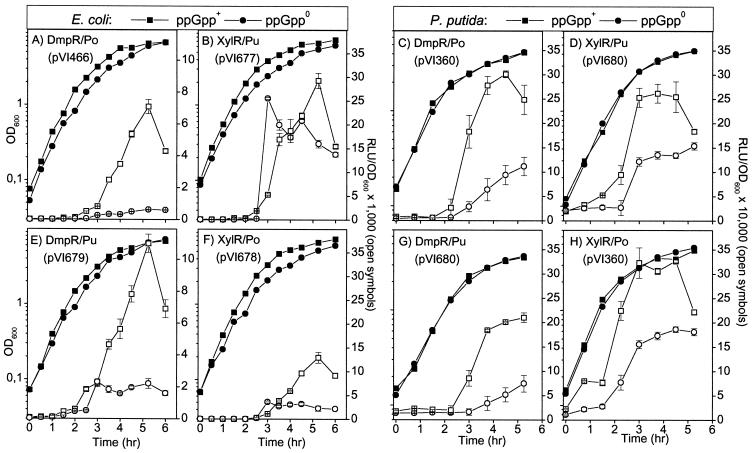

Influence of (p)ppGpp on the DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu circuits in E. coli and P. putida.

Luciferase reporter plasmids were introduced into (p)ppGpp+ E. coli and P. putida strains and their otherwise isogenic (p)ppGpp0 counterparts. For E. coli, the reporter systems consisted of RSF1010-based plasmids carrying both the regulator and promoter-luxAB fusion, while for P. putida, the regulators were at monocopy on the chromosome, with the promoter-luxAB fusions carried on RSF1010-based plasmids. In E. coli, DmpR-mediated regulation of Po transcription decreases by approximately 10-fold (Fig. 6A) while XylR-mediated Pu transcription is only marginally affected, with maximum reduction of a mere 30 to 50% (Fig. 6B). These results reaffirm the marginal dependence of the XylR/Pu circuit on (p)ppGpp, in marked contrast to the strong dependence of the DmpR/Po circuit in E. coli. However, a somewhat different result was found with P. putida. In the native host, the DmpR/Po system is still strongly dependent on (p)ppGpp (Fig. 6C), although to a lesser extent than in E. coli. For XylR/Pu, the expression profiles in the ppGpp+ and ppGpp0 strains both still exhibit an abrupt shift in expression at the transition from exponential to stationary phase, but with the maximum level achieved in the ppGpp0 strain reduced to approximately that observed with the ppGpp+ strain after prolonged incubation (Fig. 6D). Thus while the basic trends and main conclusions drawn from the work in E. coli are verified in P. putida, the magnitude of dependence of the two systems in the different hosts varies.

FIG. 6.

Luciferase transcriptional profiles of Po and Pu promoters activated by their native regulators (A to D) or nonnative regulators (E to H), in isogenic E. coli (A, B, E, and F) and P. putida (C, D, G, and H) (p)ppGpp+ and (p)ppGpp0 strains. E. coli (p)ppGpp+ MG1655Δlac and (p)ppGpp0 CF1693Δlac strains and P. putida (p)ppGpp+ KT2440-dmpR-Tel and -xylR-Tel and (p)ppGpp0 PP1-dmpR and -PP1-xylR strains were used. Solid symbols, culture growth; open symbols, luciferase response. RLU, relative luciferase units; OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

The above finding raises the question of what factors determine the somewhat different responses in the two hosts. Work with E. coli demonstrated that lack of (p)ppGpp does not greatly affect the levels of DmpR or ς54 (69). Western analysis comparing DmpR and XylR levels in the E. coli and P. putida (p)ppGpp+ and (p)ppGpp0 strains did not reveal any detectable differences between the parents and mutant derivatives (Table 2). Therefore, expression levels of these key players are unlikely to explain the differences observed with reporters in E. coli and P. putida.

Binding of (p)ppGpp to the transcriptional apparatus is believed to occur through a site at an interface of the β- and β′-subunit (RpoB, RpoC), with binding affecting multiple steps in transcription from specific promoters (reviewed in references 15 and 16). One major consequence of the resulting negative regulation of stringent promoters is an increase in the amount of limiting core RNA polymerase. A growing body of genetic evidence has suggested that (p)ppGpp binding may also influence the outcome of sigma factor competition for the available core enzyme (26, 33, 38, 69) and may thereby alter the amount of holoenzyme associated with alternative sigma factors. Hence differences in the amount of available Eς54 may in part be responsible for the higher Po output observed in (p)ppGpp0 P. putida.

In addition to direct effects on promoter kinetics, accumulation of ppGpp in vivo can also have major indirect effects on promoter activity due to its influence on transcription of global regulatory factors such as ςs and IHF (3, 32). IHF is needed for optimal promoter output from both the DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu systems (9, 67). For DmpR/Po, the system is equally dependent on IHF in both E. coli and P. putida, and coexpression experiments have demonstrated that additional IHF does not relieve the dramatic reduction in transcription from Po in (p)ppGpp0 E. coli (67, 69). However, the XylR/Pu system is much more dependent on IHF in P. putida than in E coli (6). Hence, it is possible that indirect effects on IHF levels may play a role in the reduction of Pu output in (p)ppGpp0 P. putida.

Role of the promoter versus regulator in sensitivity to the absence of (p)ppGpp.

To see if the difference in the influence of (p)ppGpp on the DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu systems could be ascribed to regulator or promoter properties, regulator-swapping experiments were performed with both hosts. The data show that, in the E. coli (p)ppGpp0 background, DmpR-driven Pu transcription is reduced by about fivefold (Fig. 6E) while XylR-driven transcription from Po was reduced three- to fourfold (Fig. 6F). Thus, having either component of the DmpR/Po pair renders the system more dependent on (p)ppGpp, although not to the same extent (10-fold) as for the original pair. In P. putida, on the other hand, the nature of the regulator is the predominant component that determines the transcriptional outcome, since profiles with the cognate and noncognate promoters are very similar (Fig. 6C, D, G, and H). Hence, in both E. coli and P. putida, the nature of the regulator plays a dominant role in the sensitivity to the absence of (p)ppGpp. The simplest interpretation of this finding is that ppGpp binding to Ες54, in addition to its other effects, also modulates the efficiency with which DmpR interacts with Ες54 to relieve the repressive effect of ς54 on core polymerase activity.

The multitude of effects of the (p)ppGpp signaling molecule in vivo makes it difficult to put quantitative levels on the contribution of the different regulatory mechanisms of (p)ppGpp to physiological coupling. Nevertheless, the finding that mutations in the transcriptional apparatus can restore transcription to the DmpR/Po circuit provides strong support for direct effects of (p)ppGpp on Po promoter kinetics (69). Further support for this conclusion has been provided by the recent demonstration of a four- to sixfold ppGpp-mediated stimulation of in vitro transcription from Po by an N-terminally truncated derivative of XylR (10). In addition to showing direct effects on promoter kinetics, previous work has provided genetic evidence for a role for (p)ppGpp in altering sigma factor competition in favor of ς54, which may also contribute to the rapid transition and higher net transcriptional output of Po in (p)ppGpp+ strains (Fig. 6) (69). The data in Fig. 6 add a third potential influence of (p)ppGpp on metabolic coupling by providing suggestive evidence for a role for (p)ppGpp in modulating the conformation of the transcriptional apparatus to allow efficient interaction with DmpR. The contribution of (p)ppGpp to each of these processes in vitro certainly warrants more attention and is the focus of our future research.

Concluding remarks.

The work presented here demonstrates that DmpR/Po and XylR/Pu regulatory circuits, two mechanistically and functionally similar ς54 regulator/promoter pairs, are integrated into the global regulatory network through different host factors. Neither of the two factors identified to impact the XylR/Pu system (FtsH and PtsN) influences the DmpR/Po system, while (p)ppGpp impacts the DmpR/Po system to a much greater extent than the XylR/Pu system. The comparative analysis presented here illustrates that host-imposed regulation of these systems predominantly exploits properties of the specific regulator to exert dominant regulatory control over the specific regulatory circuits. However, despite the integration of different global factors, the biological outcome is functionally analogous: a transcriptional response adapted to initiate aromatic degradation only in the absence of other preferred nutrients. This is interesting not only from the mechanistic but also the evolutionary point of view. Sequence comparison of aromatic catabolic operons reveals a “patchwork” assembly pattern suggesting evolutionary recruitment of simple metabolic modules to generate catabolic pathways (reviewed in reference 72). The acquisition of specific regulatory genes has likewise been proposed to occur in a patchwork manner involving recruitment of regulators that happen to have some appropriate signal response property that can be further refined through selection (21). This work suggests that integration of dominant global regulatory circuits can similarly occur in a patchwork manner in which global regulatory factors latch onto different properties of the specific regulatory circuit. It is possible that the interconnecting and overlapping nature of global regulatory networks bypasses the need for specific regulatory units to be woven into the tapestry of cellular physiology at one specific point in order to achieve analogous biological output.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to M. Carmona, I. Cases, and V. de Lorenzo for providing reagents, for communicating results prior to publication, and for fruitful discussion.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Councils for Natural and Engineering Sciences, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, and the J. C. Kempe Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abril, M. A., M. Buck, and J. L. Ramos. 1991. Activation of the Pseudomonas TOL plasmid upper pathway operon. Identification of binding sites for the positive regulator XylR and for integration host factor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15832–15838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ampe, F., D. Leonard, and N. D. Lindley. 1998. Repression of phenol catabolism by organic acids in Ralstonia eutropha. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aviv, M., H. Giladi, G. Schreiber, A. B. Oppenheim, and G. Glaser. 1994. Expression of the genes coding for the Escherichia coli integration host factor are controlled by growth phase. rpoS, ppGpp and by autoregulation. Mol. Microbiol. 14:1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaszczak, A., C. Georgopoulos, and K. Liberek. 1999. On the mechanism of FtsH-dependent degradation of the ς32 transcriptional regulator of Escherichia coli and the role of the DnaK chaperone machine. Mol. Microbiol. 31:157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bochner, B. R., and B. N. Ames. 1982. Complete analysis of cellular nucleotides by two-dimensional thin layer chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 257:9759–9769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calb, R., A. Davidovitch, S. Koby, H. Giladi, D. Goldenberg, H. Margalit, A. Holtel, K. Timmis, J. M. Sanchez-Romero, V. de Lorenzo, and A. B. Oppenheim. 1996. Structure and function of the Pseudomonas putida integration host factor. J. Bacteriol. 178:6319–6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon, W. V., M. T. Gallegos, and M. Buck. 2000. Isomerization of a binary sigma-promoter DNA complex by transcription activators Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmona, M., and V. de Lorenzo. 1999. Involvement of the FtsH (HflB) protease in the activity of ς54 promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 31:261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmona, M., V. de Lorenzo, and G. Bertoni. 1999. Recruitment of RNA polymerase is a rate-limiting step for the activation of the ς54 promoter Pu of Pseudomonas putida J. Biol. Chem. 274:33790–33794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmona, M., M. J. Rodriguez, O. Martinez-Costa, and V. de Lorenzo. 2000. In vivo and in vitro effects of (p)ppGpp on the ς54 promoter Pu of the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 182:4711–4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cases, I., and V. de Lorenzo. 2000. Genetic evidence of distinct physiological regulation mechanisms in the ς54 Pu promoter of Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 182:956–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cases, I., V. de Lorenzo, and J. Perez-Martin. 1996. Involvement of ς54 in exponential silencing of the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid Pu promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 19:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cases, I., J. A. Lopez, J. P. Albar, and V. de Lorenzo. 2001. Evidence of multiple regulatory functions for the PtsN (IIANtr) protein of Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 183:1032–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cases, I., J. Pérez-Martín, and V. de Lorenzo. 1999. The IIANtr (PtsN) protein of Pseudomonas putida mediates the C source inhibition of the ς54-dependent Pu promoter of the TOL plasmid. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15562–15568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cashel, M., D. Gentry, V. J. Hernandez, and D. Vinella. 1996. The stringent response, p.1458–1496. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. I. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Chatterji, D., and A. K. Ojha. 2001. Revisiting the stringent response, ppGpp and starvation signaling. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corkery, D. M., K. E. O’Connor, C. M. Buckley, and A. D. Dobson. 1994. Ethylbenzene degradation by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain CA-4. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Lorenzo, V., S. Fernández, M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Engineering of alkyl- and haloaromatic-responsive gene expression with mini-transposons containing regulated promoters of biodegradative pathways of Pseudomonas. Gene 130:41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6568–6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, M. Metzke, and K. N. Timmis. 1991. An upstream XylR- and IHF-induced nucleoprotein complex regulates the ς 54-dependent Pu promoter of TOL plasmid. EMBO J. 10:1159–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Lorenzo, V., and J. Pérez-Martín. 1996. Regulatory noise in prokaryotic promoters: how bacteria learn to respond to novel environmental signals. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1177–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Lorenzo, V., and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol. 235:386–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennis, J. J., and G. J. Zylstra. 1998. Improved antibiotic-resistance cassettes through restriction site elimination using Pfu DNA polymerase PCR. BioTechniques 25:772–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dennis, J. J., and G. J. Zylstra. 1998. Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2710–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duetz, W. A., S. Marqués, C. de Jong, J. L. Ramos, and J. G. van Andel. 1994. Inducibility of the TOL catabolic pathway in Pseudomonas putida (pWW0) growing on succinate in continuous culture: evidence of carbon catabolite repression control. J. Bacteriol. 176:2354–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farewell, A., K. Kvint, and T. Nyström. 1998. Negative regulation by RpoS: a case of sigma factor competition. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1039–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farez-Vidal, M. E., T. J. Wilson, B. E. Davidson, G. J. Howlett, S. Austin, and R. A. Dixon. 1996. Effector-induced self-association and conformational changes in the enhancer-binding protein NTRC. Mol. Microbiol. 22:779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernández, S., V. de Lorenzo, and J. Pérez-Martín. 1995. Activation of the transcriptional regulator XylR of Pseudomonas putida by release of repression between functional domains. Mol. Microbiol. 16:205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernández, S., V. Shingler, and V. de Lorenzo. 1994. Cross-regulation by XylR and DmpR activators of Pseudomonas putida suggests that transcriptional control of biodegradative operons evolves independently of catabolic genes. J. Bacteriol. 176:5052–5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fürste, J. P., W. Pansegrau, R. Frank, H. Blöcker, P. Scholz, M. Bagdasarian, and E. Lanka. 1986. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene 48:119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heitzer, A., K. Malachowsky, J. E. Thonnard, P. R. Bienkowski, D. C. White, and G. S. Sayler. 1994. Optical biosensor for environmental on-line monitoring of naphthalene and salicylate bioavailability with an immobilized bioluminescent catabolic reporter bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1487–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hengge-Aronis, R. 1996. Regulation of gene expression during entry into stationary phase, p.1497–1512. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtis III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. I. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Hernandez, V. J., and M. Cashel. 1995. Changes in conserved region 3 of Escherichia coli ς70 mediate ppGpp-dependent functions in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 252:536–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N., T. Köhler, M. Rekik, and S. Harayama. 1990. Growth-phase-dependent expression of the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid pWW0 catabolic genes. J. Bacteriol. 172:6651–6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inouye, S., A. Nakazawa, and T. Nakazawa. 1987. Expression of the regulatory gene xylS on the TOL plasmid is positively controlled by the xylR gene product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:5182–5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanaly, R. A., and S. Harayama. 2000. Biodegradation of high-molecular-weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 182:2059–2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly, M. T., and T. R. Hoover. 2000. The amino terminus of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ς54 is required for interactions with an enhancer-binding protein and binding to fork junction DNA. J. Bacteriol. 182:513–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kvint, K., A. Farewell, and T. Nyström. 2000. RpoS-dependent promoters require guanosine tetraphosphate for induction even in the presence of high levels of ςS. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14795–14798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lodge, J., R. Williams, A. Bell, B. Chan, and S. Busby. 1990. Comparison of promoter activities in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: use of a new broad-host-range promoter-probe plasmid. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 55:221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marqués, S., A. Holtel, K. N. Timmis, and J. L. Ramos. 1994. Transcriptional induction kinetics from the promoters of the catabolic pathways of TOL plasmid pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida for metabolism of aromatics. J. Bacteriol. 176:2517–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marqués, S., and J. L. Ramos. 1993. Transcriptional control of the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid catabolic pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 9:923–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFall, S. M., B. Abraham, C. G. Narsolis, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1997. A tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediate regulating transcription of a chloroaromatic biodegradative pathway: fumarate-mediated repression of the clcABD operon. J. Bacteriol. 179:6729–6735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mettke, I., U. Fiedler, and V. Weiss. 1995. Mechanism of activation of a response regulator: interaction of NtrC-P dimers induces ATPase activity. J. Bacteriol. 177:5056–5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 45.Neidhardt, F. C., P. L. Bloch, and D. F. Smith. 1974. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 119:736–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neuwald, A. F., L. Aravind, J. L. Spouge, and E. V. Koonin. 1999. AAA+: a class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 9:27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ng, L. C., E. O’Neill, and V. Shingler. 1996. Genetic evidence for interdomain regulation of the phenol-responsive final ς54-dependent activator DmpR. J. Biol. Chem. 271:17281–17286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Neill, E., L. C. Ng, C. C. Sze, and V. Shingler. 1998. Aromatic ligand binding and intramolecular signalling of the phenol-responsive ς54-dependent regulator DmpR. Mol. Microbiol. 28:131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Neill, E., P. Wikstrom, and V. Shingler. 2001. An active role for a structured B-linker in effector control of the ς54-dependent regulator DmpR. EMBO J. 20:819–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pavel, H., M. Forsman, and V. Shingler. 1994. An aromatic effector specificity mutant of the transcriptional regulator DmpR overcomes the growth constraints of Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600 on para-substituted methylphenols. J. Bacteriol. 176:7550–7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pérez-Martín, J., and V. de Lorenzo. 1996. ATP binding to the ς54-dependent activator XylR triggers a protein multimerization cycle catalyzed by UAS DNA. Cell 86:331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pérez-Martín, J., and V. de Lorenzo. 1996. Identification of the repressor subdomain within the signal reception module of the prokaryotic enhancer-binding protein XylR of Pseudomonas putida. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7899–7902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pérez-Martín, J., and V. de Lorenzo. 1996. Physical and functional analysis of the prokaryotic enhancer of the ς54-promoters of the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida. J. Mol. Biol. 258:562–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powlowski, J., and V. Shingler. 1994. Genetics and biochemistry of phenol degradation by Pseudomonas sp. CF600. Biodegradation 5:219–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qu, J. N., S. I. Makino, H. Adachi, Y. Koyama, Y. Akiyama, K. Ito, T. Tomoyasu, T. Ogura, and H. Matsuzawa. 1996. The tolZ gene of Escherichia coli is identified as the ftsH gene. J. Bacteriol. 178:3457–3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saier, M. H., Jr., and J. Reizer. 1994. The bacterial phosphotransferase system: new frontiers 30 years later. Mol. Microbiol. 13:755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 58.Sanchez-Romero, J. M., R. Diaz-Orejas, and V. de Lorenzo. 1998. Resistance to tellurite as a selection marker for genetic manipulations of Pseudomonas strains. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 64:4040–4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schumann, W. 1999. FtsH—a single-chain charonin? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shingler, V., M. Bartilson, and T. Moore. 1993. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the positive regulator (DmpR) of the phenol catabolic pathway encoded by pVI150 and identification of DmpR as a member of the NtrC family of transcriptional activators. J. Bacteriol. 175:1596–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shingler, V., F. C. Franklin, M. Tsuda, D. Holroyd, and M. Bagdasarian. 1989. Molecular analysis of a plasmid-encoded phenol hydroxylase from Pseudomonas CF600. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:1083–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shingler, V., and T. Moore. 1994. Sensing of aromatic compounds by the DmpR transcriptional activator of phenol-catabolizing Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600. J. Bacteriol. 176:1555–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shingler, V., and H. Pavel. 1995. Direct regulation of the ATPase activity of the transcriptional activator DmpR by aromatic compounds. Mol. Microbiol. 17:505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shingler, V., J. Powlowski, and U. Marklund. 1992. Nucleotide sequence and functional analysis of the complete phenol/3,4-dimethylphenol catabolic pathway of Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600. J. Bacteriol. 174:711–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skärfstad, E., E. O’Neill, J. Garmendia, and V. Shingler. 2000. Identification of an effector specificity subregion within the aromatic-responsive regulators DmpR and XylR by DNA shuffling. J. Bacteriol. 182:3008–3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stülke, J., and W. Hillen. 1999. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sze, C. C., A. D. Laurie, and V. Shingler. 2001. In vivo and in vitro effects of integration host factor at the DmpR-regulated ς54-dependent Po promoter. J. Bacteriol. 183:2842–2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sze, C. C., T. Moore, and V. Shingler. 1996. Growth phase-dependent transcription of the ς54-dependent Po promoter controlling the Pseudomonas-derived (methyl)phenol dmp operon of pVI150. J. Bacteriol. 178:3727–3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sze, C. C., and V. Shingler. 1999. The alarmone (p)ppGpp mediates physiological-responsive control at the ς54-dependent Po promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1217–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang, J. T., A. Syed, M. Hsieh, and J. D. Gralla. 1995. Converting Escherichia coli RNA polymerase into an enhancer-responsive enzyme: role of an NH2-terminal leucine patch in ς54. Science 270:992–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wikström, P., E. O’Neill, L. C. Ng, and V. Shingler. 2001. The regulatory N-terminal region of the aromatic-responsive transcriptional activator DmpR constrains nucleotide-triggered multimerisation. J. Mol. Biol. 314:971–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams, P. A., and J. R. Sayers. 1994. The evolution of pathways for aromatic hydrocarbon oxidation in Pseudomonas. Biodegradation 5:195–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]