Abstract

Plant heterotrimeric G-proteins have been implicated in a number of signaling processes. However, most of these studies are based on biochemical or pharmacological approaches. To examine the role of heterotrimeric G-proteins in plant development, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis expressing the Gα subunit of the heterotrimeric G-protein under the control of a glucocorticoid-inducible promoter. With the conditional overexpression of either the wild type or a constitutively active version of Arabidopsis Gα, transgenic seedlings exhibited a hypersensitive response to light. This enhanced light sensitivity was more exaggerated in a relatively lower intensity of light and was observed in white light as well as far-red, red, and blue light conditions. The enhanced responses in far-red and red light required functional phytochrome A and phytochrome B, respectively. Furthermore, the response to far-red light depended on functional FHY1 but not on FIN219 and FHY3. This dependence on FHY1 indicates that the Arabidopsis Gα protein may act only on a discrete branch of the phytochrome A signaling pathway. Thus, our results support the involvement of a heterotrimeric G-protein in the light regulation of Arabidopsis seedling development.

INTRODUCTION

Heterotrimeric G-proteins are conserved cell signaling molecules in various eukaryotic organisms such as yeast, Dictyostelium, animals, and plants. They regulate diverse developmental processes in these organisms. For example, in yeast, a heterotrimeric G-protein mediates changes in cell shape by stabilizing the axis of polarity (Nern and Arkowitz, 2000), and a maternal G-protein was found to be important for the orientation of cell division axes in early Caenorhabditis elegans embryos (Zwaal et al., 1996). In most cases, heterotrimeric G-proteins are involved in the propagation of perceived signals.

Perception and interpretation of environmental cues are the most important processes for immotile organisms such as plants. Heterotrimeric G-proteins have been implicated in several processes during growth and development, and they transduce extracellular environmental signals to the cell. In general, heterotrimeric G-proteins consist of three subunits: α, β, and γ. Analysis of the complete genome sequence (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000) indicates that the Arabidopsis genome contains only a single Gα gene, previously designated AtGPA1 (Ma et al., 1990), and a single Gβ gene, designated AGB1 (Weiss et al., 1994). Genes homologous with Arabidopsis Gα and Gβ also have been found in other plant species. The Arabidopsis genome sequencing program did not identify obvious Gγ sequences in Arabidopsis, although there is some biochemical evidence to suggest that plants may have a membrane-associated Gγ-like protein (Obrdlik et al., 2000). Recently, the Arabidopsis Gγ subunit was identified by a yeast two-hybrid screen using Gβ as bait (Mason and Botella, 2001). It was shown that Gγ also is encoded by a single copy gene in Arabidopsis.

In plants, the Gα subunit is the most intensively studied of the three subunits of the complex. AtGPA1 of Arabidopsis encodes a protein of 383 amino acids and 45 kD. This protein shows 36% identity and 73% similarity to Gαi of mammals and Gαt of vertebrates (Ma, 1994). It also has the conserved arginine residue that is predicted to be the target site for cholera toxin in vertebrate Gα (Ma et al., 1990). The transcript is most abundant in vegetative tissue (Huang et al., 1994). The Gα protein is detected during all stages of Arabidopsis development except in mature seed and is found in virtually all parts, from roots and leaves to the reproductive organs (Weiss et al., 1993). It is closely associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and the plasma membrane (Weiss et al., 1997). In rice, Gα antisense expressor lines show a dwarf phenotype in overall morphology at all stages of development (Fujisawa et al., 1999). In addition, five alleles of dwarf1 (d1), which was classified originally as a gibberellin-insensitive mutant, have been found to have mutations in a heterotrimeric Gα gene (Ashikari et al., 1999; Fujisawa et al., 1999; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2000), suggesting an involvement in gibberellin signal transduction. Various drug application studies have suggested that Gα is involved in gibberellin induction of the α-amylase gene in oat aleurone cells (Jones et al., 1998). In addition, the regulation of stomata opening (Assmann, 1996), pollen tube elongation in lily (Ma et al., 1999), and light signaling pathways in tomato cells (Neuhaus et al., 1993) have been reported to be regulated by heterotrimeric G-proteins. On the basis of cell biological and pharmacological studies, it has been proposed that a heterotrimeric G-protein acts downstream of phytochrome A and phytochrome B photoreceptors (Neuhaus et al., 1993; Kunkel et al., 1996).

Among all of the known photoreceptors in plants, the red (R) and far-red (FR) light–absorbing phytochromes are the most well-characterized molecules. They are encoded by a family of five genes (PHYA to PHYE) in Arabidopsis (Sharrock and Quail, 1989). The proteins encoded by these genes covalently attach a tetrapyrrole chromophore to form functional phytochromes. Phytochrome is synthesized in darkness as an R light–absorbing form and is converted to the FR light–absorbing form (Pfr) upon R light absorption. Although phytochromes have partially overlapping functions, it was established that phytochrome A (phyA) is the primary photoreceptor for FR light–mediated inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (Nagatani et al., 1993; Parks and Quail, 1993; Whitelam et al., 1993), whereas phytochrome B (phyB) was found to be the primary photoreceptor for R light–mediated inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (Reed et al., 1993). phyA also mediates, in addition to hypocotyl elongation, other FR light–regulated processes, such as the induction of germination, the induction of light-regulated genes, and an FR light block of the greening response.

The FR light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation has been used as a marker for mutations defective in phyA-specific signaling components. The first two mutants identified as such are fhy1-1 and fhy3-1 (Whitelam et al., 1993). Although both mutants are defective in phytochrome-mediated FR light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation, they still possess some phyA-mediated responses in FR light. Studies of these mutants have suggested that the phyA signal transduction is branched. Recently, a number of additional mutants that are defective in FR light regulation of hypocotyl elongation have been isolated. These are fin2, spa1, far1, pat1, fin219, and hfr1/rsf1/rep1 (Soh et al., 1998, 2000; Hoecker et al., 1999; Hudson et al., 1999; Bolle et al., 2000; Fairchild et al., 2000; Fankhauser and Chory, 2000; Hsieh et al., 2000). The responsible genes have been identified except for fin2. These genes encode both nuclear (SPA1, FAR1, and HFR1) and cytoplasmic (PAT1 and FIN219) proteins. In addition, yeast two-hybrid screens also have identified proteins that interact directly with phyA and/or phyB. These are PIF3, PKS1, and NDPK2 (Ni et al., 1998; Choi et al., 1999; Fankhauser et al., 1999). Interestingly, PIF3 has a bHLH domain that binds to DNA and was shown to act as a transcription factor (Martinez-Garcia et al., 2000). The HFR1 protein also possesses a bHLH domain and was shown to interact with the PIF3 protein and possibly form a heterodimer (Fairchild et al., 2000). It was demonstrated that both phyA and phyB molecules are imported from the cytoplasm into the nucleus upon R and/or FR irradiation (Kircher et al., 1999; Yamaguchi et al., 1999). Thus, it is plausible that phytochromes could serve as a direct regulator of these transcription factors. However, phytochrome signaling also must involve cytoplasmic events, because PKS1, PAT1, and FIN219 proteins were found primarily in the cytoplasm. In addition, it has been suggested that the secondary messengers, such as cytosolic free calcium and cyclic GMP, could be involved in the phytochrome signaling pathway and act downstream of the heterotrimeric G-protein (Neuhaus et al., 1993; Bowler et al., 1994).

In this study, we designed a transgenic approach to examine whether a heterotrimeric G-protein is involved in the phytochrome signal transduction pathway. We have generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants that are inducible overexpressors of the heterotrimeric Gα protein, AtGPA1. The transgenes were placed under a glucocorticoid-inducible promoter (Aoyama and Chua, 1997). Our analyses of these transgenic plants suggest that Gα overexpression can result in enhanced responses to light and that these phenotypes are dependent on functional phyA and phyB. Thus, this study provides physiological evidence of the involvement of heterotrimeric G-protein in light-regulated seedling development.

RESULTS

Construction of Gα-Inducible Arabidopsis Transgenic Lines

Two versions of AtGPA1, the wild-type full-length protein (wGα; Ma et al., 1990) and a constitutively active form of AtGPA1 (cGα; see Methods), were placed under the control of a glucocorticoid-inducible promoter (Aoyama and Chua, 1997) that could be activated by exogenously applied dexamethasone (DEX). A potential constitutively active form of AtGPA1 was generated by a point mutation of Glu-222 to Leu. This mutation was shown to disable the GTPase activity of Gα so that, once activated, it is locked as an active molecule (Aharon et al., 1998). Both transgenes were introduced into wild-type Arabidopsis.

The transgenic T2 lines that had segregated to give 75% hygromycin-resistant plants and thus were likely to contain a single insertion of the transgene were selected (15 for wGα and 17 for cGα). These lines were subjected to a screen on a plate containing DEX. These plates were placed under dim white light (10 μmol·m−2·sec−1) for 5 days, and the seedlings were compared with wild-type or empty vector transgenic plants grown on the same plates. Under these conditions, 5 of 15 lines of wGα and 8 of 17 lines of cGα segregated to give a population with 75% of the seedlings having a short hypocotyl phenotype relative to the wild type and the empty vector controls. The hygromycin resistance cosegregated tightly with the shorter hypocotyl phenotype. We chose one of each of the wGα (line 1.1) and cGα (line 2.1) lines for further analysis, and these two lines will be referred to as wGα and cGα, respectively.

To avoid the artificial influence of DEX described previously (Kang et al., 1999), we applied various concentrations of DEX to the transgenic plants and examined their phenotypes under these conditions. False traits, such as a stunted root and half-closed cotyledons at the seedling stage, were observed regularly at DEX concentrations greater than 1 μM and also were observed in the empty vector control plants. To avoid the false phenotype, we routinely used DEX concentrations between 10 and 100 nM. Within this range of DEX concentrations, we observed no false phenotypes in our selected transgenic lines or in wild-type seedlings (data not shown). The optimum concentration of DEX for each line was decided on the basis of the level of Gα protein expression.

wGα and cGα Lines Overexpress Gα Protein by DEX Induction

Both wGα and cGα lines grown in the presence of DEX (30 nM for wGα and 70 nM for cGα; see Methods) overexpressed the Gα protein. The wGα and cGα seedlings grown on plates with these concentrations of DEX had increased levels of Gα protein relative to the empty vector control transgenic line (VE) and wild-type seedlings both in darkness and under continuous white light (Figures 1A and 1B). Under these conditions, the transgenic lines expressed at least two times more Gα protein in both wGα and cGα seedlings than did the wild type and the control VE line.

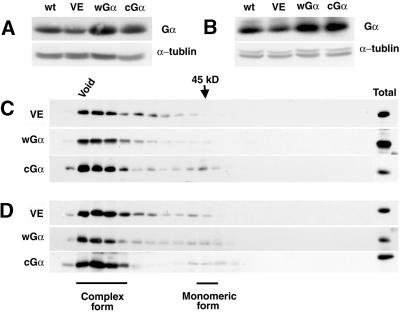

Figure 1.

Protein Blot Analysis of Gα Overexpression in Transgenic Plants.

(A) Total protein extracts (35 μg/lane) of wild-type, VE, wGα, and cGα seedlings grown for 5 days in darkness on DEX-containing plates were separated on a 10% acrylamide gel and probed with anti-Gα and anti–α-tubulin polyclonal antibodies.

(B) Total protein extracts (35 μg/lane) of wild-type, VE, wGα, and cGα seedlings grown for 5 days in the light (160 μmol·m−2·sec−1) on DEX-containing plates were separated on a 10% acrylamide gel and probed with anti-Gα and anti–α-tubulin polyclonal antibodies.

(C) Gel filtration chromatography of dark-grown seedling extracts.

(D) Gel filtration chromatography of light-grown seedling extracts.

wt, wild type.

As shown in Figure 1C, gel filtration analysis indicated that there were monomeric and complex forms in both wGα and cGα dark-grown seedlings. However, in the VE control or wild-type seedlings, the monomeric form was barely detectable (Figure 1C; data not shown). In light-grown seedlings, there was a higher ratio of monomeric versus complex form in all lines, and the monomeric form was detectable in the VE control line in the light (Figure 1D). Overall, the overexpressor lines in general had a higher monomer-to-complex ratio than the VE controls. Because the GTP binding form of Gα is thought to be a monomer, it is possible that the monomeric protein we detected in the light-grown control plants was the active Gα.

Gα Overexpressors Show Exaggerated Light Responses

When the wGα and cGα lines were grown under continuous irradiation with white light (10 μmol·m−2·sec−1) for 5 days in the presence of DEX, the hypocotyl length of these lines was reduced to ∼60% of that of the control plants (Figures 2A and 2D). However, dark-grown seedlings exhibited no significant difference between the VE control and the Gα overexpression lines (Figure 2D). Given that the dark-grown seedlings expressed as much Gα protein as the light-grown seedlings after DEX treatment (Figure 1A), these results indicate that the observed hypocotyl phenotype is light dependent.

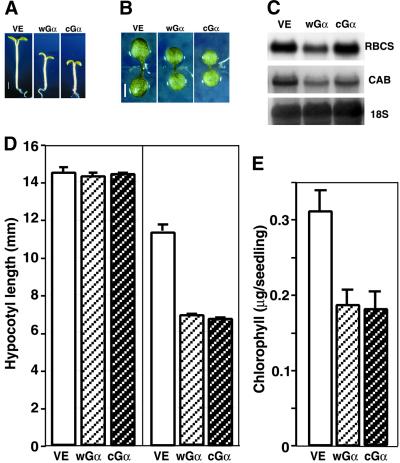

Figure 2.

Gα Overexpression Results in Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation.

(A) Photographs of representative 5-day-old VE, wGα, and cGα seedlings (left to right) grown under continuous white light irradiation (10 μmol·m−2·sec−1) in the presence of DEX. Bar = 2 mm.

(B) Representative cotyledons of VE, wGα, and cGα (left to right) seedlings grown under continuous white light irradiation (160 μmol·m−2·sec−1) for 5 days in the presence of DEX. Bar = 2 mm.

(C) CAB and RBCS expression of VE, wGα, and cGα (left to right) seedlings grown under continuous white light irradiation (12 μmol·m−2·sec−1) for 5 days in the presence of DEX.

(D) Mean hypocotyl length of 5-day-old seedlings grown in darkness (left) or continuous white light (right) irradiation (10 μmol·m−2·sec−1) in the presence of DEX.

(E) Total chlorophyll content of VE, wGα, and cGα seedlings grown under the same conditions as in (A).

Error bars represent the standard deviation.

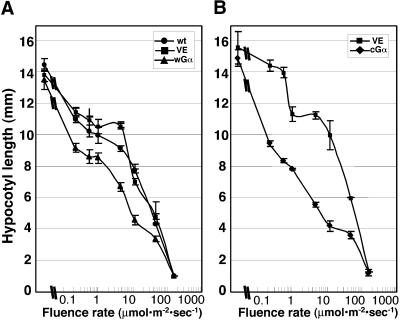

Because these transgenic lines seemed to have increased sensitivity to light, we examined their hypocotyl elongation responses to a range of very low to high fluence light. The wGα and cGα lines were sown on plates containing 30 and 70 nM DEX, respectively (these concentrations give a similar amount of Gα overexpression) (Figures 1A and 1B). When these plants were exposed to very low fluence light, both wGα and cGα seedlings started to show increased reduction in hypocotyl length compared with the VE control and the wild type. The fluence response curves of both wGα and cGα lines were steeper than those of the control plants in the low light range. The differences between the wild-type, control VE, and Gα transgenic plants gradually became smaller when a higher intensity of light was applied, and the differences were no longer detectable at a light fluence of 160 μmol·m−2·sec−1 (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Fluence Responses of Gα Overexpressor Seedlings.

(A) Fluence response curves of wGα, VE, and wild-type (wt) seedlings grown for 5 days in continuous white light on a plate containing 30 nM DEX.

(B) Fluence response curves of cGα and VE control seedlings grown for 5 days in continuous white light on a plate containing 70 nM DEX. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

Even at the maximum fluence rate (160 μmol·m−2·sec−1), at which no difference was detected between control plants and the Gα lines in terms of hypocotyl length, cotyledons of wGα and cGα lines were much smaller than those of the control (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the chlorophyll content per seedling of the Gα lines also was reduced to ∼50% of the level of the control plants under this high light fluence (Figure 2E), but the chlorophyll a/b ratios of these seedlings remained the same as in the VE control (data not shown). This reduction of chlorophyll content correlated with small cotyledons, which may contain fewer cells or smaller cells with fewer chloroplasts. The transcript levels of light-induced genes such as CAB and RBCS were slightly lower in the Gα-overexpressing plant than in the VE control (Figure 2C).

The Short Hypocotyl Phenotype of Gα Overexpression Lines Is a Result of Reduced Hypocotyl Cell Elongation

The smaller cotyledons and shorter hypocotyls in the Gα lines relative to the control VE line could be a result of a reduced number of cells on the hypocotyl or an effect on cell elongation. Because Arabidopsis seedling development is completed in embryogenesis during seed maturation, the number of cells per seedling would be predetermined. It has been reported that epidermal or cortical cell divisions are insignificant for Arabidopsis hypocotyl elongation in dark- and light-grown seedlings (Gendreau et al., 1997). To determine whether the Gα overexpressor lines had affected hypocotyl cell elongation or cell division, we counted the number of hypocotyl epidermal cells of both Gα lines and the control seedlings grown for 5 days under white light (10 μmol· m−2·sec−1). The light-grown Arabidopsis hypocotyl epidermis consists of two distinct files of mostly alternating cells (Gendreau et al., 1997). One type of file contains larger and more protruding cells, whereas the other, which is made up of burrowed cells, lies between the protruding cell files (see scheme of the transverse section of hypocotyl cells in Figure 4A). Stomata structures are found only in burrowed cell files, and there is no noticeable cell differentiation in the protruding cell files.

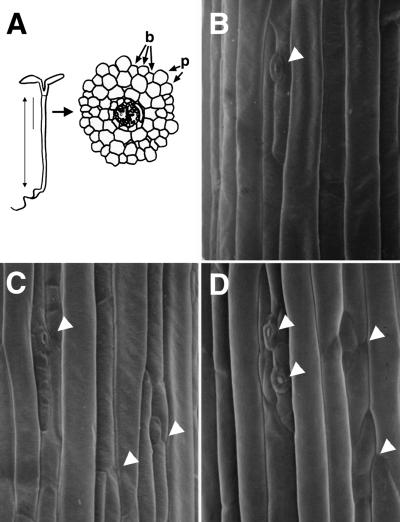

Figure 4.

Stomata Cell Differentiation in the Hypocotyl Epidermis.

(A) Scheme of an Arabidopsis seedling and a transverse section of a hypocotyl. The double-headed arrow shows the region in which hypocotyl cells were counted. The solid line shows the region in which stomata cells were observed and counted, and cells from this region are shown in (B) to (D). b, burrowed cells; p, protruding cells.

(B) Scanning electron microscopy image of the upper hypocotyl cells of a 5-day-old VE seedling.

(C) Scanning electron microscopy image of the upper hypocotyl cells of a 5-day-old wGα overexpressor seedling.

(D) Scanning electron microscopy image of the upper hypocotyl cells of a 5-day-old cGα overexpressor seedling.

The seedlings shown in (B) to (D) were grown under continuous white light (10 μmol·m−2·sec−1). The seedlings of the VE line (B) and the cGα line (D) were grown in the presence of 70 nM DEX, and the wGα line (C) was grown in the presence of 30 nM DEX. White arrowheads indicate stomatal structures.

The hypocotyl epidermis of the seedlings used for the measurement of hypocotyl length (Figure 2C) were peeled, and the cells of the protruding files were observed under a light microscope. The seedlings close to the average hypocotyl length of each line were used for cell counting. We observed 20.5 ± 1.7 (n = 15) cells in wGα, 21.7 ± 2.0 (n = 15) cells in cGα, and 22.3 ± 1.7 (n = 12) cells in control VE seedlings in the presence of DEX. The cell numbers of the protruding cell files between these lines were essentially the same, although there was a nearly twofold difference in the hypocotyl length (Figures 2A and 2C). These cell numbers are similar to those reported previously for Arabidopsis seedlings (Gendreau et al., 1997). Therefore, we conclude that there is no significant difference between the Gα lines and the control seedlings in terms of the number of protruding epidermal cells in the hypocotyl and that the reduction of hypocotyl length observed was caused by a reduction of cell elongation in the Gα seedlings.

Gα Lines Have an Increased Number of Stomata in the Hypocotyl Epidermis

We also observed a greater degree of stomatal differentiation on burrowed cell files of the hypocotyl epidermis in Gα-induced lines compared with those of the control plants (Figures 4B, 4C, and 4D). The average number of stomata structures per burrowed cell file was 5.0 ± 1.1 (n = 10) in the wGα line, 5.5 ± 0.7 (n = 10) in the cGα line, and 1.1 ± 0.3 (n = 10) in the control line. One factor known to stimulate stomatal differentiation is ethylene (Serna and Fenoll, 1997). It is possible that the increased level of Gα influenced the phytohormone balance in these plants. Another factor reported to affect stomatal differentiation is light. The frequency of stomata is usually higher in plants grown in high photon flux density than in plants grown in shade (Willmer and Fricker, 1996). Thus, this high frequency of stomata differentiation in Gα-induced lines could be a result of an exaggerated light response caused by the overexpression of Gα.

Gα Overexpression Does Not Affect the Gibberellic Acid Stimulation of Hypocotyl Elongation

It has been reported that the Gα knockout and the Gα antisense expressors of rice have a dwarf phenotype and are insensitive to the exogenous application of gibberellin (Ashikari et al., 1999; Fujisawa et al., 1999; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2000). Although generating the loss-of-function rice Gα mutants and our Gα overexpression mutant results in opposite effects at the genetic level, the phenotype of these two plants is similar. It is known that gibberellin is produced more actively in the apical meristem of light-grown plants than in that of dark-grown plants. It is possible that the light-dependent short-hypocotyl phenotype could be a consequence of insensitivity to this hormone produced in the light.

To determine whether the overexpression of Gα in Arabidopsis causes insensitivity to gibberellin, we applied gibberellic acid (GA3) to the cGα overexpressor in the presence of DEX (Figure 5B). An increase in hypocotyl length was detected in both controls and the cGα line, and the extent of this increase was indistinguishable in all lines. In the absence of DEX, the phenotype of the cGα transgenic seedlings also was indistinguishable from that of the wild type and the VE control (Figure 5A). The response of the wGα line to GA3 was similar to that of the cGα line (data not shown). This result indicates that the Gα overexpressors retain the full capacity to respond to GA3.

Figure 5.

Responsiveness of the Gα Overexpressors to Exogenous Application of GA3.

(A) The wild type, VE, and cGα, phyB, and gai mutants were grown in the absence or presence of 50 μM GA3 on plates containing DEX. The plants were grown under continuous white light (46 μmol·m−2· sec−1) for 6 days, and hypocotyl lengths were measured.

(B) The wild type, VE, and cGα were grown in the absence or presence of 50 μM GA3 without DEX in the medium.

(C) Mean hypocotyl lengths of seedlings grown under continuous B (1.8 μmol·m−2·sec−1), R (8.9 μmol·m−2·sec−1), or FR (13.2 μmol· m−2·sec−1) light for 5 days.

wt, wild type.

Error bars represent the standard deviation.

Although the loss-of-function rice Gα mutants and our Gα overexpression (gain-of-function) mutants are opposite in nature, both of them exhibited dwarf phenotypes, albeit at distinct stages. It is not clear why there is this difference between rice and Arabidopsis in their G-protein involvement in gibberellin response. It is possible that either the distinct species or the developmental stages examined may be responsible for the observed inconsistency.

The Gα Overexpressors Affect the Blue (B), R, and FR Light–Mediated Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation

We then analyzed the wGα and cGα lines under narrow wavelengths of blue (B), R, or FR light to examine whether the light-dependent Gα phenotype is dependent on a specific photoreceptor. The plants were grown under continuous irradiation with each light source for 5 days on DEX plates. Under the light conditions we used (B, 1.8 μmol·m−2· sec−1; R, 8.9 μmol·m−2·sec−1; FR, 13.2 μmol·m−2·sec−1), both lines showed a shorter hypocotyl phenotype relative to the control plants under all three light conditions (Figure 5C). These results suggest that Gα modulates signals from both B light receptors and R/FR light receptor phytochromes. Because microinjection studies using tomato seedlings indicated that the heterotrimeric G-protein may act downstream of phyA and phyB photoreceptors (Neuhaus et al., 1993; Kunkel et al., 1996), we analyzed the effect of Gα overexpression on phyA, phyB, and CRY1 signal transduction.

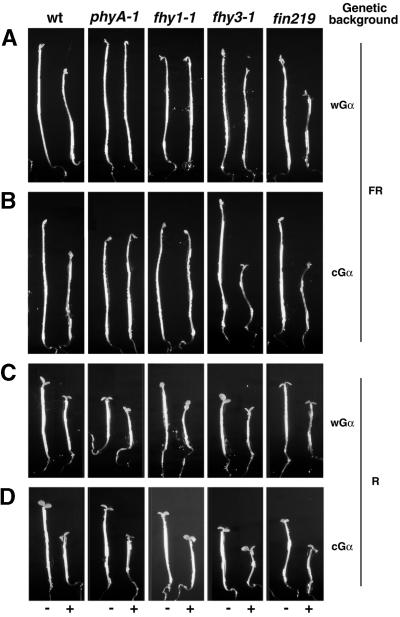

Gα Overexpressors Required Functional phyA for Their Enhancement of the FR Light–Mediated Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation

To examine the role of Gα in phyA signal transduction, we first examined its dependence on the phyA receptor. Both types of Gα-inducible lines were crossed to the phyA null mutant independently, and plants homozygous for the phyA mutation carrying the transgenes were obtained. If an input from the photoreceptor is required to generate the Gα overexpression phenotype, phyA must be required to obtain the exaggerated hypocotyl reduction phenotype in FR light. If this hypothesis is correct, Gα overexpression in the phyA mutant background would not show a hypocotyl reduction under FR light. Indeed, neither of the Gα lines in the phyA null mutant background exhibited the typical Gα-induced exaggeration of hypocotyl inhibition under FR light (Figures 6A and 6B).

Figure 6.

Dependence of the Gα Overexpression Phenotype on the phyA Signaling Pathway.

(A) Representative seedlings of the wGα line with the genetic backgrounds indicated at the top, grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 30 nM DEX, were exposed to 3-min pulses of FR light (16 μmol·m−2·sec−1) given hourly for 5 days.

(B) Representative seedlings of the cGα line with the genetic backgrounds indicated at the top, grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 70 nM DEX, were exposed to 3-min pulses of FR light (16 μmol·m−2·sec−1) given hourly for 5 days.

(C) Representative seedlings of the wGα line with the genetic backgrounds indicated at the top, grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 30 nM DEX, were exposed to 3-min pulses of R light (16 μmol·m−2·sec−1) given hourly for 5 days.

(D) Representative seedlings of the cGα line with the genetic backgrounds indicated at the top, grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 70 nM DEX, were exposed to 3-min pulses of R light (16 μmol· m−2·sec−1) given hourly for 5 days.

The seedlings were grown on plates containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium (in Mes/KOH buffer, pH 5.8) without sucrose. wt, wild type.

Gα Could Be Involved in a Branch of the phyA-Mediated FR Light Signal Transduction Pathway

To investigate the relationship of Gα to the downstream events of phyA signal transduction, we also crossed the Gα-inducible lines to three representative downstream signaling mutants (fhy1-1, fhy3-1, and fin219). It has been shown that the phyA signal transduction mutants fhy3-1 and fhy1-1 define a branch point in the phyA signaling pathway and are defective in subsets of FR light responses (Barnes et al., 1996; Yanovsky et al., 2000). Interestingly, we detected no Gα overexpression effect in the fhy1-1 background under FR light. However, we observed a normal Gα overexpression effect in both the fhy3-1 and fin219 backgrounds. Our results suggest that the Gα overexpression phenotype requires a functional phyA receptor as well as FHY1, but that it does not require FHY3 or FIN219. This finding indicates that Gα may be involved in only a branch of the phyA signaling pathway.

The Gα-overexpressing seedlings in all mutant backgrounds, including phyA and fhy1-1, showed the exaggerated reduction of hypocotyl response under R light (Figures 6C and 6D). This finding indicates that the Gα overexpression phenotype under R light requires neither phyA nor FHY1. In other words, under R light, Gα most likely interacts with a pathway that does not require phyA or FHY1.

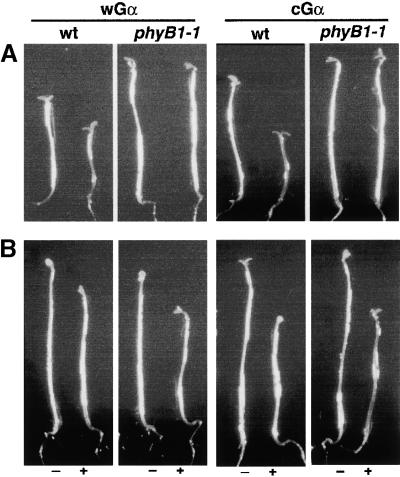

Gα Overexpressors Required Functional phyB for Their Enhancement of the R Light–Mediated Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation

To determine whether phyB is required for the observed enhancement of R light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation caused by the Gα overexpressors, we crossed the transgenes into a phyB mutant background. As shown in Figure 7A, the Gα overexpression phenotype under R light was not present in the phyB mutant background. Therefore, the phyB receptor is needed for the effect of the Gα overexpressors on the R light–mediated inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. It is important to note that both wGα and cGα in the phyB background still manifest the Gα overexpression effect under FR light (Figure 7B), indicating that phyB is not involved in the corresponding FR effect of the Gα overexpressors.

Figure 7.

The Effect of Gα Overexpression on R Light Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation Requires Functional phyB.

(A) Representative seedlings of the Gα overexpressor lines in the phyB mutant background were grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX and exposed to 3-min pulses of R light (16 μmol·m−2·sec−1) given hourly for 5 days. The DEX concentrations used for wGα and cGα seedlings were 30 and 70 nM, respectively.

(B) Representative seedlings of the Gα overexpressor lines in the phyB mutant background were grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX and exposed to 3-min pulses of FR light (16 μmol·m−2·sec−1) given hourly for 5 days. The DEX concentrations used for wGα and cGα seedlings were 30 and 70 nM, respectively.

The seedlings were grown on plates containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium (in Mes/KOH buffer, pH 5.8) without sucrose. wt, wild type.

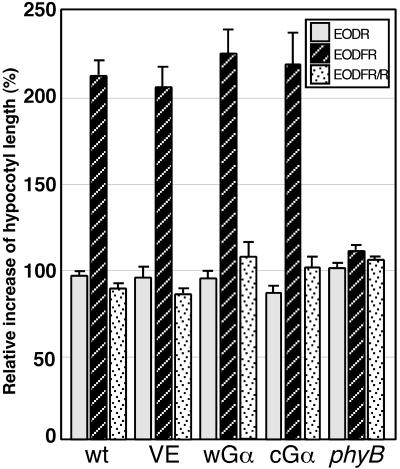

Gα Overexpression Does Not Affect phyB-Mediated End-of-Day FR Response

We also examined a second phenomenon that is regulated primarily by phyB: the end-of-day FR (EODFR) response. The results shown in Figure 8 indicate that both Gα lines retain the EODFR light–dependent stimulation of hypocotyl elongation. The rate of EODFR light–stimulated hypocotyl elongation in Gα lines was equivalent to that in the control plants, indicating that these seedlings retain the capacity to increase their hypocotyl length after EODFR treatment. The effect of the EODFR treatment could be reversed completely with an R light pulse applied immediately after the EODFR light treatment, regardless of the presence of Gα overexpression. This result also suggests that Gα is not involved in this phyB-mediated developmental response.

Figure 8.

The EODFR Response in Gα-Overexpressing Lines.

Seed were sown on plates containing DEX and were grown under 8-hr-white light (160 μmol·m−2·sec−1)/16-hr-dark cycles for 2 days. Each plate was then treated with R light (5 min; 50 μmol·m−2·sec−1) and/or FR light (5 min; 50 μmol·m−2·sec−1) at the end of the 8-hr-light cycle for 3 additional days. The hypocotyl lengths were measured, and the relative increases in hypocotyl length were calculated by comparison with control plates that had received no EODFR treatment. wt, wild type.

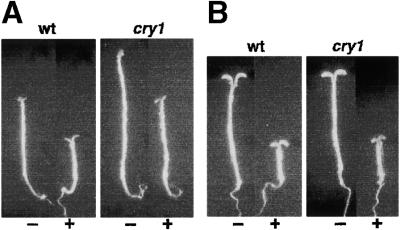

Gα Overexpression Does Not Affect CRY1-Mediated B Light Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation

To test the role of cryptochromes, the wGα transgene was crossed into cry1, a B light receptor mutant background, and its involvement in CRY1-mediated light signal transduction was examined. cry1 seedlings overexpressing Gα had short hypocotyls in B and FR light (Figure 9). This result indicates that the Gα signaling pathway is not involved in the B light receptor CRY1 pathway. It is possible that Gα might be used to modulate other photoreceptors responsible for the B light effect.

Figure 9.

The Effect of Gα Overexpression on B Light Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation Does Not Require Functional CRY1.

(A) Representative seedlings of the wGα overexpressor line in the wild-type (left) and the cry1-304 mutant (right) background were grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX and exposed to continuous B light irradiation (5 μmol·m−2·sec−1) for 5 days. The DEX concentration used for wGα was 30 nM.

(B) Representative seedlings of the wGα overexpressor line in the wild-type (left) and the cry1-304 mutant (right) background were grown in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX and exposed to continuous FR light irradiation (16 μmol·m−2·sec−1) for 5 days. The DEX concentration used for wGα was 30 nM.

The seedlings were grown on plates containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium (in Mes/KOH buffer, pH 5.8) without sucrose. wt, wild type.

DISCUSSION

Here we present genetic evidence that supports a role for the Arabidopsis heterotrimeric Gα protein in modulating phytochrome-mediated light regulation of hypocotyl elongation during seedling development. Significantly, the enhancement of FR and R light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation by conditional Gα overexpression depends entirely on functional phyA and phyB photoreceptors, respectively.

Gα May Be Involved in Branches of the phyA and phyB Signaling Pathways

We crossed the Gα-inducible lines (both wGα and cGα) to phytochrome signaling mutants (fhy1-1, fin219, and fhy3-1) as well as to a phyA null mutant and examined the effect of the Gα overexpression on phyA signal transduction. The phenotype of the Gα-overexpressing phyA seedlings was identical to that of the phyA mutant (Figures 6A and 6B), indicating that the phyA mutation prevented Gα from overactivating the FR light–dependent signaling pathway. It is known that the fhy1-1 mutant is blocked in only a subset of phyA-mediated responses at the physiological level (Johnson et al., 1994). It also is deficient in the regulation of only a subset of genes such as CHS, with CAB gene expression remaining relatively unaffected in FR light (Barnes et al., 1996). Therefore, it was proposed that fhy1-1 may define a component of the cyclic GMP–dependent pathway that regulates CHS (Barnes et al., 1997).

Recent physiological studies also have supported the idea that FHY1 and FHY3 may act in discrete pathways downstream of phyA (Yanovsky et al., 2000). Interestingly, as with the phyA mutant background, overexpression of Gα no longer conferred the increased hypocotyl reduction phenotype in the fhy1-1 mutant background (Figure 6). This finding suggests that fhy1-1 has a defect in the same signal transduction pathway in which Gα is involved. In contrast to the phyA and fhy1-1 mutants, two other phyA signal transduction mutations (fin219 and fhy3-1) did not block the phenotype caused by Gα overexpression (Figure 6). It seems likely that the active Gα is involved in the pathway defined by FHY1 in mediating FR light responses (Figure 10A). The relationship between the Gα protein and FHY1 in this pathway—that is, the hierarchy of these molecules in this signaling process—is not clear. This will be an immediate question for future investigation.

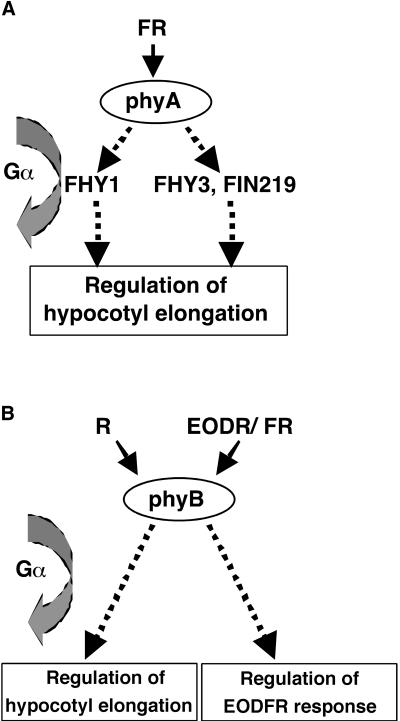

Figure 10.

Schemes of Gα Interaction with phyA and phyB Signal Transduction.

(A) The FR light signaling pathway mediated by phyA branches after photoperception. The heterotrimeric G-protein is involved in the pathway defined by FHY1 but not in the pathway that requires FHY3 and FIN219.

(B) phyB mediates R light–dependent hypocotyl regulation and the EODFR response. The heterotrimeric Gα protein is involved in the R light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation but not in the EODFR response.

As was seen with the phyA mutant in FR light, Gα overexpression did not exhibit its phenotypic effect under R light in the phyB mutant background (Figure 7). This result indicates that phyB is essential for the Gα overexpression phenotype in R light. However, Gα overexpression had no effect on the EODFR response. This suggests that Gα most likely is not involved in this phyB-mediated response. Again, the heterotrimeric G-protein regulates only a subset of phyB-mediated responses (Figure 10B).

It is important to note that our gain-of-function studies do not allow an assessment of whether the Gα protein is part of the phyA signaling cascade. They only suggest that excess Gα protein could enhance the signal propagation for specific phyA- and phyB-mediated responses. Future studies with Arabidopsis Gα protein loss-of-function mutants will be required.

Gα Overexpression May Result in More G-Protein Activity in Arabidopsis Seedlings

The gel filtration data showed that there is a higher ratio of monomeric to complex Gα in light-grown VE control seedlings compared with seedlings grown in darkness (Figure 1D). Because the GTP binding form of Gα is thought to be a monomer, it is possible that the monomeric protein we detected in light-grown plants could be active Gα. In both wGα- and cGα-overexpressing seedlings, there were notable increases of the monomeric Gα protein under both dark and light growth conditions. Although more monomeric Gα in light-grown seedlings would be consistent with an enhanced light response, the increased monomeric Gα protein detected in the dark-grown Gα overexpressor seedlings did not result in any phenotypic consequences. Perhaps this excess amount of Gα cannot function in the regulation of hypocotyl elongation. It is possible that the monomeric forms we detected in Gα-overexpressing plants in darkness represent a pool of Gα that is not yet associated with the membrane and thus cannot be activated by an upstream signal. On the other hand, our data indicate that the effect of Gα on hypocotyl elongation requires functional photoreceptors and thus Gα activation. It is possible that the presence of active Gα in darkness would not be able to elicit any physiological effect without activated photoreceptors and their associated downstream signaling processes.

It is well documented that, in general, the activation of G-protein–coupled protein receptors initiates the dissociation of the heterotrimeric G-protein complex into a GTP-bound Gα subunit and a Gβγ complex and that each of these in turn binds and activates target enzymes, generating intracellular messengers. Significantly, the conformation of free Gβγ is identical to that of Gβγ in the heterotrimer, suggesting that Gα inhibits the interaction of Gβγ with its effectors or target molecules through the Gα binding site on Gβγ (Hamm, 1998). The crystal structure of the complex form of Gα and one of its effectors, adenylate cyclase, showed that the Gα activation site for the adenylate cyclase also is the site facing the Gβγ complex during the formation of the heterotrimeric G-protein complex (Bourne, 1997). Therefore, the active sites of both the Gα monomer and the Gβγ complex are suppressed by the formation of a trimer between these proteins. In this sense, both the Gα monomer and the Gβγ complex could be considered potentially active forms of the trimeric G-protein. Therefore, another possible explanation for the overexpressed Gα phenotype in the light would be the availability of the other subunits of the heterotrimer. It is possible that the dissociated Gβγ complex might be the active regulator for hypocotyl cell elongation.

Although the phenotypic difference between the wGα and cGα lines is not dramatic, cGα seedlings were consistently shorter than wGα seedlings (data not shown). Given that the overexpression levels of wGα and cGα were similar, as demonstrated by protein gel blot analysis, the overexpressed cGα might be more active than wGα. This effect could be attributable to the increased availability of the GTP-bound monomeric form of Gα caused by the constitutively active mutant of the cGα protein.

A Possible Mechanism of Heterotrimeric G-Protein Activation through Phytochrome

In general, heterotrimeric G-proteins are activated by seven transmembrane G-protein–associated receptors. phyA and phyB are not membrane-bound or membrane-associated proteins. How could the phytochrome signal be coupled to the heterotrimeric G-protein?

By immunocytochemical and biochemical means, some phyA in the Pfr form has been found sequestered in membrane structures (reviewed in Kendrick and Kronenberg, 1994). It is possible that the Pfr form can be directed to the membrane upon activation and activate heterotrimeric G-proteins on the membrane. It was suggested that in Dictyostelium, G-protein activation is mediated by receptor-stimulated nucleoside diphosphate (NDP) kinase (Bominaar et al., 1993). Therefore, the NDP kinase 2 (NDPK2) that was found in a yeast two-hybrid assay to interact with phyA (Choi et al., 1999) could be a potential activator of the heterotrimeric G-protein when it is activated by photoreceptors. This is consistent with the fact that the active Pfr form of phyA interacts with NDPK2 to a significantly greater degree than does the R light–absorbing form. Considering the relatively insoluble nature of the Pfr form, NDPK2 might be recruited to the membrane by phytochrome upon activation. In support of this idea, R light–dependent phosphorylation of NDP kinase has been reported in pea (Tanaka et al., 1998). It is possible that phytochrome-dependent activation of NDP kinase that is sequestered by phytochrome to the membrane might activate G-proteins by increasing the level of GTP in their vicinity. This raises the possibility that G-proteins might interact directly with either phytochrome or NDPK2.

METHODS

Plant Material and Construction of Transgenic Plants

A cDNA library was generated from RNA isolated from 1-week-old seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia. The wild-type Gα cDNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction using this cDNA library as a template with gene-specific primers (5′-CTCGAGATGGGCTTACTCTGCAGTAGAA-3′ and 5′-ACTAGTTCATAAAAGGCCAGCCTCCAGTA-3′) complementary to regions encoding the N and C termini of the protein. The constitutively active form of Gα was generated by changing Glu-222 to Leu by polymerase chain reaction–based mutagenesis using primers 5′-TGACGTGGGTGGACTGAGAAATGAGAGGAGG-3′ and 5′-CCTCCTCTCATTTCTCAGTCC-ACCCACGTCA-3′ in combination with the primer sets used to amplify Gα cDNA. These fragments were inserted into XhoI and SpeI sites in the pTA7002 vector (Aoyama and Chua, 1997) and transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3011, which was used to transform Arabidopsis. The ecotype Wassilewskija was used for plant transformation; the same ecotype was transformed with the empty vector as the control. The transformants were selected for their hygromycin resistance, and the surviving seedlings were transferred to soil to obtain seed. In the next generation, the lines that segregated 25% hygromycin-sensitive seedlings (single locus lines) were selected for further analysis.

Finally, one line each from the wild type (wGα) and the constitutively active type (cGα) were selected for further biochemical and physiological analyses. For genetic crosses into photomorphogenic mutants, the phyA photoreceptor mutant phyA-101 as well as the phytochrome signal transduction mutants fhy1-1, fhy3-1, and fin219 were used. The phyA mutant is in the Nossen background, fhy1 is in Landsberg, and fhy3-1 and fin219 are in the Columbia ecotype. The phyB mutant is in the Landsberg background, and cry1-304 is in the Columbia background. Examination of multiple F2 progeny from these crosses indicated that the background ecotypes did not exhibit observable effects on the transgene phenotypes.

Plant Growth Conditions

Seed were surface sterilized and kept at 4°C in darkness for 1 day. The seed were sown on plates containing 0.8% agarose, 1% sucrose, 1 × Murashige and Skoog (1962) salts with vitamin mixture (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD), and 0.05% Mes; pH was adjusted with KOH to pH 5.8 unless stated otherwise. A water-soluble form of dexamethasone (DEX; Sigma) was added to the plates in the range of 10 to 100 nM. For the two lines selected for extensive analysis, optimal DEX concentrations (wGα, 30 nM; cGα, 70 nM) were determined and used throughout the studies. Control plants were sown on the same plates for both DEX concentrations. Because there was no significant difference between phenotypes of control plants grown on 30 and 70 nM DEX plates, all of the control data shown in the figures were taken from the 70 nM plates. The seed sown on the agar plates were kept at 4°C in darkness for 2 to 3 days and were exposed to continuous white light for 24 hr to initiate germination, unless stated otherwise.

Light Sources

Monochromatic blue, far-red (FR), and red (R) light were obtained by light-emitting diodes (model E-30; Percival Scientific, Boone, IA) at peak wavelengths of 470, 669, and 739 nm, respectively, with a half-bandwidth of 10 nm. The FR light source was covered with a plexiglass filter (FRF 700; Westlake Plastics, Lenni, PA) to eliminate any residual R light (<700 nm). Various fluences of dim white light were provided by covering the plates with filter papers (Whatman 3 MM chromatography paper) under the light provided by fluorescent tube (TL70, F17T8/TL741; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). The green safelight used in the biochemical analysis was obtained by wrapping a green fluorescent tube (GTE Sylvania F40G) with a layer of blue filter (Lee filter HT116; Lee Colotran, Inc., Totowa, NJ) and a layer of green filter (Lee filter 119).

Chlorophyll Assays

Seedlings were ground in darkness in a solution containing 10 mM Tris HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, and chlorophylls were extracted with acetone (1:4, v/v). The amounts of chlorophyll a and b were determined using MacKinney's coefficients (MacKinney, 1941) and the equations chlorophyll a = 12.7 (A663) − 2.69 (A645) and chlorophyll b = 22.9 (A645) − 4.48 (A663).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Seedlings were fixed with 10% formaldehyde, 10% acetic acid, and 30% ethanol for 1 hr at room temperature and subjected to a dehydration process with ethanol. They were then subjected to a critical drying process and spattered with tungsten particles, and a scanning electron microscope was used to observe the hypocotyl epidermal cells. Seedlings also were observed with the light microscope using differential interference to count hypocotyl cell numbers.

Protein and RNA Gel Blot Analyses

All of the protein gel blot samples were separated on 10% acrylamide gels containing SDS. A polyclonal anti-Gα antibody used to detect the Gα protein was raised against a synthetic oligopeptide corresponding to the C-terminal sequence of GPA1, and protein gel blotting was performed according to the method described by Weiss et al. (1993). The primary antibody was probed with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody, and the signal was detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham-Pharmacia). For detection of the loading control, α-tubulin antibody (Sigma) was used to hybridize the same membrane used for Gα detection according to the conditions recommended by the manufacturer.

RNA isolation and RNA gel blot analysis were performed according to our previously described protocols (Torii et al., 1999). The same probes (CAB and RBCS) and labeling method (Torii et al., 1999) were used in this work.

Gel Filtration Chromatography

Seedlings were ground in a buffer containing 30 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 330 mM sucrose, 2.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM DTT, and 1 × complete proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Boehringer Mannheim) and centrifuged at 16,000g at 4°C for 10 min. GTP was added to the supernatant at a final concentration of 10 μM, and samples were centrifuged at 6000g at 4°C for 5 min to further eliminate any precipitated material. Triton X-100 was added to the supernatant at a final concentration of 0.5%, and samples were centrifuged at 120,000g at 4°C for 30 min to remove the microsomal membranes. The supernatant was loaded onto a Superdex 75 gel filtration column (Amersham-Pharmacia). Gel filtration was performed with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8, at 4°C, 150 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol, and protein fractions of 250 μL were collected. Protein in each fraction was concentrated by adding 10 μL of resin (StrataClean; Stratagene), and 2 × SDS sample buffer was added to each of the resins before loading onto acrylamide gels.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

During the review process of this paper, a related paper describing Arabidopsis GPA knock-out lines was reported. Ullah, H., Chen, J.-G., Young, J.C., Im, K.-H., Sussman, M.R., and Jones, A.M. (2001). Modulation of cell proliferation by G-protein alpha subunits in Arabidopsis. Science, in press.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barry Piekos for help with scanning electron microscopy, Jie Liu for technical assistance, and Drs. Christian Hardtke, Magnus Holm, and Matthew Terry for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Human Frontier Science Program Grant RG0043/97 (to X.W.D. and M.M.) and by National Institutes of Health Grant GM47850 (to X.W.D.). X.W.D. is a National Science Foundation Presidential Faculty Fellow.

References

- Aharon, G., Gelli, A., Snedden, W.A., and Blumwald, E. (1998). Activation of a plant plasma membrane Ca2+ channel by TGα1, a heterotrimeric G protein α-subunit homologue. FEBS Lett. 424, 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama, T., and Chua, N.-H. (1997). A glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional induction system in transgenic plants. Plant J. 11, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. (2000). Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashikari, M., Wu, J., Yano, M., Sasaki, T., and Yoshimura, A. (1999). Rice gibberellin-insensitive dwarf mutant gene Dwarf1 encoded the α-subunit of GTP-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9207–9211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, S.M. (1996). Guard cell G proteins. Trends Plant Sci. 1, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S.A., Quaggio, R.B., Whitelam, G.C., and Chua, N.-H. (1996). fhy1 defines a branch point in phytochrome A signal transduction pathways for gene expression. Plant J. 10, 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S.A., McGrath, R.B., and Chua, N.-H. (1997). Light signal transduction in plants. Trends Cell Biol. 7, 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolle, C., Koncz, C., and Chua, N.-H. (2000). PAT1, a new member of the GRAS family, is involved in phytochrome A signal transduction. Genes Dev. 14, 1269–1278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bominaar, A.A., Molijn, A.C., Pestel, M., Veron, M., and Van Haastert, P.J.M. (1993). Activation of G-proteins by receptor-stimulated nucleoside diphosphate kinase in Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 12, 2275–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, H.R. (1997). Enhanced: Pieces of the true grail. A G protein finds its target. Science 278, 1898–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, C., Neuhaus, G., Yamagata, H., and Chua, N.-H. (1994). Cyclic GMP and calcium mediate phytochrome phototransduction. Cell 77, 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, G., Yi, H., Lee, J., Kwon, Y.-K., Soh, M.S., Shin, B., Luka, Z., Hahn, T.-R., and Song, P.-S. (1999). Phytochrome signalling is mediated through nucleoside diphosphate kinase 2. Nature 401, 610–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild, C.D., Schumaker, M.A., and Quail, P.H. (2000). HFR1 encodes an atypical bHLH protein that acts in phytochrome A signal transduction. Genes Dev. 14, 2377–2391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C., and Chory, J. (2000). RSF1, an Arabidopsis locus implicated in phytochrome A signaling. Plant Physiol. 124, 39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C., Yeh, K.-C., Lagarias, J.C., Zhang, H., Elich, T.D., and Chory, J. (1999). PKS1, a substrate phosphorylated by phytochrome that modulates light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science 284, 1539–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa, Y., Kato, T., Ohki, S., Ishikawa, A., Kitano, H., Sasaki, T., Asahi, T., and Iwasaki, Y. (1999). Suppression of the heterotrimeric G protein causes abnormal morphology, including dwarfism, in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 7575–7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendreau, E., Traas, J., Desnos, T., Grandjean, O., Caboche, M., and Höfte, H. (1997). Cellular basis of hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 114, 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, H.E. (1998). The many faces of G protein signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoecker, U., Tepperman, J.M., and Quail, P.H. (1999). SPA1, a WD-repeat protein specific to phytochrome A signal transduction. Science 284, 496–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, S.-L., Okamoto, H., Wang, M., Ang, L.-H., Matsui, M., Goodman, H., and Deng, X.W. (2000). FIN219, an auxin-regulated gene, defines a link between phytochrome A and the downstream regulator COP1 in light control of Arabidopsis development. Genes Dev. 14, 1958–1970. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H., Weiss, C.A., and Ma, H. (1994). Regulated expression of the Arabidopsis G protein α subunit gene GPA1. Int. J. Plant Sci. 155, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, M., Ringli, C., Boylan, M.T., and Quail, P.H. (1999). The FAR1 locus encodes a novel nuclear protein specific to phytochrome A signaling. Genes Dev. 13, 2017–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E., Bradley, M., Harberd, N.P., and Whitelam, G.C. (1994). Photoresponses of light-grown phyA mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 105, 141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H.D., Smith, S.J., Desikan, R., Plakidou-Dimock, S., Lovesgrove, A., and Hooley, R. (1998). Heterotrimeric G proteins are implicated in gibberellin induction of α-amylase gene expression in wild oat aleurone. Plant Cell 10, 245–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.-G., Fang, Y., and Singh, K.B. (1999). A glucocorticoid-inducible transcription system causes severe growth defects in Arabidopsis and induces defense-related genes. Plant J. 20, 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, R.E., and Kronenberg, G.H.M. (1994). Photomorphogenesis in Plants, 2nd ed. (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers).

- Kircher, S., Kozma-Bognar, L., Kim, L., Adam, E., Harter, K., Schafer, E., and Nagy, F. (1999). Light quality–dependent nuclear import of the plant photoreceptors phytochrome A and B. Plant Cell 11, 1445–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel, T., Neuhaus, G., Batschauer, A., Chua, N.-H., and Schafer, E. (1996). Functional analysis of yeast-derived phytochrome A and B phycocyanobilin adducts. Plant J. 10, 625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. (1994). GTP-binding proteins in plants: New members of an old family. Plant Mol. Biol. 26, 1611–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H., Yanofsky, M.F., and Meyerowitz, E. (1990). Molecular cloning and characterization of GPA1, a G protein α subunit gene of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 3821–3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., Xu, X., Cui, S., and Sun, D. (1999). The presence of a heterotrimeric G protein and its role in signal transduction of extracellular calmodulin in pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Cell 11, 1351–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinney, G. (1941). Absorption of light by chlorophyll solutions. J. Biol. Chem. 140, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Garcia, J., Huq, E., and Quali, P.H. (2000). Direct targeting of light signals to a promoter element–bound transcription factor. Science 288, 859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M.G., and Botella, J. (2001). Completing the heterotrimer: Isolation and characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana G protein γ-subunit cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 14784–14788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani, A., Reed, J.W., and Chory, J. (1993). Isolation and initial characterization of Arabidopsis mutants that are deficient in phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 102, 269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nern, A., and Arkowitz, R.A. (2000). G proteins mediate changes in cell shape by stabilizing the axis of polarity. Mol. Cell 5, 853–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus, G., Bowler, C., Kern, R., and Chua, N.-H. (1993). Calcium/calmodulin–dependent and –independent phytochrome signal transduction pathways. Cell 73, 937–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M., Tepperman, J.M., and Quail, P.H. (1998). PIF3, a phytochrome-interacting factor necessary for normal photoinduced signal transduction, is a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein. Cell 95, 657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrdlik, P., Neuhaus, G., and Merkle, T. (2000). Plant heterotrimeric G protein β subunit is associated with membrane via protein interactions involving coiled-coil formation. FEBS Lett. 476, 208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, B.M., and Quail, P.H. (1993). hy8, a new class of Arabidopsis long hypocotyl mutants deficient in functional phytochrome A. Plant Cell 5, 39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, J.W., Nagpal, P., Poole, D.S., Furuya, M., and Chory, J. (1993). Mutations in the gene for the red/far-red light receptor phytochrome B alter cell elongation and physiological responses throughout Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 5, 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna, L., and Fenoll, C. (1997). Tracing the ontogeny of stomatal clusters in Arabidopsis with molecular markers. Plant J. 12, 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock, R.A., and Quail, P.H. (1989). Novel phytochrome sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana: Structure, evolution, and differential expression of a plant regulatory photoreceptor family. Genes Dev. 3, 1745–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh, M.S., Hong, S.H., Hanzawa, H., Furuya, M., and Nam, H.G. (1998). Genetic identification of FIN2, a far red light-specific signaling component of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh, M.S., Kim, Y.-M., Han, S.-J., and Song, P.-S. (2000). REP1, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, is required for a branch pathway of phytochrome A signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12, 2061–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, N., Ogura, T., Noguchi, T., Hirano, H., Yabe, H., and Hasunuma, K. (1998). Phytochrome-mediated light signals are transduced to nucleotide diphosphate kinase in Pisum sativum L. cv. Alaska. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 45, 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii, K.U., Stoop-Myer, C.D., Okamoto, H., Coleman, J.E., Matsui, M., and Deng, X.W. (1999). The RING-finger motif of photomorphogenic repressor COP1 specifically interacts with the RING-H2 motif of a novel Arabidopsis protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 27674–27681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Fujisawa, Y., Kobayashi, M., Ashikari, M., Iwasaki, Y., Kitano, H., and Matsuoka, M. (2000). Rice dwarf mutant d1, which is defective in the α subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein, affects gibberellin signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11638–11643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.A., Huang, H., and Ma, H. (1993). Immunolocalization of the G protein α subunit encoded by the GPA1 gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5, 1513–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.A., Garnaat, C.W., Mukai, K., Hu, Y., and Ma, H. (1994). Isolation of cDNAs encoding guanine nucleotide-binding protein β-subunit homologues from maize (ZGB1) and Arabidopsis (AGB1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9554–9558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.A., White, E., Huang, H., and Ma, H. (1997). The G protein α subunit (GPα1) is associated with the ER and the plasma membrane in meristematic cells of Arabidopsis and cauliflower. FEBS Lett. 407, 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelam, G.C., Johnson, E., Peng, J., Carol, P., Anderson, M.L., Cowl, J.S., and Harberd, N.P. (1993). Phytochrome A null mutants of Arabidopsis display a wild-type phenotype in white light. Plant Cell 5, 757–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmer, C., and Fricker, M. (1996). Stomata. (London: Chapman and Hall), pp. 95–125.

- Yamaguchi, R., Nakamura, M., Mochizuki, N., Kay, S.A., and Nagatani, A. (1999). Light-dependent translocation of a phytochrome B-GFP fusion protein to the nucleus in transgenic Arabidopsis. J. Cell Biol. 145, 437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovsky, M.J., Whitelam, G.C., and Casal, J.J. (2000). fhy3–1 retains inductive responses of phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 123, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaal, R.R., Ahringer, J., van Luenen, H.G., Rushforth, A., Anderson, P., and Plasterk, R.H. (1996). G proteins are required for spatial orientation of early cell cleavages in C. elegans embryos. Cell 86, 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]