Abstract

Reovirus infection is initiated by interactions between the attachment protein σ1 and cell surface carbohydrate and junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A). Expression of a JAM-A mutant lacking a cytoplasmic tail in nonpermissive cells conferred full susceptibility to reovirus infection, suggesting that cell surface molecules other than JAM-A mediate viral internalization following attachment. The presence of integrin-binding sequences in reovirus outer capsid protein λ2, which serves as the structural base for σ1, suggests that integrins mediate reovirus endocytosis. A β1 integrin-specific antibody, but not antibodies specific for other integrin subunits, inhibited reovirus infection of HeLa cells. Expression of a β1 integrin cDNA, along with a cDNA encoding JAM-A, in nonpermissive chicken embryo fibroblasts conferred susceptibility to reovirus infection. Infectivity of reovirus was significantly reduced in β1-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells in comparison to isogenic cells expressing β1. However, reovirus bound equivalently to cells that differed in levels of β1 expression, suggesting that β1 integrins are involved in a postattachment entry step. Concordantly, uptake of reovirus virions into β1-deficient cells was substantially diminished in comparison to viral uptake into β1-expressing cells. These data provide evidence that β1 integrin facilitates reovirus internalization and suggest that viral entry occurs by interactions of reovirus virions with independent attachment and entry receptors on the cell surface.

Viral attachment and cell entry are key determinants of target cell selection in the infected host and thus play important roles in pathogenesis. Many viruses interact with multiple cell surface molecules to mediate the processes of attachment and internalization (68). For example, human immunodeficiency virus uses CD4 to bind the cell surface and chemokine receptors to facilitate the conformational alterations in envelope glycoproteins that culminate in fusion of the viral envelope and cell membrane (35). Receptors that serve as initial binding sites have been identified for many viruses (25). However, little is known about the postattachment events that lead to nonenveloped virus internalization, in particular those that mediate virus uptake into the endocytic pathway.

Mammalian reoviruses are large, nonenveloped, double-stranded RNA-containing viruses that infect a variety of mammalian species. Following attachment to target cells, reoviruses are internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis (3, 13, 14, 72), which is mostly likely to be clathrin dependent (31). Proteolytic disassembly in endosomes leads to removal of outer capsid protein σ3 and cleavage of outer capsid protein μ1 (3, 14, 27, 72). The resultant disassembly intermediate formed by these events, the infectious subvirion particle (ISVP), is capable of penetrating endosomal membranes in a μ1-dependent manner to release the transcriptionally active viral core particle into the cytoplasm (17, 18, 58), where viral replication takes place. Cellular determinants of reovirus receptor-mediated internalization following attachment and preceding uncoating are poorly defined.

We previously identified junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A) as a serotype-independent receptor for reovirus (5, 16, 34). JAM-A is a type 1 transmembrane protein expressed in a variety of cell types, including polarized endothelial and epithelial cells and circulating leukocytes (52, 55, 81). JAM-A interacts with several scaffolding proteins and cytoplasmic adaptor molecules (6, 28, 29) and is hypothesized to play an important role in maintaining the barrier function of epithelial junctions (48, 52, 55, 60). JAM-A is phosphorylated during platelet activation and required for mitogen-activated protein kinase activation following treatment of endothelial cells with basic fibroblast growth factor (57). These data indicate that JAM-A is intimately associated with cytoskeletal and signaling machinery, which raises the possibility that reovirus binding to JAM-A mediates cytoskeletal rearrangement or signaling events to facilitate virus internalization.

The attachment mechanisms of reovirus and adenovirus are remarkably similar (70, 71). The trimeric attachment proteins of both viruses, σ1 and fiber, respectively, are structural homologues and fold using a highly unusual triple β-spiral motif (10, 20, 83). The globular head domains of these molecules are formed from eight-stranded β-barrels with identical interstrand connectivity (70). The receptors for σ1 and fiber, JAM-A (5) and coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) (7), respectively, are two-domain, immunoglobulin superfamily proteins that form homodimers using analogous molecular surfaces (71). Also, both JAM-A and CAR localize to tight junctions in polarized epithelial cells (23, 52, 55, 60). Remarkably, reovirus and adenovirus engage their respective receptors by thermodynamically favored disruption of receptor homodimers (34, 53).

Despite mediating high-affinity attachment of adenovirus to cells, engagement of CAR does not permit efficient adenovirus internalization. Instead, adenovirus entry is enhanced by high-avidity interactions of the viral penton base complex with integrins, including αvβ3 and αvβ5 (80). Integrins are heterodimeric cell surface molecules that consist of α and β subunits (43). Integrins function to mediate cellular adhesion to the extracellular matrix, regulate cellular trafficking, and transduce both outside-in and inside-out signaling events (42). In addition to adenovirus, several other pathogenic microorganisms have usurped the adhesion and signaling properties of integrins to bind or enter host cells (1, 8, 32, 39-41, 44, 49).

To define the molecular basis of reovirus internalization, we first tested the capacity of a JAM-A mutant lacking a cytoplasmic tail to support reovirus attachment and infection. We found that while JAM-A is necessary for efficient attachment to cells, the JAM-A cytoplasmic tail is not required for reovirus infection. Given the mechanistic conservation of reovirus and adenovirus attachment strategies and the observation that reovirus outer capsid protein λ2 contains the conserved integrin-binding sequences Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) and Lys-Gly-Glu (KGE), we tested the role of integrins in reovirus internalization. We found that infection by reovirus virions is inhibited by antibodies specific for β1 integrin. In addition, cells deficient in β1 integrin have a diminished susceptibility to reovirus infection due to a postattachment block to viral entry. Together, these data indicate that, following attachment to JAM-A, β1 integrin facilitates internalization of reovirus into cells. Our findings further demonstrate that two seemingly unrelated viruses utilize distinct cellular molecules to mediate attachment and internalization in a remarkably similar manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and antibodies.

Spinner-adapted murine L929 (L) cells were grown in either suspension or monolayer cultures in Joklik's modified Eagle's minimal essential medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) supplemented to contain 5% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 U of streptomycin per ml, and 0.25 mg amphotericin per ml (Gibco Invitrogen Corp., Grand Island, NY). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were maintained in Ham's F12 medium (Irvine Scientific) supplemented to contain 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 U of streptomycin per ml. HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco Invitrogen Corp.) and supplemented as described for CHO cells. Primary cultures of chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEFs) were obtained from Paul Spearman (Vanderbilt University) and maintained in medium 199 with Earle's salts and 2.2 mg sodium bicarbonate per ml (Gibco Invitrogen Corp.) supplemented to contain 5% fetal bovine serum, 10% tryptose phosphate broth, 1% chicken serum (Gibco Invitrogen Corp.), and antibiotics as described for CHO cells. GD25 and GD25β1A cells were obtained from Deane Mosher (University of Wisconsin, Madison) (78) and maintained as described for HeLa cells. Medium for GD25β1A cells was supplemented to contain 10 μg of puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) per ml to maintain β1 integrin expression.

Reovirus strains type 1 Lang (T1L) and type 3 Dearing (T3D) are laboratory stocks. Working stocks of virus were prepared by plaque purification and passage in L cells (75). Purified virions were generated from second-passage L-cell lysate virus stocks. Virus was purified from infected cell lysates by Freon extraction and CsCl gradient centrifugation as described (36). Bands corresponding to the density of reovirus particles (1.36 g/cm3) were collected and dialyzed against virion storage buffer (150 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4]). Reovirus particle concentration was determined by the equivalence of 1 unit of optical density at 260 nm to 2.1 × 1012 particles (69).

Viral infectivity titers were determined by either plaque assay (75) or fluorescent focus assay (4). ISVPs were generated by treatment of 2 × 1011 virion particles per ml with 2 mg of α-chymotrypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) per ml in a volume of 100 μl virion storage buffer at 37°C for 30 min (2). Reactions were terminated by the addition of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride to a final concentration of 1.0 mM. Purified T1L virions in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) were fluoresceinated by incubation with 50 μg fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Pierce, Rockford, IL) per ml at room temperature for 1 h (38). Excess FITC was removed by exhaustive dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) fractions of rabbit antisera raised against T1L and T3D (79) were purified by protein A-Sepharose as previously described (4). Fluorescently conjugated secondary Alexa antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The human JAM-A (hJAM-A)-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) J10.4 and control mouse ascites were provided by Charles Parkos (Emory University School of Medicine) (52), and the murine JAM-A (mJAM-A)-specific MAb H202-106-7-4 was provided by Beat Imof (University of Geneva). The human α2-specific MAb AA10 (IgM) (8) and human β1-specific MAb DE9 (IgG1) (8) were used as diluted ascites. Human integrin-specific MAbs MAB1980 (αv), MAB1973 (α1), MAB2057 (α3), MAB1378 (α6), MAB1976 (αvβ3), and MAB1961Z (αvβ5) were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Antibody BIIG2 (α5) (Developmental Hybridoma Studies Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) was provided by John Williams (Vanderbilt University). Function-blocking human α2-specific MAb 6F1 was provided by Richard Bankert (State University of New York at Buffalo). Function-blocking murine β1 MAb CD29 (IgM) and hamster IgM isotype control were purchased from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Jose, CA). Murine β1-specific MAb MAB1997 (Chemicon) and human β1-specific MAb MAB2253Z (Chemicon) were used to assess expression of β1 integrin on GD25 and GD25β1A cells and HeLa cells, respectively, by flow cytometry. ICAM-1-specific MAb was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The antibodies used for flow cytometric analysis of HeLa cells are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Surface expression of integrins on HeLa cells

| Antibody | Specificity | Mean fluorescence intensitya |

|---|---|---|

| MAB1997 (IgG control) | Murine β1 integrin | 2.65 |

| MAB1973 | Human α1 integrin | 76.09 |

| MAB6F1 | Human α2 integrin | 84.47 |

| MAB2057 | Human α3 integrin | 73.31 |

| MABBIIG2 | Human α5 integrin | 76.68 |

| MAB1378 | Human α6 integrin | 81.86 |

| MAB1980 | Human αv integrin | 78.75 |

| MAB2253Z | Human β1 integrin | 61.14 |

| MAB1976 | Human αvβ3 integrin | 5.46 |

| MAB1961Z | Human αvβ5 integrin | 42.10 |

Results are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity for an average of 14,000 gated events as assessed by flow cytometry.

Sequence analysis.

The sequences of the reovirus λ2-encoding L2 gene from strains T1L (NC_004259), type 2 Jones (T2J) (NC_004260), T3D (NC_004275), T1Neth85 (AF378004), T2SV59 (AF378006), T3C9 (AF378007), T3C18 (AF378008), T3C87 (AF378009), and T3C93 (AF378010) were aligned using the protein sequence alignment algorithm in MacVector, version 8.0.1 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA).

Plasmid constructs.

Human JAM-A was subcloned into expression plasmid pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen) (34). Truncation mutant JAM-A-ΔCT was generated by PCR using full-length JAM-A cDNA as the template. Amino acids 1 to 260 (Δ261-299) were cloned and appended with a stop codon using T7 primer and 5′-TACGGGATCCTCAGGCAAACCAGATGCC-3′ as the forward and reverse primers, respectively. The gene-specific primer encompasses nucleotides 981 to 995 of the JAM-A cDNA. The PCR product was digested with BamHI (recognition site underlined in the reverse primer sequence) and subcloned into the complementary restriction sites of pcDNA3.1+. Fidelity of cloning was confirmed by automated sequencing. Plasmid constructs encoding murine integrin αv (33) and α2 (30) were previously described. A cDNA encoding murine β1 integrin cloned into the EcoRI site of pGEM1 was obtained from Richard Hynes (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) (D. W. DeSimone, V. Patel, and R. O. Hynes, unpublished). Integrin cDNAs were subcloned into the expression plasmid pcDNA3.1+.

Transient transfection of CHOs and CEFs.

Monolayers of cells in a 24-well plate (Costar, Cambridge, MA) were transfected with empty vector or plasmids encoding receptor constructs by using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated for 24 h to allow receptor expression prior to adsorption with either reovirus virions or ISVPs for infectivity studies.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Surface expression of integrin subunits on HeLa cells was determined by flow cytometry. Cells were detached from plates by using PBS-EDTA (20 mM EDTA). Cells were washed and centrifuged at 2,000 × g to form a pellet, resuspended with integrin-specific or control antibodies in PBS- bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich) (5% BSA), and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Cells were washed twice and incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to R-phycoerythrin (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) at 4°C for 1 h. Cells were washed, resuspended in PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results were analyzed using the Windows Multiple Document 2.8 flow cytometry application (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA).

The mean fluorescence intensity was measured for an average of 14,000 gated events for cells treated with control or integrin-specific antibodies. Events were gated relative to cells stained with an appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to phycoerythrin. Reovirus binding to GD25 and GD25β1A cells was analyzed by adsorbing cells with 2 × 1011 FITC-labeled particles of strain T1L at 4°C for 1 h. Cells were washed and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Fluorescent focus assay of viral infection.

Cells were plated in 24-well or 96-well plates (Costar) and adsorbed with virus at various multiplicities of infection (MOIs) at either 4°C or room temperature for 30 to 60 min. Inocula were removed, cells were washed, and complete medium was added. Infected cells were incubated at 37°C for 16 to 24 h to allow a single cycle of viral replication. Cells were fixed with methanol at −20°C for at least 30 min. Fixed cells were incubated with PBS-BSA (5% BSA) for at least 15 min, followed by incubation with reovirus-specific polyclonal antiserum (1:500) in PBS-Triton X-100 (0.5% Triton X-100) at room temperature for 1 h. Cells were washed twice and incubated with an Alexa 488- or 546-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000) in PBS-Triton X-100 (0.5% Triton X-100) at room temperature for 1 h.

Cells were washed twice and visualized by indirect immunofluorescence at a magnification of 20× using an Axiovert 200 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, New York, NY). Infected cells (fluorescent focus units [FFU]) were identified by diffuse cytoplasmic fluorescence staining that was excluded from the nucleus. Reovirus-infected cells were quantified by counting random fields of view of equivalently confluent monolayers for three to five fields of view for triplicate wells or by counting the entire well for triplicate wells (4).

Confocal imaging of reovirus internalization.

GD25 and GD25β1A cells were plated on coverslips in 24-well plates. Cells were chilled at 4°C for 45 min prior to infection, washed with PBS, adsorbed with 8 × 105 particles per cell of T1L virions in gelatin saline, and returned to 4°C for 1 h. The MOI used was the minimum number of particles required to detect signal by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy at early time points postinfection. Cells were either washed and fixed or nonadherent reovirus was aspirated and replaced with warm Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and returned to 37°C. At 10-min intervals, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min. Excess formaldehyde was quenched with an equal amount of 0.1 M glycine, followed by washing with PBS. Cells were treated with 1% Triton X-100 for 5 min and incubated with PBS-BGT (PBS, 0.5% BSA, 0.1% glycine, and 0.05% Tween 20) for 10 min. Cells were incubated with reovirus-specific polyclonal antiserum (1:500) in PBS-BGT for 1 h and washed with PBS-BGT. Cells were stained with donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) (1:500) to visualize reovirus, phalloidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 546 (Molecular Probes) (1:100) to visualize actin, and TO-PRO 3 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 642 (Molecular Probes) (1:1,000) to visualize DNA. Cells were incubated for 1 h with secondary antibodies and fluorescent probes in PBS-BGT and washed with PBS-BGT. Coverslips were removed from wells and placed on slides using Prolong Anti-Fade mounting medium (Molecular Probes). Images were captured on a Zeiss LSM 510 laser-scanning confocal microscope using LSM 510 software.

Virus internalization was quantified by enumerating fluorescent particles localized at the cell periphery and particles internalized into the cytoplasm to determine the total number of fluorescent particles per cell. Ten cells were analyzed for each time point. The number of internalized particles was measured as a percentage of the total number of particles per cell.

Statistical analysis.

Means of triplicate samples were compared by using an unpaired Students' t test (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The JAM-A cytoplasmic tail is dispensable for reovirus infection.

JAM-A is a serotype-independent reovirus receptor with a cytoplasmic tail known to interact with a variety of proteins (6, 28, 29). To determine whether the JAM-A cytoplasmic tail is required for reovirus entry, we generated a JAM-A cytoplasmic tail deletion mutant (JAM-A-ΔCT) and tested its capacity to support reovirus infection following transfection of CHO cells. CHO cells do not express detectable levels of JAM-A (55, 60) and are poorly permissive for reovirus infection (34). Cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding full-length JAM-A, JAM-A-ΔCT, or empty vector as a control. Equivalent cell surface expression of transfected constructs was confirmed by flow cytometry (data not shown).

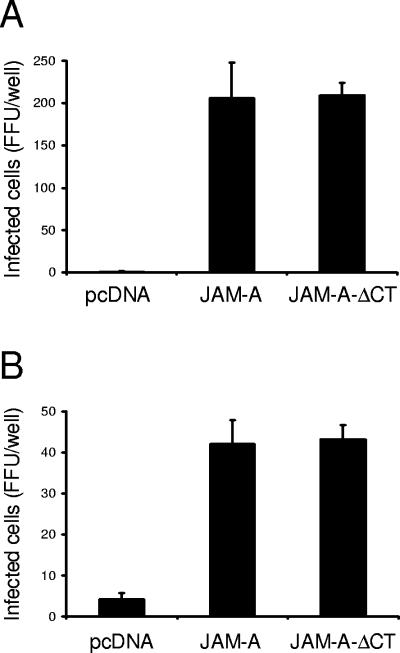

The capacity of reovirus to infect CHO cells following transfection with the JAM-A constructs was tested using reovirus fluorescent focus assays. Following transient transfection of CHO cells with empty vector, JAM-A, or JAM-A-ΔCT, cells were adsorbed with reovirus strains T1L and T3D and scored for infection by indirect immunofluorescence at 20 h postinfection (Fig. 1). Expression of either full-length or truncated JAM-A was sufficient to allow reovirus infection of CHO cells, permitting viral protein production of both type 1 and type 3 reovirus strains. These results indicate that the JAM-A cytoplasmic tail is not required for efficient reovirus attachment and infection.

FIG. 1.

JAM-A cytoplasmic tail is not required for reovirus infection. CHO cells were transiently transfected with empty vector or plasmids encoding JAM-A or JAM-A-ΔCT. Following incubation for 24 h to permit receptor expression, cells were adsorbed with reovirus strains T1L (A) or T3D (B) at an MOI of 0.1 FFU per cell at room temperature for 1 h. Cells were washed with PBS, incubated in complete medium at 37°C for 20 h, and stained by indirect immunofluorescence. Infected cells were quantified by counting cells exhibiting cytoplasmic staining in entire wells for triplicate experiments. The results are expressed as the mean FFU per well for triplicate samples. Error bars indicate standard deviations. CHO cells support a low level of infection by type 3 reovirus in the absence of JAM-A, likely attributable to the expression of sialic acid (16, 34).

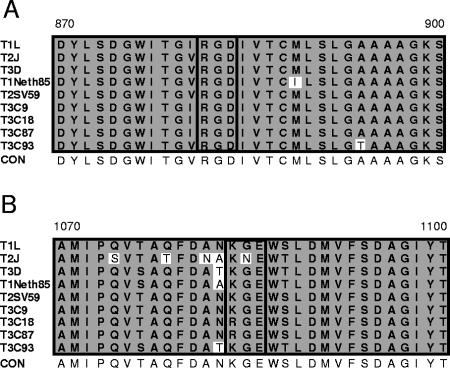

Reovirus outer capsid proteins contain integrin-binding sequences. Structural and functional analyses indicate that reovirus and adenovirus share remarkably similar mechanisms of attachment (70, 71). To determine whether reovirus outer capsid proteins contain sequences that could potentially engage integrins, we performed a search for integrin-binding motifs in the σ1, σ3, μ1, and λ2 proteins, which form the reovirus outer capsid (26). We identified two common integrin-binding motifs, RGD and KGE, in the deduced amino acid sequence of the λ2 protein (Fig. 2). The RGD motif is conserved in all reovirus strains for which sequence information is available (15, 67); the KGE motif is conserved in all of those strains except T2J (15, 67). The λ2 protein is a component of the reovirus outer capsid and core (26). It is structurally arranged as a pentamer at the virion fivefold axes of symmetry and forms the base for attachment protein σ1 (26, 63). The presence of conserved integrin-binding motifs in the reovirus λ2 protein led us to test whether reovirus utilizes integrins to mediate internalization.

FIG. 2.

Reovirus outer capsid protein λ2 contains integrin-binding sequences. Alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of the reovirus λ2 protein for the indicated strains. Amino acid residues are designated by the single-letter code. Amino acid positions are indicated above the first and last letters. Integrin-binding RGD (A) and KGE (B) motifs are highlighted by a black box. Nonconserved sequences are shown in unshaded boxes. CON, consensus sequence.

An antibody specific for β1 integrin inhibits reovirus infection of HeLa cells.

To determine whether integrins are required for reovirus infection, we first used flow cytometry to analyze integrin expression on the surface of HeLa cells. HeLa cells were incubated with integrin-specific MAbs and a phycoerythrin-labeled secondary antibody (Table 1). RGD-binding integrin subunits α3, α5, αv, and β1 and KGE-binding integrin subunits α1, α2, α6, and β1 (43) were detected on HeLa cells at levels above those in control antibody-treated cells. RGD-binding integrin heterodimer αvβ5 also was detected at levels above that of the control, while there was low-level expression of αvβ3. Thus, HeLa cells express both RGD- and KGE-binding integrins.

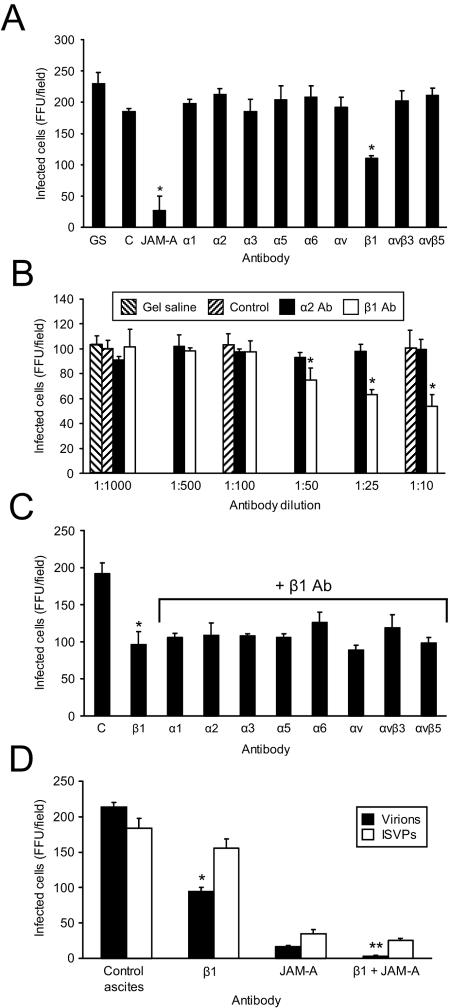

To assess a role for integrins in reovirus replication, we tested antibodies specific for the RGD- and KGE-binding integrins expressed on HeLa cells for the capacity to block reovirus infection. HeLa cells were incubated with integrin-specific and control antibodies prior to adsorption with reovirus virions. Viral infection was detected by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 3A). We found that β1-specific MAb DE9 resulted in a 50% reduction in infection (P < 0.05), while antibodies specific for the other integrin subunits expressed on HeLa cells had no effect. Control antibodies produced anticipated effects; JAM-A-specific MAb J10.4 inhibited infection, whereas ICAM-specific MAb (data not shown) or control mouse ascites (Fig. 3A) did not. The effect of MAb DE9 was dose dependent (Fig. 3B), providing further evidence that the inhibition of infection was dependent on integrin blockade.

FIG. 3.

β1 integrin antibody reduces reovirus infection of HeLa cells. HeLa cells were treated with gel saline (GS), control ascites (C), JAM-A-specific MAb J10.4, or antibodies specific for the α and β integrins shown (20 μg per ml or as diluted ascites) (A), gel saline, control ascites (Control), α2-specific MAb AA10, or β1-specific MAb DE9 (at the indicated dilutions) (B), antibodies specific for the α and β integrins shown in the presence of β1-specific MAb DE9 (1:10) (C), control ascites, β1-specific MAb DE9, JAM-A-specific MAb J10.4, or JAM-A-specific MAb J10.4 in combination with β1-specific MAb DE9 (D), and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Antibody-treated cells were infected with virions or ISVPs of T1L at an MOI of 0.1 FFU per cell at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS, incubated in complete medium at 37°C for 16 h, and stained by indirect immunofluorescence. Infected cells were quantified by counting cells exhibiting cytoplasmic staining in three fields of view for triplicate samples. The results are expressed as the mean FFU per field for triplicate experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 in comparison to the control; **, P < 0.05 in comparison to HeLa cells treated with JAM-A-specific MAb J10.4 alone.

To determine whether particular α subunits pair with β1 integrin to facilitate reovirus infection, we tested whether treatment with α integrin-specific antibodies was capable of enhancing the inhibitory effect of β1 integrin-specific MAb DE9 on reovirus infection. We also tested whether antibodies specific for other β integrin subunits expressed on HeLa cells, β3 and β5, were capable of infection blockade. HeLa cells were treated with MAb DE9 in combination with other integrin-specific antibodies prior to adsorption with reovirus virions (Fig. 3C). While treatment of HeLa cells with MAb DE9 resulted in a 50% reduction in reovirus infection, none of the other integrin-specific antibodies tested reduced reovirus infection to a greater extent than that resulting from treatment with DE9 alone. These results suggest that the integrin epitope bound by reovirus is blocked by β1-specific MAb DE9 and not by the other MAbs used in these experiments.

JAM-A MAb J10.4 blocks reovirus infection ∼90% (Fig. 3A). To determine whether the residual level of infection in the presence of MAb J10.4 was dependent on reovirus interactions with β1 integrin, we treated HeLa cells with JAM-A-specific MAb J10.4 in combination with MAb DE9 prior to adsorption with reovirus virions (Fig. 3D). Treatment of HeLa cells with MAb J10.4 and MAb DE9 completely abrogated reovirus infection, indicating that the effect of JAM-A blockade is enhanced when β1 integrin is not available for interactions with reovirus. Treatment with MAb DE9 did not significantly inhibit infection by ISVPs (Fig. 3D), suggesting that viral attachment is not affected by β1 integrin blockade. Taken together, these results support the conclusion that a β1-specific antibody blocks reovirus infection at a step subsequent to attachment but prior to uncoating, implicating β1 integrin in reovirus internalization.

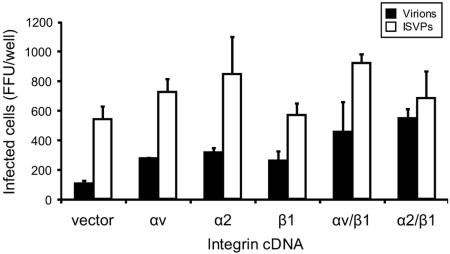

Transient transfection of integrin cDNAs allows reovirus infection of JAM-A-expressing CEFs.

Ectopic expression of JAM-A in CEFs rescues infection by reovirus ISVPs but not by virions (5), suggesting that these cells exhibit a cell-specific block at the entry or uncoating phases of reovirus infection. To test the capacity of integrins to confer infection of CEFs by reovirus virions, CEFs were transiently transfected with a JAM-A-encoding plasmid in the presence or absence of murine αv, α2, or β1 integrin-encoding plasmids singly or in αβ pairs. Transfected cells were infected with reovirus virions or ISVPs, and infection was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 4). Expression of β1 integrin paired with either of the murine α integrin subunits provided an approximately fourfold enhancement of infection by reovirus virions in comparison to that in cells transfected with JAM-A alone. These data suggest that β1 integrin expression complements a reovirus cell entry defect in CEFs and provide further support for the involvement of β1 integrin in reovirus internalization.

FIG. 4.

β1 integrin expression enhances reovirus infection of CEFs. CEFs were transiently transfected with JAM-A-encoding plasmid alone (vector) or in combination with plasmids encoding the integrin subunits shown. Following 24 h to allow receptor expression, transfected cells were adsorbed with T1L virions or ISVPs at an MOI of 1 FFU per cell at room temperature for 1 h. Cells were washed with PBS, incubated in complete medium at 37°C for 20 h, and stained by indirect immunofluorescence. Infected cells were quantified by counting cells exhibiting cytoplasmic staining in entire wells for duplicate samples. The results are expressed as the mean FFU per well for duplicate experiments. Error bars indicate the range of data. Shown is a representative experiment of three independent experiments performed.

Cells deficient in β1 integrin have a decreased capacity to support reovirus infection.

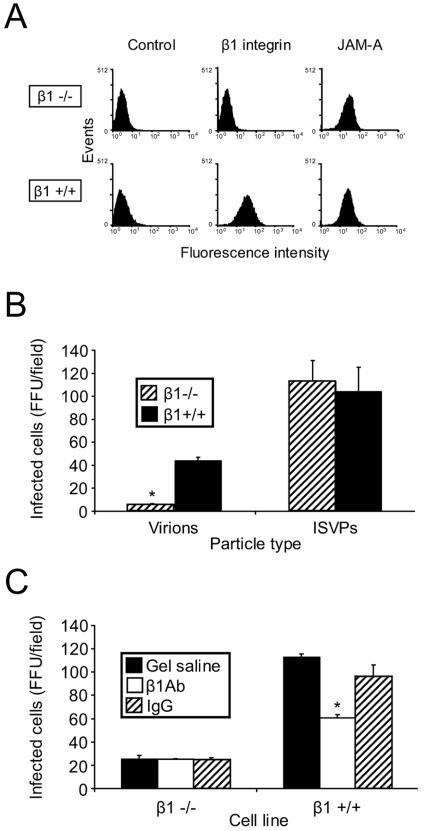

To further assess a role for β1 integrin in reovirus infection, we tested the capacity of reovirus to infect cells deficient in the β1-integrin subunit. GD25 cells are murine embryonic stem cells derived from β1-null embryos (78). GD25β1A cells are GD25 cells that have been engineered to stably express β1 integrin and thus serve as an isogenic control for GD25 cells. Flow cytometric analysis confirmed that while both cells express JAM-A, only GD25β1A cells express β1 integrin (Fig. 5A). GD25 cells (β1−/−) and GD25β1A cells (β1+/+) (78) were adsorbed with reovirus virions or ISVPs, and infection was scored by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 5B). In comparison to β1+/+ cells, β1−/− cells were substantially less susceptible to infection by virions, while infection by ISVPs was equivalent in both cell types. Importantly, preincubation of β1+/+ cells with murine β1 integrin-specific MAb CD29 reduced infection in β1+/+ cells (Fig. 5C), indicating that enhancement of infection is due to expression of β1 integrin. Therefore, β1 integrin is required for efficient reovirus infection.

FIG. 5.

Cells deficient in β1 integrin are less permissive for reovirus infection. (A) GD25 (β1−/−) and GD25β1A (β1+/+) cells were detached from plates with 20 mM EDTA, washed, and incubated with antibodies specific for either murine β1 integrin or murine JAM-A. Cell surface expression of these molecules was detected by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as fluorescence intensity. GD25 and GD25β1A cells were untreated (B) or pretreated with β1-specific MAb CD29 (β1 Ab) or a hamster isotype-matched control MAb (IgG) at room temperature for 1 h (C), adsorbed with virions or ISVPs of T1L at an MOI of 0.1 FFU per cell, and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS, incubated in complete medium at 37°C for 20 h, and stained by indirect immunofluorescence. Infected cells were quantified by counting cells exhibiting cytoplasmic staining in five fields of view for duplicate samples. The results are expressed as the mean FFU per field for triplicate experiments. *, P < 0.05 in comparison to the control.

Reovirus binding to β1−/− and β1+/+ cells is equivalent.

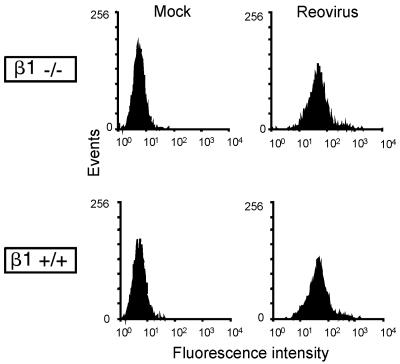

Equivalent infection of β1−/− and β1+/+ cells by ISVPs (Fig. 5B) suggests that reovirus is capable of efficiently binding to both cell types. To directly test this hypothesis, β1−/− and β1+/+ cells were mock treated or incubated with FITC-labeled virions and binding was assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 6). In these experiments, we found that reovirus binds equivalently to β1−/− and β1+/+ cells. These data demonstrate a function for β1 integrin in reovirus infection at a step subsequent to viral attachment.

FIG. 6.

Reovirus exhibits equivalent binding to β1−/− and β1+/+ cells. GD25 (β1−/−) and GD25β1A (β1+/+) cells were incubated with either PBS (mock) or 2 × 1011 FITC-labeled T1L virions at 4°C for 1 h and analyzed by flow cytometry to assess reovirus binding to the cell surface. The results are expressed as fluorescence intensity.

β1 integrin enhances the efficiency of reovirus internalization.

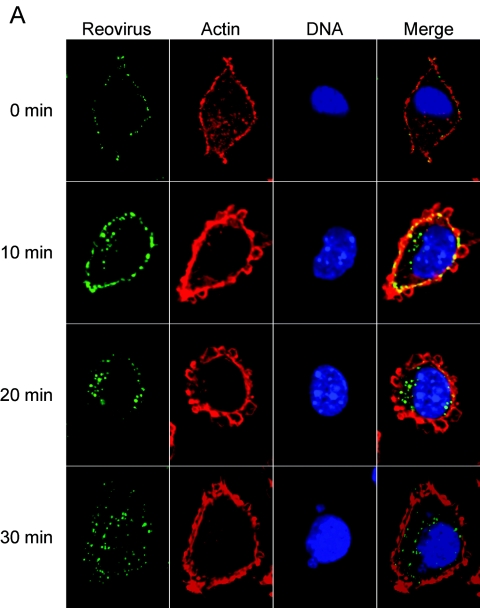

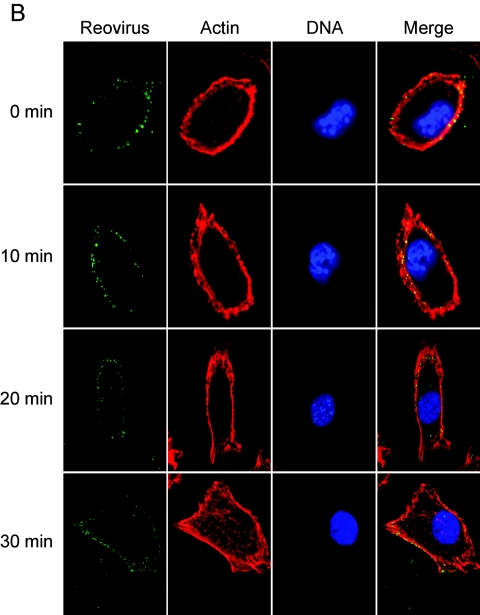

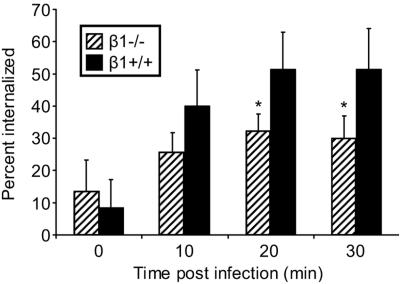

To directly assess the role of β1 integrin in reovirus internalization, β1−/− and β1+/+ cells were infected at 4°C and then warmed to 37°C over a time course concurrent with reovirus entry (2, 72). At 10-min intervals, cells were fixed, stained for indirect immunofluorescence, and examined by confocal microscopy. Representative confocal micrographic images of reovirus-infected β1−/− and β1+/+ cells are shown in Fig. 7. Immediately after viral adsorption, both cell types exhibited reovirus staining at the cell periphery. At 10 min postadsorption, some reovirus staining was observed at the cell periphery, yet intracellular staining in β1+/+ cells was also observed. At 20 and 30 min postadsorption, the majority of virions had entered the β1+/+ cells and had a perinuclear location. In sharp contrast to the findings made using β1+/+ cells, viral entry was markedly delayed in β1−/− cells, with the majority of reovirus virions remaining at the cell periphery throughout the time course. At later time points (30 min postadsorption), some virions were present within the cytoplasm, but these were the minority. These findings suggest that expression of β1 integrin enhances reovirus entry.

FIG.7.

β1 integrin enhances reovirus entry into cells. (A) GD25β1A (β1+/+) and (B) GD25 (β1−/−) cells were chilled, adsorbed with T1L virions, and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Nonadherent virus was removed, warm medium was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C for the times shown. Cells were fixed, stained for reovirus (green), actin (red), and DNA (blue), and imaged using confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Representative digital fluorescence images of the same field are shown in each row.

To quantify reovirus internalization into β1−/− and β1+/+ cells, we determined the number of internalized fluorescent particles as a percentage of the total number of fluorescent particles per cell at various times postadsorption (Fig. 8). At 0 and 10 min postadsorption, the percentage of particles internalized into β1−/− and β1+/+ cells was equivalent, ∼10 and ∼30%, respectively. However, at 20 and 30 min postadsorption, the percentage of reovirus particles internalized into β1+/+ cells was ∼50%, while the percentage of particles internalized into β1−/− cells was only ∼30% (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8). These data indicate that β1 integrin enhances reovirus entry at early times postadsorption, suggesting a direct role for β1 integrin as a reovirus internalization receptor.

FIG. 8.

Quantification of reovirus internalization into β1−/− and β1+/+ cells. Viral internalization was quantitated by enumerating fluorescent particles localized at the cell periphery and particles internalized into the cytoplasm to determine the total number of fluorescent particles per cell. The results are expressed as mean percent internalization (internalized fluorescent particles/total number of fluorescent particles per cell) for 10 cells for each time point. *, P < 0.05 in comparison to β1+/+ cells.

DISCUSSION

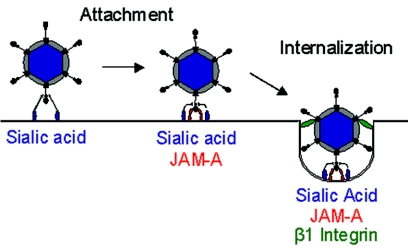

In this study, we performed experiments to define the molecular determinants of reovirus internalization. We show that antibodies specific for β1 integrin inhibit reovirus infection at a postattachment step. We provide evidence that expression of β1 integrin promotes infection by reovirus virions in cells with a block to viral internalization and that viral entry is substantially diminished in cells deficient in β1 integrin expression. Together, these data provide strong evidence that β1 integrin serves as a coreceptor to mediate reovirus internalization. These findings suggest a new model for attachment and cell entry of reovirus (Fig. 9). In this model, we propose that reovirus initially interacts with cells via low-affinity binding to carbohydrate. These interactions are followed by high-affinity engagement of JAM-A, which positions the virus on the cell surface for subsequent interactions with β1 integrin to trigger viral endocytosis.

FIG. 9.

Receptors for reovirus attachment and cell entry. Reovirus initially engages cells by low-affinity interactions with carbohydrate. For type 3 reovirus strains, this carbohydrate is sialic acid. Reovirus-carbohydrate interactions are followed by high-affinity binding to JAM-A, which positions the virus on the cell surface for subsequent interactions with β1 integrin to trigger viral endocytosis.

Integrins have been identified as attachment and entry receptors for several viruses, including echovirus (α2β1) (8), foot-and-mouth disease virus (αvβ1, αvβ3, and αvβ6) (9, 44, 45), hantaviruses NY-1 and Sin Nombre virus (β3 integrins) (37), Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (α3β1) (1), and cytomegalovirus (α2β1, α6β1, and αvβ3) (32). The Reoviridae family member rotavirus also engages a variety of integrins for attachment and cell entry. Rotavirus strains RRV, SA11, and Wa bind to the I (inserted) domain of α2β1 integrin via an Asp-Gly-Glu integrin-binding motif in the VP4 spike protein to effect viral attachment (39). The interactions of rotavirus outer capsid protein VP7 with integrins αxβ2 and αvβ3 can mediate viral entry (39, 82). Integrin α4β1 also can serve as a receptor for rotavirus strain SA11, which contains α4β1 integrin-binding sequences Leu-Asp-Val in VP7 and Ile-Asp-Ala in VP4 (41). Interestingly, like reovirus, adenovirus engages a specific cell surface protein, CAR, prior to interactions with integrins, which function subsequent to viral attachment to mediate viral endocytosis (50, 80). Therefore, the identification of β1 integrin as a reovirus internalization receptor suggests that the conservation of attachment strategies used by reovirus and adenovirus (70, 71) extends to mechanisms of internalization.

Although the specific reovirus protein required for integrin binding is not apparent from our studies, the λ2 protein is a promising candidate. The λ2 protein forms a pentameric turret at the virion fivefold symmetry axes and serves as the insertion site for trimers of attachment protein σ1 (26). Thus, λ2 is the reovirus analogue of the adenovirus penton base protein, which mediates the engagement of integrins by adenovirus (22, 80). Interestingly, λ2 also contains conserved RGD and KGE motifs (15), the preferred interaction motifs for several β1 integrin heterodimers (43).

Structural information for λ2 is available in the context of the reovirus core but not for the intact virion. In the core, the KGE motif is exposed on the top of the λ2 turret, where it would be accessible to a receptor. The RGD motif is also surface exposed, but it appears to be less accessible. However, the λ2 structure in the core may not be identical to that in the virion, as the protein undergoes major conformational changes during virion-to-core disassembly (26). Therefore, it is possible that both the RGD and KGE motifs are accessible to interactions with β1 integrin during engagement of the cell surface by the virus.

A human β1 integrin-specific antibody (DE9) reduced reovirus infection of HeLa cells by 50% (Fig. 3). Similarly, a murine β1 integrin-specific antibody (CD29) blocked infection of β1-expressing mouse embryonic stem cells by ∼50% (Fig. 4). Interestingly, MAb DE9 also blocks infection of echovirus (8) and cytomegalovirus (32), suggesting that an epitope in β1 integrin recognized by MAb DE9 may be a preferred binding site for multiple viruses. It is possible that the residual level of reovirus infection following β1 integrin antibody treatment is attributable to other internalization receptors on the cell surface that may be integrin or nonintegrin molecules. However, it is noteworthy that treatment of HeLa cells with both MAb DE9 and JAM-A-specific MAb J10.4 completely abolishes reovirus growth (Fig. 3D). This finding suggests that the residual infection in J10.4-treated HeLa cells is due to reovirus interactions with β1 integrin. Thus, it appears that blockade of reovirus infection by integrin-specific antibodies is inefficient because complete inhibition of virus-integrin interactions is not possible if the virus is tightly adhered to the cell surface by JAM-A.

Since antibodies specific for β3 and β5 integrins did not inhibit reovirus infection, it is likely that only β1 integrin can serve a reovirus internalization function. Antibodies specific for the α integrin subunits expressed on HeLa cells did not further reduce reovirus infection following treatment with a β1 integrin-specific antibody (Fig. 3C). We envision three possible explanations for this result. First, reovirus may directly engage a ligand-binding domain of β1 integrin. Second, reovirus may utilize β1 integrin when paired with numerous α subunits that have redundant functions. However, treatment of HeLa cells with a β1 integrin-specific antibody and a mixture of antibodies specific for α1, α2, α3, α5, α6, and αv integrins did not diminish reovirus infection in comparison to cells treated with a β1 integrin-specific antibody alone (data not shown). Third, reovirus may engage an epitope of an integrin α subunit that is not recognized by the antibodies used in our experiments. Further studies are required to define the biophysical basis of reovirus-integrin interactions.

JAM-A is required for high-affinity reovirus attachment to numerous cell types (5, 16, 34, 56). However, the JAM-A cytoplasmic tail is not necessary for viral endocytosis (Fig. 1). JAM-A likely tethers the virus to the cell surface to facilitate secondary interactions with β1 integrin (Fig. 9). This model is analogous to the mechanism of lymphocyte homing, in which adhesion molecules such as JAM-A provide initial cellular contacts to facilitate subsequent interactions with integrins for diapedesis or signaling (65). An interesting possibility is that JAM-A may be associated with β1 integrin on the host cell plasma membrane. If such were the case, initial JAM-A engagement might facilitate integrin binding, clustering, and viral endocytosis. In support of this hypothesis, JAM-A has been shown to regulate β1 integrin expression and localization (54).

The cytoplasmic domains of integrin subunits are involved in a number of signaling pathways (42). The β1 integrin cytoplasmic domain is linked to cytoskeletal proteins, including talin (62) and α-actinin (59), and signaling molecules, including paxillin and focal adhesion kinase (66). In addition, the β1 integrin cytoplasmic domain contains two Asn-Pro-any residue-Tyr (NPXY) motifs (64), which are common sequence motifs in the cytoplasmic domains of many receptors and serve as recognition sites for the cellular endocytic machinery (21, 24). NPXY motifs interact with the μ2 subunit of the adaptor protein 2 complex (12, 61), which can recruit clathrin and trigger clathrin-mediated endocytosis (47).

Since clathrin-dependent mechanisms have been implicated in reovirus cell entry (31), it seems plausible that reovirus engagement of β1 integrin leads to clathrin-mediated endocytosis through signaling regulated by the β1 integrin cytoplasmic domain. It is noteworthy that Kaposi's sarcoma-related herpesvirus binding to α3β1 integrin (1) and cytomegalovirus binding to β1 integrin (32) activate focal adhesion kinase. In addition, adenovirus engagement of αv integrins induces activation of phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase, which is required for adenovirus endocytosis (51).

Identification of β1 integrin as a receptor that triggers reovirus entry raises the possibility that coreceptor binding influences reovirus tropism and disease. Reovirus serotypes differ in mechanisms of spread, tropism for cells in the central nervous system, and disease outcome in the infected host (73). Previous studies using reassortant genetics and comparative sequence analysis demonstrated that these phenotypes segregate most strongly with viral attachment protein σ1, suggesting that reovirus serotypes bind to different receptors (74, 76, 77). However, the σ1-encoding S1 gene is not the sole determinant of reovirus growth at some sites within the host. For example, the λ2-encoding L2 gene influences viral growth in the intestine (11) and spread to new hosts (46). Moreover, JAM-A functions as a receptor for all three reovirus serotypes (16); therefore, JAM-A cannot explain serotype-dependent differences in reovirus pathogenesis. The presence or absence of particular integrins at distinct physiologic sites may critically influence the course of reovirus infection. In support of a role for coreceptor utilization in reovirus growth, reovirus infection can occur in the absence of σ1 (19) or JAM-A (5), albeit at greatly reduced efficiency. These findings highlight the complex nature of reovirus attachment and entry and suggest that reovirus tropism and pathogenesis are not dictated by primary receptor interactions alone. It is possible that tropism and pathogenesis are determined by the concerted action of attachment and internalization receptors, perhaps not all of which have been discovered.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roy Zent for helpful discussions, members of our laboratory for review of the manuscript, Kathy Allen and the Nashville Veterans Affairs Hospital Flow Cytometry Facility for assistance with flow cytometry, the Vanderbilt Imaging Core for help with confocal microscopy, and Aaron Derdowski for assistance with the confocal image analysis. We thank Xuemin Chen and Paul Spearman for providing CEFs, Richard Hynes for providing murine integrin cDNA constructs, Deane Mosher for providing GD25 and GD25β1A cells, Charles Parkos for providing hJAM-A-specific MAb J10.4 and control ascites, Beat Imof for providing mJAM-A-specific MAb H202-106-7-4, Richard Bankert for providing α2-specific MAb 6F1, and John Williams for providing antibodies.

This research was supported by Public Health Service awards AI007281 (M.S.M.), CA09385 (J.C.F.), AI07474 (S.A.K.-B.), and AI32539, the Vanderbilt University Research Council (J.C.F.), and the Elizabeth B. Lamb Center for Pediatric Research. Additional support was provided by Public Health Service awards CA68485 for the Vanderbilt Cancer Center and DK20593 for the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akula, S. M., N. P. Pramod, F. Z. Wang, and B. Chandran. 2002. Integrin α3b1 (CD 49c/29) is a cellular receptor for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) entry into the target cells. Cell 108:407-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baer, G. S., and T. S. Dermody. 1997. Mutations in reovirus outer capsid protein σ3 selected during persistent infections of L cells confer resistance to protease inhibitor E64. J. Virol. 71:4921-4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baer, G. S., D. H. Ebert, C. J. Chung, A. H. Erickson, and T. S. Dermody. 1999. Mutant cells selected during persistent reovirus infection do not express mature cathepsin L and do not support reovirus disassembly. J. Virol. 73:9532-9543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton, E. S., J. L. Connolly, J. C. Forrest, J. D. Chappell, and T. S. Dermody. 2001. Utilization of sialic acid as a coreceptor enhances reovirus attachment by multistep adhesion strengthening. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2200-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton, E. S., J. C. Forrest, J. L. Connolly, J. D. Chappell, Y. Liu, F. Schnell, A. Nusrat, C. A. Parkos, and T. S. Dermody. 2001. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell 104:441-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bazzoni, G., O. M. Martinez-Estrada, F. Orsenigo, M. Cordenonsi, S. Citi, and E. Dejana. 2000. Interaction of junctional adhesion molecule with the tight junction components ZO-1, cingulin, and occludin. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20520-20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergelson, J. M., J. A. Cunningham, G. Droguett, E. A. Kurt-Jones, A. Krithivas, J. S. Hong, M. S. Horwitz, R. L. Crowell, and R. W. Finberg. 1997. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 275:1320-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergelson, J. M., M. P. Shepley, B. M. Chan, M. E. Hemler, and R. W. Finberg. 1992. Identification of the integrin VLA-2 as a receptor for echovirus 1. Science 255:1718-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berinstein, A., M. Roivainen, T. Hovi, P. W. Mason, and B. Baxt. 1995. Antibodies to the vitronectin receptor (Integrin αvβ3) inhibit binding and infection of foot-and-mouth disease virus to cultured cells. J. Virol. 69:2664-2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bewley, M. C., K. Springer, Y. B. Zhang, P. Freimuth, and J. M. Flanagan. 1999. Structural analysis of the mechanism of adenovirus binding to its human cellular receptor, CAR. Science 286:1579-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodkin, D. K., and B. N. Fields. 1989. Growth and survival of reovirus in intestinal tissue: role of the L2 and S1 genes. J. Virol. 63:1188-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boll, W., I. Rapoport, C. Brunner, Y. Modis, S. Prehn, and T. Kirchhausen. 2002. The μ2 subunit of the clathrin adaptor AP-2 binds to FDNPVY and YppØ sorting signals at distinct sites. Traffic 3:590-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borsa, J., B. D. Morash, M. D. Sargent, T. P. Copps, P. A. Lievaart, and J. G. Szekely. 1979. Two modes of entry of reovirus particles into L. cells. J. Gen. Virol. 45:161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borsa, J., M. D. Sargent, P. A. Lievaart, and T. P. Copps. 1981. Reovirus: evidence for a second step in the intracellular uncoating and transcriptase activation process. Virology 111:191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breun, L. A., T. J. Broering, A. M. McCutcheon, S. J. Harrison, C. L. Luongo, and M. L. Nibert. 2001. Mammalian reovirus L2 gene and λ2 core spike protein sequences and whole-genome comparisons of reoviruses type 1 Lang, type 2 Jones, and type 3 Dearing. Virology 287:333-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell, J. A., P. Shelling, J. D. Wetzel, E. M. Johnson, G. A. R. Wilson, J. C. Forrest, M. Aurrand-Lions, B. Imhof, T. Stehle, and T. S. Dermody. 2005. Junctional adhesion molecule-A serves as a receptor for prototype and field-isolate strains of mammalian reovirus. J. Virol. 79:7967-7978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandran, K., D. L. Farsetta, and M. L. Nibert. 2002. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein m1 mediates membrane disruption. J. Virol. 76:9920-9933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandran, K., J. S. Parker, M. Ehrlich, T. Kirchhausen, and M. L. Nibert. 2003. The delta region of outer-capsid protein μ1 undergoes conformational change and release from reovirus particles during cell entry. J. Virol. 77:13361-13375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandran, K., S. B. Walker, Y. Chen, C. M. Contreras, L. A. Schiff, T. S. Baker, and M. L. Nibert. 1999. In vitro recoating of reovirus cores with baculovirus-expressed outer-capsid proteins μ1 and σ3. J. Virol. 73:3941-3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chappell, J. D., A. Prota, T. S. Dermody, and T. Stehle. 2002. Crystal structure of reovirus attachment protein σ1 reveals evolutionary relationship to adenovirus fiber. EMBO J. 21:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, W. J., J. L. Goldstein, and M. S. Brown. 1990. NPXY, a sequence often found in cytoplasmic tails, is required for coated pit-mediated internalization of the low density lipoprotein receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 265:3116-3123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu, C. Y., P. Mathias, G. R. Nemerow, and P. L. Stewart. 1999. Structure of adenovirus complexed with its internalization receptor, αvβ5 integrin. J. Virol. 73:6759-6768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen, C. J., J. T. Shieh, R. J. Pickles, T. Okegawa, J. T. Hsieh, and J. M. Bergelson. 2001. The coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor is a transmembrane component of the tight junction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:15191-15196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis, C. G., M. A. Lehrman, D. W. Russell, R. G. Anderson, M. S. Brown, and J. L. Goldstein. 1986. The J.D. mutation in familial hypercholesterolemia: amino acid substitution in cytoplasmic domain impedes internalization of LDL receptors. Cell 45:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dermody, T. S., and K. L. Tyler. 2005. Introduction to viruses and viral diseases, p. 1729-1742. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 6th ed. Churchill Livingstone, New York, N.Y.

- 26.Dryden, K. A., G. Wang, M. Yeager, M. L. Nibert, K. M. Coombs, D. B. Furlong, B. N. Fields, and T. S. Baker. 1993. Early steps in reovirus infection are associated with dramatic changes in supramolecular structure and protein conformation: analysis of virions and subviral particles by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction. J. Cell Biol. 122:1023-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebert, D. H., J. Deussing, C. Peters, and T. S. Dermody. 2002. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:24609-24617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebnet, K., C. U. Schulz, M. K. Meyer Zu Brickwedde, G. G. Pendl, and D. Vestweber. 2000. Junctional adhesion molecule interacts with the PDZ domain-containing proteins AF-6 and ZO-1. J. Biol. Chem. 275:27979-27988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebnet, K., A. Suzuki, Y. Horikoshi, T. Hirose, M. K. Meyer Zu Brickwedde, S. Ohno, and D. Vestweber. 2001. The cell polarity protein ASIP/PAR-3 directly associates with junctional adhesion molecule (JAM). EMBO J. 20:3738-3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edelman, J. M., B. M. Chan, S. Uniyal, H. Onodera, D. Z. Wang, N. F. St John, L. Damjanovich, D. B. Latzer, R. W. Finberg, and J. M. Bergelson. 1994. The mouse VLA-2 homologue supports collagen and laminin adhesion but not virus binding. Cell Adhes. Commun. 2:131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehrlich, M., W. Boll, A. Van Oijen, R. Hariharan, K. Chandran, M. L. Nibert, and T. Kirchhausen. 2004. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits. Cell 118:591-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feire, A. L., H. Koss, and T. Compton. 2004. Cellular integrins function as entry receptors for human cytomegalovirus via a highly conserved disintegrin-like domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:15470-15475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fitzgerald, L. A., M. Poncz, B. Steiner, S. C. Rall, Jr., J. S. Bennett, and D. R. Phillips. 1987. Comparison of cDNA-derived protein sequences of the human fibronectin and vitronectin receptor alpha-subunits and platelet glycoprotein IIb. Biochemistry 26:8158-8165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forrest, J. C., J. A. Campbell, P. Schelling, T. Stehle, and T. S. Dermody. 2003. Structure-function analysis of reovirus binding to junctional adhesion molecule 1. Implications for the mechanism of reovirus attachment. J. Biol. Chem. 278:48434-48444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freed, E. O. 2004. HIV-1 and the host cell: an intimate association. Trends Microbiol. 12:170-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furlong, D. B., M. L. Nibert, and B. N. Fields. 1988. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J. Virol. 62:246-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavrilovskaya, I. N., M. Shepley, R. Shaw, M. H. Ginsberg, and E. R. Mackow. 1998. β3 Integrins mediate the cellular entry of hantaviruses that cause respiratory failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7074-7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Georgi, A., C. Mottola-Hartshorn, A. Warner, B. Fields, and L. B. Chen. 1990. Detection of individual fluorescently labeled reovirions in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:6579-6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graham, K. L., P. Halasz, T. Y., M. J. Hewish, Y. Takada, E. R. Mackow, M. K. Robinson, and B. S. Coulson. 2003. Integrin-using rotaviruses bind α2β1 integrin α2 I domain via VP4 DGE sequence and recognize αXβ2 and αVβ3 by using VP7 during cell entry. J. Virol. 77:9969-9978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guerrero, C. A., E. Mendez, S. Zarate, P. Isa, S. Lopez, and C. F. Arias. 2000. Integrin αvβ3 mediates rotavirus cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14644-14649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hewish, M. J., Y. Takada, and B. S. Coulson. 2000. Integrins α2β1 and α4β1 can mediate SA11 rotavirus attachment and entry into cells. J. Virol. 74:228-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hynes, R. 2002. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110:673-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hynes, R. O. 1992. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell 69:11-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson, T., A. P. Mould, D. Sheppard, and A. M. King. 2002. Integrin αvβ1 is a receptor for foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 76:935-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson, T., D. Sheppard, M. Denyer, W. Blakemore, and A. M. King. 2000. The epithelial integrin αvβ6 is a receptor for foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 74:4949-4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keroack, M., and B. N. Fields. 1986. Viral shedding and transmission between hosts determined by reovirus L2 gene. Science 232:1635-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirchhausen, T., J. S. Bonifacino, and H. Riezman. 1997. Linking cargo to vesicle formation: receptor tail interactions with coat proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9:488-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lechner, F., U. Sahrbacher, T. Suter, K. Frei, M. Brockhaus, U. Koedel, and A. Fontana. 2000. Antibodies to the junctional adhesion molecule cause disruption of endothelial cells and do not prevent leukocyte influx into the meninges after viral or bacterial infection. J. Infect. Dis. 182:978-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leong, J. M., R. S. Fournier, and R. R. Isberg. 1990. Identification of the integrin binding domain of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis invasin protein. EMBO J. 9:1979-1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li, E., S. L. Brown, D. G. Stupack, X. S. Puente, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 2001. Integrin αvβ1 is an adenovirus coreceptor. J. Virol. 75:5405-5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li, E., D. Stupack, R. Klemke, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 1998. Adenovirus endocytosis via αv integrins requires phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase. J. Virol. 72:2055-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu, Y., A. Nusrat, F. J. Schnell, T. A. Reaves, S. Walsh, M. Ponchet, and C. A. Parkos. 2000. Human junction adhesion molecule regulates tight junction resealing in epithelia. J. Cell Sci. 113:2363-2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lortat-Jacob, H., E. Chouin, S. Cusack, and M. J. van Raaij. 2001. Kinetic analysis of adenovirus fiber binding to its receptor reveals an avidity mechanism for trimeric receptor-ligand interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9009-9015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mandell, K. J., B. A. Babbin, A. Nusrat, and C. A. Parkos. 2005. Junctional adhesion molecule-1 (JAM1) regulates epithelial cell morphology through effects on beta 1 integrins and Rap1 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280:11665-11674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin-Padura, I., S. Lostaglio, M. Schneemann, L. Williams, M. Romano, P. Fruscella, C. Panzeri, A. Stoppacciaro, L. Ruco, A. Villa, D. Simmons, and E. Dejana. 1998. Junctional adhesion molecule, a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that distributes at intercellular junctions and modulates monocyte transmigration. J. Cell Biol. 142:117-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mercier, G. T., J. A. Campbell, J. D. Chappell, T. Stehle, T. S. Dermody, and M. A. Barry. 2004. A chimeric adenovirus vector encoding reovirus attachment protein σ1 targets cells expressing junctional adhesion molecule 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:6188-6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naik, M. U., S. A. Mousa, C. A. Parkos, and U. P. Naik. 2003. Signaling through JAM-1 and αvβ3 is required for the angiogenic action of bFGF: dissociation of the JAM-1 and αvβ3 complex. Blood 102:2108-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Odegard, A. L., K. Chandran, X. Zhang, J. S. Parker, T. S. Baker, and M. L. Nibert. 2004. Putative autocleavage of outer capsid protein μ1, allowing release of myristoylated peptide μ1N during particle uncoating, is critical for cell entry by reovirus. J. Virol. 78:8732-8745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Otey, C. A., F. M. Pavalko, and K. Burridge. 1990. An interaction between α-Actinin and the β1 integrin subunit in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 111:721-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozaki, H., K. Ishii, H. Horiuchi, H. Arai, T. Kawamoto, K. Okawa, A. Iwamatsu, and T. Kita. 1999. Cutting edge: combined treatment of TNF-α and IFN-γ causes redistribution of junctional adhesion molecule in human endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 163:553-557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pearse, B. M. 1988. Receptors compete for adaptors found in plasma membrane coated pits. EMBO J. 7:3331-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pfaff, M., S. Liu, D. J. Erle, and M. H. Ginsberg. 1998. Integrin β cytoplasmic domains differentially bind to cytoskeletal proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 273:6104-6109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reinisch, K. M., M. L. Nibert, and S. C. Harrison. 2000. Structure of the reovirus core at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature 404:960-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reszka, A. A., Y. Hayashi, and A. F. Horwitz. 1992. Identification of amino acid sequences in the integrin β1 cytoplasmic domain implicated in cytoskeletal association. J. Cell Biol. 117:1321-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sackstein, R. 2005. The lymphocyte homing receptors: gatekeepers of the multistep paradigm. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 12:444-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schaller, M. D., C. A. Otey, J. D. Hildebrand, and J. T. Parsons. 1995. Focal adhesion kinase and paxillin bind to peptides mimicking β integrin cytoplasmic domains. J. Cell Biol. 130:1181-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seliger, L. S., K. Zheng, and A. J. Shatkin. 1987. Complete nucleotide sequence of reovirus L2 gene and deduced amino acid sequence of viral mRNA guanylyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 262:16289-16293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith, A. E., and A. Helenius. 2004. How viruses enter animal cells. Science 304:237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith, R. E., H. J. Zweerink, and W. K. Joklik. 1969. Polypeptide components of virions, top component and cores of reovirus type 3. Virology 39:791-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stehle, T., and T. S. Dermody. 2003. Structural evidence for common functions and ancestry of the reovirus and adenovirus attachment proteins. Rev. Med. Virol. 13:123-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stehle, T., and T. S. Dermody. 2004. Structural similarities in the cellular receptors used by adenovirus and reovirus. Viral Immunol. 17:129-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sturzenbecker, L. J., M. L. Nibert, D. B. Furlong, and B. N. Fields. 1987. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J. Virol. 61:2351-2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tyler, K. L. 2001. Mammalian reoviruses, p. 1729-1745. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 74.Tyler, K. L., D. A. McPhee, and B. N. Fields. 1986. Distinct pathways of viral spread in the host determined by reovirus S1 gene segment. Science 233:770-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Virgin, H. W., IV, R. Bassel-Duby, B. N. Fields, and K. L. Tyler. 1988. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing). J. Virol. 62:4594-4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weiner, H. L., D. Drayna, D. R. Averill, Jr., and B. N. Fields. 1977. Molecular basis of reovirus virulence: role of the S1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5744-5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weiner, H. L., M. L. Powers, and B. N. Fields. 1980. Absolute linkage of virulence and central nervous system tropism of reoviruses to viral hemagglutinin. J. Infect. Dis. 141:609-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wennerberg, K., L. Lohikangas, D. Gullberg, M. Pfaff, S. Johansson, and R. Fassler. 1996. β1 integrin-dependent and -independent polymerization of fibronectin. J. Cell Biol. 132:227-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wetzel, J. D., J. D. Chappell, A. B. Fogo, and T. S. Dermody. 1997. Efficiency of viral entry determines the capacity of murine erythroleukemia cells to support persistent infections by mammalian reoviruses. J. Virol. 71:299-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wickham, T. J., P. Mathias, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 1993. Integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams, L. A., I. Martin-Padura, E. Dejana, N. Hogg, and D. L. Simmons. 1999. Identification and characterisation of human junctional adhesion molecule (JAM). Mol. Immunol. 36:1175-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zarate, S., P. Romero, R. Espinosa, C. F. Arias, and S. Lopez. 2004. VP7 mediates the interaction of rotaviruses with integrin αvβ3 through a novel integrin-binding site. J. Virol. 78:10839-10847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang, X., J. Tang, S. B. Walker, D. O'hara, M. L. Nibert, R. Duncan, and T. S. Baker. 2005. Structure of avian orthoreovirus virion by electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction. Virology 343:25-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]