Abstract

Purpose

In the transformation of health care systems, the introduction of integrated service networks is considered to be one of the main solutions for enhancing efficiency. In the last few years, a wealth of literature has emerged on the topic of services integration. However, the question of how integrated service networks should be modelled to suit different implementation contexts has barely been touched. To fill that gap, this article presents four models for the organization of mental health integrated networks.

Data sources

The proposed models are drawn from three recently published studies on mental health integrated services in the province of Quebec (Canada) with the author as principal investigator.

Description

Following an explanation of the concept of integrated service network and a description of the Quebec context for mental health networks, the models, applicable in all settings: rural, urban or semi-urban, and metropolitan, and summarized in four figures, are presented.

Discussion and conclusion

To apply the models successfully, the necessity of rallying all the actors of a system, from the strategic, tactical and operational levels, according to the type of integration involved: functional/administrative, clinical and physician-system is highlighted. The importance of formalizing activities among organizations and actors in a network and reinforcing the governing mechanisms at the local level is also underlined. Finally, a number of integration strategies and key conditions of success to operationalize integrated service networks are suggested.

Keywords: integrated service networks, integration strategies, mental health network models, Quebec (Canada) mental health system

Introduction

In highly developed countries, in order to enhance the efficiency of health care systems, the search for better practices and new organizational models is an issue. Because of economic pressures and a succession of failed attempts to improve services coordination, the concept of integrated service networks has recently emerged as a way of structuring health care, particularly for chronic and complex problems. Coordination and continuity of services is an old preoccupation, but what emerged mostly in the 1990s is the idea of creating a network of services linking autonomous health care and social service providers in a given district to treat specific health problems or clienteles such as serious mental health disorders or the frail elderly. Since then, a wealth of literature has been published defining what integrated service networks, also known as organized delivery systems, integrated delivery systems or disease management, are or should be.

Despite the abundance of writings on integrated service networks, few empirical studies have been published [1], and still fewer have explored models to suit the various implementation contexts [2–5]. Leutz's questions such as who should be in charge of integration, the degree of financial and administrative integration needed to achieve clinical integration, and what support structures and processes are needed for integrated service networks require further investigation [6]. There have been significant advances in knowledge concerning factors that facilitate or hinder the development of integrated service networks, but more is required to map out their evolution [7–9].

This article explores the question of the organization of integrated service networks for the serious mental health disorders, based on the Quebec (Canada) context and on three recent research projects conducted in that province. First, the concept of integrated service network will be examined, focusing on fundamental dimensions relevant to its organization. Secondly, the Quebec context underlying integrated mental health service networks will be illustrated. After having outlined our methodology, the presentation of four mental health models of integrated service networks in rural, urban or semi-urban, and metropolitan areas will follow. We will then elaborate on key conditions of, and main obstacles to, the application of those models, referring to the three questions raised by Leutz [6], cited in the preceding paragraph. To conclude, we will look at how these models of integrated service networks in mental health can be applied to other health care sectors and even generalized.

Concept of integrated service networks

As mentioned in the introduction, numerous works have been published on services integration and integrated service networks [5, 10–14]. Services integration has three components: functional/administrative, clinical, and physician-system. The functional/administrative part deals with systems of governance, management, information, resources allocation and evaluation. The clinical one is aimed at improving the continuity of services. It implies care at the vertical and horizontal levels, which means taking into account service needs between different periods of care (i.e. pre- and post- hospitalization) as well as services provided within a period of care (i.e. psychosocial community support, housing and employment). It constitutes the essential aspect of care delivery [15]. The other forms of integration serve to further it. The physician-system component stems from the importance of the physicians’ participation in the network, for they are ultimately clinically responsible for the care given [5, 6, 16]. Therefore, integration affects all components of a system. It involves restructuring clinical practices for the clientele and the relationships between health care professionals, service lines and organizations at the different levels of governance: strategic (upper management), tactical (middle management) and operational (staff). The concept of network brings a territorial dimension to the idea of integration, and pertains to the organization of services for a specific health sector. All organizations involved in a given area and with a targeted clientele will thus be mobilized to coordinate their action. Depending on client and resources volume, networks may serve one or more local districts. Integrated service networks are based on an acknowledgement of considerable interdependence among the actors and organizations in a given district and sector of intervention. On a continuum of intensity of inter-organizational relationships (e.g. partnership, mutual adjustment), integrated service networks constitute one of the most advanced and formalized forms of coordination between independent organizations [17]. They involve rationalization in order to provide a diversified range of services to meet client needs [18]. In the literature, they correspond to the virtual integration usually viewed as more effective for complex systems that present a high degree of diversification [19]. Virtual integration nonetheless poses major challenges in terms of managing coherence and coordination. The situation is all the more evident in the health care sector, where organizations are viewed as professional bureaucracies with unclear goals and fluid and ambiguous authority [20].

To implement functional/administrative, clinical and physician-system integration, a number of strategies are identified. Integration strategies are mechanisms or processes to promote more coherent, coordinated and efficient services in a network [13, 14, 18, 21–23]. Functional/administrative strategies aim at, for example, reducing services duplication, increasing flexibility in resources allocation so as to finance organizations in a network that offer more cost-effective interventions, improving and relating clinical information between organizations and better controlling the system. In functional/administrative integration, we find strategies such as electronic client information and management systems as well as methods for allocating and managing material, financial and personnel resources. Planning, inter-organizational protocols (memorandum of understanding), grouping of institutions and a single point of entry are featured as well. The way governance is structured is a key element for good network functioning [24, 25]. At the clinical level, the importance of creating a network is based on the actors’ interest in: (a) sharing skills and knowledge regarding a clientele difficult to treat and involving various types of clinical staff and organizations; (b) building peer support that may encompass diversified skills; (c) reinforcing consultation or sharing expertise and support among various lines of services; (d) becoming more familiar with a district's resources in order to better refer clientele; (e) clarifying organizations’ missions and their referral processes, particularly appointing liaison officers to facilitate continuity; (f) identifying key staff members to whom clients can be referred according to their needs; (g) developing common tools for the network; and (h) for more complex cases, facilitating joint interventions among professionals from different organizations. Clinical integration strategies involve case managers, key staff1 and liaison officers. They include community follow-up, shared care, continuing education, clinical coaching, inter-organizational internships and programs, shared staff, and individualized service plans [11]. Additional provision includes: follow-up protocols that help standardize and rationalize practices [11], common electronic needs assessment grids and confidentiality protocols that allow for inter-organization exchange of information on clients, and so on. Community follow-up may vary in intensity and imply staff workers from one or more organizations. Shared care consists in support provided by psychiatrists to general practitioners treating clients with mental health problems. An example of inter-organizational program would be crisis services provided jointly by a local community centre and a community organization. Those integration strategies are crucial considering that integrated service networks involve sweeping changes in the organization of the health care system, in inter-organizational practices and in the delivery of services [26].

Context underlying Quebec's mental health integrated service networks

The Canadian health care system is under provincial jurisdiction. It is mainly public, with extensive private sector collaboration (e.g. residential/nursing-home services, dental and optometric services, pharmacists). In the province of Quebec, health and social services come under a single authority. Control over that system is the responsibility of two regulatory bodies: the Ministry of Health and Social Services and the Regional agencies. The Ministry defines the strategic functions of the system, establishes the main rules governing its operations and distributes resources equitably among regions. It also retains some important functions in managing the health care system, such as developing guidelines for human, material and financial resources, enacting labour force adjustment policies and programs, and organizing training and research. The Regional agencies, numbering eighteen for nineteen health and social services regions, are responsible for planning, organizing, coordinating, budgeting and evaluating health care and social services in their respective regions. They manage the health care system from local districts and on the basis of nine programs or clienteles (e.g. physical, mental and public health, physical and mental disabilities, the frail elderly). Thus, the system is relatively decentralized at the regional level, despite the fact that on one side, the Ministry holds strategic responsibilities and that on the other side, the local health care organizations retain a high degree of autonomy by handling such responsibilities as overall budget management.

The idea of ensuring greater coherence and coordination among organizations that deliver health services based on programs for specific clienteles in a given district emerged in Quebec around 1990. The mental health program spearheaded that approach. At that time, strategies for integrating services were developed through regional planning and regional and local coordination committees [27, 28]. The mid-1990s witnessed extensive mergers of institutions, which became the main approach in achieving better integration of the health and welfare system. Through mergers, the 917 Quebec health care establishments that made up the system in 1990 were reduced to 478 by 2001 [29]. Implementation of integrated service networks went into full swing between 1997 and 2001, owing to non-recurrent funding granted by the federal government to encourage innovation and system efficiency. Owing to those funds, a number of integrated networks emerged for complex or chronic health problems, notably for the frail elderly, for type 2 diabetics and for cancer patients [30]. In parallel to the federal initiative, provincial policies were elaborated to promote integrated service networks for clienteles needing multiple services on an intensive basis for a substantive period of time [31]. In the policy-makers’ views, such an organization of services allows for better client follow-up and response to people's needs, ensures efficiency in the system by reducing duplication of services and encourages providers to work in coordination. In that context, the development of integrated service networks for people with serious mental health disorders was emphasized. Several ministerial documents testify to that orientation [31–33]. Beside some broad guidelines such as implementing a basic range of diversified services, the way networks should develop rests on regional or local initiative. No timescale, incentive or follow-up of the policy implementation was specifically given by the government to promote integrated service networks for that clientele. Such a situation compromised network implementation and favoured a high degree of diversification among regions, most of the local districts having in fact barely implemented them [27].

The degree of integration of mental health networks then relied mostly on the leadership of Regional agencies and local providers. In Quebec, mental health networks basically include: local community centres (literally known as CLSCs: local community services centres), community organizations, private medical clinics and intersectoral resources. Depending on the area, they may involve of general hospital psychiatric departments and psychiatric hospitals. Local community centres offer primary care on a short-term basis, homemaker assistance, and health promotion programs. Some of them have recently added specialized services on a long-term basis such as community follow-up and treatment programs for people suffering from serious mental health disorders. Community organizations provide programs like follow-up, self-help for peers or family, support for workforce integration, short or medium term housing or help in finding housing, hot-line services or crisis counselling, rehabilitation services such as workshops and day centres, and recreational activities. As for private medical clinics, an Ontario study reveals that fifty percent of people with mental health problems are treated exclusively by a general practitioner [34]. This shows the importance of private medical clinics as partners in integrated service networks. The primarily solicited intersectoral resources for mental health networking are municipalities (for welfare housing), school boards, the justice system, the police force, employment centres, food banks and soup kitchens, and so on. Specifically found in general hospital psychiatric departments are short-term hospitalizations, day clinics, outpatient clinics and community treatment programs usually assertive. What psychiatric hospitals add to that is the ultra-specialized care handling of the most serious cases, long-term hospitalizations, co-morbidity programs, ultra-specialized clinics, training and advanced research.

Methodology

This article is based on three interrelated research projects on mental health integrated service networks in the province of Quebec (Canada) funded by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the “Fonds de recherche en santé du Québec” and the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services (2002–2004). The projects were divided into three phases and conducted simultaneously. The first phase was designed to assess the implementation level of mental health integrated service networks and identify examples viable in different implementation contexts. It encompassed all Quebec regions. Lengthy interviews (n=18) were conducted with managers of the mental health program in each Regional agency.

The second phase aimed at outlining the most effective strategies to operate integrated networks and the elements that facilitate or hinder their development. In that phase, case studies [35] were conducted. The case study method was considered the most appropriate because it allows for a deep understanding of a phenomenon and takes into account its multidimensional aspects: political, cultural, financial and so on [36, 37]. A case study is an empirical inquiry in which the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident. Six local networks in five of the health and social services regions in Quebec were selected based on the results of the first phase. The six networks were chosen, by the research team including its decision-making partners at the provincial and regional levels, because of their representativeness of the province's integrated service networks on the whole. The selection criteria were: the extent to which the networks reflected rural, urban or semi-urban, and metropolitan characteristics; their high degree of implementation; the existence or the absence of a psychiatric hospital in the area; and the feasibility of the research: practical considerations such as the remoteness of the networks. The third phase, not considered in this article, is an evaluation of the effectiveness of the six local services networks in response to the needs of people with serious mental health disorders.

The six cases, described largely in a recently published report [38], are grounded on extensive sources of qualitative and quantitative data. This article is essentially based on the qualitative part of the collected information. It is justified by its descriptive character, presenting ideal-types or models of integrated service networks suitable for different contexts and discussing their implementation and generalization. The qualitative data of the cases come from four sources: 1. primary sources (i.e. administrative documents at the organizational and local levels; regional and ministerial policies), 2. secondary sources (mental health, organizational theory and network literature), 3. participant observation in the networks governance structures (n=32) and 4. individual interviews conducted with 275 managers and clinical staff representative of all organizations belonging to the six networks, 50 service users and 25 of their relatives. The organizations considered are the ones involved in the mental health system mentioned in the previous section: local community centres, community organizations, intersectoral resources, general hospital departments, psychiatric hospitals and private medical clinics. The respondents were selected by using an intentional sampling strategy [39], and were interviewed from the winter of 2002 to the summer of 2004. The interviews were recorded, and all the data collected were summarized using analytical grids that included, among others, the range of networks resources, the types of integration strategies, inter-organizational relationships and factors that facilitate or hinder network implementation. The cases were then studied by content analysis to construct models relevant to rural, semi-urban or urban and metropolitan contexts. The results were validated by the research team and its decision-making partners at the provincial and regional levels.

Models of integrated service networks

We now introduce the four proposed models for integrated service networks. The first two apply to rural settings, the third to an urban or semi-urban one and the last to a metropolitan area. Depending on whether they are rural or metropolitan, the networks include approximately 20,000 to 200,000 people. In Quebec, as elsewhere in the world, between 2 and 3% of the population face serious mental health disorders (e.g. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder). That is the clientele targeted by the networks. Each presentation begins with the local features determining the model to be adopted, and focuses on the governance structure and integration strategies.

Rural models

Rural settings are characterized by a scarcity of resources scattered on a large territory. The population is more confined than in an urban or semi-urban environment. In addition, rural resources are not very specialized. More often than not there is no hospital. In rural Quebec, the most available resources are a local community centre, community organizations, private medical clinics, and intersectoral resources (e.g. police, the school board for training programs). The type of medical practice is not unlike the family medicine pattern. A tradition of collaboration and mutual assistance exists more than in other settings. The more manageable size of the network is also an advantage for implementing integrated service networks.

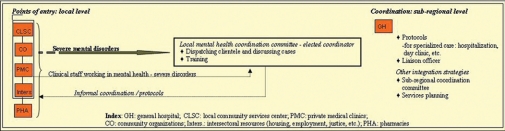

Figures 1 and 2 both show models of integrated service networks in rural areas. The difference between them is the availability of specialized services offered by a hospital and the main integration strategy selected for the organization of the network. Figure 1 illustrates the model without a hospital and in which the main integration strategy is a local mental health coordination committee. That committee brings together all the clinical staff from the local community centre, community organizations, intersectoral resources and private medical clinics involved in serving clients with serious mental health disorders. An elected official, usually from the local community centre, coordinates the committee's activities. Cases requiring follow-up are distributed, and clinical discussions take place. Committee members may agree to jointly follow a client. To cover specialized services, a protocol (memorandum of understanding) is established between the local community centre and a psychiatric department in one of the region's hospitals. Protocols are also elaborated with pharmacies for better medication control.

Figure 1.

Model #1 for an integrated service network in a rural setting.

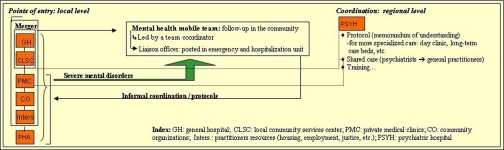

Figure 2.

Model #2 of an integrated service network in a rural setting.

The Figure 2 model represents a more diversified service network because the district has a general hospital, although without a psychiatric department. This model is structured around a mobile mental health team made up of clinical staff administratively attached to a local community centre or a hospital, and coordinated by a local community centre officer. In this particular case, the team's creation and operations were facilitated by the merger of the hospital and the local community centre. The mental health mobile team offers treatment and community follow-up of varying intensity. Through protocols or informal coordinating links, it also ensures referrals and coordination of services with activities offered by other agencies such as community organizations, private medical clinics and intersectoral resources. As in Figure 1, protocols are signed with pharmacies for medication control. Concerning emergencies and hospitalization, there are close ties between the mobile mental health team and the hospital team. A member of the mobile mental health team who is based at the hospital liaises with the hospital staff, the rest of the team and the general practitioners. To help the district's mental health team in providing more specialized services, strong cooperation exists between the merged hospital-local community centre and the psychiatric hospital located in another network of the same region. A protocol allows for the transfer of clientele to the psychiatric hospital for medium or long-term hospitalization and for specialized services such as those given in a day clinic. It also allows a psychiatrist to come for one or two days per month to handle difficult cases and consult with the general practitioners and the mobile mental health team (i.e. shared care practices). In the Figure 1 and 2 models, integration strategies such as regional and local mental health planning and regional coordinating committees are also put forward so as to insure coherence and equity between the localities of a given region.

Urban or semi-urban model

Compared to rural settings, semi-urban and urban local districts are characterized by a more extensive, diversified, and for urban territories, geographically concentrated range of resources. They have a general hospital with a psychiatric department, and there is usually no psychiatric hospital. Some general hospitals and community organizations have a regional mandate. People are less confined to a given territory and tend to shop around for services in adjacent areas. Such a situation makes the geographic divisions more fluid compared to rural areas.

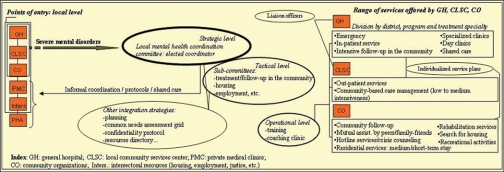

Figure 3 introduces a model for organizing services in integrated networks in urban and semi-urban settings. As with the Figure 1 model, the integrated service network is structured around a central strategy: a local mental health coordination committee that involves senior administrators from the hospital, the local community centre and community organizations involved in mental health. These people embody governance at the strategic level.

Figure 3.

Model for an integrated service network in an urban or semi-urban setting.

Given the number of actors involved in the network, other integrating strategies are introduced. At the tactical level, service coordinators sit at sub-committees set up to work on specific health-related issues such as treatments, follow-up in the community and job integration. These sub-committees are required to develop strategies and common tools that facilitate work in an integrated network, for example common needs assessment grids, confidentiality agreements to transfer information between organizations and a resources directory. For large organizations such as hospitals and local community centres, liaison officers ensure the working of inter-organization links and clientele follow-up. At the operational level, the field staff is encouraged to elaborate individualized services plans and practices such as case management or assertive community treatment. It is also targeted for inter-organizational and inter-professional training, clinical coaching and internships or staff exchanges. The objective is to guarantee the acquisition of best practices knowledge, meet staff from the network, and instil a culture of partnership.

The integrated strategies already outlined in the urban and semi-urban model apply to the first three points of entry in Figure 3 the general hospital, the local community centre (CLSC) and the community organizations. The last three points of entry: private medical clinics, pharmacies and intersectoral resources, are required to cooperate with the mental health network through informal coordination, protocols or shared-care initiatives. They are invited to the local coordination committee meetings on specific topics related to their mission and their expertise.

Metropolitan model

A metropolitan setting is similar to an urban one, except that the overall features characterizing the latter are magnified: geographic concentration, diversification and proliferation of resources, and population mobility. Psychiatric hospitals are available. They give the distinctive characters to the organization of services, because of the ultra-specialized care they offer. If in the vicinity there is also a general hospital with a psychiatric department they may regroup for rationalization purposes (e.g. psychiatric emergency services at the general hospital and specialized clinics at the psychiatric hospital). Compared to rural and urban or semi-urban districts, metropolitan areas have socio-demographic and economic features conducive to the organization of services encompassing several localities due to the supra-local mission of the psychiatric hospital.

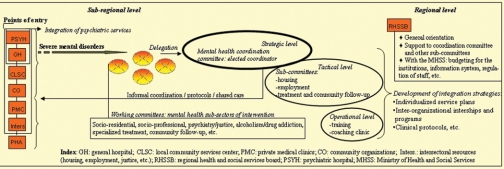

Figure 4 presents a model similar to the one illustrated in Figure 3, except for an intermediary structure (the small crossed circles in front of the oval in bold) preceding the mental health coordination committee. The organization of the metropolitan model rests on a matrix organization of services that takes into account the strategic, tactical and operational levels of governance as well as distinct spheres of intervention such as treatment and hospitalization, support in the community, housing and employment. Due to the large number of actors to mobilize, the intermediary structure brings coherence and coordination into those different spheres of intervention. In fact, it creates an integrated network within each of them. Moreover, a delegation of actors from each sphere is appointed to coordinate their own actions with the mental health coordination committee at the strategic level.

Figure 4.

Model of an integrated service network in a metropolitan setting.

Discussion: key conditions for and main obstacles to the operationalization of the four models of integrated service networks

In terms of complexity, the rural model is, not surprisingly, the easiest to implement. Because of the small number of actors involved, the network is more manageable. The scarcity of resources forces organizations to cooperate, favouring the recognition of interdependence, legitimacy and expertise of the partners, conditions required for the implementation of integrated service networks [28, 40]. The collaborative culture of rural settings has been highlighted in other studies and in health integrated networks introduced in Quebec [41–43]. In rural settings, power between organizations is also more balanced than in urban or semi-urban and metropolitan areas, where a general or a psychiatric hospital plays a leading role. Dispersion of power between organizations has been found to facilitate networking; otherwise small organizations tend to benefit from the network, leaving larger units less interested in cooperation [27, 38, 40, 44]. In Quebec as in other settings [45], the result is that networks often essentially include local community centres and community organizations, with hospitals weakly linked to both. Finally, in rural districts, the fact that clients cannot easily shop around for services induces them to adhere to their local network. For the success of integrated networks implementation, the ways of organizing networks are crucial, but so are the utilization patterns of the clientele [46–48]. Consequently, two perspectives have to be taken into account in modelling integrated service networks: the organizations’ perspective and the population's perspective. In this article, we address the first one only. The complexity of the health networks in urban or semi-urban and metropolitan districts encourages the development of more numerous integration strategies than in rural settings. The types of integration (functional-administrative, clinical and physician-system) which are related to the levels of governance help to manage the complexity of those settings, and are thus relevant to answer the first of the three questions put forward by Leutz, cited in the introduction of this article [6]: “Who should be in charge of integration?”. The strategic governing level of the system (i.e. the Ministry, the Regional agencies and the local networks organizations’ upper management), addressing mostly the functional or administrative integration, is the one that can change the labour force rules and group organizations. It can put forward inter-organizational protocols, strategic planning and computerized information for the network. The tactical level of governing (e.g. program coordinators and division heads) is the most suitably positioned to ensure best practices for the clinical integration of the clientele, such as utilization of clinical protocols, liaison officer, community follow-up, shared care, etc. The health care system being a professional bureaucracy [49], the mobilization of the operational level (i.e. the field staff) is also critical in the implementation of integrated networks. Training, clinical coaching, inter-organizational internships and staff involvement in decision making are facilitating elements for improving collaboration and system changes. Therefore, all three levels of governance have to be interrelated in the management of a network. Our integration models have pointed out the importance of the coordinating committee including sub-committees in playing such a role.

The coordinating committee is the cornerstone of the network integration process by developing and monitoring integration strategies, enhancing a collaborative culture, and solving potential conflicts. But for networks without a history of collaborative culture and for complex networks such as in urban or semi-urban and metropolitan settings, our research projects underline that coordinating committees are inefficient if given an unclear mandate and little power. In that case, networks will often not be very developed in terms of integration. The coordinating committees are restricted to a role of exchanging information while the organizations involved in the network continue to serve their own corporate objectives. For the development of complex networks, our observations then underscore the importance of enhancing substantially the decision-making power and control of the central coordinating committee. Moreover, the most successful Quebec regions in the implementation of integrated mental health services have benefited from firm policy directions promoting networks by the Ministry and the Regional agencies.

Our studies also help to answer Leutz's second question [6]. “Which degree of financial and administrative integration is required to achieve effective clinical service integration?” First, total integration of the organizations’ administrative and financial structures means vertical integration of the system. The literature on the impact of mergers is not necessarily flattering: It describes a loss of innovation and flexibility, reduced diversification, heavier bureaucracy, and for the organizations forced to merge, major conflicts and discouragement among staff, and a transformation of the system in favour of the culture of the dominant organization [2, 50]. Ownership-based integration, however, can reduce transaction costs between separate production processes, produce economies of scope and scale, and facilitate imposition of common information and clinical practice standards [51]. We have already mentioned that virtual integration is usually viewed as more effective for complex systems that present a high degree of diversification [19]. In Quebec, the health care organizations’ mode of financing, based on global budgeting, and the current ways of assessing their performance on an individual basis, do not help to integrate clinical services effectively [52]. They prevent taking into consideration the client's health continuum of services. It is in the nature of an organization to grow without considering the efficiency of the whole system, and its performance indicators do not necessarily reflect a network mode of organization (e.g. pressure to reduce length of stays in hospital may have the counter-effect of boosting premature departures and re-admissions, and do not necessarily take into account the essential resources for post-hospital follow-up). Consequently, we believe that where there is a collaborative culture, a network can achieve quite a good clinical integration, specifically in rural districts without much degree of financial and administrative integration. But for urban or semi-urban and metropolitan settings, due to the complexity of such systems, financial integration between some organizations or by health sector, in this case mental health care, and administrative integration, are crucial for achieving a high degree of clinical integration.

Leutz's third and last question: [6], “What support structures and processes are needed to implement integrated service networks?” has been at the core of this article. While informal relations such as trust and commitment of the actors involved, play a fundamental role in structuring networks [53], we suggest that to succeed in complex settings, the development of integrated service networks involves orchestrating an extensive number of strategies in the administrative/functional, clinical and physician-system types of integration and at strategic, tactical and operational governing levels. The integration strategies encourage new interactions between parties that increase practices in favour of the reform. We have underscored many potential integration strategies, including governance mechanisms. The integrated services intensity reached by a network depends on the coherence and scope covered by those strategies.

Finally, the complexity of the health care system, particularly in mental health, the scarcity of resources specifically offered in the community, and the overall difficulty in implementing reforms require to be addressed. The health care system is known as one of the most complex systems to manage [16]. For implementing integrated service networks for instance, reforms have to be synchronized at different levels of governance: the Ministry, Regional agencies, local and organizational levels. Several regulatory logics also interact, which make goals and lines of authority fluid: bureaucratic, professional, managerial, political, etc. [54]. Organizations are not necessarily divided by health sector or district territory, making it more difficult to implement integrated service networks. In mental health specifically, because of historical ideological clashes between psychiatry and some community organizations offering alternatives to psychiatry, the development of integrated service networks has not been easily achieved. The scarcity of resources offered in the community makes it also more difficult to integrate services into networks. Milward and Provan [18] have underlined the crucial impact of the availability of resources in the integrate services networks’ effectiveness. Lastly, change has to be carefully planned and strategies to support the implementation of reforms highly developed. Authors in organizational change have increased our awareness on the importance of the phenomenon of resistance to change that must be overcome in a reform process [9, 55, 56]. For successfully implementing integrated service networks, all partners must for instance recognize common problems of system functioning, share a compatible vision, have interest in collaborating and acknowledge gains to be made from cooperation [9, 28, 57].

Conclusion

Integrated service networks are an organizational model that requires tight coordination among organizations and staff from a given health sector and district. They involve major interdependence between organizations and staffs that interact with a clientele whose health problems are complex and often chronic. This article has demonstrated the importance of structuring those networks to suit the context in which they are implemented: rural, urban or semi-urban and metropolitan. It has also stressed the relevance of mobilizing the health care staff according to functional/administrative, clinical and physician-system integration types and strategic, tactical, and operational governance levels. The importance of formalizing integration within a network, allowing for more enduring coordination, particularly by reinforcing the governance mechanisms at the local level, has been underscored. To reach such formalization, a number of strategies and models for integrated service networks have been presented. Keys to their success and obstacles to their operationalization have also been illustrated. The integrated service networks face two issues: how to efficiently organize services to suit contexts and how to implement them.

Because of the high degree of intensity involved, integrated service networks are thus not suitable for all health care sectors. In Quebec, they are mostly implemented in the following areas: serious mental health disorders, the frail elderly, youth with behavioural problems, physical or intellectual disabilities such as cranial-cerebral disorders and type 2 diabetes, and physical health problems for instance in oncology and palliative care. These networks may be more or less complex to organize depending on: (a) the number and type of organizations involved in the health and social fields; (b) the network centrality, defined as the concentration of services given by, and inter-organizational transactions related to, one or some organizations in a network; (c) the transformations required; and (d) the consensus on intervention practices or the conflicting nature of the inter-organizational dynamics. Serious mental health disorders offer an interesting illustration of integrated service networks, as it is, in our view, one of the most complex health sectors to manage not withstanding cases involving dual or triple health issues such as mental disorders, drug addiction and homelessness, or all of those.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the “Fonds de recherche en santé du Québec” and the Ministry of Health and Social Services, which provided financial support for the research projects. Our gratitude also extends to all the participants and decision-making partners involved in those studies, and to the anonymous reviewers. Finally, the contribution of the projects co-researchers have to be outlined, specifically: Alain Lesage, Céline Mercier, Youcef Ouadahi, Guy Grenier, Michel Perreault, Denise Aubé and Linda Cazale.

Footnotes

A key staff worker is a person designated by a service user as the most significant one in his/her process of integrating the community or recovering. Contrary to the case manager, the key staff worker does not necessarily have the role of coordinating services for a user.

Reviewers

Giel J.M. Hutschemaekers, PhD, Professor at the Radboud University of Nijmegen's Academic Centre for Social Sciences (The Netherlands) and director of GRIP (Gelderse Roos Research Institute for mental health care professionalization) Arnhem, The Netherlands.

Mary E. Wiktorowicz, PhD, Associate Professor School of Health Policy and Management, Atkinson Faculty of Liberal & Professional Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Jenny Secker, PhD, Professor of Mental Health, Anglia Polytechnic University & South Essex Partnership NHS Trust, United Kingdom.

Vitae

Marie-Josée Fleury, PhD, Associate Professor, is assistant professor at McGill University's department of psychiatry. She is also adjunct professor at the Université de Montréal's department of health administration and researcher at the Douglas Research Center. Her fields of expertise include organizational analysis and health services evaluation. She is currently directing several projects on mental health integrated service networks.

References

- 1.Leatt P, Nickoloff B. Managing change: implications of current health reforms on the hospital sector. Prepared for the Ontario Hospital Association. 2001:1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman L, Goes J. Why integrated health networks have failed. Frontiers of Health Services Management. 2001;17(4):3–28. 51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park SH. Managing an interorganizational network: a framework of the institutional mechanism for network control. Organization Studies. 1996;17(5):795–824. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provan KG. Services integration for vulnerable populations: lessons from community mental health. Family & Community Health. 1997;19(4):19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA. The new world of managed care: creating organized delivery systems. Health Affairs. 1994;13(5):46–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.13.5.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. The Milbank Quarterly. 1999;77(1):77–110. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleury M-J, Ouadahi Y. Stratégies d'intégration, régulation et moteur de l'implantation de changement. Santé mentale au Québec. 2002;27(2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leggat SG. From the bottom up and other lessons form down under. Healthcare Papers. 2000;1(2):37–47. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2000.17217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA, Morgan-Erickson K, Mitchell JB. Integrating health care delivery. Healthcare Forum Journal. 2000 Dec;:35–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolland JM, Wilson JV. Three faces of integrative coordination: a model of interorganizational relations in community-based health and human services. Health Services Research. 1994;29(3):341–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleury M-J, Mercier C. Integrated local networks as a model for organizing mental health services. Administration & Policy in Mental Health. 2002;1:55–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1021227600823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman HH, Morrissey JP, Ridgely MS. Form and function of mental health authorities at RWJ foundation program sites: preliminary observations. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1990;41(11):1222–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.11.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Provan KG, Milward HB. Integration of community-based services for the severely mentally and the structure of public funding: a comparison of four systems. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1994;9(4):865–95. doi: 10.1215/03616878-19-4-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randolph F, Blasinsky M, Leginski W, Parker LB, Goldman HH. Creating integrated service systems for homeless persons with mental illness: the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48(3):369–73. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conrad DA, Shortell SM. Integrated health systems: promise and performance. Frontiers of Health Services Management. 1996;13(1):3–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glouberman S, Mintzberg H. Managing the care of health and the cure of disease – Part I: differentiation. Health Care Management Review. 2001;26(1):56–69. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whetten DA. Interorganizational relations: a review of the field. Journal of Higher Education. 1981;52(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milward HB, Provan KG. A preliminary theory of interorganizational network effectiveness: a comparative study of four community mental health systems. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1995;40:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walston SL, Kimberly JR, Burns LR. Owned vertical integration and health care: promise and performance. Health Care Management Review. 1996;21(1):83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen MD, Marsh JG, Olsen JP. A garbage can model of organizational choice. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1972;17(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charns MP. Organization design of integrated delivery systems. Hospital & Health Services Administration. 1997;42(3):411–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoge MA, Howenstine RA. Organizational development strategies for integrating mental health services. Community Mental Health Journal. 1997;33(3):175–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1025044225835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mechanic D. Strategies for integrating public mental health services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1991;42(8):797–801. doi: 10.1176/ps.42.8.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackerman FK. The movement toward vertically integrated regional health systems. Health Care Management Review. 1992;17(3):81–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell SM, Shortell SM. The governance and management of effective community health partnerships: a typology for research, policy, and practice. The Milbank Quarterly. 2000;78(2):241–89. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shortell SM, Bazzoli GJ, Dubbs NL, Kralovec P. Classifying health networks and systems: managerial and policy implications. Health Care Management Review. 2000;25(4):9–17. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleury M-J, Denis J-L, Sicotte C. The role of regional planning and management strategies in the transformation of the healthcare system. Health Services Management Research. 2003;16:56–69. doi: 10.1258/095148403762539149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleury M-J, Mercier C, Denis J-L. Regional planning implementation and its impact on integration of a mental health care network. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2002;17(4):1–19. doi: 10.1002/hpm.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) Évolution du nombre d'établissements publics et privés dans le réseau sociosanitaire québécois. Direction générale de la planification stratégique et de l'évaluation, Direction de la gestion de l, Service de développement de l'information. Gouvernement du Québec; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) De l'innovation au Changement. FASS; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministère de la santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) Commission d'étude sur les services de santé et les services sociaux, rapport et recommandations. Commission Clair, Gouvernement du Québec; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) Plan d'action pour la transformation des services de santé mentale. Gouvernement du Québec: Québec; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) Lignes directrices pour l'implantation de réseaux locaux de services intégrés en santé mentale. 2002

- 34.Kates N, Craven MA, Crustolo AM, Nikolaou L, Allen C, Farrar S. Sharing care: the psychiatrist in the family physicians's office. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42:960–5. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin RK. 2nd ed. Vol. 5. Thousand Oaks/London/New Delhi: Sage Publications, International Educational and Professional Publisher; 1994. Case Study Research. Design and Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferlie E, Bennett CL. Patterns of strategic change in health care: district health authorities respond to aids. British Journal of Management. 1992;3:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knights D, Murray F, Willmott H. Networking as knowledge work: a study of strategic inter-organizational developement in the financial services industry. Journal of Management Studies. 1993;30(6):975–95. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleury M-J, Mercier C, Lesage A, Ouadahi Y, Grenier G, Aubé D, Perreault M, Poirier L-R. Réseaux intégrés de services et réponse aux besoins des personnes avec des troubles graves de santé mentale. [Integrated services networks and their response to the needs of people with serious mental health problems [Online]]. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) 2004 Nov; Available from: URL: http://www.chsrf.ca/final_research/ogc/fluery_e.php. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. California: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gray B. Conditions facilitating interorganizational collaboration. Human Relations. 1985;3(10):911–36. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calloway M, Fried B, Johnsen M, Morrissey J. Characterization of rural mental health service systems. Journal of Rural Health. 1999;15(3):296–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1999.tb00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leatt P. The Health Transition Fund: Integrated service delivery. Ottawa: The Fund; 2002. ((Synthesis series)). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) Transformation des services de santé mentale. État d'avancement du plan d'action de décembre 1998. Gouvernement du Québec: Québec; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamarche PA, Lamothe L, Bégin C, Léger M, Vallières-joly M. L'intégration des services: enjeux structurels et organisationnels ou humains et cliniques? Ruptures, revue transdisciplinaire en santé. 2001;8(2):71–92. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malcolm L, Barnett P. Decentralisation, integration and accountability: perceptions of New Zealand's top health service managers. Health Services Management Research. 1995;8(2):121–34. doi: 10.1177/095148489500800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogers A, Sheaff R. Formal and informal systems of primary healthcare in an integrated system: evidence from the United Kingdom. Healthcare Papers. 2000;1(2):47–57. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2000.17218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wacker DP, Fromm-Steege L, Berg WK, Flynn TH. Supported employment as an intervention package: a preliminary analysis of functional variables. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1989;22(4):429–39. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1989.22-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ware NC, Tugenberg T, Dickey B, McHorney CA. An ethnographic study of the meaning of continuity of care in mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(3):395–400. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mintzberg H. Les nouveaux rôles de la planification, des plans et des planificateurs. Gestion. 1994 mai:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weil TP. Management of integrated delivery systems in the next decade. Health Care Management Review. 2000;25(3):9–23. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leatt P, Pink GH, Guerriere M. Towards a Canadian model of integrated healthcare. Healthcare Papers. 2000;1(2):13–37. doi: 10.12927/hcpap..17216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lemay A. L'élaboration d'une démarche d'analyse de la performance valide pour la prise de décision: un enjeu complexe. Ruptures, revue transdisciplinaire en santé. 1999;6(1):67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raak A van, Mur-Veeman I, Paulus A. Understanding the feasibility of integrated care: a rival viewpoint on the influence of actions and the institutionel context. International Journal of Health Planning & Management. 1999;14:235–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1751(199907/09)14:3<235::AID-HPM552>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Contandriopoulos A-P. Réformer le système de santé: une utopie pour sortir d'un statu quo impossible. Ruptures, revue transdisciplinaire en santé. 1994;1(1):8–26. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matland RE. Synthesizing the implementation literature: the ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 1995;5(2):145–74. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pressman JL, Wildavsky A. Implementation: how great expectations in Washington are dashed in Oakland: or, why it's amazing that federal programs work at all, this being a saga of the economic development administration as told by two sympathetic observers who seek to build morals on a foundation of ruined hopes. Berkeley, Los Angeles California: University of California Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gray B, Phillips S. Medical sociology and health policy: where are the connections. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995 Spec No:170–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]