Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this survey is to explore perceived gender differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Methods

Online Harris Interactive interviews were conducted with 1797 adults (general public), 541 parents of children with ADHD, 550 teachers, and 346 children aged 12 to 17 years with ADHD. Responses were examined to determine perceptions of ADHD.

Results

Most of the general public (58%) and teachers (82%) think ADHD is more prevalent in boys. The general public and teachers think boys with ADHD are more likely than girls to have behavioral problems (public: 52% vs 26%; teachers: 36% vs 18%, respectively), while girls with ADHD are thought to have less noticeable problems than boys, such as being inattentive (public: 19% vs 11%; teachers: 29% vs 10%, respectively) or feeling depressed (public: 16% vs 1%; teachers: 12% vs 0.0%, respectively). Four out of 10 teachers report more difficulty in recognizing ADHD symptoms in girls. An overwhelming majority of teachers (85%) and more than half of the public (57%) and parents (54%) think girls with ADHD are more likely to remain undiagnosed. ADHD was reported to have a negative effect on self-esteem, more so in girls. Girls who were taking medication for their ADHD were nearly 3 times more likely to report antidepressant treatment prior to their ADHD diagnosis. Girls were more likely to feel it was “very difficult” to focus on schoolwork and get along with parents.

Conclusions

Survey responses suggest that gender has important implications in the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. Responses by ADHD patients demonstrate gender-specific differences in the personal experience of the condition. Future prospective clinical trials are warranted to clarify the unique needs and characteristics of girls with ADHD.

Introduction

ADHD is a well-recognized, chronic behavioral disorder that is characterized by persistent symptoms of impulsivity, hyperactivity, and/or inattention and is frequently diagnosed during childhood.[1] According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, Fourth Edition, ADHD is defined as the presence of at least 6 symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity that persist for at least 6 months in a way that is maladaptive or developmentally inappropriate. Symptoms of inattention include poor attention to details, limited attention span during tasks or play, forgetfulness, distractibility, and failure to finish assigned activities. Symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity include fidgeting, extreme restlessness, excessive motor activity, difficulty taking turns, and a tendency to blurt out answers or interrupt others. In order to meet diagnostic criteria, the symptoms of ADHD must cause clinically significant impairment in school and at home.[1] With an estimated prevalence of 4% to 12% in school-age children, ADHD is believed to be more common in males.[2] Male-female ratios range from 9:1 to 6:1 in clinical samples but are about 3:1 in community-based population studies.[3]

There may be several reasons for the disparity between male-female ratios in clinical and community-based studies. Clinical samples only capture patients who have been referred for treatment, whereas population samples are more representative of the true prevalence and characteristics of ADHD. Clinical samples are therefore more likely to be biased toward more severe, easily recognized cases, whereas community samples are more likely to include a range of severities and clinical presentations. Because girls tend to be inattentive rather than hyperactive/impulsive,[4,5] they may not be captured by diagnostic criteria that focus primarily on the excess kinetic activity and disruptiveness typical of boys with ADHD, and therefore may not be recognized in the community setting. Also, girls with ADHD are less likely than boys with ADHD to exhibit conduct disorder, aggression, or delinquency, so they are less likely to be referred for disruptive behavior.[5–8] Moreover, their symptoms do little to raise community awareness of the disease. Thus, ADHD may be missed or its severity may be underestimated in girls, leading to fewer specialist referrals and underrepresentation in clinic-based studies.[9]

The atypical presentation of ADHD in girls may be a barrier to treatment, either because the condition is not recognized or because it is not seen as serious enough to warrant intervention. Paradoxically, when problematic behavior is identified in girls, the degree of deviation from the norm (compared with other girls) is thought to be much greater than it is for boys because girls are inherently less prone to inattention and hyperactivity than are boys.[7] Girls who are referred for psychiatric evaluation often show unusually disruptive behaviors, but they are probably not typical of most girls with ADHD.[8]

There is also evidence that ADHD takes a different type of toll on girls vs on boys. Although they do not differ from boys in measures of impulsivity, school performance, or social interactions, they have greater cognitive and attentional impairment[3] and may be rejected more often by their peers (particularly if they have the inattentive subtype).[7] Needing to repeat a grade in school is also more common among girls than among boys, which supports the observation that they experience more cognitive and academic problems.[10] In a study of adults, females with ADHD showed a higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and conduct disorder when compared with a control population, as well as cognitive impairments and academic problems.[6] The heavy social and personal impact of ADHD on females points to the importance of early identification and treatment.

Because ADHD is usually first suspected or recognized by a child's parents, teachers, and peers, the attitudes of people around these children can be important determinants of whether and how the child's condition is treated. In order to clarify perceived differences between girls and boys in the incidence and presentation of ADHD and in how ADHD is perceived by those around them, a large-scale survey was conducted. This survey examines gender variations in the disorder and explores how having ADHD is viewed by older children with ADHD, by their families and teachers, and by the general adult public.

Methods

Harris Interactive conducted a nationwide survey, drawing upon its Harris Poll Online Panel to identify potential respondents, who were then invited to participate in the survey via email. Each respondent was issued a unique password to guard against multiple responses from any participants. All interviews were conducted online. Respondents included samples of the general public (adults aged 18 years or older; n = 1797); parents of children with ADHD aged 6–17 years (n = 541); teachers who have taught a child with ADHD (n = 550), and children aged 12–17 years who had been diagnosed with ADHD (n = 346). The data for the general public, parents of children with ADHD, and teachers were weighted to be consistent with characteristics of those populations. The majority of respondents in all adult groups were white females and were generally evenly distributed with respect to age and household income. The demographics of all survey respondents are presented in Table 1A and Table 1B. Among participating children with ADHD, the boys and girls were well matched in terms of age, race, and region of residence.

Table 1A.

Demographics of Adult Survey Respondents

| General Public (%) n = 1797 | Parents (%) n = 541 | Teachers (%) n = 550 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 47 | 43 | 27 |

| Female | 53 | 57 | 73 |

| Age*(years) | |||

| 18–34 | 34 | 31 | 21 |

| 35–44 | 15 | 43 | 29 |

| 45–54 | 19 | 22 | 39 |

| 55 and over | 31 | 5 | 11 |

| Race† | |||

| White | 82 | 85 | 88 |

| Nonwhite | 12 | 12 | 7 |

| Household Income† | |||

| Less than $35,000 | 28 | 30 | 17 |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 13 | 17 | 19 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 17 | 22 | 30 |

| $75,000 or more | 24 | 19 | 21 |

| Region | |||

| East | 24 | 21 | 18 |

| Midwest | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| South | 30 | 36 | 38 |

| West | 23 | 19 | 21 |

*Percentages have been rounded off.

†Not all participants replied to this question.

Table 1B.

Demographics of Respondents With ADHD Aged 12–17 Years

| Boys (n = 253) | Girls (n = 93) | |

| Mean Age (years) | 14.4 | 14.6 |

| Race* (%) | ||

| White | 88 | 87 |

| Nonwhite | 9 | 10 |

| Region (%) | ||

| East | 21 | 26 |

| Midwest | 30 | 26 |

| South | 29 | 30 |

| West | 20 | 18 |

| Current Treatment(s) (%) | ||

| Medication | 64 | 60 |

| Behavior modification | 37 | 34 |

| No treatment | 19 | 28 |

*Not all children replied to this question.

A proprietary Web-based technology that enables large numbers of respondents to simultaneously complete the survey was used. Additionally, adaptations of advanced interviewing techniques for use online allowed question sequences to be tailored to each respondent during the course of the interviews. All Harris Interactive surveys are designed to comply with the code and standards of the Council of American Survey Organizations (CASRO) and the code of the National Council of Public Polls.

Results

A majority of the general public (58%) and an overwhelming majority of teachers (82%) believe that ADHD is more common in boys than in girls. Nearly all other respondents in these 2 groups think that it is equally prevalent in boys and girls, while few believe it is more prevalent in girls than in boys. Among the general public, 93% replied that they know a male with ADHD while only 50% said they know a female with ADHD.

Perceptions About Diagnosis

Another commonly held belief is that ADHD is identified more often in boys than in girls and at an earlier age. For example, 92% of teachers believe that ADHD is diagnosed more frequently in boys than in girls. More than half of the general public (51%) and teachers (59%) think that girls are diagnosed at a later age than boys, although many others (41% and 32%, respectively) feel that boys and girls are diagnosed at about the same age. Among the general public, 64% of those who believe that girls are diagnosed at a later age think that a reason for this disparity is that girls are more likely to “suffer silently.” Other commonly cited reasons are that girls do not “act out” (49%) and girls are generally more obedient than boys (21%). Only 13% respond that they believe it is simply because ADHD does not occur as often in girls as it does in boys.

This finding is mirrored by the responses of teachers regarding missed diagnoses. Among teachers, 85% believe that girls are more likely than boys to remain undiagnosed; of these, 92% attribute it to girls not “acting out.” More than half of parents and the general public also think that missed diagnoses are more common in girls. Forty-two percent of teachers report having more difficulty recognizing ADHD symptoms in girls than in boys, but even more (56%) believe that it is equally difficult in boys and girls. The general public and teachers both believe that behavior problems and classroom disruptions are the most common manifestations of ADHD in boys, whereas academic problems, inattention, or feelings of depression are the most common indications in girls (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceptions of the General Public and Teachers of the Most Common Problems Seen in Girls vs Boys With ADHD

| Public | Teachers | |||

| Girls (%) | Boys (%) | Girls (%) | Boys (%) | |

| Disrupting class | 6 | 22 | 9 | 42 |

| Academic problems | 15 | 8 | 13 | 6 |

| Behavior problems | 26 | 51 | 18 | 36 |

| Failing to complete work | 8 | 4 | 15 | 5 |

| Difficulty making friends | 7 | 1 | 4 | <1 |

| Feeling depressed | 16 | 1 | 12 | 0 |

| Being inattentive in class | 19 | 11 | 29 | 10 |

| None of the above | 3 | 2 | 1 | <1 |

| N | 1797 | 1797 | 550 | 550 |

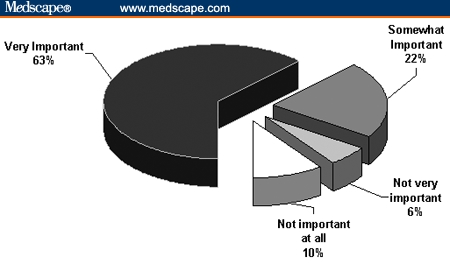

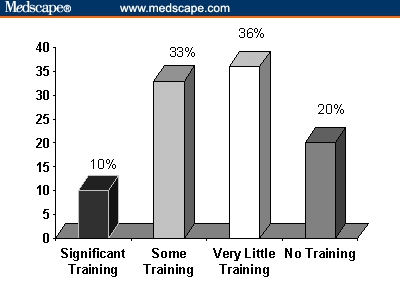

Among parents of children with ADHD, most believe that teachers play a “very important” role in helping children with ADHD (Figure 1). However, many teachers report that they have received little or no training in ADHD from their schools, while few report receiving significant training (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Most parents of children with ADHD believe that children's teachers play a crucial role in helping children with ADHD.

Figure 2.

Teachers' responses reveal that most schools provide little training to educate teachers about ADHD.

Teachers also observe that certain risky behaviors associated with ADHD show gender variations. For example, promiscuous behavior is believed by teachers to be more common among girls than boys (44% vs 28%, respectively), whereas driving too fast was seen as being more common in boys than in girls (26% vs 8%, respectively). However, when the children with ADHD were asked about their personal experience with the condition, few significant perceived differences between genders emerged. Girls were more likely than boys to report experiencing inappropriate talkativeness (73% vs 58%, respectively), difficulties with spelling (58% vs 43%, respectively), or feeling left out of activities with other children (46% vs 32%, respectively). In contrast to the teachers' expectations, there was no difference in the rate of self-reported speeding between the boys and girls who were old enough to drive.

Degree of Impairment

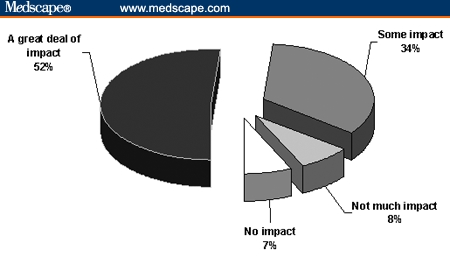

The burden of untreated ADHD may be experienced differently by boys and girls. The children taking medication for ADHD were asked to recall their lives before treatment. Although there are no significant differences reported between genders, girls are numerically more likely than boys to feel that it had been “very difficult” to get things done in general (57% vs 39%), to focus on schoolwork (77% vs 66%), to get along with parents (39% vs 26%), and to make friends (27% vs 18%). Most teachers believe that boys are just as likely as girls to have problems with their schoolwork and family relationships. Among parents, most (52%) feel that their children's ADHD has had a great deal of impact on their family life (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Most parents of children with ADHD indicate that ADHD can have a significant impact on family life.

Perceptions About Self-Esteem

Being diagnosed with ADHD can have complex effects on a child's self-image, and there may be real or perceived differences between boys and girls. For example, most teachers (72%) feel that children with ADHD have lower self-esteem than do other children, and more than half (56%) believe that girls are more likely to feel embarrassed about having ADHD than are boys. Approximately half of the parents state that ADHD affects a child's self-esteem “a great deal,” regardless of the child's gender. However, these concerns about self-esteem may be misplaced, according to the children themselves: among the subgroup who felt that something was wrong with them before being diagnosed, most girls report feeling better (53%) or about the same (32%) after learning they have ADHD. Among boys, most feel about the same (55%) or better (36%). Few boys or girls report feeling worse after being diagnosed with ADHD.

Similarly, 68% of the general public and teachers and 87% of parents worry that negative media coverage affects how children with ADHD feel. However, only 1 out of 3 children with ADHD (34%) report feeling embarrassed, angry, upset, or sad when they see media coverage of ADHD, and there are no significant differences between genders.

Perceptions About Mood

Teachers were split on the question of whether girls with ADHD are more likely than boys with ADHD (50%) or equally likely (47%) to display signs of depression. Girls currently taking an ADHD medication are numerically more likely than boys to report having previously tried a medication for depression (14% vs 5%), but the difference was not significant. Overall, 18% of parents report that their children with ADHD have also been diagnosed with depression, and 11% report that their children are currently taking medication for depression.

Perceptions About Medical Treatment for ADHD

Among the parents of children with ADHD, 73% state that their children are taking medication, 39% report counseling or behavior therapy, 6% mention other forms of treatment, and 22% state that their children are not currently receiving any treatment. Among the children with ADHD, 19% of the boys say they do not currently receive any treatment, compared with 28% of the girls.

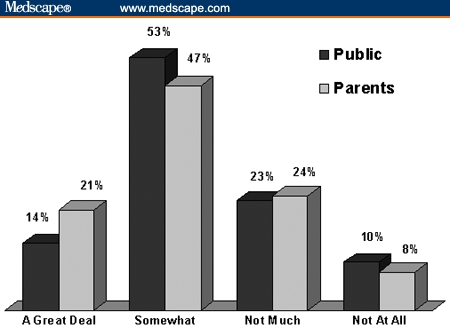

There are distinct differences between parents of boys and parents of girls in their attitudes about their children using ADHD medications (Table 3). Nearly all (92%) parents of girls with ADHD describe themselves as being “very willing” to seek medical advice when their child was first suspected of having ADHD. In contrast, only 73% of the parents of boys with ADHD recall being “very willing” to seek a medical opinion. One third of parents of boys with ADHD felt pressured to not put their children on medication for ADHD compared with one fifth of parents of girls with ADHD. Two thirds of parents of boys with ADHD who felt pressured not to put their child on medication confirm that they were pressured by family and friends, compared with only one third of the parents of girls with ADHD who had felt pressured. Similarly, 59% of parents of boys who were receiving ADHD medications say they were hesitant to use drug therapy compared with just 39% of the parents of girls receiving ADHD medications. However, the majority of the general public and the parents of children with ADHD believe that ADHD medications improve children's self-esteem at least “somewhat” (Figure 4).

Table 3.

Attitudes About Medical Evaluation and Treatment Among Parents of Boys and Girls With ADHD

| Factor | Parents of Boys (n = 421) | Parents of Girls (n = 120) |

| Willingness to seek medical advice for child suspected of having ADHD: | ||

| Very willing | 73% | 92% |

| Somewhat willing | 18% | 3% |

| Not very willing | 8% | 4% |

| Not willing at all | 2% | 1% |

| Parents of Boys Who Take ADHD Medication (n = 300) | Parents of Girls Who Take ADHD Medication (n = 96) | |

| Initially hesitant to put child on ADHD medication | 59% | 39% |

| Parents of Boys Who Felt Pressure to Not Put Their Sons on ADHD Medication (n = 135) | Parents of Girls Who Felt Pressure to Not Put Their Daughters on ADHD Medication (n = 23) | |

| Pressure to not put child on ADHD medication was attributed to: | ||

| Advice from family and friends | 67% | 31% |

| Stigma associated with ADHD medication | 59% | 47% |

Figure 4.

The majority of the general public and parents of children with ADHD believe that medication can improve the self-esteem of children with ADHD at least somewhat.

Discussion

Gender Differences in ADHD Recognition

The findings of this survey suggest that gender has important implications for the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. Among the most striking results is the belief that ADHD often goes unrecognized in girls, a viewpoint broadly held by the general public as well as those who are most familiar with the daily realities of the condition: the parents and teachers of affected children. It was also widely perceived that ADHD presents differently in girls from in boys, and that this is a likely reason for missed or delayed diagnoses in girls. Symptoms such as inattentiveness, poor school performance, and depressive affect are seen as the hallmark signs of ADHD in girls, yet they elicit less attention from teachers and parents than characteristic ADHD symptoms seen in boys, such as disruptive behavior and “acting out.” This is partly because girls' symptoms are not recognized as typical indications of ADHD and partly because these symptoms are less noticeable and less troublesome to adults than are boys' symptoms. The tendency of girls to “suffer silently” often means that they bear the burden of untreated ADHD for a much longer time than do boys.

Almost half of the teachers surveyed say that it is harder for them to recognize ADHD symptoms in girls than in boys, and most say they do not have adequate training about the disorder in general. They report that most schools provide little or no training on ADHD for teachers — in fact, only 10% of schools are reported to provide significant training for teachers to learn about ADHD. Even when teachers suspect a child may have ADHD, only half say they inform a child's parent or guardian. For girls with ADHD, this may be because the teachers are unsure of their opinion or because they are concerned that the girls will feel embarrassed or stigmatized by the diagnosis.

These survey responses are generally consistent with published reports. In the National Institutes of Health Consensus Statement on the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD, gender is acknowledged as a barrier to appropriate diagnosis.[11] While the boy-girl ratio of ADHD in population samples was 3:1, an equal gender distribution was found in a study of adult ADHD.[6] In another study of gender differences in a clinic-referred sample of ADHD in children, girls were generally older than boys at the time of their diagnoses.[10] These data suggest that ADHD in girls may be recognized at a later age than it is in boys. Lack of recognition of symptoms in girls has been attributed to the lack of gender-specific criteria for the diagnosis of ADHD and to the tendency of girls to be inattentive rather than impulsive or disruptive; thus, they can be overlooked by teachers and healthcare providers.[4,6,9] Members of the NIH Consensus Development Panel recommend additional studies of the inattentive subtype, particularly because it appears to be more common in girls.[11]

Gender Differences in ADHD Treatment

The failure to recognize ADHD symptoms in girls probably results in significant undertreatment. Although the subjective experience of ADHD is evidently different for girls and boys, it is not a trivial disorder for them, and they are equally in need of professional care. According to the teachers and the children with ADHD responding to this survey, girls are perceived to have at least as much difficulty with schoolwork, friends, and family as do boys. In this survey, there was a trend for girls to report more problems than did boys in these areas, but this may be partly because girls tend to be better at communicating their feelings; boys may well have similar problems but not be able to express them as well. Girls were also described as being likely to engage in promiscuous behavior, which would put them at risk of serious consequences such as unplanned pregnancies or sexually transmitted diseases.

Undertreatment may even be a problem for girls who are correctly diagnosed if their parents are hesitant about letting them use an ADHD medication. In this survey, parents whose children were currently using ADHD medication recalled that at first, they felt pressured not to agree to it, partly due to concerns about side effects and partly due to worries about the stigma associated with ADHD or its treatment. However, the survey suggests that children may feel less stigmatized by ADHD than their parents fear: only 9% of boys and 15% of girls report that they felt worse after being diagnosed with the condition; the remainder felt “about the same” or “better.” Similarly, most parents and teachers believe that negative media coverage of ADHD hurts affected children, yet the vast majority of children with ADHD report no negative emotions when seeing the condition portrayed in the media.

Girls may be at a slight advantage over boys in one sense: once they are suspected of having ADHD, their parents tend to be more willing to seek medical advice and less likely to feel pressure not to use drug therapy. Of the parents whose children were currently taking an ADHD medication, 59% of the parents of boys say they were hesitant to put their child on that drug, compared with only 39% of parents of girls. Although the reasons for this disparity are unknown, one possible reason is that ADHD is most often diagnosed in girls when it is severe, so parents are more willing to seek professional help. Another possible reason is that the restlessness and impulsivity of boys with ADHD is seen as being within the spectrum of normal or near-normal behavior for boys, so their parents do not accept it as a medical problem that could require drug treatment. In general, boys and girls respond equally well to medical therapy for ADHD.[12,13]

The limitations of this study lie in possible selection biases in the sample of respondents. Because the survey was Web-based, respondents had to own a computer and have good literacy and computer skills. Thus, the study sample could be biased toward participants with better education or a higher socioeconomic status than those of the general population. Also, children who are young or have severe impairments in attention or conduct are unlikely to complete a lengthy online questionnaire; therefore, the children answering the survey are likely to be older and have less severe symptoms than children with ADHD in general.

Conclusions

The general public and adults who are familiar with ADHD agree that the condition is often difficult to recognize in girls and therefore more likely to be undertreated. Overcoming these problems will require education to increase general awareness of the disorder in females and to equip teachers, parents, and healthcare professionals with the tools to recognize specific symptoms. Fortunately, as the diagnostic criteria for ADHD have evolved over the years, more girls' symptoms are now being recognized and more girls are being appropriately treated.[14,15]

More research is needed to characterize the gender differences in ADHD presentation, course, and comorbidities, particularly mood disorders. To date, there have been no prospective studies solely in female patients with ADHD, although one such trial is currently under way. This survey offers several clues that ADHD may be linked with depression in girls: the general public and teachers observed signs of depression more often in girls than in boys; several of the girls taking ADHD medication report that they had been treated previously with an antidepressant; and the majority of parents recognized signs of depression in their daughters with ADHD. However, much remains to be learned about the apparent association between ADHD and depression: ADHD may indeed coexist with depression or it may simply be misdiagnosed as depression due to overlapping symptom profiles.

The fact that most adults are aware of the underdiagnosis of ADHD in girls is encouraging because it suggests that they will be receptive to learning more about the disorder. With broader awareness of ADHD and better understanding of gender differences in its presentation, girls should no longer have to “suffer silently” with the many social and educational burdens of the disorder.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Quinn would like to acknowledge the Harris ADHD Working Group, Dr. Timothy Wilens, Dr. Thomas Spencer for their contributions to this article.

Footnotes

This survey was supported by funding from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Contributor Information

Patricia Quinn, Director, National Center for Gender Issues and ADHD, Silver Spring, Maryland. Email: pquinn@ncgiadd.org.

Sharon Wigal, University of California, Irvine.

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and evaluation of the child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2000; 105: 1158-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gaub M, Carlson CL. Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolsc Psychiatry. 1997; 36: 1036-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lahey BB, Applegate B, McBurnett K, et al. DSM-IV field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1994; 151: 1673-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, et al. Influence of gender on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children referred to a psychiatric clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159: 36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens T, Mick E, Lapey KA. Gender differences in a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1994; 53: 13-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arnold LE. Sex differences in ADHD: conference summary. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996; 24: 555-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gershon J. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD. J Attention Dis. 2002; 5: 143-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hinshaw SP. Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Background characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive and social functioning, and parenting practices. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002; 70: 1086-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown RT, Madan-Swain A, Baldwin K. Gender differences in a clinic-referred sample of attention-deficit-disordered children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1991; 22: 111-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. NIH Consensus Statement. Diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). 1998;16:1-37. Available at http://consensus.nih.gov/cons/110/110_intro.htm. Accessed April 5, 2004. [PubMed]

- 12. Barkley RA. Hyperactive girls and boys: stimulant drug effects on mother-child interactions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1989; 30: 379-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pelham WE, Walker JL, Sturges J, Hoza J. Comparative effects of methylphenidate on ADD girls and ADD boys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989; 28: 773-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goldman LS, Genel M, Bezman RJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. JAMA. 1998; 279: 1100-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robison LM, Skaer TL, Sclar DA, Galin RS. Is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder increasing among girls in the US? Trends in diagnosis and the prescribing of stimulants. CNS Drugs. 2002; 16: 129-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]