Abstract

Context

Antimicrobial resistance is a serious public health concern worldwide. Inappropriate prescribing, including the wrong drug, incorrect dose/duration, and poor compliance, contributes to it.

Objective

To identify factors determining the attitudes and practices of prescribers regarding antibiotic usage and to suggest measures that contain antibiotic resistance.

Design and Setting

With a convenient sample, general practitioners and specialists of both sexes from 5 districts of Tamilnadu state, India, were approached for the study. A slightly modified, self-administered, anonymous questionnaire of the Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics was used. The deciding factors to prescribe an antibiotic and the reasons for the attitude to prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic were elicited.

Results

Out of the 285 participants 120, 110, and 47 practiced at city, semiurban, and rural areas, respectively. The responses were graded with a total possible score of 150. There was no significant difference between men and women or between specialist and nonspecialists in scores. The majority believed that antibiotics are overprescribed. Purulent discharge (65%), antibiotic-resistance concerns (48%), fever (40%), and patient satisfaction (29%) were the strong influences to prescribe an antibiotic. Similar reasons were cited for the belief of prescribing a broad-spectrum antibiotic. The 3 most commonly prescribed antimicrobials were amoxicillin (21%), ciprofloxacin (18%), and co-trimoxazole (11%). About 42% used an antibiogram only to the extent of less than 10%.

Conclusion

Patient requests/expectations, patient satisfaction, purulent discharge, and fever strongly pressurized practitioners to prescribe antibiotics. Patient and time pressures, diagnostic and treatment uncertainties, and the poor utilization and/or ill-affordable antibiogram facility all point to an urgent, multidimensional approach to contain antibiotic resistance.

Introduction

Wider and more prevalent usage of antibiotics is not only a concern for the community or to certain nations but all over the world. As a result of this wide usage, the people are at a high risk of antibiotic resistance. The problem of multidrug resistance in recent times because of unregulated sale and self-medication has created a great public health concern.[1] As has been rightly pointed, “Antimicrobial resistance is a risk that threatens to turn back the clock to a darker age in the industrialized countries and to block health progress in the developing world.”[2] The problem of antimicrobial resistance has snowballed to a serious public health concern with economic, social, and political implications worldwide. The rate of drug-resistant bacteria is dramatically increasing.[3] Our challenge is to slow the rate at which resistance develops and spreads.[4]

Containment of antimicrobial resistance, although not easy, is not impossible. The importance of the judicious use of antibiotics in limiting the spread of antibiotic resistance[5] cannot be overemphasized because this strategy minimizes any unnecessary, inappropriate, or irrational use of antimicrobials. Among the core groups, the major potential players with a leading role in the above strategy are prescribers. Inappropriate prescribing practices, including the wrong choice of drug, the incorrect dosage or duration of treatment, poor compliance, and the use of poor-quality drugs, all contribute to antimicrobial resistance.[6] Only by understanding the reasons underlying inappropriate prescribing can one define effective interventions.[7]

Hence, the present study was aimed at identifying prevalent practices and attitudes of prescribers, especially private-sector medical practitioners in city, semiurban, and rural regions of Tamilnadu (a southern state of India).

Subjects and Methods

The survey was carried out with a self-administered, anonymous questionnaire encompassing the factors influencing their decision making and attitude toward antibiotic-prescribing practices. The participants included nonspecialists (general practitioners holding an MBBS degree) and specialists (medical, surgical, obstetrics/gynecology, pediatrics etc holding postgraduate degrees/diplomas in the respective field). The survey was carried out in 5 districts of the state of Tamilnadu, India (4 metropolitan cities, 2 towns (semiurban), and the satellite rural areas adjoining the above cities). The whole state is covered by about 50,000 registered medical practitioners. The study was conducted from May to June 2003. The sampling of the participants was a convenient one, determined by the proximity of the practitioners to the authors. The authors approached the participants individually and requested them to fill out the questionnaire. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee.

The questionnaire used was the slightly modified version of that used by the Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics in cooperation with the Massachusetts Infectious Disease Society and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.[8]

Briefly, the items in the questionnaire consisted of the basic details (age, sex, educational status, and practice place), questions pertaining to the factors involved in the decision making to prescribe an antibiotic in an outpatient setting (like fever, purulent discharge, patient request, etc), and factors responsible for the attitude to prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic in which a narrow spectrum would suffice (Figures 1 and 2). Apart from that, the 3 most common infectious diseases the practitioners often treat, the 3 most common antibiotics they prescribe, and the extent to which they use the antibiogram facility were also elicited. Finally, they were asked to express their opinions on ways and means to use antibiotics prudently. The language of the questionnaire was English, and the time taken for filling it out was about 10 minutes. All the data were entered in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and rechecked by 2 independent persons for any errors.

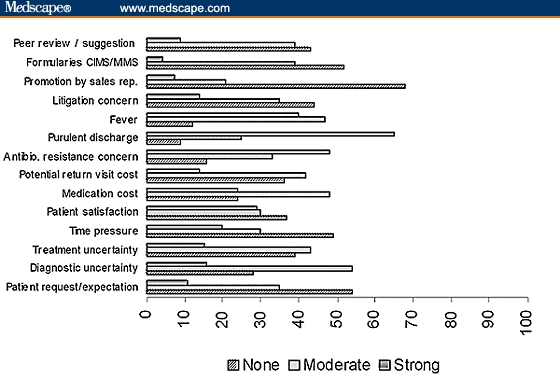

Figure 1.

Percentage of practitioners stating the factors that influence their decisions to prescribe an antibiotic in an outpatient setting.

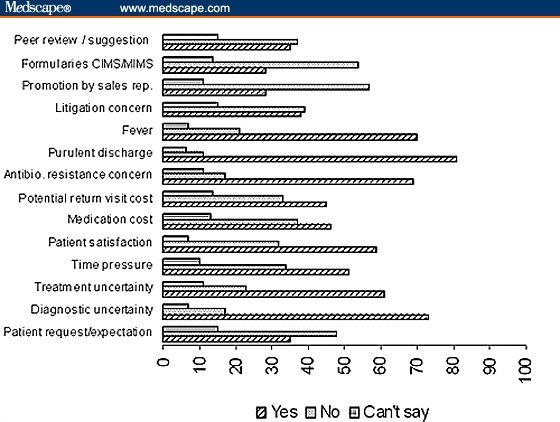

Figure 2.

Percentage of practitioners stating the reasons for prescribing a broad-spectrum antibiotic when a narrow-spectrum antibiotic would suffice.

Results

The results were expressed as descriptive statistics, and the difference between groups was subjected to a Chi square test where applicable. A total of 380 practitioners were approached of whom only 285 agreed to participate (with a response rate of 75%). The age of the participants ranged from 23 to 71 years (median, 37.5 years) for men (total, 181) and 24–68 (median, 38 years) for women (total, 104). Among the participants 120, 110, and 47 practiced at city, semiurban, and rural areas, respectively (8 participants' data were blank in this aspect). The breakups of other demographic details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Demographic Details of the Participants of the Antibiotic Survey

| Educational Status | Male | Female | Total | |||

| Number | %* | Number | % | Number | %* | |

| MBBS | 68 | 23.9 | 44 | 15.4 | 112 | 39.3 |

| MD (General Medicine) | 53 | 18.6 | 14 | 4.9 | 67 | 23.5 |

| MS (General Surgery) | 3 | 1.1 | 18 | 6.3 | 21 | 7.4 |

| MD/DGO (Obstetrics & Gynecology) | 2 | 0.7 | 24 | 8.4 | 26 | 9.1 |

| MD/DCH (Pediatrics) | 14 | 4.9 | 10 | 3.5 | 24 | 8.4 |

| Other specialties | 26 | 9.1 | 9 | 3.2 | 35 | 12.3 |

| Total | 181 | 63.5 | 104 | 36.5 | 285 | 100 |

| Practice place | ||||||

| City | 78 | 27.4 | 42 | 14.7 | 120 | 42.1 |

| Semiurban | 68 | 23.9 | 42 | 14.7 | 110 | 38.6 |

| Rural | 27 | 9.5 | 20 | 7.0 | 47 | 16.5 |

*Percentages are rounded off to the nearest digit.

A comprehensive scoring system was used with a total possible score of 150 by each participant. The details of points awarded were as follows: for each factor that influenced the physician to prescribe an antibiotic (none = 5, moderate = 3, and strong =1) and for each question on the attitude why physicians prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic when a narrow-spectrum antibiotic would suffice (no = 5, can't say = 3 and yes = 1).

A score between 106 and 150 (ie, > 70%) indicated that a participant has both good practicing principles and a positive attitude regarding antibiotic use and resistance, whereas that between 62 and 105 (41% to 69%) was considered as average and 60 and less (< 40%) as poor. Only 12% of the participants' score was good, whereas 76% scored average. The score details are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Score Range of Participants Based on Their Responses to Questions Pertaining to Antibiotic Practice and Attitude to Prescribe an Antibiotic

| Category | Poor < 61 | Average 62–105 | High 106–150 | |||

| Number | %* | Number | % | Number | %* | |

| Male | 20 | 7 | 133 | 47 | 25 | 9 |

| Female | 10 | 4 | 82 | 29 | 9 | 3 |

| Total | 30 | 11 | 215 | 76 | 34 | 12 |

| Specialist | 17 | 6 | 133 | 47 | 22 | 8 |

| Nonspecialist | 13 | 5 | 82 | 29 | 12 | 4 |

| Total | 30 | 11 | 215 | 76 | 34 | 12 |

*Percentages are rounded off to the nearest digit.

Sixty percent of the respondents believed that antibiotics are overprescribed by physicians. There was no significant difference between the men and women practitioners or between specialists and nonspecialists regarding the scores. A comparison between the geographic areas was not done because of the small number of rural practitioners.

In the order of decreasing importance, the participants cited that purulent discharge (65%), antibiotic-resistance concerns (48%), fever (40%), and patient satisfaction (29%) are the first 4 strong influences for prescribing an antibiotic in an outpatient setting. Further, medication cost & potential return-visit cost as well as treatment & diagnostic uncertainty indicated moderate-to-strong reasons for prescribing an antibiotic in more than 50% of the participants (Figure 1). The percentage of blanks (no response) ranged from 0.4 to 8.8 for various items.

The first 4 important reasons stated for the attitude to prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic (when a narrow-spectrum antibiotic would suffice) were purulent discharge, diagnostic uncertainty, fever, and antibiotic-resistance concerns.

More than 50% believed that patient satisfaction, time pressure, and treatment uncertainty were the reasons for prescribing a broad-spectrum antibiotic (Figure 2). The percentage of blanks (no response) ranged from 2 to 13 for various items.

The 3 most common infectious diseases treated in private practice were lower-respiratory-tract infections (21.5%), urinary-tract infections (14%), and diarrhea (13.2%). The 3 most commonly prescribed antimicrobials were amoxicillin (20.5%), ciprofloxacin (17.6%), and co-trimoxazole (10.5%). However, when analyzed in broad terms (as groups) aminopenicillins (26.5%), quinolones (24.9%), and cephalosporins (14.6%) topped the list. About 42% of the practitioners requested for culture and sensitivity (C&S) to the extent of only less than 10%, and barely 10% of practitioners asked the same in > 50% of their cases.

Regarding the opinion expressed for what would help to promote more prudent usage of antibiotics, the following were offered (Table 3): proper investigations and diagnosis (19%), antibiotics knowledge and awareness (16%), judicious antibiotic use (13%), the necessity for guidelines, continuing medical education (12%), and the availability of a cheap, rapid C&S facility (9%).

Table 3.

Responses of the Physicians on the Question “What Would Help to Promote More Prudent Use of Antibiotics?”

| Suggestions* | Number | % |

| Proper investigations and diagnosis | 61 | 19.1 |

| Improve antibiotics knowledge and awareness | 51 | 16.0 |

| Judicious antibiotic use | 42 | 13.2 |

| Guidelines, continuing medical education | 39 | 12.2 |

| Cheap, rapid culture and sensitivity facility | 30 | 9.4 |

| Patient awareness | 20 | 6.3 |

| Clinical evidence | 7 | 2.2 |

| Restrict over-the-counter sale of antibiotics | 7 | 2.2 |

| Supervision by governing bodies | 4 | 1.2 |

| Effective and cheap antibiotics | 2 | 0.6 |

| Ban commissions, protected water supply, crack down quacks, ensure complete cure, use only generic name, population-resistance pattern | 1 each (6) | 1.9 |

| No suggestions | 50 | 15.7 |

| Total | 319* | 100 |

*There was more than 1 suggestion by some.

Discussion

It is clear from the participants' own admission that there is an overuse of antibiotics.

The following are factors that influence physician prescribing.

Patient Pressure

As has been the case in other studies,[9,10] patients appear to exert tremendous pressure on the physicians' prescribing habits. Because of patient requests/expectations, 35% of the physicians felt moderate and 11% a strong pressure to prescribe antibiotics. Similarly, to assure patient satisfaction, 30% of the physicians felt moderate and 29% a strong pressure to prescribe antibiotics. Zaidi and colleagues [11] have recently highlighted the woes of antibiotic misuse in developing countries (Southeast Asia) and have suggested “patient education” especially involving the female population as one of the many measures for containment of antibiotic resistance. The need for patient education is probably more acute in developing countries at least to relieve the pressures of the practitioners serving at all odds (self medication, expectations of quick relief, over-the-counter availability of antibiotics, etc).

Treatment or Diagnosis

When encountered with purulent discharge or fever, 25% and 47% of practitioners, respectively, felt moderate pressure, whereas 65% and 40% felt strong pressure to prescribe antibiotics, respectively. Additionally, when the diagnosis or treatment was uncertain, 54% and 43% of practitioners felt at least moderate pressure to prescribe antibiotics, respectively. Similar to other reports, respiratory-tract infections accounted for the majority of the antibiotic usage,[12] and ampicillin happened to be the top drug prescribed[13] despite the fact that a majority of respiratory infections are of viral etiology. Thankfully, neither promotion by the pharmaceutical companies nor the formularies do have a major pressurizing influence.

The reasons for the attitude to prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic when a narrow-spectrum antibiotic would suffice are as follows.

About 73% believed that diagnostic uncertainty was the reason why physicians often prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic when a narrow-spectrum antibiotic would suffice. This probably mostly happens in cases of fever (70%) and purulent discharge (81%).

The probable reasons may be many, such as cost, time pressure, and lack of facilities for a rational approach (involving an antibiogram). The fact that sizable respondents cited that a culture and sensitivity facility was not available at a reasonable cost is logical. The other equally important reasons may be lack of antibiotic guidelines, regional laboratories with periodic information over antibiotic resistance, etc. This is reflected by the response of the physicians for treatment uncertainty (61%) and their suggestions to involve C&S tests. The fear of resistance development alone probably drives people to prescribe a broad-spectrum antibiotic in the first instance itself (when a narrow-spectrum antibiotic would have sufficed).

The major stumbling block for the practitioners, according to the present study, is nonavailability of a rapid, low-cost, local laboratory facility for an antibiogram. Steps in this direction alone may improve the current scenario to a great extent. Additionally, practitioners should be offered periodic training and education to keep them updated on antibiotics, guidelines, and resistance patterns, as suggested by many of the participants.

The shortcomings of the present study include the following: First, the sampling of the participants was not randomized; hence, a true representation of the population could not be claimed. Second, the questionnaire used was not a validated one but a slightly modified version of an earlier study carried out in a developed country; however, there were many similarities in the results (including the “antibiotic resistance concerns” factor). Third, the scoring system used in the present study is our own idea and it is an arbitrary one, which may or may not reflect the true picture of what it is intended for.

Despite these shortcomings, it is evident that the majority of the practitioners admit that antibiotics are overused. Further, the patient and time pressures, diagnostic and treatment uncertainties, and the poor utilization of even the meager resources (an antibiogram facility) all point to an urgent, multidimensional approach to contain any potential antibiotic resistance of greater magnitude.

The global increase in resistance to antimicrobials has created a public health problem of potentially crisis proportions. The development of resistant microbes will remain as a problem whenever antimicrobials are used. The misuse and overuse of antimicrobials have exacerbated the problem by adding selection pressures that favor resistance. This includes inappropriate prescribing by physicians,[14] poor compliance by patients,[15] and the over-the-counter availability of antimicrobials as a nonprescription commodity in many developing countries. Resistance development is a natural, unstoppable process exacerbated by the abuse, overuse, and misuse of antimicrobials. Our challenge is to slow the rate at which resistance develops and spreads.[4]

Containment of antimicrobial resistance calls for a concerted approach from the individual to the global level involving the World Health Organization (WHO) (for effective surveillance and to promote the formulation of national antibiotic guidelines), which it already undertakes, drug industries (the development of new antimicrobials and vaccines and making available the materials at a cheaper cost for an antibiogram), national governments (for effective control over the misuse of antimicrobials, setting up of nodal and regional surveillance laboratories, and the dissemination of contemporary data on resistance patterns), nongovernmental organizations (consumer education and public awareness about the appropriate use of antimicrobials and the problem of resistance), and medical educators (improved training in medical colleges of the would-be practitioners and continuing medical education to physicians already in practice). The various arms of the concerted approach are akin to the spokes of an umbrella, and malfunctioning or nonfunctioning of 1 or more may defeat the very purpose of the (antibiotic) umbrella.

Conclusion

Purulent discharge, antibiotic-resistance concern, fever, and patient satisfaction were some of the strong factors influencing the prescribers to prescribe an antibiotic according to the present study. Although physicians often blame patients for demanding antibiotics, physicians, by their own admission, may prescribe more antibiotics because of treatment or diagnosis uncertainty.

The present reality, to prescribe an antibiotic as the “iron will” and fever as the “gold standard,” should change for the better or else the arms of “antibiotic resistance” will continue to grow exponentially. Then the pressure of the hug on the community would be enormous. The need of the hour is an attitudinal change that “not every bug needs a drug” or else the logical sequences would be a decline in effectiveness to existing antimicrobials, difficult treatment options, and inefficient epidemics control.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their special appreciation to Dr. C. Jayashree as well as Ms. Uma, Priya, Latha, and Saraswathy for their valuable help. The authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for selecting A. Anusha Raaj, II MBBS, as a student researcher in the above project. The support offered by the deans of the respective institutions is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank all the practitioners who participated in the study. A special thanks goes to Dr. Anibal Sosa, Director, Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics (APUA), Boston, Massachusetts, for the suggestions and permission to use their questionnaire.

Contributor Information

P Thirumalaikolundusubramanian, Professor of Medicine, Madurai Medical College, Madurai, Tamilnadu, India.

A Anusha Raaj, II Year MBBS Student, Chengalpattu Medical College, Chengalpattu, Tamilnadu, India.

K Namasivayam, Tutor in Medicine, K A P Viswanatham Government Medical College, Tiruchirappalli, Tamilnadu, India.

S Rajaram, Professor of Pharmacology, Vinayaka Mission Kirupanandha Variyar Medical College, Salem, Tamilnadu, India.

References

- 1. Montefiore DG, Osoba AO. Antibiotic use in Nigeria. Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotic Newsletter. 1985; 3: 1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Editorial -- antimicrobial resistance: a global threat. Essent Drugs Monit. 2000; 28&29: 1. Available at: http://www.who.int/medicines/library/monitor/EDM2829en.pdf Accessed April 26, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Butler JC, Hofmann J, Cetron MS, Elliott JA, Facklam RR, Breiman RF. The continued emergence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pneumococcal Sentinel Surveillance System. J Infect Dis. 1996; 174: 986-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization Report on Infectious Diseases 2000. Overcoming Microbial Resistance. Available at: http://www.who.int/infectious-disease-report/2000/ Accessed April 29, 2004.

- 5. Maskalyk J. Antimicrobial resistance takes another step forward. CMAJ. 2002; 167: 375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams R. Antimicrobial resistance: the facts. Essent Drugs Monit. 2000; 28&29: 7. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holloway K. Who contributes to misuse of antimicrobials? Essent Drugs Monit. 2000; 28&29: 9. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Massachusetts Physician Survey -- Pilot Survey of Primary Care Physicians in Massachusetts. 1998 Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics; 1999. Available at: http://www.tufts.edu/med/apua/Research/physicianSurvey1-01/physicianSurvey.htm Accessed April 29, 2004.

- 9. Nathwani D, Davey P. Antibiotic-prescribing -- are there lessons for physicians? Q J Med. 1999; 92: 287-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Handysides S. Antibiotic resistance and prescribing for self limiting diseases -- the battle goes on. Eurosurveillance Weekly. 1997; 1: 970925. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zaidi AKM, Awasthi S, Janaka deSilva H. Burden of infectious diseases in South Asia. Br Med J. 2004; 328: 811-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alberta Management Committee on Drug Utilization. Anti-Infective Guideline Adherence in Alberta -- A Drug Utilization Review. Alberta Drug Utilization Review. 2003; 4. Available at: http://www.ccar-ccra.com/wordfiles/Alberta-Drug-Use-Review.doc Accessed April 26, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13. McManus P, Hammond ML, Whicker SD, Primrose JG, Mant A, Fairall SR. Antibiotic use in the Australian community, 1990-1995. Med J Aust. 1997; 167: 124-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. PAHO Director, in Beijing, Calls for Global Responses to Global Health Challenges. Pan American Health Organization 2000. Resistencia Bacteriana en las Americas. Revista Panamericana de Infectologia. 1999. (3). Available at: http://www.paho.org/English/DPI/PRESS_000902.HTM Accessed April 26, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bojalil R, Calva JJ. Antibiotic misuse in diarrhea. A household survey in a Mexican community. [abstract]. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994; 47: 147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]