Abstract

The integrase from the Streptomyces phage φC31 is a member of the serine recombinase family of site-specific recombinases and is fundamentally different from that of λ or its relatives. Moreover, φC31 int/attP is used widely as an essential component of integration vectors (such as pSET152) employed in the genetic analysis of Streptomyces species. φC31 or integrating plasmids containing int/attP have been shown previously to integrate at a locus, attB, in the chromosome. The DNA sequences of the attB sites of various Streptomyces species revealed nonconserved positions. In particular, the crossover site was narrowed to the sequence 5′TT present in both attP and attB. Strains of Streptomyces coelicolor and S. lividans were constructed with a deletion of the attB site (ΔattB), and pSET152 was introduced into these strains by conjugation. Thus, secondary or pseudo-attB sites were identified by Southern blotting and after rescue of plasmids containing DNA flanking the insertion sites from the chromosome. The sequences of the integration sites had similarity to those of attB. Analysis of the insertions of pSET152 into both attB+ and ΔattB strains indicated that this plasmid can integrate at several loci via independent recombination events within a transconjugant.

Streptomyces bacteria are gram-positive organisms that produce pharmacologically important secondary metabolites and undergo a complex life cycle (6, 10). Streptomyces coelicolor A3 (2) is genetically the best studied Streptomyces species, and the sequence of the 8,667,507-bp linear chromosome of this organism has recently been determined at the Sanger Centre (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor/) (2). Many species in the genus are amenable to genetic manipulation, and some of the most widely used vectors are derived from the site-specific recombination system of the Streptomyces temperate phage φC31 (12).

The φC31 integrase is fundamentally different from the recombinases of the λ integrase family (17, 22, 23). It is a member of the serine recombinases and as such is thought to use a mechanism of recombination similar to that used by the well-studied resolvase-invertase family (7, 19). Resolvases, such as those encoded by Tn3 or γδ, recognize the recombination sites, or res sites, and bring the DNA together to form a synapse. The recombinases then cleave all four strands in a concerted fashion to form a staggered break at a 2-bp sequence, and transient phospho-serine linkages are formed to the recessed 5′ ends. The substrates are then positioned in the recombinant format, and the phosphodiester backbone is rejoined. The pairs of sites that are acted on by φC31 integrase and other serine integrases are nonidentical (17). Thus, like λ integrases, φC31 integrase acts on an attB site and an attP site to form attL and attR. However, unlike those of λ integrases, the sites are both very small, with attP and attB being just 39 and 34 bp in size, respectively (8). Also, φC31 integrase does not require an accessory factor for integration, and this reaction proceeds in vitro in the presence of buffer, purified integrase, and the substrates containing attP and attB (22). Moreover, the integrase reaction appears to be irreversible in the absence of any other factors; i.e., the integrative reaction has been observed only in vitro or in heterologous hosts, and nonpermissive pairs of sites such as attP/attP, attB/attL, etc., do not recombine (21, 22). In nature, however, the excisive reaction between attL and attR must occur and this probably requires a phage-encoded accessory factor such as Xis. Indeed an Xis has been identified for the homologous serine integrase encoded by the lactococcal phage TP901-1 (4).

There must be features of the attB and attP sites that are responsible for recognition by integrase. Here we have studied the natural variation in attB sites among various Streptomyces species and investigated the nature of secondary or pseudo-attB sites in S. coelicolor and S. lividans. Three pseudo-attB sites were identified in strains with a deletion of the attB site (ΔattB), all with sequences reminiscent of attB. Analysis of the insertions of pSET152 into both attB+ and ΔattB strains indicated that this plasmid can integrate at several loci via independent recombination events within a transconjugant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Streptomyces and Escherichia coli strains were as described in Table 1. Streptomyces cultures were maintained on soy-mannitol agar or R2YE medium, and mycelia were prepared for genomic DNA preparations by growth in yeast extract-malt extract medium for 36 h at 29°C. E. coli was grown on yeast-tryptone agar or yeast-tryptone broth at 37°C. Conjugations of plasmids from E. coli to Streptomyces were performed as described by Kieser et al. (12). After isolation of transconjugants, single colonies were crushed in sterile water and spread on soy-mannitol agar containing nalidixic acid and apramycin and the spores were harvested. This spore stock was then used as an inoculum to prepare genomic DNA.

TABLE 1.

Bacteria, plasmids, and oligonucleotides

| Bacterial strain (name or no.) or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. coelicolor A3(2) | ||

| J1929 | ΔpglY | 1 |

| PCS41 | ΔpglY ΔattB | This work |

| PCS412 | ΔpglY ΔattB (pSET152) | This work |

| PCS418 | ΔpglY ΔattB (pSET152) | This work |

| PCS4110 | ΔpglY ΔattB (pSET152) | This work |

| S. lividans 66 | ||

| TK24 | Strr | 12 |

| PCS13 | Strr ΔattB | This work |

| PCS131 | Strr ΔattB (pSET152) | This work |

| PCS135 | Strr ΔattB (pSET152) | This work |

| PCS139 | Strr ΔattB (pSET152) | This work |

| S. hygroscopicus NRRL5491 | P. Leadlay | |

| S. longisporoflavus 83E6 | P. Leadlay | |

| S. aureofaciens | I. S. Hunter | |

| S. cinnamonensis | I. S. Hunter | |

| S. clavuligerus | S. Baumberg | |

| S. griseus ATCC 12475 | S. Baumberg | |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recAl endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 16 |

| ET12567 (pUZ8002) | dam, dcm, hsdM Cmr Kanr | 12 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSET152 | φC31-derived integration vector, Aprar | 3 |

| pSET151 | Suicide vector, Thior | 3 |

| pGEM7 | Cloning vector | Promega |

| pPC30 | pGEM7 containing 4,115-bp SphI-BamHI fragment from cosmid AC2 | This work |

| pPC33 | ΔattB, pPC30 derivative | This work |

| pPC34 | 4,024-bp SphI-BamHI fragment from pPC33 inserted into pSET151 | This work |

| pPC4121, pPC4122 | Plasmids rescued from PCS412 | This work |

| pPC4184 | Plasmid rescued from PCS418 | This work |

| pPC41104 | Plasmid rescued from PCS4110 | This work |

| pPC1311-pPC1316 | Plasmids rescued from PCS131 | This work |

| pPC1391, pPC1392, pPC1396 | Plasmids rescued from PCS139 | This work |

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Genomic DNA from Streptomyces strains was prepared according to a previously described method (12). PCRs were performed as described previously (16), using Red Hot Taq (ABgene) or Expand (Roche). PCRs to test for the presence or absence of the ΔattB gene were set up, using material taken directly from patches of S. lividans or S. coelicolor derivatives growing on an agar plate to provide the template. The initial heat denaturation step (10 min, 95°C) was sufficient to lyse the material and release the DNA template. Plasmid DNAs were prepared, using mini-prep (Qiagen) kits or a midi-prep (Sigma) kit, from E. coli cultures grown overnight which contained the appropriate antibiotic. DNA manipulations with restriction endonucleases, DNA polymerase (Klenow fragment), and T4 DNA ligase were performed according to the manufacturers' instructions (Life Technologies and New England Biolabs). Agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting were performed as described previously (16). DNA fragments and PCR products were purified using a kit (Qiagen). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Biopolymer Synthesis and Analysis Unit of the University of Nottingham. DNA sequencing was also carried out by the Biopolymer Synthesis and Analysis Unit, using an ABI 377 DNA sequencer.

RESULTS

Diversity of φC31 attB sites from different Streptomyces species.

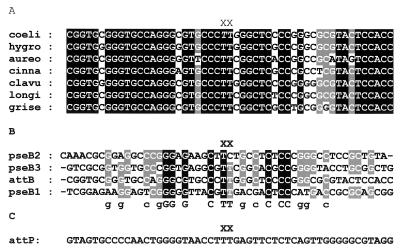

The attB site lies within an open reading frame (ORF) coding for a putative chromosome condensation protein, SCAC2.06c, with homology to a mammalian encoded protein, pirin (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor). The conservation that exists between pirin homologues in other microbes, plants, and animals was exploited in the design of primers used to amplify the DNA by PCR containing attB from several Streptomyces species. Two primers, ATTB1 and ATTB2, were synthesized that corresponded to the DNA encoding two very highly conserved regions of SCAC2.06c. Where necessary, degeneracies were introduced in positions that corresponded to the third position of the codons. Fragments containing attB were obtained by PCR from S. coelicolor, S. aureofaciens, S. hygroscopicus, S. cinnamonensis, S. longisporoflavus, S. griseus, and S. clavuligerus and sequenced (Fig. 1). Two of these species (S. coelicolor and S. hygroscopicus) are known to form stable φC31 lysogens (14, 15), and φC31-derived integrating plasmids have been successfully used with S. aureofaciens and S. clavuligerus (20, 25), implying that these four species have a functional attB site. An alignment of the attB sequences indicated positions in the minimal site that can tolerate base changes (Fig. 1). A comparison of the S. ambofaciens attB sites with attP had previously indicated that the core sequence (i.e., the region at which the crossover occurs) was 5′TTG (13). The core sequence can now be shortened to 5′TT, as the attB sequences from S. aureofaciens, S. cinnamonensis, S. longisporoflavus, and S. griseus all contained 5′TTC (Fig. 1). To confirm that the attB sites containing 5′TTC were active in recombination, the DNA fragments from S. cinnamonensis, S. griseus, and S. longisporoflavus that encode attB were inserted into the cloning vector pGEM7 and used in in vivo recombination assays with E. coli containing a compatible plasmid encoding int/attP. All three attB sites gave recombinant products, and these were sequenced to verify the presence of the TTC sequence in the attL product (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Sequences of attachment sites in φC31 integration. (A) Natural variation of attB sites in various species of Streptomyces. coeli, S. coelicolor A3 (2) strain M145; hygro, S. hygroscopicus NRRL5491; aureo, S. aureofaciens; cinna, S. cinnamonensis; clavu, S. clavuligerus; longi, S. longisporoflavus 83E6; grise, S. griseus ATCC 12475. (B) Sequences of the attB site from S. coelicolor (attB) and the pseudo-attB sites (pseB1, pseB2, and pseB3). (C) Sequence of the attP site in φC31. The sequence at which crossover occurs (i.e., the core sequence) is marked with XX for the natural attB sites, the pseudo-attB sites, and the attP site. Previously the core sequence was believed to be within the sequence 5′TTG (marked in italics in the S. coelicolor attB sequence in panel A) (13).

Deletion of the attB site in S. coelicolor and S. lividans.

In order to study insertion into secondary attachment sites in the Streptomyces chromosome, it was first necessary to delete the attB site. The attB site lies within a highly conserved gene, SCAC2.06c. Many phage attachment sites are located intragenically, but insertion of the phage often regenerates a functional gene, e.g., by insertion into tRNAs (18) or of phage 21 into the icd gene in E. coli (5). In the case of φC31, however, there appeared to be no evidence that φC31 regenerates the pirin-like ORF, and the generation of a targeted mutation in the absence of phage DNA would test whether SCAC2.06c was essential.

The attB site was deleted from the S. coelicolor and S. lividans chromosomes by allele replacement. A plasmid, pPC30, which contained the 4,115-bp SphI-BamHI fragment encoding attB, was constructed from the cosmid AC2 in pGEM7. Primers PC1 and PC2 were used to amplify pPC30 DNA by inverse PCR. Circularization of the PCR product was achieved by digestion with PstI and self-ligation to form pPC33. Thus, pPC33 contains a 98-bp deletion and as a consequence lacks the attB sequence, containing in its place a PstI site. The effect of the deletion on the expression of SCAC2.06c is shown by the presence of a prematurely terminated polypeptide containing the first 58 amino acids (aa) of the 325-aa ORF and 27 aa read out of frame. The 4,024-bp BamHI-SphI fragment from pPC33 was inserted into the BamHI/SphI sites in pSET151 to form pPC34, and this plasmid was introduced into S. lividans TK24 and S. coelicolor J1929 (ΔpglY derivative of M145; Table 2) by conjugation. Plasmids inserted by either of the homologous regions of DNA flanking the attB deletion (ΔattB) were isolated by selection with thiostrepton, and four independent lines of J1929::pPC34 and TK24::pPC34 were amplified. After several rounds of sporulation on medium lacking thiostrepton, nineteen colonies from each line were then tested for loss of the thiostrepton marker. One of each of the colonies of the S. lividans and S. coelicolor lines (TK24ΔattB line 1 and J1929ΔattB line 4, respectively) yielded thiostrepton-sensitive clones. These were tested by PCR for the presence or absence of the ΔattB using primers PC31 and PC32. A band of 302 bp was obtained when the DNA from the ΔattB clones, now called PCS41 for S. coelicolor J1929ΔattB and PCS13 for S. lividans TK24ΔattB, was used against a band of 393 bp obtained from TK24 and J1929. PCS41 and PCS13 were further analyzed by Southern blotting to verify the presence of ΔattB and the absence of attB (data not shown). There was no obvious difference in phenotype in PCS41 or PCS13 compared to that of the parent strains, J1929 and TK24, and we concluded that SCAC2.06c is not an essential gene under laboratory conditions.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide sequences

| Oligo- nucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| ATTB1 | 5′CGGGATCCGACCC(G/C)TTCATCATGATGGAC |

| ATTB2 | 5′TGGAATTCAGGTT(G/C)ACCCA(C/G)AGCTG(G/C)AG |

| PC1 | 5′AGTCCTGCAGTGAACGGGTCGAGGTGGCGGTAG |

| PC2 | 5′AGTCCTGCAGCGTCGACGGGATCTTCGACCACC |

| PC31 | 5′GTTTCGAGGGCGAGGGCT |

| PC32 | 5′CTGCCACTGCGGATGTCCTG |

| PC20 | 5′GACTGACGGTCGTAAGCACC |

| HS19 | 5′GCTTGGTACCTCTATGGCCCGTACTGACGGACA |

Introduction of pSET152 into the attB deletion strains.

The φC31-derived integrating vector, pSET152, was introduced into PCS41 and PCS13 by conjugation. The frequency of integration of pSET152 into J1929 (attB+) and PCS41 (ΔattB) was 1.5 × 10−3 and 5 × 10−6 transconjugants per spore, respectively. This represents a reduction in the efficiency of conjugation into the ΔattB strain of approximately 300-fold.

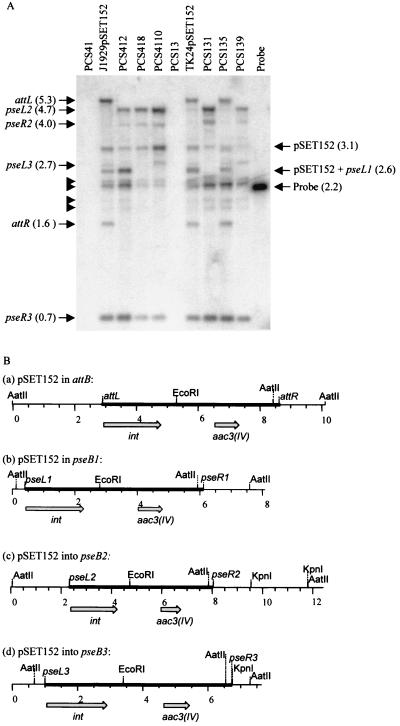

To verify the integrity of the inserted pSET152 and to investigate the site of insertion, genomic DNAs were prepared from transconjugants and probed in a Southern blot with a DNA fragment from pSET152 containing the attP site (Fig. 2). Thus, the probe should detect both of the fragments flanking the insertion site. J1929(pSET152) and TK24(pSET152) gave exactly the same pattern of bands, which is consistent with their very close relatedness. If pSET152 had inserted into the S. coelicolor attB site, bands of 5.3, 1.6, and 3.1 kbp should have been observable (Fig. 2B). These bands are clearly present in the lanes containing TK24(pSET152) and J1929(pSET152) (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 7). However, there are many additional bands hybridizing to the probe. One of these, a band of 2.6 kbp, is consistent with hybridization by the probe to pSET152 inserted as a tandem repeat or as covalently closed circular DNA (Fig. 2A, lanes 2, 7, and 9). The tendency for pSET152 to insert in tandem has been reported previously (M. Paget, personal communication). Bands of other sizes were observed, some of which were of the same sizes as those obtained with genomic DNAs derived from pSET152 insertions into ΔattB strains. As described below, some of these bands were accounted for as bona fide insertions of pSET152 into pseudo-attB sites. This suggests that, even if the attB site is present, pSET152 can also insert into pseudo-attB sites.

FIG. 2.

Integration of pSET152 into S. coelicolor and S. lividans. (A) Southern blot of genomic DNAs probed with a fragment containing the pSET152 attP site. Genomic DNAs from PCS41, J1929(pSET152), PCS412, PCS418, PCS4110, PCS13, TK24(pSET152), PCS131, PCS135, and PCS139 were digested with AatII and EcoRI, separated in a 0.8% agarose gel, blotted onto a membrane filter, and probed with the 2.2-kbp NheI-NcoI fragment from pSET152 (lane 11), which hybridizes to fragments containing the left and right integration endpoints. The fragments corresponding to the left and right boundaries of the insertion sites, i.e., those of attL and attR, result from insertion into attB; pseL1 is the left insertion fragment from pseB1; pseL2 and pseR2 are from insertion into pseB2; and pseL3 and pseR3 are from insertion into pseB3. The fragment sizes are shown in brackets. Bands not identified in this analysis (see text) are indicated by the tailless arrows. (B) Physical maps of pSET152 inserted into the S. coelicolor attB site (a) and the pseudo-attB sites, pseB1(b), pseB2 (c), and pseB3 (d). Chromosomal DNA is represented by thin lines, and pSET152 is represented by thick lines. The numbers represent kilobase pairs. The integrase gene (int) and the apramycin resistance gene [aac3(IV)] from pSET152 are also shown.

The band patterns obtained in the Southern blot analysis of independent transconjugants containing pSET152 insertions, PCS412, PCS418, and PCS4110 in the ΔattB strain of S. coelicolor (PCS41), and PCS131 and PCS139 in the ΔattB strain of S. lividans (PCS13) were extremely similar. This indicated that pSET152 tended to integrate into preferred pseudo-attB sites. As expected, hybridizations to fragments characteristic of pSET152 inserted into the attB site were absent. The band pattern from the transconjugant PCS135 (derived from pSET152 conjugation into the ΔattB strain PCS13) resembled that of TK24(pSET152); i.e., pSET152 appears to have inserted into an attB site. Although PCS13 was taken through several subcultures and one single-colony isolation and the absence of attB was verified by PCR and Southern blotting, it seems that this line still contains attB, presumably in a minority of genomes. PCS135 was not investigated further.

Identification of the pseudo-attB sites.

In order to identify the secondary integration sites, plasmids were rescued from strains into which pSET152 had been inserted by conjugation. Genomic DNA was cleaved with KpnI (an enzyme that does not cleave in pSET152) and self-ligated and was then used to transform E. coli DH5α to resistance to apramycin. Plasmids isolated from these transformants should contain pSET152 and the two fragments of chromosomal DNA from the left and right flanking arms of the insertion site. Plasmids were prepared from five independent transformants derived from J1929(pSET152), PCS412, PCS418, and PCS4110 genomic DNA. Plasmids were also prepared from six independent transformants derived from TK24(pSET152), PCS131, and PCS139 genomic DNA. Surprisingly, when analyzed with MluI, an enzyme that cleaves twice in pSET152, four of five of the plasmids isolated from J1929(pSET152), PCS418, and PCS4110, three of five of those isolated from PCS412, and three of six of those isolated from PCS139 contained only the MluI fragments from pSET152 and no chromosomally derived DNA. This implies that covalently closed circular pSET152 is present in these genomic preparations, despite our inability to detect a 2.6-kbp fragment (indicative of the presence of the fragment containing the attP site) in the ΔattB derivatives PCS4110 and PCS139 (Fig. 2).

The plasmids that did contain chromosomally derived DNA were analyzed further. The sequences to the left and right of the inserted pSET152 were obtained by sequencing with primers PC20 and HS19, respectively (Table 3). Many of the rescued plasmids contained the same insertion endpoints, e.g., pPC4184, pPC41104, pPC1311 to pPC1316, and pPC1391 (Table 3). These plasmids were derived from four independent isolates from the pSET152 conjugations, two derived from the ΔattB S. coelicolor strain (PCS418 and PCS4110) and two derived from the ΔattB S. lividans strain (PCS131 and PCS139). The site at which pSET152 had inserted was called pseB2 (for pseudo-attB site 2) (Fig. 1; Table 3). The insertion of pSET152 into pseB2 is also apparent in the Southern blot analysis of genomic DNAs; the restriction fragments containing the left and right insertion endpoints, pseL2 and pseR2, are 4.7 and 4.0 kbp, respectively (Fig. 2). Indeed, these bands are clearly visible in all of the ΔattB transconjugants, suggesting that all contain pSET152 insertions in pseB2 (Fig. 2A). Faint bands corresponding to rare insertions into pseB2 were also observed in DNA from the TK24(pSET152) transconjugant (Fig. 2A, lane 7). Notably, PCS139 yielded a second plasmid (e.g., pPC1392) containing chromosomal DNA from a different pseudo-attB site, pseB3 (Fig. 1 and 2; Table 3). In the blot of genomic DNA from PCS139, bands corresponding to the left and right insertion endpoints, pseL3 and pseR3, were observed (Fig. 2A, lane 10). Indeed, pseR3 was apparently observed in all the pSET152-containing transconjugants, including the attB+ strains, which also contained bands corresponding to pseL3 (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 7).

TABLE 3.

Sequences of left and right endpoints after integration of pSET152 in S. coelicolor and S. lividans strainsb

| Clone | Rescued plasmid | Sequence of left endpoint | Sequence of right endpoint | Integration site(s) | Cosmid location(s)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J1929(pSET152) | pSET152 | GGGCGTGCCCTTgagttctc | ggtaacctTTGGGCTCCCCG | attB | AC2 |

| PCS412 | pPC4121 | GGGGGTTACGTTgagttctc | ggtaacctTTTGCCTCTCCC | pseB1/pseB2 | E9 and H63 |

| pPC4122 | GGGAGAAGCTTTgagttctc | ggtaacctTTCGGCACGCCG | pseB2/pseB3 | H63 and D82 | |

| PCS418 | pPC4184 | GGGAGAAGCTTCgagttctc | ggtaacctTTTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 |

| PCS4110 | pPC41104 | GGGAGAAGCTTCgagttctc | ggtaacctTTTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 |

| PCS131 | pPC1311 | GGGAGAAGCTTTgagttctc | ggtaacctTCTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 |

| pPC1312 | GGGAGAAGCTTCgagttctc | ggtaacctTTTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 | |

| pPC1313 | GGGAGAAGCTTCgagttctc | ggtaacctTTTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 | |

| pPC1314 | GGGAGAAGCTTCgngttctn | ggtaacctTTTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 | |

| pPC1315 | GGGAGAAGCTTCgagttctc | ggtaacctTTTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 | |

| pPC1316 | GGGAGAAGCTTTgagttctc | ggtaacctTCTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 | |

| PCS139 | pPC1391 | GGGAGAAGCTTCgagttctc | ggtaacctTTTGCCTCTCCC | pseB2 | H63 |

| pPC1392 | CGGTGAGGCGTTgagttctc | ggtaacctTTCGGCACGCCG | pseB3 | D82 | |

| pPC1396 | CGGTGAGGCGTTgagttctc | ggtaacctTTCGGCACGCCG | pseB3 | D82 |

Cosmid map is located at http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor/clone_map.shtml.

Lowercase letters denote attP sequences.

The remaining two rescued plasmids (pPC4121 and pPC4122) were complicated in structure, since the left and right insertion endpoints were derived from two different pseudo-attB sites (Table 3). In plasmid pPS4121, the left flanking region is derived from the pseudo-attB site, pseB1, and the fragment containing the left insertion endpoint at this site is pseL1 (2.6 kbp; Fig. 2). This band is very intense in the blot of PCS412, from which this plasmid was derived (Fig. 2A, lane 3). The right-hand insertion endpoint in this plasmid is identical to pseR3. In plasmid pPC4122, the left insertion endpoint is pseL2 and the right insertion endpoint is pseR3 (Table 3).

Examination of the Southern blot shows that there are bands hybridizing to pSET152 that we have not identified in this study. We propose that these are yet further loci for pSET152 insertion.

Taken together, these data indicate that pSET152 can integrate at pseudo-attB sites in the Streptomyces chromosome, and we have characterized three of these. Furthermore, transconjugants contain pSET152 inserted at multiple loci irrespective of whether the genome is attB+ or ΔattB.

DISCUSSION

The DNA sequences of the preferred chromosomal target, attB, for insertion of the φC31 genome via integrase-attp-directed site-specific recombination were characterized from various Streptomyces species. An alignment of these sequences highlighted positions where sequence variation is tolerated in sites that are active for recombination (Fig. 1). In particular, the core sequence (i.e., the sequence at which the crossover between attB and attP occurs), previously thought to be within 5′TTG, can now be shortened to 5′TT (Fig. 1). A minimal core sequence of 2 bp is consistent with the mechanism of recombination by the serine recombinases (9, 11); as the 2-bp 3′ overhang is (normally) the same in both of the substrates, these form complementary base pairs in the recombinant products. The conservation of other bases in the attB sites was investigated by studying the integration of the vector pSET152, containing φC31 int/attP, into pseudo-attB sites in strains from which the attB site has been deleted.

For integration of pSET152 in S. coelicolor and S. lividans, three preferred pseudo-attB sites were identified. The difference in conjugation frequencies between attB+ and ΔattB S. coelicolor strains indicated that insertion into the attB site is 300 times more efficient than into the secondary sites. Comparison of the sequences of the pseudo-attB sites reported here with those of the attB sites indicated that they are similar, particularly in the sequences immediately flanking the crossover site. The conserved bases in the CLUSTALW alignments (Fig. 1) are proposed to be required for the recognition of attB and pseudo-attB sites by integrase. The conserved 5′GGnG and 5′CnCC sequences, which are located 6 bp to the left and right, respectively, of the core sequence, appear to be particularly well conserved. Pseudo-attP sites have been characterized previously in studies in which a plasmid containing attB was introduced into a human cell line in the presence of a second plasmid expressing integrase (24). The most frequently used pseudo-attP sequence from the human chromosome had 7 out of 8 of the highly conserved bases noted above and 16 of 27 bases identical to those of attP in the region flanking and including the core. Some of these conserved bases may be recognized by integrase at both attP and attB sites.

The core sequence, 5′TT, in two of the pseudo-attB sites, pseB1 and pseB3, is conserved, and analysis of the recombinants indicated that crossover had indeed occurred at this position. However, analysis of the insertions into pseB2 indicated that crossover occurred at 5′TC (Fig. 1), despite the likely formation of a mismatch in the recombinants. Close scrutiny of the sequences of pseL2 and pseR2 shows that if the left endpoint is TT, then the right endpoint is TC and vice versa. The simplest explanation for this close linkage is that replication occurs before any repair takes place. If a repair mechanism is invoked, it is not clear why gene conversion does not occur, i.e., how the same strand can be repaired at right and left endpoints located 5.7 kbp apart in the absence of an obvious strand bias, such as daughter strand bias.

Integrating vectors, particularly those based on the φC31 recombination system, are used widely in Streptomyces research (12). One of the perceived advantages is their single-copy presence in the chromosome. Data presented here indicate that within a transconjugant, pSET152 may be inserted at several positions in the presence or absence of attB. We observed multiple bands in a Southern blot (indicative of insertion of pSET152 at several loci), and we have shown directly by plasmid rescue that within a single transconjugant, the vector can insert at several sites (see, e.g., PCS139 in Table 3). These data indicate that the introduction of pSET152 by conjugation into Streptomyces hyphae involves multiple independent recombination events. A single transconjugant colony, therefore, may contain a number of different chromosomes.

The presence of apparently tandemly repeated copies of pSET152 in the attB site may also be the consequence of multiple independent recombination events. Although recombination between attP or attB and any other recombination site such as attP/attL has never been observed in vitro or in E. coli, we cannot rule out the possibility that Streptomyces might contain a host factor that facilitates such recombination in vivo. Possibly pSET152 can integrate at attL or attR sites via attP/attL or attP/attR. If it occurs, this aberrant reaction must be specific to the attL and attR sites and not to the left and right endpoints of the pseudo-attB sites, as tandem repeats of pSET152 in the pseudo-attB sites were not generally observed (indicated by the absence of a 2.6-kbp band in Fig. 2). Alternatively, the generation of tandem repeats of pSET152 in the attB+ strains, but not in the ΔattB strains, may be a consequence of the rate of integration. If the rate of recombination into the attB site is rapid, integration occurs early during the mating period and the integrated plasmid is multiplied by replication of the genome. If hyphae containing integrated pSET152 then receive a further copy of pSET152, this further copy may integrate by homologous recombination to generate a tandem repeat or may insert at a pseudo-attB site. If insertion of pSET152 into the pseudo-attB sites in the ΔattB strains is much less efficient, integration will occur later during the mating period and the possibility is reduced that a hyphal compartment that already contains an integrated plasmid will receive a further copy of the plasmid. Therefore, the opportunity for homologous recombination under these circumstances is also reduced.

A consequence of the insertion of pSET152 into multiple sites is apparent from the analysis of two of the rescued plasmids, pPC4121 and pPC4122. These plasmids have left and right insertions endpoints derived from different pseudo-attB sites. It is possible that this arrangement occurs as a consequence of independent recombination events involving pseB1 and pseB2 (for pPC4121) or pseB2 and pseB3 (for pPC4122), followed by recombination between the inserted vectors to form a deletion in a subpopulation of genomes within the colony. Prerequisite to these proposed rearrangments is that independent insertions into either the same chromosome or different chromosomes which have then recombined have occurred. The findings resulting from the use of these plasmids indicate that large chromosomal rearrangements can occur within strains containing pSET152.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Leadlay, Simon Baumberg, and Iain Hunter for strains and Jennifer Hurd for recombination assays.

Funding was provided by a BBSRC project grant and by a Nuffield summer studentship (to S.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bedford, D. J., C. Laity, and M. J. Buttner. 1995. Two genes involved in the phase-variable φC31 resistance mechanism of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 177:4681-4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentley, S. D., K. F. Chater, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, G. L. Challis, N. R. Thomson, K. D. James, D. E. Harris, M. A. Quail, H. Kieser, D. Harper, A. Bateman, S. Brown, G. Chandra, C. W. Chen, M. Collins, A. Cronin, A. Fraser, A. Goble, J. Hidalgo, T. Hornsby, S. Howarth, C. H. Huang, T. Kieser, L. Larke, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, S. O'Neil, E. Rabbinowitsch, M. A. Rajandream, K. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, D. Saunders, S. Sharp, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Taylor, T. Warren, A. Wietzorrek, J. Woodward, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, and D. A. Hopwood. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bierman, M., R. Logan, K. O'Brien, E. T. Seno, R. N. Rao, and B. E. Schoner. 1992. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene 116:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breüner, A., L. Brøndsted, and K. Hammer. 1999. Novel organization of genes involved in prophage excision identified in the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1. J. Bacteriol. 181:7291-7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell, A., S. J. Schneider, and B. Song. 1992. Lambdoid phages as elements of bacterial genomes (integrase/phage21/Escherichia coli K-12/icd gene). Genetica 86:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chater, K. F. 1998. Taking a genetic scalpel to the Streptomyces colony. Microbiology 144:1465-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grindley, N. D. F. 1994. Resolvase-mediated site-specific recombination, p. 236-267. In F. Eckstein and D. M. J. Lilley (ed.), Nucleic acids and molecular biology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 8.Groth, A. C., E. C. Olivares, B. Thyagarajan, and M. P. Calos. 2000. A phage integrase directs efficient site-specific integration in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5995-6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatfull, G., and N. Grindley. 1988. Resolvases and DNA-invertases: a family of enzymes active in site-specific recombination, p. 357-396. In R. Kucherlapati and G. Smith (ed.), Genetic recombination. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Hopwood, D. A. 1999. Forty years of genetics with Streptomyces: from in vivo through in vitro to in silico. Microbiology 145:2183-2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson, R. C., and M. F. Bruist. 1989. Intermediates in Hin-mediated DNA inversion: a role for Fis and the recombinational enhancer in the strand exchange reaction. EMBO J. 8:1581-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Colney, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 13.Kuhstoss, S., and R. N. Rao. 1991. Analysis of the integration function of the streptomycete bacteriophage phic31. J. Mol. Biol. 222:897-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lomovskaya, N., L. Fonstein, X. Ruan, D. Stassi, L. Katz, and C. R. Hutchinson. 1997. Gene disruption and replacement in the rapamycin-producing Streptomyces hygroscopicus strain ATCC 29253. Microbiology 143:875-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lomovskaya, N. D., K. F. Chater, and N. M. Mkrtumian. 1980. Genetics and molecular biology of Streptomyces bacteriophages. Microbiol. Rev. 44:206-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Smith, M. C. M., and H. M. Thorpe. 2002. Diversity in the serine recombinases. Mol. Microbiol. 44:299-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith, M. C. M., and C. E. D. Rees. 1999. Exploitation of bacteriophages and their components. Methods Microbiol. 29:97-132. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stark, W. M., M. R. Boocock, and D. J. Sherratt. 1992. Catalysis by site-specific recombinases. Trends Genet. 8:432-439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabakov, V. I., T. A. Voeikova, I. L. Tokmakova, A. P. Bolotin, E. I. Vavilova, and D. Lomovskaia. 1994. Intergeneric Escherichia coli-Streptomyces conjugation as a means for the transfer of conjugative plasmids into producers of antibiotics chlortetracycline and bialaphos. Genetika 30:57-61. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomason, L. C., R. Calendar, and D. W. Ow. 2001. Gene insertion and replacement in Schizosaccharomyces pombe mediated by the Streptomyces bacteriophage φC31 site-specific recombination system. Mol. Genet. Genomics 265:1031-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorpe, H. M., and M. C. M. Smith. 1998. In vitro site-specific integration of bacteriophage DNA catalyzed by a recombinase of the resolvase/invertase family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5505-5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorpe, H. M., S. E. Wilson, and M. C. M. Smith. 2000. Control of directionality in the site-specific recombination system of the Streptomyces phage φC31. Mol. Microbiol. 38:232-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thyagarajan, B., E. C. Olivares, R. P. Hollis, D. S. Ginsburg, and M. P. Calos. 2001. Site-specific genomic integration in mammalian cells mediated by phage φC31 integrase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3926-3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trepanier, N. K., S. E. Jensen, D. C. Alexander, and B. K. Leskiw. 2002. The positive activator of cephamycin C and clavulanic acid production in Streptomyces clavuligerus is mistranslated in a bldA mutant. Microbiology 148:643-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]