Abstract

Tritrichomonas foetus, a venereal pathogen of cattle, was recently identified as an inhabitant of the large intestine in young domestic cats with chronic diarrhea. Recognition of the infection in cats has been mired by unfamiliarity with T. foetus in cats as well as misdiagnosis of the organisms as Pentatrichomonas hominis or Giardia sp. when visualized by light microscopy. The diagnosis of T. foetus presently depends on the demonstration of live organisms by direct microscopic examination of fresh feces or by fecal culturing. As T. foetus organisms are fastidious and fragile, routine flotation techniques and delayed examination and refrigeration of feces are anticipated to preclude the diagnosis in numerous cases. The objective of this study was to develop a sensitive and specific PCR test for the diagnosis of feline T. foetus infection. A single-tube nested PCR was designed and optimized for the detection of T. foetus in feline feces by using a combination of novel (TFITS-F and TFITS-R) and previously described (TFR3 and TFR4) primers. The PCR is based on the amplification of a conserved portion of the T. foetus internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region (ITS1 and ITS2) and the 5.8S rRNA gene. The absolute detection limit of the single-tube nested PCR was 1 organism, while the practical detection limit was 10 organisms per 200 mg of feces. Specificity was examined by using P. hominis, Giardia lamblia, and feline genomic DNA. Our results demonstrate that the single-tube nested PCR is ideally suited for (i) diagnostic testing of feline fecal samples that are found negative by direct microscopy and culturing and (ii) definitive identification of microscopically observable or cultivated organisms.

Tritrichomonas foetus is a prevalent and economically important venereal cause of infertility and abortion in naturally bred cattle (1). The organism has also been described as a parasite of the porcine gastrointestinal and nasal mucosa, where its pathogenicity is uncertain (7, 15). Recently, T. foetus was identified in fecal samples from large numbers of cats with chronic large-bowel diarrhea (9). Naturally infected cats are typically young (≤1 year old) and from dense housing conditions, where the infection is transmitted by fecal-oral contamination (9). Following experimental infection, T. foetus colonizes the feline ileum, cecum, and colon, resulting in diarrhea characteristic of the natural infection (8). The time and means of transmission of T. foetus to the domestic cat population is unknown. Presently, there are no effective treatments for symptoms or antimicrobial treatments. Thus, much remains to be studied regarding the origin and mode of transmission of this emerging pathogen and the pathogenesis of feline trichomoniasis. The development of sensitive and specific diagnostic tools is essential to the success of future research efforts.

At present, the diagnosis of T. foetus infection in cats is limited to microscopic examination of saline-diluted feces for the presence of motile trophozoites or culturing of feces in supportive media, such as modified Diamond's medium (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) (9) or In Pouch TF medium (Biomed Diagnostics, San Jose, Calif.) (J. L. Gookin, M. E. Stebbins, M. F. Poore, and M. G. Levy, J. Vet. Intern. Med. 16:345, abstr. 74, 2002).

Because diagnosis depends on the demonstration of live organisms, fecal samples must be fresh, preferably diarrheic, and processed expeditiously (8). Death of organisms due to refrigeration or delayed processing of feces likely results in frequent occurrences of false-negative results. Furthermore, positive identification of the infecting organisms is problematic, as T. foetus cannot be reliably differentiated from other intestinal trichomonads, such as Pentatrichomonas hominis, on the basis of light microscopy or selective cultivation. This situation has resulted in confusion in the veterinary community with regard to the species of trichomonad that is responsible for feline infections (13, 14; M.G. Levy, J. L. Gookin, M. F. Poore, M. Dykstra, and R. W. Litaker, J. Vet. Intern. Med. 15:315, abstr. 173, 2001).

In the present study, we sought to develop a sensitive PCR for the specific detection of T. foetus in feline fecal samples. Primers were designed to amplify a 208-bp fragment of T. foetus internal transcribed spacer region 1 (ITS1) and 5.8S ribosomal DNAs (rDNAs). The sensitivity of these novel primers was compared to that of primers designed by Felleisen et al. (5). The latter primers have been demonstrated to specifically amplify a 347-bp fragment of T. foetus including 5.8S and flanking ITS1 and ITS2 rDNAs from bovine prepucial or vaginal samples. Our 208-bp product is nested within the sequence amplified by the primers of Felleisen et al. Optimal extraction of DNA and amplification of T. foetus from feline feces were obtained by using a commercially available DNA extraction kit with modifications for the elimination of fecal inhibitors and a single-tube nested PCR with primer pairs TFITS-F-TFITS-R and TFR3-TFR4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protozoa.

T. foetus (NCSU Tfs-1; GenBank accession no. AF466751) was isolated from the feces of a 6-month-old sexually intact female domestic longhair cat that had chronic large-bowel diarrhea (8). Cryopreserved stabilates of the isolate were thawed and cultivated in modified Diamond's medium at 37°C. The identity of the isolate, which was used for all in vitro studies and experimental infections, was determined by light microscopy, scanning and transmission electron microscopy, and sequence analyses of cloned 18S, ITS1, 5.8S, and ITS2 rDNAs (Levy et al., J. Vet. Intern. Med., abstr. 173). P. hominis (ATCC 30098) and a feline isolate of Giardia lamblia (ATCC 50163) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, Va., and cultured at 37°C in the recommended media. Modified Diamond's medium was incapable of supporting the growth of either P. hominis or G. lamblia (Gookin et al., J. Vet. Intern. Med., abstr. 74).

Cultivation of T. foetus from feline feces.

The method that we used for the cultivation of T. foetus from feline feces has been published elsewhere (8). Briefly, 0.1 g of freshly collected feces was suspended in 10 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered 0.9% saline (PBS; pH 7). A 100-μl aliquot of this solution (i.e., 0.001 g of feces) was used to inoculate a culture tube containing 10 ml of antibiotic-fortified (106 U of penicillin, 15 g of streptomycin, and 2 mg of amphotericin B/liter) modified Diamond's medium (Remel), and the mixture was incubated at 37°C.

Preparation of DNA. (i) In vitro-cultivated T. foetus and spiked feline feces.

To determine the absolute sensitivity of each PCR, in vitro-cultivated T. foetus (NCSU Tfs-1) organisms in the logarithmic phase of growth were washed three times by centrifugation for 5 min at 1,500 × g in sterile PBS and counted in a hemocytometer by using a light microscope. Organisms were serially diluted in PBS, and genomic DNA was extracted from 200-μl aliquots containing 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, or 1,000 organisms by using a QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) in accordance with manufacturer instructions. To test the practical sensitivity of each PCR, 20-μl aliquots containing 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, or 1,000 organisms (prepared as described above) were added to 200-mg samples of feline feces obtained from a T. foetus culture-negative specific-pathogen-free cat. DNA was extracted from spiked fecal samples by using a QIAamp DNA stool minikit (Qiagen), which was modified for the optimal elimination of PCR inhibitors. Modifications of the manufacturer instructions included an extended proteinase K digestion (20 μl of proteinase K at 56°C for 1 h), a second wash in guanidium chloride (buffer AW1), and an additional centrifugation step following the final wash (buffer AW2).

(ii) Feces from cats with experimental T. foetus infection.

DNA was extracted from 53 fecal samples collected from four specific-pathogen-free cats that were experimentally infected with T. foetus (NCSU Tfs-1) (8). The 53 samples were selected at random from a total of 178 fecal samples collected from the four cats over a 7-month period, during which chronic infection was documented by fecal culturing. Feces had been voided or collected by insertion of a lubricated plastic loop into the rectum and had been kept frozen at −70°C for approximately 3 years. At the time of their original collection, none of the 178 fecal samples had T. foetus organisms present in sufficient numbers to be detected by light microscopy. Among the 53 samples selected, 30 (57%) were historically positive after culturing in modified Diamond's medium. For the present study, each fecal sample was thawed on ice, and 200 mg was used for DNA extraction. Extraction was performed by using a QIAamp DNA stool minikit in accordance with manufacturer instructions (26 samples) or with modifications adopted to optimize the elimination of PCR inhibitors (27 samples).

(iii) Feces from cats with natural T. foetus infection.

Voided fecal samples were obtained from three cats with chronic diarrhea and positive fecal culture results for T. foetus. Fecal samples were frozen at −20°C for 1 to 2 months prior to DNA extraction. Extraction was performed by using 200-mg fecal samples and a QIAamp DNA stool minikit in accordance with manufacturer instructions.

(iv) Other protozoa.

A logarithmic-phase culture of P. hominis (ATCC 30098) and a feline isolate of G. lamblia (ATCC 50163) were each centrifuged for 5 min at 1,500 × g. Genomic DNA was extracted from a 200-μl aliquot of pelleted organisms by using a QIAamp DNA minikit in accordance with manufacturer instructions.

Primer design.

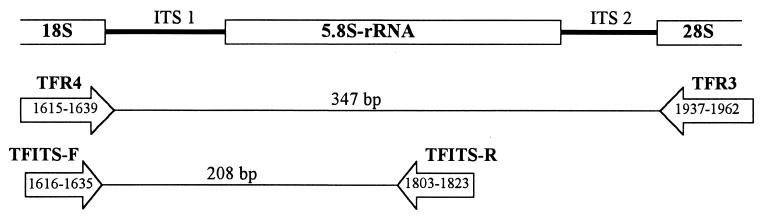

Primer pairs amplifying ITS1 and the 5.8S region of the T. foetus rRNA gene unit were evaluated alone and in combination (Table 1). Primers TFR3 and TFR4 were developed by Felleisen et al. (5). Primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R were designed by us. Primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa. The relationship of primers to the rRNA gene unit of T. foetus is depicted schematically in Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Primer designations, sequences, annealing temperatures, and product sizes

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Annealing temp (°C) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TFR3 | CGGGTCTTCCTATATGAGACAGAACC | 61.2 | 347 |

| TFR4 | CCTGCCGTTGGATCAGTTTCGTTAA | 59.7 | |

| TFITS-F | CTGCCGTTGGATCAGTTTCG | 57.3 | 208 |

| TFITS-R | GCAATGTGCATTCAAAGATCG | 54.3 |

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the primer sites used for PCR amplification with respect to the rRNA gene unit of T. foetus. The positions of the boundaries and the 3′ ends of the primers are indicated in reference to T. foetus UT-1 (GenBank accession no. M81842) (2).

PCR. (i) Standard PCR.

Reaction conditions for PCR with primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R were optimized for MgCl2 (1.0 to 5.0 by increments of 0.5), annealing temperature (50.1 to 64°C by increments of 2.78°C), and template DNA volume (1, 5, and 10 μl). Reaction conditions for PCR with primers TFR3 and TFR4 were similarly optimized, with the exception of the use of a previously published annealing temperature (67°C) (5). The optimized conditions for standard PCR of T. foetus in feces were used with a 100-μl reaction volume of PCR buffer II (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) containing 1.25 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), 5 mM MgCl2, 25 pmol of each primer (TFR3 and TFR4 or TFITS-F and TFITS-R), 200 μM each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 10 μg of bovine serum albumin (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), and 5 μl of DNA template. DNA amplification was performed with a thermal cycler (PCR Express; Thermo Hybaid, Middlesex, United Kingdom) at the following temperature profiles: TFR3-TFR4—initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 67°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s for 50 cycles, followed by a final extension for 5 min at 72°C; and for TFITS-F-TFITS-R—initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 57°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s for 50 cycles, followed by a final extension for 5 min at 72°C.

(ii) Single-tube nested PCR.

Reaction conditions for the single-tube nested PCR were optimized for TFR3-TFR4 and TFITS-F-TFITS-R annealing temperature (65, 67, 70, 72, and 74°C) and TFR3-TFR4 concentration (1.25, 2.5, and 5 pmol). The optimized conditions for the single-tube nested PCR of T. foetus in feces were used with a 100-μl reaction volume of PCR buffer II containing 1.25 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), 5 mM MgCl2, 1.25 pmol each of primers TFR3 and TFR4, 25 pmol each of primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R, 200 μM each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 10 μg of bovine serum albumin, and 5 μl of DNA template. DNA amplification was performed with a thermal cycler (PCR Express) at the following temperature profiles: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and annealing and extension at 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles; denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 57°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s for 50 cycles; and a final extension for 5 min at 72°C.

(iii) Detection of inhibitors and controls.

To avoid PCR contamination, DNA extraction, reaction preparations, thermal cycling, electrophoresis, and detection of amplicons were performed in separate laboratories. During DNA extraction, a tube containing feces with no T. foetus and a tube containing PBS were processed in parallel with other study samples to detect any genomic DNA contamination. Negative control tubes were included in each PCR experiment to detect any amplicon contamination. Instead of sample DNA, these tubes received either 5 μl of sterile water, 5 μl of DNA extracted from feces containing no T. foetus, or 5 μl of “DNA” extracted from sterile PBS. A single positive control tube was included in each PCR experiment, and this tube received 0.5 μl of purified T. foetus genomic DNA and 4.5 μl of sterile water instead of sample DNA. For all samples from which no product was amplified, the presence of endogenous PCR inhibitors was ruled out by the addition of 0.5 μl of purified T. foetus genomic DNA to a second reaction.

PCR product detection and analysis.

Amplicons were visualized by UV illumination after electrophoresis of 10 μl of the reaction solution in a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Reaction products from spiked fecal samples, feces from cats with natural infection, and feces from cats experimentally infected with T. foetus were purified (QIAquick PCR purification kit; Qiagen) and sequenced by a commercial laboratory (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Automated DNA Sequencing Facility).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical comparisons of the sensitivity of standard PCR versus that of the single-tube nested PCR were performed by using a Fisher exact test. Significance was assigned a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Extraction of DNA from feline fecal samples.

Optimal extraction of DNA from feline fecal samples was achieved by using a commercial kit (QIAamp DNA stool minikit) with modifications of the manufacturer instructions to minimize the recovery of PCR inhibitors. These modifications included prolonged incubation of each sample in proteinase K solution (20 μl) for 1 h at 56°C (manufacturer step 10), washing the extracted DNA twice with 500 μl of buffer AW1 (manufacturer step 15), and adding an extra centrifugation step after the final wash in buffer AW2 (manufacturer step 16). When DNA extraction was performed by using the QIAamp DNA stool minikit without modifications of the manufacturer instructions, the PCR was 10 times less sensitive for the detection of T. foetus in spiked fecal samples (100 organisms per 200 mg of feces versus 10 organisms per 200 mg of feces), and we could not consistently extract DNA from feline feces despite the absence of PCR inhibitors.

Sensitivities of standard PCR and single-tube nested PCR. (i) Absolute detection limits of standard PCR.

The absolute detection limit of primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R was determined by using aliquots of serially diluted T. foetus ranging from 1,000 to 0.01 organisms per 200 μl. Under optimized PCR conditions, the absolute detection limit of primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R was 1 organism per 200 μl (5 organisms per ml). The PCR was able to detect 1 organism 70% of the time (7 of 10 reactions), 10 organisms 90% of the time (9 of 10 reactions), and 100 organisms 100% of the time (10 of 10 reactions). Primers TFR3 and TFR4 were previously reported by Felleisen et al. to be similarly capable of detecting as few as one T. foetus organism (5).

(ii) Detection of T. foetus in feline feces by standard PCR and single-tube nested PCR.

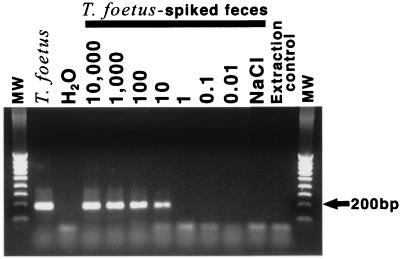

The practical detection limit of primers TFR3 and TFR4 or primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R was determined by using 200-mg samples of feline feces spiked with 20-μl aliquots of serially diluted T. foetus ranging from 1,000 to 0.01 organisms. The results are shown in Table 2. Each primer pair detected as few as 10 organisms per 200 mg of feces. Although 10 organisms were detected more frequently by TFITS-F-TFITS-R and 100 organisms were detected more frequently by TFR3-TFR4, these differences were not statistically significant. In contrast, primers TFR3 and TFR4 and primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R used together in a single-tube nested PCR (Fig. 2) detected 10 organisms per 200 mg of feces 90% of the time and 100 organisms per 200 mg of feces 100% of the time. This frequency was significantly greater than that observed by using standard PCR with primers TFR3 and TFR4 alone (Table 2) (P = 0.01; Fisher exact test). Sequence analysis of the 208-bp products that were amplified by single-tube nested PCR of spiked feline fecal samples revealed complete sequence identity with T. foetus (GenBank accession no. AF466751).

TABLE 2.

Practical detection limits of standard and single-tube nested PCRs for the detection of T. foetus in feline fecal samplesa

| PCR and primer pair | No. (%) of positive PCR reactions obtained with DNA extracted from 200-mg fecal samples after spiking with the following no. of T. foetus organisms:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 100 | 10 | 1 | |

| Standard | ||||

| TFR3-TFR4 | 9 (90) | 10 (100) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) |

| TFITS-F-TFITS-R | 10 (100) | 6 (60) | 7 (70) | 0 (0) |

| Nested | 10 (100) | 10 (100) | 9 (90)* | 0 (0) |

The detection limit was 10 organisms per 200 mg of feces. The nested PCR was more sensitive for the demonstration of 10 T. foetus organisms per 200 mg of feces than were primers TFR3 and TFR4 alone (∗, P < 0.05; Fisher exact test).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of single-tube nested PCR amplification products with primers TFR3 and TFR4 and primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. From left to right, lanes show the following: molecular weight (MW) markers; T. foetus genomic DNA; sterile water (PCR contamination control); DNA extracted from feline fecal samples (200 mg) spiked with 20-μl aliquots of 10,000 to 0.01 cultivated T. foetus organisms; feline fecal DNA (no T. foetus) (NaCl); DNA extracted from sterile water (genomic DNA contamination control) (extraction control); and molecular weight (MW) markers.

Single-tube nested PCR of fecal samples from cats with experimental T. foetus infection.

Fifty-three fecal samples selected at random from 178 samples collected over a 4-month period from four cats experimentally infected with T. foetus (NCSU Tfs-1) were analyzed by single-tube nested PCR. All cats were chronically infected. Fecal samples had been frozen for 3 years and were historically negative by direct examination for T. foetus organisms, while 57% (30 of 53) were positive after culturing in modified Diamond's medium. Two of the samples were discarded from analysis due to the presence of endogenous PCR inhibitors that could not be eliminated with the modified extraction procedure. The results of the analysis of the remaining 51 samples were as follows. Compared to culturing at the time of collection (55% positive; 28 samples), single-tube nested PCR of the frozen fecal samples detected fewer numbers of T. foetus-infected cats (39% positive; 20 samples). However, PCR identified an additional 10 fecal samples (20%) not diagnosed by means of culturing alone. When used in combination, culturing and single-tube nested PCR of feces correctly identified 38 fecal samples (75%) as positive for T. foetus. Sequence analysis of the 208-bp products that were amplified by single-tube nested PCR of fecal samples from experimentally infected cats revealed complete sequence identity with T. foetus (GenBank accession no. AF466751).

Single-tube nested PCR of fecal samples from cats naturally infected with T. foetus.

Fecal samples from three cats that had chronic diarrhea and positive fecal cultures for T. foetus yielded reproducible and robust amplification of T. foetus DNA after single-tube nested PCR. Sequence analysis of the 208-bp products that were amplified by single-tube nested PCR of fecal samples from naturally infected cats revealed complete sequence identity with T. foetus (GenBank accession no. AF466751).

Specificity of single-tube nested PCR.

No amplification products were observed when single-tube nested PCR was performed with purified P. hominis, G. lamblia, or feline genomic DNA as a template.

DISCUSSION

Several investigators have demonstrated that the rRNA gene unit of T. foetus is a highly suitable target for amplification by PCR (2, 3, 5, 6, 12). Twelve copies of the rRNA gene unit are present in the T. foetus genome (2). Felleisen et al. (5) compared the 5.8S rRNA and flanking ITS1 and ITS2 DNA sequences from various geographically distinct T. foetus isolates and from related trichomonads. The results of these studies and others established that the rRNA gene unit sequence is highly conserved among T. foetus isolates and reliably distinguishes T. foetus from related trichomonads, including Trichomonas vaginalis, Trichomonas gallinae, Tetratrichomonas gallinarum, Trichomonas tenax, and P. hominis (4, 6). From these rRNA gene sequence data, primers TFR3 and TFR4 were designed to specifically amplify a 347-bp fragment of T. foetus DNA by PCR (5). These primers have been used with various degrees of success for the PCR diagnosis of T. foetus infection in cattle (3, 5, 12).

Based on the potential for the specific and sensitive diagnosis of T. foetus infection, we chose to examine the efficacy of primers TFR3 and TFR4 for PCR detection of T. foetus in spiked feline fecal samples. Under optimized conditions, PCR with primers TFR3 and TFR4 was able to detect 30% of fecal samples spiked with approximately 50 organisms per g of feces. These results are comparable to those reported in studies of bovine trichomoniasis, where the practical sensitivity of PCR with primers TFR3 and TFR4 has been reported to range from 20 to 50 organisms per ml of prepucial smegma or vaginal mucus (3, 5, 12).

We sought to improve the sensitivity of PCR for the detection of T. foetus in feline feces by designing a second pair of primers (TFITS-F and TFITS-R) that amplify a 208-bp fragment of the rRNA gene unit that lies internal to the sequence amplified by primers TFR3 and TFR4 (Fig. 1). These internal primers had a lower midpoint annealing temperature than either TFR3 or TFR4 (Table 1). While TFR3-TFR4 yielded robust amplification products over a wide range of temperatures (65 to 74°C), TFITS-F-TFITS-R yielded only weak amplification products at temperatures of ≥72°C. This differential annealing at 72°C made possible the use of both primer pairs in a single-tube nested PCR. The first round of PCR was performed at an annealing temperature of 72°C, which favored preferential amplification by the outer primer pair (TFR3-TFR4). The second round of PCR was performed at the optimal annealing temperature (57°C) of the inner primer pair (TFITS-F-TFITS-R). Interference by the outer primer pair in the second round of PCR was prevented by optimizing the concentration of primers TFR3 and TFR4 to ensure their consumption in the first round of PCR.

Under optimized conditions, PCR with primers TFITS-F and TFITS-R alone did not result in an overall improvement in test sensitivity compared to that of PCR with primers TFR3 and TFR4. Although there was an increase in sensitivity from 30 to 70% for the detection of 50 organisms per g of feces, there was a decrease in sensitivity from 100 to 60% for the detection of 500 organisms per g of feces, compared to the results obtained with primers TFR3 and TFR4. Based on our chosen sample sizes, these differences were not statistically significant. In contrast, the use of both primer pairs in a single-tube nested PCR resulted in a significant increase in test sensitivity compared to that of PCR with primers TFR3 and TFR4 alone; the combination detected 50 organisms per g of feces 90% of the time and 500 organisms per g of feces 100% of the time (Table 2).

The practical application of our single-tube nested PCR for the detection of T. foetus was investigated by using frozen fecal samples that had been collected from chronically infected cats experimentally inoculated with the organism. Our results demonstrated that the single-tube nested PCR alone was not superior to fecal culturing (performed at the time of sample collection) for the diagnosis of T. foetus. Importantly, a 200-fold smaller sample of feces is used for fecal culturing (1 mg) than for the extraction of DNA for PCR (200 mg). As such, these results reflect the practical performance of each method as applied to the detection of T. foetus in feces. The combined performance of fecal culturing and single-tube nested PCR was 75% positive results, considerably higher than that of either technique alone (55 and 39% positive results, respectively). Accordingly, single-tube nested PCR of culture-negative fecal samples is anticipated to increase the positive diagnosis of T. foetus infection by 20%. The occurrence of PCR-positive but culture-negative results was attributed to delayed culturing of voided fecal samples leading to a decrease in the numbers of viable T. foetus organisms. The occurrence of false-positive culture or PCR results in these studies is considered unlikely. Cats were repeatedly culture and PCR negative prior to experimental infection (8), and our culture technique with modified Diamond's medium does not foster the growth of either P. hominis or G. lamblia. Additionally, all positive PCR products were sequenced.

There are several likely explanations for our observation that PCR was not superior to fecal culturing for the diagnosis of experimental feline T. foetus infection. First, this group of fecal samples was likely to contain very few T. foetus organisms. Although all cats were chronically infected, each was largely asymptomatic and only fecal samples that were found negative for T. foetus by direct microscopic examination were tested by PCR. Further, only 55% of the samples examined by PCR were culture positive at the time of their collection. In contrast, cats having diarrhea secondary to naturally acquired infection by T. foetus were consistently found positive by PCR. Further studies will be necessary to compare the practical sensitivities of PCR and culturing for naturally infected cats with T. foetus-related diarrhea.

Studies of cattle have been similarly unable to demonstrate a greater sensitivity of PCR alone than of culturing for testing biological samples for T. foetus organisms (3, 5, 10). This discrepancy has been attributed to DNA degradation and the presence of inherent PCR inhibitors in smegma and mucus, which decrease the sensitivity of PCR (3, 12). Fecal samples are considered to be among the most complex specimens for direct PCR testing because of the presence of inherent PCR inhibitors, such as heme, bilirubins, bile salts, and complex carbohydrates, which are often coextracted along with pathogen DNA (11). Optimization of the fecal DNA extraction procedure was critical to the success of our PCR studies. We found that strict adherence to manufacturer instructions in the use of the QIAamp DNA stool minikit resulted in less sensitive PCR results and inconsistent recovery of amplifiable DNA. On the basis of recommendations from Qiagen, considerable improvement in reproducibility and sensitivity was obtained by optimizing the duration and temperature of proteinase K digestion and by adding an additional wash step prior to DNA elution.

T. foetus is commonly mistaken as Giardia sp. or P. hominis when feces are examined by veterinary practitioners by using light microscopy. In the present study, our single-tube nested PCR did not amplify genomic DNA from either a feline isolate of G. lamblia or P. hominis. Thus, PCR affords a definitive diagnosis of T. foetus infections. Additionally, nonspecific amplification products of feline fecal or genomic DNA were not seen. Based on the 100% identity of the T. foetus and Tritrichomonas suis rRNA gene unit sequences (6), single-tube nested PCR cannot distinguish between these two organisms. While T. foetus causes venereal trichomoniasis in cattle and T. suis inhabits porcine nasal and intestinal mucosa, these organisms display little host specificity and are considered to be strains of the same species (5, 6, 15). Therefore, the results of our single-tube nested PCR do not provide insight as to the host of origin of the feline organism.

The results of the present study suggest that the single-tube nested PCR is ideally suited for diagnostic testing of feline fecal samples found negative by direct microscopy and culturing and additionally allows for the definitive identification of microscopically observable or cultivated organisms as T. foetus.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Fort Dodge Animal Health. J. L. Gookin is presently supported by a career training award from the National Institutes of Health (K08 DK 02868).

We thank Matthew Poore, Martha Armstrong, and Mondy Lamb for technical assistance and Marty Stebbins for help with statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.BonDurant, R. H. 1997. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of trichomoniasis in cattle. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food. Anim. Pract. 23:345-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakrabarti, D., J. B. Dame, R. R. Gutell, and C. A. Yowell. 1992. Characterization of the rDNA unit and sequence analysis of the small subunit rRNA and 5.8S rRNA genes from Tritrichomonas foetus. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 52:75-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, X.-G., and J. Li. 2001. Increasing the sensitivity of PCR detection in bovine prepucial smegma spiked with Tritrichomonas foetus by the additon of agar and resin. Parasitol. Res. 87:556-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado-Viscogliosi, P., E. Viscogliosi, D. Gerbod, J. Kulda, M. L. Sogin, and V. P. Edgcomb. 2000. Molecular phylogeny of parabasalids based on small subunit rRNA sequences, with emphasis on the Trichomonadinae subfamily. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 47:70-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felleisen, R. S. J., N. Lambelet, P. Bachmann, J. Nicolet, N. Muller, and B. Gottstein. 1998. Detection of Tritrichomonas foetus by PCR and DNA enzyme immunoassay based on rRNA gene unit sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:513-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felleisen, R. S. J. 1997. Comparative sequence analysis of 5.8S rRNA genes and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of trichomonadid protozoa. Parasitology 115:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald, P. R., A. E. Johnson, D. M. Hammond, J. L. Thorne, and C. P. Hibler. 1958. Experimental infection of young pigs following intranasal inoculation with nasal, gastric, or cecal trichomonads from swine or with Trichomonas foetus. J. Parasitol. 44:597-602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gookin, J. L., M. G. Levy, J. M. Law, M. G. Papich, M. F. Poore, and E. B. Breitschwerdt. 2001. Experimental infection of cats with Tritrichomonas foetus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62:1690-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gookin, J. L., E. B. Breitschwerdt, M. G. Levy, R. B. Gager, and J. G. Benrud. 1999. Diarrhea associated with trichomonosis in cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 215:1450-1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho, M. S., P. A. Conrad, P. J. Conrad, R. B. LeFebvre, E. Perez, and R. H. BonDurant. 1994. Detection of bovine trichomonosis with a specific DNA probe and PCR amplification system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:98-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland, J. L., L. Louie, A. E. Simor, and M. Louie. 2000. PCR detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 directly from stools: evaluation of commercial extraction methods for purifying fecal DNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4108-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker, S., Z.-R. Lun, and A. Gajadhar. 2001. Application of a PCR assay to enhance the getection and identification of Tritrichomonas foetus in cultured prepucial samples. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 13:508-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romatowski, J. 1996. An uncommon protozoan parasite (Pentatrichomonas hominis) associated with colitis in three cats. Feline Pract. 24:10-14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romatowski, J. 2000. Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in four kittens. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 216:1270-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Switzer, W. P. 1951. Atrophic rhinitis and trichomonads. Vet. Med. 46:478-481. [Google Scholar]