Abstract

Denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) was evaluated as a rapid screening and identification method for DNA sequence variation detection in the quinolone resistance-determining region of gyrA from Salmonella serovars. A total of 203 isolates of Salmonella were screened using this method. DHPLC analysis of 14 isolates representing each type of novel or multiple mutations and the wild type were compared with LightCycler-based PCR-gyrA hybridization mutation assay (GAMA) and single-strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analyses. The 14 isolates gave seven different SSCP patterns, and LightCycler detected four different mutations. DHPLC detected 11 DNA sequence variants at eight different codons, including those detected by LightCycler or SSCP. One of these mutations was silent. Five isolates contained multiple mutations, and four of these could be distinguished from the composite sequence variants by their DHPLC profile. Seven novel mutations were identified at five different loci not previously described in quinolone-resistant salmonella. DHPLC analysis proved advantageous for the detection of novel and multiple mutations. DHPLC also provides a rapid, high-throughput alternative to LightCycler and SSCP for screening frequently occurring mutations.

Several methods have been reported for the detection of point mutations in bacterial genes including those within the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) region of gyrA (see below); these methods include single-strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) (3, 8, 10) mismatch amplification mutation assay (MAMA)-PCR (13), PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (5, 6), and LightCycler-based PCR-hybridization mutation assay (7, 12). These techniques have also been reviewed in detail (2, 4). These methods rely upon mutation-specific oligoprimers (MAMA-PCR), mutation-specific oligonucleotide probes (LightCycler), and mutation-specific enzymes (PCR-RFLP) that do not detect other sequence variations. SSCP can be used to detect novel mutations, but it relies heavily on differential separation of DNA by electrophoresis that may not always distinguish between polymorphisms. No single method can be used for novel mutation detection with complete confidence, other than sequencing each PCR amplimer, which is expensive. A rapid, high-throughput screening method for detecting novel mutations is required to genotype mutations in genes that confer antibiotic resistance.

Resistance to quinolones in Salmonella enterica is chromosomal in origin and is typically caused by mutations in gyrA that result in amino acid substitutions in the GyrA subunit of DNA gyrase (9). A mutation in the gene encoding the A subunit of topoisomerase IV (parC) has been reported only recently [H. Hansen, W. Rabsch, and P. Heisig, J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47(Suppl. 1):37, abstr. P80, 2001]. Other mechanisms, such as a decrease in drug permeability and active efflux mechanisms, can also contribute to quinolone resistance (9). Point mutations in gyrA associated with resistance to nalidixic acid and decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin are found within the QRDR that includes amino acids 67 to 122 (9).

Here we show that denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography is a rapid method for the detection of mutations within the gyrA gene from different serovars of S. enterica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and antibiotic susceptibility tests.

The MIC of each agent was determined on solid media by the agar doubling dilution procedure prior to this study (1). All 203 isolates of S. enterica selected for this work were resistant to nalidixic acid and had decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of DHPLC, LightCycler, and SSCP methods for mutation detection in gyrA QRDR from Salmonella

| Strain | Serovar | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

Mutation found by method:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAL | CIP | Sequencing | DHPLC | SSCP | LightCycler | ||

| NCTC 74 | Typhimurium | 2 | 0.008 | None (wild type) | None (wild type) | Pattern I | None (wild type) |

| L378 | Typhimurium | 256 | 2 | TCC→TTC Ser83-Phe | Ser83-Phe | Pattern II | Ser83-Phe |

| L575 | Typhimurium | >128 | 1.0 | TCC→TTC Ser83-Phe | Ser83-Phe | Pattern II | Ser83-Phe |

| L400 | Senftenberg | 256 | 2 | GAC→GGC Asp72-Gly | Asp72-Gly | ||

| TCC→TTC Ser83-Phe | Ser83-Phe | Pattern II | Ser83-Phe | ||||

| GCA→TCA Ala119-Ser | Ala119-Ser | ||||||

| L522 | Senftenberg | 256 | 0.5 | TCC→TTC Ser83-Phe | Ser83-Phe | Pattern II | Ser83-Phe |

| GAA→GCA Glu139-Ala | Glu139-Ala | ||||||

| L471 | Fischerkietz | 256 | 1 | TCC→TAC Ser83-Tyr | Ser83-Tyr | Pattern III | Ser83-Tyr |

| L607 | Fischerkietz | 256 | 0.5 | TCC→TAC Ser83-Tyr | Ser83-Tyr | Pattern III | Ser83-Tyr |

| L537 | Newport | 256 | 0.5 | TCC→TAC Ser83-Tyr | Ser83-Tyr | Pattern III | Ser83-Tyr |

| GCC→GCG Ala131-Ala | |||||||

| L574 | Typhimurium | 128 | 0.25 | GAT→AAT Asp82-Asn | Asp82-Asn | Pattern IV | None (wild type) |

| L21 | Virchow | 512 | 0.12 | GAC→GGC Asp87-Gly | Asp87-Gly | Pattern V | Asp87-Gly |

| L24 | Senftenberg | 256 | 0.12 | GAC→GGC Asp87-Gly | Asp87-Gly | Pattern V | Asp87-Gly |

| GAT→GAC Asp144-Asp | Asp144-Asp | ||||||

| L90 | Saintpaul | 512 | 0.25 | GAC→TAC Asp87-Tyr | Asp87-Tyr | Pattern VI | Asp87-? |

| L469 | Fischerkietz | 256 | 2 | GAC→GGC Asp87-Gly | Asp87-Gly | Pattern V | Asp87-Gly |

| GCC→GGC Ala131-Gly | Ala131-Gly | ||||||

| L4 | Typhimurium | >256 | 0.12 | GCA→GAA Ala119-Glu | Ala119-Glu | Pattern VII | None (wild type) |

NAL, nalidixic acid, CIP, ciprofloxacin.

DNA isolation and PCR amplification.

Bacteria were cultured overnight in Lennox broth at 37°C and harvested for subsequent isolation of DNA using DNAace spin cell culture kits (Bioline). PCR was used to amplify the QRDR from gyrA (EMBL accession number X78977) using primers stgyrA1 5′-CGTTGGTGACGTAATCGGTA-3′ (forward) and stgyrA2 5′-CCGTACCGTCATAGTTATCC-3′ (reverse); these primers cover the nucleotides from codon Val70 to Thr152 with an amplimer size of 251 bp. Primers were synthesized by MWG Biotech, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom.

Typical reaction mixtures (50 μl) contained PCR Master Mix (1.5 mM MgCl2) (ABgene), 0.5 μg of DNA, and 250 nM (each) primer. DNA was amplified using a Techne thermal cycler as follows: (i) an initial denaturing step of 10 min at 95°C; (ii) 30 cycles of PCR, with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 52°C, and 30 s at 72°C; and (iii) a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were checked for purity by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer containing 10 μg of ethidium bromide per liter. Products were then quantified by Gene Tools software (Syngene).

DHPLC analysis.

DHPLC was performed with the Wave DNA fragment analysis system (Transgenomic Inc.) which employs a combination of temperature-dependent denaturation of DNA and ion pair chromatography. Briefly, DNA specifically amplified from the test strain is mixed with that amplified from the wild-type strain. The amplimers are denatured simultaneously in the same reaction mixture and then allowed to slowly reanneal. Thus, four species of duplex DNA can form. Heteroduplexes will result in double-stranded DNA containing a mismatch bubble at the point mutation site. Under the nondenaturing conditions (∼51°C) used to separate DNA fragments, all four duplexes will have the same retention time during ion pair chromatography. As the temperature increases to 54 to 63°C (dependent on DNA sequence), the heteroduplex DNA fragments start to denature in the region on either side of the mismatched bases and begin to emerge ahead of the still intact homoduplexes. It is this combination of ion exchange and partial denaturation that forms the basis of DHPLC. Temperature-dependent resolution of homo- and heteroduplexes occurs and can range from full separation of all four duplex species to a single peak with a shift in retention time dependent upon analysis temperature (Transgenomic application note 101, Transgenomic, Inc.). These changes in elution profile are indicative of mutations in the DNA. Subtle differences in elution profile were confirmed by overlay of the profiles in question using WAVEMAKER software. This was particularly important for the recognition of multiple mutations.

PCR products (5 μg) were mixed with an equal amount of DNA amplified from a wild-type standard. DNA mixtures were hybridized to form heteroduplexes by heating to 95°C (4 min) and then cooled gradually by ramping the temperature down to 35°C in 1°C/min steps. The WAVEMAKER utility software was used to determine the correct partial denaturation temperature for mutation scanning based on the sequence of the wild-type DNA from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium NCTC 74.

Duplex products were analyzed using the Wave Nucleic Acid fragment analysis system. Duplex DNA (5 μg) was loaded on the DNASepCartridge (Transgenomics) in 54% eluent A-46% eluent B. The gradient for separation was a 4-min linear gradient from 51% eluent B to 59% eluent B. The flow rate was 0.9 ml min−1. Eluent A contained 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate (TEAA), and eluent B contained 0.1 M TEAA in 25% (vol/vol) acetonitrile. The column was subsequently washed in 100% eluent B for 30 s and then reequilibrated with 54% eluent A-46% eluent B. DNA fragment elution profiles were captured online and visually displayed using Transgenomic WAVEMAKER software.

DHPLC analysis was initially performed at 61°C (the predicted average melting temperature over the whole 251-bp gyrA fragment was 62°C) and then at 63°C to optimize mutation detection at the 3′ region.

Twelve consecutive analyses of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium NCTC 74 wild-type DNA were performed to test the reproducibility of retention times (data not shown). The retention time for DNA from this strain at 61°C was between 5.603 and 5.683 min. Profiles with identical shapes by eye but with a shift in retention time greater than this range were assumed to indicate the presence of different heteroduplexes and DNA sequenced.

Detection of gyrA mutations using LightCycler GAMA.

The region of DNA encompassing the nucleotides between codons 71 and 102 of gyrA was amplified, fluorescently labeled with Sybr green 1 (SG1), and hybridized to the fluorescence-labeled (cyanine 5 [Cy5]), mutation-specific oligonucleotide probe as described previously (12). Hybridization of the probe to the target DNA resulted in an increase in Cy5 fluorescence due to fluorescence resonance energy transfer between Sybr green 1 and Cy5. When the specific mutation was not present, the mismatches between the probe and the target gave a decrease in fluorescence at a lower melting temperature than for a hybrid where there were no mismatches. gyrA hybridization mutation assay (GAMA) reactions were performed in a LightCycler instrument (Roche Diagnostics Ltd.). The detection of mutations was achieved by melting analysis of the oligonucleotide probe and the PCR amplicon immediately after the amplification protocol using probes specific for the substitutions Ser83-Phe, Ser83-Tyr, Asp87-Gly, Asp87-Asn, and Asp87-Tyr (4). Probes were tested in order of the prevalence of the mutation in S. enterica.

SSCP.

SSCP analysis of the PCR products obtained using primers stgyrA1 and stgyrA2 was used as previously described previously (3). Denatured DNA (5 μg) was loaded on to a CleanGel 48S polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis. DNA was stained using PlusOne silver staining kit (AP Biotech).

DNA sequencing and nucleotide sequence analysis.

PCR products required for sequencing were cleaned using Qiaquick PCR purification Kits (Qiagen). PCR product (5 ng) was used as template for TaqCycle Sequencing using ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator version 3.0 cycle sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems). Cycle sequencing products were subsequently analyzed on ABI PRISM 3700 DNA analyzer (Functional Genomics Laboratory, University of Birmingham). The DNA sequences of the QRDR of gyrA from nalidixic acid- and ciprofloxacin-sensitive S. enterica serovars Seftenberg, Fischerkietz, Newport, Virchow, and Saintpaul were determined to confirm their identity to that of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium NCTC 74.

RESULTS

Selection of strains.

DHPLC analyses of the 203 nalidixic acid- and ciprofloxacin-resistant strains showed that 138 contained mutations within the region of gyrA amplified. Thirty-eight percent (n = 77) of these strains contained mutations at codon Ser83. Strains containing each type of single mutation or multiple combinations of gyrA mutation and the wild type (n = 14) were chosen as representative examples for this study.

Mutation detection by DHPLC analysis.

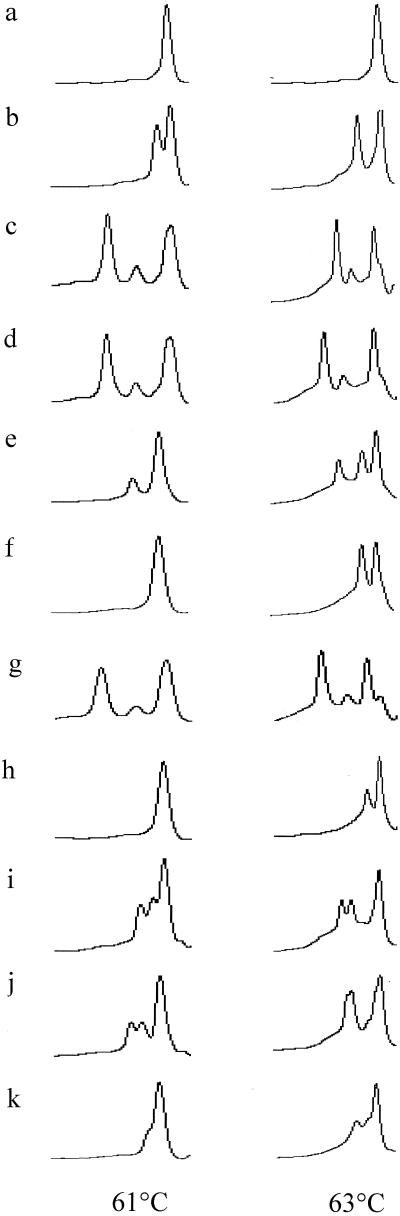

The QRDR amplified from gyrA from nalidixic acid- and ciprofloxacin-sensitive strains of Salmonella serovars Senftenberg, Fischerkietz, Newport, Virchow, and Saintpaul were sequenced and shown to be identical to the equivalent region of gyrA in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium wild-type strain NCTC 74. The amplimer from the control strain NCTC 74 was mixed with each test amplimer for mutation detection analysis by DHPLC. DHPLC analyses were done at both 61 and 63°C to optimize mutation detection over the whole region of the DNA. Any change from the single-peak profile characteristic of wild-type NCTC 74 (Fig. 1a) indicated formation of heteroduplexes and therefore at least one mutation within the test DNA fragment.

FIG. 1.

DHPLC analyses of S. enterica strains at 61 and 63°C. The DHPLC profiles of S. enterica strains (mutations shown in parentheses) are shown in panels a to k as follows: a, NCTC 74 (wild type); b, L378 and L575 (Ser83-Phe); c, L400 (Asp72-Gly, Ser83-Phe, and Ala119-Ser); d, L522 (Ser83-Phe and Glu139-Ala); e, L471, L607 (Ser83-Tyr), and L537 (Ser83-Tyr and Ala131-Ala); f, L21 (Asp87-Gly); g, L24 (Asp87-Gly and Asp144-Asp); h, L469 (Asp87-Gly and Ala131-Gly); i, L90 (Asp87-Tyr); j, L574 (Asp82-Asn); k, L4 (Ala119-Glu).

DHPLC detected 11 different profiles including the wild type. All samples containing the same single-base substitutions had identical profiles (shown by overlaying them using the WAVEMAKER software). Single mutations at the same point but which incorporated a different substitution were easily seen as different DHPLC profiles, for example, L575 (Ser83-Phe) (Fig. 1b) and L471 (Ser83-Tyr) (Fig. 1e). Four of the strains harboring multiple mutations had profiles that were different from their composite single mutations. These were confirmed by analyses at two temperatures where a different profile (L4690) (Fig. 1h) or shift in retention time (L522) (Fig. 1d) indicated the presence of different heteroduplexes. DHPLC analysis was both sensitive and reproducible, with even small shifts in retention times (accurate to 0.08 min) indicating possible mutations.

Seven novel mutations were identified at five different loci not previously described in quinolone-resistant salmonella. These novel mutations were located within the QRDR at codons Asp72, Asp82, and Ala119. Novel mutations outside the QRDR but within the region of DNA amplified were at codons Ala131, Glu139, and Asp144.

The DHPLC profiles from each representative strain are shown in Fig. 1, and the mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing in Table 1. Strains L378, L575, L400, and L522 contained changes in codon 83 resulting in a Ser→Phe substitution. Three different profiles were seen for these strains, indicating the presence of different heteroduplexes formed with NCTC 74 DNA. L378 and L575 share the identical profiles (confirmed by overlay of profiles) at both 61 and 63°C that proved characteristic of a Ser83-Phe substitution (Fig. 1b). L400 (Fig. 1c) and L522 (Fig. 1d) share the same type of profile at 61°C that is different to that of a single Ser83-Phe substitution. This was also true at 63°C, but when the profiles of L400 and L522 were overlaid using WAVEMAKER software, the heteroduplexes from L522 eluted earlier by 0.1 min, indicating they were different from L400. DNA sequencing confirmed that L400 and L522 contained multiple mutations at different loci (Table 1). Strains L471, L607, and L537 all shared the same profile (Fig. 1e) and contained mutations at codon Ser83 encoding a substitution to a tyrosine residue. Three peaks were seen at 63°C compared to two at 61°C. The additional mutation in L537 at Ala131 could not be resolved at these temperatures, presumably because the Ala131 mutation was towards the end of the test DNA fragment or a different analysis temperature is required for optimal mutation detection at this point. The Ser83-Phe profile (Fig. 1b) was quite different from the Ser83-Tyr profile (Fig. 1e).

L21 contains an Asp→Gly substitution at codon 87. It could not be differentiated from the wild type at 61°C but resolved into two peaks at 63°C (Fig. 1f) which is the optimum predicted melting temperature for this region. Strain L24 contains an additional silent substitution at Asp144-Asp (Fig. 1g), the L24 profile was different again from the single Asp87-Asn mutation in L21. L90 (Fig. 1i) and L469 (Fig. 1h) both contain a substitution at codon 87, but L469 has a further substitution at Ala131-Gly and consequently, the profile is different to that of L90. L4, which contains a single substitution at codon 119 nearer the 3′ region of the DNA fragment, was better resolved at 63°C than at 61°C (Fig. 1k). L574 (Fig. 1j) contains a novel substitution at Asp82-Asn that is resolved at both 61 and 63°C.

Mutation detection by LightCycler GAMA analysis.

All strains were tested for gyrA mutations between codons 82 and 88 by LightCycler GAMA using probes for the commonly found mutations Ser83-Phe, Ser83-Tyr, Asp87-Asn, Asp87-Gly, and Asp87-Tyr. Four types of mutation were found with these specific probes. A substitution at Asp87 in strain L90 was suggested by its melting curve but could not be confirmed using the three Asp87 probes. The Asp87-Tyr probe used recognized the TAT codon for tyrosine. DNA sequencing confirmed the mutation to be the TAC codon for the tyrosine substitution (Table 1). LightCycler GAMA analysis therefore requires several analyses using probes for each degenerate codon to confirm less-frequent mutations.

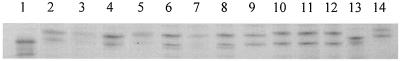

Mutation detection by SSCP analysis.

The DNA amplified from all 14 strains, including the wild type, were analyzed for SSCP. Seven different patterns were detected by SSCP (Fig. 2). NCTC 74 shows wild-type pattern I. Patterns II, III, V, VI, and VII are characteristic of Ser83-Phe, Ser83-Tyr, Asp87-Gly, Asp87-Tyr, and Ala119-Glu substitutions, respectively. Pattern IV indicated a novel mutation that was confirmed as Asp82-Asn by DNA sequencing (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

SSCP analysis of S. enterica strains. Lane 1, NCTC 74 (wild type); lane 2, L400 (pattern II); lane 3, L575 (pattern II); lane 4, L522 (pattern II); lane 5, L378 (pattern II); lane 6, L471 (pattern III); lane 7, L607 (pattern III); lane 8, L537 (pattern III); lane 9, L574 (pattern IV); lane 10, L21 (pattern V); lane 11, L24 (pattern V); lane 12, L469 (pattern V); lane 13, L90 (pattern VI); lane 14, L4 (pattern VII).

Mutation detection by direct DNA sequencing analysis.

DHPLC analyses of 138 strains showed that all the strains contained mutations within the region of gyrA amplified. Thirty-eight percent of these strains contained mutations at codon Ser83. Strains containing each type of single gyrA mutation or multiple combinations of gyrA mutations were chosen as representative examples for this study. The gyrA QRDR regions amplified from each test strain were used as templates for sequencing in both directions. These same PCR amplimers had been previously used in DHPLC and SSCP analyses (see below). The 14 isolates were shown to contain 12 different types of gyrA mutation (Table 1). Seven strains contained substitutions at the frequently documented Ser83 codon. Seven substitutions were located within aspartic acid codons Asp72, Asp82, Asp87, and Asp144 (silent mutation). Mutations at Asp82 have not been reported previously for S. enterica but have been identified in Escherichia coli. Four substitutions were found in alanine codons at Ala119 and Ala131; one of the mutations in Ala131 was silent. A novel mutation outside the QRDR was recognized at Glu139. Five isolates contained more than one base substitution within the region amplified.

DISCUSSION

DHPLC has been used to analyze gene mutations linked to cancer in human cells (11), and a preliminary report also applied this technology to the analysis of gyrA and grlA in isolates of Staphylococcus aureus (F. H. M'Zali, P. M. H. Hawkey, M. H. Wilcox, N. Todd, and G. Tillotson, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1604, 2001). In the present study, DHPLC was thoroughly evaluated as a rapid screening and identification method for DNA sequence variation detection in the QRDR of gyrA from Salmonella serovars and compared with data from LightCycler GAMA and SSCP analyses. In the 14 isolates chosen for this comparative study, DHPLC detected 11 sequence variants at eight different codons including those detected by LightCycler (four types of mutation) or SSCP (seven different patterns, of which two were novel). Novel mutations outside the QRDR but within the region of DNA amplified were at codons Ala131, Glu139, and Asp144. The contribution of these mutations to quinolone resistance needs to be investigated. One of these mutations (Asp144) was silent. Five strains were confirmed to contain multiple mutations by sequencing; four of these strains could be distinguished from the composite sequence variants by their DHPLC profile. SSCP or LightCycler GAMA found no multiple mutations. DHPLC analysis proved advantageous for the detection of novel and multiple mutations, although the recognition of more than three mutations or mutations towards the end of the DNA fragment may be limited. DHPLC also provided a rapid, high-throughput alternative to LightCycler and SSCP for screening frequently occurring mutations. The temperature-dependent, ion pair chromatography required only a 7-min gradient per sample. Automation using a 96-well plate that can be programmed for repeated injections, for analysis at more than one temperature, allowed high throughput with minimal operator time, making it cost-effective. The reproducibility of retention times was accurate to 0.08 min. The WAVEMAKER utility software was used for rapid data analysis by both overlay of profiles (to confirm subtle changes in profile) and detailed peak data. This allowed immediate recognition of identical profiles and those that were novel.

MAMA-PCR has also been used as a rapid method for detecting specific mutations within a short (21-bp) region of Campylobacter jejuni (13); however, speed is compromised by the need for analysis using combinations of several different probes. As with the GAMA method, this technique is limited to detecting known sequence variants.

GAMA requires individual oligonucleotide probes directed against the specific mutation including degenerate codons. Strains containing DNA that is homologous to the probes can be distinguished from those containing different mutations by their probe target melting temperatures. Probes are employed sequentially in order of mutation prevalence (Ser83-Phe is the first choice for salmonella) (7). LightCycler GAMA cannot confirm novel mutations because it is dependent upon specific probes but can suggest probe-DNA mismatches by a change in the melting curve profile. This technique frequently requires multiple oligonucleotide assays on each sample to determine their genotype. DNA samples that are mismatched to the probes must be sequenced. DHPLC requires one assay for each sample, and mutations are indicated simply by a shift in retention time or the characteristic separation of homoduplex and heteroduplex peaks.

The PCR product size is one of the critical factors in resolving denatured single-strand DNA, affecting the sensitivity and specificity of the SSCP technique (2). Pattern shifts associated with mutations close to the end regions of the DNA are also difficult to visualize by SSCP. The mutation at Glu139 in strain L522 was not seen as a conformational change by SSCP but was recognized as a shift in retention time and change in profile by DHPLC. The DHPLC WAVEMAKER utility software was able to predict melting temperatures throughout the length of DNA being analyzed, allowing optimization of mutation detection in specific regions of the amplimer. Mutations in several regions of the DNA were detected from one test sample. Further refinement of the run conditions may yield more dramatic shifts in elution profiles and detect mutations such as Ala131 in strain L469.

Although GAMA and SSCP detected the most common mutations described to date, the prevalence of previously undescribed mutations was not highlighted. This DHPLC method has extended our library of mutations within the QRDR of gyrA in quinolone-resistant S. enterica. DNA sequencing remains the “gold standard” for identifying mutations within the QRDR of gyrA (and other antibiotic resistance-conferring genes) and has recently become faster and more cost-effective. However, screening all topoisomerase genes (gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE) from several hundred clinical isolates is still very costly. DHPLC provides a high-throughput method for detecting both previously documented mutations, multiple mutations, and novel mutations at the same time. The initial cost of the Transgenomic Wave DHPLC is offset by the accurate and high throughput of gyrA analysis that requires less operator time than the established PCR-based methods of SSCP and LightCycler GAMA. As a library of mutation standards is compiled, sequencing will be limited to the novel mutations. Our current work uses DHPLC to identify mutations in gyrB, parC, and parE, so that any relationship between MIC and specific mutations can be identified. Furthermore, large numbers of isolates will allow the prevalence of mutations in each gene to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Department of Environment, Farms and Rural Affairs (formerly The Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food) for project grants OD2004 and VM02100 to L.J.V.P. and M.J.W.

We thank Anthony Jones, The Functional Genomics Laboratory, University of Birmingham, for DNA sequencing and all at Transgenomic, Crewe, United Kingdom for technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, J. M. 2001. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48(Suppl. 1):5-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cockerill, F. R., III. 1999. Genetic methods for assessing antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:199-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Everett, M. J., Y. F. Jin, V. Ricci, and L. J. V. Piddock. 1996. Contributions of individual mechanisms to fluoroquinolone resistance in 36 Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2380-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fluit, A. C., M. R. Visser, and F.-J. Schmitz. 2001. Molecular detection of antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:836-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giraud, E., A. Brisabois, J. L. Martel, and E. Chaslus-Dancla. 1999. Comparative studies of mutations in animal isolates and experimental in vitro- and in vivo-selected mutants of Salmonella spp. suggest a counterselection of highly fluoroquinolone-resistant strains in the field. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2131-2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griggs, D. J., K. Gensberg, and L. J. V. Piddock. 1996. Mutations in gyrA gene of quinolone-resistant salmonella serotypes isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1009-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liebana, E., C. Clouting, C. Cassar, R. Walker, E. J. Threlfall, F. Clifton-Hadley, and R. Davies. 2002. Comparison of gyrA mutations, cyclohexane resistance, and the presence of class I integrons in Salmonella enterica from farm animals in England and Wales. J. Clin Microbiol. 40:1481-1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oubdesselam, S., D. C. Hooper, J. Tankovic, and C. J. Soussy. 1995. Detection of gyrA and gyrB mutations in quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli by single-strand conformational polymorphism analysis and determination of levels of resistance conferred by two different single gyrA mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1667-1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piddock, L. J. V. 2002. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella serovars isolated from humans and food animals. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piddock, L. J. V., V. Ricci, I. McLaren, and D. J. Griggs. 1998. Role of mutations in the gyrA and parC genes of 196 nalidixic acid-resistant salmonella serotypes isolated from animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:635-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tindall, D. J., H. Drabkin, R. Gemmill, W. Franklin, P. Yang, Y. Sugio, and D. L. Smith. 1998. RPTEN/MMAC1 mutations identified in small cell, but not in non-small cell lung cancers. Oncogene 17:475-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker, R. A., N. Saunders, A. J. Lawson, E. A. Lindsay, M. Dassama, L. R. Ward, M. J. Woodward, R. H. Davies, E. Liebana, and E. J. Threlfall. 2001. Use of the LightCycler gyrA mutation assay for the rapid identification of mutations conferring decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in multiresistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1443-1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zirnstein, G., L. Helsel, Y. Li, B. Swaminathan, and J. Besser. 2000. Characterisation of gyrA mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter coli by DNA sequence analysis and MAMA PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]