Indian doctors have questioned the ethics of a study in which patients with severe mental illness were given placebo for up to three weeks in eight hospitals across India.

In the double blind, placebo controlled study, which was carried out in 2001, 144 patients received placebo as part of an effort to evaluate the efficacy of the antipsychotic drug risperidone in patients with acute mania.

Hospital ethics committees had approved the study, which was supported by Johnson & Johnson, and doctors had obtained written informed consent from the patients or their legal representatives. The company and the principal investigators of the study have said that only patients whose symptoms were poorly controlled with standard treatment were admitted to the study.

The study found that patients who were given risperidone showed significantly greater improvements than the patients in the placebo group (British Journal of Psychiatry 2005;187: 229-34).

“The study has helped establish the safety and efficacy of risperidone over and above placebo,” said Sumant Khanna, a psychiatrist who was one of the principal investigators and who worked at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences in Bangalore during the study.

However, the study has now generated a debate on the use of placebo in psychopharmacological studies. The patients were assigned to risperidone or to placebo after a “washout” and screening period lasting up to three days.

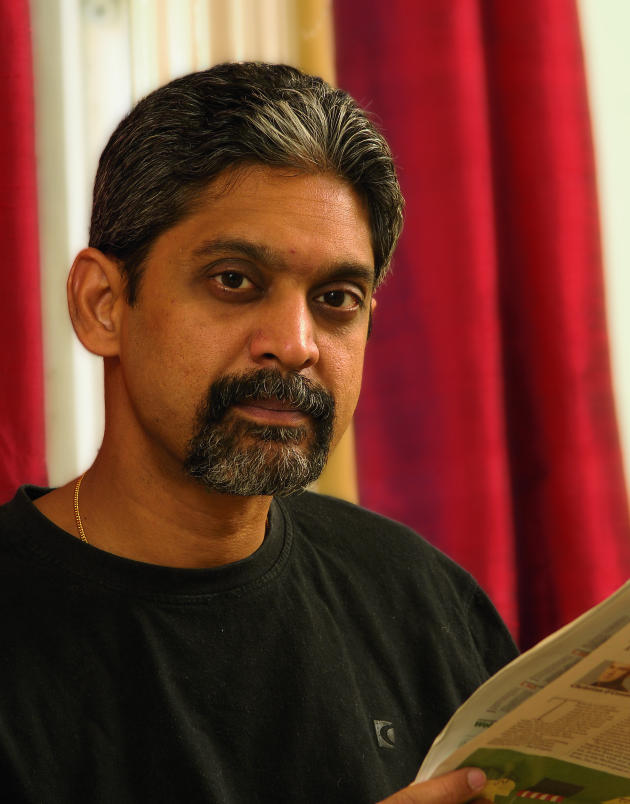

“This study raises important ethical issues,” said Vikram Patel—a psychiatrist and reader in international mental health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and a member of the editorial board of the British Journal of Psychiatry—referring to a commentary he wrote on the subject that was published last week (Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 2006;3: 11-12).

In his commentary Dr Patel argued that the ethical principle requires that participants in a trial's control arm must receive what is the usual, evidence based care under the circumstances.

The study's principal investigators said that a placebo study was justified because a significant proportion of patients with acute mania improve with no treatment. “It's important to show that a new drug against acute mania is better than placebo,” one of the investigators told the BMJ.

Figure 1.

Dr Vikram Patel: “This study raises important ethical issues”

Credit: MARK THOMAS

In a statement to the BMJ, Johnson & Johnson said that the placebo controlled study was “one of a number of similar studies that were conducted in the United States, Canada, many countries throughout Europe, and the rest of the world, including India” and was “carried out in accordance with local and international guidelines, including national and international guidelines for good clinical practice, and [in compliance] with the requirements outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.”

The company emphasised that its “foremost commitment” was “always to the patients who take our medicines, including those who choose to participate in clinical trials that evaluate the safety and effectiveness of new medicines in development. We categorically reject the implication that a clinical trial conducted in India of the same design that was used throughout the rest of the world is medically inferior or ethically questionable.”

The company added that “the placebo controlled design was required to satisfy the requirements of regulatory authorities to allow their evaluation of the risk/benefit of the drug” in compliance with good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study investigators have also said that the patients were constantly monitored in the hospitals and that their wellbeing was paramount throughout the study.

“The study was specially designed to keep patients from any harm,” said Jitendra Trivedi, one of the study's investigators and a psychiatrist at the King George Medical College in Lucknow.

“We chose patients with care. Only patients not likely to harm themselves or others were admitted to the study,” said Vijay Debsikdar, director of a participating hospital in Miraj, in Maharashtra.

Some psychiatrists have expressed concern over the validity of the informed consent obtained from vulnerable patients who participated in the study.

Dr Khanna insists that informed consent was duly obtained. “We used consent forms in different languages. Patients and their family members understood the study very well before they agreed to participate,” he said.

Johnson & Johnson added in its statement to the BMJ: “As a standard rule... subjects or their legal representatives provided written informed consent prior to entry into this study, in each country where the studies were conducted. This was required by the study protocols, and compliance with this requirement was actively monitored by the sponsor of the studies. Capacity to consent is not automatically lost due to psychiatric illness.”

Vasantha Muthuswamy, senior deputy director general and head of the medical ethics division of the Indian Council of Medical Research, who admitted that she was not familiar with the study, observed that “ideally” the sorts of concerns being raised now should have provoked a debate during the approval process.