Abstract

Myostatin is a negative regulator of myogenesis, and inactivation of myostatin leads to heavy muscle growth. Here we have cloned and characterized the bovine myostatin gene promoter. Alignment of the upstream sequences shows that the myostatin promoter is highly conserved during evolution. Sequence analysis of 1.6 kb of the bovine myostatin gene upstream region revealed that it contains 10 E-box motifs (E1 to E10), arranged in three clusters, and a single MEF2 site. Deletion and mutation analysis of the myostatin gene promoter showed that out of three important E boxes (E3, E4, and E6) of the proximal cluster, E6 plays a significant role in the regulation of a reporter gene in C2C12 cells. We also demonstrate by band shift and chromatin immunoprecipitation assay that the E6 E-box motif binds to MyoD in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, cotransfection experiments indicate that among the myogenic regulatory factors, MyoD preferentially up-regulates myostatin promoter activity. Since MyoD expression varies during the myoblast cell cycle, we analyzed the myostatin promoter activity in synchronized myoblasts and quiescent “reserve” cells. Our results suggest that myostatin promoter activity is relatively higher during the G1 phase of the cell cycle, when MyoD expression levels are maximal. However, in the reserve cells, which lack MyoD expression, a significant reduction in the myostatin promoter activity is observed. Taken together, these results suggest that the myostatin gene is a downstream target gene of MyoD. Since the myostatin gene is implicated in controlling G1-to-S progression of myoblasts, MyoD could be triggering myoblast withdrawal from the cell cycle by regulating myostatin gene expression.

Myostatin is a newly identified member of the transforming growth factor β superfamily, and myostatin-null mice have been found to show a two- to threefold increase in skeletal muscle mass due to an increase in the number of muscle fibers (hyperplasia) and the size of the fibers (hypertrophy) (21). Subsequently, we (15) and others (9, 22) reported that Belgian Blue and Piedmontese breeds of cattle, which are characterized by heavy muscling, have mutations in the myostatin gene coding sequence. Hence, myostatin is considered a negative regulator of muscle growth.

Earlier studies have indicated that myostatin gene expression appears to be transcriptionally regulated during development (15, 21). Initially myostatin gene expression is detected in myogenic precursor cells of the myotome compartment of developing somites, and the expression is continued in adult axial and paraxial muscles (21). Different axial and paraxial muscles have been shown to express different levels of myostatin (15). Recent publications have shown that myostatin protein is also detected in heart (33) and mammary gland (14). In addition, myostatin is present in human skeletal muscle, and its expression is increased in the muscles of human immunodeficiency virus-infected men with muscle wasting compared to that in healthy men (8). Recently Wehling et al. (36) have reported higher levels of myostatin mRNA and protein during muscle unloading and a decrease during reloading in fully differentiated muscle. Hence myostatin gene expression appears to be transcriptionally regulated in various physiological conditions.

Myostatin appears to function by controlling myoblast cell cycle progression (35). Recombinant myostatin, when added to actively growing myoblasts, inhibited the progression of G1 myoblasts into S phase. Molecular analysis indicated that myostatin down-regulated the protein levels of Cdk2 and up-regulated the levels of its inhibitor p21, thereby rendering Cdk2 inactive. As a consequence, one of the targets of Cdk2, pRb, is hypophosophorylated, leading to sequestration of the E2F transcription factors, a family of proteins that are essential for G1/S progression. Thus, the hyperplasia condition observed in the absence of myostatin could be due to increased proliferation of myoblasts because of a deregulated G1/S checkpoint (35).

Compared to the biology, little is known about the regulation of the myostatin gene. To study the transcriptional regulation of the myostatin gene, we cloned 10 kb of bovine myostatin gene upstream sequence and analyzed its cis elements and trans-acting factors. Transcriptional regulation of muscle-specific genes is commonly studied by determining the effects of muscle-specific and stage-specific transcription factors on the promoter activity. One of the sequence motifs recognized as a critical regulatory component in muscle gene expression is the E box (CANNTG) (2, 5, 6). Muscle-specific genes such as those for creatine kinase, myosin light chain, and myogenin have multiple E boxes in their enhancers or promoters that act cooperatively to regulate gene transcription (1, 27, 29). E boxes are the binding sites for the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors collectively referred to as myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) (17, 23). The MRFs include the MyoD, Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4 transcription factors (10, 30, 31). MyoD and Myf5 are expressed in myoblasts and myotubes and have been shown to be required for myogenesis. Myogenin mRNA, in comparison, increases significantly as myoblasts commit to differentiate and is thus required for myotube formation. Similarly, MRF4 transcripts are detected after differentiation, suggesting that MRF4 is also critical for the terminal myogenic differentiation events.

Because there are several E boxes in the myostatin gene promoter, we speculated that the muscle-specific expression of the myostatin gene would be in part dependent on the MRFs. In this study, we report that one of the E boxes (E6) appears to be critical for the myostatin promoter activity and that MyoD interacts with this E-box (E6) motif in vitro as well as in vivo. The myostatin promoter activity was higher in the G1 phase of the myoblast cell cycle, which coincides with the high levels of MyoD in G1 phase (16). In the context of the cell cycle, it thus may be possible that MyoD, by regulating the myostatin gene, controls myoblast cell cycle withdrawal and differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of the myostatin gene promoter.

Two kilobases of the genomic sequences immediately upstream of the translation start site of the myostatin gene were obtained by inverse PCR (modified protocol of Pang and Knecht [25]). Briefly, a series of Sau3A1 digests of bovine genomic DNA were carried out. Two micrograms of each digest was separated on a 1% agarose gel, and one partial digest was chosen for further work. The DNA was then ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 1× ligase buffer to a final concentration of 5 ng/μl. The ligation was carried out at 22°C overnight. After phenol and chloroform extractions, the DNA was precipitated and used for PCR. The primers 5′CTGCTCGCTGTTCTCATTCAGATC3′ and 5′ATCCTCAGTAAACTTCGCCTGGA3′ were used for amplification.

PCR was carried out in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 250 ng of religated DNA, a 0.2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), a 0.8 μM concentration of each primer, and 2 μl of Elongase enzyme mix (Gibco-BRL) in 1× B buffer supplied by the manufacturer. PCR was performed for 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 2 min, and 68°C for 6 min. A 2-kb PCR fragment was cloned into the TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced.

Further 5′ upstream regulatory sequences of the bovine myostatin gene were isolated from a bovine lambda DASH II genomic library (Stratagene) by the method of Sambrook et al. (32). The library was screened with the 5′-most 500 bp of 2 kb of genomic DNA isolated by inverse PCR. The genomic clones were subcloned into pBluescript and sequenced.

Construction of myostatin gene promoter-reporter plasmids.

5′ truncations of myostatin gene upstream sequences were PCR amplified as KpnI fragments by using either bovine genomic DNA or lambda bovine genomic clones as a template (Table 1). The sequences of the primer combination are shown in Table 2. The amplification of 6.2 kb of myostatin gene upstream sequence was carried out by using the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche Diagnostics) with following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 68°C for 5 min for 35 cycles. The final extension was at 68°C for 7 min. The PCR conditions for the amplification of 3.5 kb of myostatin gene upstream genomic DNA were 94°C for 20 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min for 35 cycles. For the rest of the fragments, the PCR was performed with Taq polymerase at 94°C for 20 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min for 35 cycles. The amplified PCR products were directly cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and subsequently mobilized into the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega) as KpnI fragments to generate different constructs harboring various 5′ truncations (Table 1). The two internal deletion constructs 1.6ΔSpeI and 0.9ΔSpeI were made by digesting the 1.6 or 0.9 construct with SpeI to delete the region between positions −515 and −673 and then ligating the rest of the plasmid. The plasmids were verified by sequencing and purified with a Maxi Prep kit (Qiagen).

TABLE 1.

5′ DNA sequences from the bovine myostatin gene used to assess gene promoter activitya

| Construct name | Size (bp) | Flanking nucleotides (5′, 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 6.2 | 6,214 | −6081, +133 |

| 3.5 | 3,541 | −3408, +133 |

| 1.6 | 1,592 | −1549, +43 |

| 0.9 | 890 | −847, +43 |

| 0.7 | 701 | −658, +43 |

| 0.4 | 415 | −372, +43 |

| 0.15 | 150 | −107, +43 |

| 1.6ΔSpeI | 1,434 | −1549, +43 |

| 0.9ΔSpeI | 732 | −847, +43 |

Systematic 5′ deletion constructs of the myostatin promoter were generated by cloning PCR DNA fragments into the pGL3-Basic (Promega) vector as Kpn I fragments. The two SpeI deletion constructs were made by restriction of the 1.6 or 0.9 construct with SpeI to eliminate E5 and E6.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in construction of 5′ deletions of the myostatin promotera

| Fragment size (bp) | Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 6,214 | FJ22 | 5′GGGGTACCCCGTGTAATCAGAA CAGTGTTA3′ |

| FJ13 | 5′GGGGTACCGGTTTTAAAATCA ATACAATCT3′ | |

| 3,541 | FJ10 | 5′GGGGTACCAATTCCTGGGAGAA ATTCTCTA3′ |

| FJ13 | 5′GGGGTACCGGTTTTAAAATCAA TACAATCT3′ | |

| 1,592 | RK55 | 5′GGTACCCAGGGCATCTGGTTTG TGTC3′ |

| RK56 | 5′GGTACCTGCCTGCCCAGTCTGA GAGA3′ | |

| 890 | MS12K | 5′GGTACCCACTGGAAGGCTGA3′ |

| RK56 | 5′GGTACCTGCCTGCCCAGTCTGA GAGA3′ | |

| 701 | MS47 | 5′GGTACCCTGAAATACAATTTTC ATATG3′ |

| RK56 | 5′GGTACCTGCCTGCCCAGTCTGA GAGA3′ | |

| 415 | MS11K | 5′GGTACCCTGAGGGAAAAGCAT ATCAA3′ |

| RK56 | 5′GGTACCTGCCTGCCCAGTCTGA GAGA3′ | |

| 150 | MS10K | 5′GGTACCACCTCTGACAGCGAGA TTC3′ |

| RK56 | 5′GGTACCTGCCTGCCCAGTCTGA GAGA3′ |

The sequences of primers with 5′ flanking KpnI sites used to amplify various 5′ upstream genomic fragments are shown.

Site-directed mutagenesis of various E boxes.

Site-directed mutations in the E boxes E3, E4, and E6 of the proximal cluster in the 1.6-kb myostatin gene promoter were introduced by PCR with the forward oligonucleotides 5′AGAAGTAGTGAAATGAATCAGC3′, 5′CAAATAAAATTATTTTTACTTGAATTCCTTACTTAAATAG3′, and 5′CTTAATACTAGTCCATGGAAACTGAAATAC3′, respectively, to give E3M, E4M, and E6M (the E-box motifs are underlined, and nucleotide changes are in boldface). PCRs were performed in a 50-μl volume containing Pwo polymerase buffer, a 200 nM concentration each of the primer pairs, 0.4 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 3.5 U of Pwo polymerase (Roche Diagnostics). Using the respective mutant primer and the wild-type downstream primer (RK56), 10 cycles were performed. After completion of 10 cycles, 1 μl of 50 μM wild-type upstream primer (RK55) was added and 10 more cycles were performed, and then 1 μM wild-type downstream primer (RK56) was added and 10 more cycles of PCR were done. The conditions for the PCR were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min; an additional 10 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 48°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. After the PCR, A-tailing of the PCR products was carried out using dATP and Taq polymerase. The cloning of the PCR products and the subsequent steps were essentially as described above. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing, and the plasmids were purified with a Maxi Prep kit (Qiagen).

Construction of MyoD, Myf5, and MEF2C expression plasmids.

Murine MyoD, Myf5, and MEF2C were amplified in a combined reverse transcription-PCR. RNA from mouse skeletal muscle was extracted by using Trizol (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized in a 20-μl reverse transcription reaction mixture from 5 μg of total RNA, using a Superscript preamplification kit (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The following primers with flanking BamHI sites were used to amplify MyoD, Myf5, and MEF2C: 5′GGATCCTAAGACGACTCTCAC3′ and 5′GGATCCAGTGCCTACGGTGG3′ (MyoD), 5′GGATCCATGGACATGACGGACGGCT3′ and 5′GGATCCTCAGCTTCAGGGCTTCT3′ (Myf5), and 5′GGATCCGAACGAATGCAGGG3′ and 5′GGATCCTGTGATCATGTTGC3′ (MEF2C).

The PCR conditions were identical for both MyoD and Myf5, that is, 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, except that 10 μl of Q solution (Qiagen) was added for MyoD amplification. For the amplification of MEF2C, the following cycling conditions were used: 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The MyoD (1,047-bp), Myf5 (836-bp), and MEF2C (1,545-bp) fragments thus obtained were directly cloned into a TA cloning vector and subsequently mobilized into phosphatase-treated pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) as BamHI fragments. The plasmid DNAs pJM7 (Myf5), pJM11 (MyoD), and pJM49 (MEF2C) were purified by using a Maxi Prep kit (Qiagen).

Transfections and luciferase assays.

C2C12 cells (37) were routinely cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (D-MEM) (Gibco-BRL), buffered with NaHCO3 (41.9 mmol/liter; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and gaseous CO2. Phenol red (7.22 nmol/liter; Sigma) was used as a pH indicator. Penicillin (105 IU/liter; Sigma), streptomycin (100 mg/liter; Sigma), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%; Gibco-BRL) were routinely added to media. For transfections, C2C12 cells were seeded into 9.6-cm2 plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at a density of 15,000 cells/cm2 in D-MEM containing 10% FBS. After a 24-h attachment period, the cells were transfected with 4 μg of total plasmid DNA (2 μg each of the plasmid DNAs for cotransfection experiments) by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The cultures were then incubated in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C for a further 18 h. Growth medium containing 10% FBS was then removed, and differentiation-promoting medium (D-MEM containing 2% horse serum [Gibco-BRL]) was added. Cultures were then incubated with 5% CO2 at 37°C for a further 48 h. The medium was then removed, and cells were rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and lysed in 300 μl of 1× Reporter lysis buffer (Promega). Lysates were collected and vortexed for 10 s. After a quick freeze-thaw, the lysates were centrifuged at 12,000× g for 15 s and supernatants were analyzed for luciferase reporter gene activity (Promega) in a Turner Designs luminometer (model TD-20/20). The total protein was estimated by the Bio-Rad protein assay. To control for variations in transfection efficiency, the experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated a minimum of three times, with six replicates assayed each time.

To generate a stable cell line that harbors the myostatin promoter-reporter system, the 1.6-kb myostatin gene promoter and luciferase reporter gene were cloned into pcDNA3 as a NotI-XhoI fragment, and 12.5 μg of the DNA was transfected into C2C12 myoblasts as described above. Stably transfected C2C12 cells were selected for their resistance to Geneticin (400 μg/ml).

Western blotting.

Cell extracts (15 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (4 to 12% polyacrylamide) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked in Tris-buffered saline-Tween-5% milk (33) at 4°C overnight and then incubated with the primary antibody. The following dilutions of primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting: myostatin, 1:2,000; MyoD, 1:200 (monoclonal; PharMingen), and Myf5 and MEF2, 1:200 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The blot was washed and incubated with a 1:1,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Dako, Carpinteria, Calif.) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed, and horseradish peroxidase activity was detected using an ECL kit (NEN Life Science Products Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Purification of recombinant MyoD and E47.

Recombinant MyoD and E47 were expressed in Escherichia coli SG13009 containing pQT-MyoD or pQT-E47, kind gifts from Stephen F. Konieczny and Kyung-Sup Kim. Bacteria were grown to mid-log phase, and proteins were induced for 4 h with 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. Pelleted bacteria were resuspended in lysis buffer (Qiagen) and sonicated. The recombinant proteins were purified to homogeneity by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose chromatography according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Qiagen). Purified proteins were separated on by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (4 to 12% polyacrylamide) and stained with Coomassie blue.

Gel mobility shift assays.

The wild-type oligonucleotide (5′CTTAATACTAGTCAATTGAAACTGAAATAC3′) containing the E6 E box and an oligonucleotide (5′CAAATAAAATTATTTTTACTTCAAATGCTTACTTAAATAG3′) containing the E4 E box were labeled with [32P]ATP (NEN) by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Gibco-BRL). 32P-labeled E6 and E4 were then hybridized to their respective complementary strands by heating the oligonucleotides to 95°C for 3 min and then slowly cooling to room temperature. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by chromatography through a Quick Spin column (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Competitor duplexes were made by heating 100 pmol of complementary strands for 3 min at 95°C and allowing the strands to cool slowly to room temperature. The gel mobility shift assays were performed as described previously (18). Recombinant MyoD or E47 and MyoD-E47 heterodimer were incubated with the 32P-labeled probe (70,000 cpm) in a final volume of 20 μl containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 10% glycerol, 75 mM KCl, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 μg of poly(dI-dC), and 0.5% fetal calf serum (FCS). After 20 min of incubation at room temperature, samples were subjected to electrophoresis on a 5% acrylamide gel containing 25 mM Tris base, 25 mM boric acid, and 0.5 mM EDTA at 40 mA at room temperature. For the competition assays, the competitor was added at a 100-fold molar excess.

Gel mobility shift assays were also performed with C2C12 nuclear extracts. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described by Marshall et al. (20). Binding reactions were carried out essentially as described above by incubating labeled oligonucleotides E6 and E4 with 3 μg of nuclear extract and then run on a 5% acrylamide gel. To confirm the presence of MyoD in the retarded complex, nuclear extracts from C2C12 cells were incubated with 1 μl of MyoD antibody (PharMingen) before incubation with the labeled probe.

CHIP assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP) assays were done as described previously by Luo et al. (19). C2C12 cells stably transfected with 1.6 kb of the myostatin promoter were grown in 9.6-cm2 plates. At 48 h after the differentiation medium was added to the cells, formaldehyde was added at 1% to the culture medium and the cells were incubated at room temperature for 10 min with mild shaking. The cells were washed with PBS twice and then resuspended in lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) with Complete proteinase inhibitor (Roche). After a brief sonication, the lysates were cleared by centrifugation. A portion of the lysate was saved as input chromatin. Equal volumes of the lysate were incubated with either anti-MyoD antibody (PharMingen) or control rabbit IgG at 37°C overnight. Immunoprecipitated complexes were collected with protein A-Sepharose beads. The precipitates were sequentially washed with buffer containing 0.01% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mM EDTA, 16.7 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 150 mM NaCl twice, followed by once with the same buffer containing 500 mM NaCl. After the final wash, the complexes were eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS and 0.1 M NaHCO3). Five molar NaCl was added (final concentration, 200 mM), and samples were incubated at 65°C for 3 h to reverse the formaldehyde cross-linking and then treated with proteinase K. Input chromatin was also treated as described above to reverse the formaldehyde cross-linking. DNA was precipitated with ethanol, and the pellet was resuspended in Tris-EDTA. PCR was performed with primers to amplify the region containing the E6 E box. The 5′ primer was 5′CACTGGAAGGCTGAG3′, and the 3′ primer was 5′GTATTTCAGTTTCAATTGACTAGTATTAAG3′. The resulting product was 198 bp and was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Synchronization.

C2C12 cells stably transfected with the 1.6-kb myostatin promoter construct were synchronized as previously described by Kitzmann et al. (16). At 24 h after plating, cells were rinsed twice in PBS, and then D-MEM without methionine supplemented with 1% FCS was added and left for 36 h. Quiescent (G0) myoblasts were allowed to reenter the cell cycle by changing the medium to fresh complete D-MEM containing 10% FCS, and the cells were harvested 4 h after the medium was added for the G1 time point. Cells were also synchronized at the G1/S boundary by adding 1 mM hydroxyurea (Sigma) 1 h after release of methionine deprivation for a total period of 15 h.

Quiescent “reserve cells” were obtained after differentiation of the C2C12 cells stably transfected with the 1.6-kb myostatin promoter construct. On average, 60 to 70% of myoblasts fuse and differentiate, while 30 to 40% of myoblasts stop proliferating but do not differentiate (16). Myotubes were removed by a short trypsinization (0.15%, 15 s), leaving quiescent reserve cells adhered to the culture dish. Cell extracts were made from these cells and assayed for luciferase activity.

Sequence analysis.

Sequence analysis for transcription factor binding sites was done with the MatInspector program (26).

RESULTS

Isolation of bovine myostatin gene upstream clones.

A genomic region of ∼1.6 kb which is immediately 5′ to the translation start codon ATG of the bovine myostatin gene was amplified from bovine genomic DNA by using partial inverse PCR. The PCR-amplified fragment was cloned into the TA cloning vector and sequenced. By using 0.5 kb of the genomic DNA that is 5′-most of this 1.6-kb genomic DNA as a probe, a bovine lambda genomic library was screened to isolate a further ∼8.4 kb of the myostatin gene upstream region. Various overlapping restriction fragments of the genomic DNA from the lambda clones were subcloned into pBluescript vector and analyzed by restriction analysis and sequencing. Using 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA end, we previously have identified the transcription start site of the bovine myostatin gene (13), and position +1 has been assigned to the first transcribed nucleotide in Fig. 1A.

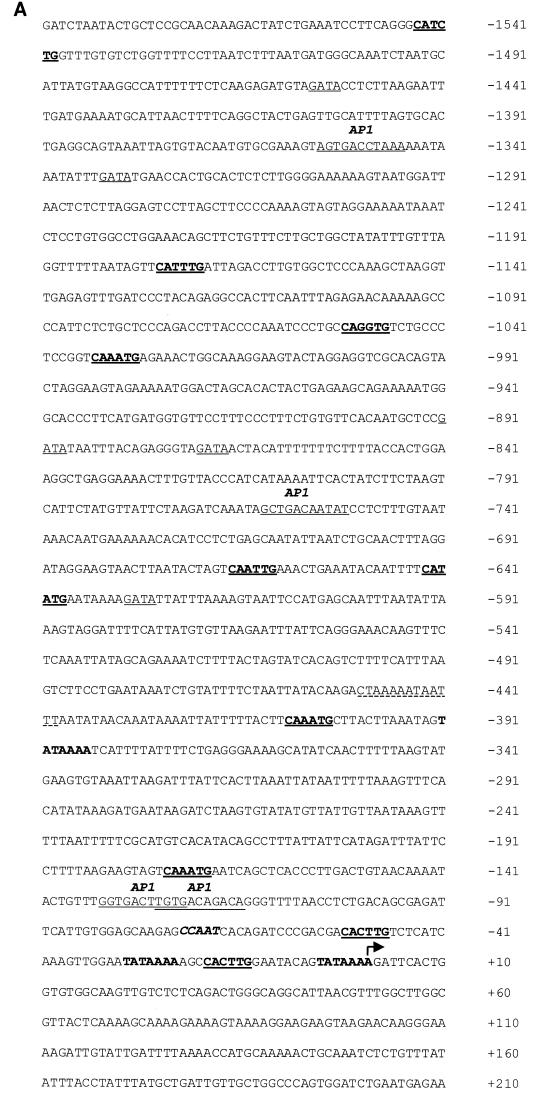

FIG. 1.

(A) Sequence analysis of the −1549 to +43 fragment of the myostatin gene promoter. Of the 10-kb sequence of the bovine myostatin gene upstream region obtained, 1,600 bp is shown here. A bent arrow indicates the transcription start site. Sequence analysis with MatInspector identified several sequences consistent with previously identified muscle-specific transcription factor binding sites and other nuclear factor binding sites. Known TATA boxes are shown in boldface, a CAAT box is italicized, AP-1 sites are underlined and marked, E boxes are boldface and underlined with boldface lines, the MEF2 binding sequence is underlined with a broken line, and GATA boxes are underlined. (B) E-box motifs in the myostatin gene upstream sequences. Approximately 1.6 kb of the myostatin gene upstream regions from cattle, human, pig, and mouse were compared for E-box motifs, which are indicated by boxes.

Transcription factor binding sites in the myostatin gene upstream region.

The DNA sequence of 10 kb of the myostatin gene upstream region was analyzed with Lasergene and MatInspector software for restriction analysis and nuclear factor binding elements. The DNA sequence of ∼1.6 kb with various nuclear factor binding sites which is relevant to this communication is shown in Fig. 1A. Analogous to the case for a typical mammalian basal promoter, we have found one CAAT box (−73 to −69) and three different TATA boxes within 400 bp from the transcriptional start site. MatInspector analysis revealed that there are several different putative binding sites for transcription factors located in myostatin gene upstream sequences (Fig. 1A). These include both muscle-specific transcription factor binding sites and other gene-specific nuclear factor binding sites. Among the muscle-specific transcription factors, a MEF2 binding site is located within 500 bp of the promoter sequence and 10 E boxes are spread within −1.6 kb of upstream sequence. The E boxes present in the myostatin promoter region appear to be arranged in several clusters (Fig. 1B). A cluster of two E boxes (E1 and E2) with an identical sequence of CACTTG is located at −20 and −53, very close to the TATA boxes and the transcription initiation site. Another cluster of four E boxes (E3 to E6) spanning the next 600 bp, designated proximal E boxes, is located at −175, −410, −643, and −667 from the transcription initiation site. The third cluster of distal E boxes (E7 to E10) is located at nucleotides −1034, −1053, −1176, and −1544 within the −1- to −1.6-kb region. The proximal cluster and two E boxes in the distal cluster (E7 and E9) have a consensus sequence of CA A/T T/A TG. On the other hand, the remaining two E boxes in the distal cluster have various sequences of CAGGTG (E8) and CATCTG (E10). In addition, several sequences consistent with binding sites for AP1, GATA, GATA1, GATA2, and GATA3 are also present (Fig. 1A) within the 1.6-kb region.

Conservation of myostatin gene upstream sequences during evolution.

The GenBank database was searched for any matches to the bovine myostatin gene upstream sequence. Three entries containing human (AX058992), porcine (AF093798), and murine (AX139025) myostatin promoter sequences were recovered. Comparison of the 1.6-kb bovine myostatin promoter sequence with either murine, human, or porcine myostatin gene upstream sequence revealed that there is a high degree of homology in the promoter region of the myostatin gene. The similarity between human and bovine myostatin gene upstream regions was found to be 79%, and that between bovine and murine myostatin gene upstream regions was 68%, whereas bovine and porcine myostatin promoter regions were 64% identical (data not shown). We next compared the conservation of E-box clusters among bovine, human, porcine, and murine myostatin gene promoters (Fig. 1B). In approximately 1.6 kb of the human myostatin promoter sequence we identified six E boxes, out of which E-boxes 1, 2, and 3 are conserved in both position and sequence between bovine and human myostatin promoter sequences. In the porcine promoter we detected 15 E boxes within the 1.6-kb region; the first cluster, close to the TATA boxes, has three E boxes instead of two as seen in the bovine and human promoters (Fig. 1B). The proximal cluster of the porcine myostatin promoter has 10 E boxes, and boxes 4, 6, 8, and 9 are at almost the same positions as E3, E4, E5, and E6 of the bovine promoter. The 1.6-kb region of the murine promoter has only five E boxes, and of those, boxes 1, 2, and 3 are conserved with respect to E1, E2, and E3 of the bovine promoter. In addition to the E boxes, the CAAT box and the MEF2 binding site are conserved in the four species mentioned (data not shown).

Myostatin promoter activity in C2C12 cells and fibroblasts.

To determine the regions within the bovine 5′ myostatin genomic DNA that might specify functional promoter activity, upstream genomic DNA up to −1.6, −3.5, and −6.2 kb was subcloned into the pGL3-Basic vector and transfected into C2C12 cells. The reporter gene activity was measured by luciferase assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, DNA fragments that initiated at the 5′ end at −1.6 and −3.5 kb and terminated at +43 and +133 kb (constructs 1.6 and 3.5, respectively) displayed significant reporter gene activity relative to the control vector in C2C12 cells. However when the reporter gene activities of the two fragments were compared to each other, the −3.5-kb construct displayed significantly lower reporter gene activity. The promoter activity further decreased when the 5′ end of the upstream genomic DNA was extended beyond −3.5 kb to −6.2 kb (construct 6.2) (Fig. 2A). These findings indicate that within the 1.6 kb of the upstream genomic DNA, all of the necessary elements to drive the expression of the reporter gene in C2C12 cells are present. Hence, we refer to the genomic sequence spanning nucleotides −1.6 to +43 kb as the promoter of bovine myostatin gene. The same construct was equally active in bovine primary myoblast cultures (data not shown). However, due to the unavailability of transformed bovine myoblast cell lines, we decided to use murine C2C12 cells for the characterization of the promoter. Beyond this −1.6-kb region, one or more repressor elements may be situated between −1.6 and −6.2 kb. In this study we have fine mapped the bovine myostatin promoter and extensively characterized the DNA binding elements required for the muscle-specific expression.

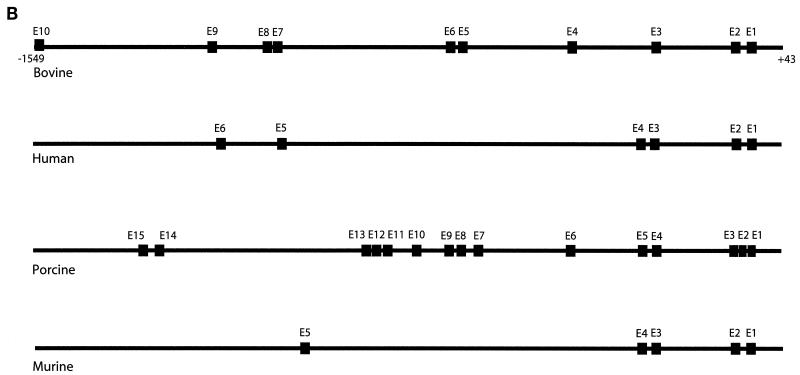

FIG. 2.

(A) Mapping of the bovine myostatin promoter activity in C2C12 cells. Bovine myostatin gene upstream genomic DNA up to 1.6, 3.5, or 6.2 kb (Table 1) was subcloned into the luciferase reporter vector pGL3-Basic and transfected into C2C12 cells. The fold increase in luciferase reporter activity over that of the control vector (pGL3B) was measured 48 h after the differentiation medium was added. The luciferase values were corrected for protein content. Bars represent means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to control vector. (B) Bovine myostatin promoter activity in fibroblasts. The 1.6 construct was transfected into CHO and NIH 3T3 cells, and the luciferase reporter activity was measured. The fold increase in luciferase reporter activity over that of the control vector (pGL3B) was measured 48 h after the differentiation medium was added. The luciferase values were corrected for protein content. Bars represent means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to control vector.

The expression of the myostatin gene during myogenesis is predominantly in skeletal muscle. Thus, to determine the muscle specificity of the myostatin promoter, the 1.6-kb bovine myostatin promoter was also transfected in two fibroblast cell lines, NIH 3T3 and CHO. As shown in the Fig. 2B, three- to fourfold induction of the bovine myostatin promoter was seen in NIH 3T3 and CHO cells, respectively. Bovine promoter activity in the fibroblasts was about four times lower than that in C2C12 cells (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with the muscle-specific nature of myostatin promoter.

Fine mapping of the bovine myostatin promoter.

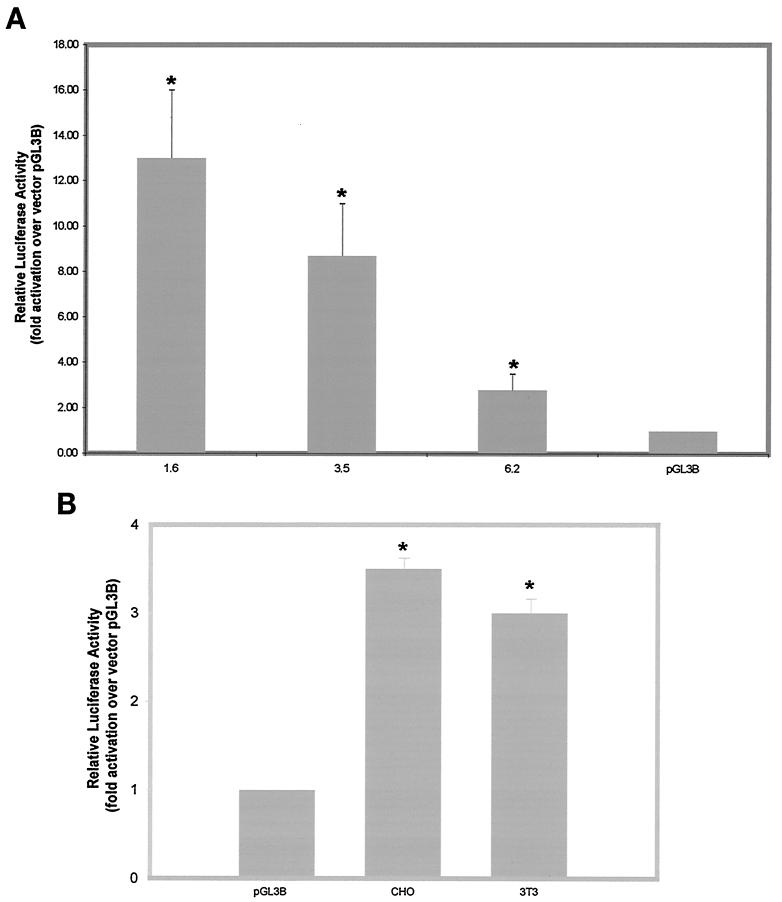

Since 1.6 kb of myostatin gene upstream DNA contains several muscle-specific and other transcription factor binding sites, systematic 5′ deletion analysis was performed to delineate the necessary cis-acting sequences and the E boxes that are essential for the expression of the reporter gene in C2C12 cells. Six different 5′ deletion constructs were made to study the contribution of individual E-box clusters in the regulation of myostatin gene expression. DNA constructs 0.9 and 0.15 lacked either the distal E-box cluster or the distal plus proximal E-box clusters, respectively, while the 0.7 construct contained the E1 to E5 E boxes and the 0.4 construct contained the E1 to E3 E boxes. Two other fragments, 1.6ΔSpeI and 0.9ΔSpeI, have the same internal deletion from position −515 to −673 that eliminates E5 and E6. The above-mentioned DNA fragments were cloned into the pGL3-Basic vector, and the promoter activity was assayed by measuring the luciferase activity. Analysis of the reporter gene activity indicated that there was a 15-fold increase in the reporter gene activity compared to that of the control when C2C12 cells were transfected with the vector containing 1.6 kb of myostatin promoter (Fig. 3). When C2C12 cells were transfected with the 0.9 construct (which lacks the distal E-box cluster), no change in myostatin promoter activity compared to that of the 1.6 construct was noted. These results indicate that the proximal E-box cluster is sufficient to drive the reporter gene activity in C2C12 cells. Hence, we then deleted individual or two or three closely located E boxes of the proximal cluster and assessed myostatin promoter activity. An internal deletion of only two closely situated E boxes (E5 and E6) in the proximal cluster, with the distal cluster intact, significantly lowered the myostatin promoter activation, from 15-to 9-fold, implying that those two E boxes may be important. However the myostatin promoter activity was further reduced to sixfold when the distal cluster was also absent along with E5 and E6 (0.9ΔSpeI), indicating that the distal cluster of E boxes could compensate for the trans activity of E5 and E6 (Fig. 3). The results in Fig. 3 show that for construct 0.7, in which only the E6 E box of the proximal cluster is deleted, the promoter activity was reduced to sixfold. This is a substantial reduction compared to the activity of the 0.9 construct (16-fold). These results suggest an important role for the E6 E box in myostatin promoter regulation. The induction of the luciferase reporter gene by the 0.4 construct was six- to sevenfold, and when the cells were transfected with the 0.15 construct (which lacks both proximal and distal E-box clusters) containing only E1, E2,and TATA elements, three- to fourfold induction of the luciferase activity was noted. In conclusion, the sequence elements contained in the 1.6-kb fragment are required for promoter activity, and one of the proximal E boxes (E6) is critical for the maximal activity of the 1.6-kb promoter.

FIG. 3.

Deletion analysis of the myostatin gene 1.6-kb upstream region. A series of 5′ deletion fragments and two SpeI internal deletion fragments were cloned into the luciferase reporter vector pGL3-Basic and tested for expression in C2C12 cells. The fold increase of luciferase reporter activity over that of the control vector (pGL3B) was measured 48 h after the differentiation medium was added. The luciferase values were corrected for protein content. Bars indicate means ± standard deviations for six replicates. Positions of various E-box motifs (E1 to E10) and SpeI restriction sites are indicated. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to control vector.

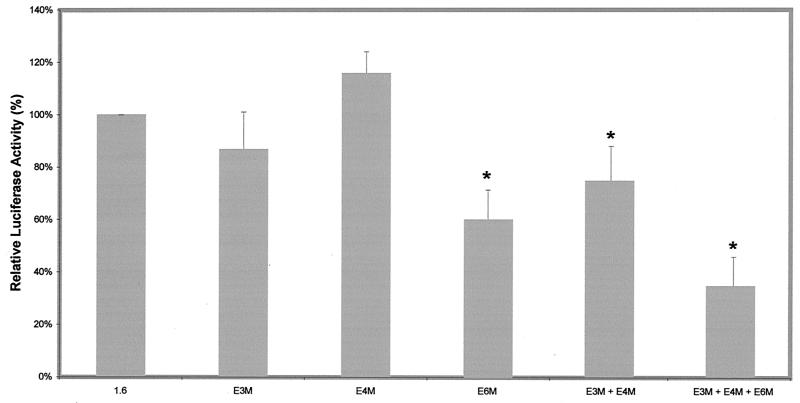

Mutational analysis of the E boxes in the myostatin promoter.

Our data have established that the proximal E-box cluster is sufficient to drive the expression of the reporter gene in C2C12 cells. We then focused on delineating the contributions of individual E boxes in the proximal cluster to the muscle-specific regulation of myostatin promoter activity. For this reason we performed site-directed mutagenesis to mutate either a specific individual E box (E3M, E4M, and E6M) or a combination thereof (E3M+E4M and E3M+E4M+E6M) and subcloned them into the pGL3-Basic vector. Mutation of an individual E box (E3M or E4M) did not affect the reporter luciferase activity significantly (Fig. 4); however, mutation of E6M alone decreased the promoter activity to 60%. Mutation of both E3 and E4 (E3M+E4M) reduced the activity to 75% of the wild-type activity. Mutation of one more E box (E6) in the same construct (E3M+E4M+E6M) further decreased the activity from 75 to 35% of the wild-type promoter activity. These results provide further confirmation that E6 is crucial for myostatin promoter activity. Thus, we infer that within the proximal E-box cluster, E6 is the major MRF binding site and can compensate for the loss of other E boxes, including E3 and E4.

FIG. 4.

Mutational analysis of E-box motifs in the proximal cluster of the bovine myostatin promoter. Mutations in the individual E-box motifs (E3M, E4M, or E6M) or combinations thereof (E3M+E4M and E3M+E4M+E6M) were generated by PCR, and the promoter fragments containing the mutations were cloned into the reporter vector pGL3-Basic. The percentage of luciferase activity was derived by comparing the luciferase activity of each mutant construct with that of the 1.6 construct. The activity of the 1.6 construct is represented as 100%. Bars indicate means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to the 1.6 construct.

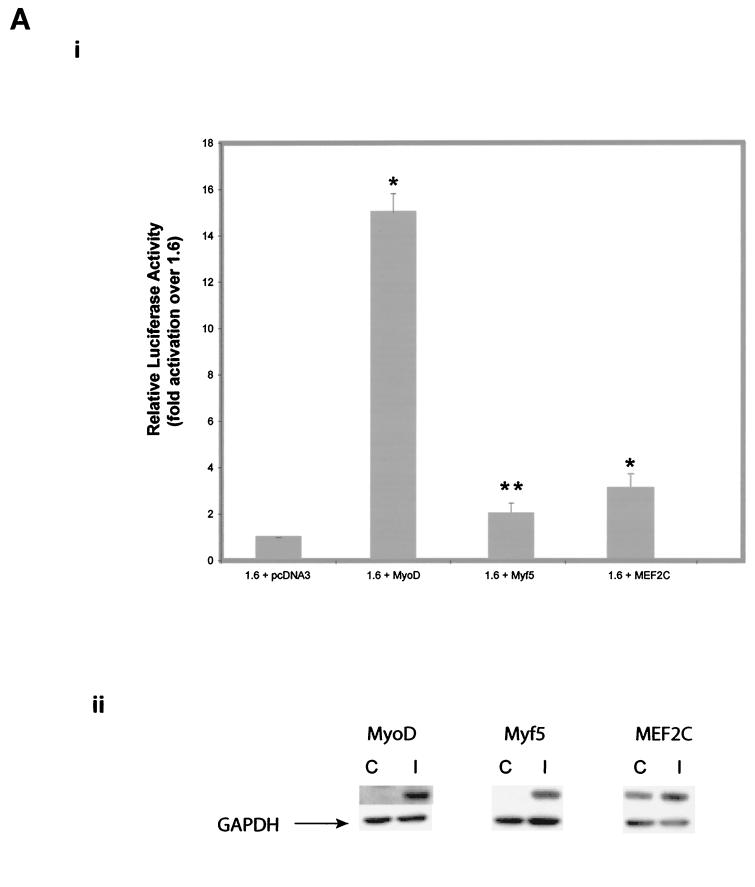

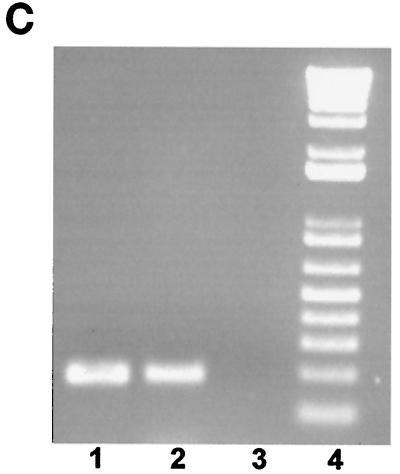

Myf5, MyoD, and MEF2 transactivate the myostatin promoter.

The results described above indicate that the myostatin promoter contains a cluster of MRF binding sites (E boxes) and that mutating proximal E boxes (E3, E4, and E6) in combination, or deletion of E6, results in a significant reduction of myostatin promoter activity. Since E boxes have been shown to bind to relevant MRFs such as MyoD and Myf5, we studied the role of these muscle-specific transcription factors in the regulation of the myostatin gene. Furthermore, earlier studies have shown that myostatin mRNA is present very early (day 10.5 postcoitum) in myogenesis in the dermomyotome compartment of somites in mice. This overlaps with the expression of both muscle-specific MRFs, Myf5 and MyoD (E8 and E9.75), in the dermomyotome (4, 7, 24, 34). Hence to investigate if the myostatin gene is the downstream target of MRFs, we cotransfected the 1.6-kb myostatin promoter construct with either MyoD or Myf5 in C2C12 cells and assessed the myostatin promoter activity by luciferase reporter assay. The results show that both MyoD and Myf5 induced the activation of the myostatin promoter (Fig. 5A, panel i). About a 15-fold increase in the myostatin promoter activity was noted when the 1.6 construct was cotransfected with MyoD. When the same myostatin promoter construct was cotransfected with Myf5, the promoter activity increased by only twofold. Western analysis confirmed the ectopic expression of both MyoD and Myf5 in C2C12 cells (Fig. 5A, panel ii). Hence, it appears that MyoD preferentially regulates myostatin promoter activity.

FIG. 5.

A. Stimulation of the myostatin promoter activity by MyoD, Myf5, and MEF2C. Panel i, murine MyoD, Myf5, and MEF2C were cloned in the expression vector pcDNA3. Two micrograms each of MyoD, Myf5, MEF2C, or pcDNA3 was cotransfected with 2 μg of the 1.6 construct. Fold stimulation of myostatin promoter activity by MyoD (1.6 + MyoD), Myf5 (1.6 + Myf5), or MEF2C (1.6 + MEF2C) over that by the 1.6 construct in pcDNA3 is shown. Maximal stimulation (15-fold) of the myostatin promoter was observed with MyoD, while Myf5 and MEF2C stimulated by only 2- and 3-fold, respectively. Bars indicate means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to the 1.6 construct; ∗∗, P < 0.05 compared to the 1.6 construct. Panel ii, Western blot analysis showing the ectopic expression of MyoD, Myf5, and MEF2C. Protein extracts from MyoD-, Myf5-, and MEF2C-transfected cells (lanes I) and vector-transfected cells (lanes C) were separated on SDS-4 to 12% gradient polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Western analysis was performed with the respective antibodies. GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was used as a protein loading control. (B) Stimulation of the myostatin promoter by MyoD in NIH 3T3 cells. Panel i, two micrograms of MyoD expression vector or pcDNA3 was cotransfected with the 1.6 construct. Fold stimulation of myostatin promoter activity by MyoD is shown. Bars indicate means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to the 1.6 construct. Panel ii, Western analysis showing the induction of endogenous myostatin by MyoD in C2C12 and 3T3 cells. Western analysis was performed with myostatin-specific antibodies on protein extracts from C2C12 and 3T3 cells that were transfected with MyoD expression vector (lanes I) or control vector (lanes C). Myostatin and GAPDH (protein loading control) bands are indicated. Panel iii, optical density values for endogenous myostatin protein in the Western blots shown in panel ii.

In addition to the E boxes, the upstream sequence of the bovine myostatin promoter also contains a single MEF2 binding site at position −451, indicating that MEF2 might be involved in myostatin gene regulation. Hence to investigate the effect of MEF2 on myostatin gene expression, C2C12 cells were cotransfected with the 1.6 myostatin promoter construct and the MEF2C expression construct, and the luciferase activity was assayed. The results show that MEF2C enhanced the myostatin promoter activity by threefold (Fig. 5A, panel i) indicating that MEF2C can transactivate the myostatin promoter in C2C12 cells. Western analysis confirmed the ectopic expression of MEF2C (Fig. 5A, panel ii). To further prove that the myostatin promoter is specifically regulated by MyoD, we cotransfected 1.6 kb of the myostatin promoter with the MyoD expression construct in NIH 3T3 cells. As shown in Fig. 5B, panel i, MyoD up-regulated myostatin promoter activity by sixfold in these fibroblasts. If MyoD was inducing the myostatin promoter activity, we reasoned that upon ectopic expression of MyoD, the endogenous levels of myostatin protein should also increase. In order to confirm this, protein extracts from MyoD-transfected C2C12 and NIH 3T3 cells were subjected to Western blot analysis. The results of the Western analysis suggest that MyoD induced the endogenous myostatin levels in C2C12 cells (Fig. 5B, panels ii and iii). However, MyoD-mediated induction of endogenous myostatin levels in the fibroblasts was marginal (Fig. 5B, panels ii and iii).

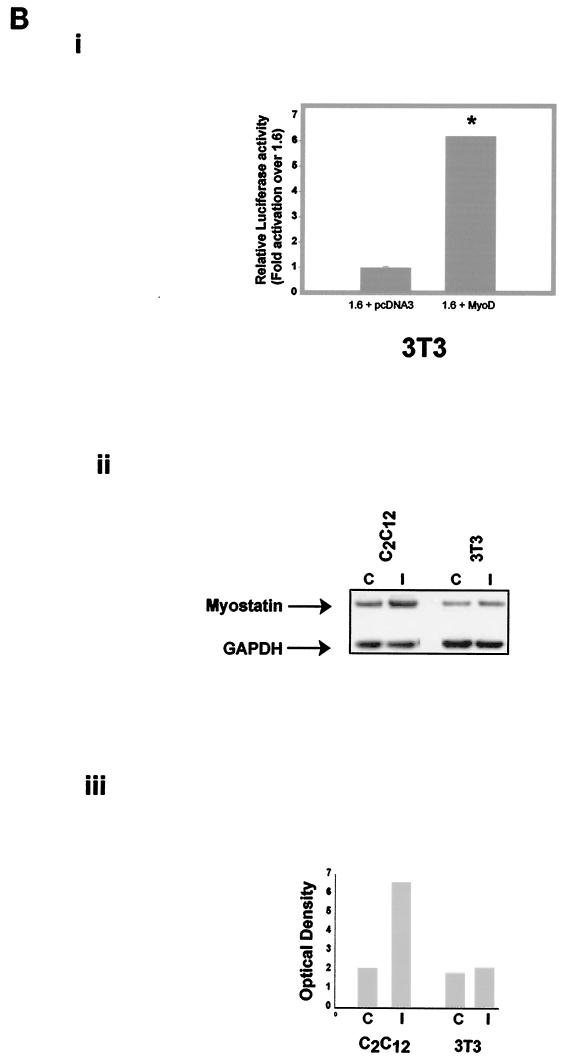

In order to study the role of the E boxes in MyoD responsiveness, we introduced site-specific mutations in the E boxes of the proximal cluster, i.e., E3, E4, and E6, and cotransfected them with MyoD. Mutating either E3 or E4 individually reduced the myostatin promoter activity to ∼80% of that of the 1.6 construct activated by MyoD. However, mutating E6 alone reduced the promoter activity to ∼60% of that of the 1.6 construct activated by MyoD (Fig. 6A). The combined mutations of either E3+E4 or E3+E4+E6 decreased the responsiveness significantly and reduced the transactivation of the myostatin promoter by MyoD to 32 and 11%, respectively. Furthermore, the effects of E-box mutations were additive, since the most significant decrease was seen with the triple mutant (Fig. 6A). These results were further supported by 5′ deletion analysis. Both the 1.6ΔSpeI and 0.9ΔSpeI constructs displayed about a 60% decrease in transactivation by MyoD compared to the 1.6 construct (Fig. 6B). The responsiveness of the 0.7 construct was further reduced to 31%, suggesting that E6 of the proximal cluster may be a major MRF response element (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

(A) The proximal E-box motifs are required for stimulation by MyoD. The wild-type 1.6 promoter construct or E-box mutant constructs (as described in the Fig. 4 legend) were cotransfected with MyoD, and the percent stimulation of the luciferase activity of each construct by MyoD is shown. The activity of the 1.6 construct cotransfected with MyoD is represented as 100%. Bars indicate means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to the 1.6 construct; ∗∗, P < 0.05 compared to the 1.6 construct. (B) The E6 E-box motif is crucial for MyoD stimulation of the myostatin promoter. The 1.6 construct or 5′ deletions (0.9 and 0.7) or internal deletions (0.9ΔSpeI and 1.6ΔSpeI) thereof were cotransfected with MyoD, and the percent stimulation of luciferase activity by MyoD is shown. The activity of the 1.6 construct cotransfected with MyoD is represented as 100%. Bars indicate means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to the 1.6 construct.

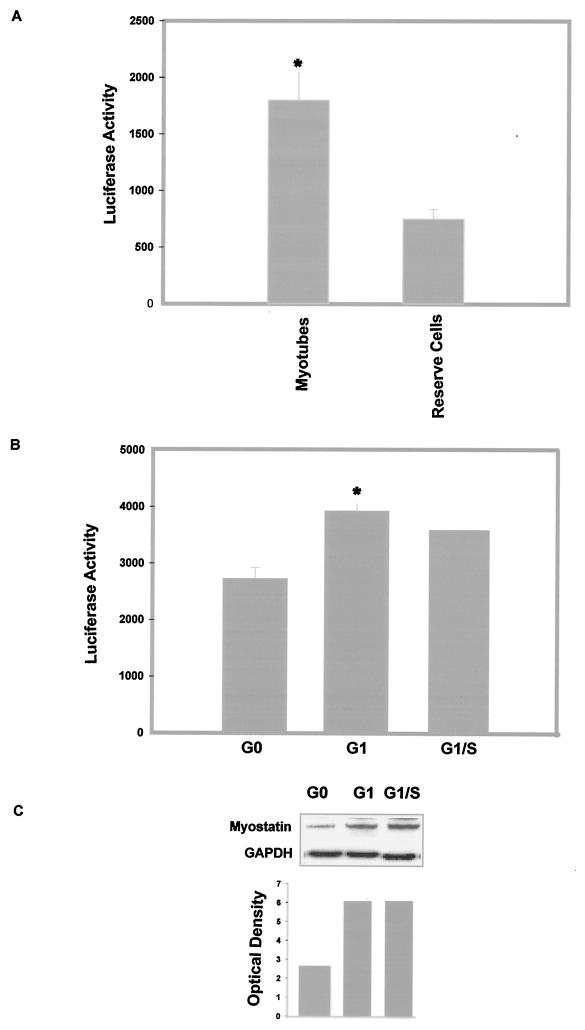

MyoD binds to the E6 E box both in vitro and in vivo.

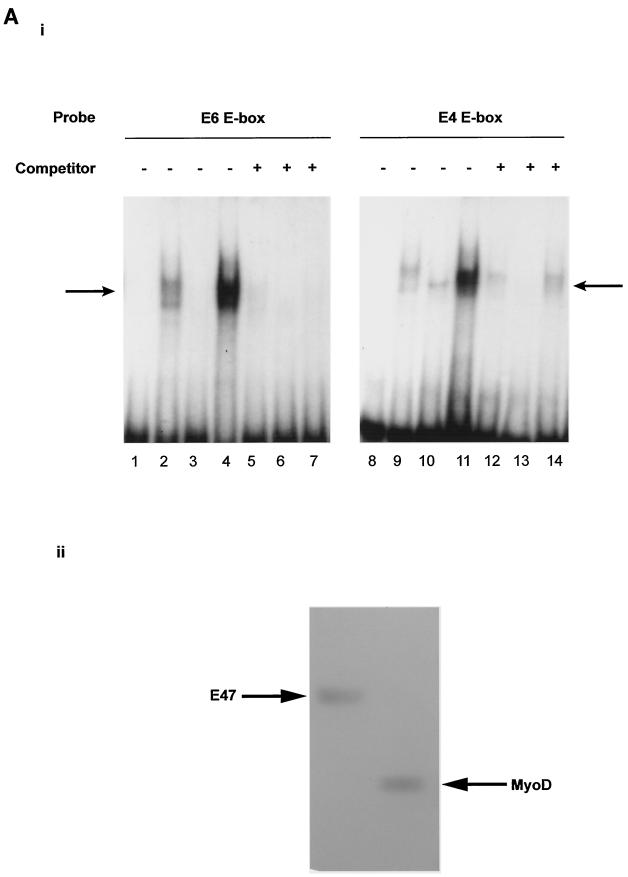

Our results demonstrate that MyoD transactivates the myostatin promoter and that certain E boxes are utilized for this transactivation. To confirm MyoD binding to the E boxes in vitro, we performed gel shift analysis. Although in vitro MyoD homodimers can bind to E boxes, in vivo MyoD functions as a heterodimer with E proteins such as E12 and E47 (17). MyoD and E47 were expressed and purified from E. coli, and the homogeneity of the purified proteins is shown in Fig. 7A, panel ii. Oligonucleotides containing the E6 or E4 E box were radiolabled and incubated with purified MyoD, E47, or MyoD and E47 together. As shown in Fig. 7A, panel i, the mobility of the probes was retarded weakly by MyoD alone (lanes 2 and 9), suggesting that MyoD can bind as a homodimer. A strong shift in the electrophoretic mobility of the E6 and E4 probes was seen when both MyoD and E47 were present together and formed a heterodimer (lanes 4 and 11). In comparison to E4, the E6 probe shows relatively stronger binding to MyoD (lanes 2, 4, 9, and 11). The retarded complex was also competed out by a 100-fold molar excess of cold E6 or E4 self-competitor, indicating that the retarded band includes the E-box motif. Thus, both the E4 and E6 E boxes bind MyoD and E47; however, with the E6 probe relatively more MyoD-E47-DNA complex was observed than with the E4 probe.

FIG. 7.

(A) Panel i, gel mobility shift assay of the E boxes in the myostatin promoter. A 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing the wild-type E6 E box or E4 E box, as described in Materials and Methods, was incubated with purified MyoD (500 ng), E47 (80 ng), or MyoD (500 ng)-E47 (80 ng) heterodimer. Protein-DNA complexes (arrows) were resolved on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. Lanes 1 and 8, control; lanes 2 and 9, MyoD; lanes 3 and 10, E47; lanes 4 and 11, MyoD-E47. The shifted complexes were competed by a 100-fold molar excess amount of unlabeled competitor E6 or E4. Lanes 5 and 12, MyoD and self competitor; lanes 6 and 13, E47 and self competitor; lanes 7 and 14, MyoD-E47 and self competitor. Panel ii, SDS-polyacrylamide gel showing the purified recombinant MyoD and E47 proteins. Two micrograms of purified recombinant MyoD and E47 proteins (arrows) was separated on an SDS-4 to 12% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (B) Gel mobility shift assay of the E boxes (E6 and E4) with C2C12 nuclear extracts. A 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing the wild-type E6 E box or E4 E box was incubated with 3 μg of nuclear extract prepared from actively growing or differentiating C2C12 cells for 24 and 48 h. Protein-DNA complexes are indicated by an arrow. Self competitor was present in lanes 4, 5, 6, 14, 15, and 16. In lanes 7, 8, and 9, nuclear extracts from C2C12 cells were preincubated with antibodies to MyoD before being incubated with the labeled oligonucleotide. (C) CHIP analysis. The 198-bp myostatin promoter fragment containing the E6 E box was amplified from input chromatin, immunoprecipitated chromatin with MyoD antibody, or control antibody. Lane 1, input chromatin; lane 2, anti-MyoD antibodies; lane 3, control IgG; lane 4, DNA ladder.

To determine whether endogenous MyoD binds to the E6 E box, the band shifts were also performed using C2C12 nuclear extracts. Since MyoD expression and activity are induced upon myogenic differentiation, the reactions were carried out by incubating labeled E6 or E4 probe with nuclear extracts made from actively growing myoblasts or differentiating myotubes at 24 or 48 h after the differentiation medium was added. In the presence of myotube extracts, the retarded complex could be seen at both 24 and 48 h (Fig. 7B, lanes 2, 3, 12, and 13). While this retarded complex was quite prominent in the presence of myotube extracts (lanes 2, 3, 12, and 13), it was very weak in the presence of actively growing myoblast extracts (lanes 1 and 11). In addition, the retarded complex was competed out by excess amounts of E6 and E4 competitors, suggesting that the retarded complex is specific to an E box. Once again the intensity of the retarded complex of the E4 probe was lower than that of E6. The presence of MyoD in the retarded complex was confirmed by preincubating the nuclear extracts with antibodies to MyoD. The results show that antibodies to MyoD block the formation of the protein DNA complex (Fig. 7B, lanes 7, 8 and 9).

To determine whether MyoD binds to E6 in vivo, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay using anti MyoD antibodies. For these experiments, C2C12 cells stably transfected with the 1.6-kb myostatin promoter construct were used, and the fragmented chromatin was subjected to immunoprecipitation with MyoD-specific antibodies. Nonspecific rabbit IgG was used as a negative control. When input chromatin or immunoprecipitated chromatin was subjected to PCR with primers spanning E6, a 198-bp band was specifically detected in the amplicons (Fig. 7C, lanes 1 and 2) and was absent in the antibody control (lane 3), confirming that E-box E6 is occupied by MyoD in vivo.

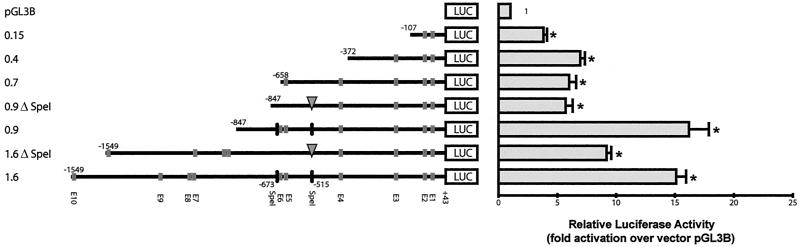

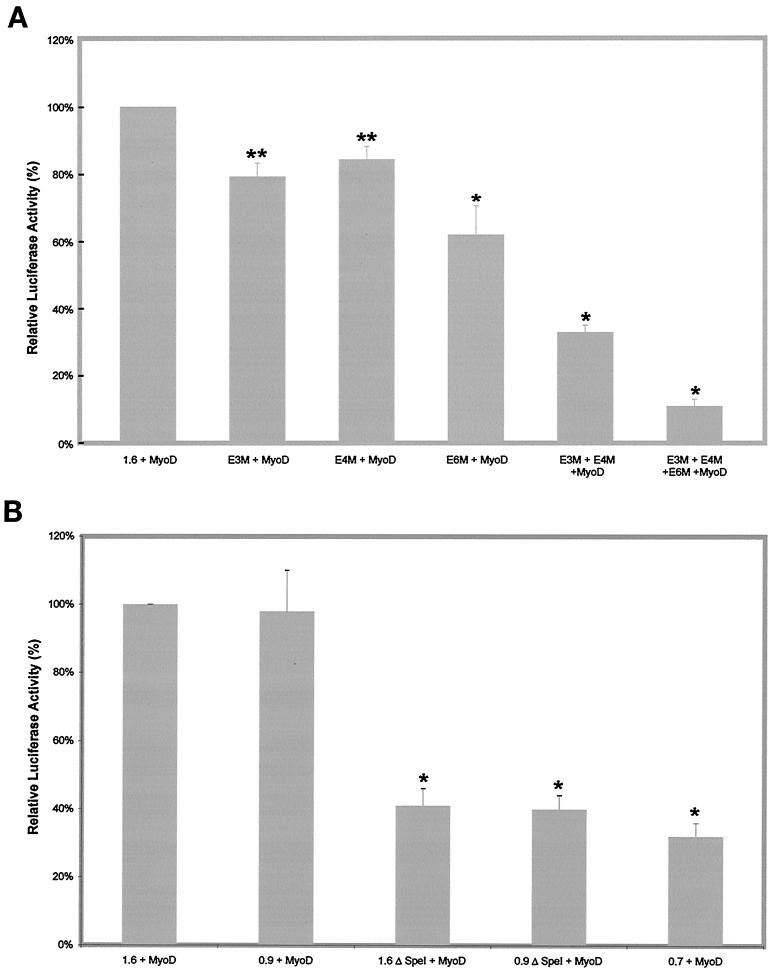

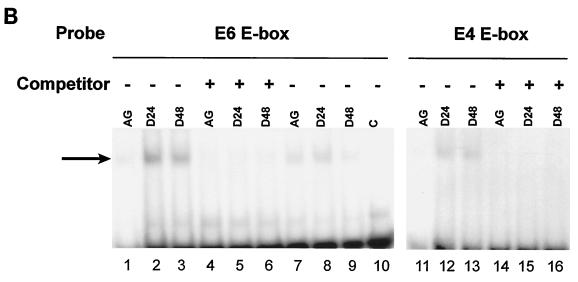

Myostatin promoter activity is down-regulated in reserve cells.

When switched to low-serum medium (2% horse serum), C2C12 myoblasts start to differentiate and represent a heterogeneous population of cells. In addition to the multinucleated differentiated cells, myotube cultures contain mononucleated, quiescent so-called reserve cells (16, 38). The reserve cells are molecularly different from the differentiated myotubes. While the myotubes have relatively high levels of MyoD and low levels of Myf5, the reserve cells express high levels of Myf5 and no MyoD (16, 38). Since myostatin gene expression appears to be regulated by MyoD, we chose to investigate the myostatin promoter activity in reserve cells. For this purpose, C2C12 cells that were stably transfected with 1.6 kb of the myostatin promoter were allowed to differentiate and then subjected to limited trypsinization to separate myotubes and reserve cells. Stable integration of a bovine myostatin promoter reporter construct in C2C12 did not affect the ratio of myotubes to reserve cells (data not shown). We then determined the expression of luciferase reporter activity of the 1.6-kb myostatin promoter construct in the reserve cells and myotubes. The results show that there was a ∼65% decrease in the myostatin promoter activity in the reserve cells compared to the differentiated myotubes (Fig. 8A).

FIG. 8.

Myostatin promoter activity in differentiated myotubes and reserve cells. (A) C2C12 cells stably transfected with the 1.6-kb construct were allowed to differentiate and then subjected to limited trypsinization to separate the myotubes and the reserve cells. The luciferase activity was determined and normalized to the total protein. Bars indicate means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to reserve cell luciferase activity. (B) Myostatin promoter activity fluctuates during the cell cycle of myoblasts. C2C12 cells stably transfected with the 1.6-kb construct were synchronized in a precise phase of their cell cycle. Luciferase reporter activity was assayed at G0, G1, and G1/S phases of the cell cycle and normalized to the total protein. Three independent experiments were performed. Bars indicate means ± standard deviations for six replicates. ∗, P < 0.001 compared to G0. (C) Western analysis of endogenous myostatin levels during the myoblast cell cycle. Endogenous levels of myostatin detected by antimyostatin antibodies during G0, G1, and G1/S phase of the cell cycle are shown. Optical density values corresponding to the Western blot analysis are also shown. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Cell cycle dependence of myostatin promoter activity.

The MRFs, such as MyoD and Myf5, regulate cell cycle withdrawal and induction of differentiation in myoblasts. A recent analysis of MyoD and Myf5 expression during the cell cycle in synchronized myoblasts revealed contrasting profiles of expression (16). MyoD is absent in G0, peaks in mid-G1, falls to its minimum levels at G1/S, and rises from S to M. Our unpublished preliminary immunocytochemistry results also indicate that asynchronized C2C12 myoblasts show varying degrees of myostatin immunoreacivity. Thus, we evaluated myostatin promoter activity during the myoblast cell cycle. C2C12 cells, which stably express luciferase under control of the 1.6-kb myostatin promoter, were synchronized, and the luciferase reporter activity as well as the expression of endogenous myostatin was analyzed over the course of the cell cycle. Luciferase assay revealed that the myostatin promoter activity was higher in G1 than in G0 or at the G1/S boundary (Fig. 8B). The Western blot results also confirm the up-regulation of myostatin levels during G1 compared to G0 (Fig. 8C). These results indicate that the transcription of the myostatin gene increased during G1, which coincides with the peak expression of MyoD.

DISCUSSION

Myostatin is a member of the transforming growth factor β superfamily, and it is well established that the myostatin gene negatively regulates muscle growth by controlling myoblast cell cycle progression (35). Although the biological role and mechanism of myostatin function are being unraveled, at present the regulation of myostatin gene expression is not known. In this communication, we show that myostatin gene upstream regulatory elements are well conserved during evolution and that the muscle-specific transcription factors, such as MyoD, regulate myostatin gene expression during myoblast growth and differentiation.

A comparison of myostatin promoter sequences from various chordates reveals that the necessary promoter elements that regulate the muscle-specific expression are situated within 2 kb of the upstream sequences. One of the striking features of the myostatin promoter is the presence of clusters of E boxes, and some of these E boxes are conserved in position as well as in sequence in different species. Thus, preservation of developmental and tissue-specific expression of the myostatin gene in mice, cattle, and pigs (14, 15, 21) can be attributed to the functional conservation of the myostatin promoter.

Analysis of the myostatin promoter indicates that the activity of the myostatin promoter is higher in muscle cells, such as C2C12 cells, than in nonmuscle cells, such as NIH 3T3 and CHO cells (Fig. 2). This is not surprising given the fact that predominant expression of myostatin is observed in the skeletal muscle, although low-level expression is seen in heart and mammary glands (14, 33). Muscle-specific expression of myostatin appears to be regulated by MRFs and MEF2C. While MEF2C and Myf5 are weak activators, MyoD appears to be a potent activator in both muscle and nonmuscle cells (Fig. 5). This demonstrates that during myogenesis, myostatin is a downstream target of MyoD. MyoD regulates its target genes by binding to an E-box element in the enhancer region (1, 2, 5). Sequence analysis indicates that the bovine myostatin promoter region contains 10 E-box motifs, of which the distal cluster is dispensable for the maximum promoter activity (Fig. 3). In the proximal E-box cluster, the MRF-mediated transcription appears to be mainly through the E6 E box, even though the two other proximal E boxes (E3 and E4) are also important (Fig. 3). The following evidence strongly supports that the E6 E box is a critical regulatory element for myostatin promoter activity. First, 5′ deletion analysis showed that the proximal region containing E6 is necessary to confer activity to the myostatin promoter (Fig. 3). Second, mutation of E6 leads to about a 40% reduction in the myostatin promoter activity (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the same E box is also essential for activated transcription by MyoD (Fig. 6A). The gel shift results also suggest that binding of MyoD to the E6 E box is stronger than that to the E4 E box (Fig. 7A, panel i, and B). The results of the CHIP assay further confirm that MyoD is recruited to the E6 E box in vivo (Fig. 7C).

Based on the above-described experimental evidence and the following circumstantial evidence, it can be suggested that MyoD could be regulating myostatin during muscle growth. For example, like MyoD, myostatin is preferentially expressed in fast fibers. MyoD has been shown to be present in adult fast glycolytic fibers and is involved in the maintenance of the fast IIB/IIX fiber type (11, 12). Similarly higher levels of myostatin have been seen in the fast glycolytic fibers of cattle (3), pig (14), rat (36), and fish (28). Also, during early myogenesis, myostatin expression coincides with that of MyoD, with maximal expression of both MyoD and myostatin at day 90 of gestation in cattle.

Since MyoD appears to regulate myostatin gene expression, we assessed myostatin promoter activity under conditions where C2C12 cells express altered levels of MyoD. It is well established that differentiating myotubes express higher levels of MyoD, which subsequently activates terminal differentiation-specific markers. However, in actively growing myoblasts there are relatively lower levels of MyoD, which is biologically inactive. We thus performed band shift analysis using nuclear extracts made from proliferating myoblasts and differentiating myotubes to determine if we could detect an increase in the MyoD-E-box complexes from nuclear extracts made from differentiating myotubes. The results (Fig. 7B) indeed suggest that there is an increase in the retarded complex when nuclear extract from differentiating myotubes is used. Similarly, in quiescent reserve cells, which express low levels of MyoD, myostatin promoter activity was indeed low compared to that in differentiated myotubes, which contain high levels of active MyoD. In proliferating synchronized C2C12 myoblasts, the peak expression of MyoD is detected in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Much like for MyoD, myostatin promoter activity and protein levels were at their peak in G1 phase, indicating that during cell cycle progression myostatin expression in G1 was regulated by MyoD. However, unlike MyoD levels, myostatin levels were not minimal at G1/S or G0 phase. During G0 and G1/S phases the myostatin promoter activity could be independent of MyoD expression.

In summary, we show that the myostatin promoter sequence contains several muscle-specific and other cis elements, some of which are well conserved during evolution. Among the MRFs, MyoD preferentially up-regulates myostatin gene expression in C2C12 cells, and we propose a genetic hierarchy in which MyoD controls myogenesis by regulating myostatin gene expression during the embryonic, fetal, and postnatal stages.

Acknowledgments

M.P.S. and R.K. contributed equally to this paper.

We are grateful to Stephen F. Konieczny and Kyung-Sup Kim for MyoD and E47 plasmids. We thank Alex Hennebry for Western blot results. We thank Brett Langley for help in selecting stable cell lines and Mark Jackman for help with graphics. We thank Gerome Demner for help with the luciferase assay and Astrid Authier for technical help. Thanks are also due to Allan Crawford and Monica S. Salerno for critically reading the manuscript.

We are indebted to the Foundation of Research and Technology (New Zealand) for financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amacher, S. L., J. N. Buskin, and S. D. Hauschka. 1993. Multiple regulatory elements contribute differentially to muscle creatine kinase enhancer activity in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:2753-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apone, S., and S. D. Hauschka. 1995. Muscle gene E-box control elements. Evidence for quantitatively different transcriptional activities and the binding of distinct regulatory factors. J. Biol. Chem. 270:21420-21427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass, J., J. Oldham, M. Sharma, and R. Kambadur. 1999. Growth factors controlling muscle development. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 17:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bober, E., G. Lyons, T. Braun, G. Cossu, M. Buckingham, and H. H. Arnold. 1991. The muscle regulatory gene, myf6, has a biphasic pattern of expression during early mouse development. J. Cell Biol. 113:1255-1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catala, F., R. Wanner, P. Barton, A. Cohen, W. Wright, and M. Buckingham. 1995. A skeletal muscle-specific enhancer regulated by factors binding to E and CArG boxes is present in the promoter of the mouse myosin light-chain 1A gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4585-4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceccarelli, E., M. J. McGrew, T. Nguyen, U. Grieshammer, D. Horgan, S. H. Hughes, and N. Rosenthal. 1999. An E box comprises a positional sensor for regional differences in skeletal muscle gene expression and methylation. Dev. Biol. 213:217-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faerman, A., D. J. Goldhamer, R. Puzis, C. P. Emerson, and M. Shani. 1995. The distal human MyoD enhancer sequences direct unique muscle-specific patterns of lacZ expression during mouse development. Dev. Biol. 171:27-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez-Cadavid, N. F., W. E. Taylor, K. Yarasheski, I. Sinha-Hikim, K. Ma, S. Ezzat, R. Shen, R. Lalani, S. Asa, M. Mamita, G. Nair, S. Arver, and S. Bhasin. 1998. Organization of the human myostatin gene and expression in healthy men and HIV-infected men with muscle wasting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14938-14943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobet, L., L. J. Martin, D. Poncelet, D. Pirottin, B. Brouwers, J. Riquet, A. Schoeberlein, S. Dunner, F. Menissier, J. Massabanda, R. Fries, R. Hanset, and M. Georges. 1997. A deletion in the bovine myostatin gene causes the double-muscled phenotype in cattle. Nat. Genet. 17:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinterberger, T. J., D. A. Sassoon, S. J. Rhodes, and S. F. Konieczny. 1991. Expression of the muscle regulatory factor MRF4 during somite and skeletal myofiber development. Dev. Biol. 147:144-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes, S. M., K. Koishi, M. Rudnicki, and A. M. Maggs. 1997. MyoD protein is differentially accumulated in fast and slow skeletal muscle fibres and required for normal fibre type balance in rodents. Mech. Dev. 61:151-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes, S. M., J. M. Taylor, S. J. Tapscott, C. M. Gurley, W. J. Carter, and C. A. Peterson. 1993. Selective accumulation of MyoD and myogenin mRNAs in fast and slow adult skeletal muscle is controlled by innervation and hormones. Development 118:1137-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeanplong, F., M. Sharma, W. G. Somers, J. J. Bass, and R. Kambadur. 2001. Genomic organization and neonatal expression of the bovine myostatin gene. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 220:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji, S., R. L. Losinski, S. G. Cornelius, G. R. Frank, G. M. Willis, D. E. Gerrard, F. F. Depreux, and M. E. Spurlock. 1998. Myostatin expression in porcine tissues: tissue specificity and developmental and postnatal regulation. Am. J. Physiol. 275:R1265-R1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kambadur, R., M. Sharma, T. P. Smith, and J. J. Bass. 1997. Mutations in myostatin (GDF8) in double-muscled Belgian Blue and Piedmontese cattle. Genome Res. 7:910-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitzmann, M., G. Carnac, M. Vandromme, M. Primig, N. J. Lamb, and A. Fernandez. 1998. The muscle regulatory factors MyoD and myf-5 undergo distinct cell cycle-specific expression in muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 142:1447-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lassar, A. B., R. L. Davis, W. E. Wright, T. Kadesch, C. Murre, A. Voronova, D. Baltimore, and H. Weintraub. 1991. Functional activity of myogenic HLH proteins requires hetero-oligomerization with E12/E47-like proteins in vivo. Cell 66:305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, J. J., Y. A. Moon, J. H. Ha, D. J. Yoon, Y. H. Ahn, and K. S. Kim. 2001. Cloning of human acetyl-CoA carboxylase beta promoter and its regulation by muscle regulatory factors. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2576-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo, R. X., A. A. Postigo, and D. C. Dean. 1998. Rb interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Cell 92:463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall, P., N. Chartrand, and R. G. Worton. 2001. The mouse dystrophin enhancer is regulated by MyoD, E-box-binding factors, and by the serum response factor. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20719-20726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McPherron, A. C., A. M. Lawler, and S. J. Lee. 1997. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 387:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McPherron, A. C., and S. J. Lee. 1997. Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12457-12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murre, C., P. S. McCaw, H. Vaessin, M. Caudy, L. Y. Jan, Y. N. Jan, C. V. Cabrera, J. N. Buskin, S. D. Hauschka, A. B. Lassar, et al. 1989. Interactions between heterologous helix-loop-helix proteins generate complexes that bind specifically to a common DNA sequence. Cell 58:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ott, M., E. Bober, G. Lyons, H. H. Arnold, and M. Buckingham. 1991. Early expression of the myogenic regulatory gene, myf5, in precursor cells of skeletal muscle in the mouse embryo. Development 111:1097-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pang, K. M., and D. A. Knecht. 1997. Partial inverse PCR: a technique for cloning flanking sequences. BioTechniques 22:1046-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quandt, K., K. Frech, H. Karas, E. Wingender, and T. Werner. 1995. MatInd and MatInspector: new fast and versatile tools for detection of consensus matches in nucleotide sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:4878-4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao, M. V., M. J. Donoghue, J. P. Merlie, and J. R. Sanes. 1996. Distinct regulatory elements control muscle-specific, fiber-type-selective, and axially graded expression of a myosin light-chain gene in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3909-3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts, S. B., and F. W. Goetz. 2001. Differential skeletal muscle expression of myostatin across teleost species, and the isolation of multiple myostatin isoforms. FEBS Lett. 491:212-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenthal, N., J. M. Kornhauser, M. Donoghue, K. M. Rosen, and J. P. Merlie. 1989. Myosin light chain enhancer activates muscle-specific, developmentally regulated gene expression in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:7780-7784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudnicki, M. A., T. Braun, S. Hinuma, and R. Jaenisch. 1992. Inactivation of MyoD in mice leads to up-regulation of the myogenic HLH gene Myf-5 and results in apparently normal muscle development. Cell 71:383-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudnicki, M. A., P. N. Schnegelsberg, R. H. Stead, T. Braun, H. H. Arnold, and R. Jaenisch. 1993. MyoD or Myf-5 is required for the formation of skeletal muscle. Cell 75:1351-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Sharma, M., R. Kambadur, K. G. Matthews, W. G. Somers, G. P. Devlin, J. V. Conaglen, P. J. Fowke, and J. J. Bass. 1999. Myostatin, a transforming growth factor-beta superfamily member, is expressed in heart muscle and is upregulated in cardiomyocytes after infarct. J. Cell. Physiol. 180:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tajbakhsh, S., E. Bober, C. Babinet, S. Pourin, H. H. Arnold, and M. Buckingham. 1996. Gene targeting the myf5 locus with nlacZ reveals expression of this myogenic factor in mature skeletal muscle fibres as well as early embryonic muscle. Dev. Dyn. 206:291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas, M., B. Langley, C. Berry, M. Sharma, S. Kirk, J. Bass, and R. Kambadur. 2000. Myostatin, a negative regulator of muscle growth, functions by inhibiting myoblast proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:40235-40243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wehling, M., B. Cai, and J. G. Tidball. 2000. Modulation of myostatin expression during modified muscle use. FASEB J. 14:103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yaffe, D., and O. Saxel. 1977. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature 270:725-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida, N., S. Yoshida, K. Koishi, K. Masuda, and Y. Nabeshima. 1998. Cell heterogeneity upon myogenic differentiation: down-regulation of MyoD and Myf-5 generates ′reserve cells.' J. Cell Sci. 111:769-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]