Abstract

Precise segregation of chromosomes requires the activity of a specialized chromatin region, the centromere, that assembles the kinetochore complex to mediate the association with spindle microtubules. We show here that Mal2p, previously identified as a protein required for genome stability, is an essential component of the fission yeast centromere. Loss of functional Mal2p leads to extreme missegregation of chromosomes due to nondisjunction of sister chromatids and results in inviable cells. Mal2p associates specifically with the central region of the complex fission yeast centromere, where it is required for the specialized chromatin architecture as well as for transcriptional silencing of this region. Genetic evidence indicates that mal2+ interacts with mis12+, encoding another component of the inner centromere core complex. In addition, Mal2p is required for correct metaphase spindle length. Our data imply that the Mal2p protein is required to build up a functional fission yeast centromere.

The molecular mechanisms that are required for the faithful segregation of the duplicated sister chromatids in mitosis are necessary for the accurate inheritance of genetic information. Accurate segregation of chromosomes is dependent on the centromere and an associated kinetochore complex. This complex provides the site on the chromosome for the attachment of the mitotic spindle fibres and is also required for a sensing mechanism that signals correct completion of metaphase and thus allows entry into anaphase. In general the centromere-kinetochore complex is formed at a single position on the chromosome. The cis-acting DNA present at this site varies in sequence composition and complexity in different eucaryotic organisms. In higher eucaryotes, centromeric DNA consists of highly repetitive regions encompassing up to millions of base pairs (reviewed in reference 13) but the exact sequence requirements for centromere function are not well defined. In contrast, the centromere DNA of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is confined to a very well defined 125-bp region containing highly conserved DNA sequence motifs, which is sufficient to mediate accurate segregation of chromosomes in mitosis and meiosis. In addition, substantial progress has been made in the characterization of budding yeast centromere proteins (reviewed in reference 39). The centromere DNA of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe lies in between these two extremes. It is 40 to 120 kb in size and moderately repetitive. The centromere DNA on the three S. pombe chromosomes all consist of a central core region flanked by inverted repeats that can be subdivided into inner and outer repetitive sequences of variable size structure (reviewed in reference 56; see Fig. 4 for cen1). The central core regions have an unusual chromatin architecture that does not show the long-range regular nucleosome ladders (52, 58). This specialized chromatin structure appears to be related to centromere function since mutations that abolish this chromatin structure give rise to high frequencies of chromosome missegregation (27, 54, 57).

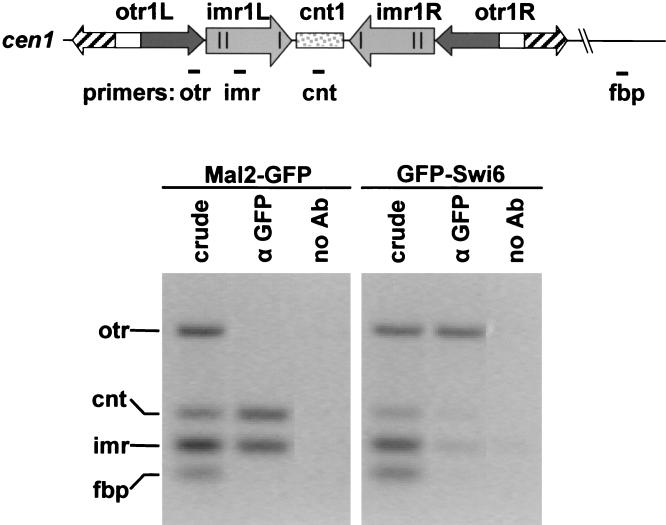

FIG. 4.

Mal2p is associated with the central domain of cen1. Cells expressing Mal2-GFPp or GFP-Swi6p were formaldehyde fixed and processed for ChIP using anti-GFP antibodies. Chromatin in immunoprecipitates and crude extracts was analyzed by multiplex PCR, using primers to amplify regions in cen1: cnt, imr, otr, and an euchromatic negative control locus, fbp. cnt and imr sequences are specifically enriched in Mal2-GFPp ChIPs, indicating association of Mal2p fusion protein with the central domain of cen1. In contrast, otr sequences, but not central domain sequences, are specifically enriched in GFP-Swi6p ChIP, as shown previously (49).

Marker genes that are inserted within the fission yeast centromere DNA are transcriptionally repressed (1, 2). This silenced chromatin is underacetylated and consists of distinct protein interaction domains (16, 49). The Swi6p protein, which is a heterochromatin protein 1 counterpart, and Chp1p associate with the outer repetitive centromere DNA elements and require the rik1+ and clr4+ gene products for this localization (reviewed in reference 50). Clr4p, a homolog of the mammalian SUV39H1 histone methylase, modifies a specific lysine of histone H3 (53), and this methylase activity is required for the localization of Swi6p at the centromere (5). Mutations in any of these four genes lead to alleviation of silencing in the outer repetitive domains and to impaired centromere function (2, 15). Recently, association of Rad21p, a subunit of the sister chromatid cohesion complex, with the outer repeat regions has also been demonstrated (61). This association required a functional swi6+ gene product, indicating that heterochromatin is needed for cohesion between sister centromeres (8).

In contrast, the S. pombe Mis6p and Mis12p proteins associate only with the central centromeric region and are required to maintain the special chromatin structure of the core region (27, 54). These proteins are needed for correct metaphase spindle length, and mutations in either of these two essential genes lead to extreme missegregation of chromosomes. Furthermore, Mis6p is required for transcriptional silencing of genes placed within the central core region but not for silencing of the outer centromeric repeats (49). Cnp1p, the S. pombe homolog of the mammalian CENP-A protein, which is a centromere-specific histone H3 variant, is also associated with the central centromere region. This association is Mis6p dependent (57). Recently, Cbh2p, an S. pombe CENP-B homolog, was also shown to localize to the central core region (34).

In this study we have identified a new essential component of the fission yeast centromere. Through a screen designed to isolate novel fission yeast genes required for chromosome segregation, we previously reported the identification of the mal2+ gene, which codes for a nuclear 34-kDa protein (19). The conditionally lethal temperature-sensitive mal2-1 allele gave rise to increased loss of a minichromosome at the permissive temperature and led to severe missegregation of endogenous chromosomes at the restrictive temperature. In the present study, the function of Mal2p in mitosis was analyzed further. Our data show that Mal2p is a bona fide centromere protein that associates specifically with the central centromeric region, where it is required for the establishment of a functional centromere.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Genotypes of strains are listed in Table 1. All new strains were obtained by crossing the appropriate strains followed by tetrad analysis and determination of the genotype. For determination of genetic interaction, at least three double mutants were tested per cross. The tetrad analysis of the mal2-1 strain crossed to the dis1-288 strain gave no viable double mutants. Therefore, the genotypes of the three growing spores from such a tetrad were determined and the genotype of the nongrowing spore was inferred. We tested a total of 36 tetrads; 25 of these contained nongrowing dis1-288 mal2-1 double-mutant spores. S. pombe strains were grown in rich medium (YE5S) or Edinburgh minimal medium (EMM) with appropriate supplements (43). In silencing assays, N/S refers to EMM with glutamate containing adenine, leucine, and uracil at 75 mg/liter each. 5-Fluroorotic acid (5-FOA) plates contain N/S supplemented with 2 g of 5-FOA (Toronto Research Chemicals) per liter. Ura− is N/S medium without uracil. YE5S containing 100 mg of G418 (Calbiochem) per liter was used for selecting Kanr cells. EMM with 5 μg of thiamine per ml was used to repress the expression from the nmt1+ promoter. Nitrogen source-deficient EMM-N lacking glutamate was used for nitrogen starvation experiments.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Name | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| UFYS220 | h−mal2-1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D18 | U. Fleig |

| UFYS135 | h+mal3Δ::his3+leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D18 his3Δ | U. Fleig |

| FY336 | h+leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E cnt1/TM1 (NcoI )::ura4+ | R. Allshire |

| FY340 | h+leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E TM1 (NcoI )-ura4+ Random int. | R. Allshire |

| FY489 | h−leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E | R. Allshire |

| FY498 | h+leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E imr1 R (NcoI )::ura4+oriI | R. Allshire |

| FY648 | h+leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E otr1R(Sph1 )::ura4+ | R. Allshire |

| FY986 | h+leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E otr1 L (dg1a/HindIII )::ura4+oriII | R. Allshire |

| FY2214 | h−leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D18 ars1 (MluI)::pREP81Xgfpswi6-LEU2+ | R. Allshire |

| IH1356 | h−cut12.M33-GFP/ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 | I. Hagan |

| SS560 | h−mph1Δ::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 | S. Sazer |

| SS638 | h−mad2Δ::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | S. Sazer |

| h−rad21-K1-ura4+ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his7-366 | K. Tatebayashi | |

| NK04 | h−leu1-32 ura4−alp14Δ::Kanr | T. Toda |

| h−nda3-KM311 ade6-210 leu1-32 ura− | M. Yanagida | |

| h−mis4-242 leu1-32 | M. Yanagida | |

| h−mis6-302 leu1-32 | M. Yanagida | |

| h−mis12-537 leu1-32 | M. Yanagida | |

| h−mis12-GFP/LEU2+leu1-32 | M. Yanagida | |

| h−cut4-553 leu1-32 | M. Yanagida | |

| h−cut9-665 leu1-32 | M. Yanagida | |

| h−dis1-288 leu1-32 | M. Yanagida | |

| UFY177 | h+mal2-GFP/Kanrleu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D18 | This study |

| UFY256 | h+mal3Δ::his3+mal2-1 leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY337 | h−alp14Δ::Kanrmal2-1 leu1-32 ura4−ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY352 | h−mal2-1 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E TM1 (NcoI )-ura4+ Random int. | This study |

| UFY353 | h−mal2-1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E otr1L(dg1a/HindIII )::ura4+oriII | This study |

| UFY355 | h−mal2-1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E cnt1/TM1(NcoI )::ura4+ | This study |

| UFY357 | h−mal2-1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E imr1R(NcoI )::ura4+oriI | This study |

| UFY359 | h−mal2-1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-DS/E otr1R(Sph1 )::ura4+ | This study |

| UFY361 | h−mad2Δ::ura4+mal2-1 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY363 | h+mph1Δ::ura4+mal2-1 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 | This study |

| UFY370 | h+mis6-302 mal2-1 | This study |

| UFY372 | h+mis12-537 mal2-1 | This study |

| UFY374 | h−cut9-665 mal2-1 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY376 | h+mis4-242 mal2-1 | This study |

| UFY378 | h−mal2-GFP/Kanrnda3-KM311 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura− | This study |

| UFY384 | h+mal2-GFP/Kanrmis12-537 ade6-M210 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY394 | h+cut12.M33-GFP/ura4+mal2-1 ura4-D18 | This study |

| UFY398 | h−rad21-K1-ura4+mal2-1 | This study |

| UFY404 | h−cut4-553 mal2-1 | This study |

| UFY417 | h−mal2-1 mis12-GFP/LEU2+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | This study |

Culture synchronization and FACS analysis.

Nitrogen starvation experiments were carried out as described previously (54). Briefly, cells growing in EMM were washed, resuspended in EMM-N (2 × 107 cells/ml), and incubated at 24°C for 12 to 16 h before being transferred to YE5S (4 × 106 cells/ml) at 35°C. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was performed as described previously (38) using a Becton-Dickinson FACSort apparatus. All experiments were repeated at least twice.

DNA methods.

We generated in strain UFY177 a genomic mal2+ open reading frame (ORF) without the stop codon fused to GFP ORF via PCR-based gene targeting (4) by using the oligonucleotide: 5′-AAGGATGAAACCAAGGCGGAAATTAAGGAATATGGACGATTATTTGGTGCAATCGTAAATAACTAACAAGTATAAAGTTTGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC-3′ and 5′-AACTATCTTTATTAGACAACAAACGTTGGGTTAATATACTTGTATCACACCTAACTGCTCCAGAAAGTCATGCTTCGTTACGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA-3′. The resultant Kanr transformants were tested via PCR analysis for correct fusion of the mal2+ and GFP ORFs. Correct transformants were tested for alterations in growth at various temperatures, sensitivity to thiabendazole, and genome stability in comparison to the isogenic wild-type strain (data not shown). Cells transformed with the mph1+ overexpression construct pREP3X-mph1 or an empty vector were streaked on EMM-thiamine. To induce mph1+ overexpression, cells were grown in thiamine-free EMM liquid medium for 18 to 24 h at 24°C. The sequence of mal2-1 was determined by amplification of the ORF by PCR using Pfu DNA polymerase (Gibco/BRL) and the primers 5′-ATGGACGATGAAGAAGGC-3′ and 5′-TAACGAAGCAT GACTTTC-3′. The PCR-generated fragment was subcloned into SmaI-cut pBluescript (Strategene) and sequenced. Two independent PCR analyses were carried out.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed as described previously (17, 49). Strains containing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged proteins were used for ChIP: Mal2-GFPp (UFY177) and GFP-Swi6p (FY2214; 51). A 1-μl volume of rabbit anti-GFP antibody (Molecular Probes) was used in the ChIP together with 25μl of protein A-agarose (Roche). Multiplex PCR was used for analysis of centromeric chromatin in crude extracts and immunoprecipitates, using the following primer pairs: cnt (central core), 5′-AACAATAAACACGAATGCCTC-3′ and 5′-ATAGTACCATGCGATTG TCTG-3′; imr (innermost repeat), 5′-GGCTACCAGCATTGTTATTCATAACC-3′ and 5′-GGACTTTCTGGCGACTAATACTTGG-3′; otr (outer repeat), 5′-CACATCATCGTCGTACTACAT-3′ and 5′-GATATCATCTATATTTAATGACTACT-3′; and fbp1+ (euchromatic control), 5′-AATGACAATTCCCCACTAGCC-3′ and 5′-ACTTCAGCTAGGATTCACCTGG-3′. PCR mixtures contained 2 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2μl of ChIP sample or 2μl of a 1/10 dilution of crude sample, and 50 ng of each primer in a 25-μl reaction mixture.

RNA analysis.

Cells were grown in YE5S at 25°C to 5 × 106 cells/ml or shifted to 35°C for 5 h before RNA extraction. cDNA was prepared by oligo (dT)15-primed RT-PCR, and competitive PCR of ura4+ and ura4-DS/E was performed as described previously (16). The primers used for amplification of ura4+ and ura4-DS/E were 5′-CCATACAGTGCCAGGCGAG-3′ and 5′-GGTAATGTTGTAGGAGCATG-3′; the expected DNA fragments were 656 and 376 bp for ura4+ and ura4-DS/E, respectively. Electrophoretic separation of the RT-PCR products was followed by Southern analysis using a 1.7-kb HindIII ura4-DS/E DNA fragment as probe. ura4+ levels were normalized to ura4-DS/E and quantified relative to wild-type strains as described previously (49) using Image Quantification software (Molecular Dynamics).

Micrococcal nuclease digestion.

Nuclei and chromatin were isolated as described previously (58). Chromatin was digested for 1, 2, 4, 8, or 10 min using 600 U of micrococcal nuclease (Fermentas) per ml. Southern analysis was carried out using cnt2, imr2, and otr2 probes isolated from plasmids pKNS-cc2 and pKH-K (6).

Yeast two-hybrid interaction assay.

Bait mal2+ and prey mis12+ were obtained by PCR amplification using Pfu DNA polymerase (Gibco/BRL) from genomic DNA, cloned into pAS2ΔΔ and pACTIIst, respectively (21), and verified by sequencing. Plasmids were cotransformed into strain PJ69-4A (35), and expression of the bait and prey fusion proteins was confirmed by Western analysis with monoclonal antibodies against the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (Santa Cruz) and HA (Roche), respectively (data not shown). For the lacZ test, 104 cells pregrown in medium selecting for both plasmids were spotted onto selective plates and incubated at 30°C for 1 day. Then 10 ml of X-Gal mixture (0.5 M potassium phosphate buffer [pH 7.5], 0.5% agarose, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.01% 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [X-Gal]) was poured on the plates, and the plates were further incubated at 30°C.

Microscopy.

Immunofluorescence microscopy was done as described previously (30). For tubulin staining, primary monoclonal anti-tubulin antibody TAT1 (66) followed by Cy3-conjugated secondary sheep anti-mouse antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Strains expressing GFP fusions were observed in cells fixed with ethanol and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or in formaldehyde-fixed cells followed by indirect immunofluorescence with mouse anti-GFP (Clontech) and fluorescein isothiocyanata-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed as described previously (17) using YIp10.4, the k repeat, and cosmid c8d2 as probes for rDNA, centromere DNA, and chromosome II right arm, respectively. Probes were labeled by nick translation (Gibco/BRL kit) by incorporating Cy3-dUTP (Amersham). After hybridization and washes, mounting medium (Vector Laboratories Inc.) supplemented with 0.5 μg of DAPI per ml was applied to each slide under a coverslip. Photomicrographs were obtained using a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope coupled to a charge-coupled device camera (SensiCam; PCO Computer Optics GmbH), and image processing and analysis were carried out using Image-Pro Plus software. For quantitative analyses of mal2-1 phenotypes by FISH and immunostaining, a minimum of 200 cells were scored per experiment, except for the analysis of metaphase spindle length, where 100 metaphase cells/strain expressing Cut12-GFPp were counted. At least two independent cell populations were assayed for each experiment.

RESULTS

Unequal segregation of chromatin in mal2-1 cells is not caused by premature sister chromatid separation.

The most remarkable phenotype of temperature-sensitive mal2-1 mutant cells was the severely decreased chromosome transmission fidelity. At the permissive temperature, this phenotype was manifested by a dramatic increase in the loss of a nonessential chromosome. At the restrictive temperature, abnormal segregation of chromatin at anaphase resulting in asymmetrical segregation of the chromatin into two daughter nuclei was observed (19). To investigate the nature of the mutation in the mal2+ ORF leading to these phenotypes, we determined the sequence of the mal2 gene in the mal2-1 strain (see Materials and Methods) and found a single-base-pair change from G to A at position 829 of the ORF. This alteration results in a change from glutamic acid to lysine at position 277 of Mal2p.

To test if the phenotype of unequal distribution of chromosomes in the mal2-1 mutant was caused by premature sister chromatid separation, we examined the cohesion of sister chromatids in mal2-1 cells by FISH. Cohesion is established during S phase and persists until the early stages of mitosis. Since cohesion is not confined to centromeres but extends along the chromosome arms, we used two different FISH probes to monitor sister chromatid cohesion in mal2-1 cells. One probe was homologous to DNA on the right arm of chromosome II, and the other was homologous to DNA on the centromere of chromosome III. mal2-1 and wild-type cells were synchronized in the G1 phase of the cell cycle by nitrogen starvation at 24°C and then released into rich medium at 35°C. Cell cycle progression was monitored by measuring the DNA content. Entry into S phase (approximately 3.5 hrs) occurred with similar kinetics in wild-type and mal2-1 cells, and staining of the chromatin with DAPI as well as anti-tubulin immunofluorescence showed that entry into mitosis occurred around 4.5 to 5 h after the release (Fig. 1A and data not shown). Entry into anaphase was sightly delayed in the mal2-1 population compared to the wild-type strain. This appeared to be due to the transient activation of the spindle checkpoint in mal2-1 cells described below.

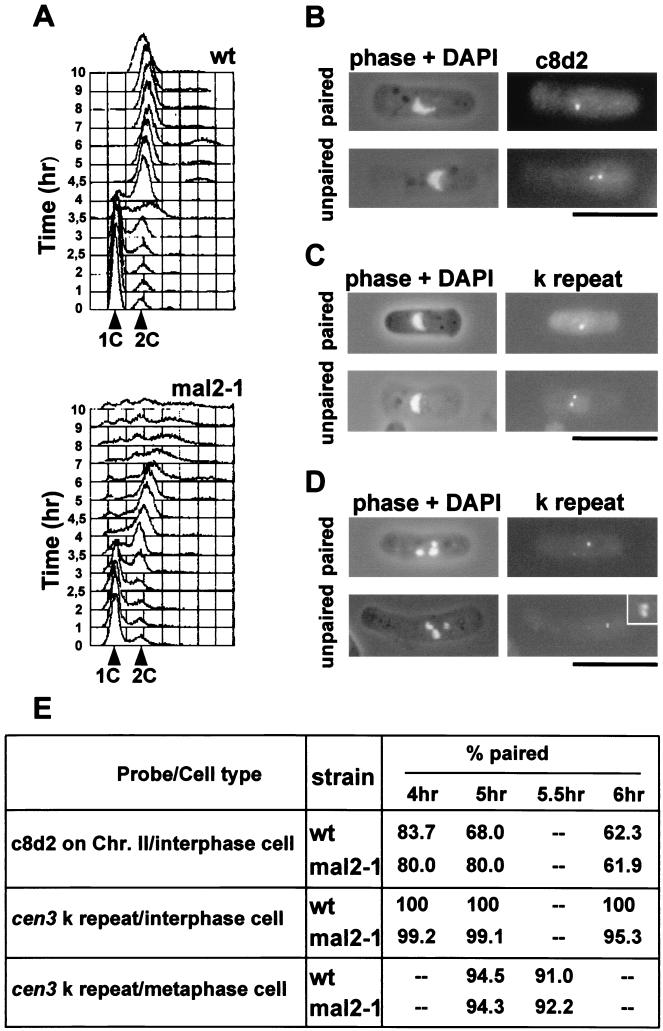

FIG. 1.

Sister chromatid cohesion in mal2-1 cells. (A) G1-arrested wild type (wt) and mal2-1 cells were released into the cell cycle at 35°C for 0 to 10 h, and the DNA content was determined by flow cytometric analysis. (B to D) Cohesion of sister chromatids in mal2-1 strain was assayed by FISH analysis using a unique sequence on the right arm of chromosome II (c8d2) (B) and the centromeric k repeat as probes (C and D). Examples of interphase (B and C) and metaphase (D) cells with paired or separated FISH signals are shown. For k-repeat FISH, the brightest signal was consistently observed on the smallest chromosome (chromsome III) in metaphase cells (upper panel in panel D). An enlargement of the FISH signal on chromosome III is shown in an inset of the lower panel. Bars, 10 μm. (E) The percentage of paired sister chromatids in synchronized mal2-1 and wild-type cells at 4 to 6 h after incubation at 35°C was analyzed using FISH. At least 100 interphase or metaphase cells were counted per time point and strain.

Sister chromatid cohesion in interphase cells, which were identified by their characteristic crescent-shaped nuclei, was analyzed by FISH using a unique sequence from the right arm of chromosome II as the probe. We counted the number of paired and unpaired chromosome II sister chromatids in wild-type and mal2-1 cells (Fig. 1B) and found that the frequency of interphase cells with two separated FISH signals was similar in the two cell populations at all time points analyzed (Fig. 1E).

We investigated the cohesion of sister centromeres in postreplicative interphase cells by studying cen3 DNA by using FISH. The fission yeast centromeres cen1, cen2, and cen3 contain different numbers of a repeated element designated dg or k (10, 18). Using the k repeat DNA sequence as a FISH probe consistently revealed bright signals for cen3 but gave no or very faint signals for the other two centromeres since they have a much smaller number of the k-repeat sequences than does cen3 (64). Using the k-repeat FISH probe, we could therefore specifically identify the behavior of cen3 sister centromeres (Fig. 1C). Again, we found no significant difference in the separation of cen3 DNA between interphase wild-type and mal2-1 cells (Fig. 1E), indicating that premature sister chromatid separation in interphase is not the cause of the asymmetric chromatin distribution observed in mal2-1 anaphase cells.

We also determined if premature sister centromere separation occured in mal2-1 metaphase cells. In the synchronized mal2-1 and wild-type cell populations described above, metaphase cells were found predominantly at the 5- to 6.5-h time points. Using the k-repeat FISH probe, the cen3 DNA was visualized as a single bright dot on chromosome III (the smallest of the three highly condensed chromosomes; Fig. 1D, upper panel) or, very rarely, as two dots with similar brightness (Fig. 1D, lower panel).

Quantitation of the number of paired and unpaired cen3 DNAs in metaphase cells revealed no significant differences between wild-type and mal2-1 cells (Fig. 1E).

These data indicate that sister chromatid cohesion is established and maintained in mal2-1 mutant cells and that Mal2p protein does not appear to be required for maintenance of cohesion between sister chromatids in interphase or metaphase. Supporting these data is our finding that mal2-1 did not show genetic interaction with the mutant mis4-242 or rad21-K1 alleles (data not shown). Mis4p is required for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion, while Rad21p is a component of the cohesion complex in fission yeast (23, 61).

Missegregation of chromatin in mal2-1 cells is due to nondisjunction of sister chromatids.

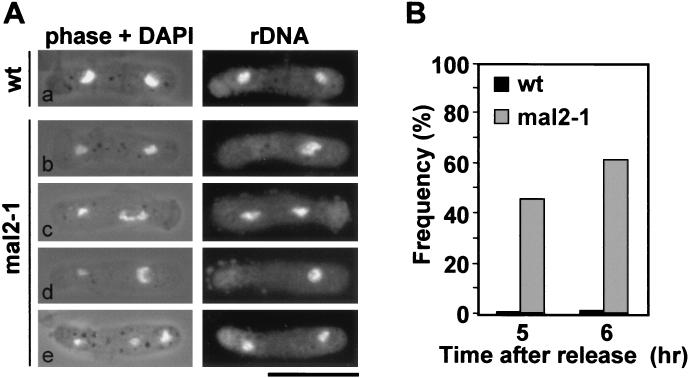

To further characterize the severe missegregation of endogenous chromosomes at the restrictive temperature, we analyzed the segregation behavior of sister chromatids in anaphase by monitoring the segregation of the repeated rDNA sequences located on chromosome III by FISH (60) (Fig. 2). Using synchronized cell cultures (Fig. 1A), we quantified the binucleate cells that showed a symmetrical or asymmetrical distribution of the rDNA. The rDNA distribution was determined in binucleate cells with seemingly equal segregation of DAPI-stained chromatin as well as those which showed unequal segregation of the chromatin. A number of examples are depicted in Fig. 2A. The frequency of binucleate cells with a single rDNA FISH signal, indicating nondisjunction of sister chromatids III, reached 62% in mal2-1 cells compared to 3.7% in wild-type cells (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Missegregation of chromatin in mal2-1 anaphase cells is caused by nondisjunction of sister chromatids. (A) The segregation behavior of chromosome III sister chromatids in wild-type (wt) and mal2-1 binucleate cells was analyzed using rDNA FISH. (a) wild-type cell with equally separated chromatin (stained with DAPI) and rDNA signals (on chromosome III); (b to e) mal2-1 cells with seemingly equally separated chromatin without separation of rDNA (b), unequal separation of chromatin but separation of chromosome III sister chromatids (c), unequal separation of chromatin and rDNA (d), and unequal separation of chromatin with lagging chromosome and equal separation of rDNA (e). Bar, 10μm. (B) Diagrammatic representation of the number of binucleate cells with a single rDNA FISH signal at 5 and 6 h after the release from G1 arrest (see Fig. 1). At least 300 cells were counted per strain and time point.

These data imply that nondisjunction of sister chromatids at anaphase is a major cause of the observed unequal distribution of chromatin in mal2-1 cells.

Mal2p is a component of the centromere.

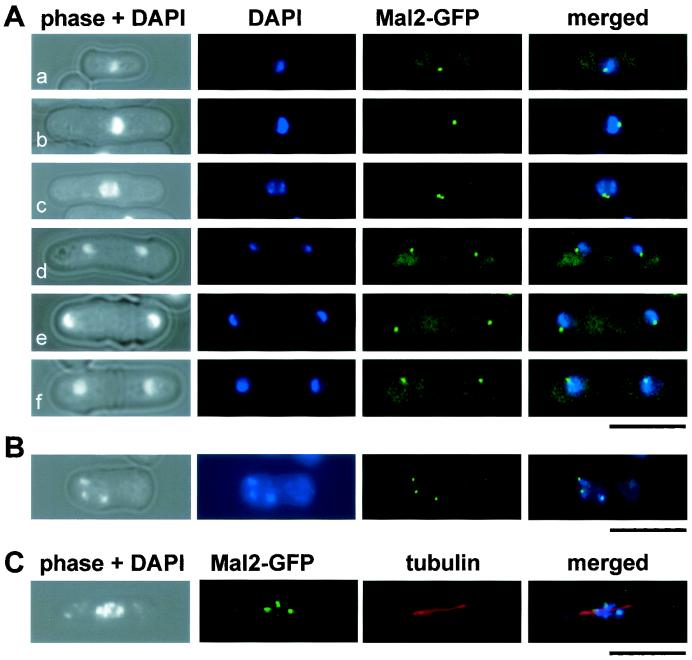

We previously reported that an overproduced Mal2-GFPp fusion protein accumulated in the nucleus (19). A specific subnuclear localization could not be determined at that time due to the low intensity of the fluorescence signal. To determine if Mal2p has a specific subnuclear localization, a fluorescence-improved version of GFP was fused to the COOH-terminal end of the endogenous mal2+ coding region expressed under the control of the native mal2+ promoter. Strains expressing the Mal2-GFPp fusion protein were indistinuishable in phenotype from the isogenic wild-type strain, indicating that the tagged gene was functional (data not shown) (see Materials and Methods).

Microscopic examination of interphase cells expressing the Mal2-GFPp protein revealed a single green fluorescent dot near the nuclear periphery (Fig. 3A, panels a and b), while in anaphase and postanaphase cells, two dots were observed that cosegregated with the separated chromatin (panels c to f). This localization pattern is characteristic of components of the spindle pole body (SPB) and centromere proteins, since centromeres are clustered at the SPB for most of the cell cycle (see, e.g., references 14, 22, 29, and 54). To determine whether Mal2p is associated with the SPB or the centromere, Mal2-GFPp was expressed in nda3-KM311, a cold-sensitive β-tubulin mutant that arrests at metaphase due to defective mitotic spindle formation (33). Since the three hypercondensed fission yeast chromosomes can be observed individually in metaphase-arrested cells, we would see three GFP signals if Mal2-GFPp were localized at centromeres. As shown in Fig. 3B, three fluorescent signals, each of which was associated with a highly condensed chromosome, were seen in arrested nda3-KM311 cells. Furthermore, when Mal2-GFPp localization was determined in metaphase cells arrested by overexpression of Mph1p (a component of the spindle assembly checkpoint in fission yeast [31]), we also obtained a GFP signal on each of the three chromosomes positioned on a short spindle (Fig. 3C). In addition, we found that Mal2-GFPp colocalized with a HA-tagged version of Mis6p, which was identified previously as a component of the centromere (reference 54 and data not shown). Our data thus demonstrate that Mal2p localizes at centromeres throughout the cell cycle.

FIG. 3.

Localization of the Mal2-GFPp fusion protein at centromeres. (A) Localization of Mal2-GFPp protein in wild-type cells at various cell cycle stages. Fixed cells were stained with DAPI. (B) Localization of the Mal2p fusion protein in a metaphase-arrested nda3-KM311 cell. (C) Localization of Mal2-GFPp in a wild-type cell arrested in metaphase due to overexpression of mph1+. GFP signals, spindles, and condensed chromosomes were simultaneously observed by staining with anti-GFP antibody, anti-tubulin antibody, and DAPI. Bars, 10 μm.

Mal2p is associated with the central region of fission yeast centromeres.

Fission yeast centromeric DNA consists of large inverted repeats with a central core (cnt) sequence that is flanked by inner (imr/B) and outer (otr/K + L) repeats (reviewed in reference 11) (Fig. 4). To identify the centromere region with which the Mal2p protein associates, ChlP was carried out (49). Cells expressing the Mal2-GFPp fusion were fixed and processed for ChIP using anti-GFP antibodies. Chromatin immunoprecipitates and crude extracts were analyzed by multiplex PCR, using primers to amplify the cnt, imr, and otr regions in the centromere of chromosome I and a euchromatic locus, fbp1+, as a negative control (Fig. 4). We found that cnt and imr sequences were specifically enriched in Mal2-GFPp ChIPs (Fig. 4), indicating an association of the Mal2p fusion protein with the central domain of centromere 1. In contrast, GFP-Swi6p ChIP analysis showed enrichment of otr sequences but not central domain sequences, as previously reported (49).

The Mal2p protein affects silencing at the central centromeric region.

Marker genes that are placed within the centromere DNA are transcriptionally repressed (1, 2), and mutations in genes encoding centromere components lead to defective centromeric silencing (reviewed in reference 50).

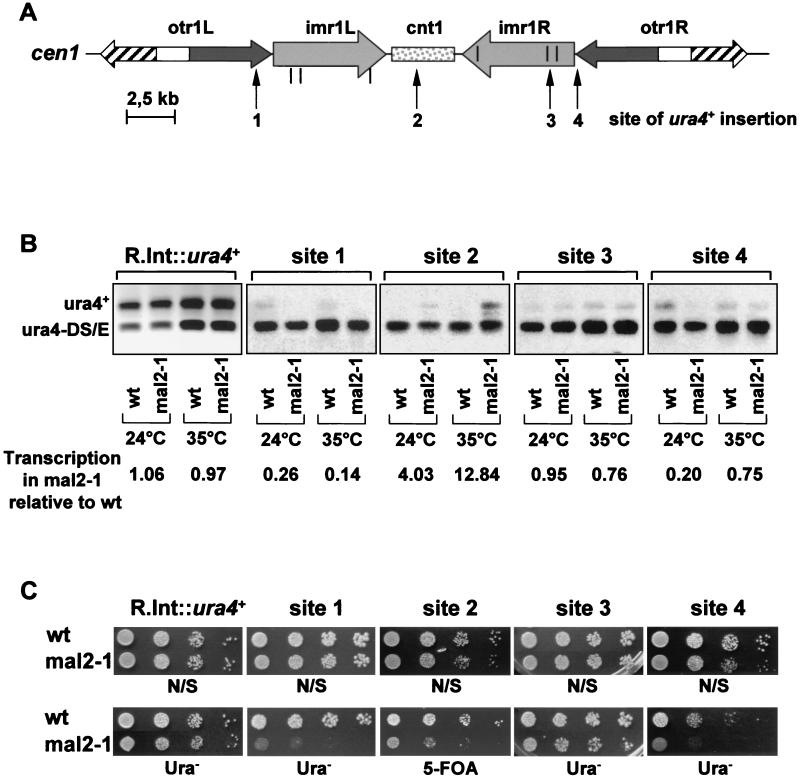

To test whether Mal2p plays a role in centromeric silencing, we assayed the transcription of the ura4+ gene inserted at four different regions of centromere 1 (cen1) in a mal2-1 mutant background by using quantitative RT-PCR (2, 49). To this end, cDNA was generated from mal2-1 and corresponding wild-type strains, grown at 24 or 35°C, that contained the ura4+ gene within cen1 and expressed a ura4-DS/E minigene at the endogenous ura4+ locus (Fig. 5A) (2). As a control, a strain with a fully expressed random integrant of ura4+, R.Int::ura4+, was used. The PCR assay was performed with the same primer pair to amplify the full-length ura4+ (656 bp) as well as the ura4-DS/E minigene (376 bp). The presence of mal2-1 derepressed the transcription of the ura4+ marker within the central core even at the permissive temperature of 24°C (Fig. 5B, site 2). This finding is in agreement with the observation that the mal2-1 strains show increased genome instability even at this temperature (19). At the restrictive temperature (35°C), alleviation of silencing at the central core domain was further increased in a mal2-1 mutant background (site 2). mal2-1 therefore specifically derepresses silencing within the central core region. Alleviation of silencing within other centromeric regions in a mal2-1 background was not observed, (sites 1, 3, and 4); in fact, our data indicate that silencing was somewhat increased within the outer centromere regions (sites 1 and 4).

FIG. 5.

Mal2p is involved in centromeric silencing. (A) Diagrammatic representation of the insertion sites of the ura4+ marker in cen1 (2). (B) Competitive PCR was performed on cDNA generated via reverse transcription-PCR from the wild-type (wt) and corresponding mal2-1 strains described in panel A. The strains have the full-length ura4+ gene inserted at sites 1 to 4 in cen1 and fully expressed ura4-DS/E minigene at the endogenous ura4+ locus (2). The separated PCR products were quantified. Levels of ura4+ were normalized to ura4-DS/E in the mal2-1 mutant strains and expressed relative to values obtained for the corresponding wild-type strains. mal2-1 and wild-type strains were grown at 24°C or pre-grown at 24°C and then shifted to 35°C for 5 h before RNA extraction. (C) Serial-dilution patch test for growth of these strains on uracil-minus or 5-FOA medium. Dilutions shown were 10-fold starting with 104 cells. Strains were pregrown in liquid nonselective (N/S) medium at 24°C, spotted onto N/S (nonselective EMM), Ura− (N/S medium without uracil) or 5-FOA (N/S medium supplemented with 5-FOA) plates and incubated at 24°C for 5 to 6 days. R.int::ura4+; control strains that have a fully expressed ura4+ gene integrated at a random position.

The silencing data obtained by reverse transcription-PCR were confirmed by plating cells with 5-FOA (to allow the growth of only Ura− cells) or without uracil (to allow the growth of only Ura+ cells). As shown in Fig. 5C, mal2-1 cells with an insertion of ura+ within the central core of cen1 (site 2) are unable to grow properly on 5-FOA-containing medium while the corresponding wild-type strain is able to grow. These data again indicate that silencing of ura4+ within the central core region is alleviated in a mal2-1 mutant background. In contrast, mal2-1 strains that have the ura4+ inserted within the outer centromeric regions (sites 1 and 4) are unable to grow on uracil-free medium, indicating increased silencing within these regions.

Centromere chromatin structure is altered in a mal2-1 mutant background.

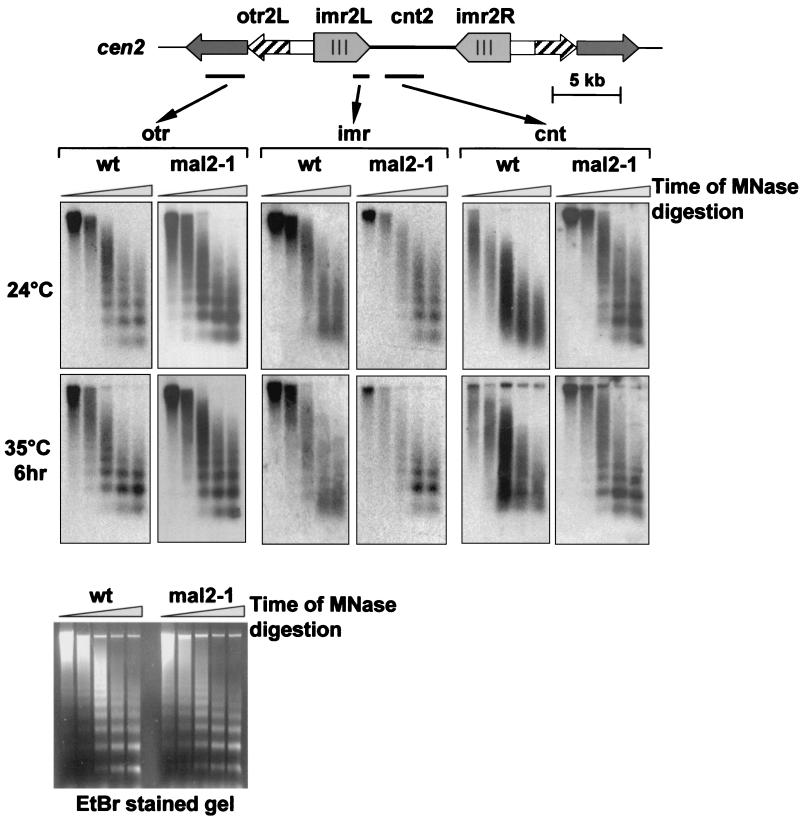

Analysis of wild-type centromeric chromatin using micrococcal nuclease has shown that the inner centromere region has a specialized chromatin structure that does not show the long-range regular nucleosome ladders (52, 58). Recent studies have demonstrated that proteins associated with the inner centromere are required for maintaining this smeared nucleosome pattern (27, 54, 57). To determine if Mal2p also plays a role in centromere architecture, we analyzed centromeric chromatin in a mal2-1 mutant background by using partial digestion with miccrococcal nuclease. As has been shown previously, chromatin isolated from wild-type cells showed regular nucleosome ladders when the outer centromeric repeat (dg repeat in otr2) was used as a hybridization probe while smeared patterns were obtained when cnt2 and imr2 probes were used (Fig. 6). These results were independent of the growth temperature used (Fig. 6). In chromatin isolated from mal2-1 mutant cells, no deviation from the wild-type pattern was observed when otr2 chromatin was analyzed (Fig. 6). However, the smeared chromatin pattern observed for wild-type cnt2 and imr2 regions was abolished in mal2-1 cells; instead, regular nucleosome ladders were observed even at the permissive temperature (24°C) (Fig. 6). These data indicate that the Mal2p protein plays a role in maintaining the inner centromere structure.

FIG. 6.

Mal2p affects the centromere-specific chromatin pattern. Chromatin was isolated from wild-type (wt) and mal2-1 cells grown at the permissive temperature (24°C) or pregrown at 24°C and then shifted to the nonpermissive temperature for 6 h (35°C). Chromatin was digested with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) for 1, 2, 4, 8 and 10 min, separated by gel electrophoresis, and analyzed by Southern analysis using three probes from centromere 2: cnt2, imr2, and otr2. The ethidium bromide (EtBr)-stained agarose gels used for Southern analysis with the imr probe are shown at the bottom.

Interaction between Mal2p and other centromere proteins.

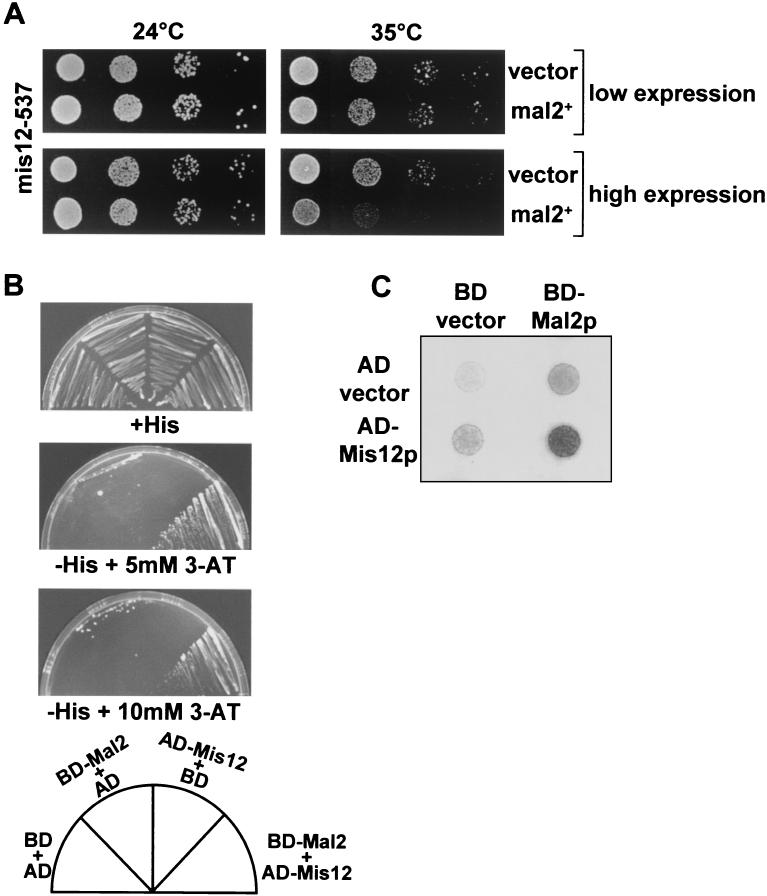

Mal2p associates specifically with the innermost centromere cnt region. We therefore tested for possible genetic interactions between mal2+ and genes encoding the Mis6p and Mis12p proteins that also associate with the cnt region by using the “synthetic dosage lethality” assay (27, 41, 54). In this assay, specific genetic interactions can be identified by the presence of a nongrowth phenotype that is caused by overproducing a wild-type reference gene in strains that carry potential target mutations. Overexpression of the wild-type mal2+ gene under the control of the regulatable nmt1+ promoter did not produce a noticeable phenotype in wild-type or mis6-302 strains grown at various temperatures (data not shown). However, when mal2+ was overexpressed in the mis12-537 mutant strain, we observed a severe reduction in growth (Fig. 7A). This reduced growth phenotype was observed only when mal2+ was overexpressed at incubation temperatures of 34 and 35°C (Fig. 7A and data not shown). At 35°C, growth of the mis12-537 strain was affected slightly (Fig. 7A, compare the vector control at 24 and 35°C). No reduced growth was observed in the mis12-537 strain when expression of mal2+ was reduced by down-regulation of the nmt1+ promoter or at temperatures of ≤32°C (Fig. 7A and data not shown). These data imply that mal2+ and mis12+ show genetic interaction and raised the question whether Mal2p and Mis12p show a physical association. Since we were unable to do coimmunoprecipitation experiments due to technical reasons, we investigated whether these two proteins interact in a yeast two-hybrid system. Two fusion proteins, one a fusion of Mal2p with the DNA-binding domain of Gal4 (BD) and the other a fusion of Mis12p with the transcriptional activation domain of Gal4 (AD), were coexpressed in budding yeast host strain PJ69-4A (35). Interaction of the coexpressed fusion proteins results in the activation of HIS3 and lacZ transcription from reporter constructs present in PJ69-4A, and this can be monitored by the ability of the transformed strains to grow on 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) plates or by the blue color of colonies on X-Gal plates as a result of the increase in β-galactosidase activity (21). All strains grew well on histidine-containing media (Fig. 7B) but on His− plates with different amounts of 3-AT only the strain that expressed both Mal2p and Mis12p fusion proteins grew well; the negative control strains expressing only one or neither of the fusion proteins did not grow (Fig. 7B). Identical results were obtained with the β-galactosidase assay; only the strain that expressed the Mal2p and the Mis12p fusion proteins gave rise to a dark blue color on indicator plates (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that Mal2p and Mis12p might interact in vivo.

FIG. 7.

Interaction between mal2+ and mis12+. (A) Colony formation of a mis12-537 strain is reduced by overexpression of mal2+. Dilutions shown were 10-fold starting with 104 cells. The mis12-537 strain was transformed with either the insertless vector (vector) or a plasmid expressing mal2+ from the thiamine-regulatable nmt1+ promoter (mal2+). Strains were grown for 22 h at 24°C in selective, thiamineless medium and then plated on selective EMM with (low-level expression) or without (high-level expression) thiamine and incubated at 24 or 35°C for 3 to 5 days. (B and C) Two-hybrid analysis of Mal2p and Mis12p protein-protein interaction. (B) Analysis of histidine expression. The fusion constructs containing the DNA-binding domain of GAL4 (BD) or the transcriptional activation domain of Gal4 (AD) were coexpressed. Growth on SD/-Trp, -Leu, -His medium containing 5 or 10 mM 3-AT is shown. As controls, coexpressions of corresponding fusion proteins with the appropriate two-hybrid vector containing no insert are shown. (C) lacZ analysis. Per strain, 104 cells pregrown in selective medium were spotted on an SD/-Trp, -Leu plate, incubated at 30°C for 24 h, and overlaid with X-Gal mixture containing top agarose to observe β-galactosidase activity. The plate shown was incubated for 8 h at 30°C. A dark color indicates interaction.

The interaction between these two centromere proteins raised the question whether the centromere localization of Mal2p is dependent on the presence of a functional Mis12p or vice versa. The localization of the Mal2-GFPp fusion protein was examined in growing mis12-537 cells incubated at the permissive (24°C) and nonpermissive (36°C) temperatures. In both cases, the Mal2-GFPp signals remained unchanged and colocalized with the centromere even after prolonged incubation at 36°C (data not shown). Thus localization of Mal2p does not appear to be dependent on a functional mis12+ gene product. We also asked if localization of Mis12p was dependent on the presence of a functional Mal2p protein by expressing GFP-tagged mis12+ (27) in a mal2-1 strain. The Mis12p fusion protein in the mal2-1 strain showed an identical localization regardless of the incubation temperatures (24 and 35°C) used, indicating that the presence of Mis12p at centromeres is not dependent on a functional Mal2p protein (data not shown).

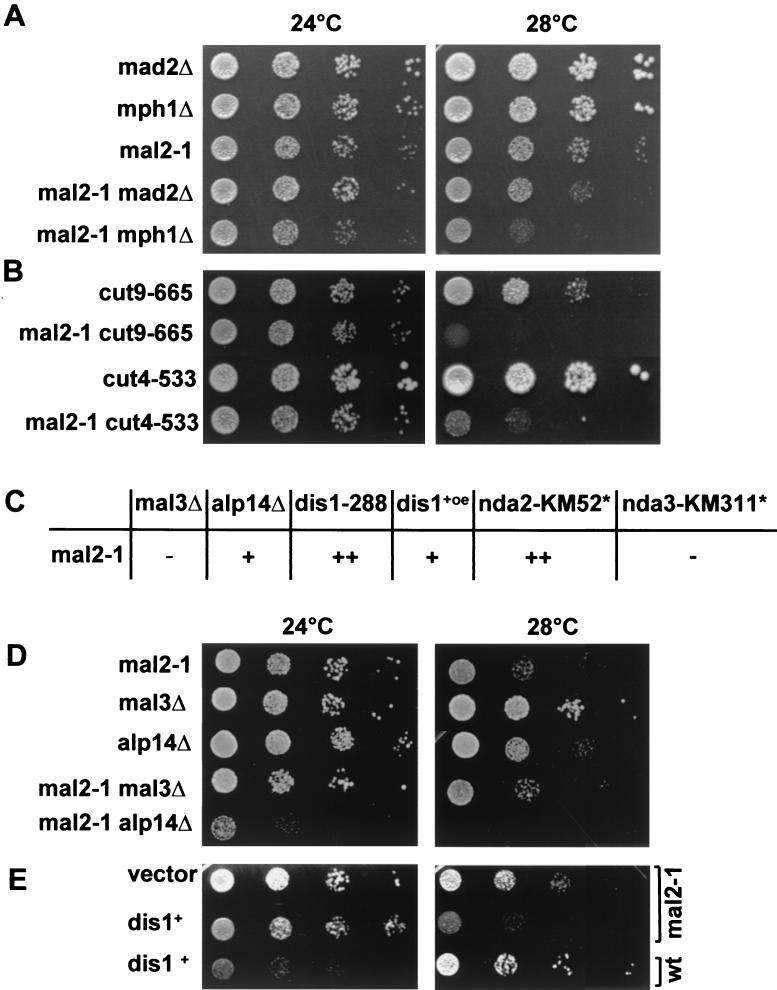

mal2-1 shows genetic interactions with the spindle checkpoint mutants mph1Δ and mad2Δ.

mal2-1 cells are hypersensitive to microtubule-destabilizing drugs, and the mal2-1 allele was synthetically lethal in combination with a mutant α-tubulin allele (19). However, since spindle formation and elongation were seemingly not affected in the mal2-1 mutant (reference 19 and data not shown), we asked if the spindle checkpoint, which monitors the correct alignment of chromosomes on the spindle (reviewed in reference 26), was activated in mal2-1 cells. We therefore constructed double-mutant strains of mal2-1 with null alleles of mad2+ and mph1+, which are evolutionarily conserved components of the spindle checkpoint pathway (31, 32). We found that the mal2-1 mad2Δ and mal2-1 mph1Δ of double-mutant strains both showed reduced growth compared to the single-mutant strains at 28°C (semipermissive temperature for mal2-1), although growth of the mal2-1 mph1Δ strain was affected more severely (Fig. 8A). This implies that the spindle checkpoint is activated in mal2-1 cells. Since there are no visible spindle defects, it is possible that the connection between mitotic spindle microtubules and the kinetochores is affected. Entry into anaphase was slightly delayed in synchronized mal2-1 cells compared to wild-type cells (data not shown). This delay was probably caused by a transient activation of the spindle checkpoint since these cells eventually progressed through mitosis, giving rise to aberrant separation of the chromatin.

FIG. 8.

mal2-1 interacts genetically with the spindle checkpoint pathway, the APC, and components of the spindle. (A) Serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) show growth of mad2Δ, mph1Δ, and mal2-1 single mutants and mal2-1 mad2Δ and mal2-1 mph1Δ double mutants at 24 and 28°C on rich medium for 5 days. (B) Serial dilution patch tests show the growth of cut9-665 and cut 4-533 single mutants and cut9-665 mal2-1 and cut4-533 mal2-1 double mutants at 24 and 28°C on rich medium for 4 days. (C) Double-mutant strains of mal2-1 with mutant alleles of genes coding for spindle components were constructed by tetrad analysis at 24°C, and the growth behavior of the double-mutant strains was compared to the growth of the single-mutant strains. −, no genetic interaction observed;+, genetic interaction observed; ++, synthetic lethal; ∗, data from reference 19. (D) Serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of mal2-1, mal3Δ, and alp14Δ single-mutant strains and mal2-1 and mal3Δ and mal2-1 alp14Δ double-mutant strains grown at 24 and 28°C for 4 to 5 days on rich medium. (E) Plasmid-borne expression of dis1+-GFP from the wild-type dis1+ promoter in mal2-1 and wild-type strains grown on selective medium at 24 or 28°C for 5 days.

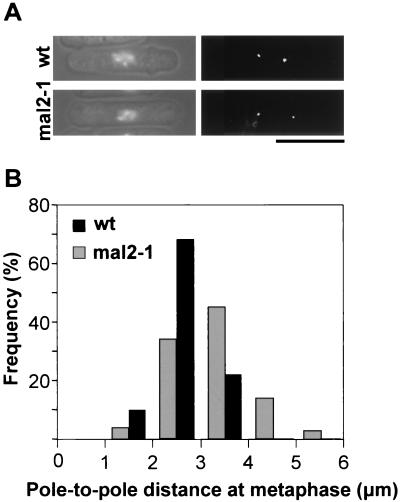

Expansion of the metaphase spindle in mal2-1 mutant cells.

Although bipolar spindle formation, elongation, and movements were apparently normal in mal2-1 cells, it has been shown that metaphase spindle length is affected in strains carrying mutations in centromere proteins associated with the inner centromeric region (27). To analyze metaphase spindle length in mal2-1 cells, G1-synchronized cells expressing a tagged version of the spindle pole body component Cut12p (9) were released into the cell cycle at 35°C. DAPI staining showed that metaphase cells were found predominantly at the 5.5-h time point, and thus the length of the metaphase spindle was determined in these cells by measuring the pole-to-pole distance between the separated spindle pole bodies visualized by GFP-tagged Cut12p (Fig. 9). The average length of the metaphase spindle in mal2-1 cells was found to be 3.15 ± 0.87 μm, while that in wild-type cells was 2.81 ± 0.48 μm (P < 0.0008 for the two values in the t test), indicating that the presence of the mal2-1 allele caused a 12% increase in the length of the metaphase spindle.

FIG. 9.

The metaphase spindle is extended in mal2-1 cells. (A) mal2-1 and wild-type (wt) cells were synchronized as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. Five hours after release into rich medium at 35°C, the cells were fixed and stained with DAPI to identify metaphase cells. The spindle pole bodies were visualized by GFP-tagged Cut12p. (B) Distribution of metaphase spindle length in mal2-1 and wild-type cells. The pole-to-pole distances of more than 100 metaphase cells were determined for each strain and are presented diagrammatically.

To confirm that the metaphase spindle in mal2-1 cells was longer than normal, we also measured the spindle length in cells arrested in metaphase by overexpression of Mph1p (see Materials and Methods). In this case, the mal2-1 metaphase spindles were 36% longer than those of wild-type cells (3.56 ± 0.90 μm versus 2.62 ± 0.71 μm; P = 0.0001).

mal2-1 genetically interacts with the APC.

We also attempted to arrest mal2-1 cells in metaphase by constructing double mutants with two genes that encode components of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC)/cyclosome. The Cut9p protein is a subunit of the APC that is required for the proteolytic destruction of specific cell cycle proteins to allow entry into anaphase (67). The mal2-1 cut9-665 double mutant showed a severe growth defect at 28°C (Fig. 8B). Genetic interactions between mal2-1 and the APC were further determined by constructing a double mutant between mal2-1 and cut4-533, which codes for a defective subunit of the APC (68). This double-mutant strain also showed severe growth inhibition compared to the single-mutant strains (Fig. 8B), indicating genetic interactions of mal2+ with components of the APC.

Genetic interaction between mal2-1 and microtubule-associated proteins.

The observations that mal2-1 cells are hypersensitive to microtubule poisons, have an activated spindle checkpoint, and are synthetically lethal in combination with a mutant α-tubulin allele suggest that the Mal2p protein might play a role in the interaction between spindle microtubules and the centromere. Furthermore, 16.8% of all mal2-1 anaphase cells showed lagging chromosomes on anaphase spindles when grown at the restrictive temperature (data not shown), indicating a possible defect in the proper centromere-microtubule interaction. We therefore analyzed genetic interactions between mal2-1 and genes encoding three components of the mitotic spindle: Mal3p, Dis1p, and Alp14p/Mtc1p (7, 24, 44, 46). Mal3p is the fission yeast homolog of the EB1 protein, which has been localized to the plus ends of kinetochore microtubules and is implicated in the attachment of microtubule ends to the kinetochore (reviewed in references 20 and 59). The Dis1p and Alp14/Mtc1p proteins are members of the evolutionarily conserved ch-TOG/XMAP215 family that play a role in plus-end microtubule stability (25, 63, 65). In addition, Dis1p and Alp14p/Mtc1p appear to be associated in a cell cycle stage-specific manner with fission yeast centromeres (24, 46). We constructed double-mutant strains of mal2-1 with null alleles of mal3+ and alp14+ and a cold-sensitive dis1-288 allele (7, 24, 44). We found that the mal2-1 mal3Δ double-mutant strain showed no difference in growth compared to the mal2-1 single-mutant strain (Fig. 8C and D). However, the mal2-1 alp14Δ double-mutant strain showed severely reduced growth compared to the single-mutant strains at 24°C and was unable to grow at 28°C (Fig. 8D). In addition, the number of lagging anaphase chromosomes in the double mutant was increased by 37% compared to the mal2-1 single mutant (data not shown).

Tetrad analysis of the cross between the mal2-1 and dis1-288 strains revealed a strong genetic interaction since spores carrying both mutations were inviable (Fig. 8C) (see Materials and Methods for details). Furthermore, plasmid-borne expression of a Dis1-GFPp fusion protein expressed from the dis1+ promoter gave rise to synthetic dosage lethality in a mal2-1 strain grown at 28°C (Fig. 8E).

DISCUSSION

Mal2p was originally identified as an essential nuclear fission yeast protein for genome stability (19). The conditionally lethal temperature-sensitive mal2-1 allele gave rise to increased loss of a minichromosome at the permissive temperature and led to severe missegregation of endogenous chromosomes under restrictive conditions. However, the exact role of Mal2p in chromosome segregation remained unclear.

In this study, we showed that Mal2p is a new component of the fission yeast centromere and that it displays unique features in the regulation of a functional centromere. In vivo localization of a Mal2p fusion protein showed a localization pattern as observed for fission yeast centromere proteins (14, 27, 54) and indicated an association of Mal2p with the centromere throughout the cell cycle (Fig. 3). ChIP analysis demonstrated a specific association of Mal2p with the central core region of the centromere DNA (Fig. 4). The importance of the central core region plus some flanking sequence in the formation of a functional mitotic centromere has been demonstrated using a minichromosome assay system (6). Our data demonstrate that Mal2p is required to maintain the specialized chromatin structure of this region (Fig. 6), which is essential for centromere function (12).

We tested if Mal2p interacted with other proteins which associate with the inner centromere region. Only a few inner core centromere proteins have been identified to date. Mis6p and Mis12p, like Mal2p, were identified in a screen for mutants that affect genome stability, while SpCENP-A is a homolog of the mammalian histone H3 variant CENP-A (27, 40, 54, 57). Mis6p and Mis12p do not appear to associate in vivo since they do not coimmunoprecipitate or cosediment (27). The centromeric localization of CENP-A appears to be Mis6p dependent (57). We found that mal2+ interacted strongly with mis12+ but not with mis6+ in a synthetic dosage lethality assay (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Furthermore, Mal2p and Mis12p interacted in a two-hybrid assay, suggesting that the mal2+ and mis12+ gene products might function in the same centromeric protein complex.

The inner centromere proteins identified to date appear to be conserved in evolution since proteins with sequence similarities have been identified as components of the kinetochore in budding yeast and/or vertebrate cells (28, 42, 47, 54, 55). The Mal2p amino acid sequence shows no strong sequence similarity to other proteins in the database except for a limited identity to Mcm21 (25.9% identity in an 81-amino-acid stretch), an S. cerevisiae nonessential centromere component, that in a complex with the Ctf19 and Okp1 proteins physically links various centromere complexes (48). To test if Mal2p and Mcm21 are functional homologs, we attempted to rescue the nongrowth phenotype of the mal2-1 strain at the restrictive temperature by overexpression of MCM21 cDNA (48). Under the conditions used in this experiment, we were unable to suppress the mal2-1 nongrowth phenotype (data not shown). It is thus unclear if Mal2p and Mcm21 are functional homologs. Furthermore, proteins with sequence similarity to the Ctf19 and Okp1 proteins complexed with Mcm21 in budding yeast do not appear to exist in fission yeast.

Proteins associated with the inner centromere region are necessary for the establishment and maintenance of the specific chromatin architecture of this region (27, 54) (Fig. 6). In addition, Mal2p is specifically required for transcriptional silencing of genes placed within the central core region of the centromere since loss of functional Mal2p strongly alleviated the silencing of this region (Fig. 5). Furthermore, although Mal2p also associates with the inner centromere repeats, the mal2-1 mutation showed no effect on transcriptional silencing of the ura4+ marker placed within this region. Similar results have been obtained for the Mis6p centromere protein, which associates with the central core and inner repeats but specifically affects transcriptional silencing within the central core region only (49). Interestingly, the mal2-1 mutation actually enhanced silencing at the outer centromere repeats (Fig. 5). Mal2p is thus the first inner centromere protein that affects transcriptional silencing within the outer repeats.

Mal2p also plays a role in regulating the metaphase spindle length since mal2-1 cells exibit longer-than-wild-type metaphase spindles (Fig. 9). This might possibly reflect altered pulling forces or a more general defect in spindle morphogenesis (27). Spindle expansion has also been observed for strains expressing mutant versions of the mis6+ and mis12+ genes (27). While all three mutant strains show a defect in the biorientation of sister centromeres in the spindle, the daughter nuclei in mis12 and mis6 mutant anaphase cells were always fully separated (27, 54) (Fig. 2). This is in contrast to the phenotype of mitotic mal2-1 cells, where we observed a significant proportion of lagging chromosomes on an elongated anaphase spindle. This phenotype possibly indicates a loss of spindle pulling forces and an involvement of Mal2p in the connection between the centromere and spindle microtubules. In this context, it is noteworthy that mal2-1 cells showed an altered sensitivity to benzimidazole compounds that destabilize microtubules and that mal2-1 is synthetically lethal with a mutant allele of α-tubulin (19). Interestingly, elevated sensitivity to microtubule inhibitors, a synergistic interaction with a mutant tubulin allele, and lagging chromosomes have also been described for the rik1, clr4, and swi6 mutants (15). However, in contrast to Mal2p, these chromodomain proteins associate with the outer centromeric repeat (reviewed in reference 50).

In the present study, we found that an intact spindle checkpoint, which monitors the correct alignment of chromosomes on the spindle, is required for proper growth of mal2-1 cells at the semipermissive temperature (Fig. 8A). In addition, double mutants of mal2-1 with mutant alleles of genes encoding APC/cyclosome components were synthetically lethal (Fig. 8B). This might be caused by the inhibitory effect of the activated spindle checkpoint on the APC (reviewed in reference 26).

To determine if the Mal2p protein might play a role in the association of centromere and spindle microtubules, we assayed the genetic interaction between mal2+ and components of the spindle that have been implicated in this process. To this end, double mutants of mal2-1 with mutant versions of mal3+, dis1+, and mtc1+/alp14+ were constructed. Absence of mal3+ leads to increased chromosome loss and lagging chromosomes under specific conditions (7; C. Decker and U. Fleig, unpublished data). The human homolog of Mal3p, EB1, is required for the interaction between the kinetochore and microtubules (20, 36, 37). The fission yeast Dis1p and the Mtc1p/Alp14p proteins belong to the conserved TOG/XMAP215 family, which regulates microtubule dynamics as plus-end microtubule-stabilizing factors (24, 44, 46; reviewed in reference 3). Dis1p, which has been implicated in the balance of forces in the metaphase spindle, and Mtc1p/Alp14p are associated with spindle microtubules and are associated with centromeres in a cell cycle-specific manner (24, 45, 46). It has been proposed that these proteins play a role in connecting the centromere and spindle microtubules.

The mal2-1 mal3Δ double-mutant strain showed no difference in growth compared to the single-mutant strains. In contrast, a combination of MCM21 and BIM1 null alleles (coding for the putative Mal2p homolog and the Mal3p homolog in S. cerevisiae, respectively) has been shown to be inviable (62).

However, strong genetic interaction was observed between mal2-1 and the genes encoding the fission yeast XMAP215. The mal2-1 alp4Δ double-mutant strain showed severe growth inhibition and a 37% increase in the number of lagging anaphase chromosomes, while the mal2-1 dis1-288 double-mutant strain was synthetically lethal (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, plasmid-borne expression of wild-type dis1+ in mal2-1 led to synthetic dosage lethality at the semipermissive temperature (Fig. 8E). The synergistic interaction between mal2-1 and mutant alleles of genes encoding XMAP215 homologs supports the proposal that Mal2p plays a role in the interaction between kinetochore microtubules and the centromere. Interestingly, genetic interaction between mutant alleles of mis12+ but not mis6+ and dis1+ or mtc1+/alp14+ has been observed also (27, 46) strengthening the suggestion that Mal2p and Mis12p might operate in the same protein complex.

The complex structure of the fission yeast centromere is more reminiscent of the centromeres of higher eucaryotes than those of S. cerevisiae, and different proteins associate with distinct domains of the fission yeast centromere DNA. We have identified a new essential protein, Mal2p, that interacts specifically with the central core of the centromere DNA, affects the chromatin structure and the transcriptional silencing of this region, and thus plays an essential role in building up a functional fission yeast centromere. In addition, phenotypic analysis and genetic evidence point to a role of Mal2p in the connection between kinetochore microtubules and the centromere.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Shelley Sazer for her careful reading of the manuscript. We thank Mitsuhiro Yanagida, Iain Hagan, Shelley Sazer, Takashi Toda, and Kazuo Tatebayashi for strains; Sabine Klein for FACS analysis; Inga Müller for the mal2+-GFP strain; Yamei Wang and Christoph Beuter for help with Fig. 5, 6, and 7; Keith Gull for the TAT1 antibody; Johannes Lechner for MCM21; and Louise Clarke, Mary Baum, Andreas Düsterhöft, and Takashi Toda for DNA probes. Special thanks to Johannes Hegemann for support.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (HE1383/7-2 and FL168/2-3 to U.F.), the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Stiftung (to Q.-W. J.), the Medical Research Council of Great Britain (to R.C.A.), and the Association for International Cancer Research (to A.L.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allshire, R. C., J. P. Javerzat, N. J. Redhead, and G. Cranston. 1994. Position effect variegation at fission yeast centromeres. Cell 76:157-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allshire, R. C., E. R. Nimmo, K. Ekwall, J. P. Javerzat, and G. Cranston. 1995. Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains in fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 9:218-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen, S. S. 2000. Spindle assembly and the art of regulating microtubule dynamics by MAPs and Stathmin/Op18. Trends Cell Biol. 10:261-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahler, J., J. Q. Wu, M. S. Longtine, N. G. Shah, A. McKenzie III, A. B. Steever, A. Wach, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14:943-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannister, A. J., P. Zegerman, J. F. Partridge, E. A. Miska, J. O. Thomas, R. C. Allshire, and T. Kouzarides. 2001. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410:120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum, M., V. K. Nagan, and L. Clarke. 1994. The centromeric K-type repeat and the central core are together sufficient to establish a functional Schizosaccharomyces pombe centromere. Mol. Biol. Cell 5:747-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beinhauer, J. D., I. M. Hagan, J. H. Hegemann, and U. Fleig. 1997. Mal3, the fission yeast homologue of the human APC-interacting protein EB-1 is required for microtubule integrity and the maintenance of cell form. J. Cell Biol. 139:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard, P., J. F. Maure, J. F. Partridge, S. Genier, J. P. Javerzat, and R. C. Allshire. 2001. Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science 294:2539-2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridge, A. J., M. Morphew, R. Bartlett, and I. M. Hagan. 1998. The fission yeast SPB component Cut12 links bipolar spindle formation to mitotic control. Genes Dev. 12:927-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chikashige, Y., N. Kinoshita, Y. Nakaseko, T. Matsumoto, S. Murakami, O. Niwa, and M. Yanagida. 1989. Composite motifs and repeat symmetry in S. pombe centromeres: direct analysis by integration of NotI restriction sites. Cell 57:739-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke, L. 1998. Centromeres: proteins, protein complexes, and repeated domains at centromeres of simple eukaryotes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 8:212-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke, L., M. Baum, L. G. Marschall, V. K. Ngan, and N. C. Steiner. 1993. Structure and function of Schizosaccharomyces pombe centromeres. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 58:687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Csink, A. K., and S. Henikoff. 1998. Something from nothing: the evolution and utility of satellite repeats. Trends Genet. 14:200-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekwall, K., J. P. Javerzat, A. Lorentz, H. Schmidt, G. Cranston, and R. Allshire. 1995. The chromodomain protein Swi6: a key component at fission yeast centromeres. Science 269:1429-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekwall, K., E. R. Nimmo, J. P. Javerzat, B. Borgstrom, R. Egel, G. Cranston, and R. Allshire. 1996. Mutations in the fission yeast silencing factors clr4+ and rik1+ disrupt the localisation of the chromo domain protein Swi6p and impair centromere function. J. Cell Sci. 109:2637-2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekwall, K., T. Olsson, B. M. Turner, G. Cranston, and R. C. Allshire. 1997. Transient inhibition of histone deacetylation alters the structural and functional imprint at fission yeast centromeres. Cell 91:1021-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekwall, K., and J. F. Partridge. 1999. Fission yeast chromosome analysis: Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP), p. 39-57. In W. A. Bickmore (ed.), Chromosome structure analysis, a practical approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 18.Fishel, B., H. Amstutz, M. Baum, J. Carbon, and L. Clarke. 1988. Structural organization and functional analysis of centromeric DNA in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:754-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleig, U., M. Sen-Gupta, and J. H. Hegemann. 1996. Fission yeast mal2+ is required for chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6169-6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fodde, R., J. Kuipers, C. Rosenberg, R. Smits, M. Kielman, C. Gaspar, J. H. van Es, C. Breukel, J. G. Wiegant, R. H., and H. Clevers. 2001. Mutations in the APC tumour suppressor gene cause chromosomal instability. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:433-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fromont-Racine, M., J. C. Rain, and P. Legrain. 1997. Toward a functional analysis of the yeast genome through exhaustive two-hybrid screens. Nat. Genet. 16:277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funabiki, H., I. Hagan, S. Uzawa, and M. Yanagida. 1993. Cell cycle-dependent specific positioning and clustering of centromeres and telomeres in fission yeast. J. Cell Biol. 121:961-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuya, K., K. Takahashi, and M. Yanagida. 1998. Faithful anaphase is ensured by Mis4, a sister chromatid cohesion molecule required in S phase and not destroyed in G1 phase. Genes Dev. 12:3408-3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia, M. A., L. Vardy, N. Koonrugsa, and T. Toda. 2001. Fission yeast ch-TOG/XMAP215 homologue Alp14 connects mitotic spindles with the kinetochore and is a component of the Mad2-dependent spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 20:3389-3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gard, D. L., and M. W. Kirschner. 1987. A microtubule-associated protein from Xenopus eggs that specifically promotes assembly at the plus-end. J. Cell Biol. 105:2203-2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner, R. D., and D. J. Burke. 2000. The spindle checkpoint: two transitions, two pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 10:154-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goshima, G., S. Saitoh, and M. Yanagida. 1999. Proper metaphase spindle length is determined by centromere proteins Mis12 and Mis6 required for faithful chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 13:1664-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goshima, G., and M. Yanagida. 2000. Establishing biorientation occurs with precocious separation of the sister kinetochores, but not the arms, in the early spindle of budding yeast. Cell 100:619-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagan, I., and M. Yanagida. 1995. The product of the spindle formation gene sad1+ associates with the fission yeast spindle pole body and is essential for viability. J. Cell Biol. 129:1033-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagan, I. M., and J. S. Hyams. 1988. The use of cell division cycle mutants to investigate the control of microtubule distribution in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 89:343-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He, X., M. H. Jones, M. Winey, and S. Sazer. 1998. Mph1, a member of the Mps1-like family of dual specificity protein kinases, is required for the spindle checkpoint in S. pombe. J. Cell Sci. 111:1635-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He, X, T. E. Patterson, and S. Sazer. 1997. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe spindle checkpoint protein Mad2p blocks anaphase and genetically interacts with the anaphase-promoting complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7965-7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiraoka, Y., T. Toda, and M. Yanagida. 1984. The NDA3 gene of fission yeast encodes beta-tubulin: a cold-sensitive nda3 mutation reversibly blocks spindle formation and chromosome movement in mitosis. Cell 39:349-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irelan, J. T., G. I. Gutkin, and L. Clarke. 2001. Functional redundancies, distinct localizations and interactions among three fission yeast homologs of centromere protein-B. Genetics 157:1191-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James, P., J. Halladay, and E. A. Craig. 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144:1425-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juwana, J. P., P. Henderikx, A. Mischo, A. Wadle, N. Fadle, K. Gerlach, J. W. Arends, H. Hoogenboom, M. Freudschuh, and C. Renner. 1999. EB/RP gene family encodes tubulin binding proteins. Int. J. Cancer 81:275-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan, K. B., A. A. Burds, J. R. Swedlow, S. S. Bekir, P. K. Sorger, and I. S. Nathke. 2001. A role for the adenomatous polyposis coli protein in chromosome segregation. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:429-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinoshita, N., M. Goebl, and M. Yanagida. 1991. The fission yeast dis3+ gene encodes a 110-kDa essential protein implicated in mitotic control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:5839-5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitagawa, K., and P. Hieter. 2001. Evolutionary conservation between budding yeast and human kinetochores. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:678-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kniola, B., E. O'Toole, J. R. McIntosh, B. Mellone, R. Allshire, S. Mengarelli, K. Hultenby, and K. Ekwall. 2001. The domain structure of centromeres is conserved from fission yeast to humans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2767-2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroll, S. E., K. M. Hyland, P. Hieter, and J. J. Li. 1996. Establishing genetic interactions by a synthetic dosage lethality phenotype. Genetics 143:92-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Measday, V., D. W. Hailey, I. Pot, S. A. Givan, K. M. Hyland, G. Cagney, S. Fields, T. N. Davis, and P. Hieter. 2002. Ctf3p, the Mis6 budding yeast homolog, interacts with Mcm22p and Mcm16p at the yeast outer kinetochore. Genes Dev. 16:101-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moreno, S., A. Klar, and P. Nurse. 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194:795-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nabeshima, K., H. Kurooka, M. Takeuchi, K. Kinoshita, Y. Nakaseko, and M. Yanagida. 1995. p93dis1, which is required for sister chromatid separation, is a novel microtubule and spindle pole body-associating protein phosphorylated at the Cdc2 target sites. Genes Dev. 9:1572-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nabeshima, K., T. Nakagawa, A. F. Straight, A. Murray, Y. Chikashige, Y. M. Yamashita, Y. Hiraoka, and M. Yanagida. 1998. Dynamics of centromeres during metaphase-anaphase transition in fission yeast: Dis1 is implicated in force balance in metaphase bipolar spindle. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:3211-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakaseko, Y., G. Goshima, J. Morishita, and M. Yanagida. 2001. M phase-specific kinetochore proteins in fission yeast. Microtubule-associating Dis1 and Mtc1 display rapid separation and segregation during anaphase. Curr. Biol. 11:537-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishihashi, A., T. Haraguchi, Y. Hiraoka, T. Ikemura, V. Regnier, H. Dodson, W. C. Earnshaw, and T. Fukagawa. 2002. CENP-1 is essential for centromere function in vertebrate cells. Dev. Cell 2:463-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ortiz, J., O. Stemmann, S. Rank, and J. Lechner. 1999. A putative protein complex consisting of Ctf19, Mcm21, and Okp1 represents a missing link in the budding yeast kinetochore. Genes Dev. 13:1140-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Partridge, J. F., B. Borgstrom, and R. C. Allshire. 2000. Distinct protein interaction domains and protein spreading in a complex centromere. Genes Dev. 14:783-791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pidoux, A. L., and R. C. Allshire. 2000. Centromeres: getting a grip of chromosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:308-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pidoux, A. L., S. Uzawa, P. E. Perry, W. Z. Cande, and R. C. Allshire. 2000. Live analysis of lagging chromosomes during anaphase and their effect on spindle elongation rate in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 113:4177-4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Polizzi, C., and L. Clarke. 1991. The chromatin structure of centromeres from fission yeast: differentiation of the central core that correlates with function. J. Cell Biol. 112:191-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rea, S., F. Eisenhaber, D. O'Carroll, B. D. Strahl, Z. W. Sun, M. Schmid, S. Opravil, K. Mechtler, C. P. Ponting, C. D. Allis, and T. Jenuwein. 2000. Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature. 406:593-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saitoh, S., K. Takahashi, and M. Yanagida. 1997. Mis6, a fission yeast inner centromere protein, acts during G1/S and forms specialized chromatin required for equal segregation. Cell 90:131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stoler, S., K. C. Keith, K. E. Curnick, and M. Fitzgerald Hayes. 1995. A mutation in CSE4, an essential gene encoding a novel chromatin-associated protein in yeast, causes chromosome nondisjunction and cell cycle arrest at mitosis. Genes Dev. 9:573-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Su, S. Y., and M. Yanagida. 1997. The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, p. 765-826. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 57.Takahashi, K., E. S. Chen, and M. Yanagida. 2000. Requirement of Mis6 centromere connector for localizing a CENP-A-like protein in fission yeast. Science 288:2215-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi, K., S. Murakami, Y. Chikashige, H. Funabiki, O. Niwa, and M. Yanagida. 1992. A low copy number central sequence with strict symmetry and unusual chromatin structure in fission yeast centromere. Mol. Biol. Cell 3:819-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tirnauer, J. S., and B. E. Bierer. 2000. EB1 Proteins regulate microtubule dynamics, cell polarity, and chromosome stability. J. Cell Biol. 149:761-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toda, T., Y. Adachi, Y. Hiraoka, and M. Yanagida. 1984. Identification of the pleiotropic cell division cycle gene NDA2 as one of two different alpha-tubulin genes in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cell 37:233-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomonaga, T., K. Nagao, Y. Kawasaki, K. Furuya, A. Murakami, J. Morishita, T. Sutani, S. E. Kearsey, F. Uhlmann, K. Nasmyth, and M. Yanagida. 2000. Characterization of fission yeast cohesion: essential anaphase proteolysis of Rad21 phosphorylated in the S phase. Genes Dev. 21:2757-2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tong, A. H., M. Evangelista, A. B. Parsons, H. Xu, G. D. Bader, N. Page, M. Robinson, S. Raghibizadeh, C. W. Hogue, H. Bussey, B. Andrews, M. Tyers, and C. Boone. 2001. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294:2364-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tournebize, R., A. Popov, K. Kinoshita, A. J. Ashford, S. Rybina, A. Pozniakovsky, T. U. Mayer, C. E. Walczak, E. Karsenti, and A. A. Hyman. 2000. Control of microtubule dynamics by the antagonistic activities of XMAP215 and XKCM1 in Xenopus egg extracts. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uzawa, S., and M. Yanagida. 1992. Visualization of centromeric and nucleolar DNA in fission yeast by fluorescence in situ hybridization. J. Cell Sci. 101:267-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vasquez, R. J., D. L. Gard, and L. Cassimeris. 1994. XMAP from Xenopus eggs promotes rapid plus end assembly of microtubules and rapid microtubule polymer turnover. J. Cell Biol. 127:985-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woods, A., T. Sherwin, R. Sasse, T. H. MacRae, A. J. Baines, and K. Gull. 1989. Definition of individual components within the cytoskeleton of Trypanosoma brucei by a library of monoclonal antibodies. J. Cell Sci. 93:491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamada, H., K. Kumada, and M. Yanagida. 1997. Distinct subunit functions and cell cycle regulated phosphorylation of 20S APC/cyclosome required for anaphase in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 110:1793-1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamashita, Y. M., Y. Nakaseko, I. Samejima, K. Kumada, H. Yamada, D. Michaelson, and M. Yanagida. 1996. 20S cyclosome complex formation and proteolytic activity inhibited by the cAMP/PKA pathway. Nature 384:276-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]