Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of nurse led clinics in primary care on secondary prevention, total mortality, and coronary event rates after four years.

Design

Follow up of a randomised controlled trial by postal questionnaires and review of case notes and national datasets.

Setting

Stratified, random sample of 19 general practices in north east Scotland.

Participants

1343 patients (673 intervention and 670 control) under 80 years with a working diagnosis of coronary heart disease but without terminal illness or dementia and not housebound.

Intervention

Nurse led secondary prevention clinics promoted medical and lifestyle components of secondary prevention and offered regular follow up for one year.

Main outcome measures

Components of secondary prevention (aspirin, blood pressure management, lipid management, healthy diet, exercise, non-smoking), total mortality, and coronary events (non-fatal myocardial infarctions and coronary deaths).

Results

Mean follow up was at 4.7 years. Significant improvements were shown in the intervention group in all components of secondary prevention except smoking at one year, and these were sustained after four years except for exercise. The control group, most of whom attended clinics after the initial year, caught up before final follow up, and differences between groups were no longer significant. At 4.7 years, 100 patients in the intervention group and 128 in the control group had died: cumulative death rates were 14.5% and 18.9%, respectively (P=0.038). 100 coronary events occurred in the intervention group and 125 in the control group: cumulative event rates were 14.2% and 18.2%, respectively (P=0.052). Adjusting for age, sex, general practice, and baseline secondary prevention, proportional hazard ratios were 0.75 for all deaths (95% confidence intervals 0.58 to 0.98; P=0.036) and 0.76 for coronary events (0.58 to 1.00; P=0.049)

Conclusions

Nurse led secondary prevention improved medical and lifestyle components of secondary prevention and this seemed to lead to significantly fewer total deaths and probably fewer coronary events. Secondary prevention clinics should be started sooner rather than later.

What is already known on this topic

Several effective interventions exist for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease, but implementing them in practice has proved difficult

Secondary prevention programmes for coronary heart disease have improved short term outcomes such as processes of care and quality of life

What this study adds

Short term improvements in uptake of secondary prevention produced by nurse led clinics are maintained in the longer term

Improved medical and lifestyle components of secondary prevention produced by nurse led clinics seem to lead to fewer total deaths and coronary events

Introduction

People with pre-existing coronary heart disease are at particularly high risk of coronary events and death, but effective secondary prevention can reduce this risk. Effective secondary prevention comprises several elements. These include pharmaceutical interventions (for example, antiplatelet agents, statins, β blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors) and interventions to change behaviour and modify lifestyle (smoking cessation, regular exercise, and healthy diets).1 Most people with coronary disease are cared for in primary care, and general practitioners have been encouraged to target them for secondary prevention.2 This has proved difficult, however, and surveys of baseline provision consistently show that secondary prevention is suboptimal.3,4

Several attempts at multifactorial interventions to improve secondary prevention have now been evaluated. A recent systematic review of randomised trials concluded that programmes for disease management improved processes of care, reduced admissions to hospital, and enhanced quality of life.5 No impact on survival or coronary event rates was detected, however, probably because the median follow up of studies in the review was too short (one year). Evidence is now needed from longer term follow up studies on whether improvements in processes of care translate into reduced coronary event rates and mortality.

We conducted one of the randomised trials included in the recent systematic review, and our findings at one year were typical of the pooled results. We found that nurse led secondary prevention clinics in primary care improved medical and lifestyle components of secondary prevention (except smoking) and health related quality of life.6,7 In this follow up study, we aimed to evaluate whether these improvements were sustained after four years and to assess effects on total mortality and coronary event rates.

Methods

Participants

Details of recruitment, randomisation, and the intervention have been reported previously.6,7 Briefly, we recruited 1343 randomly selected patients with a working diagnosis of coronary heart disease, but without terminal illness or dementia and not housebound, from 19 randomly selected general practices in north east Scotland. Participants were randomised by NCC (by individual after stratification for age, sex, and practice) to intervention or control groups by using tables of random numbers.

Participants in the intervention group were invited to attend secondary prevention clinics at their general practice, during which their symptoms and treatment were reviewed, use of aspirin promoted, blood pressure and lipid management reviewed, lifestyle factors assessed, and, if appropriate, behavioural change negotiated. Follow up was according to clinical circumstances (every two to six months was advised in the protocol). Participants in the control group received usual care. After one year, we collected data on uptake of secondary prevention and participants' health. We fed back the findings to participating general practices, the staff of which decided their own policies on running clinics.

After four years we traced the original participants through their general practices or, for those who had moved within Scotland, through health board records. For those who had left Scotland, follow up ceased when their general practice case notes were transferred out of the country.

Outcome measures

The main outcomes were use of secondary prevention, total mortality, and coronary event rates. We collected data on uptake of components of secondary prevention before intervention, at one year, and after the fourth year. Final data collection was on a rolling basis over a 10 month period. We collected data on management of blood pressure and lipids by audit of general practice case notes, and we collected data on aspirin use, diet, smoking, and exercise by postal questionnaire. We assessed diet with the dietary instrument for nutrition education score, and we assessed smoking and exercise with the health practices index.8,9 Criteria used to define appropriate secondary prevention were aspirin taken (or contraindicated by allergy or peptic ulceration), blood pressure managed according to guidelines of the British Hypertension Society, lipids managed according to local guidelines for lipid management in general practices in Grampian region, moderate physical activity (index of physical activity >4), low fat diet (dietary instrument for nutrition education score <30), and not currently smoking.8–11

National guidelines on the management of blood pressure and lipids changed during the course of the study, but for consistency we used recommendations current at the start of the study throughout. Blood pressure was accepted as being managed according to British Hypertension Society recommendations if the last blood pressure measurement (recorded within three years) was less than 160/90 mm Hg or was receiving attention (treated, checked within three months, or patient attending a specialist clinic).10 Lipids were managed according to local guidelines for lipid management in general practices in Grampian region if the last measurement for cholesterol concentration (recorded within three years) was 5.2 mmol/l or less or was receiving attention (treated, checked within three months, or patient attending a specialist clinic).

We obtained data on dates and causes of deaths from the Information and Statistics Division for the NHS in Scotland. Coronary events were defined as coronary deaths or non-fatal myocardial infarctions. We collected data on non-fatal myocardial infarctions during review of general practice case notes (diagnosis of definite myocardial infarction in hospital discharge letters) and from hospital morbidity records held by the Information and Statistics Division for the NHS in Scotland. We ceased follow up of deaths and coronary events the date data were collected from the general practice case notes.

Sample size

The original trial was designed to detect differences in secondary prevention.7 A sample size of 1300 participants at baseline was projected to give at least 808 respondents, which would have 80% power to detect an absolute difference in uptake of any component of secondary prevention of 10%. The study's power to detect differences in mortality and coronary event rates was lower. Based on expected death and coronary event rates of 15% in the control group, our study had 75% power to detect a relative risk reduction of 33% at the 5% significance level.

Statistical analysis

We used standard statistical methods and SPSS for windows release 9.0.0. We hypothesised that patients attending secondary prevention clinics would have higher uptake of the six defined components of secondary prevention, fewer coronary events, and reduced total mortality. We analysed binary data on secondary prevention with logistic regression to adjust for age (in years), sex, general practice, and uptake of secondary prevention at baseline (binary variable indicating appropriate or not). For total mortality and coronary event data, we constructed Kaplan-Meier survival curves and analysed these with the log rank test. We used Cox regression for further analysis to adjust for age, general practice, sex, and uptake of secondary prevention at baseline. The main analysis was by intention to treat. We conducted a supplementary analysis of components of secondary prevention by length of exposure to clinics (time interval between each patient's first and most recent attendance at secondary prevention clinics).

Results

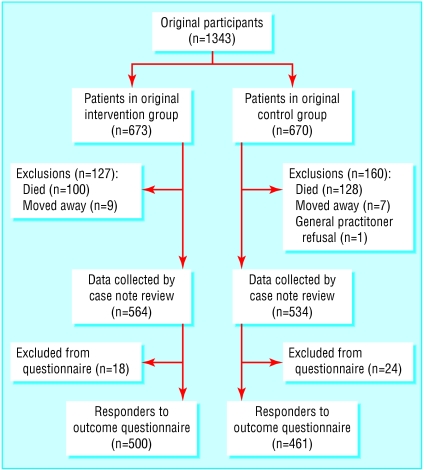

Mean follow up was 4.7 years. Of the 1343 original participants, 228 died and 16 had left Scotland (fig 1). We reviewed the case notes of the remaining 1099 except for one participant, whose new general practitioner refused follow up. Analysis of blood pressure and lipid management was complete for the remaining 1098 participants. Overall we excluded 42 participants from the postal questionnaire because of dementia or terminal illness. The questionnaire was completed by 961 of the remaining 1056 participants (91.0%). Intervention and control groups were well matched for age, sex, and practice characteristics at baseline and follow up (table 1).

Figure 1.

Study profile

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and exposure to nurse led secondary prevention clinics in intervention and control groups at baseline and at four years. Value are numbers (percentages) of participants unless stated otherwise

| Baseline

|

Four years

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group (n=673)

|

Control group (n=670)

|

Intervention group (n=564)

|

Control group (n=534)

|

||

| Men | 392 (58.2) | 390 (58.2) | 321 (57.0) | 286 (53.6) | |

| Mean (SD) age at 1 January 1995 | 66.1 (8.2) | 66.3 (8.2) | 65.4 (8.2) | 65.7 (8.6) | |

| Attend rural practice | 323 (48.0) | 319 (47.6) | 267 (47.3) | 244 (45.7) | |

| Size of practice: | |||||

| <5000 patients | 98 (14.6) | 103 (15.4) | 83 (14.7) | 82 (15.4) | |

| 5000-10 000 patients | 264 (39.2) | 259 (38.7) | 216 (38.3) | 196 (36.7) | |

| >10 000 patients | 311 (46.2) | 308 (46.0) | 264 (46.8) | 256 (48.0) | |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 310 (46.1) | 295 (44.0) | 264 (46.8) | 243 (45.5) | |

| Exposed to secondary prevention clinics: | |||||

| Never | 673 (100) | 670 (100) | 71 (12.6) | 238 (44.6) | |

| <1 year | — | — | 188 (33.3) | 110 (20.6) | |

| >1 year to 3 years | — | — | 135 (24.0) | 169 (316) | |

| >3 years | — | — | 170 (30.1) | 17 (3.2) | |

During the first year of the study, 551 of 673 (81.9%) participants in the intervention group attended a secondary prevention clinic at least once. By final follow up, 16 of the 19 general practices were running secondary prevention clinics. Table 1 shows the length of exposure of participants in both groups to secondary prevention clinics.

Secondary prevention

Significant improvements were shown in the intervention group in all components of secondary prevention except smoking at one year (table 2). At four years these improvements were sustained except for exercise. Differences with the control group were significant for all components except smoking at one year, but by four years the performance of the control group had improved and differences were no longer significant. In the supplementary analysis, longer exposure to clinics was associated with improved secondary prevention for aspirin use, blood pressure and lipid management, and exercise; diet and smoking status did not vary with length of exposure (table 3).

Table 2.

Number (percentage) of participants with appropriate secondary prevention at baseline, one year, and four years

| BaselineNo (%)

|

One year

|

Four years

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%)

|

Adjusted odds ratio* (95% CI)

|

No (%)

|

Adjusted odds ratio* (95% CI)

|

|||

| Aspirin management: | ||||||

| Intervention | 457/660 (69.2) | 466/575 (81.0) | 3.22 (2.15 to 4.80) | 396/486 (81.5) | 1.02 (0.71 to 1.47) | |

| Control | 413/659 (62.7) | 373/562 (66.4) | 1 | 348/446 (78.0) | 1 | |

| Blood pressure management: | ||||||

| Intervention | 585/673 (87.0) | 572/593 (96.5) | 5.32 (3.01 to 9.41) | 530/564 (94.0) | 1.48 (0.91 to 2.42) | |

| Control | 583/670 (87.0) | 510/580 (88.0) | 1 | 492/534 (92.1) | 1 | |

| Lipid management: | ||||||

| Intervention | 78/673 (11.6) | 244/593 (41.1) | 3.19 (2.39 to 4.26) | 325/564 (57.6) | 1.22 (0.93 to 1.58) | |

| Control | 90/670 (13.4) | 125/580 (21.6) | 1 | 284/534 (53.2) | 1 | |

| Moderate exercise: | ||||||

| Intervention | 241/663 (36.3) | 247/587 (42.1) | 1.67 (1.23 to 2.26) | 171/494 (34.6) | 1.26 (0.88 to 1.81) | |

| Control | 204/664 (30.7) | 177/568 (31.2) | 1 | 128/455 (28.1) | 1 | |

| Low fat diet: | ||||||

| Intervention | 287/597 (48.1) | 271/480 (56.5) | 1.47 (1.10 to 1.96) | 308/464 (66.4) | 0.74 (0.53 to 1.02) | |

| Control | 299/616 (48.5) | 226/465 (48.6) | 1 | 301/440 (68.4) | 1 | |

| Non-smoking: | ||||||

| Intervention | 545/668 (81.6) | 483/584 (82.7) | 0.78 (0.47 to 1.28) | 422/491 (86.0) | 0.73 (0.40 to 1.34) | |

| Control | 543/666 (81.5) | 481/568 (84.7) | 1 | 398/454 (87.7) | 1 | |

Adjusted for age, sex, baseline performance and general practice.

Table 3.

Adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios for appropriate secondary prevention by duration of exposure to clinics

| Component of secondary prevention

|

Years of clinic attendance

|

No (%)

|

Unadjusted odd ratios (95% CI)

|

P value*

|

Adjusted odds ratios† (95% CI)

|

P value*

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | None | 165/238 (69) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| <1 year | 200/250 (80) | 1.77 (1.17 to 2.68) | 2.06 (1.25 to 3.41) | |||

| >1 to 3 years | 237/275 (86) | 2.76 (1.78 to 4.28) | 2.75 (1.58 to 4.78) | |||

| >3 years | 144/171 (84) | 2.35 (1.44 to 3.87) | 2.56 (1.39 to 4.72) | |||

| Blood pressure management | None | 281/309 (91) | 1 | 0.021 | 1 | 0.008 |

| <1 year | 275/298 (92) | 1.19 (0.67 to 2.12) | 1.31 (0.69 to 2.46) | |||

| >1 to 3 years | 287/304 (94) | 1.68 (0.90 to 3.14) | 2.12 (1.05 to 4.29) | |||

| >3 years | 179/187 (96) | 2.23 (0.99 to 5.00) | 2.70 (1.12 to 6.53) | |||

| Lipid management | None | 122/309 (39) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| <1 year | 129/298 (43) | 1.17 (0.84 to 1.60) | 1.28 (0.88 to 1.85) | |||

| >1 to 3 years | 219/304 (72) | 3.95 (2.81 to 5.54) | 4.29 (2.87 to 6.42) | |||

| >3 years | 139/187 (74) | 4.44 (2.98 to 6.62) | 4.41 (2.75 to 7.10) | |||

| Exercise | None | 54/223 (24) | 1 | 0.005 | 1 | 0.030 |

| Up to 1 year | 71/240 (30) | 1.31 (0.87 to 1.99) | 1.34 (0.79 to 2.27) | |||

| >1 to 3 years | 86/255 (34) | 1.59 (1.07 to 2.38) | 1.66 (0.95 to 2.89) | |||

| >3 years | 59/163 (36) | 1.77 (1.14 to 2.76) | 1.89 (1.03 to 3.48) | |||

| Low fat diet | None | 158/228 (69) | 1 | 0.502 | 1 | 0.372 |

| Up to 1 year | 161/239 (67) | 0.91 (0.62 to 1.35) | 0.75 (0.48 to 1.19) | |||

| >1 to 3 years | 195/267 (73) | 1.20 (0.81 to 1.77) | 0.95 (0.59 to 1.55) | |||

| >3 years | 117/167 (70) | 1.04 (0.67 to 1.60) | 0.71 (0.41 to 1.22) | |||

| Non-smoking | None | 211/241 (88) | 1 | 0.115 | 1 | 0.285 |

| Up to 1 year | 202/250 (81) | 0.59 (0.36 to 0.98) | 0.55 (0.24 to 1.25) | |||

| >1 to 3 years | 250/279 (90) | 1.23 (0.71 to 2.11) | 1.67 (0.67 to 4.13) | |||

| >3 years | 155/172 (90) | 1.30 (0.69 to 2.43) | 1.27 (0.44 to 3.62) |

P value is for trend.

Adjusted for age, sex, baseline performance, and general practice.

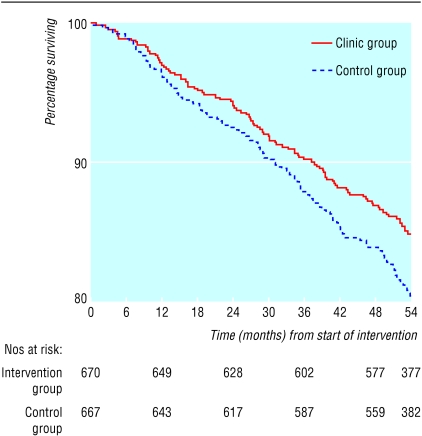

Total mortality

At follow up, 100 of 673 (14.9%) participants died in the intervention group compared with 128 of 670 (19.1%) in the control group. We performed a survival analysis to account for 16 individuals who left Scotland by censoring at time of loss to follow up (fig 2). After a mean follow up of 4.7 years, cumulative death rates were 14.5% for the intervention group and 18.9% for the control group (P=0.038), and the relative risk for total mortality was 0.78 (95% confidence interval 0.61 to 0.99). After adjustment for age, general practice, sex, and baseline secondary prevention, the proportional hazard ratio was 0.75 (0.58 to 0.98; P=0.036).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot for total mortality

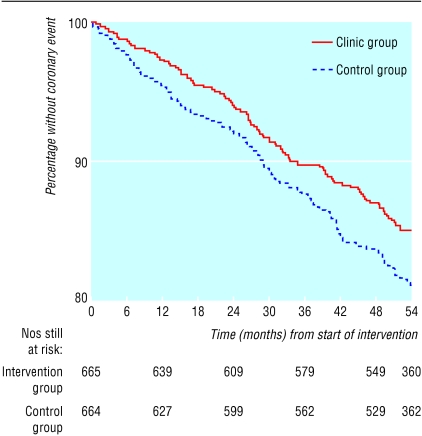

Coronary death or non-fatal myocardial infarction

At follow up the number of coronary deaths or non-fatal myocardial infarctions in the intervention group was 100 of 673 (14.9%) compared with 125 of 670 (18.7%) in the control group. With survival analysis (fig 3), cumulative event rates were 14.2% for the intervention group and 18.2% for the control group (P=0.052), and the relative risk for coronary events was 0.80 (0.63 to 1.01). After adjustment for age, general practice, sex, and baseline secondary prevention, the proportional hazard ratio was 0.76 (0.58 to 1.00; P=0.049).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot for coronary events (coronary death or non-fatal myocardial infarction)

Discussion

Nurse led secondary prevention clinics can improve secondary prevention within one year. In our study this translated into reduced mortality and reduced coronary event rates in the medium term. However, several factors need to be taken into consideration when interpreting our study.

The randomised trial on which our study is based was well conducted but had two main limitations: a relatively short follow up of one year and outcomes based on processes of care and risk factors.12–14 Our follow up study has remedied these limitations by extending follow up to more than four years and by evaluating effects on coronary events and mortality. The study was conducted with random samples of general practices and patients, few participants were lost to follow up, and response rates were good so findings should be generalisable at least locally.6,7 The main limitation of the study concerns crossover of participants from control to intervention and vice versa. Most patients in the control group attended at least one secondary prevention clinic after the original trial year. Our main analysis by intention to treat takes the most conservative approach and would be expected to reduce differences between groups. Indeed, at four years, uptake of secondary prevention in the control group had largely caught up with the intervention group. We conducted a secondary analysis of duration of exposure to clinics in which longer exposure to clinics was associated with better secondary prevention for the three medical components of secondary prevention and improved exercise. This finding is, however, observational. The differences could have been biased by the healthy attender effect, although we found no association between length of exposure to clinics and healthy diet or smoking habits. Caution is needed in interpreting our findings on mortality and coronary events because of the study's low power to detect differences in these outcomes and the borderline P values. However, this long term follow up was preplanned at the outset of the trial, and we collected and analysed data at a single preselected time point, which reduces the likelihood that our findings are due solely to chance.

The benefits we reported at one year were consistent with those found in several other trials of secondary prevention programmes—a systematic review of 12 randomised trials in a variety of settings concluded that they improved processes of care and risk factors.5 One trial included in the review, set in UK general practice, reported no benefits.15 It was, however, limited to patients after hospital admission for a cardiac event (in whom levels of secondary prevention were already good), so excluded most patients with coronary disease in general practice (in whom uptake of secondary prevention is lower).4 In a more recent randomised trial in Warwickshire, nurse led secondary prevention clinics were found to improve care by more than recall to general practitioners and audit with feedback.16 The main limitation with these and most previous studies, however, has been a too short follow up to detect effects on mortality or coronary event rates. In one randomised trial of health promotion to patients with angina in Belfast, total mortality at five years was similar to our study (13.7% and 18.8% in intervention and control groups, respectively) but numbers were smaller, so this difference was not significant.17,18

The benefits we found to total mortality and coronary events are consistent with projections we made prospectively based on the effects on secondary prevention after one year, in which we forecast risk reductions in the intervention group compared with the control group of 17% for coronary events and 15% for total mortality.19 They occurred despite improved secondary prevention in the control group after the original intervention year—although the survival curves seem to diverge over the four years, this visual impression should be treated with caution because of the study's low power. With this caveat, our findings are consistent with the expectation that benefits from secondary prevention continue to accrue over the medium term and show the value of attending clinics sooner rather than later.

It seems likely that the improvements in secondary prevention seen in the control group between one and four years were due, at least in part, to exposure to secondary prevention clinics. Results of the supplementary analysis, by length of exposure to clinics, support this view, since for most components of secondary prevention longer exposure to clinics was associated with better secondary prevention. However, there was no association between exposure to clinics and healthier diets despite the clinics seeming to improve diet during the first year. This needs explanation and may be related to changes in the clinic protocol made by most of the practices. In particular, most practices had reduced the frequency of clinic attendance to once a year, which is probably insufficient to promote and maintain change in lifestyle.

Acknowledgments

We thank staff at all the general practices who participated in the study, especially the health visitors, practice nurses, and district nurses who ran the clinics. Participating general practices were Aboyne Medical Practice, Ardach Practice, Dr Crowley, Danestone Medical Practice, Elmbank Group, Dr Grieve and Partners, Kemnay Medical Practice, Kincorth Medical Practice, King Street Medical Practice, The Laich Medical Practice, Dr Mobbs and Partners, Drs Mackie and Kay, Old Machar Medical Practice, Rubislaw Medical Group, Seafield Medical Practice, Skene Medical Practice, Spa-Well Medical Group, Turriff Medical Practice, and Victoria Street Medical Group.

Footnotes

Funding: Chief Scientist Office at the Scottish Executive.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN guideline number 51: management of stable angina—a national clinical guideline. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. National service framework for coronary heart disease. London: DoH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.EUROASPIRE II Study Group. Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries; principal results from EUROASPIRE II Euro Heart Survey Programme. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:554–572. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell NC, Thain J, Deans HG, Ritchie LD, Rawles JM. Secondary prevention in coronary heart disease: baseline survey of provision in general practice. BMJ. 1998;316:1430–1434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7142.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAlister FA, Lawson FME, Teo KK, Armstrong PW. Randomised trials of secondary prevention programmes in coronary heart disease: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:957–962. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7319.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell NC, Thain J, Deans HG, Ritchie LD, Rawles JM, Squair JL. Secondary prevention clinics for coronary heart disease: randomised trial of effect on health. BMJ. 1998;316:1434–1437. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7142.1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Thain J, Deans HG, Rawles JM, Squair JL. Secondary prevention in coronary heart disease: a randomised trial of nurse-led clinics in primary care. Heart. 1998;80:447–452. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.5.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roe L, Strong C, Whiteside C, Neil A, Mant D. Dietary intervention in primary care: validity of the DINE method for diet assessment. Fam Pract. 1994;11:375–381. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman LF, Breslow L. Health and ways of living. The Alameda County Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sever P, Beevers G, Bulpitt C, Lever A, Ramsay L, Reid J, et al. Management guidelines in essential hypertension: report of the second working party of the British Hypertension Society. BMJ. 1993;306:983–987. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6883.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bain NSC, Foster K, Grimshaw J, MacLeod TN, Broom J, Reid J, et al. Can audit of a local protocol for the management of lipid disorders effect and detect a change in clinical practice? Health Bull. 1997;55:94–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mills JK. Nurse run clinics in primary care increased secondary prevention in coronary heart disease. ACP Journal Club May-Jun, 1999.

- 13.Woodend AK. Nurse led secondary prevention clinics improved health and decreased hospital admissions in patients with coronary heart disease. Evidence Based Nurs. 1999;2:21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Weijden T, Grol R. Preventing recurrent coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1998;316:1400–1401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7142.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolly K, Bradley F, Sharp S, Smith H, Thompson S, Kinmonth A-L, et al. Randomised controlled trial of follow up care in general practice of patients with myocardial infarction and angina: final results of the Southampton heart integrated care project (SHIP) BMJ. 1999;318:706–711. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7185.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher M, Yudkin P, Wright L, Turner R, Fuller A, Schofield T, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial to compare three methods of promoting secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in primary care. BMJ. 2001;322:1338–1342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cupples ME, McKnight A. Randomised controlled trial of health promotion in general practice for patients at high cardiovascular risk. BMJ. 1994;309:993–996. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6960.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cupples ME, McKnight A. Five year follow up of patients at high cardiovascular risk who took part in randomised controlled trial of health promotion. BMJ. 1999;319:687–688. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell NC. Nurse led clinics for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a randomised trial in primary care. MD Thesis, University of Cambridge. 2001. [Google Scholar]