Abstract

Background

The incidence of pancreatic tuberculosis is extremely rare, and it frequently misdiagnosed as pancreatic neoplasms. The nonsurgical diagnosis of this entity continues to be a challenge.

Case presentation

A 33 year old male with six-month history of intermittent right epigastric vague pain and weight lost had found a solitary pancreatic cystic mass and diagnosed as pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma. The chest X-ray film and physical examination revealed no abnormalities. Abdominal ultrasound (US) examination showed an irregular hypoechoic lesion of 6.6 cm × 4.4 cm in the head of pancreas, and color Doppler flow imaging did not demonstrate blood stream in the mass. The attempts to obtain pathological evidence of the lesion by US-guided percutaneous fine needle aspiration failed, an exploratory laparotomy and incisional biopsy revealed a caseous abscess of the head of pancreas without typical changes of tuberculous granuloma, but acid-fast stain was positive.

Conclusions

Pancreatic tuberculosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of focal pancreatic lesions, especially for young people in developing countries.

Background

Tuberculosis is common in developing countries, but tuberculosis affecting intraabdominal organs is relatively uncommon. Abdominal tuberculosis mainly involves abdominal lymph nodes and the ileocecal junction, other organs that are uncommonly involved included the rest of gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, liver, and spleen [1,2]. Pancreatic involvement is extremely rare. Because of difficulty of obtaining the pathological evidence and rare awareness of tuberculosis, it is very difficult to confirm the diagnosis, always misled by pancreatic neoplasms. Therefore, pancreatic tuberculosis should be kept in mind among the differential diagnosis of solitary masses in the pancreas, especially in young people in developing countries. A patient with pancreatic head tuberculosis mimicking pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma is reported, which was diagnosed by exploratory laparotomy to be a tuberculous abscess. The patient responded to antituberculous drugs after drainage of the abscess.

Case presentation

A 33 year old male was admitted to our hospital presenting with six-month history of intermittent right epigastric vague pain, and having lost 5 kg in weight over a 2-month period. According to the patient's history, he had had no coughing, fever, jaundice, diarrhea, hematemesis and melena. He had never received a BCG vaccine, but there was no prior history of tuberculosis, or any family history. One month ago, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) performed at another affiliated hospital of our University showed a pancreatic cystic mass, and diagnosed as pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma. On admission, the physical examination revealed no abnormalities.

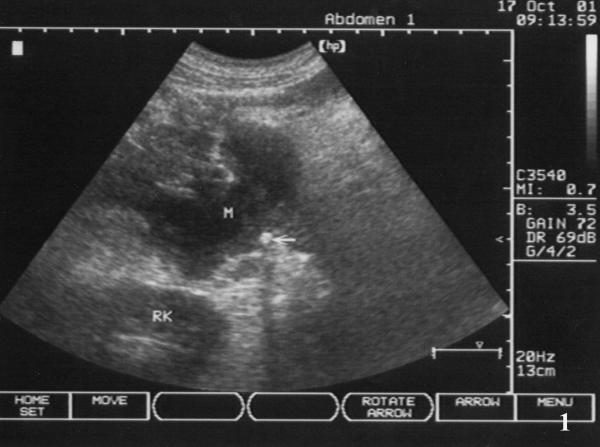

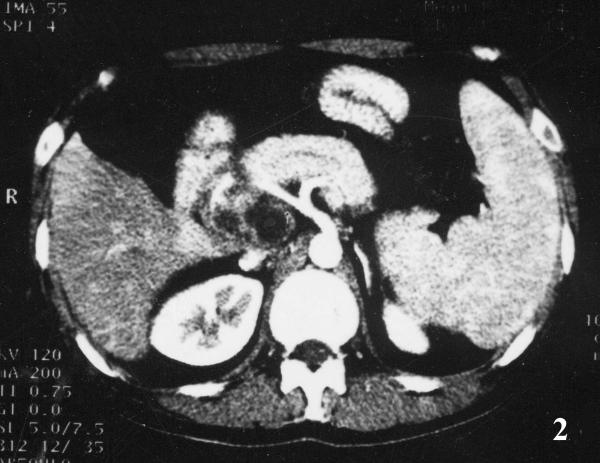

Initial laboratory values revealed a WBC count of 7.54 × 109/L (85.4% neutrophils, 9% lymphocytes, and 4.9% monocytes), Hb 8.7 g/L, ALT 96 U/L (normal 5–45 U/L), AST 161 U/L (normal 5–45 U/L), GGT 705 U/L (normal 4–50 U/L), and ALP 593 U/L (normal 42–128 U/L), Albumin 37.6 g/L and Globulin 34 g/L, Bilirubin, serum CEA, and amylase in serum and urine were all within normal limits; oral glucose tolerance test was normal, the detection of HBV, HCV and HIV were all negative. A chest X-ray film and hypotonic duodenography showed normal. Abdominal ultrasound (US) examination revealed an irregular hypoechoic lesion of 6.6 cm × 4.4 cm in the head of pancreas, and with a calcification at the edge of the mass, and without dilation of bile duct system and pancreatic duct (Fig 1); color Doppler flow imaging did not demonstrate blood stream in the mass. The above-mentioned contrast enhanced CT scan showed a inhomogeneous cystic mass in the head and uncinate process of the pancreas with peripheral rim enhancement, the body and tail of pancreas were normal; the head of pancreas, spleen were enlarged, and mild dilation of main pancreatic duct was also demonstrated (Fig 2). It was clinically suspected as pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma. Two attempts of US-guided percutaneous fine needle aspiration (FNA) failed due to tough tissue not permitting the needle to penetrate.

Figure 1.

Pancreatic lesion of ultrasonic finding. Abdominal ultrasound revealed an irregular contoured hypoechogenic lesion of 6.6 cm × 4.4 cm in the head of pancreas (M), with a calcification at the edge of the mass (fine arrow).

Figure 2.

Enhanced CT imaging of pancreas. Contrast enhanced CT scan showed an inhomogeneous cystic mass with peripheral rim enhancement, involving the head and uncinate process of the pancreas; enlarged spleen and mild dilation of main pancreatic duct were also demonstrated.

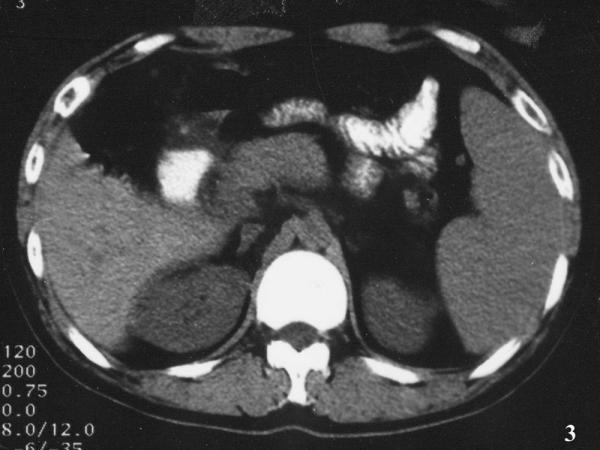

An exploratory laparotomy revealed 300 ml yellow ascite in abdominal cavity, lymphadenopathies around the hepatoduodenal ligament, and a few miliary nodules on pevic visceral peritoneum; omentum, liver and gall bladder were normal, serosal layer of the porta hepatis and the enlarged head of pancreas were edema without nodules. The head of pancreas was elastic hard to palpate. Incisional biopsy of the mass yielded a caseous material, and the wall of abscess cavity was about 1.2 cm in thickness. The cavity, mainly locating at pancreatic head, uncus and peri-pancreas, was separated by fibrotic septa and approximately contained 60 ml milk-like pus. The abscess wall revealed diffuse adipocyte vacuoles together with fibrocytes and lymphocytes suggestive of chronic inflammation on frozen section, but acid-fast stain was positive. After lavaging cavity, applying streptomycin 2.0 g in it, and placing a peripancreatic pigtail drainage, the laparotomy ended. Postoperative recovery was uneventful. Histopathology still confirmed chronic inflammation, without typical changes of tuberculous granuloma such as Langhan's giant cells or epithelioid histiocytes. Patient was started on 3-drug antitubercular regime and at follow up thereafter, patient was asymptomatic. The pancreas demonstrated normal in the CT scan after 7-month duration of antituberculous therapy, but the size of enlarged spleen remained invariable (Fig. 3). One year later, further examinations were performed for the patient to learn whether he has the potential risk of variceal bleeding. Moderate stenosis, not occlusion of splenic vein was confirmed by Doppler ultrasound; no esophageal or fundus varices was also found by gastroscopy.

Figure 3.

Abdominal CT imaging at 7-month follow-up. Pancreas was normal in the CT scan at 7-month duration of antituberculous therapy, but the enlarged spleen remained.

Discussion

Tuberculosis remains a major health problem in developing countries. In recent years developed countries too have seen a resurgence of this disease due to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and other immunodeficient states. The development of abdominal tuberculosis is independent of pulmonary disease in most patients, with the reported incidence of coexisting disease varying from 5% to 38% [1], and abdominal tuberculosis affected the pancreas is rarely. Auerbach reported in 1944 that 4.7% of 297 autopsy cases of military tuberculosis involved the pancreas [3]. Paraf et al in 1966 reviewed autopsy studies of military tuberculosis between 1891 and 1961 and found only an incidence of 2.1% (11/526) of pancreatic or peripancreatic involving [4]. In 1977, Bhansali did not report a single case involvement of the pancreas in 300 patients with abdominal tuberculosis from India [2].

The pathogenesis of pancreatic tuberculosis is inconclusive because most cases are in the absence of any detectable lesions in the other parts of the body. It is speculated that the tubercle bacilli reach the pancreas through hematogenous dissemination from an occult lesion in the lungs or abdomen. Actually, the route by direct spread from contiguous lymph nodes may be responsible for most of the cases with isolated pancreatic tuberculosis. That the pancreas is offended directly and destroyed subsequently by peripancreatic or periportal tubercular lymphadenopathy / ymphadenitis is a more convincible explanation for this condition, because the findings from CT [5,6] or the exploratory laparotomy [7] rarely demonstrate presenting absolute isolated pancreatic tuberculosis without adenopathies or other abdominal tubercular lesions, such as the present one. The pathological changes of adenopathy range from inflammatory exudates to caseous necrosis and abscess. The third possible way is that dormant bacilli in an old tubercular lesion can reactivate in an immunosuppressive state [6-8]. Stock et al in 1981 conceived of the toxic allergic reaction to generalized tuberculosis as a theoretical mechanism [9].

In our patient, he only presented with abdominal pain, weight loss, and minor ascites detected on laparotomy. Pancreatic tuberculosis could present with protean clinical manifestations, including upper abdominal pain, pyrexia of unknown origin, ascites, abdominal mass, obstructive jaundice, acute or chronic pancreatitis, upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to splenic vein thrombosis, diarrhea and weight loss. The nonspecific clinical and laboratory investigations combination with pancreatic masses on CT scan frequently lead to an erroneous primary diagnosis of a carcinoma [7], cystadenocarcinoma [6] or pseudocyst [10].

Abdominal CT and US may show an enlarged pancreas with focal hypodense or hypoechoic lesion, usually in the head region, sometimes with irregular multilobular cyst arising from pancreas, which was also seen in our patient. However, these findings are nonspecific and simulate solid and/or cystic pancreatic neoplasms [5,6]. In fact, there are no cardinal differences between radiologic appearances of cystic neoplasm and tuberculous abscess of pancreas, both of them have septa within mass, cyst with internal echos, and nearby hypodense lymphadenopathy. Calcified rim of cyst wall [11] and mural nodulars [12] are suggestive of characteristic findings for cystic neoplasms, but these occasionally present. A diagnosis of tuberculosis that can be suggested only in the presence of ancillary findings like pulmonary tuberculosis, pleural effusion, enlarged celiac lymph nodes, lesions in other solid viscera, ascites, mural thickening in the ileocecal region [1,5,6,13], or positive tuberculin test. The diagnosis of pancreatic tuberculosis can't be established without pathological confirmation by biopsy from FNA or exploration. US or CT-guided percutaneous FNA of tumor to obtain proof of the bacilli by the Ziehl-Neelsen stain or by culture is one diagnostic option, however, the aspiration of material from peripancreatic tumors or lymph nodes may be difficult, even if acid-fast stain for exact sampling, it showed to be positive only in 33~41% of cases of abdominal tuberculosis [14,15]. Furthermore, the potential risk of tumor dissemination sometimes prevents the physicians to perform FNA. Concerning the cases of cystic neoplasm, however, Lo et al [15] concluded that the spillage of tumor cells by FNA has not been reported, and FNA should be considered in young patients presenting with a cystic pancreatic mass. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of ascites was reported sometimes useful for those the bacterial cultures were negative [16]. Another diagnostic option involves initiating treatment with antituberculous drugs and evaluating the response of a tumor to this treatment. Nevertheless, the nonsurgical diagnosis of this entity continues to be a challenge, and laparotomy should be indicated to establish a diagnosis in most of the suspected cases. Other indications for an exploration are secondary complications, such as compression of common bile duct, or presenting gastrointestinal bleed.

In conclusion, a peripancreatic /pancreatic head cold abscess can mimic pancreatic cyst-adenoacarcinma. The clinican's high index of suspicion of tuberculosis and application of FNA to obtain pathological evidence are extremely important to a correct preoperative diagnosis. Provided diagnosis is established, anti-tuberculous chemotherapy or together with aspiration or pigtail drainage may be sufficient [10]. Surgery should be reserved either to establish diagnosis or to deal with associated complications.

List of abbreviations

ALP: alkaline phosphatase

ALT: alanine aminotransferase

AST: aspartate aminotransferase

CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen

CT: computed tomography

GGT: gamma glutamyl transferase

FNA: fine-needle aspiration

PCR: polymerase chain reaction

US: ultrasound

WBC: white blood cell

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

Three authors all participated the diagnosis and treatment. Quanda Liu was the first-line surgeon in ward and closely involved in the patients management. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

We thank the patient for giving us written consent for publishing his details.

Contributor Information

Quanda Liu, Email: liuquanda@sina.com.

Zhenping He, Email: hezp2000@yahoo.com.cn.

Ping Bie, Email: bieping@yahoo.com.cn.

References

- Hulnick DH, Megibow AJ, Naidich DP, Hilton S, Cho KC, Balthazar EJ. Abdominal tuberculosis: CT evaluation. Radiology. 1985;157:199–204. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.1.4034967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhansali SK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Experience with 300 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1977;67:324–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach O. Acute generalized military tuberculosis. Am J Pathol. 1944;20:121–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraf A, Menager C, Texier J. La tuberculose du pancreas et la tuberculose des ganglions de L'etage superior de L'abdomen. Rev Med-Chir Mal Foie. 1966;41:101–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pombo F, Diaz Candamio MJ, Rodriguez E, Pombo S. Pancreatic tuberculosis: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:394–397. doi: 10.1007/s002619900367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takhtani D, Gupta S, Suman K, Kakkar N, Challa S, Wig JD, Suri S. Radiology of pancreatic tuberculosis: a report of three cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1832–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memir K, Kaymakoglu S, Besisik F, Durakoglu Z, Ozdil S, Kaplan Y, Boztas G, Cakaloglu Y, Okten A. Solitary pancreatic tuberculosis in immunocompetent patients mimicking pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1071–1074. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizondo ME, Arratíbel JAA, Compton CC, Warshaw AL. Images in Surgery. Tuberculosis of the pancreas. Surgery. 2001;129:114–116. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.104364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock KP, Riemann JF, Stadler W, Rosch W. Tuberculosis of the pancreas. Endoscopy. 1981;13:178–180. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karia K, Mathur SK. Tuberculous cold abscess simulating pancreatic pseudocyst. J Postgrad Med. 2000;46:33–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornman PC, Beckingham IJ. ABC of diseases of liver, pancreas, and biliary system: Pancreatic tumours. BMJ. 2001;322:721–723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin I, Hammond P, Scott J, Redhead D, Carter DC, Garden OJ. Cystic tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1484–1486. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhan O, Pringot J. Imaging of abdominal tuberculosis. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:312–23. doi: 10.1007/s003300100994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kqduri VG, Janardhanan R, Hagan P, Brodmerkel GJ. Pancreatic TB: diagnosis by needle aspiration. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1206–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo SF, Ahchong AK, Tang CN, Yip AWC. Pancreatic tuberculosis: case reports and review of the literature. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Koyama H, Noie T, Shibayama K, Kitamura N. Abdominal tuberculoma mimicking a pancreatic neoplasm: report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25:365–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00311262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]