Abstract

Caenorhabditis elegans mitochondria have two elongation factor (EF)-Tu species, denoted EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2. Recombinant nematode EF-Ts purified from Escherichia coli bound both of these molecules and also stimulated the translational activity of EF-Tu, indicating that the nematode EF-Ts homolog is a functional EF-Ts protein of mitochondria. Complexes formed by the interaction of nematode EF-Ts with EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2 could be detected by native gel electrophoresis and purified by gel filtration. Although the nematode mitochondrial (mt) EF-Tu molecules are extremely unstable and easily form aggregates, native gel electrophoresis and gel filtration analysis revealed that EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes are significantly more soluble. This indicates that nematode EF-Ts can be used to stabilize homologous EF-Tu molecules for experimental purposes. The EF-Ts bound to two eubacterial EF-Tu species (E.coli and Thermus thermophilus). Although the EF-Ts did not bind to bovine mt EF-Tu, it could bind to a chimeric nematode–bovine EF-Tu molecule containing domains 1 and 2 from bovine mt EF-Tu. Thus, the nematode EF-Ts appears to have a broad specificity for EF-Tu molecules from different species.

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria from the nematode are known to have an unusual translation system that employs two types of extremely truncated tRNAs (1–4), namely the T arm-lacking (5) and the D arm-lacking tRNAs (6), and their corresponding elongation factor (EF)-Tu species that have been denoted EF-Tu1 (7) and EF-Tu2 (8), respectively. These EF-Tu molecules have been characterized and it is known that EF-Tu1 has a C-terminal extension of about 57 amino acids (7) not found in any other known EF-Tu. In addition, EF-Tu2 has a unique specificity for the aminoacyl moiety of seryl-tRNA (8). In contrast, little is known about nematode mitochondrial (mt) EF-Ts, a factor that facilitates the catalytic use of EF-Tu by promoting the exchange of GDP for GTP on EF-Tu (9). At present, only the cDNA sequence of the EF-Ts homolog in Caenorhabditis elegans has been reported (10). This cDNA sequence reveals that the nematode mt EF-Ts protein bears a putative mitochondria-specific transit peptide sequence at its N-terminus (10). On the basis of amino acid sequence homology, the nematode mt EF-Ts protein appears to fall into the long EF-Ts category, which includes EF-Ts molecules from mammalian mitochondria and eubacteria (excluding Thermus and cyanobacteria), rather than into the short EF-Ts category, which includes EF-Ts proteins from Thermus, cyanobacteria and plastids (10). These observations indicate that we can expect the nematode EF-Ts homolog to act like the well-characterized bovine mt EF-Ts (11–16) or Escherichia coli EF-Ts (17,18) molecule. This is particularly the case with respect to the former, since the nematode mt EF-Ts amino acid sequence shares more homology with bovine mt EF-Ts than with the E.coli EF-Ts.

The interaction between EF-Tu and EF-Ts was analyzed in detail by X-ray analysis of the crystal structure of EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes of E.coli (17) and Thermus thermophilus (19). Nematode EF-Ts is more homologous to E.coli EF-Ts than to T.thermophilus EF-Ts. However, C.elegans EF-Ts has only 24% amino acid identity with that of E.coli (10). As for the amino acid residues of E.coli EF-Ts that have been shown to interact with E.coli EF-Tu (17), only a few positions, such as Arg12, Asp80, Phe81, Gly126 and His149 (E.coli numbering) are conserved in nematode EF-Ts (10). Most of these residues occur in the N-terminal half of EF-Ts. Residues in the C-terminal half of E.coli EF-Ts that interact with EF-Tu domain 3 (17) are poorly conserved in C.elegans EF-Ts. Thus, as in the interaction between EF-Ts and EF-Tu of E.coli, the N-terminal half of C.elegans EF-Ts may interact with domain 1 of EF-Tu, whereas the interaction involving domain 3 may be quite different in C.elegans EF-Ts.

The activity and binding specificity for EF-Tu of bovine mt EF-Ts has been well characterized (12,13,16,20). Bovine mt EF-Ts forms an extremely tight complex with bovine mt EF-Tu (16,20). Furthermore, when bovine mt EF-Ts was expressed in E.coli, it was found to form a stable complex with E.coli EF-Tu (12,13). In contrast, E.coli EF-Ts does not seem to be able to bind bovine mt EF-Tu since a recombinant bovine mt EF-Tu expressed in E.coli could be purified as a free protein separate from E.coli EF-Ts (21). Work with E.coli–bovine EF-Ts chimeras also revealed that the N-terminal half of bovine mt EF-Ts, which includes the N-terminal domain and the subdomain N in the core domain, is important for its tight binding to EF-Tu (14).

The activity and EF-Tu binding specificity of the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog has not been previously investigated. In this work, we confirmed that this molecule is a proper EF-Ts as it is able to stimulate the guanine nucleotide exchange and the translational activity of EF-Tu and bind to both of the C.elegans mt EF-Tu proteins. We were able to purify complexes formed between C.elegans mt EF-Tu and EF-Ts, and found that these complexes are much more soluble than that of C.elegans EF-Tu alone. This suggests that C.elegans mt EF-Ts could be used as a tool to stabilize EF-Tu. Studies of the binding of C.elegans mt EF-Ts to various EF-Tu molecules revealed the broad specificity range of the EF-Ts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Buffers

Buffer A contained 50 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Buffer C contained 50 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 1 M NH4Cl, 10 mM imidazole, 1% glycerol and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. HiQ-A buffer consisted of 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.7), 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 1% glycerol and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). HiQ-B buffer is similar to the HiQ-A buffer except that the concentration of KCl is 500 mM. Tu·Ts buffer contained 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 3% glycerol and 1 mM DTT. PD buffer contained 50 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.6), 150 mM KCl, 10% glycerol and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Construction of a plasmid for the expression of the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog bearing a C-terminal His tag

The plasmid pET-yk141g2 contains the cDNA sequence of the predicted mature C.elegans EF-Ts homolog, i.e. it encodes a protein comprised of amino acids Ala21–Glu316 from its precursor sequence (10). It was constructed by placing the cDNA between the NcoI and XhoI sites of pET-15b (Novagen) and was kindly provided by Dr Y. Watanabe, who prepared it from the cDNA clone yg141g2 originally provided by Dr Y. Kohara (National Institute of Genetics, Japan). pET-yk141g2 was used to construct an expression vector encoding the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog bearing a C-terminal His tag. To add the six residue histidine tag to the EF-Ts C-terminus, the 17 bp sequence at the end of the EF-Ts coding sequence in pET-yk141g2 (5′-TAATTAGATAAAAGTGG-3′ in the coding strand, which is followed by the stop codon TAG) was replaced by the 18 bp sequence 5′-CACCATCATCAT CATCAT-3′ (in the coding strand) using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the supplier’s manual.

Expression and purification of the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog

The E.coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS (22) was transformed by the expression vector encoding the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog and grown and harvested as described (7). All purification procedures as described below were performed at 4°C. Cellular pellets (∼30 g) were resuspended with 30 ml of buffer A and lysed by sonication. The paste was then centrifuged for 1 h at 45 000 r.p.m. with a 70Ti rotor (Beckman) and the supernatant was collected and applied to a HiTrap chelating column (5 ml) (Amersham Biosciences) previously charged with Ni2+ ions and equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 30 ml of buffer C and then with 30 ml of buffer A containing 25 mM imidazole. Elution was performed using an imidazole gradient ranging from 25 to 150 mM in buffer A applied at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The fraction that included the EF-Ts was dialyzed against 500 ml of HiQ-A buffer for 4 h with two buffer changes. The dialyzed fraction (15 ml) was loaded onto an Econo-Pac High Q Cartridge (1 ml) (Bio-Rad) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min and the column was then rinsed with 5 ml of HiQ-A buffer at an equivalent flow rate. The flow-through, which now contained pure EF-Ts, was collected. The protein concentration was estimated by the dye-binding assay employed by the Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as the standard.

Preparation of EF-Tu variants

Recombinant proteins of C.elegans mt EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2, bovine mt EF-Tu, T.thermophilus EF-Tu and the two chimeric nematode–bovine EF-Tu variants BmCe3′ and BmCe3 were expressed in E.coli and purified on a Ni2+–NTA agarose column (Qiagen) as described (7,8). Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Tu1 bearing a C-terminal His tag was prepared using an expression vector containing N-terminal His-tagged cDNA encoding the predicted mature sequence of EF-Tu1 (a protein comprised of the Gly39–Pro496 sequence of its precursor protein) (7). This vector was amplified by PCR and inserted between the SphI and BglII sites of pQE-70 (Qiagen), which was then used to transform E.coli strain BL21. The recombinant protein bearing the additional amino acid sequence RSHHHHH at its C-terminus was then expressed and purified as described (7). Escherichia coli EF-Tu was purified from its native source as described (23). The protein concentration of each EF-Tu was estimated using the Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad) with BSA as the standard.

Measurement of guanine nucleotide exchange with EF-Tu

The assay was performed basically according to Schwartzbach and Spremulli (20). Briefly, 80 pmol EF-Tu and various amounts of EF-Ts were incubated for 10 min at 37°C in a final volume of 50 µl reaction mixture containing 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 50 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 50 µM [3H]GDP, then the [3H]GDP bound to EF-Tu in each sample was counted as described (20).

In vitro translation

Bovine mt translation factors, namely ribosomes (prepared as described; 24), EF-G [partially purified according to Chung and Spremulli (25)] and tRNAPhe were kindly provided by Dr C. Takemoto. Poly(U)-dependent poly(Phe) synthesis was performed in vitro using these translation factors as described (25) except that 9 pmol [14C]Phe-tRNA of bovine mitochondria was used in each 20 µl reaction mixture and the concentrations of EF-Tu and EF-Ts were 0.8 and 0.5 µM, respectively. The radioactivity retained on the filter in the absence of EF-Tu and EF-Ts (blank) was subtracted from the radioactivity obtained in the presence of EF-Tu (and EF-Ts) in each assay.

Native gel electrophoresis

Native gel electrophoresis of EF-Tu and EF-Ts was performed at 4°C (450 V, 2 h) on a 1 mm × 10 cm × 10 cm 9% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide:bisacrylamide 29:1) containing 8 mM Tricine–NaOH (pH 8.2), 1 mM EDTA and 5% glycerol. The buffer used contained 8 mM Tricine–NaOH (pH 8.2) and 1 mM EDTA. To analyze the interaction between EF-Tu and EF-Ts, recombinant EF-Tu and EF-Ts were mixed on ice in a reaction mixture of 6.5 µl that included 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 70 mM KCl, 1.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 38 pmol EF-Ts and either 12.5 or 25 pmol EF-Tu. Each reaction was then loaded on the gel, electrophoresed, and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (NACALAI Tesque Inc.).

EF-Ts pull-down assay

His-tagged C.elegans mt EF-Ts (2 µg/tube) in the absence or presence of E.coli, T.thermophilus or bovine mt EF-Tu (4 µg/tube) were incubated at 4°C for 10 min in 50 µl of PD buffer. The mixture was centrifuged at 17 000 g for 7 min. The supernatant was mixed with Ni2+–NTA magnetic agarose beads (Qiagen) (20 µl of 5% bead slurry suspended in PD buffer) and incubated at 4°C for 15 min with weak agitation. The beads were collected using a magnet and washed twice with 400 µl of PD buffer containing 10 mM imidazole, then eluted twice with 30 µl of buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 400 mM imidazole and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The eluents were desalted on a Centri-Sep spin column (Applied Biosystems) and concentrated to 5 µl. The samples were analyzed by SDS–PAGE.

Analysis and purification of the C.elegans mt EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes by gel filtration

Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Tu purified on a Ni2+-NTA column (7,8) and the EF-Ts purified as described above were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:1.5. The mixture was dialyzed against Tu·Ts buffer for 15 h with two buffer changes. The sample was concentrated to less than 1 ml using an Ultrafree-15 centrifugal filter device (Millipore) and the insoluble fraction was removed by centrifugation. The sample was loaded on a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 column (Amersham Biosciences) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min and eluted with Tu·Ts buffer. Each of the gel filtrated fractions was analyzed by SDS–PAGE.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog

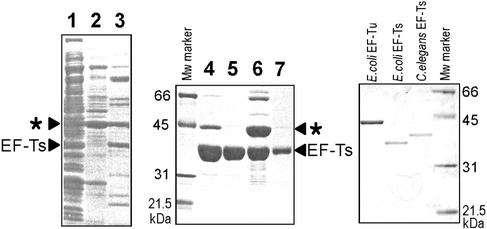

Although the recombinant C.elegans EF-Ts homolog expressed in E.coli cells was almost separated from E.coli proteins by use of the Ni2+-HiTrap chelating column (Fig. 1, lanes 4 and 7) and repeated column washes (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 3), the preparation still contained some impurities. One protein, shown by an asterisk in Figure 1, which apparently associates with the EF-Ts homolog, was particularly difficult to remove. The size of this protein suggested that it could be E.coli EF-Tu (∼43.2 kDa). This EF-Tu-like protein could eventually be removed by passing the 15 ml Ni2+-HiTrap preparation containing 72 mg protein (Fig. 1, lane 4) through a HighQ column. After running through 5 ml of HiQ-A buffer, most of the loaded EF-Ts was recovered (∼60 mg) (Fig. 1, lane 5) in pure form. After that, the column was washed with 5 ml of HiQ-B buffer; the fraction eluted with the buffer contained the impurities as well as the EF-Ts (∼11 mg) (Fig. 1, lane 6). Pure materials (lane 5) were used in all assays (Figs 2–6).

Figure 1.

SDS–PAGE analysis of the recombinant C.elegans EF-Ts preparations at various purification steps using Ni2+ column and HighQ column chromatography. Lane 1, the flow-through after loading the sample onto a Ni2+ column; lane 2, the first wash with buffer C; lane 3, the second wash with buffer A that included 25 mM imidazole; lanes 4 and 7, the Ni2+ column fraction that included the EF-Ts homolog [To detect possible impurities, lane 4 was overloaded with the sample. To show that there is no second protein co-migrating with C.elegans EF-Ts, such as E.coli EF-Ts, a smaller volume of sample (one-eighth of the amount loaded onto lane 4) was loaded in lane 7]; lane 5, the flow-through after loading the sample from the Ni2+ column onto the HighQ column; lane 6, the wash with HiQ-B buffer. The SDS–PAGE standard (Bio-Rad), purified E.coli EF-Tu and recombinant E.coli EF-Ts were used as protein size markers.

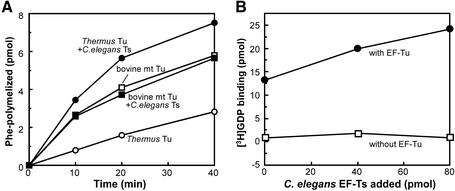

Figure 2.

Stimulation of the activity of EF-Tu by the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog. (A) In vitro poly(U)-dependent poly(Phe) synthesis (25) was performed using bovine mt ribosome (2.0 A260 units/ml, 125 U/ml, 63.4 nM), EF-G [2500 U/ml (saturated amount); unit definition as in Chung and Spremulli (25)] and bovine mt Phe-tRNAPhe in the presence of T.thermophilus EF-Tu alone (open circle), T.thermophilus EF-Tu plus C.elegans EF-Ts homolog (filled circle), bovine mt EF-Tu alone (open square) or bovine mt EF-Tu plus C.elegans EF-Ts homolog (filled square). Aliquots of the reaction mixture (18 µl) were withdrawn at appropriate times and the radioactivity of the hot TCA-insoluble material was measured. (B) Stimulation of GDP exchange activity of EF-Tu by C.elegans EF-Ts. The EF-Ts stimulates the GDP exchange of T.thermophilus EF-Tu (filled circle). [3H]GDP binding to EF-Ts was not detected in the absence of EF-Tu (open square).

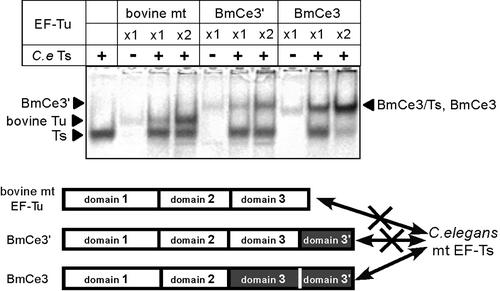

Figure 6.

Native PAGE analysis of the ability of C.elegans mt EF-Ts to bind to bovine mt EF-Tu (bovine mt) and chimeric nematode–bovine EF-Tu variants (BmCe3′ and BmCe3). The lower part of the figure indicates a summary of the binding specificity of C.elegans mt EF-Ts to the EF-Tu variants. White boxes with black letters show the bovine mt domains and gray filled boxes with white letters show the nematode mt domains. Domain 3′ represents the C-terminal 57 amino acid extension that is specific for C.elegans mt EF-Tu1.

Nematode mt EF-Ts can stimulate guanine nucleotide exchange and in vitro translation

To verify that the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog is indeed an EF-Ts, we first examined its ability to stimulate poly(U)-dependent poly(Phe) synthesis mediated by EF-Tu molecules. A bovine mt in vitro translation system was used because a homologous nematode mt translation system is as yet unavail able. The EF-Ts homolog stimulated poly(U)-dependent poly(Phe) synthesis activity of T.thermophilus EF-Tu but not bovine mt EF-Tu (Fig. 2A). The poly(Phe) synthesis activity of bovine mt EF-Tu can be activated by bovine mt EF-Ts (13). Poly(Phe) synthesis using mt EF-Tu does not appear to be maximal in this assay because the addition of increased amounts of bovine mt EF-Tu increased poly(Phe) synthesis (data not shown). Thus, the observation that the EF-Ts homolog did not change the activity of bovine mt EF-Tu cannot be explained by the presence of an already saturating amount of mt EF-Tu activity in this assay. As will be seen, this differential activity of the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog is consistent with its EF-Tu binding specificity, as it complexes with T.thermophilus EF-Tu but cannot bind bovine mt EF-Tu (see below). The observation that the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog stimulates the translational activity of T.thermophilus EF-Tu agrees with the results of filter binding assays of EF-Tu·GDP (Fig. 2B). The assays demonstrated that the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog stimulates the GDP exchange of T.thermophilus EF-Tu (Fig. 2B). Unfortunately, GDP exchange with bovine and nematode mt EF-Tu was hardly detectable, even with nematode mt EF-Ts (data not shown). This is reminiscent of previous failure to detect GDP exchange with bovine mt EF-Tu even with bovine mt EF-Ts by the same assay (20). All these observations strongly suggest that the C.elegans EF-Ts homolog is indeed a functional EF-Ts.

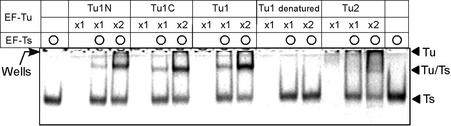

Binding of nematode mt EF-Ts to nematode mt EF-Tu proteins

To assess whether C.elegans EF-Ts can bind to either or both C.elegans mt EF-Tu molecules (EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2), the binding of recombinant C.elegans EF-Ts to recombinant Tu proteins was analyzed by native PAGE. In the absence of C.elegans EF-Ts, EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2 stayed in the wells of the gel (Fig. 3). In contrast, when C.elegans EF-Ts was present, complexes were formed and these migrated into the gel (Fig. 3). While the band of the EF-Tu2·EF-Ts complex in the native PAGE gel is rather diffuse, later experiments with gel filtration chromatography clearly revealed the presence of the complex (Fig. 4C), thus confirming the association. With regard to EF-Tu1, we assessed the ability of C.elegans EF-Ts to bind to EF-Tu1 bearing an N-terminal His tag (Tu1N), a C-terminal His tag (Tu1C) or no tag (Fig. 3). Heat-denatured EF-Tu1 was also tested. Caenorhabditis elegans EF-Ts bound to the EF-Tu1 molecules bearing N- or C-terminal His tags as well as to untagged EF-Tu1, which suggests that the N- and C-termini of EF-Tu1 are not important for its binding to C.elegans EF-Ts. Denatured EF-Tu1 did not bind to C.elegans EF-Ts, indicating that the native conformation of EF-Tu1 is necessary for its binding to C.elegans EF-Ts. Thus, C.elegans EF-Ts binds to both EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2 of C.elegans mitochondria, demonstrating that nematode EF-Ts could be a functional EF-Ts in C.elegans mitochondria.

Figure 3.

Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Ts can bind to nematode EF-Tu molecules. The ability of C.elegans mt EF-Ts to bind to C.elegans mt EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2 was analyzed by loading a mixture of 38 pmol EF-Ts and/or 12.5 (×1) or 25 pmol (×2) of EF-Tu onto a native gel. Several different forms of EF-Tu1 were assessed, namely EF-Tu1 with an N-terminal His tag (Tu1N), EF-Tu1 with a C-terminal His tag (Tu1C), EF-Tu1 lacking a His tag (Tu1) and heat-denatured EF-Tu1 (Tu1 denatured). Heat denaturation of EF-Tu1 was performed at 90°C for 5 min. The positions of the wells are indicated by an arrow on the left side of the gel.

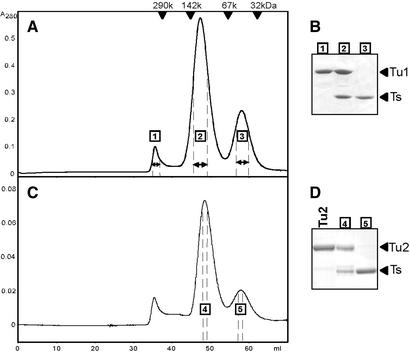

Figure 4.

Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes can be purified by HiPrep Sephacryl S-200 column chromatography. (A) Gel filtration of C.elegans mt EF-Tu1 and EF-Ts. Peak positions of molecular weight marker proteins (Oriental Yeast Co.) are indicated. (B) Each peak in (A) was analyzed by SDS–PAGE. Before loading, 100 µl of fraction 1 was concentrated to 5 µl and 3 µl aliquots of fractions 2 and 3 were loaded on the gel without concentrating the proteins. (C) Gel filtration of C.elegans mt EF-Tu2 and EF-Ts. (D) Each peak in (C) was analyzed by SDS–PAGE. Before loading, 10 µl of fraction 4 and 50 µl of fraction 5 were concentrated to 5 µl solutions and loaded on the gel. The lane indicated by Tu2 contains C.elegans mt EF-Tu2 without a His tag (2 µg).

Reconstitution and isolation of C.elegans mt EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes

The complexes formed between recombinant C.elegans mt EF-Ts and EF-Tu1 or EF-Tu2 could be efficiently separated from EF-Tu and EF-Ts proteins by gel filtration using a HiPrep Sephacryl S-200 column (Fig. 4A and C). The three peaks on the gel filtration chromatograms for EF-Tu1 (Fig. 4A) and EF-Tu2 (Fig. 4C) were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and the middle peak (denoted fractions 2 and 4) was found to comprise the EF-Tu·EF-Ts complex (Fig. 4B and D). Native PAGE analysis of fraction 2 in the gel filtration chromatogram for EF-Tu1 confirmed that it contained EF-Tu1·EF-Ts complexes (data not shown). EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2 were eluted faster than the EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes, which suggests that these molecules aggregate in the Tu·Ts buffer in the absence of EF-Ts (Fig. 4A and C). Similar patterns were observed for EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2 when gel filtration was performed using a Superdex 75 HR 10/30 (Amersham Biosciences) gel filtration column with the same buffer, although in this system the separation of EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes from EF-Ts was poor (data not shown).

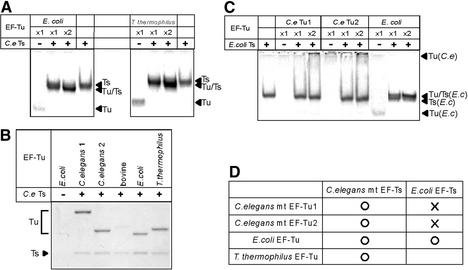

Ability of nematode mt EF-Ts to bind to different EF-Tu molecules

To characterize the binding specificity of C.elegans mt EF-Ts, its binding to heterologous EF-Tu proteins was analyzed. The addition of C.elegans EF-Ts to E.coli EF-Tu and T.thermophilus EF-Tu caused the EF-Tu bands to disappear and a new band containing the EF-Tu·EF-Ts complex to appear slightly below the EF-Ts band (Fig. 5A). This suggests that C.elegans mt EF-Ts can bind to both of these EF-Tu molecules. The complexes between bacterial EF-Tu molecules and C.elegans mt EF-Ts were further confirmed by pull-down assay (Fig. 5B). In contrast, E.coli EF-Ts did not appear to complex with either EF-Tu1 or EF-Tu2 from C.elegans (Fig. 5C). Thus, the binding specificity of C.elegans mt EF-Ts differs from that of E.coli EF-Ts (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Analysis of binding specificity of C.elegans mt EF-Ts to various EF-Tu molecules. (A) Native gel analysis of C.elegans mt EF-Ts mixed with EF-Tu from E.coli or T.thermophilus. (B) Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Ts was pulled down by using Ni–NTA magnetic agarose beads in the presence of C.elegans mt, bovine mt or bacterial EF-Tu. The fractions pulled down were analyzed by 10% SDS–PAGE. (C) Native gel analysis of E.coli EF-Ts mixed with C.elegans mt EF-Tu1 or EF-Tu2 or E.coli EF-Tu. (D) Summary of the binding specificities of nematode mt and bacterial EF-Tu molecules to nematode mt and bacterial EF-Ts proteins.

Although C.elegans mt EF-Ts could bind to bacterial EF-Tu, it could not bind to bovine mt EF-Tu (Fig. 6), which was confirmed by pull-down assay (Fig. 5B) and gel filtration analysis (data not shown). The ability of C.elegans EF-Ts to bind to two chimeric EF-Tu constructs composed of bovine mt and nematode mt EF-Tu domains was also analyzed (Fig. 6). BmCe3 contains domains 1 and 2 of bovine mt EF-Tu while BmCe3′ contains domain 1–3 of bovine mt EF-Tu. Both of these variants can bind to Met-tRNAMet from E.coli or C.elegans mitochondria (7). Although the BmCe3·EF-Ts band was not separated from the BmCe3 band on the native PAGE gel, the intensity of the C.elegans EF-Ts band was reduced when BmCe3 was added, indicating that C.elegans mt EF-Ts binds to BmCe3 (Fig. 6). In contrast, C.elegans mt EF-Ts did not bind to the BmCe3′ chimera (Fig. 6). These observations indicate that domains 1 and 2 of bovine mt EF-Tu do not prevent C.elegans mt EF-Ts binding, unlike domain 3 of bovine mt EF-Tu.

DISCUSSION

Structural features of C.elegans mt EF-Ts

EF-Ts molecules from E.coli and T.thermophilus have been well characterized. Crystals of these two molecules complexed with EF-Tu revealed that they interact with EF-Tu differently, as E.coli EF-Tu and EF-Ts form a heterodimer (Tu·Ts) (17,26) while the T.thermophilus factors form a dyad symmetric heterotetramer [Tu·(Ts)2·Tu] (19,26,27). The amino acid sequence of C.elegans mt EF-Ts resembles more closely that of E.coli EF-Ts than that of T.thermophilus EF-Ts. The peak retention volumes of C.elegans mt factors in the gel filtration chromatogram are also suggestive of the formation of a EF-Ts·EF-Tu heterodimer (83.5 kDa for EF-Tu1·EF-Ts and 77.8 kDa for EF-Tu2·EF-Ts) (Fig. 4A and C). The peak retention volume of C.elegans mt EF-Ts suggests the EF-Ts is a 32.8 kDa monomer.

Purification of the C.elegans mt EF-Tu·Ts complex

Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2 are particularly unstable, which makes handling them very difficult. For example, they are easily precipitated during dialysis against low salt solutions as well as by concentrations of EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2 that exceed ∼2 and ∼1 mg/ml, respectively. Furthermore, they aggregate under conditions of native gel analysis (Fig. 3) and gel filtration (Fig. 4). Such instability and low solubility complicates their use in experiments that require high protein concentrations or various solution conditions (e.g. crystallization for X-ray analysis). In contrast, the C.elegans mt EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes are highly soluble (>10 mg/ml) and appear to be more stable than the EF-Tu alone under a wide variety of conditions. Recently it was reported that E.coli EF-Ts could act as a structural chaperone to improve the solubility of unstable EF-Tu mutants (28). Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Ts could be similarly used to increase the solubility and stability of nematode EF-Tu molecules. Thus, the procedure we developed to purify nematode mt EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes may be a useful tool for the analysis of nematode mt EF-Tu molecules.

Specificity of C.elegans mt EF-Ts for different EF-Tu molecules

Bovine mt EF-Ts expressed in E.coli is known to form an extremely tight complex with E.coli EF-Tu in vivo (13). The complex cannot be dissociated completely even in the presence of 8 M urea or 8 M guanidine hydrochloride (13). In this work, a similar phenomenon was observed for C.elegans mt EF-Ts when it was expressed in E.coli. When we tried to purify the recombinant C.elegans mt EF-Ts protein on a Ni2+ column, we found it was difficult to remove a protein contaminant whose molecular weight agreed with that of E.coli EF-Tu. The binding between the two proteins was loose enough, however, to allow the EF-Tu-like protein to be largely eliminated by repeated column washes (Fig. 1, lanes 1–4). Native gel analysis confirmed that C.elegans mt EF-Ts and E.coli EF-Tu can form a heterologous complex (Fig. 5A). Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Ts also bound to T.thermophilus EF-Tu and to the two mt EF-Tu molecules from C.elegans itself, suggesting that it has broad specificity. Such broad specificity is probably required for it to be able to recognize the two distinct EF-Tu species in the C.elegans mitochondria. Notwithstanding this broad specificity, the EF-Ts was unexpectedly not able to bind to bovine mt EF-Tu (Fig. 6). The lack of binding of C.elegans mt EF-Ts to bovine mt EF-Tu was examined further by using chimeric nematode–bovine EF-Tu molecules. Caenorhabditis elegans mt EF-Ts was able to bind to a chimeric C.elegans mt EF-Tu that contained domains 1 and 2 of bovine mt EF-Tu but not to a chimera that contained domain 3 of bovine mt EF-Tu, indicating that domain 3 of bovine mt EF-Tu prevents the binding of EF-Ts but domains 1 and 2 do not.

A previous study has shown that strong binding of bovine mt EF-Ts to EF-Tu is due to its N-terminal half and that the N-terminal half of bovine mt EF-Ts enables it to bind heterologous EF-Tu (14). The crystal structure of the E.coli EF-Tu·EF-Ts complex shows that the N-terminal half of EF-Ts binds to domain 1 of EF-Tu (17). The amino acid identity between the N-terminal halves of C.elegans mt EF-Ts and bovine mt EF-Ts (40.0%) is much higher than that between C.elegans mt EF-Ts and bacterial EF-Ts. For example, the homology with E.coli EF-Ts was only 27.7%. Thus, it is likely that the N-terminal half of C.elegans mt EF-Ts also enables it to bind heterologous EF-Tu proteins like bacterial EF-Tu and the chimera bearing domains 1 and 2 from bovine mt EF-Tu. The fact that C.elegans mt EF-Ts cannot bind the EF-Tu chimera bearing bovine domain 3 can be explained as follows. The crystal structure of the E.coli EF-Tu·EF-Ts complex reveals that the C-terminal half of EF-Ts interacts with domain 3 of EF-Tu (17). The amino acid identity between the C-terminal halves of the C.elegans and bovine mt EF-Ts molecules is not very high (22.9%) and thus it is likely that the C-terminal half of C.elegans mt EF-Ts cannot support binding to domain 3 of bovine mt EF-Tu.

In conclusion, C.elegans mt EF-Ts recognizes a common structure shared by C.elegans mt EF-Tu1 and EF-Tu2, E.coli EF-Tu and T.thermophilus EF-Tu, as well as domains 1 and 2 from bovine mt EF-Tu. Further analysis using EF-Tu mutants or crystallographic analysis will elucidate the molecular mechanism by which EF-Tu is recognized by the EF-Ts.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Y. Watanabe (University of Tokyo, Japan) for materials and valuable discussions, Dr C. Takemoto for materials, Dr G. Andersen (Aarhus University, Denmark) for helpful suggestions about the procedure used to purify the EF-Tu·EF-Ts complexes and Mr Y. Shimizu (University of Tokyo) for his gift of recombinant E.coli EF-Ts. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan to K.W. and a Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists to T.O.

REFERENCES

- 1.Okimoto R., Macfarlane,J.L., Clary,D.O. and Wolstenholme,D.R. (1992) The mitochondrial genomes of two nematodes, Caenorhabditis elegans and Ascaris suum. Genetics, 130, 471–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe Y., Tsurui,H., Ueda,T., Furushima,R., Takamiya,S., Kita,K., Nishikawa,K. and Watanabe,K. (1994) Primary and higher order structures of nematode (Ascaris suum) mitochondrial tRNAs lacking either the T or D stem. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 22902–22906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe Y., Tsurui,H., Ueda,T., Furushima-Shimogawara,R., Takamiya,S., Kita,K., Nishikawa,K. and Watanabe,K. (1997) Primary sequence of mitochondrial tRNAArg of a nematode Ascaris suum: occurrence of unmodified adenosine at the first position of the anticodon. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1350, 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keddie E.M., Higazi,T. and Unnasch,T.R. (1998) The mitochondrial genome of Onchocerca volvulus: sequence, structure and phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 95, 111–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohtsuki T., Kawai,G. and Watanabe,K. (1998) Stable isotope-edited NMR analysis of Ascaris suum mitochondrial tRNAMet having a TV-replacement loop. J. Biochem., 124, 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohtsuki T., Kawai,G. and Watanabe,K. (2002) The minimal tRNA: unique structure of Ascaris suum mitochondrial tRNASerUCU having a short T arm and lacking the entire D arm. FEBS Lett., 514, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtsuki T., Watanabe,Y., Takemoto,C., Kawai,G., Ueda,T., Kita,K., Kojima,S., Kaziro,Y., Nyborg,J. and Watanabe,K. (2001) An “elongated” translation elongation factor Tu for truncated tRNAs in nematode mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 21571–21577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohtsuki T., Sato,A., Watanabe,Y. and Watanabe,K. (2002) A unique serine-specific elongation factor Tu found in nematode mitochondria Nature Struct. Biol., 9, 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller D.L. and Weissbach,H. (1970) Interactions between the elongation factors: the displacement of GDP from the Tu-GDP complex by factor Ts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 38, 1016–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe Y., Kita,K., Ueda,T. and Watanabe,K. (1997) cDNA sequence of a translational elongation factor Ts homologue from Caenorhabditis elegans: mitochondrial factor-specific features found in the nematode homologue peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1353, 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartzbach C.J., Farwell,M., Liao,H.X. and Spremulli,L.L. (1996) Bovine mitochondrial initiation and elongation factors. Methods Enzymol., 264, 248–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xin H., Woriax,V., Burkhart,W. and Spremulli,L.L. (1995) Cloning and expression of mitochondrial translational elongation factor Ts from bovine and human liver. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 17243–17249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xin H., Leanza,K. and Spremulli,L.L. (1997) Expression of bovine mitochondrial elongation factor Ts in Escherichia coli and characterization of the heterologous complex formed with prokaryotic elongation factor Tu. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1352, 102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., Sun,V. and Spremulli,L.L. (1997) Role of domains in Escherichia coli and mammalian mitochondrial elongation factor Ts in the interaction with elongation factor Tu. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 21956–21963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y. and Spremulli,L.L. (1998) Role of residues in mammalian mitochondrial elongation factor Ts in the interaction with mitochondrial and bacterial elongation factor Tu. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 28142–28148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Y., Bullard,J.M., Thompson,N.L. and Spremulli,L.L. (2000) Interaction of mitochondrial elongation factor Tu with aminoacyl-tRNA and elongation factor Ts. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 20308–20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawashima T., Berthet-Colominas,C., Wulff,M., Cusack,S. and Leberman,R. (1996) The structure of the Escherichia coli EF-Tu/EF-Ts complex at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature, 379, 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gromadski K.B., Wieden,H.J. and Rodnina,M.V. (2002) Kinetic mechanism of elongation factor Ts-catalyzed nucleotide exchange in elongation factor Tu. Biochemistry, 41, 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y., Jiang,Y., Meyering-Voss,M., Sprinzl,M. and Sigler,P.B. (1997) Crystal structure of the EF-Tu/EF-Ts complex from Thermus thermophilus. Nature Struct. Biol., 4, 650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartzbach C.J. and Spremulli,L.L. (1989) Bovine mitochondrial protein synthesis elongation factors. Identification and initial characterization of an elongation factor Tu-elongation factor Ts. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 19125–19131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woriax V.L., Burkhart,W. and Spremulli,L.L. (1995) Cloning, sequence analysis and expression of mammalian mitochondrial protein synthesis elongation factor Tu. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1264, 347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Studier F.W., Rosenberg,A.H., Dunn,J.J. and Dubendorff,J.W. (1990) Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol., 185, 60–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobson G.R. and Rosenbusch,J.P. (1977) Affinity purification of elongation factors Tu and Ts. FEBS Lett., 79, 8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eberly S.L., Locklear,V. and Spremulli,L.L. (1985) Bovine mitochondrial ribosomes. Elongation factor specificity. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 8721–8725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung J.K.H. and Spremulli,L.L. (1990) Purification and characterization of elongation factor G from bovine liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem., 265, 21000–21004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arai K., Arai,N., Nakamura,S., Oshima,T. and Kajiro,Y. (1978) Studies on polypeptide chain elongation factors from an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus HB8. Eur. J. Biochem., 92, 521–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nesper M., Nock,S., Sedlak,E., Antalik,M., Podhradsky,D. and Sprinzl,M. (1998) Dimers of Thermus thermophilus elongation factor Ts are required for its function as a nucleotide exchange factor of elongation factor Tu. Eur. J. Biochem., 255, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krab I.M., Biesebeke,R., Bernardi,A. and Parmeggiani,A. (2001) Elongation factor Ts can act as a steric chaperone by increasing the solubility of nucleotide binding-impaired elongation factor-Tu. Biochemistry, 40, 8531–8535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]