Abstract

The major structural features of the Escherichia coli MscS mechanosensitive channel protein have been explored using alkaline phosphatase (PhoA) fusions, precise deletions and site-directed mutations. PhoA protein fusion data, combined with the positive-inside rule, strongly support a model in which MscS crosses the membrane three times, adopting an Nout–Cin configuration. Deletion data suggest that the C-terminal domain of the protein is essential for the stability of the MscS channel, whereas the protein will tolerate small deletions at the N-terminus. Four mutants that exhibit either gain-of-function (GOF) or loss-of-function have been identified: a double mutation I48D/S49P inactivates MscS, whereas the MscS mutants T93R, A102P and L109S cause a strong GOF phenotype. The similarity of MscS to the last two domains of MscK (formerly KefA) is reinforced by the demonstration that expression of a truncated MscK protein can substitute for MscL and MscS in downshock survival assays. The data derived from studies of the organization, conservation and the influence of mutations provide significant insights into the structure of the MscS channel.

Keywords: alkaline phosphatase/gain of function/MscK/structure/topology

Introduction

Bacterial cells maintain an outwardly directed turgor pressure through the accumulation of solutes against their chemical gradient, leading to water flow into the cytoplasm (Epstein, 1986). The pressure appears to be essential for the growth of the bacterial cell via the maintenance of an expansive force that enables cell enlargement (O’Byrne and Booth, 2002). In high osmolarity environments, bacteria accumulate solutes to ensure the continued flow of water into the cytoplasm. When subjected to hypo-osmotic stress (rapid transfer from a high osmolarity environment to one of lower osmotic pressure; ‘downshock’), bacteria release solutes from the cytoplasm, thus preventing excessive water inflow (Berrier et al., 1992; Booth and Louis, 1999; Levina et al., 1999). The major proteins involved in rapid solute release are the mechanosensitive channels (MS channels) (Berrier et al., 1992; Blount et al., 1996a; Poolman et al., 2002).

In Escherichia coli, there are three recognized groups of MS channel activities, defined on the basis of their electrical conductance and their pressure threshold for activation: MscM, a small (mini) channel opened by low pressure; MscS, an ∼1 nS channel opened by moderate pressure; and MscL, which exhibits the largest conductance and only opens at very high membrane tension (Blount et al., 1999; Sukharev, 1999). MscL, encoded by the mscL gene (Sukharev et al., 1994), is a 136 amino acid protein organized into two transmembrane spans (TMS), separated by a long loop. The N- and C-termini reside in the cytoplasm (Blount et al., 1996b). Although deletion of a considerable part of these cytoplasmic sequences has been reported not to affect the activity of the channel, recent models suggest that these segments play crucial roles in the gating and structure of MscL (Sukharev et al., 2001a,b; A.Anishkin and S.Sukharev, personal communication). The MscL protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been crystallized in the closed state, and this structure is the basis of models of gating of the channel (Chang et al., 1998; Sukharev et al., 2001a,b). Key residues that form the hydrophobic lock of the closed channel have been identified (Blount et al., 1997; Moe et al., 1998; Ou et al., 1998), and the short, N-terminal S1 helix, which was missing from the crystal structure, is proposed to form a second gate (Sukharev et al., 2001a,b; but for an alternative view see Kong et al., 2002). Despite the elegance of this model, it seems unlikely that it can be transferred directly to other MS channels (e.g. MscS and MscK), which display more complex structures (Levina et al., 1999; Kloda and Martinac, 2001; McLaggan et al., 2002; Pivetti et al., 2003).

MscS activity of E.coli, detected by electrophysio logical analysis, is the sum of two channels KefA and YggB (Levina et al., 1999). The YggB protein has been reconstituted alone in lipid vesicles and shown to form functional channels with the same conductance as MscS (Okada et al., 2002; Sukharev, 2002). On this basis, it is proposed that YggB should be renamed MscS and that KefA, which has a similar conductance but has specific interactions with K+, be called MscK (Li et al., 2002). This terminology has been adopted throughout this manuscript. MscK and MscS proteins differ in their size, being 1120 and 286 residues, respectively, but the whole family is extremely variable in length and sequence such that ∼100 members of the family form >18 subfamilies (Pivetti et al., 2003). The family extends from archaea to plants and is thus more widespread than MscL (Pivetti et al., 2003). The MscK and MscS proteins only exhibit sequence and organizational similarity in the C-terminal ∼300 amino acids (Levina et al., 1999; Touze et al., 2001). Mutants lacking MscS and MscL do not survive extreme hypo-osmotic shock, but the further loss of MscK (i.e. MscL–MscS–MscK–) does not significantly worsen the survival in downshock assays (Levina et al., 1999). Thus, the MscS protein appears to be central to the survival strategy of E.coli cells.

In this study, the major structural features of the MscS protein have been explored using PhoA fusions, precise deletions and site-directed mutations. Analysis by PhoA fusion suggests three TMS with an Nout–Cin topology. The data suggest that MscS is close to the minimum size for MscS activity and that perturbations of the structure strongly affect activity and stability. This sets the protein apart from the MscL channel, which tolerated larger deletions relative to the size of the protein (Blount et al., 1996a,b).

Results

Mapping the topology of MscS using PhoA fusions

PhoA fusion proteins have become an established technology for investigating membrane protein topology (Manoil, 1991; Boyd et al., 1993) and have been used to characterize bacterial channels (Blount et al., 1996a; Johansson and von Heijne, 1996; McLaggan et al., 2002). To facilitate this analysis for the MscS protein, BamHI sites were created at intervals along the gene using its hydrophobicity plot as a guide (Figure 1A). Eleven unique BamHI sites were created by site-directed mutagenesis, leading to changes in the amino acid sequence of the resultant MscS proteins (Table I). With the exception of the I48D/S49P double mutation and V253P, all modified MscS proteins exhibited the same ability as the wild-type MscS protein to protect strain MJF455 (MscS–MscL–) against hypo-osmotic shock (survival >90%; data not shown). Western blot analysis using anti-MscS antisera failed to reveal a protein band for strain V253P, whereas a stable protein was observed for the I48D/S49P double mutant (see below).

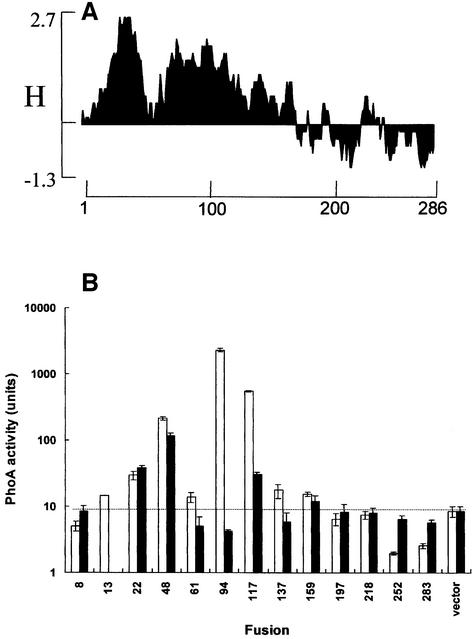

Fig. 1. Organization of the MscS protein. (A) Hydrophobicity plot of the E.coli MscS protein (w = 19 residues) generated using the DNASTAR suite of programs. (B) PhoA activity (mean ± SD) of uninduced stationary phase cultures of strain DHB4 bearing St (open bars) and NS (solid bars) fusions at the position indicated on the x-axis; note the log scale on the y-axis. All values are from replicate experiments in which three measurements were made of enzyme activity. The horizontal dotted line indicates the level of activity associated with strain DHB4 with no PhoA fusion protein. (C) Western analysis of expression of MscS–PhoA St fusions. Whole-cell preparations expressing different MscS(St)–PhoA fusions were separated by SDS–PAGE and western blots developed with anti-PhoA antibodies (4 ml of culture at OD650 = 0.4 were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in loading buffer and heated at 100°C for 10 min prior to separation on a 4–12% pre-cast SDS–polyacrylamide gradient gel). The protein sample for MscS94(St) was run out of numerical sequence to place it at a position where the intensity of the signal did not obscure the adjacent bands. (D) Proposed topology of the MscS protein based on the PhoA data. Symbols: +, positively charged amino acids; shaded circle, proposed periplasmically located residue 94.

Table I. Primers used to create BamHI sites or in cloning.

| Fusion sitea | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′)b | Amino acid changesc |

|---|---|---|

| D8 | (F) gATTTgAATgTTgTggATCCCATAAACggCgCg | S9P |

| (R) CgCgCCgTTTATgggATCCACAACATTCAAATC | ||

| A13 | (F) gCATAAACggggATCCAAgCTggCTgg | A13D, G14P |

| (R) CCAgCCAgCTTggATCCCCgTTTATgC | ||

| A22 | (F) ggTAgCTAACCAggATCCgCTgCTAAgTTATgC | A22D, L23P |

| (R) gCATAACTTAgCAgCggATCCTggTTAgCTACC | ||

| I48 | (F) CgCgCggATggATCCCAACgCggTg | I48D, S49P |

| (R) CACCgCgTTgggATCCATCCgCgCg | ||

| I61 | (F) gATCTCCCgTAAggATCCTgCCACTgTTgC | I61D, D62P |

| (R) gCAACAgTggCAggATCCTTACgggAgATC | ||

| A94 | (F) gggTgTACAAACggATCCAgTCATTgCTgTAC | A94D, S95P |

| (R) gTACAgCAATgACTggATCCgTTTgTACACCC | ||

| N117 | (F) ggggTCACTgTCggATCCggCCgCTggCgTg | N117D, L118P |

| (R) CACgCCAgCggCCggATCCgACAgTgACCCC | ||

| D137 | (F) gCCggAgAATATgTggATCCgggCggCgTAgCCg | L138P |

| (R) CggCTACgCCgCCCggATCCACATATTCTCCggC | ||

| D159 | (F) CCACCATgCgTACTgCggATCCTAAAATTATCgTTATTCCg | G160P |

| (R) CggAATAACgATAATTTTAggATCCgCAgTACgCATggTgg | ||

| D197 | (F) ggCgTATgATTCggATCCCgATCAggTTAAgC | I198P |

| (R) gCTTAACCTgATCgggATCCgAATCATACgCC | ||

| D218 | (F) gATCgCATTTTgAAggATCCCgAAATgACTgTgCgC | R219P |

| (R)gCgCACAgTCATTTCgggATCCTTCAAAATgCgATC | ||

| D252 | (F) CgTgTACTgggATCCgCTggAgCgTATTAAACg | V253P |

| (R) CgTTTAATACgCTCCAgCggATCCCAgTACACg | ||

| D283 | (F) gCgggTgAAAgAggATCCAgCTgCgTAATCAACgC | K284P |

| (R) gCgTTgATTACgCAgCTggATCCTCTTTCACCCgC | ||

| MscKIM | (F1) CgTTCCCACCATggCACTggAgCAAg | |

| (R1) CgTTCACTCgAgCCCTACCgCTggCgTC | ||

| Ypet3 | TagATgCATATggAAgATTTgAATgTgTC | |

| Ypet4 | TagATgCTCgAgCgCAgCTTTgTCTTCTTTC | |

| YPNco | TagATgCCATggAAgATTTgAATgTTgTCg | |

| YM2R | GTTTTggATCCACATCAAgTTgCCC | |

| HHd3 | TTTgTTAgCAAgCTTATCAgTggTggTggTggTgg |

aThe site is defined by the amino acid residue that is converted to aspartate by creation of the BamHI site.

bRestriction sites incorporated into the primers are indicated in bold.

cAmino acid changes are those caused by creation of the BamHI site, which always changes the wild-type sequence to aspartate–proline.

PhoA fusions were made both as C-terminal truncations of the MscS protein (St) and as sandwich fusions (NS) by insertion of a ‘phoA’ gene cassette that either possesses a nonsense mutation or fuses in-frame at the 3′ end (Blount et al., 1996a). Only one construct failed consistently to form a PhoA fusion; a sandwich fusion at residue 13 could not be recovered. Successful insertions at this position were obtained in the reverse orientation, suggesting that the fusion protein that would be formed by the correct orientation is toxic. The successful clones were transformed into DHB4 (ΔphoA) (Table II) and assayed, without prior induction, for PhoA activity. One clone, MscS94(St), gave strong PhoA activity on LB plates containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-phosphate (XP), and three further clones, MscS48(St), MscS117(St) and MscS159(St), exhibited lower activity. All other St fusions were inactive. Only two NS fusions were active on LB-XP plates, MscS48(NS) and MscS117(NS). These data were confirmed by cell assays, which revealed that the highest activity in both exponential (data not shown) and stationary phase was associated with MscS94(St) (Figure 1B). Fusions MscS48(St), MscS117(St) and MscS159(St) gave 10- to 30-fold less activity (Figure 1B). Fusion MscS94(St) gave the strongest signal on western blots with anti-PhoA antisera, followed by MscS117(St) and MscS283(St) (Figure 1C). Low levels of accumulation of other protein fusions were observed, except for MscS8(St) and MscS218(St), which could not be detected. The PhoA activity of NS fusions at positions 94 and 117 was significantly lower than the St fusions, and in particular that at position 94 exhibited only background activity (Figure 1B). All of the NS fusion proteins were very unstable, and western blotting with anti-PhoA antibodies only detected the extreme C-terminal, MscS283(NS), fusion (data not shown). These data suggest that only MscS94(St) is located at the periplasmic surface of the membrane, but that MscS48(St) and MscS117(St) can generate some fusion protein that is located in the periplasm. In-frame non-stop fusions tended to destabilize the MscS protein, in contrast to the observations made with MscL–PhoA fusions where the NS and St fusions were essentially equivalent (Blount et al., 1996a). Our data suggest that MscS is much more sensitive to structural perturbation than MscL.

Table II. Strains and plasmids.

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MSD2252 | Δlac, DE3 (T7 polymerase expressed from lacUV5 promoter) | Rob Hockney |

| Frag1 | F–, rha, thi, gal, lacZ | Epstein and Kim (1991) |

| MJF429 | Frag1, ΔmscS, ΔmscK::kan | Levina et al. (1999) |

| MJF455 | Frag1, ΔmscL::Cm, ΔmscS | Levina et al. (1999) |

| MJF465 | Frag1, ΔmscL::Cm, ΔmscS, ΔmscK::kan | Levina et al. (1999) |

| DHB4 | F′ lac pro lacIq/Δ(ara leu)7697 araD139 Δ(lac)X74 galE galK rpsL phoR Δ(phoA)PvuII Δ(malF)3 thi | Boyd et al. (1987) |

| JM109 |

endA1, recA1, gyrA1, gyrA96, thi, hsdR17, (rk-, mk+), relA1, supE44, λ–, Δ(lac- proAB), [F′, tra36, proAB, lacIQ, ΔM15] |

Sambrook et al. (1989) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTrc99A | Cloning vector | Pharmacia |

| pETMscS | pET21b carrying mscS—expression under the control of T7 polymerase | This study |

| pMscS | mscS cloned into pTrc99A. This plasmid contains no BamHI sites | This study |

| pMscSH6 | mscS cloned into pTrc99A with an in-frame His tag at the C-terminus | This study |

| pMscSXN, e.g. pMscSI48 | pBS10 mutated to carry BamHI site at residue X (amino acid) N (residue no.), using primers listed in Table I | This study |

| pMscSXN(St), e.g. pMscSI48(St) | Carries phoA stop cassette fused to residue X (amino acid) N (residue no.) | This study |

| pMscSXN(NS), e.g. pMscSI48(NS) | Carries phoA non-stop cassette fused to residue X (amino acid) N (residue no.) | This study |

| pMscSΔN1-N2, e.g. pMscSΔ8–22 | Carries mscS with internal in-frame deletion coding for mscS lacking amino acids N1 to N2 | This study |

| pMscKIM | pTrc99A bearing residues 774–1120 of MscK | This study |

The positions of the MscS48(St) and MscS117(St) fusions are N-terminal of putative loops that contain the main clusters of positive charges (R54, R60, K61, and R128, R131), which should anchor these sequences at the cytoplasmic face of the membrane (Figure 1D) (von Heijne, 1992). It seemed likely that residues I48 and N117 should be cytoplasmically located, but the fusions misreport their location due to loss of the anchoring positive charges. To test this, fusions were created C-terminally to the positively charged sequences, thus creating MscS61(St) and MscS137(St). Both pMscS61 and pMscS137, which carry mutations created by insertion of the BamHI site (Table I), expressed mutant proteins that complemented the osmotic lysis phenotype of MJF455 (survival >90%). The PhoA(St) and (NS) fusion proteins formed at these positions displayed low alkaline phosphatase activity (Figure 1B), suggesting that the presence of the positive-charged clusters just prior to the fusion junction was sufficient to retain PhoA in the cytoplasm. These data are accommodated most readily in a model of MscS that possesses three TMS with an Nout–Cin orientation, which would place the soluble domain (residues 117–286) in the cytoplasm.

Deletion analysis of MscS

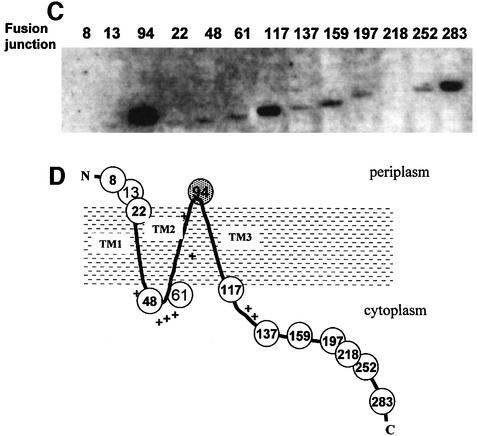

The members of the MscS family vary in size, with exten sions at both the N- and C-terminus relative to E.coli MscS (Levina et al., 1999; Pivetti et al., 2003). At 286 residues E.coli MscS is one of the smallest homologues reported to date. In-frame internal deletions were made using the previously engineered BamHI sites, and the ability of the resultant proteins to complement strain MJF455 in hypo-osmotic shock assays was determined (Figure 2A). Strains MJF455/pMscSΔ8–12 and MJF455/pMscSΔ8–21 survived hypo-osmotic shock, whereas MJF455/pMscSΔ8–47 and MJF455/pMscSΔ8–60 did not (Figure 2A). A stable protein was encoded by plasmid pMscSΔ8–12, while that for pMscSΔ8–21 was reduced to the limit of detection of the western blot (i.e. 8- to 10-fold reduction in expression compared with fully induced MscS) and the major stable product was ∼17 kDa (Figure 2B). Larger deletions (Δ8–47 and Δ8–60), which removed sequences that should form the first TMS, did not yield stable proteins (Figure 2B). Deletion constructs affecting the C-terminus (Δ218–251, Δ252–282 and Δ218–282) were inactive in the complementation assay (Figure 2A) and no protein was detected by western blotting (Figure 2B). A short deletion MscSΔ252–261, internal to the C-terminal domain, also failed to complement strain MJF455 in the hypo-osmotic shock assay (data not shown). These data suggest that almost the whole of the MscS protein is required for activity and stability.

Fig. 2. The C-terminal domain of MscS is essential for stability and activity. In-frame deletions were created in the N- and C-terminal domains of MscS as described in Materials and methods. (A) The ability of pMscS deletion plasmids to complement the MS channel defi ciency of strain MJF455 was assayed as described in Materials and methods. Data shown are the mean ± SD of replicate experiments. (B) Expression of MscS deletion mutants. Cells were grown in LB medium and induction of protein expression achieved by the addition of 0.3 mM IPTG for 30 min. Membrane fractions were prepared by harvesting cells, and cell breakage was achieved by passage through a French pressure cell. Membrane fractions were harvested by centrifugation at 100 000 g in a Beckmann TL-100 benchtop ultracentrifuge. Membrane proteins (15 µg/track) were separated on a Novex pre-cast 4–12% gradient SDS–polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose as described previously (McLaggan et al., 2001). The blot was exposed to anti-MscS antibodies raised against the peptide sequence 126–141 (MRPFRAGEYVDLGGV), which lies in the C-terminal domain.

Mutational analysis of MscS

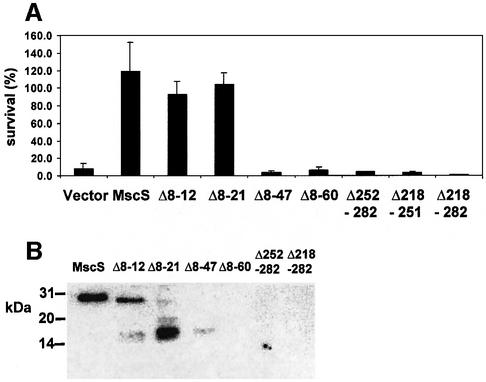

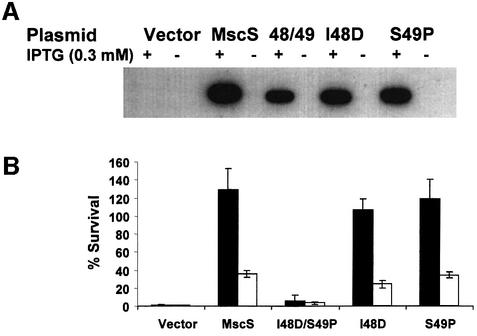

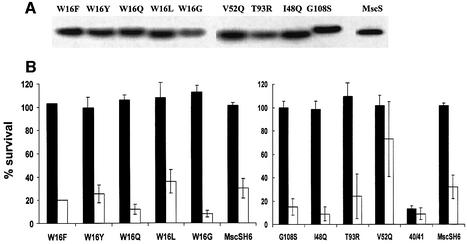

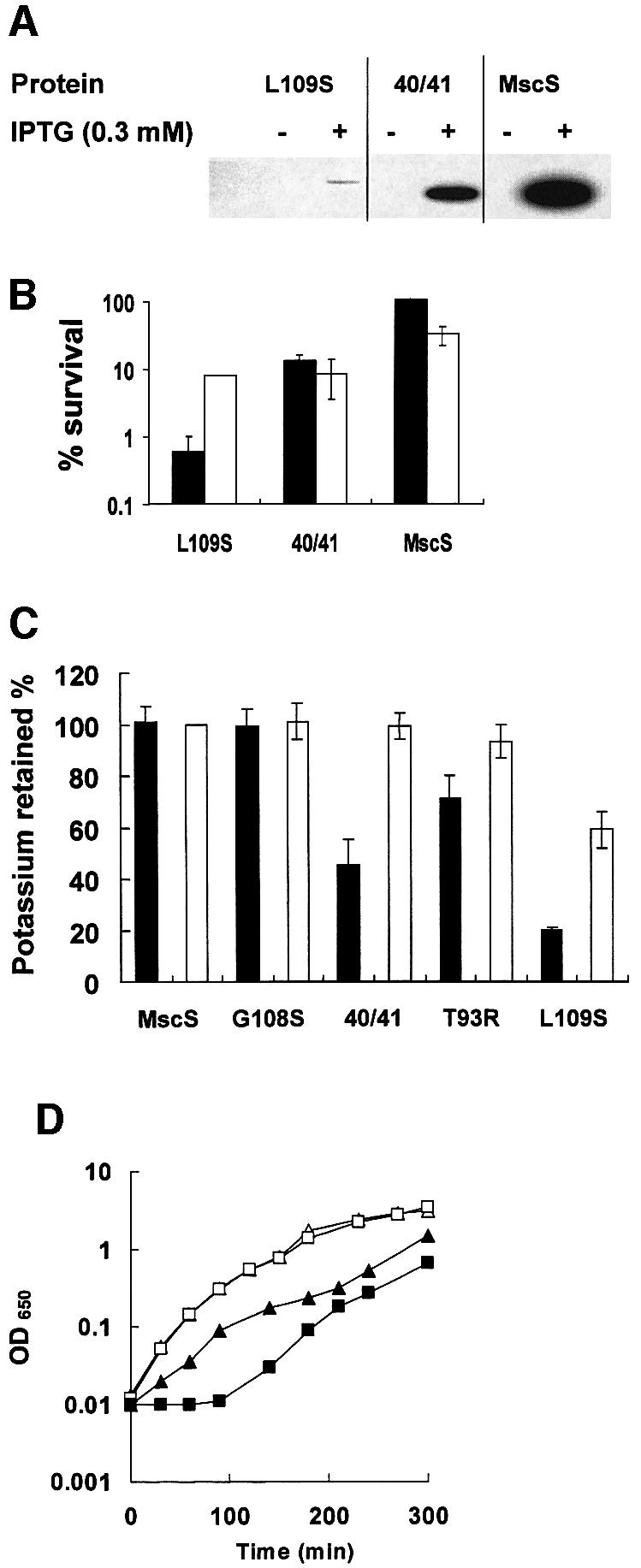

Prior to determination of the crystal structure, considerable progress was made in the analysis of the structure and gating of the MscL channel by the analysis of mutations that influence channel activity (Blount et al., 1996b, 1997; Ou et al., 1998). We have followed a similar strategy with MscS. The influence of mutations on MscS has been analysed by western blotting to assess stability relative to the parent protein, by their effects on K+ retention, by their ability to form colonies on broth agar containing either low (∼8 mM) or high (∼90 mM) K+, using electrophysiological analysis, by their sensitivity to cationic antibiotics (kanamycin and neomycin) and by their ability to complement the channel deficiency in strain MJF455 (MscS–MscL–). In this last assay, uninduced wild-type MscS increases survival from <5% to 30–40%, with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-induced ex pression increasing survival to 100% (Figure 3B). Only after induction is the protein readily detectable by western blots (Figure 3A).

Fig. 3. A double mutant MscS I48D/S49P inactivates MscS but does not significantly impair expression. The double mutant I48D/S49P (indicated as 48/49 in the figure) was constructed during the introduction of BamHI sites into pMscS, and the single mutants were made subsequently using the Quickchange mutagenesis protocol. (A) Expression of the altered protein was determined by western blotting of membrane proteins using anti-MscS antibodies as described in Figure 2B. (B) The ability of pMscS mutant plasmids to complement the MS channel deficiency of strain MJF455 was assayed as described in Materials and methods. Data shown are the mean ± SD deviation of replicate experiments. Filled bars, cells induced with 1 mM IPTG for 30 min; open bars, uninduced cells.

I48D/S49P. The I48D/S49P mutant was created while making BamHI sites for PhoA analysis and failed to complement strain MJF455 in the hypo-osmotic shock survival assay. Single mutations, I48D and S49P, did not significantly reduce MscS activity in hypo-osmotic shock assays (Figure 3B), and the mutant proteins were incorporated into the membrane (Figure 3A). Given the apparent loss of function of the I48D/S49P double mutant, further rounds of mutagenesis affecting I48 and S49 to create single mutants were carried out. A range of substitutions could be made (I48 to V, T, G, H and A, and S49 to L, T, G, R, Y, D, V, F and C) without affecting the ability of the protein to complement the osmotic lysis phenotype of MJF455 (data not shown). Only MscM channel activity was found in membrane patches bearing the I48D/S49P mutant (n = 4), expressed in strain MJF465 (MscS–MscK–MscL–), despite the application of pressures expected to activate MscS. These data, when coupled with the expression and complementation analyses, suggest that the I48D/S49P double mutation causes a loss of function.

W16X. Tryptophan residues have been implicated in the organization of membrane proteins (White and Wimley, 1999). MscS has a single tryptophan residue in the N-terminal domain (W16) and this was changed to Y, Q, F, G or L. After induction with IPTG, the proteins were readily detectable in the membrane and only W16G was expressed to a lesser extent than either the wild type or other mutants (Figure 4A). When induced, all the mutant proteins complemented strain MJF455 in the hypo-osmotic shock assay (Figure 4B), suggesting that this residue is not essential for activity. However, similar experiments with the uninduced W16 mutants revealed reduced protection of MJF455 cells, e.g. W16G and W16Q (Figure 4B). Hydrophobic substitutions were equivalent to wild type, suggesting that while the tryptophan is not essential, a hydrophobic residue is preferred at this position.

Fig. 4. Expression and activity of MscS mutant proteins. Single mutations were made in pMscSH6 at the relevant position using Quickchange mutagenesis. (A) The expression of the mutant proteins was determined by western blotting of membrane proteins, as described in Figure 2B using anti-His6 antibodies. (B) The ability of pMscSH6 mutant plasmids to complement the MS channel deficiency of strain MJF455 was assayed as described in Materials and methods. Data shown are the mean ± SD of replicate experiments. Filled bars, cells induced for expression of the MscS mutants by incubation with 0.3 mM IPTG for 30 min; open bars, data from uninduced cells.

Gain-of-function (GOF) mutations. GOF mutants have been isolated in MscK of Salmonella typhimurium (H.Jeong and J.Roth, personal communication). We there fore created the equivalent amino acid changes in MscS (I48Q, V52Q, T93R, A102P, G108S and L109S). As a control, the published GOF mutation in MscS (V40D/G41S; Okada et al., 2002) was created. Three mutants, I48Q, G108S and V52Q, were expressed normally (Figure 4A), complemented MJF455 in the hypo-osmotic shock assay (Figure 4B) and formed healthy colonies on both LB and LK agar plates (data not shown). By physiological criteria, these mutant proteins formed normal channels. Induction of V40D/G41S expression inhibited growth in liquid (LB) medium (data not shown; Okada et al., 2002), caused K+ leakage after induction (Figure 5C) and impaired colony formation on LB and LK agar plates, consistent with a GOF phenotype (data not shown). Two further GOF mutants were detected by this screen: L109S and T93R inhibited growth on both LB and LK plates, with L109S affecting growth even in the absence of induction. Both wild-type and a mutant, G108S, grew normally on both LB and LK. In liquid medium, induction of T93R expression did not impair growth in either broth or minimal medium, but cells expressing even basal levels of L109S would not grow in minimal medium when inoculated from a single colony (data not shown). Induction of L109S in complex medium caused transient growth inhibition, but the cell subsequently recovered (Figure 5D). During steady-state growth, expression of T93R and L109S caused impaired retention of the K+ pool, consistent with GOF in the MscS channel (Figure 5C). This effect was evident for both uninduced and induced cells expressing L109S, suggesting that this mutant causes a severe GOF relative to V40D/G41S and T93R. The L109S mutant protein is expressed very poorly compared with other MscS channel mutants (Figures 5A), which suggests that the channel is highly active. Consistent with this, neither L109S nor V40D/G41S were able to complement MJF455 in the hypo-osmotic shock assay. Induction of L109S reduced the survival of MJF455; in contrast, induced expression of other mutant proteins enhanced survival after hypo-osmotic shock (Figures 4B and 5B). Electrophysiological examination of L109S in strains MJF455 (MscS–MscL–) and MJF465 (MscS–MscK–MscL–) has presented MscS-like channels, based on conductance and pressure threshold, but in low abundance, which is consistent with the poor expression levels (n = 4/18 patches; data not shown). All putative GOF mutants increased the sensitivity of MJF455 to kanamycin and neomycin relative to that shown by the parent and representative non-GOF mutants, consistent with impairment of growth.

Fig. 5. A GOF mutation L109S causes protein instability and loss of complementation of the MS channel defect of MJF455. Mutations were created in plasmid MscSH6 by the Quickchange protocol. (A) Western blots were performed on membrane proteins harvested either without induction or after 30 min incubation with 0.3 mM IPTG. The reduced expression of mutant 40/41 (V40D/G41S) is partially due to the immediate and complete inhibition of growth upon addition of IPTG, which may impair protein synthesis. Note that the blot has been overexposed relative to equivalent data in Figures 2–4 to allow the weak band associated with YggB L109S to be visible. (B) The ability of the mutant proteins to complement the MS channel deficiency was assayed as described in Materials and methods. Data shown are the mean ± SD of replicate experiments. Filled bars, cells induced for expression of the MscS mutants by incubation with 0.3 mM IPTG for 30 min; open bars, data from uninduced cells. (C) K+ pools of cells expressing different MscS alleles were measured as described in Materials and methods. (D) Growth of MJF455/pMscSH6 (open symbols) and MJF455/pMscSL109S (closed symbols) in LK medium. Cells were grown in the presence (squares) or absence (triangles) of 1 mM IPTG, which was added at zero time.

The A102P mutation could not be created in plasmid pMscSH6, possibly due to the significant levels of basal expression in strain MJF455. The mutation was created readily in a different vector, pETMscS, which is not expressed in the absence of T7 polymerase. Strain MSD2252 carries the T7 polymerase integrated into the chromosome and expressed from the IPTG-inducible lacUV5 promoter. Previous work in this laboratory has shown that this strain expresses very low levels of T7 polymerase in the absence of the inducer (McLaggan et al., 2002). Using this system we found that colony formation, on both LB and LK, was inhibited by basal levels of expression of A102P (fewer and smaller colonies compared with MJF455 cells carrying either pETMscS or pMscSH6). Colony formation, by MSD2252 expressing A102P, was completely inhibited by the presence of IPTG. These data suggest that the A102P mutation causes an extreme GOF phenotype, even when expressed at the low levels associated with uninduced expression from pMscSH6.

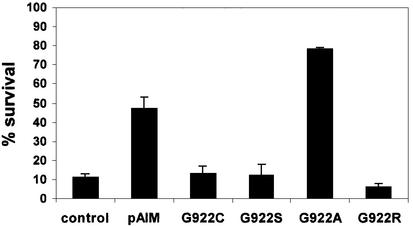

A truncated MscK (MscKIM) can substitute for MscS in hypo-osmotic shock survival

MscK is a multidomain protein, which at its C-terminal end resembles MscS (Levina et al., 1999; McLaggan et al., 2002). The strong organizational similarity between MscK and MscS suggested that the channel component of MscK might reside in the equivalent domains. The C-terminal domains of MscK were amplified by PCR (from residue 774 to 1120) and expressed in pTrc99A to create pMscKIM (IM = second inner membrane domain). Induction of expression of the MscKIM protein in strain MJF455 caused survival to increase from 11 ± 2% to 47 ± 6%, suggesting the presence of MS channel activity (Figure 6). Similar data were obtained with transformants of strain MJF465 (MscS–MscK–MscL–) (Levina et al., 1999), from which it can be deduced that the protection given by the truncated MscK protein does not require full-length chromosomally encoded MscK (data not shown). A number of point mutations were made in this construct at amino acid 922, the residue implicated in altered gating of MscK (McLaggan et al., 2002). Three mutations, G922S, G922R and G922C (numbering for full-length E.coli MscK), led to loss of complementation by the MscK protein, whereas G922A increased the capacity of the protein to prevent the lysis of MJF455 upon hypo-osmotic shock (Figure 6). No channel activity associated with MscKIM could be detected by patch–clamp analysis of MJF465/pMscKIM or MJF429/pMscKIM (n = 13) (Table II), despite the observation of MscM in both strains and MscL in MJF429. Full-length MscK is also difficult to assay by electrophysiology, being present in a minority of patches (Levina et al., 1999; Li et al., 2002).

Fig. 6. The C-terminal domains of MscK complement the MS channel deficiency of strain MJF455. Cells expressing pMscKIM with or without mutations at G922 were grown in McIlvaine’s medium (Levina et al., 1999) and diluted 20-fold into milli-Q water; after 10 min, samples were taken for viable counts as described in Materials and methods. Plasmids were induced with 1 mM IPTG for 1 h prior to assay. Data are the mean ± SD from replicate measurements.

Discussion

The data presented here are consistent with the organization of the MscS channel protein into three TMS, Nout–Cin, which is the structure predicted from application of the positive-inside rule for membrane proteins (von Heijne, 1992). This model is reinforced by the finding that two PhoA fusions, MscS48(St) and MscS117(St), which appear to contradict the three TMS model, are cytoplasmic when the positively charged cytoplasmic loops of MscS are included in the fusion protein. The Methanococcus jannaschii MS channels MscJ and MscMJLR have also been predicted to have three TMS based on the hydrophobicity analysis, but no supporting biochemical or genetic analysis has been performed (Kloda and Martinac, 2001). Recent work has shown that MscS is probably hexameric (Sukharev, 2002). It seems extremely likely that this organization may explain the difficulty in obtain ing stable sandwich fusions between MscS and PhoA. The lack of activity and stability of the MscS94(NS) fusion compared with MscS94(St) may indicate that the latter has lost the oligomeric structure associated with the native channel.

Deletion analysis suggests that the MscS protein is close to the minimal size for an MscS-type channel. The N-terminal region between residues 8 and 12 is dispensable. This observation is consistent with the lack of conservation of the N-terminus in the MscS family of proteins, which varies from 14 to 45 residues (21 residues in E.coli MscS). In the wider family of MscS-related proteins, several additional membrane regions may be found N-terminal to TMS1, suggesting considerable structural variability in the family (Pivetti et al., 2003). A larger deletion, Δ8–21, forms functional channels despite being less stable in the membrane than the Δ8–12 deletion (Figure 2). Notably, however, we could not create an in-frame sandwich fusion at residue 13, which suggests that insertions at this specific position may severely disrupt the protein. More extensive deletions, which remove the first TMS, cause loss of function, and only protein fragments are detectable in the membrane (Figure 2). Deletions at the C-terminus were not tolerated; even the smallest deletion of 31 amino acids caused loss of the protein from the membrane and consequent inability to complement the double channel mutant strain, MJF455 (Figure 2). Given that relatively little channel protein is required for complementation (Figure 3A and B), these data suggest a major loss of function associated with C-terminal deletions, despite the relatively low level of absolute sequence conservation in this domain (Touze et al., 2001).

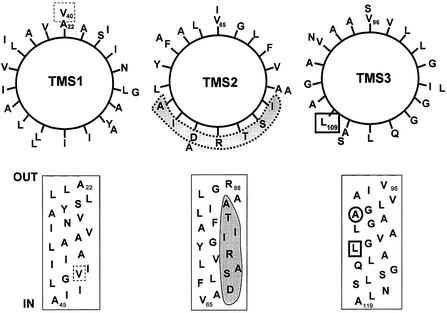

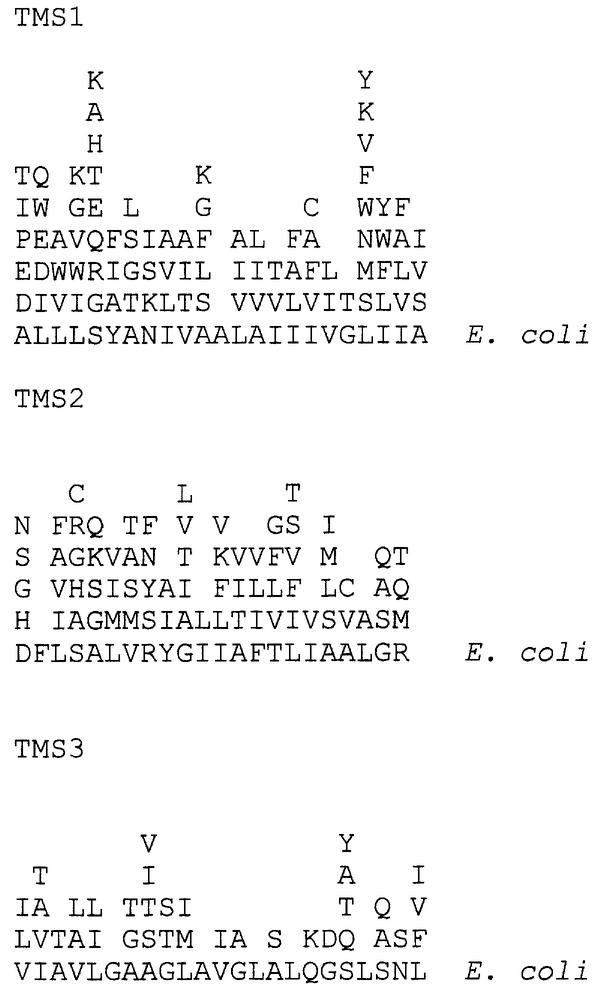

The proposed structure of the MscS monomer is three transmembrane helices with a long cytoplasmic loop (∼20 residues), a short periplasmic loop (∼8 residues) and a large C-terminal domain (Figure 1D). The double mutation that impairs channel activity, I48D/S49P, lies just at the start of the cytoplasmic loop. The characters of the three transmembrane helices differ significantly (Figure 7). TMS1 is predicted to be hydrophobic and, with the exception of A34 and V40, individual residues are not strongly conserved, but the character of each position is maintained (Figure 8). Adjacent clusters of small amino acids (A) and larger hydrophobic residues (I and V) are of possible structural significance, since they could form knobs and grooves for helix interactions during channel gating, as proposed for MscL (Sukharev et al., 2001b). TMS2 is truly amphipathic: one face is lined with D, S, R, A and T (Figure 7). Conservation of the sequence is not strong, but the natural substitutions made in this helix within the MscS subfamily are predominantly hydrophilic (Figure 8). The hydrophilic character of the residues in this helix suggests that it may line the channel pore. TMS3 is also predominantly hydrophobic, but has a cluster of hydrophilic residues towards the cytoplasmic surface. It is notable that this helix carries a series of glycine residues that might be required for conformational flexibility, such as is required to open the MthK K+ channel (Jiang et al., 2002).

Fig. 7. Organization and character of putative transmembrane helices in MscS. The three proposed transmembrane helices are represented as both helical wheels and planar depictions. Residues V40 (dashed box), A102 (circle) and L109 (box) have been shown to generate a GOF phenotype (Okada et al., 2002; this study). T93R lies on the putative periplasmic loop between TMS2 and TMS3. The amphipathic nature of TMS2 is emphasized by shading of the hydrophilic residues.

Fig. 8. Conservation within the three putative transmembrane helices. Following the analysis of conservation of amino acids in the transmembrane spans of MscL (Sukharev et al., 2001b), we aligned the amino acid sequences of the YggB subfamily of MscS proteins (subfamily VI of Pivetti et al., 2003) and here we depict the degree of conservation of TMS1, TMS2 and TMS3. The sequence of the three proposed transmembrane helices from E.coli MscS are shown, and immediately above each residue the observed replacements found in other members of the family are given. The sequences were aligned using the Clustal program, and the observed permitted substitutions recorded. Where a residue is 100% conserved, no other amino acid is indicated above the E.coli MscS sequence. The members of the subfamily are the YggB homologues from (organism and DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No.): Edwardsiella ictaluri (AF037440), Buchnera sp. APS (11387303), Vibrio cholerae (11278432), Pseudomonas aerogenes (11348170), Syneccocystis (2501529), Xylinella fastidiosa (11362678), Neisseria meningitidis (11278435), Mesorhizobium loti (13473416), Caulobacter crescentens (13425360) and Helicobacter pylori (7444700).

All MS channels must share the property that they are tightly sealed and must open rapidly in response to sudden increases in turgor. Genetic analysis of E.coli MscL led to an understanding of the importance of the hydrophobic lock, V23, in maintaining the channel closed under iso-osmotic conditions (Ou et al., 1998). Recently, Blount and colleagues isolated a GOF mutant in MscS at residue 40 that exhibited a similar phenotype, which led them to propose that this residue plays a similar ‘locking’ role in MscS (Okada et al., 2002). Only V40K and V40D substitutions caused a significant GOF phenotype; other changes, even changes to mildly hydrophilic residues and to glycine, were tolerated. In this study, we have identified three new MscS GOF alleles, T93R, L109S and A102P, which are in the periplasmic loop and TMS3. These positions were identified originally in MscK from a random screen for mutations that alter the threshold for quinolinic acid supplementation in nadA auxotrophs of S.typhimurium (H.Jeong and J.Roth, personal communication). The phenotypes of the mutants were consistent with GOF in the channel. Thus, similar positions in MscK and MscS can alter channel gating, suggesting that despite the differences in sequence and organization of the proteins, the gating mechanisms have retained common components. This is supported further by the observation that the truncated MscK channel, MscKIM, can complement the channel deficiency of MJF455 (MscS–MscL–) (Figure 6). Similarly, amino acid changes in MscKIM at the position equivalent to MscK G922S alter channel activity (Figure 6). Four GOF mutants have been identified in MscS (three in this study and one previously). In MscL, GOF mutations of differing degrees of severity were found in the S1 helix, TM1, TM2 and the periplasmic loop (Blount et al., 1996b, 1997). The pattern in MscS appears to repeat that found in MscL and should inform the generation of models for the structure and gating of MscS.

Finally, our studies have shown that GOF mutations in MscS may have very severe consequences for the cell. The random screen for GOF mutants that has been reported recently (Okada et al., 2002) may have failed to identify foci for such mutations due to the ease of attaining a permanent open state of this channel, which would cause cell death. Sukharev et al. (2001a,b) have suggested that MscL makes transitions that break the hydrophobic seal but do not open the channel, since the movement of the N-terminal helix S1 from the base of the expanded state of the channel is the final event in opening. Others have questioned this view, suggesting that the hydrophobic seal may be broken in concert with movement of the S1 helices as a single conformational change (Kong et al., 2002). This complexity of the MscL conformational change from closed to open state may have facilitated the isolation of GOF mutations because such mutants still gate in response to pressure, i.e. the impact of mutations that affect the hydrophobic seal is diminished by the presence of a second gate element (Sukharev et al., 2001a). It is clear that MscS is a more complex protein than MscL at all levels, but it is an intriguing possibility, consistent with the data presented here, that this channel has a single gate and consequently is much more susceptible to structural perturbation. Whilst GOF mutations are an important strategy, the isolation of loss-of-function mutants, such as I48D/S49P, may offer better insights into the critical domains of the MscS channel.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table II. DHB4 was kindly provided by Paul Blount (Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, TX). Strains were grown routinely at 37°C in Luria–Bertani medium (LB) containing per litre: 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of NaCl and 5 g of yeast extract. Medium was supplemented with ampicillin (25 µg/ml) if required. LK medium contains 6.4 g of KCl in place of the NaCl. Agar plates contained 14 g/l agar.

DNA manipulations and site-directed mutagenesis

DNA manipulation was carried out using standard techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989). Plasmid preparations were made using Qiagen Spin mini-prep columns as instructed by the manufacturer. Point mutations were introduced into either pMscS, pMscSH6 or pETMscS (Table II). Plasmid pTrcMscS was used as the basis for construction of pMscS and was made by PCR amplification of the mscS gene from Frag1 using primers YPNco and YM2R, which incorporate NcoI and BamHI sites, respectively. The PCR product was purified, Klenow treated and digested with NcoI and BamHI prior to ligation into similarly digested pTrc99A (Amann et al., 1988). Plasmid pTrcMscS was digested with BamHI and SalI, which lie 3′ to the mscS gene, the ends filled by Klenow treatment and the plasmid re-ligated to create pMscS, which contains no BamHI sites. Plasmid pETMscS was created by PCR amplification of the mscS gene with NdeI and XhoI sites incorporated into the forward and reverse primers (Ypet3 and Ypet4), respectively. The amplified DNA was purified, treated with Klenow, digested with NdeI and XhoI, and ligated into pET21b (Pharmacia) that had been treated similarly. Plasmid pMscSH6 was constructed by PCR amplification of the ∼400 bp 3′ to the native PstI site in pETMscS and incorporating the 3′ vector-encoded His-tag sequence (amino acid sequence LEHHHHHHstopstop). The reverse primer HHd3 introduced a HindIII site, and the amplified fragment was purified, Klenow-treated, digested with PstI and HindIII, and ligated into similarly digested pMscS. The new plasmid was sequenced on both strands, and expression of a His-tagged membrane protein of the correct mass verified by western blotting. Plasmid pMscKIM was constructed from pNL3 (McLaggan et al., 2002) and was designed to encode the C-terminal 346 amino acids of MscK. An internal NcoI site was removed using Quickchange mutagenesis (primer sequence available on request). The 3′ end of the mscK gene was then amplified using primers MscKIMF1 and MscKIMR1 (Table I), which incorporate NcoI and XhoI sites, respectively. The amplified DNA was digested with NcoI and XhoI and cloned into pTrc99A (Amann et al., 1988), and the insert sequenced on both strands.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the Stratagene Quickchange Site-Directed Mutagenesis protocol. Mutagenic primer pairs to make BamHI sites in the mscS gene are listed in Table I; the sequences of other mutagenic primers are available on request. In general, mutagenic primers were designed to produce not only the desired mutation but also a change in the restriction enzyme profile of the desired construct to aid selection. All primers used in this study were manu factured by Sigma-Genosys. Sequencing was carried out using an ABI BIG-DYE sequencing kit as instructed. The BamHI phoA cassettes used to create the mscS–phoA fusions were obtained from P.Blount (Southwestern University Medical School, Dallas, TX) (Blount et al., 1996a). Plasmid pMscS was used as the template in separate site-directed mutagenesis reactions to create a set of 13 mscS mutants with unique BamHI sites inserted at the desired position for subsequent fusion to a phoA cassette. In each mutant, the reading frame of the BamHI site was such that proline was always inserted after an aspartate residue (i.e. ggAT CC), ensuring that insertion of the phoA cassette would create an in-frame fusion of MscS to PhoA. Each BamHI mutant was sequenced fully on both strands to ensure that no mutations other than those desired had been introduced. A 1.4 kb BamHI phoA cassette, with either stop codons or sense codons at the 3′ end to create terminated (i.e. stop) fusions and non-stop fusions, respectively (Blount et al., 1996a), was cloned into the mscS BamHI mutant plasmids. The orientation of the cassette in each clone was determined by restriction digestion, and both fusion junctions in each clone were verified by sequencing across the junction regions.

All plasmids bearing deletion constructs, with the exception of pMscSΔ252–261, were created from the BamHI mutants used for the PhoA fusions by standard cloning techniques. For example, pMscSΔ8–12 was created by digestion of plasmid pMscS8 with BamHI and HindIII, then inserting the purified BamHI–HindIII fragment from pMscS13, which creates an in-frame deletion of residues 8–12 inclusive. Similar approaches were taken for the other deletion constructs, with the exception of pMscSΔ252–261. This plasmid was created in two steps. Plasmid pMscS252 was used as the template in a site-directed muta genesis reaction using primers MscS261BamHI-1 and MscS261BamHI-2 (sequences available on request). Due to the close proximity of the two desired BamHI sites, colonies from the mutagenesis reaction were screened by sequencing across the target region and a clone possessing the two desired BamHI sites was selected. This plasmid was digested with BamHI and then re-ligated to produce MscSΔ252–261. The construction of the deletion clone was again verified by sequencing.

Gene and protein sequences were analysed using the DNAstar suite of programs, and membrane protein topology prediction also used the SOSUI site (http://sosui.proteome.bio.tuat.ac.jp/). Sequence comparisons used the BLAST program (Altschul et al., 1997) at the NCBI site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Generation of antibodies and western blots

Peptide-specific antibodies were generated to MscS using the DNAStar suite of programs to guide selection of regions with a high probability of being strong antigens. The peptides were synthesized, conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA) and antibodies raised in rabbits by Sigma-Genosys. The antibodies were affinity purified by conjugating the peptide, via an N-terminal cysteine residue, to maleimide–Sepharose using the Sulfolink kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibodies were aliquoted and frozen at –20°C until required and used in western blots at ∼1 µg/ml. PhoA antibodies were the generous gift of Dr H.de Cock (University of Utrecht, The Netherlands). Anti-His6 antibodies (mouse IgG2a isotype) were obtained from Sigma. Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were either Pierce Immunopure goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) or Sigma goat anti-mouse IgG (whole molecule). Western blots were performed on membrane fractions as described previously (Towbin et al., 1979), with the exception that pre-formed SDS–polyacrylamide gels (Novex) were used to separate the proteins prior to transfer onto nitrocellulose. The protein concentration in membrane preparations was assayed by the Folin–Ciocalteau method (Lowry et al., 1951). Images were developed using Pierce enhanced chemiluminescence (Supersignal Dura substrate), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and were analysed using a Kodak Image station 440CF.

Determination of PhoA activity

The PhoA activity of each fusion clone was assayed both on solid media and by enzymatic assay. All fusion clones were transformed into the phoA mutant strain, DHB4 (Table II). PhoA activity in the transformants was assayed on plates by observing the colour of colonies after 18 h growth on LB plates containing ampicillin (25 µg/ml) and XP indicator (40 µg/ml) (1 mM IPTG was included if required). PhoA activity in cells was assayed by measuring the rate of p-nitrophenyl phosphate hydrolysis in permea bilized cells (Brickman and Beckwith, 1975; Michaelis et al., 1983). Data were obtained from uninduced cultures in both logarithmic and stationary phase.

Growth experiments, analysis of cell viability and measurement of K+ pools

For analysis of GOF phenotypes, the ability of cells to grow on LB medium containing ampicillin in the presence or absence of IPTG was scored (Blount et al., 1996b). In some experiments, cells were diluted immediately after recovery from transformation and spread on LB or LK plates containing ampicillin in the presence or absence of 1 mM IPTG, and growth scored 16–20 h after inoculation. GOF was also analysed in liquid medium by following the OD650. For downshock assays, strain MJF455, bearing different plasmids, was grown to OD650 = 0.4 in LB + 0.5 M NaCl and then diluted 10-fold into LB medium. After 10 min, the number of viable cells was determined by serial dilution and spreading triplicate 5 µl aliquots on LB agar. Control incubations were performed in which dilution and survival were assayed using LB + 0.5 M NaCl. In some experiments, growth and downshock were conducted using minimal medium as described previously (Levina et al., 1999) and cells were diluted into distilled water (see Figure 6 legend). Sensitivity to kanamycin and neomycin was assayed by spreading MJF455 cells carrying either wild-type or mutagenized mscS genes and placing a sterile 5 mm 3MM (Whatman) filter paper disk at four equally spaced positions on the surface of the agar. Antibiotic solution (5 µl of a stock solution containing 50 and 25 mg/ml for kanamycin and neomycin, respectively) was added to the disc and the plates incubated at 37°C overnight. The diameter of each clear zone was measured twice at ∼90°, and data from the four replicate discs combined to provide mean diameter and standard deviation. Potassium pools were measured essentially as described previously (Levina et al., 1999) on cells grown to mid-exponential phase (OD650 = 0.5–0.6) in minimal medium containing 1 mM KCl. Cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG for 30 min prior to assay. For the mutant L109S, MJF455 cells were inoculated into minimal medium immediately after transformation with pMscSH6/L109S and, after overnight growth, the cells were diluted into fresh growth medium for the assay of K+ as described above.

Electrophysiology

Patch–clamp recordings (Hamill et al., 1981) were conducted as described previously (Levina et al., 1999). All measurements have been conducted on patches derived from at least two protoplast preparations.

Materials

All media components were obtained from Oxoid, and fine chemicals were from either Sigma-Genosys or Aldrich. Restriction enzymes were purchased from Roche or Promega, and pre-cast Novex SDS–polyacrylamide gels were obtained from Invitrogen-Life Technologies.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Petra Louis, Natalia Levina and Neil Stokes for assistance in the early stages of this project; Paul Blount and Paul Moe for strains and advice on electrophysiology; John Roth, Boris Martinac, Paul Blount and Sergei Sukharev for sharing their unpublished work; Dr Hans de Cock for PhoA antibodies; and Mrs Norma Moore for purifying anti-MscS antibodies. The work is funded by a Wellcome Trust Pro gramme grant (040174), by the EU Fifth Framework programme (W.B.) (Hypersolutes; contract number QLK3-CT-2000-00640) and by a BBSRC Committee Research Studentship (S.S.).

Note added in proof

Since this work was accepted, Bass et al. (Science, 2002, 298, 1582–1587) have described a crystal structure for the open form of MscS. Their data support the conclusions advanced in our paper, in particular, the importance of residues T93, A102 and L109 in TMS3, but they have determined that the protein forms a homoheptamer rather than a hexamer.

References

- Amann E., Ochs,B. and Abel,K.-J. (1988) Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene, 69, 301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schäffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller, W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programmes. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrier C., Coulombe,A., Szabo,I., Zoratti,M. and Ghazi,A. (1992) Gadolinium ion inhibits loss of metabolites induced by osmotic shock and large stretch-activated channels in bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem., 206, 559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P., Sukharev,S.I., Moe,P.C., Schroeder,M.J., Guy,H.R. and Kung,C. (1996a). Membrane topology and multimeric structure of a mechanosensitive channel protein of Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 15, 4798–4805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P., Sukharev,S.I., Schroeder,M.J., Nagle,S.K. and Kung,C. (1996b) Single residue substitutions that change the gating properties of a mechanosensitive channel in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 11652–11657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P., Schroeder,M.J. and Kung,C. (1997) Mutations in a bacterial mechanosensitive channel change the cellular response to osmotic stress. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 32150–32157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P., Sukharev,S.I., Moe,P.C., Martinac,B. and Kung,C. (1999) Mechanosensitive channels in bacteria. Methods Enzymol., 294, 458–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth I.R. and Louis,P. (1999) Managing hypoosmotic stress: aquaporins and mechanosensitive channels in Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Microbiol., 2, 166–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd D., Manoil,C. and Beckwith,J. (1987) Determinants of membrane protein topology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 8525–8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd D., Traxler,B. and Beckwith,J. (1993) Analysis of the topology of a membrane protein by using a minimum number of alkaline phosphatase fusions. J. Bacteriol., 175, 553–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman E. and Beckwith,J. (1975) Analysis of the regulation of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase synthesis using deletions and φ80 transducing phages. J. Mol. Biol., 96, 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang G., Spencer,R.H., Lee,A.T., Barclay,M.T. and Rees,D.C. (1998) Structure of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a gated mechanosensitive ion channel. Science, 282, 2220–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein W. (1986) Osmoregulation by potassium transport in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 39, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein W. and Kim,B.S. (1971) Potassium transport loci in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol., 108, 639–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill O.P., Marty,A., Neher,E., Sakmann,B. and Sigworth,F.J. (1981) Improved patch–clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch., 391, 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Chen,J., Cadene,M., Chait,B.T. and Mackinnon,R. (2002) The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature, 417, 523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M. and von Heijne,G. (1996) Membrane topology of Kch, a putative K+ channel from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 25912–25915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloda A. and Martinac,B. (2001) Structural and functional differences between two homologous mechanosensitive channels of Methanococcus jannaschii. EMBO J., 20, 1888–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y., Shen,Y., Warth,T.E. and Ma,J. (2002) Conformational pathways in the gating of Escherichia coli mechanosensitive channel. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 5999–6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levina N., Tötemeyer,S., Stokes,N.R., Louis,P., Jones,M.A. and Booth,I.R. (1999) Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS and MscL mechanosensitive channels: identification of genes for MscS activity. EMBO J., 18, 1730–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Moe,P.C., Chandrasekaran,S., Booth,I.R. and Blount,P. (2002) Ionic regulation of MscK, a mechanosensitive channel from Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 21, 5323–5330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O.H., Rosebrough,N.J., Farr,A.L. and Randall,R.J. (1951) Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem., 193, 265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoil C. (1992) Analysis of membrane protein topology using alkaline phosphatase and β-galactosidase gene fusions. Methods Cell Biol., 34, 61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinac B., Buechner,M., Delcour,A.H., Adler,J. and Kung,C. (1987) Pressure-sensitive ion channel in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 2297–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaggan D., Jones,M.A., Gouesbet,G., Levina,N., Lindey,S., Epstein,W. and Booth,I.R. (2002) Analysis of the kefA2 mutation suggests that KefA is a cation-specific channel involved in osmotic adaptation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 43, 521–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis S., Inouye,H., Oliver,D. and Beckwith,J. (1983) Mutations that alter the signal sequence of alkaline-phosphatase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 154, 366–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe P.C., Blount,P. and Kung,C. (1998) Functional and structural conservation in the mechanosensitive channel MscL implicates elements crucial for mechanosensation. Mol. Microbiol., 28, 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Byrne C.P. and Booth,I.R. (2002) Osmoregulation and its importance to foodborne microorganisms. Int. J. Food Microbiol., 74, 203–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K., Moe,P.C. and Blount,P. (2002) Functional design of bacterial mechanosensitive channels: comparisons and contrasts illuminated by random mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 27682–27688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou X., Blount,P., Hoffman,R.J. and Kung,C. (1998) One face of a transmembrane helix is crucial in mechanosensitive channel gating. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 11471–11475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivetti C.D., Yen,M-R., Miller,S., Busch,W., Tseng,Y.-H, Booth,I.R. and Saier,M.H. (2003) Two families of prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels. Microbiol. Mol. Rev., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poolman B., Blount,P., Folgering,J.H.A., Friesen,R.H.E., Moe,P.C. and van der Heide,T. (2002) How do membrane proteins sense water stress? Mol. Microbiol., 44, 889–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Sukharev S. (1999) Mechanosensitive channels in bacteria as membrane tension reporters. FASEB J., 13, 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev S. (2002) Purification of the small mechanosensitive channel of E.coli (MscS): the subunit structure, conduction and gating characteristics in liposomes. Biophys. J., 83, 290–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev S.I., Blount,P., Martinac,B., Blattner,F.R. and Kung,C. (1994) A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E.coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature, 368, 265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev S., Betanzos,M., Chiang,C.S. and Guy,H.R. (2001a) The gating mechanism of the large mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nature, 409, 720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev S., Durell,S.R. and Guy,H.R. (2001b) Structural models of the MscL gating mechanism. Biophys. J., 81, 917–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touze T., Gouesbet,G., Boiangiu,C., Jebbar,M., Bonnassie,S. and Blanco,C. (2001) Glycine betaine loses its osmoprotective activity in a bspA strain of Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Microbiol., 42, 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Staehelin,T. and Gordon,J. (1979) Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 76, 4350–4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vonHeijne G. (1992) Membrane protein structure prediction—hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. J. Mol. Biol., 225, 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S.H. and Wimley,W.C. (1999) Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu. Rev. Biophys Biomol. Struct., 28, 319–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]