Abstract

Background

Studies have revealed large variations in average health status across social, economic, and other groups. No study exists on the distribution of the risk of ill-health across individuals, either within groups or across all people in a society, and as such a crucial piece of total health inequality has been overlooked. Some of the reason for this neglect has been that the risk of death, which forms the basis for most measures, is impossible to observe directly and difficult to estimate.

Methods

We develop a measure of total health inequality – encompassing all inequalities among people in a society, including variation between and within groups – by adapting a beta-binomial regression model. We apply it to children under age two in 50 low- and middle-income countries. Our method has been adopted by the World Health Organization and is being implemented in surveys around the world; preliminary estimates have appeared in the World Health Report (2000).

Results

Countries with similar average child mortality differ considerably in total health inequality. Liberia and Mozambique have the largest inequalities in child survival, while Colombia, the Philippines and Kazakhstan have the lowest levels among the countries measured.

Conclusions

Total health inequality estimates should be routinely reported alongside average levels of health in populations and groups, as they reveal important policy-related information not otherwise knowable. This approach enables meaningful comparisons of inequality across countries and future analyses of the determinants of inequality.

Keywords: Health inequality, risk of death, child mortality, extended beta-binomial model

Background

The distribution of health, or health inequality, has become prominent on global policy agendas as researchers have come to regard average health status as an inadequate summary of a country's health performance [1,2]. Almost all health inequality studies have in fact documented differences in average health status across groups of people. Those with an economic focus have measured differences in average health status across income groups [3,4]. Researchers with a sociological focus have examined inequalities in average health status among social classes [5,6]. and those with a political focus have looked at how political structure is related to differences in the average level of health [7]. Other scholars have focused on differences in average health status among racial or ethnic groups or by educational attainment or occupation [8-10]. And most researchers consider differences across political entities such as countries or local governments. Similarly, demographers have also long studied differences in average health status, particularly in children, across age, sex, education and racial groups [11-13]. In low- and middle-income countries there exists a rich demographic literature on levels and trends in child mortality and causes associated with them [14-16].

In this paper, we define the concept of total health inequality, and demonstrate how to measure it by the variation in health status across individuals (within a country as a whole or any subgroup within a country). This approach complements the existing group-level approaches, a fact that can even be demonstrated mathematically. That is, the standard analysis of variance identity applies to variations in health status just as it does to all other coherent variables:

"Total" = "Between Group" + "Within Group"

Existing literature has focused exclusively on the "between group" component. In this paper, the missing "within-group" component is added to the existing measures to arrive at total health inequality. With total health inequality, no individual variation in health status is ignored. With this measure added to existing reporting standards, public health policy can be targeted at reducing inequalities across individuals, in addition to its existing goal of reducing disparities in average health status across countries and groups in society.

We would like to emphasize that total health inequality complements group level measures; it does not replace them. After all, if average health attainment is the same across a given set of groups, total health inequality could still be unacceptably high (because of intra-group variation across individuals), whereas if total health inequality is small, then the differences among any set of groups, albeit potentially systematic, must also be small. In our view, between, within, and total levels of health inequality should be reported henceforth.

Preferably, measures of inequality in healthy life expectancy (the number of years in full health an individual born today can expect to live [17]) would be computed, but this paper focuses on a preliminary step for which data are more readily available – developing methods for the measurement of total inequality in the probability of child survival. Survival from birth to two years of age is only one aspect of health, but it is a useful place to start since it is a critical part of health status, particularly in developing countries [4,18].

The normative principles involved in choosing a measure of inequality are discussed briefly. Instead of making an arbitrary choice, the inequality measure selected is consistent with the results of a survey of normative preferences of over 1000 health professionals conducted by WHO and used in the World Health Report 2000 [19]. Comparisons with applications of other popular measures of income inequality to health are also presented.

Methods

The data analyzed are from 50 countries where a Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) had been conducted and the data were available. Table 1 lists the countries, sample size and year of the surveys used. The DHS is a 20-year project conducting high quality national sample surveys on population and maternal and child health. Funded primarily by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), DHS is administered by Macro International Inc. [20]. Low-income country governments and international organizations have long relied on DHS data to monitor a variety of child and maternal health and family planning indicators [21]. One of the most significant contributions of the DHS is the collection of internationally comparable data on the demographic and health characteristics of populations in developing countries [22-25]..

Table 1.

DHS survey year and sample size

| Country | Year | No. of households interviewed |

| Bangladesh | 1997 | 9,127 |

| Benin | 1996 | 5,491 |

| Bolivia | 1994 | 8,603 |

| Brazil | 1996 | 12,612 |

| Burkina Faso | 1993 | 6,354 |

| Burundi | 1987 | 3,970 |

| Cameroon | 1997 | 5,501 |

| Central African Republic | 1995 | 5,884 |

| Colombia | 1995 | 11,140 |

| Comoros | 1996 | 3,050 |

| Cote d'Ivoire | 1994 | 8,099 |

| Dominican Republic | 1996 | 8,422 |

| Ecuador | 1987 | 4,713 |

| Egypt | 1995 | 14,779 |

| Ghana | 1994 | 4,562 |

| Guatemala | 1995 | 12,403 |

| Haiti | 1995 | 5,356 |

| India | 1993 | 89,777 |

| Indonesia | 1994 | 28,168 |

| Kazakhstan | 1995 | 3,771 |

| Kenya | 1993 | 7,540 |

| Liberia | 1986 | 5,239 |

| Madagascar | 1997 | 7,060 |

| Malawi | 1992 | 4,849 |

| Mali | 1996 | 9,704 |

| Mexico | 1987 | 9,310 |

| Morocco | 1992 | 9,256 |

| Mozambique | 1997 | 8,779 |

| Namibia | 1992 | 5,421 |

| Nepal | 1996 | 8,429 |

| Nicaragua | 1998 | 13,634 |

| Niger | 1995 | 7,577 |

| Nigeria | 1990 | 8,781 |

| Pakistan | 1991 | 6,611 |

| Paraguay | 1990 | 5,827 |

| Peru | 1996 | 28,951 |

| Philippines | 1998 | 13,983 |

| Rwanda | 1992 | 6,551 |

| Senegal | 1997 | 8,593 |

| Sudan | 1990 | 5,860 |

| Thailand | 1987 | 6,775 |

| Togo | 1998 | 8,569 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1987 | 3,806 |

| Tunisia | 1988 | 4,184 |

| Uganda | 1995 | 7,070 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 1996 | 8,120 |

| Uzbekistan | 1996 | 4,415 |

| Yemen | 1992 | 6,010 |

| Zambia | 1996 | 8,021 |

| Zimbabwe | 1994 | 6,128 |

The DHS are conducted through in-person interviews. The samples, which are all above 3,000 households in the countries analyzed in this study, are the result of a multi-stage stratified sampling design [26]. The DHS sampling weights are used to produce nationally representative estimates.

For each country we used the latest year of available data from a nationally representative DHS, ranging from 1987 to 1997. For each mother surveyed the number of children born and the number survived to age 2 was calculated. A ten-year observation period was used ending two years prior to the interview year, to avoid censoring effects. This period is a compromise between providing recent estimates and ensuring enough births to reduce the effects of sampling error. Measuring survival to (or death by) age 5, would involve a longer censoring period, produce older estimates of inequality, and not differ much from the under 2 mortality because on average, 80% of under 5 deaths occur in the first two years of life [26,27].

To provide a partial but independent validation of the DHS-based results, mortality data by municipality in Mexico [28] and Brazil [29] from different data sources were analyzed. Data on socioeconomic variables [30] and on the political system [31] of each country were also collected to help us explore possible causes of differences in inequality. The socioeconomic variables were collected for the year the survey was conducted in each country.

The population of interest includes all children born alive in a country in a given time period. Ideally, one would measure the length of time each child is expected to live from birth to two years and then use a measure of inequality to summarize the distribution of these survival expectations. Making the inference from the dichotomous data on child survival to health inequality requires several methodological steps.

The first step is to estimate the distribution of the probability of death across children in each national sample. The chief methodological difficulty here is that for any one child, only the dichotomous variable of survival to two years is measured, while the probability of dying for each child is not observed. These probabilities are estimated using the extended beta-binomial model [32-34]. This model has been widely applied in biomedical research, most commonly for modeling animal littermate survival probabilities, and in political science to model voting statistics [32,34-38]. In this application, we model the number of child deaths within a family with a binomial distribution with equal risk of dying per child, and then allow the risks to vary across families according to a beta distribution [35]. (See Additional file 1 for more details on the specification of the model.)

Potential confounders, including mother's age, number of children, level of education, and average birth interval, were controlled for [13]. This procedure relaxes the assumptions of the model, making it more flexible. However, the basic model fits the data well, and controlling for these variables does not materially affect the estimates of health inequality. When the covariates have no effect, the beta distributed random effect portion of the model ensures that the level of variability is not underestimated.

For Mexico and Brazil, the extended beta-binomial model was also applied to the municipality-level mortality data sets to validate the model. The underlying assumption is that small geographical areas (which are treated analogously to families) include mostly homogeneous populations for which the risk of death is similar. In both countries, the estimates of inequality from the extended beta-binomial model did not materially differ between the two data sets used.

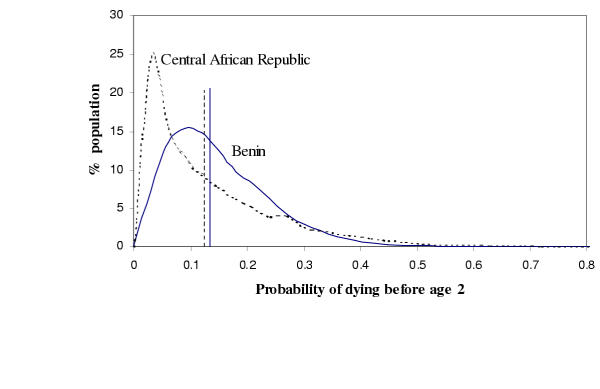

As an example of the results of the survey analysis, Figure 1 shows the estimated distribution of the probability of dying before age 2 in Benin and the Central African Republic, and the corresponding distributions of expected childhood survival time (up to two years) for those countries. These two countries were chosen because they have very similar average probabilities of death (0.13 and 0.12, respectively), and therefore very similar mean survival times (1.86 and 1.87 years, respectively), but markedly different distributions of actual survival time around these means and hence divergent levels of health inequality. For example, in the Central African Republic, about 25% of children born have a probability of death lower than three percent. In contrast, children in Benin have risks of death more closely distributed around its mean, with only 4% of its children having a probability of death lower than three percent. Clearly at the lower end of the distributions, Benin does worse, but it does much better at the higher extreme. For example, in Benin less than 1% of children born have a probability of death greater than forty percent, contrasted with the Central African Republic, where more than 4% of children have that probability of death. This is merely one striking example of why summarizing health status with only mean levels is misleading.

Figure 1.

Distribution of probability of death between birth and age two (2q0), for Benin (solid line) and the Central African Republic (dashed line). The curves are density estimates and the vertical lines are the average 2q0 for each country.

The second step is to transform the estimated probability of death between birth and age two for each child (2q0 in demographic notation) to the expected survival time in the first two years of life, S. Although the results do not change materially, we opted to measure inequality in survival time, instead of probability of survival, as it is analogous to inequality in health expectancy and is more interpretable. Expected survival time can be calculated as

![]()

where S is expected survival time, and 2m0 is the mortality rate in the first two years of life [39]. 2m0 can, in turn, be calculated from the probability of dying in the first two years of life,  [39].

[39].

Finally, since printing fifty plots like Figure 1 would be unwieldy, we give numerical summaries of health inequality. To do this, several normative criteria have to be addressed. At least three general normative dimensions are relevant [17]. First, measures of inequality range from absolute to relative. Absolute measures are independent of mean survival time, whereas relative measures adjust for the mean. If one believes that more variation in health states is acceptable when average survival time is higher, then a measure close to the relative end of the continuum would reflect that choice; on the other hand, if one believes that a given discrepancy in expected survival across people should be considered in the same way, irrespective of the mean survival time in that population, then an absolute measure of inequality would be appropriate. The second normative dimension is the weight given to outliers. One might believe that the majority of children is what measures should be based on, or one might instead want to focus primarily on the worst and best off. The final dimension is whether individuals should be compared to the average of their communities or to each of the individuals within their communities separately.

A range of measures of inequality that reflect many different normative positions were developed, including measures used in quantifying income inequality (such as the Gini index), variance measures, and many that have not been previously considered [17]. Although it need not have turned out this way, in the present analysis these measures all gave substantively consistent empirical results. For empirical analyses, the inequality index (II) used was derived from a survey of the normative preferences of over 1,000 health professionals and other individuals with an interest in health systems [19]. The index is defined as

![]()

where si is the expected survival time between birth and age two of individual i, and s is the average expected survival time in the first two years of life in the population. This index of inequality (II) is logically between a relative and an absolute measure, so the average survival time is included in the denominator. The index is based on comparing each child with every other child in the population (thus the sum of the differences in the numerator), and gives a large weight to the best and worst off (the differences are raised to the power of three). Larger values of II indicate more individual level inequality in child survival. The health inequality point estimates and uncertainty bounds are mean posterior estimates and 95% credible intervals, respectively, computed from the extended beta-binomial model with flat priors and the traditionally used asymptotic normal approximations (e.g. [40]).

Results

Table 2 lists estimates of child survival inequality using II for each of 50 countries, ranked from most unequal (Liberia) to least unequal (Colombia). For comparison, estimates of child survival inequality were calculated for three other commonly used summary measures of distributions – the variance, the Gini index, and the coefficient of variation. The pairwise rank order correlations between the four measures were all higher than 0.93. Table 3 presents the ranking of countries from most to least unequal by the four measures of inequality used in this analysis.

Table 2.

Child survival inequality index for 50 countries, estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

| Country | Inequality Index | 95% CI | Country | Inequality Index | 95% CI |

| Liberia | .75 | .56 – .91 | Comoros | .36 | .17 – .53 |

| Mozambique | .73 | .59 – .87 | Egypt | .35 | .29 – .42 |

| Central African Republic | .69 | .53 – .85 | Uganda | .34 | .23 – .48 |

| Nigeria | .66 | .55 – .77 | Burkina Faso | .34 | .21 – .47 |

| Malawi | .62 | .44 – .78 | Kenya | .34 | .24 – .44 |

| Rwanda | .56 | .43 – .68 | Ecuador | .32 | .18 – .44 |

| Niger | .54 | .42 – .66 | Benin | .31 | .19 – .45 |

| Pakistan | .54 | .43 – .64 | Bangladesh | .30 | .20 – .41 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | .52 | .40 – .64 | Bolivia | .27 | .17 – .37 |

| Mali | .51 | .41 – .60 | Tunisia | .25 | .14 – .35 |

| Namibia | .47 | .31 – .61 | Morocco | .25 | .15 – .34 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | .47 | .35 – .59 | Brazil | .23 | .14 – .33 |

| Togo | .46 | .35 – .57 | Guatemala | .23 | .16 – .30 |

| Zambia | .46 | .32 – .59 | Senegal | .22 | .14 – .32 |

| Madagascar | .45 | .33 – .58 | Peru | .22 | .17 – .26 |

| Yemen | .44 | .34 – .53 | Zimbabwe | .21 | .11 – .31 |

| Nepal | .41 | .29 – .52 | Dominican Republic | .21 | .11 – .30 |

| Cameroon | .40 | .25 – .54 | Nicaragua | .20 | .13 – .27 |

| Sudan | .40 | .29 – .51 | Trinidad and Tobago | .15 | .04 – .25 |

| Burundi | .40 | .24 – .55 | Thailand | .15 | .05 – .24 |

| Indonesia | .40 | .34 – .45 | Mexico | .14 | .06 – .21 |

| India | .39 | .36 – .43 | Paraguay | .12 | .05 – .20 |

| Haiti | .39 | .22 – .55 | Kazakhstan | .11 | .01 – .21 |

| Ghana | .39 | .23 – .53 | Philippines | .10 | .05 – .16 |

| Uzbekistan | .36 | .21 – .52 | Colombia | .08 | .03 – .15 |

Table 3.

Relative ranks of child survival inequality by four measures of inequality. Rank 1 refers to the most unequal.

| Country | II | Std. deviation | Coefficient of variation | Gini coefficient |

| Liberia | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Mozambique | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Central African Republic | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Nigeria | 4 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

| Malawi | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Rwanda | 6 | 6 | 8 | 9 |

| Nigeria | 7 | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| Pakistan | 8 | 7 | 13 | 17 |

| Cote d'ivoire | 9 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Mali | 10 | 10 | 6 | 5 |

| Namibia | 11 | 14 | 22 | 26 |

| Tanzania | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 |

| Togo | 13 | 12 | 16 | 18 |

| Zambia | 14 | 13 | 9 | 8 |

| Madagascar | 15 | 15 | 11 | 11 |

| Yemen | 16 | 16 | 14 | 13 |

| Nepal | 17 | 17 | 15 | 14 |

| Cameroon | 18 | 19 | 23 | 23 |

| Sudan | 19 | 18 | 20 | 21 |

| Burundi | 20 | 20 | 17 | 15 |

| Indonesia | 21 | 24 | 30 | 31 |

| India | 22 | 21 | 26 | 25 |

| Haiti | 23 | 22 | 19 | 19 |

| Ghana | 24 | 23 | 25 | 24 |

| Uzbekistan | 25 | 30 | 35 | 39 |

| Comoros | 26 | 25 | 27 | 27 |

| Egypt | 27 | 26 | 28 | 29 |

| Uganda | 28 | 27 | 24 | 22 |

| Burkina Faso | 29 | 28 | 18 | 16 |

| Kenya | 30 | 29 | 32 | 32 |

| Ecuador | 31 | 32 | 33 | 33 |

| Benin | 32 | 31 | 21 | 20 |

| Bangladesh | 33 | 33 | 29 | 28 |

| Bolivia | 34 | 34 | 31 | 30 |

| Tunisia | 35 | 36 | 38 | 37 |

| Morocco | 36 | 35 | 36 | 35 |

| Brazil | 37 | 39 | 40 | 40 |

| Guatemala | 38 | 37 | 37 | 36 |

| Senegal | 39 | 38 | 34 | 34 |

| Peru | 40 | 40 | 39 | 38 |

| Zimbabwe | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 |

| Dominican Republic | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 |

| Nicaragua | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 |

| Trinidad & Tobago | 44 | 46 | 47 | 48 |

| Thailand | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Mexico | 46 | 44 | 44 | 44 |

| Paraguay | 47 | 47 | 46 | 46 |

| Kazakhstan | 48 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Philippines | 49 | 48 | 48 | 47 |

| Colombia | 50 | 49 | 49 | 49 |

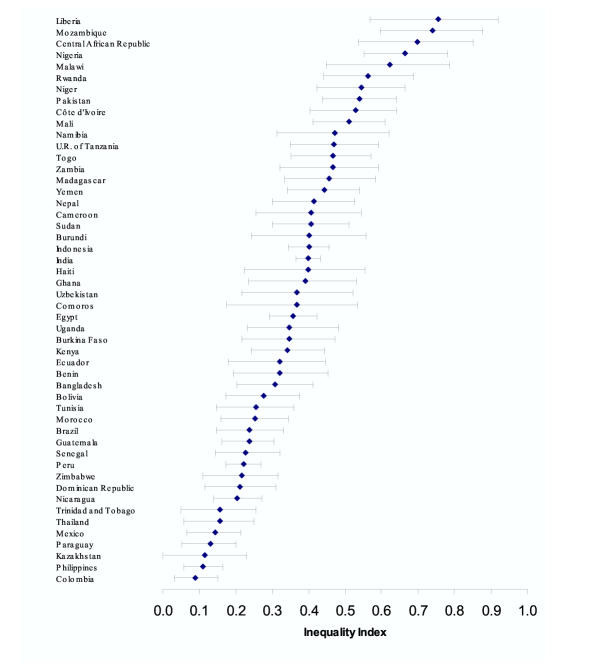

To get a sense of the uncertainty in estimation, Figure 2 plots the inequality estimates with 95% confidence intervals for each country (the size of the confidence intervals is mostly a function of the sample size in each country). These kinds of basic data could be used by health professionals to base further research, particularly into the determinants of total health inequality, and eventually public policy to reduce inequalities.

Figure 2.

Child survival inequality index and 95% confidence intervals for 50 countries.

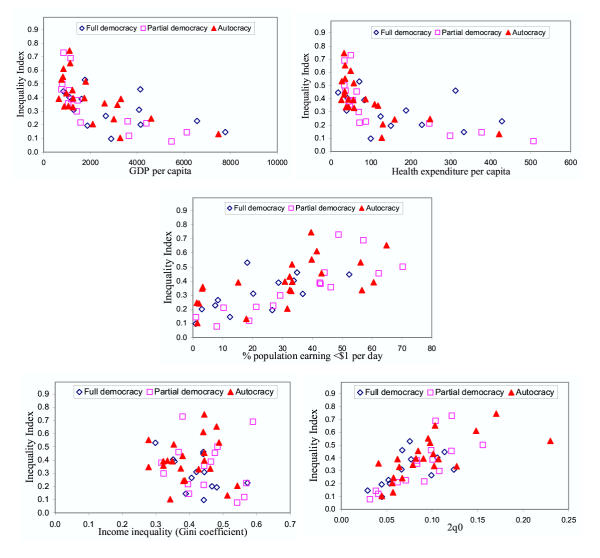

Figure 3 presents an exploratory view of the relationship between our measure of health inequality and five plausible explanatory variables, interacted with the type of government. The purpose of these graphs is to understand the measure of inequality developed and to explore correlations with other relevant variables. Determining what causes changes in inequality is a critical issue but one that we do not pursue in any detail here. Among the variables included, GDP per capita and health expenditures per capita are negatively correlated with health inequality, which lends face validity to the inequality measure. As with average level of mortality, the relationship between health inequality and GDP per capita and health expenditure per capita is very strong at low levels of income and expenditure, and the effect is smaller at higher levels. The relationship between health inequality and absolute poverty (defined as the percent of the population earning less than one international dollar per day) appears to be more linear, with considerable variation in inequality at each given level of poverty. More surprisingly, health inequality seems entirely uncorrelated with income inequality (r = -0.16), as measured by economists' most commonly used measure, the Gini index calculated for income.

Figure 3.

Child survival inequality index, plotted against five economic and demographic indicators by type of government.

Additionally, inequality in childhood survival is positively related to the mean probability of death (2q0), but at a given level of mortality there is significant variation in inequality. This confirms the expected relationship and also reflects the fact that traditionally reported measures of average levels of health are insufficient for summarizing the health experience of a population. Finally, each point in each graph also codes the type of political system. The graphs seem to indicate that full democracies (represented as diamonds) tend to have lower values of inequality than partial democracies (squares) or autocracies (triangles), as would be expected. (Partial democracies include countries that have adopted some democratic practices, such as popular elections to legislatures with limited powers, but most have not completed the transition from autocratic practices.) However, and perhaps surprisingly, health inequality is otherwise unrelated to the type of political system either directly or in interaction with any of the five potential explanatory variables.

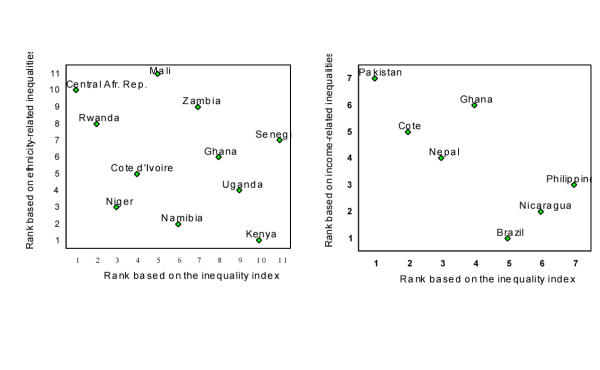

The individual-level approach to conceptualizing and measuring health inequality appears to complement the group-level approaches. To show that the total health inequality measures offered here are at least sometimes distinct from group-level analyses, the results of the present analysis are compared to those of Wagstaff [4] and Brockerhoff and Hewett [16]. Wagstaff calculated inequalities among income groups in 7 countries, measured by a concentration index. Brockerhoff and Hewett measured ethnic differences in 11 countries via odds ratios. Brockerhoff and Hewett used subsets of the same DHS datasets as used in this analysis, while Wagstaff used mostly data from the Living Standards Measurement Surveys.

Figure 4 plots of the ranks of the total health inequality measure (II) by each of these group-level measures (with rank 1 assigned to the country with the largest inequalities). Clearly the individual-level measure is tapping into different concepts as the two pairs are not even positively correlated. For example, the Central African Republic and Rwanda have large individual-level inequalities in child survival, but relatively smaller inter-ethnic group inequalities. (These results do not contradict, but rather imply that there is considerable intra-ethnic group inequality that is, by definition, not picked up by the group-level measures.) In contrast, Kenya has less individual-level health inequality relative to other sub-Saharan African countries, but more ethnicity-related inequalities. Similarly, Brazil and Nicaragua have large differences in child mortality levels across income groups, but less individual-level inequality than Pakistan and Cote d'Ivoire. These different results establish that measures of total health inequality are indeed measuring different concepts and uncovering different findings than the existing group-level approaches.

Figure 4.

Country rankings of child survival inequality: comparing the individual-level inequality index with existing indices of income- and ethnicity-related inequalities in child survival. A rank of 1 on all scales indicates the highest levels of inequality.

Conclusions

This paper presents the first measures of total health inequality of a population. Such measures could serve as an important complement to existing group-level approaches in the literature on health inequalities among groups. Including individual-level variation, as done here, produces estimates of inequality that capture the entire distribution of risk of death in the population and that are directly comparable across countries.

At the same average level of health status, countries can achieve widely varying levels of health inequality. Since measuring and communicating this type of information seems essential to making informed public policy, we believe inequality should be measured and reported together with average levels of health status.

Estimating the underlying distribution of risk is useful for understanding the nature and possibly the causes of health inequality using observed dichotomous outcomes such as survival and death. This or a related approach should prove useful for examining the risk of ill-health for all age groups, such as in measures of inequality in health expectancy.

Considerable future research needs to be conducted into health inequality. For one area, efforts should continue to measure inequalities in child survival outside of the fifty countries analyzed here. For another, the normative underpinnings of popular measures of health inequality should be further clarified. Similarly, other measures that formalize richer normative principles should be developed. Further efforts need to be made to measure what types of people, policymakers, and democratic electorates prefer one normative position rather than another. Third, new databases need to be created and statistical methods developed that enable researchers to expand measures of inequality in child survival in the first two years of life to inequality in health expectancy in general. Fourth, we should seek further external validation of these results, along the lines of the vital registration-based analysis conducted for Mexico and Brazil. Finally, and most importantly for influencing health policy globally, scholars should pursue an understanding of the determinants of inequality. We need to understand not only how average levels of health status of populations can be raised but also how health inequalities can be reduced.

There are several limitations to this study. The ranking of countries is influenced by the year the data were collected and particularly for those most affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the estimate of the inequality index might change if more recent data were available. Since women of reproductive age are the basic sampling units in these surveys, their premature death (from maternal or other causes) excludes their children from the studies. Such children often have an elevated mortality risk and their exclusion may bias estimates child mortality (both level and inequality) downward. This bias is likely to be greater in countries with higher maternal mortality and HIV/AIDS epidemics. Our preliminary explorations of this issue indicate that the estimate of the inequality index changes very little, and not enough to result in a change of rankings across countries.

Some of the potential implications of this article include a research program devoted to developing and improving measures of health inequality, a substantial change in data collection efforts by public health authorities internationally, and even ongoing changes in national and international public policy as a result. All this possible activity takes nothing away from the important existing focus on differences in average health levels across groups, but measuring and reporting individual health inequality adds an important new perspective as well.

Competing interests

None declared

Authors' contributions

EG and GK participated in the design of the study, the interpretation of the findings and the write-up of the manuscript. EG performed the statistical analysis. Both authors wrote, read, and approved the final manuscript.

List of abbreviations

DHS: Demographic and Health Surveys

II: Inequality index

WHO: World Health Organization

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Christopher Murray, Julio Frenk, Alan Lopez, Brad Palmquist, Joshua Salomon, Lana Tomaskovic, and Brodie Ferguson for valuable comments. Our thanks go to the World Health Organization, the U.S. National Science Foundation (SBR-9729884) and the National Institutes on Aging (PO1 AG17625-01) for research support.

A file with all data and information necessary to replicate the results in this paper is available from the authors

Contributor Information

Emmanuela Gakidou, Email: gakidoue@who.int.

Gary King, Email: king@harvard.edu.

References

- World Health Organization Health Systems: improving performance. World Health Report 2000. Geneva, Switzerland. 2000.

- Acheson D. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health. 1998 London, UK, The Stationery Office. 1998.

- World Bank Country Reports on Health, Nutrition, Population, and Poverty. Washington, DC, USA. 2002. http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/health/data/intro.htm

- Wagstaff A. Socioeconomic inequalities in child mortality: comparisons across nine developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:19–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, Patel C, North F, Head J, White I, Brunner E, Feeney A. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study [see comments]. Lancet. 1991;337:1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Marshall S, Pearce N. Social class inequalities in the decline of coronary heart disease among New Zealand men, 1975–1977 to 1985–1987. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:393–398. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro V. Health and equity in the world in the era of "globalization". Int J Health Serv. 1999;29:215–225. doi: 10.2190/MQPT-RLTH-KUPJ-2FQP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst AE, Geurts JJ, van den Berg J. International variation in socioeconomic inequalities in self reported health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:117–123. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.2.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst AE, Groenhof F, Mackenbach JP, Health EW. Occupational class and cause specific mortality in middle aged men in 11 European countries: comparison of population based studies. EU Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health [see comments]. BMJ. 1998;316:1636–1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7145.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:757–771. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston SH, Haines MR. Fatal years: child mortality in late nineteenth-century America. Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press. 1991;266 [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC, McDonald P. Influence of maternal education on infant and child mortality: levels and causes. International Population Conference, Manila. 1981;2:79–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-2281(82)90012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicego G, Ahmad O. Infant and Child Mortality #20. Calverton, Macro International, Inc. 1996.

- Hill K, Pande R, Mahy M, Jones G. Trends in child mortality in the developing world: 1960 to 1996. New York, NY: UNICEF. 1999.

- Hill K, Pande R. The recent evolution of child mortality in the developing world. Arlington, VA, Partnership for Child Health Care, Basic Support for Institutionalizing Child Survival [BASICS] Current Issues in Child Survival Series. 1997.

- Brockerhoff M, Hewett P. Inequality of child mortality among ethnic groups in sub-Saharan Africa. [Review] [36 refs]. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:30–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakidou E, Murray CJL, Frenk J. Defining and measuring health inequality: an approach based on the distribution of health expectancy. Bulletin of WHO. 2000;78:42–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaba B, David P. Fertility and the distribution of child mortality risk among women: an illustrative analysis. Popul Stud. 1996;50:263–278. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000149346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gakidou E, Murray CJL, Frenk J. Measuring preferences for health systems performance assessment. GPE Discussion Paper 20 2000 Geneva, World Health Organization. 2000.

- USAID & Macro International Demographic and Health Surveys. 1984. http://www.measuredhs.com

- Stanton C, Abderrahim N, Hill K. An assessment of DHS maternal mortality indicators. Studies in Family Planning. 2000;31:111–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan J, Rutstein S, Bicego G. Infant and Child Mortality #15. Calverton, Macro International, Inc. 1994.

- Curtis SL. Assessment of the quality of data used for direct estimation of infant and child mortality in DHS-II surveys. Calverton, Maryland, Macro International Demographic and Health Surveys. 1995.

- Boerma JT, Sommerfelt AE. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS): contributions and limitations. World Health Statistics Quarterly. 1993;46:222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Pande R, Mahy M, Jones G. Trends in child mortality in the developing world: 1960–1996. New York: UNICEF; 1999.

- Rutstein S. Factors associated with trends in infant and child mortality in developing countries during the 1990s. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1256–1270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macro International Inc. An assessment of the quality of health data in DHS surveys #2. Calverton, Maryland, Macro International Inc. 1993.

- Fundacion Mexicana para la Salud, Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Deaths and population by municipality in Mexico. 1998.

- Instituto Brasilero de Geografía e Estadística (IBGE). Sistema de Informacao sobre Mortalidade. 1994. http://www.datasus.gov.br, http://www.ibge.gov.br.

- World Health Organization GPE Socio-economic database. WHO. 2000.

- Gurr TR, Jaggers K. Polity III: Regime Change and Political Authority, 1800–1994. Computer file, Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI. 1996.

- Prentice RL. Binary regression using an extended beta-binomial distribution, with discussion of correlation induced by covariate measurement errors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1986;81:321–327. [Google Scholar]

- King G. Unifying political methodology: the likelihood theory of statistical inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1989.

- Palmquist B. Analysis of proportions data. College Station, Texas.

- Brooks SP, Morgan BJ, Ridout MS, Pack SE. Finite mixture models for proportions. Biometrics. 1997;53:1097–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto E, Yanagimoto T. Statistical methods for the beta-binomial model in teratology. Environmental Health Perspective. 1994;102S:25–31. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, McCullagh P. Case studies in binary dispersion. Biometrics. 1993;49:623–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths D. Maximum likelihood estimation for the beta-binomial distribution application to the household distribution of the total number of cases of a disease. Biometrics. 1973;29:637–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston SH, Keyfitz N, Schoen R. Causes of death: Life tables for national populations. New York and London: Seminar Press. 1972.

- King G, Tomz M, Wittenberg J. Making the most of statistical analyses: improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science. 2000;44:341–355. [Google Scholar]