Summary

The mammalian lens consists of an aged core of quiescent cells enveloped by a layer of synthetically active cells. Abundant gap junctions within and between these cell populations ensure that the lens functions as an electrical syncytium and facilitates the exchange of small molecules between surface and core cells. In the present study, we utilized an in vivo mouse model to characterize the properties of an additional pathway, permeable to macromolecules, which co-exists with gap-junction-mediated communication in the lens core. The TgN(GFPU)5Nagy strain of mice carries a green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene. In the lenses of hemizyous animals, GFP was expressed in a variegated fashion, allowing diffusion of GFP to be visualized directly. Early in development, GFP expression in scattered fiber cells resulted in a checkerboard fluorescence pattern in the lens. However, at E15 and later, the centrally located fiber cells became uniformly fluorescent. In the adult lens, a superficial layer of cells, approximately 100 μm thick, retained the original mosaic fluorescence pattern, but the remainder, and majority, of the tissue was uniformly fluorescent. We reasoned that at the border between the two distinct labeling patterns, a macromolecule-permeable intercellular pathway was established. To test this hypothesis, we microinjected 10 kDa fluorescent dextran into individual fiber cells and followed its diffusion by time-lapse microscopy. Injections at depths of >100 μm resulted in intercellular diffusion of dextran from injected cells. By contrast, when injections were made into superficial fiber cells, the injected cell invariably retained the dextran. Together, these data suggest that, in addition to being coupled by gap junctions, cells in the lens core are interconnected by a macromolecule-permeable pathway. At all ages examined, a significant proportion of the nucleated fiber cell population of the lens was located within this region of the lens.

Keywords: Lens, Syncytium, Cell-cell communication, Tissue mosaicism, Green fluorescent protein

Introduction

The ocular lens is composed of epithelial cells, which form a monolayer across the anterior surface of the tissue, and fiber cells, which constitute the remainder and majority of the tissue volume. Fiber cells are formed continuously throughout life by the differentiation of epithelial cells near the lens equator. Fiber cell differentiation involves withdrawal from the cell cycle, an enormous increase in cell length and specialization for the synthesis of crystallin proteins (Piatigorsky, 1981). A late stage in fiber differentiation is the breakdown of nuclei and other cytoplasmic organelles (Bassnett, 2002). This is thought to eliminate potential light-scattering structures from the optical axis. In the adult lens, the nucleated fiber cells are located in a thin layer at the periphery.

Lens growth occurs by the addition of fiber cells to the surface of the tissue. With time, newly differentiated fiber cells bury mature elongated fibers, effectively isolating them from the humors of the eye. There is no cell turnover and, consequently, fibers at all stages of differentiation are continually present. Those cells that differentiated first are located nearest the center of the tissue, whereas the most recently formed cells are found at the surface.

For optical reasons, fiber cells in the lens are tightly packed, and the space between them is narrow and tortuous (Paterson, 1970; Rae, 1979). Consequently, it is believed that the inner fiber cells do not obtain nutrients directly from the surrounding ocular humors via a paracellular pathway (Kaiser and Maurice, 1964). Rather, small molecules are thought to enter the surface cells and diffuse from cell to cell into the core of the lens. This view of the lens, in which the metabolism of the mature lens fibers is sustained via communication with cells at the periphery, has been termed ‘metabolic cooperation’ (Goodenough et al., 1980).

The electrical resistance between individual fiber cells in the lens is lower than expected for cells separated by intact plasma membranes (Duncan, 1969). This observation was originally interpreted as indicating that cell membranes degenerate during fiber differentiation. However, in subsequent studies, it became apparent that the lens is richly endowed with gap junctions (Benedetti et al., 1976; Goodenough, 1992; Gruijters et al., 1987; Nonaka et al., 1976). Gap junctions are composed of connexin proteins, and in the lens, three connexin isoforms (α1, α3 and α8) are expressed (Goodenough, 1992). Expression of α1 connexin is restricted to the lens epithelium. The fiber cells express α3 and α8 isoforms, although the latter may also be present at low levels in the epithelium (Dahm et al., 1999). Gap junction channels allow the regulated passage of small (<1200 Da) molecules directly from cell to cell, thus providing a route for the exchange of ions and small metabolites (Simpson et al., 1977). Connexins are abundant integral components of the fiber cell plasma membrane and, in some species, connexin plaques can account for more than 50% of the membrane surface (Kuszak et al., 1978). The central role played by gap-junction-mediated cell-cell communication in lens physiology was underscored by the discovery that mutations in fiber cell connexins can lead to cataracts. Mutations in α8 result in dominant cataracts in mice (Chang et al., 2002; Graw et al., 2001; Steele et al., 1998) and humans (Berry et al., 1999; Pal et al., 2000), and α3 mutations cause autosomal dominant congenital human cataract (Mackay et al., 1999; Rees et al., 2000). Similarly, targeted deletion of α3 or α8 in mice leads to electrical uncoupling of fiber cells and opacification of the tissue (Baldo et al., 2001; Gong et al., 1997; Gong et al., 1998; White et al., 1998).

Although there is compelling biochemical and ultrastructural evidence that gap junctions link adjacent fiber cells in the lens, a recent report suggested the co-existence of a parallel pathway. Shestopalov and Bassnett microinjected a plasmid encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) into the lenses of embryonic chickens in ovo (Shestopalov and Bassnett, 2000). When expressed in individual fiber cells in the center of the lens, GFP diffused into adjacent cells. Conversely, GFP did not diffuse from cell to cell when expressed in cells located at the periphery of the same lens. The molecular weight (27 kDa) of the marker implied that GFP molecules diffused via a novel intercellular route. This pathway was distinct from gap junctions in that it was permeable to proteins and other macromolecules. Furthermore, it coupled only mature fibers in the lens, as opposed to gap junctions, which are present across the tissue (Benedetti et al., 1974). In the current study, we used a novel genetic approach to examine the exchange of macromolecules between cells in the mammalian lens. Our data suggest that the diffusion of macromolecules between fiber cells in the lens core may be a universal feature of the vertebrate lens.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The transgenic mouse strain used in this study (TgN(GFPU)5Nagy) was generated originally in the laboratory of Andras Nagy (Hadjantonakis et al., 1998). In this strain, the gene encoding GFP is controlled by a hybrid CAG promoter (Miyazaki et al., 1989), which drives high-level ubiquitous expression in the mouse. We obtained TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mice on a C57BL/6 genetic background from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME).

Animals (E13-adults) were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and decapitation according to a protocol approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee. Lenses were removed through an incision in the posterior globe. To avoid cold cataract formation, lenses were dissected in prewarmed media.

Microinjection

Lenses were immobilized in 1.5% low melting point agarose dissolved in minimum essential medium (MEM). Microinjections were made through the posterior capsule. Injection pipettes were pulled from 1.2 mm O.D. thin wall borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL), using a horizontal pipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Pipette tips had an average diameter of 1–2 μm. Dye solution was introduced into the tip of the injection pipette and overlaid with 0.6 M LiCl. Lens fiber cells were microinjected iontophoretically with 10 mg/ml solution of 10 kDa tetramethylrhodamine dextran (TMRD, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Dye was injected for 30 seconds at 0.5 μA using a dual current generator (Model 260, World Precision Instruments). Four or five injections were made into each lens. Injections were made at various depths, beginning at the surface and moving in 50 μm increments towards the center of the tissue. Lenses were examined by confocal microscopy immediately following injection and at various intervals thereafter.

Microscopy

Confocal microscopy was used to evaluate the distribution of GFP, AQP0, actin or TMRD within the lens. Intact lenses and vibratome slices of the lens were utilized. Intact lenses were maintained in MEM at 37°C on the stage of the confocal microscope using an air curtain device (Air Therm, World Precision Instruments). Lens slices were prepared as previously described (Shestopalov and Bassnett, 2000). The confocal microscope (LSM410, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) was equipped with an argon/krypton laser. GFP fluorescence was visualized using 488 nm excitation and a 515–565 nm bandpass emission filter. TMRD and Alexa-568 conjugates (Molecular Probes) were visualized using 568 nm excitation and a 590 nm longpass emission filter. For three-dimensional reconstructions of GFP fluorescence, stacks of optical sections were collected using a 40 × 1.2 N.A. planapochromat water immersion lens (Zeiss). Volume rendering was performed using Voxblast software (Version 3.0; Vaytek, Fairfield, IA) as described previously (Shestopalov and Bassnett, 2000). In some experiments, samples were counterstained to visualize the distribution of filamentous actin or cell nuclei. To visualize actin, fixed and permeabilized lens slices were incubated with phalloidin-Alexa 568 (Molecular Probes) as described previously (Bassnett et al., 1999). To stain nuclei, fixed and permeabilized lens slices were preincubated in 100 μg/ml DNase-free RNase A in 2×SSC for 30 minutes at room temperature (to remove cytoplasmic RNA). Slices were then stained with 1 μg/ml of propidium iodide (Molecular Probes) in PBS for 30 minutes. Lens membrane architecture was visualized using a polyclonal antibody to aquaporin 0 (AQP0, Chemicon International) as described previously (Shiels et al., 2001).

Western blot analysis

GFP-expressing lenses were microdissected into three regions, using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (MSFLIII, Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA). The peripheral sample contained newly differentiated cells that expressed GFP in a variegated pattern. The innermost sample comprised core fiber cells with uniform fluorescence. A third, cortical, sample contained cells from the transitional region between the peripheral and core samples. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were probed sequentially with a polyclonal antibody to GFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and an horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. Antibody binding was visualized by chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Femto substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Membranes were subsequently stripped and reprobed with a monoclonal antibody against succinate dehydrogenase (anti-SDH(Fp), Molecular Probes).

Results

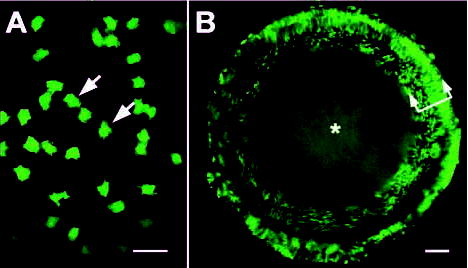

Transgenic TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mice were crossed with wild-type animals to generate mice that were hemizygous for the GFP transgene. Under blue light examination, bright GFP fluorescence was readily detected in regions of exposed skin and the eyes of hemizygous animals. Within the eye, GFP was expressed in the cornea, retina and lens. Lenses from hemizygous animals were indistinguishable in size and shape from wild-type lenses, and cataracts were not observed, suggesting that transgene expression did not significantly disturb the cellular or molecular organization of the lens. On closer observation by confocal microscopy, it was evident that not all lens cells expressed GFP. The heterogeneous expression of GFP resulted in a mosaic fluorescence pattern in the lens epithelium (Fig. 1A). The proportion of epithelial cells expressing GFP varied from 20% to 50%. During lens growth, the fiber cells, which make up the bulk of the tissue, are derived directly from cells at the margin of the lens epithelium. Unsurprisingly, therefore, newly formed fibers (i.e. those nearest the surface of the tissue) also exhibited GFP mosaicism, with approximately the same ratio of expressing to nonexpressing cells as observed in the lens epithelium (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the mosaicism that characterized the superficial layers, the lens core region was weakly but uniformly fluorescent.

Fig. 1.

Variegated expression of a GFP transgene in the lens of hemizygous TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mice. (A) En face confocal view of the lens epithelium. Individual GFP-expressing cells are evident (arrows). Nonexpressing cells occupy the spaces between the fluorescent cells. The proportion of GFP-expressing epithelial cells varied from 20–50%. (B) Confocal image of a living, intact, P1 lens imaged in the equatorial plane. Note the variegated GFP expression pattern in the outer cortex (arrows) and the reduced, but uniform, fluorescence in the lens core (*). Bars, A, 25 μm; B, 100 μm.

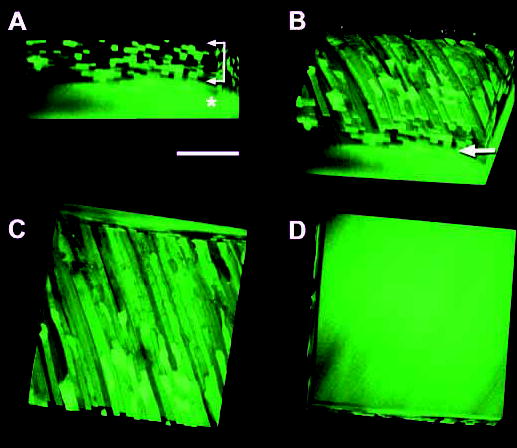

We examined in detail the border between the variegated fluorescence of the surface layers and the uniform fluorescence of the lens core. Using confocal microscopy and high N.A. water immersion objective lenses, we optically sectioned through this region in intact living lenses and reconstructed the cellular architecture in three dimensions. Four projections of a volume rendered image are shown in Fig. 2. Individual GFP-expressing fiber cells were homogeneously fluorescent along their lengths. Near the surface of the lens, fluorescent cells were interspersed with nonfluorescent cells, resulting in a checkerboard appearance when viewed end on (Fig. 2A). At depths of approximately 100 μm and greater, individual GFP-expressing and nonexpressing cells were no longer discernible and all cells were incorporated into a core region of uniform fluorescence (Fig. 2A–D).

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of GFP cellular fluorescence in the outer cortex of a one-month-old TgN(GFPU)5Nagy hemizygous mouse lens. (A) Viewed end on, the variegated expression of GFP in superficial fiber cells results in a checkerboard fluorescence pattern (arrows) due to the interposition of nonexpressing cells between GFP-expressing cells. In the deeper cell layers the fluorescence is uniform (*). (B) By rotating the volume, the elongated morphology of the fiber cells becomes evident. Note the sharp transition (arrow) between the discrete labeling pattern of individual fibers in the superficial tissue and the homogeneous fluorescence of cells in the deep cortex. (C) GFP-expressing cells are uniformly fluorescent along their lengths, although regions of the fibers that contact the surface of the reconstructed volume appear somewhat brighter. (D) Viewed from beneath; the cytoplasmic fluorescence in the fibers is uninterrupted. At this depth (approximately 125 μm), all fibers contain GFP. Bar, 100 μm

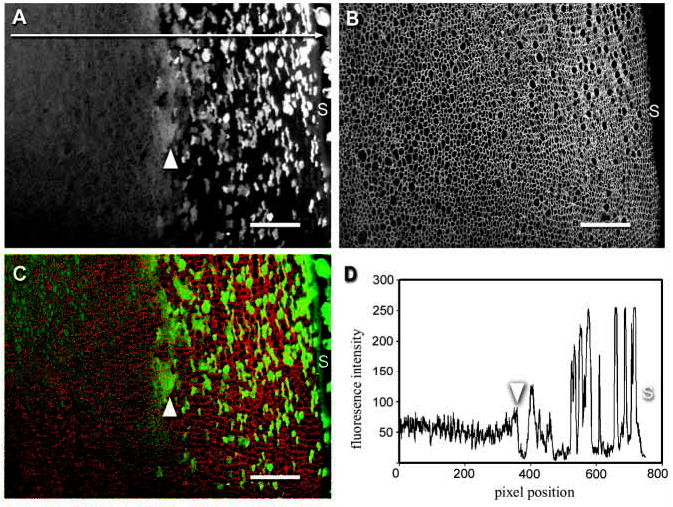

The diffuse fluorescence observed in the deeper cell layers (Fig. 2) suggested that GFP was present in all the cells of the lens core. However, the lens is an optically active tissue and it was conceivable that the uniform fluorescence observed in the lens core was an optical artifact arising from reduced image resolution in the deeper cell layers. To address this issue, lenses were fixed and mechanically sectioned in the equatorial plane. Lens slices were incubated with an antibody against AQP0, an abundant integral protein of the fiber cell membrane. The distributions of GFP and AQP0 were covisualized in the lens cortex (Fig. 3). The distribution of GFP in lens slices (Fig. 3A) was consistent with the 3D reconstructions obtained from living intact lenses (Fig. 2). This suggests that the transition from the peripheral variegated fluorescence pattern to the uniform fluorescence of the core reflected real differences in the distribution of GFP. Pixel intensity measurements on either side of the transition region indicated that the average fluorescence in the peripheral cell layer was close to that of the core region (Fig. 3D). This is consistent with the notion that the transition region (indicated by an arrowhead in Fig. 3A) marks the point at which GFP is redistributed into cells that did not originally express it.

Fig. 3.

Covisualization of GFP fluorescence and AQP0 immunofluorescence in a fixed, equatorial lens slice from a P7 TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mouse. (A) GFP expression in fiber cells in the outer cortex. Near the lens surface (S), GFP-expressing fiber cells are interspersed with nonexpressing cells. Approximately 150 μm below the surface there is a transition (arrowhead) to a diffuse pattern of fluorescence in which all cells are weakly fluorescent. (B) Immunofluorescence detection of AQP0, an intrinsic lens membrane protein, highlights the membrane organization in this region of the lens. In equatorial sections lens fiber cells are seen in cross section. (C) Merged image of endogenous GFP fluorescence (green) and AQP0 immunofluorescence (red). Note that the transition (arrowhead) from the mosaic GFP fluorescence pattern that characterizes the superficial cells to the diffuse distribution in the inner cells is not associated with a marked change in the cross-sectional profiles of the fibers. (D) Pixel intensity histogram of GFP fluorescence collected along the line indicated in A. The average fluorescence intensity does not differ markedly in cells located either side of the transition region (arrowhead). In this example, at pixel positions >385, the average fluorescence intensity was 70.9±71.0 At pixel positions <385, the average intensity was 52.5±14.9. Bars in A, B, C, 50 μm.

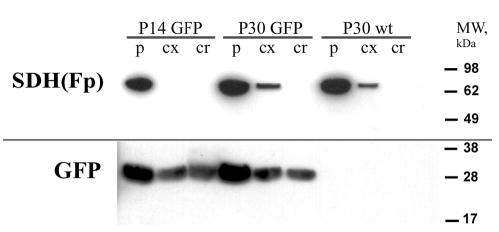

Because the lens cortex is known to be a region of active proteolysis, we examined whether the abrupt change in distribution of GFP observed in the transition region(arrowhead Fig. 3A) was associated with proteolysis of the GFP molecule. Samples were microdissected from the peripheral region (p), the lens cortex (cx) and the core (cr) and separated by SDS-PAGE. A polyclonal GFP antibody was used to examine the distribution of GFP in these regions (Fig. 4). To verify the accuracy of the dissections, blots were probed subsequently with an antibody against succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein, a mitochondrial marker. Mitochondria are abundant in the peripheral lens fibers but absent from the core of the lens (Bassnett and Beebe, 1992). Lenses from 2-week-old or 1-month-old TgN(GFPU)5Nagy and wild-type mice were examined. At both ages, the GFP antibody recognized a single band at 27 kDA, the size of the intact GFP molecule (Prasher et al., 1992). Full-sized GFP was present throughout the lens, including the oldest cells in the lens – those of the lens core. The band was absent from age-matched wild-type control lens samples. No evidence of proteolytic breakdown products of GFP was observed in any of the samples. As expected, succinic dehyrogenase was abundant in the mitochondria-rich peripheral tissue, less abundant in the cortex and completely absent from the organelle-free lens core. These data indicated that the redistribution of GFP in the lens cortex was not due to proteolysis of GFP.

Fig. 4.

GFP proteolysis does not occur during fiber cell differentiation. Lenses from P14 or P30 TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mice or wild-type controls were separated into three regions. The peripheral sample (p) contained the region of variegated GFP expression. The core sample (cr) was from the center of the lens and contained cells of uniform fluorescence. A cortex sample (cx) was obtained from a region intermediate between the peripheral and core samples. Blotted samples were probed with antibodies against the mitochondrial marker SDH(Fp) or GFP (see text for details). SDH(Fp) was abundant in the peripheral samples from transgenic or wild-type lenses, reduced in the cortex and absent from the core. The GFP antibody identified a single band of the expected size (27 kDa) in samples from the TgN(GFPU)5Nagy lenses. This band was absent from the wild-type controls. Full-sized GFP was present in samples from each region of the transgenic lenses, including the oldest cells in the lens, those of the core. No evidence of proteolytic breakdown products was observed. The results are representative of three experiments.

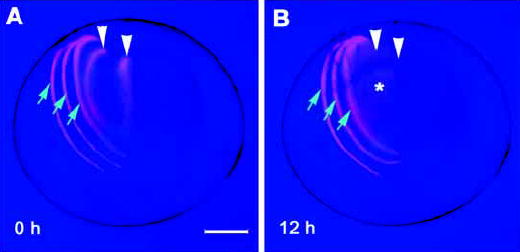

There are two plausible explanations for the abrupt transformation from the variegated fluorescence of the superficial layers to the uniform fluorescence of the lens core. First, it is possible that those fiber cells that did not express GFP in the superficial layers began to express GFP when buried to a depth of >100 μm. Alternatively, in this region, a pathway that permitted the intercellular exchange of GFP may have been established between expressing and nonexpressing cells. To differentiate between these hypotheses, we probed cell-cell communication on either side of the transitional zone using a dye-injection technique. The fluorescent marker, TMRD (10 kDa), was injected iontophoretically into fiber cells at different depths in the wild-type lens (Fig. 5A). The TMRD molecule is too large to pass through gap junctions. The diffusion of TMRD was followed by time-lapse microscopy over a 12 hour incubation period. In the ~10 minute period required to complete the injections and photograph the lens, TMRD had already begun to diffuse from injected core fiber cells (Fig. 5A). After 12 hours, the sites of the original core injections were no longer discernible. Instead, a diffuse cloud of TMRD fluorescence, encompassing many fiber cells, filled much of the lens core. By contrast, TMRD injected into peripheral fiber cells was well retained, even after the 12 hour incubation period (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Intercellular diffusion of macromolecules is observed between fibers located deep within the lens but not between superficial cells. (A) Injections of 10 kDa TMRD (red) were made into individual fiber cells situated at different depths below the surface of a living P2 lens. The 0 hour time point is a nominal value. It took approximately 10 minutes to complete the injections and photograph the lens. During the interim TMRD had already begun to diffuse from injected cells in the lens core (arrowheads). (B) TMRD injected into surface cells (blue arrows) was well retained, even 12 hours after the injection. By contrast, TRMD was not retained by injected cells in the center of the lens (arrowheads) and, after 12 hours, formed a diffuse cloud of fluorescence in the lens core (*). The results are representative of 12 experiments. Bar, 250 μm.

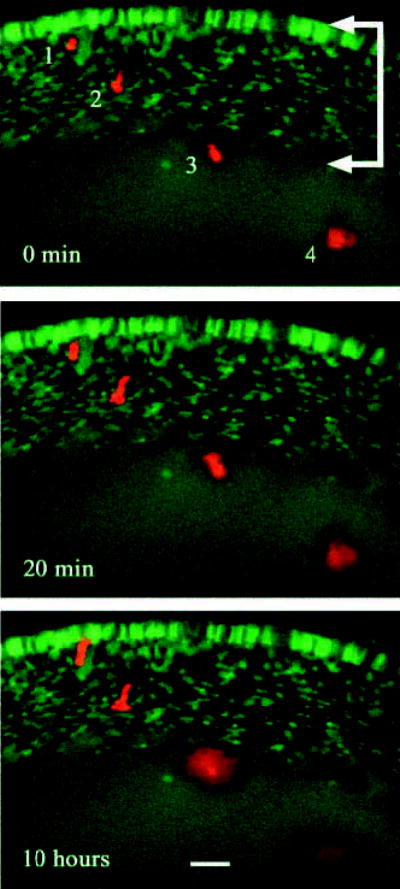

To more directly correlate the dye-coupling results with the GFP labeling pattern, we microinjected TMRD into GFP mosaic lenses (Fig. 6). Four or five intracellular injections were made into progressively deeper cell layers, whereas the transitional zone was imaged simultaneously by confocal microscopy. The diffusion of injected TMRD was visualized in time-lapse by confocal microscopy. When injections were made within the mosaic zone at the lens periphery, injected cells retained the dye. By contrast, injections beneath the variegated layer into the uniformly fluorescent region resulted in extensive diffusion of the injected dye into the cytoplasm of neighboring cells. These results supported the hypothesis that the transitional zone marked the appearance of a cell-cell communication pathway that was permeable to macromolecules. Presumably, therefore, in GFP mosaic animals, the transformation from the checkerboard fluorescence pattern at the periphery to the uniform fluorescence pattern in the core was the result of redistribution of GFP from expressing cells into nonexpressing cells. If this is the case, then the border of the uniformly fluorescent core of the lens marked the boundary of a syncytial region within which large molecules were free to diffuse.

Fig. 6.

Intercellular diffusion of 10 kDa TMRD occurs only in the uniformly labeled core region of TgN(GFPU)5Nagy hemizygous mouse lenses. Four fiber cells located at various depths below the surface of a P2 transgenic lens were injected with TMRD (red). Intrinsic GFP fluorescence (green) and TMRD fluorescence were covisualized during a 10 hour period in organ culture. Cell #1 and cell #2 were located in the variegated layer (arrows) at the lens surface. In these cells, TMRD fluorescence was retained over the course of the experiment. Cell #3 and cell #4 were located deeper below the lens surface. Cell #3 lay just within the region of uniform GFP fluorescence and cell #4 was located approximately 80 μm within the uniform region. Over the 10 hour culture period, TRMD fluorescence was not retained by cell #3 or cell #4. At the end of the experiment, TMRD fluorescence was visible as a diffuse cloud that had spread well beyond the boundaries of the injected cells. Bar, 25 μm.

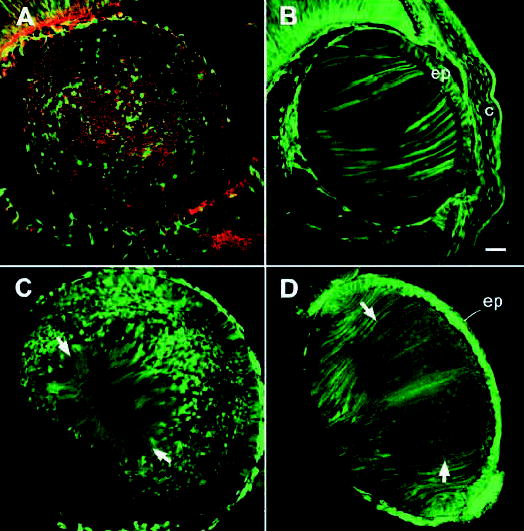

At E14, the majority of the fiber cell mass consists of primary fibers that span the full axial width of the lens from the anterior epithelium to the posterior capsule. Sutures are not present at this age. Confocal microscopy of the E14 lens revealed that individual scattered fiber cells expressed GFP. In equatorial views (Fig. 7A), the variegated expression of GFP resulted in fluorescence mosaicism due to the juxtaposition of expressing and nonexpressing cells. In midsagittal views, the fiber cells had a striped appearance (Fig. 7B). However, as development progressed, a uniform labeling pattern replaced the discrete labeling of individual fiber cells in the core region of the lens. This phenomenon was observed occasionally in E15 lenses but consistently by E16 (Fig. 7C, D). Interestingly, the transformation in the labeling pattern occurred in cells that had recently detached from the lens capsule.

Fig. 7.

Establishment of the macromolecular permeable pathway in the core of the lens during embryonic development. (A) At E14, GFP is expressed in a mosaic pattern. In equatorial sections, discretely labeled individual fiber cells are evident, scattered throughout the lens. This section was colabeled with fluorescent phalloidin (red) to visualize the organization of non-GFP-expressing cells (red). (B) In midsagittal sections, the fiber mass has a striped appearance, due to the juxtaposition of GFP-expressing and nonexpressing cells. (C) By E16, the fluorescence labeling pattern had transformed, such that the central fiber cells (situated between the arrows) are now uniformly labeled. (D) The uniformly fluorescent core region is also evident in mid-sagittal sections. Note that the region of uniform fluorescence contains fiber cells (arrows) that have recently detached from the posterior capsule. c, cornea; ep, lens epithelium. Bar, 50 μm.

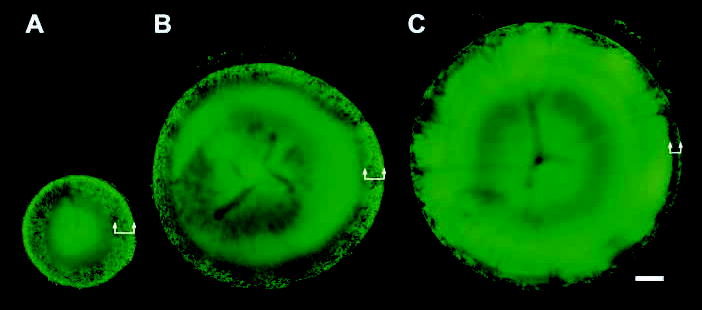

Once established in the lens core during embryonic development, the syncytial region expanded, encompassing additional fiber cells during postnatal lens growth (Fig. 8). At all ages examined, a region of variegated fluorescence was maintained in a thin layer near the surface of the tissue.

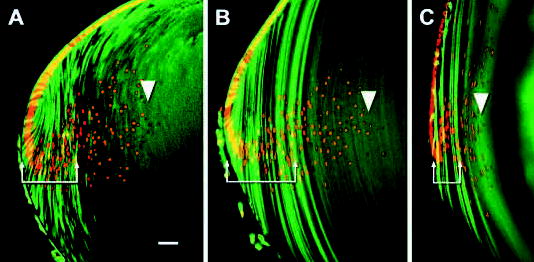

Fig. 8.

The syncytial region expands during postnatal development. Fluorescence within living lenses from one-day-old (A), one-month-old (B) and six-month-old (C) hemizygous TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mice was imaged in the equatorial plane by confocal microscopy. Although the uniformly labeled lens core expands with age, the thickness of the variegated layer at the periphery (arrows) thins slightly over this period. The fluorescence in the center of the oldest lenses appears to be diminished with respect to the cortical cells. Bar, 250 μm.

Because nuclei and other organelles are degraded during terminal differentiation (Kuwabara and Imaizumi, 1974; Vrensen et al., 1991), nucleated cells are only found near the surface of the tissue. We sought to determine whether a complement of such cells was incorporated into the syncytial region in the lens core. By incubating midsagittal slices of the GFP mosaic lenses with propidium iodide, we visualized the distribution of nuclei in relation to the diffusely fluorescent core region (Fig. 9). At all ages examined, a significant proportion of the nucleated fiber cells of the lens were located within this region. The overall dimensions of the diffusely labeled core, the thickness of the variegated surface layer and the thickness of the nucleated region of the core are shown in Fig. 10. In adult mice, the distance from the surface of the lens to the border of the diffusely labeled core was approximately90 μm at the equator and the layer of nucleated cells within the core was approximately 100 μm thick.

Fig. 9.

A significant proportion of nucleated fiber cells are contained within the syncytial core of the lens. Vibratome slices of fixed hemizygous TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mouse lenses were incubated with propidium iodide to allow the distribution of fiber cell nuclei (red) and intrinsic GFP fluorescence (green) to be covisualized. At all ages examined, the cytoplasmic fluorescence in the outer cell layers had a striped appearance (arrows) due to the variegated expression of the GFP transgene. The nuclear bow region was clearly visible and propidium-stained nuclei extended well into the region of uniform GFP fluorescence. The position of the last nucleated fiber cell is indicated (arrowhead). A, P1 lens; B, P7 lens; C, adult lens. Bar, 50 μm.

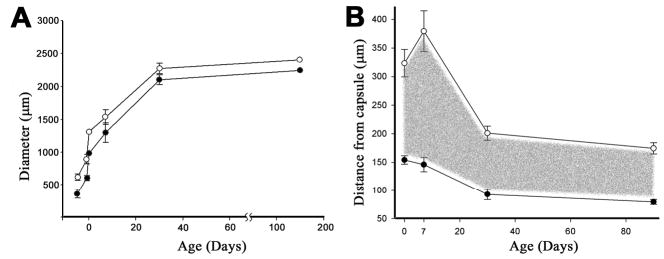

Fig. 10.

Developmental dynamics of the syncytial region in the mouse lens. (A) The equatorial diameter of the lens (open symbols) and the uniformly labeled syncytial region (closed symbols) were measured in embryonic and adult lenses. The region expanded during development, closely matching the overall growth rate of the lens. (B) The thickness of the variegated region (filled symbols) decreased during early postnatal development before stabilizing at approximately 90 μm in adult lenses. The thickness of the nucleated cell layer (open symbols) also stabilized in older animals at approximately 180 μm. The layer of nucleated cells within the syncytial region (indicated by the shaded area) was approximately 90 μm thick. Data points represent the mean±s.d. (n>8 lenses for each time point).

Discussion

In this study we observed that in the lenses of hemizygous TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mice, the expression of the GFP transgene was intrinsically mosaic, resulting in the random labeling of scattered epithelial and fiber cells. A similar phenotype was recently reported in the cornea of TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mice (Nagasaki and Zhao, 2003). The mosaic expression pattern allowed us to visualize the formation of an intercellular pathway in the lens that was permeable to macromolecules. We hypothesize that, owing to the presence of such a pathway, the core region of the lens may function as a syncytium with respect to the diffusion of macromolecules.

The molecular mechanism responsible for mosaicism in the TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mouse is not known, neither is the site of insertion nor copy number of the transgene. However, random shutoff of transgene expression has been noted frequently in genetically modified eukaryotes (Milot et al., 1996; Pravtcheva et al., 1994). Random transgene silencing by heterochromatin has been attributed to a phenomenon called position effect variegation (Allshire et al., 1994; Festenstein et al., 1996; Robertson et al., 1995). We are not aware of any reports that describe the reactivation of previously silenced transgenes during development. On the contrary, the proportion of transgene-expressing cells typically decreases with age (Robertson et al., 1996). It seems unlikely, therefore, that the transgene silencing mechanism is inactivated during fiber cell differentiation. Consequently, we believe that the sudden appearance of GFP in the cytoplasm of previously nonexpressing cortical fiber cells is due to the redistribution of protein from neighboring expressing cells.

Lens fiber cells are coupled by gap junctions. Although gap junctions do not allow the passage of macromolecules, they might conceivably allow intercellular diffusion of small proteolytic fragments of the GFP parent molecule. The lens cortex is a region of intracellular proteolysis, and indirect evidence for the activation of caspase and calpain proteases has been reported (Lin et al., 1997; Yin et al., 2001). However, in the present study, western blot analysis of GFP extracted from fiber cells at various stages of differentiation showed no evidence of GFP proteolysis. This may be due to the β-barrel tertiary structure of the GFP molecule, which renders it extremely resistant to proteolysis (Bokman and Ward, 1981; Chalfie et al., 1994; Chiang et al., 2001). Disturbance of the tertiary structure results in complete loss of GFP fluorescence (Cubitt et al., 1995; Tsien, 1998). Thus, even if proteolytic fragments of GFP were to be produced in the lens, the fragments would be unlikely to fluoresce and would not, therefore, be detected microscopically. Together, these observations suggest that the redistribution of cellular fluorescence observed in the current study reflects the movement of intact GFP molecules. It follows that this could not be due to gap junction-mediated communication. This notion was further supported by the results of microinjection experiments in which a 10 kDa dextran was only observed to diffuse between fibers located at depths of >100 μm from the lens surface. It was in this location that the intercellular redistribution of GFP was first observed.

The macromolecule-permeable pathway first became patent during embryonic development and, from E15 onwards, the core of the lens functioned as a syncytium with respect to the diffusion of TMRD and GFP. By adulthood, the syncytial region had expanded to encompass the majority of the tissue volume including, significantly, the most deeply situated nucleated fiber cells. In the chicken embryo lens, fiber cells are able to express exogenous genes until immediately before they lose their organelles (Shestopalov and Bassnett, 2000). If mouse lens fiber cells are also transcriptionally and translationally competent until the point of denucleation, it implies that a contingent of cells within the syncytial region is synthetically active. In principle, newly synthesized proteins produced by this layer of active cells could refresh the pool of cytoplasmic protein in the anucleated central cells. In this regard, it is noteworthy that several metabolic labeling studies have detected newly synthesized proteins in samples extracted from the lens core (Laurent et al., 1987; Lieska et al., 1992; Ozaki et al., 1985; Shinohara et al., 1982). Cells in the center of the lens contain neither nuclei nor any other cytoplasmic organelles. It is possible, therefore, that the presence of newly synthesized proteins in this region could be due to diffusion from the synthetically active surface layers. If this is correct, the term metabolic cooperation, originally coined to describe the exchange of ions and small molecules between the metabolically active surface cells of the lens and the quiescent inner fibers (Goodenough et al., 1980), may have to be expanded to include the exchange of macromolecules. However, there is currently no direct experimental evidence that exchange of proteins occurs in vivo. Long-term metabolic labeling experiments will be required to assess the potential physiological importance of this phenomenon.

The physical nature of the macromolecule-permeable pathway is not known. In other vertebrate systems, syncytia result from incomplete separation of dividing cells or the fusion of plasma membranes. Because fiber cells are postmitotic when they are amalgamated into the lens syncytium, the latter possibility seems more likely. Previous morphological studies revealed the presence of fusions between neighboring fiber cells (Kuszak et al., 1985). Regions of cytoplasmic continuity would facilitate the exchange of macromolecules and, therefore, represent a plausible explanation for the data presented here. Cellular fusions underlie the development of many syncytia, including skeletal muscle (Fischer-Lougheed et al., 2001; Kalderon and Gilula, 1979), placental syncytiotrophoblasts (Knerr et al., 2002), alveolar macrophages and bone osteoblasts (Vignery, 2000). In the lens, fusions are more commonly observed in centrally located cells than in peripheral cells (Shestopalov and Bassnett, 2000). This observation also correlates well with the results of the present GFP labeling and dye injection experiments. However, due to the length of the fiber cells, it has proved difficult to quantify the number and distribution of fusions, and in no case has it been shown that all fiber cells are fused. By contrast, all fiber cells are incorporated into the syncytial region, as judged by the uniform labeling of the lens core. Notwithstanding this discrepancy, membrane fusions between core fiber cells represent the most parsimonious explanation for the results reported here.

Despite significant differences in lens morphology between species, the syncytial organization of the mouse lens core appears to resemble that described recently in the embryonic chicken lens (Shestopalov and Bassnett, 2000). In both cases, intercellular diffusion of macromolecules is first observed in the primary fiber cells during embryonic development, shortly after the cells detach from the lens capsule. In secondary fiber cells, the macromolecule-permeable pathway is established relatively late in the cell differentiation process, but before fiber cells degrade their organelles. The current study also showed that the syncytial organization persists in the adult lens. Taken together, the two studies suggest that syncytial organization in the lens core may be a universal feature of the vertebrate lens.

The physiological role of the macromolecule permeable pathway is not known. In addition to the potential role in the delivery of newly synthesized proteins alluded to above, it has been speculated that the exchange of proteins may serve to equalize small differences in refractive index between neighboring cells and thereby enhance the transparency of the lens (Shestopalov and Bassnett, 2000).

Several electrical impedance studies have mapped cell-cell resistance within the lens tissue as a function of depth (Baldo and Mathias, 1992; Duncan et al., 1981). Such studies have failed to provide evidence for the appearance of a novel conductive pathway between cells in the lens core. Indeed, in the mouse lens, the coupling conductance of the outer fiber cells is significantly higher than that of the core fibers (Baldo et al., 2001). Without knowing the physical nature of the macromolecule permeable pathway it is difficult to judge whether impedance experiments such as these are compatible with the syncytial organization proposed here. Even if the exchange of macromolecules within the lens core occurs via electrically conductive cytoplasmic bridges, the contribution of such structures to the overall impedance characteristics of the lens is difficult to assess. The contribution would depend on the abundance and distribution of the putative cytoplasmic bridges relative to the gap junction mediated pathway.

Lens gap junctional coupling is sensitive to pH (Baldo and Mathias, 1992; Bassnett and Duncan, 1988) but this sensitivity is lost in the lens core (Baldo et al., 2001; Baldo and Mathias, 1992). These data could provide support for a model of the lens in which cell communication in the peripheral layers is dependent on gap junctions but supplemented, in the core, by a pH-insensitive pathway. Cytoplasmic bridges would constitute such a pathway. However, it has also been suggested that the cleavage of connexin proteins in the cortical fibers yields gap junctions with reduced pH sensitivity (Lin et al., 1998). Thus, the pH insensitivity of intercellular communication in the core cannot be used to differentiate between gap junction-mediated and gap- junction-independent mechanisms in this region.

In the center of the lens, the macromolecule permeable pathway probably operates in parallel with gap-junction-mediated communication. However, the two pathways of intercellular communication may not be completely independent. Impedance studies on lenses from α3 knockout mice showed that the coupling conductance in the mature fibers is close to zero. Furthermore, this fiber cell population was depolarized with respect to the overlying cells and ultimately opacified (Baldo et al., 2001; Gong et al., 1998). These electrophysiological data show that α3 connexin is absolutely required for intercellular communication in the lens core. It is not known whether intercellular diffusion of macromolecules occurs in the core of lenses from the α3 connexin knockout mice. If it does, it would suggest that intercellular macromolecular diffusion is mediated by an electrically silent mechanism. Alternatively, if diffusion of macromolecules is blocked in the α3 connexin knockout animals, it may suggest that connexin expression is required for the formation of the macromolecule permeable pathway. In this regard, it is interesting to note that gap junction mediated communication is a necessary prerequisite for successful myoblast fusion in the development of syncytial muscle cells (Mege et al., 1994)

Interestingly, previous electron microscopic studies in lens fiber cells have suggested that gap-junction plaques may be the initiation site for lens membrane fusion (Kuszak et al., 1985). Future experiments in which α3 connexin (–/–) animals are crossed with TgN(GFPU)5Nagy mice should allow some of these questions to be resolved directly.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peggy Winzenburger for her expert technical assistance. This study was supported by NIH grants EY12260 (S.B.), EY 14232 (V.S.), EY02687 (Core Grant for Vision Research) and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness. S.B. is a RPB William and Mary Greve Scholar.

References

- Allshire RC, Javerzat JP, Redhead NJ, Cranston G. Position effect variegation at fission yeast centromeres. Cell. 1994;76:157–169. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo GJ, Mathias RT. Spatial variations in membrane properties in the intact rat lens. Biophys J. 1992;63:518–529. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81624-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo GJ, Gong X, Martinez-Wittinghan FJ, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Mathias RT. Gap junctional coupling in lenses from alpha(8) connexin knockout mice. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:447–456. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.5.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassnett S. Lens organelle degradation. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:1–6. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassnett S, Duncan G. The influence of pH on membrane conductance and intercellular resistance in the rat lens. J Physiol. 1988;398:507–521. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassnett S, Beebe DC. Coincident loss of mitochondria and nuclei during lens fiber cell differentiation. Dev Dyn. 1992;194:85–93. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001940202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassnett S, Missey H, Vucemilo I. Molecular architecture of the lens fiber cell basal membrane complex. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2155–2165. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.13.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti EL, Dunia I, Bloemendal H. Development of junctions during differentiation of lens fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:5073–5077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.12.5073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti EL, Dunia I, Bentzel CJ, Vermorken AJ, Kibbelaar M, Bloemendal H. A portrait of plasma membrane specializations in eye lens epithelium and fibers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;457:353–384. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(76)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry V, Mackay D, Khaliq S, Francis PJ, Hameed A, Anwar K, Mehdi SQ, Newbold RJ, Ionides A, Shiels A, et al. Connexin 50 mutation in a family with congenital “zonular nuclear” pulverulent cataract of Pakistani origin. Hum Genet. 1999;105:168–170. doi: 10.1007/s004399900094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokman SH, Ward WW. Renaturation of Aequorea gree-fluorescent protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;101:1372–1380. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Wang X, Hawes NL, Ojakian R, Davisson MT, Lo WK, Gong X. A Gja8 (Cx50) point mutation causes an alteration of alpha 3 connexin (Cx46) in semi-dominant cataracts of Lop10 mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:507–513. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CF, Okou DT, Griffin TB, Verret CR, Williams MN. Green fluorescent protein rendered susceptible to proteolysis: positions for protease-sensitive insertions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;394:229–235. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubitt AB, Heim R, Adams SR, Boyd AE, Gross LA, Tsien RY. Understanding, improving and using green fluorescent proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:448–455. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahm R, van Marle J, Prescott AR, Quinlan RA. Gap junctions containing alpha8-connexin (MP70) in the adult mammalian lens epithelium suggests a re-evaluation of its role in the lens. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:45–56. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G. The site of the ion restricting membranes in the toad lens. Exp Eye Res. 1969;8:406–412. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(69)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Patmore L, Pynsent PB. Impedance of the amphibian lens. J Physiol. 1981;312:17–27. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festenstein R, Tolaini M, Corbella P, Mamalaki C, Parrington J, Fox M, Miliou A, Jones M, Kioussis D. Locus control region function and heterochromatin-induced position effect variegation. Science. 1996;271:1123–1125. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Lougheed J, Liu JH, Espinos E, Mordasini D, Bader CR, Belin D, Bernheim L. Human myoblast fusion requires expression of functional inward rectifier Kir2.1 channels. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:677–686. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Li E, Klier G, Huang Q, Wu Y, Lei H, Kumar NM, Horwitz J, Gilula NB. Disruption of alpha3 connexin gene leads to proteolysis and cataractogenesis in mice. Cell. 1997;91:833–843. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Baldo GJ, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Mathias RT. Gap junctional coupling in lenses lacking alpha3 connexin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15303–15308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough DA. The crystalline lens. A system networked by gap junctional intercellular communication. Semin Cell Biol. 1992;3:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4682(10)80007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough DA, Dick JS, II, Lyons JE. Lens metabolic cooperation: a study of mouse lens transport and permeability visualized with freeze-substitution autoradiography and electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:576–589. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.2.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graw J, Loster J, Soewarto D, Fuchs H, Meyer B, Reis A, Wolf E, Balling R, Hrabe de Angelis M. Characterization of a mutation in the lens-specific MP70 encoding gene of the mouse leading to a dominant cataract. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:867–876. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruijters WT, Kistler J, Bullivant S. Formation, distribution and dissociation of intercellular junctions in the lens. J Cell Sci. 1987;88:351–359. doi: 10.1242/jcs.88.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjantonakis AK, Gertsenstein M, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Nagy A. Generating green fluorescent mice by germline transmission of green fluorescent ES cells. Mech Dev. 1998;76:79–90. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser RJ, Maurice DM. The diffusion of fluorescein in the lens. Exp Eye Res. 1964;3:156–165. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(64)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalderon N, Gilula NB. Membrane events involved in myoblast fusion. J Cell Biol. 1979;81:411–425. doi: 10.1083/jcb.81.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knerr I, Beinder E, Rascher W. Syncytin, a novel human endogenous retroviral gene in human placenta: evidence for its dysregulation in preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:210–213. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.119636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuszak J, Maisel H, Harding CV. Gap junctions of chick lens fiber cells. Exp Eye Res. 1978;27:495–498. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(78)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuszak JR, Macsai MS, Bloom KJ, Rae JL, Weinstein RS. Cell-to-cell fusion of lens fiber cells in situ: correlative light, scanning electron microscopic, and freeze-fracture studies. J Ultrastruct Res. 1985;93:144–160. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(85)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara T, Imaizumi M. Denucleation process of the lens. Invest Ophthalmol. 1974;13:973–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent M, Romquin N, Counis MF, Muel AS, Courtois Y. Collagen synthesis by long-lived mRNA in embryonic chicken lens. Dev Biol. 1987;121:166–173. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieska N, Krotzer K, Yang HY. A reassessment of protein synthesis by lens nuclear fiber cells [letter] Exp Eye Res. 1992;54:807–811. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90037-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JS, Fitzgerald S, Dong Y, Knight C, Donaldson P, Kistler J. Processing of the gap junction protein connexin50 in the ocular lens is accomplished by calpain. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73:141–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JS, Eckert R, Kistler J, Donaldson P. Spatial differences in gap junction gating in the lens are a consequence of connexin cleavage. Eur J Cell Biol. 1998;76:246–250. doi: 10.1016/s0171-9335(98)80002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay D, Ionides A, Kibar Z, Rouleau G, Berry V, Moore A, Shiels A, Bhattacharya S. Connexin46 mutations in autosomal dominant congenital cataract. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1357–1364. doi: 10.1086/302383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mege RM, Goudou D, Giaume C, Nicolet M, Rieger F. Is intercellular communication via gap junctions required for myoblast fusion? Cell Adhes Commun. 1994;2:329–343. doi: 10.3109/15419069409014208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milot E, Strouboulis J, Trimborn T, Wijgerde M, de Boer E, Langeveld A, Tan-Un K, Vergeer W, Yannoutsos N, Grosveld F, et al. Heterochromatin effects on the frequency and duration of LCR-mediated gene transcription. Cell. 1996;87:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki J, Takaki S, Araki K, Tashiro F, Tominaga A, Takatsu K, Yamamura K. Expression vector system based on the chicken beta-actin promoter directs efficient production of interleukin-5. Gene. 1989;79:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki T, Zhao J. Centripetal movement of corneal epithelial cells in the normal adult mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:558–566. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka T, Nishiura M, Ohkuma M. Gap junctions of lens fiber cells in freeze-fracture replicas. J Electron Microsc. 1976;25:35–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki L, Jap P, Bloemendal H. Protein synthesis in bovine and human nuclear fiber cells. Exp Eye Res. 1985;41:569–575. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(85)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal JD, Liu X, Mackay D, Shiels A, Berthoud VM, Beyer EC, Ebihara L. Connexin46 mutations linked to congenital cataract show loss of gap junction channel function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C596–C602. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson CA. Extracellular space of the crystalline lens. Am J Physiol. 1970;218:797–802. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.3.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatigorsky J. Lens differentiation in vertebrates. A review of cellular and molecular features. Differentiation. 1981;19:134–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1981.tb01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasher DC, Eckenrode VK, Ward WW, Prendergast FG, Cormier MJ. Primary structure of the Aequorea victoria green-fluorescent protein. Gene. 1992;111:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90691-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravtcheva DD, Wise TL, Ensor NJ, Ruddle FH. Mosaic expression of an Hprt transgene integrated in a region of Y heterochromatin. J Exp Zool. 1994;268:452–468. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402680606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae JL. The electrophysiology of the crystalline lens. Curr Top Eye Res. 1979;1:37–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees MI, Watts P, Fenton I, Clarke A, Snell RG, Owen MJ, Gray J. Further evidence of autosomal dominant congenital zonular pulverulent cataracts linked to 13q11 (CZP3) and a novel mutation in connexin 46 (GJA3) Hum Genet. 2000;106:206–209. doi: 10.1007/s004390051029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G, Garrick D, Wu W, Kearns M, Martin D, Whitelaw E. Position-dependent variegation of globin transgene expression in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5371–5375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G, Garrick D, Wilson M, Martin DI, Whitelaw E. Age-dependent silencing of globin transgenes in the mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1465–1471. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.8.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shestopalov VI, Bassnett S. Expression of autofluorescent proteins reveals a novel protein permeable pathway between cells in the lens core. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1913–1921. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.11.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels A, Bassnett S, Varadaraj K, Mathias R, Al-Ghoul K, Kuszak J, Donoviel D, Lilleberg S, Friedrich G, Zambrowicz B. Optical dysfunction of the crystalline lens in aquaporin-0-deficient mice. Physiol Genomics. 2001;7:179–186. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00078.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara T, Piatigorsky J, Carper DA, Kinoshita JH. Crystallin synthesis and crystallin mRNAs in galactosemic rat lenses. Exp Eye Res. 1982;34:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(82)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson I, Rose B, Loewenstein WR. Size limit of molecules permeating the junctional membrane channels. Science. 1977;195:294–296. doi: 10.1126/science.831276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele EC, Jr, Lyon MF, Favor J, Guillot PV, Boyd Y, Church RL. A mutation in the connexin 50 (Cx50) gene is a candidate for the No2 mouse cataract. Curr Eye Res. 1998;17:883–889. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.17.9.883.5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignery A. Osteoclasts and giant cells: macrophage-macrophage fusion mechanism. Int J Exp Pathol. 2000;81:291–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2000.00164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrensen GF, Graw J, de Wolf A. Nuclear breakdown during terminal differentiation of primary lens fibres in mice: a transmission electron microscopic study. Exp Eye Res. 1991;52:647–659. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TW, Goodenough DA, Paul DL. Targeted ablation of connexin50 in mice results in microphthalmia and zonular pulverulent cataracts. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:815–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Gu S, Jiang JX. Regulation of lens connexin 45.6 by apoptotic protease, caspase-3. Cell Commun Adhes. 2001;8:373–376. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]