Abstract

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a disorder characterized by both acute generalized, widespread activation of coagulation, which results in thrombotic complications due to the intravascular formation of fibrin, and diffuse hemorrhages, due to the consumption of platelets and coagulation factors. Systemic activation of coagulation may occur in a variety of disorders, including sepsis, severe infections, malignancies, obstetric or vascular disorders, and severe toxic or immunological reactions.

In this review, we briefly report the present knowledge about the pathophysiology and diagnosis of DIC. Particular attention is also given to the current standard and experimental therapies of overt DIC.

Background

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a disorder characterized by massive systemic intravascular activation of coagulation, leading to widespread deposition of fibrin in the circulation which can compromise the blood supply to various organs, thus contributing to multiple organ failure. At the same time, the consumption of platelets and coagulation proteins resulting from the ongoing coagulation may induce severe bleeding[1-6]. However, DIC is not a disease itself but is always secondary to an underlying disorder [7,8]. In fact, a variety of clinical conditions may cause systemic activation of coagulation. Table 1 lists the diseases most frequently associated with DIC. Bacterial infections, in particular septicemia, are the most common clinical conditions associated with DIC. There is no difference in the incidence of DIC in patients with Gram-negative or Gram-positive sepsis. Systemic infections by other micro-organisms, such as viruses and parasites, may also lead to DIC. The generalized activation of coagulation occurring in these cases is mediated by cell membrane components of micro-organisms (lipopolysaccharide or endotoxin) or bacterial exotoxins, such as staphylococcal α hemolysin, which cause a generalized inflammatory response through the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines [9-13]. Severe trauma and burns are other conditions frequently associated with DIC [14,15]. Both solid and hematologic cancers may be associated with DIC, which can complicate up to 15 percent of cases of metastasized tumors or acute leukemia [16-18]. DIC is also a frequent complication (occurring in more than 50 percent of cases) of some obstetric conditions such as abruptio placentae and amniotic fluid embolism [19,20]. Finally, selected vascular disorders, such as giant hemangiomas and large aortic aneurysms, and severe toxic or immunological reactions (snake bites, drugs, hemolytic transfusion reactions and transplant rejection) can be associated with DIC [2,8].

Table 1.

Clinical conditions associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation.

| Condition | Causes |

| Sepsis/severe infections | Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, spirochetes, rickettsiae, protozoa, fungi, viruses |

| Trauma | Polytrauma, neurotrauma, fat embolism, burns |

| Malignancy | Solid tumors, myeloproliferative/lymphoproliferative malignancies |

| Obstetric complications | Amniotic fluid embolism, abruptio placentae, placenta previa, retained dead fetus syndrome |

| Vascular disorders | Large vascular aneurysms, Kasabach-Merritt syndrome |

| Organ destruction | Severe pancreatitis, severe hepatic failure |

| Toxic reactions | Snake bites, recreational drugs |

| Immunologic reactions | Hemolytic transfusion reaction, transplant rejection |

In the following sections we briefly discuss the current knowledge on the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of DIC.

Pathogenesis of DIC

Most of the recent advances in our understanding ofthe pathogenesis of DIC are derived from studies in animal models and humans with severe sepsis [6]. These studies have demonstrated that the systemic formation of fibrin observed in this setting is the result of the simultaneous coexistence of four different mechanisms: increased thrombin generation, a suppression of the physiologic anticoagulant pathways, impaired fibrinolysis and activation of the inflammatory pathway [1,8,21].

The systemic generation of thrombin has been shown to be mediated predominantlyby the extrinsic (factor VIIa) pathway. In fact, while the abrogation of the tissue factor/factor VIIa pathway resulted in complete inhibition of thrombin generation in experimental animal models of endotoxemia, the inhibition of the contact system did not prevent systemic activation of coagulation [22,23].

Impaired function of physiological anticoagulant pathways may amplify thrombin generation and contribute to fibrin formation [24]. Plasma levels of antithrombin are markedly reduced in septic patients as a result of a combination of increased consumption by the ongoing formation of thrombin, enzyme degradation by elastase released from activated neutrophils, impaired synthesis due to liver failure and vascular capillary leakage [6,7,25]. Likewise, there may be significant depression of the protein C system, caused by enhanced consumption, impaired liver synthesis, vascular leakage and a down-regulation of thrombomodulin expression on endothelial cells by pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin(IL)-1β [26-28]. Moreover, the evidence that administration of recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) results in complete inhibition of endotoxin-induced thrombin generation suggests that tissue factor is involved in the pathogenesis of DIC [29,30]. Although no acquired or deficiency or functional defect of TFPI has been identified in patients with DIC, there is evidence that the inhibitor does not regulate tissue factor activity sufficiently in such patients[30].

As regards impaired fibrinolysis, experimental models of bacteremia and endotoxemia are characterized by rapidly increasing fibrinolytic activity, most probably due to the release of plasminogen activators from endothelial cells. However, this initialhyperfibrinolytic response is followed by an equally rapid suppression of fibrinolytic activity, due to the increase in plasma levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) [31-33]. The importance of PAI-1 in the pathogenesis of DIC is further demonstrated by the fact that a functional mutation in the PAI-1 gene, the 4G/5G polymorphism, which causes increased plasma levels of PAI-1, was linked to a worse clinical outcome in patients with meningococcal septicemia [34].

Finally, another important mechanism in the pathogenesis of DIC is the parallel and concomitant activation of the inflammatory cascade mediated by activated coagulation proteins, which in turn can stimulate endothelial cells to synthesize pro-inflammatory cytokines. In fact, while cytokines and inflammatory mediators can induce coagulation, thrombin and other serine proteasesinteract with protease-activated receptors on cell surfaces to promote further activation and additional inflammation [35]. Furthermore, since activated protein C has an anti-inflammatory effect through its inhibition of endotoxin-induced production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 by cultured monocytes/macrophages, depression of the protein C system may result in a pro-inflammatory state [36].

Thus, inflammatory and coagulation pathways interact with each other in a vicious circle which amplifies the response further and leads to dysregulated activation of systemic coagulation [37]. Table 2 summarizes the most important mechanisms in the pathogenesis of DIC in sepsis.

Table 2.

Pathogenesis of disseminated intravascular coagulation in sepsis.

| Mechanism | Pathophysiology |

| 1) Increased thrombin generation | Mediated predominantlyby tissue factor/factor VIIa pathway |

| 2) Impaired function of physiological anticoagulant pathway | |

| a) Reduction of antithrombin levels | The result of a combination of increased consumption, enzyme degradation, impaired liver synthesis and vascular leakage |

| b) Depression of protein C system | The result of a combination of increased consumption, impaired liver synthesis, vascular leakage and down- regulation of thrombomodulin |

| c) Insufficienttissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) | |

| 3) Impaired fibrinolysis | Mediated by release of plasminogen activators from endothelial cells immediately followed by an increase in the plasma levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) |

| 4) Activation of inflammatory pathway | Mediated by activated coagulation proteins and by depression of the protein C system |

However, there is evidence that various events, including the release of tissue material (fat, phospholipids, cellular enzymes) into the circulation, hemolysis and endothelial damage may promote the systemic activation of coagulation in severe trauma and burns through a mechanism similar to that observed in septic patients (i.e., systemic activation of cytokines)[14,15]. Nevertheless, there may also be specific variations in the pathogenesis if DIC due to different underlying disorders. For example, in some patients with cancer the initiation of coagulation activation is not only due to tissue factor expression on the surface of the malignant cells but in this case also involves a specific cancer procoagulant, a cysteine protease with factor X activating properties[38]. Patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia have a peculiar form of DIC characterized by a severe hyperfibrinolytic state associated with systemic activation of coagulation[17].

Diagnosis of DIC

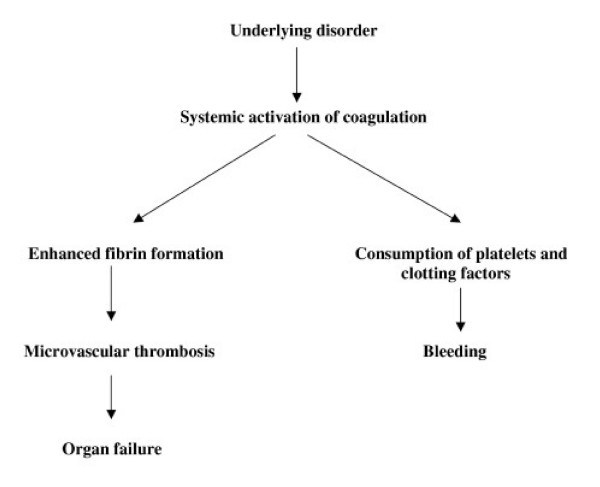

The most common clinical manifestations of DIC are bleeding, thrombosis or both, often resulting in dysfunction of one or more organs [39,40]. A schematic representation of the clinical manifestations of coagulation abnormalities in DIC is presented in Figure 1. Since no single laboratory test or set of tests is sensitive or specific enough to allow a definite diagnosis of DIC, in most cases the diagnosis is based on the combination of results of laboratory investigations in a patient with a clinical condition known to be associated with DIC [2,8]. The classical characteristic laboratory findings include prolonged clotting times (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time), increased levels of fibrin-related markers (fibrin degradation products [FDP], D-dimers), low platelet count and fibrinogen levels and low plasma levels of coagulation factors (such as factors V and VII) and coagulation inhibitors (such as antithrombin and protein C) [7,41]. However, the sensitivity of plasma fibrinogen levels for the diagnosis of DIC is low, since fibrinogen acts as an acute-phase reactant and its levels are often within the normal range for a long period of time. Thus, hypofibrinogenemia is frequently detected only in very severe cases of DIC [2,4]. On the other hand, FDP and D-dimer levels have a low specificity since many other conditions, such as trauma, recent surgery, inflammation or venous thromboembolism, are associated with elevated levels of these fibrin-related markers. Other, more specialized and useful tests, not available in all laboratories, include the measurement of soluble fibrin and assays of thrombin generation, such as those to detect prothrombin activation fragments F1+2 or thrombin-antithrombin complexes [42,43]. However, serial coagulation tests may bemore helpful than single laboratory results in establishing the diagnosis of DIC. A scoring system for the diagnosis of DIC, developed from a previously described set of diagnostic criteria [44], has been proposed by the Scientific Subcommittee on DIC of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) [45,46]. This system consists of a five-step diagnostic algorithm (see also Figure 2), in which a specific score, reflecting the severity of the abnormality found, is given to each of the following laboratory tests: platelet count (>100 × 109/L = 0; <100 × 109/L = 1, <50 × 109/L = 2), elevated fibrin-related markers (e.g. soluble fibrin monomers/fibrin degradation products) (no increase = 0; moderate increase = 2; strong increase = 3), prolonged prothrombin time (< 3 sec. = 0; > 3 sec. but < 6 sec. = 1; > 6 sec. = 2), fibrinogen level (> 1 g/L = 0; < 1 g/L = 1). A total score of 5 or more is considered to be compatible with DIC. According to recent observations, the sensitivity and specificity of this scoring system are high (more than 90%) [46]. However, an essential condition for the use of this algorithm is the presence of an underlying disorder known to be associated with DIC [8]. Finally, a scoring system for diagnosing non-overt DIC has recently been proposed by the ISTH Scientific Subcommittee and validated by Toh and Downey who demonstrated its feasibility and prognostic relevance[47].

Figure 1.

Clinical manifestations of coagulation abnormalities in disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Figure 2.

Five-step algorithm for the diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Treatment of DIC

The heterogeneity of the underlying disorders and of the clinical presentations makes the therapeutic approach to DIC particularly difficult [2,48]. Thus, the management of DIC is based on the treatment of the underlying disease, supportive and replacement therapies and the control of coagulation mechanisms. The recent understanding of important pathogenetic mechanisms that may lead to DIC has resulted in novel preventive and therapeutic approaches to patients with DIC [49]. However, in spite of this progress, the therapeutic decisions are still controversial and should be individualized on the basis of the nature of DIC and the severity of the clinical symptoms [50-52]. The treatment for DIC include replacement therapy, anticoagulants, restoration of anticoagulant pathways and other agents [1,2,8]. Most of the clinical studies reported in the next paragraphs were conducted in patients with severe sepsis [53,54], a condition which usually leads to generalized activation of coagulation and thus represents an interesting model for the development of new treatment modalities. Table 3 summarizes the treatment modalities for DIC.

Table 3.

Treatment modalities for disseminated intravascular coagulation.

| 1) Replacement therapy | - Fresh-frozen plasma |

| 2) Anticoagulants | - Unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin |

| - Danaparoid sodium | |

| - Recombinant hirudin | |

| - Recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor | |

| - Recombinant nematode anticoagulant protein c2 | |

| 3) Restoration of anticoagulant pathways | - Antithrombin |

| - Recombinant human activated protein C | |

| 4) Other agents | - Recombinant activated factor VII |

| - Antifibrinolytic agents | |

| - Antiselectin antibodies | |

| - Recombinant interleukin-10 | |

| - Monoclonal antibodies against TNF and CD14 |

a) Replacement therapy

The aim of replacement therapy in DIC is to replace the deficiency due to the consumptionof platelets, coagulation factors and inhibitors in order to prevent or arrest the hemorrhagic episodes [39]. Platelet concentrates and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) were, in the past, used very cautiously because of the fear that they might "feed the fire" and worsen thrombosis in patients with active DIC. However, this fear was not confirmed by clinical practice and nowadays replacement therapy is a mainstay of the treatment of patients with significant bleeding and coagulation parameters compatible with DIC. Transfusion of platelet concentrates at 1–2 U/10 Kg body weight should be considered when the platelet count is less than 20 × 109/L or if there is major bleeding and the platelet count is less than 50 × 109/L. When there is significant DIC-associated bleeding and fibrinogen levels are below 100 mg/dL, the use of FFP, at a dose of 15–20 mL/Kg, is justified. Alternatively, fibrinogen concentrates (total dose 2–3 g) or cryoprecipitates (1 U/10 Kg body weight) may be administered. However, FFP should be preferred to specific coagulation factor concentrates since the former contains all coagulation factors and inhibitors deficient during active DIC and lacks traces of activated coagulation factors, which may instead contaminate the concentrates and exacerbate the coagulation disorder.

b) Anticoagulants

The role of heparin in the treatment of DIC remains controversial [55-62]. In fact, although from a theoretical point of view interruption of the coagulation cascade should be of benefit in patients with active DIC [55], the clinical studies carried out so far have not been conclusive and indeed have often yielded contradictory results [56]. However, on the basis of the few data available in the literature, heparin treatment is probably useful in patients with acute DIC and predominant thromboembolism, such as those with purpura fulminans [2,56]. The use of heparin in chronic DIC is better established and it has been successfully employed in patients with chronic DIC associated with those diseases in which recurrent thrombosis predominates, such as solid tumors, hemangiomas, and dead fetus syndrome [61]. The role of heparin in the treatment of DIC associated with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is another controversy, since some authors support its use whereas other studies failed to demonstrate its efficacy [57-59]. However, the use of heparin in this setting has declined in the last few years thanks to the introduction of all-trans retinoic acid therapy which has led to the reduction of APL-associated coagulopathy. Heparin is usually given at relatively low doses (5–10 U/Kg of body weight per hour) by continuous intravenous infusion and may be switched to subcutaneous injection for long-term outpatient therapy (i.e. for those patients with chronic DIC associated with solid tumors). Alternatively, low-molecular-weight heparin may be used, as supported by the positive results in both experimental and clinical DIC studies [60-63].

Experimental and clinical studies have also shown the potential role of danaparoid sodium, a low molecular weight heparinoid, in the treatment of DIC [64-66].

A newer anticoagulant agent with direct thombin inhibitory activity, recombinant hirudin (r-hirudin) [67,68], was recently shown to be effective in treating DIC in animal studies, although a study of the effect of this thrombin inhibitor in a sheep model of lethal endotoxemia showed no benefit [69]. Preliminary experimental human studies proved that this drug attenuated endotoxin-induced coagulation activation [70].

Since activation of the coagulation cascade during DIC occurs predominantlythrough the extrinsic pathway, theoretically the inhibition of tissue factor should block endotoxin-associated thrombin generation [71]. In vivo experiments in baboon models of lethal DIC showed that TFPI is a potent inhibitor of sepsis-related mortality [72]. De Jonge and colleagues [29] first demonstrated in humans that recombinant TFPI dose-dependently inhibits coagulation activation during endotoxemia. Recombinant TFPI was evaluated in a phase II randomized trial in patients with severe sepsis [73]. Although the study did not have the statistical power to demonstrate a survival benefit, it did show a trend toward a reduction in 28-day all-cause mortality together with an improvement in organ dysfunction in the group of patients treated with the recombinant TFPI. No evidence of a survival advantage was observed in patients with severe sepsis who received recombinant TFPI in a recent phase III large clinical trial[74].

Inhibition of the tissue factor/factor VIIa pathway is an another strategy that has been explored. Moons and colleagues demonstrated the efficacy of recombinant nematode anticoagulant protein c2 (NaPc2), a potent and specific inhibitor of the ternary complex between tissue factor/factor VIIa and factor Xa, in inhibiting coagulation activation in a primate model of sepsis [75]. Other authors have experimented with anti-tissue factor/factor VIIa antibodies in animal models with promising results [23].

c) Restoration of anticoagulant pathways

Since patients with active DIC have an acquired deficiency of coagulation inhibitors, restoration of the physiologic anticoagulation pathways seems to be an appropriate aim of the treatment of DIC [76]. Considering that antithrombin (AT) is the primary inhibitor of circulating thrombin, its use in DIC is certainly rational [77]. Recent studies in animals and humans with severe sepsis have demonstrated that antithrombin also has anti-inflammatory properties (reduction of C-reactive protein and IL-6 levels), which may further justify its utilization during DIC [78,79]. The administration of antithrombin concentrates infused at supraphysiologic concentrations was shown to reduce sepsis-related mortality in animal models [80]. Several small clinical trials have been conducted in humans, mostly in patients with sepsis-related DIC, and have shown beneficial effects in terms of improvement of coagulation parameters and organ function [81,82]. An Italian multicenter, randomized, double-blind study conducted in 1998 by Baudo et al. [83], evaluating the role of antithrombin in patients with sepsis or post-surgical complications, showed a net beneficial effect on survival in those patients receiving the concentrate. These findings were confirmed in 1999 by Levi et al. in their meta-analysis of all so far published human clinical trials of antithrombin treatment of DIC [3]. By contrast, a large randomized, controlled multicenter trial of supraphysiologic doses of AT concentrates conducted in 2144 patients with sepsis and DIC did not show a beneficial effect of antithrombin treatment [84]. However, a retrospective analysis of the same trial showed that the subgroup of patients who did not receive concomitant heparin had a potential benefit from antithrombin III in terms of mortality reduction[85].

Based on the fact that the protein C system is impaired during DIC some authors have investigated the therapeutic efficacy of exogenous administration of this protein in patients with DIC [86-98]. The infusion of activated protein C (APC) concentrates was shown to prevent DIC and mortality in an animal model of sepsis [99]. A study conducted in 1998 on patients with severe sepsis suggested a trend toward improved survival in the group treated with APC [88]. In a dose-ranging clinical trial, 131 patients with sepsis received recombinant human APC by continuous infusion at doses ranging from 12μg/Kg/hour to 30 μg/Kg/hour or placebo [89]. A 40 percent reduction in mortality was observed in those patients who received the higher doses of activated protein C. Similarly, another recent multicenter clinical trial [90] determined that treatment with recombinant human APC, given intravenously at a dose of 24 μg/Kg of body weight per hour, significantly reduced mortality in patients with severe sepsis, in spite of a higher rate of serious bleeding in the APC-treated group. A double-blind randomized trial compared the safety and efficacy of APC and unfractionated heparin in the treatment of DIC and concluded that the former improved DIC, and finally the survival, more efficiently than did heparin [91]. The recently published results of the trial conducted by the Human Recombinant Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Sepsis (PROWESS) Study Group showed a significant reduction in 28-day mortality and a quicker resolution of organ dysfunction in the group of patients with severe sepsis treated with APC [92,93]. These results were confirmed by the ENHANCE trial which also suggested that recombinant APC might be more effective is therapy is started earlier [94]. By contrast, a very recent trial on 2640 patients with severe sepsis and a low risk of death (defined by an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation [APACHE II] score <25 or single organ failure) did not find a statistically significant difference in 28-day mortality rate between the placebo and APC-treated groups[95], suggesting that APC is of benefit only in patients at high risk of death from sepsis.Ongoing studies are focusing on the concomitant use of heparin in patients with DIC who receive activated protein C [8].

d) Other agents

Recombinant factor VII activated (rFVIIa) may be used in patients with severe bleeding who are not responsive to other treatment options. Bolus doses of 60–120 μg/Kg, possibly repeated after 2–6 hours, have been found to be effective in controlling refractory hemorrhagic episodes associated with DIC [100,101]. Antifibrinolytic agents, such as epsilon-aminocaproic acid or tranexamic acid, given intravenously at a dose of 10–15 mg/Kg/h, are occasionally used in patients resistant to replacement therapy who are bleeding profusely or in patients with disease states associated with intense fibrinolysis (prostate cancer, Kasabach-Merrit syndrome, acute promyelocytic leukemia) [102]. However, since these agents are very effective in blocking fibrinolysis, they should not be administered unless heparin has been previously infused in order to block the prothrombotic component of DIC. The use of these drugs in APL has declined in the last few years, given the efficacy of all-trans-retinoic-acid in preventing the majority of the hemorrhagic complications of this malignancy [8].

The advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of DIC have resulted in novel preventive and therapeutic approaches to this disease. Based on the fact that tissue inflammation is a fundamental mechanism in DIC associated with sepsis or major trauma, some researchers have successfully employed the combined blockade of leukocyte/platelet adhesion and coagulation in a murine model by using antiselectin antibodies and heparin and have suggested the potential clinical use of such a strategy [103]. Based on the same rationale, other researchers have demonstrated that the administration of recombinant IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine which may modulate the activation of coagulation, completely abrogated endotoxin-induced effects on coagulation in humans [104]. By contrast, the use of monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrosis factor has shown disappointing or at best modest results in septic patients[105-107]. More recently, Branger and colleagues[108]found that an inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), an important component of intracellular signaling cascades that mediate the inflammatory response to infectious and non-infectious stimuli, attenuated the activation of coagulation, fibrinolysis and endothelial cells during human endotoxemia. Finally, although studies using antibodies against the receptor for bacterial endotoxins (CD14) produced positive results[109], other studies using endotoxin antibodies failed to improve outcome[110,111].

Conclusion

Disseminated intravascular coagulation is a syndrome characterized by systemic intravascular activation of coagulation leading to bleeding (due to depletion of platelets and coagulation factors) and thrombosis(due to widespread deposition of fibrin in the circulation).

The diagnosis of DIC is usually made by a combination of routinely available laboratory tests, using a validated diagnostic algorithm.

In recent years, the mechanisms involved in pathological microvascular fibrin deposition in DIC have become progressively clear, resulting in novel preventive and therapeutic approaches to patients with DIC.

Contributor Information

Massimo Franchini, Email: mfranchini@univr.it.

Giuseppe Lippi, Email: ulippi@tin.it.

Franco Manzato, Email: franco.manzato@ospedalimantova.it.

References

- Bick RL. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Current concepts of etiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;17:149–176. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8588(02)00102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:586–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, de Jonge E, Van der Poll T, ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: state of the art. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:695–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, de Jonge E, Meijers J. The diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood Rev. 2002;16:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0268-960X(02)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammen EF. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Clin Lab Sci. 2000;13:239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: what's new? Crit Care Clin. 2005;21:449–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MJ, Rogers GM. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: clinical and laboratory aspects. Am J Hematol. 1998;59:65–73. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199809)59:1<65::AID-AJH13>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M. Current understanding of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:567–576. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust SN, Heyderman RS, Levin M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and purpura fulminans secondary to infection. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2000;13:179–197. doi: 10.1053/beha.2000.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Treating patients with severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:207–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone RC. Gram-positive organisms and sepsis. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:26–34. doi: 10.1001/archinte.154.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempfle C-E. Coagulation of sepsis. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:213–224. doi: 10.1160/TH03-03-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral A, Opal SM, Vincent J-L. Coagulation in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1032–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumen RM, Hendriks T, van der Ven-Jongekrijg J, et al. Cytokine patterns in patients after major vascular surgery, hemorrhagic shock, and severe blunt trauma. Relation with subsequent adult respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure. Ann Surg. 1993;218:769–776. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199312000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gando S. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in trauma patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27:585–592. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman RW, Rubin RN. Disseminated intravascular coagulation due to malignancy. Semin Oncol. 1990;17:172–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati MB, Falanga A. Pathogenetic mechanisms of thrombosis in malignancy. Acta Haematol. 2001;106:18–24. doi: 10.1159/000046585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbui T, Falanga A. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in acute leukemia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27:593–604. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letsky EA. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;4:623–644. doi: 10.1053/beog.2001.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner CP. The obstetric patient and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Clin Perinatol. 1986;13:705–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T. Advances in the understanding of the pathogenetic pathways of disseminated intravascular coagulation result in more insight in the clinical picture and better management strategies. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27:569–575. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley RA, De La Cadena R, Page JD, et al. The contact system contributes to hypotension but not disseminated intravascular coagulation in lethal bacteremia. In vivo use of a monoclonal anti-factor XII antibody to block contact activation in baboons. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:61–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI116201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemond BJ, Levi M, ten Cate H, et al. Complete inhibition of endotoxin-induced coagulation activation in chimpanzees with a monoclonal Fab fragment against factor VII/VIIa. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. The regulation of natural anticoagulant pathways. Science. 1987;235:1348–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.3029867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz R, Wolf M, Egbring R, Havemann K. The disturbance of hemostasis in septic shock: role of neutrophil elastase and thrombin, effects of antithrombin III and plasma substitution. Eur J Haematol. 1989;43:22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1989.tb01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway EM, Rosenberg RD. Tumor necrosis factor suppresses transcription of the thrombomodulin gene in endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5588–5592. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. Role of coagulation inhibitors in inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust SN, Levi M, Harrison OB, et al. Dysfunction of endothelial protein C activation in severe meningococcal sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:408–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108093450603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge E, Dekkers PE, Creasey AA, et al. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor dose-dependently inhibits coagulation activation without influencing the fibrinolytic and cytokine response during human endotoxemia. Blood. 2000;95:1124–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasey AA, Chang AC, Feigen L, Wun TC, Taylor FB, Jr, Hinshaw LB. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor reduces mortality from Escherichia coli septic shock. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2850–2860. doi: 10.1172/JCI116529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, van der Poll T, de Jonge E, ten Cate H. Relative insufficiency of fibrinolysis in disseminated intravascular coagulation. Sepsis. 2000;3:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Biemond BJ, Levi M, Ten Cate H, et al. Plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor I release during experimental endotoxemia in chimpanzees: effect of interventions in the cytokine and coagulation cascades. Clin Sci. 1995;88:587–594. doi: 10.1042/cs0880587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suffredini AF, Harpel PC, Parrillo JE. Promotion and subsequent inhibition of plasminogen activation after administration of intravenous endotoxin to normal subjects. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1165–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905043201802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans PW, Hibberd ML, Booy R, Daramola O, Hazelzet JA, de Groot R, Levin M. 4G/5G promoter polymorphism in the plasminogen-activator-inhibitor-1 gene and outcome of meningococcal disease. Meningococcal Research Group. Lancet. 1999;354:556–560. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Poll T, de Jonge E, Levi M. Regulatory role of cytokines in disseminated intravascular coagulation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27:639–651. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel M, Okajima K, Uchiba M, Horiuchi S, Okabe H. Activated protein C inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by inhibiting activation of both nuclear factor-kappa B and activator protein-1 in human monocytes. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Poll T, Buller HR, ten Cate H. Activation of coagulation after administration of tumor necrosis factor to normal subjects. N Eng J Med. 1990;322:1622–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006073222302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickles FR, Falanga A. Molecular basis for the relationship between thrombosis and cancer. Thromb Res. 2001;102:V215–224. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(01)00285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bick RL. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: objective clinical and laboratory diagnosis, treatment and assessment of therapeutic response. Semin Thromb Haemost. 1996;22:69–88. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-998993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha E, Paramo JA, Montes R, Panizo C. Acute generalized, widespread bleeding. Diagnosis and management. Haematologica. 1998;83:1024–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Nardella BS, Pechet L. Screening tests of disseminated intravascular coagulation: guidelines for rapid and specific laboratory diagnosis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1777–1780. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200006000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Wakita Y, Nakase T, et al. Increased plasma-soluble fibrin monomer levels in patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Am J Hematol. 1996;51:255–260. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199604)51:4<255::AID-AJH1>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer KA, Rosenberg RD. The pathophysiology of the prethrombotic state in humans: insights gained from studies using markers of hemostatic system activation. Blood. 1987;70:343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Gabazza EC, Asakura H, et al. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC): diagnostic criteria of the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis and of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare for overt DIC. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:17–22. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor FBJ, Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M, Scientific Subcommittee on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1327–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiari K, Meijers JCM, de Jonge E, Levi M. Prospective validation of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2416–2421. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000147769.07699.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh CH, Downey C. Performance and prognostic importance of a new clinical and laboratory scoring system for identifying non-overt disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2005;16:69–74. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200501000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchini M, Manzato F. Update on the treatment of the disseminated intravascular coagulation. Hematology. 2004;9:81–85. doi: 10.1080/1024533042000205504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T. New treatment strategies for disseminated intravascular coagulation based on current understanding of the pathophysiology. Ann Med. 2004;36:41–49. doi: 10.1080/07853890310017251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riewald M, Riess H. Treatment options for clinically recognized disseminated intravascular coagulation. Semin Thromb Haemost. 1998;24:53–59. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T, ten Cate H. Novel approach to the management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:20–24. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T. Therapeutic intervention in disseminated intravascular coagulation: have we made any progress in the last millennium? Blood Rev. 2002;16:29–34. doi: 10.1016/S0268-960X(02)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Poll T. Immunotherapy of sepsis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:165–174. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T. Rationale for restoration of physiological anticoagulant pathways in patients with sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:90–94. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Toit H, Coetzee AR, Chalton DO. Heparin treatment in thrombin-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation in baboon. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:1195–1200. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199109000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein DI. Diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of heparin therapy. Blood. 1982;60:284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle CF, Swisky DM, Freedman L, Hayhoe GFJ. Beneficial effect of heparin in the management of patients with APL. Br J Hematol. 1988;68:283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1988.tb04204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M, Ginsburg D, Mayer R, et al. Is heparin necessary during induction chemotherapy for patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia? Blood. 1987;69:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeghiero F, Avvisati G, Castaman G, Barbui T, Mandelli F. Early deaths and anti-hemorrhagic treatments in acute promyelocytic leukemia. A GIMEMA retrospective study in 268 consecutive patients. Blood. 1990;75:2112–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuragawa N, Hasegawa H, Maki M, Nakagawa M, Nakashima M. Clinical evaluation of low-molecular-weight heparin (FR-860) on disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) – a multicenter co-operative double blind trial in comparison with heparin. Thromb Haemost . 1993;72:475–500. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar G. Idiopathic chronic DIC controlled with low-molecular-weight heparin. Blood Coagul Fibrinol. 1996;7:97–98. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199601000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernerstorfer T, Hollenstein U, Hansen JB. Heparin blunts endotoxin-induced coagulation activation. Circulation. 1999;100:2485–2490. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.25.2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slofstra SH, van't Veer C, Buurman WA, Reitsma PH, ten Cate H, Spek CA. Low molecular weight heparin attenuates multiple organ failure in a murine model of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1365–1370. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000166370.94927.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima Y, Yokota K, Sukamoto T. The effect of danaparoid sodium (danaparoid) on endotoxin-induced experimental disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Thromb Res. 1998;91:221–227. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(98)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontachi Y, Asakura H, Arahata M, et al. Effect of combined therapy of danaparoid sodium and tranexamic acid on chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circ J. 2004;69:1150–1153. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibbotson T, Perry CM. Danaparoid. A review of its use in thromboembolic and coagulation disorders. Drugs. 2002;62:2283–2314. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200262150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz MC, Montes R, Hermida J, Orbe J, Paramo JA, Rocha E. Effect of the administration of recombinant hirudin and/or tissue-plasminogen activator (T-PA) on endotoxin-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation model in rabbits. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1999.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernerstorfer T, Hollenstein U, Hansen JB, et al. Lepirudin blunts endotoxin-induced coagulation activation. Blood. 2000;95:1729–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer ER, Reber G, De Moerloose P, Morel DR. Evaluation of unfractionated heparin and recombinant hirudin on survival in a sustained ovine endotoxin shock model. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2689–2699. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200212000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Asakura H, Jokaji H, et al. Recombinant hirudin for the treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with hematologic malignancy. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1995;6:60–64. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj MS, Bajaj SP. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor: potential therapeutic applications. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham E. Tissue factor inhibition and clinical trials results of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:S31–33. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham E, Reinhart K, Svoboda P. Assessment of the safety of recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor in patients with severe sepsis: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind, dose escalation study. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2081–2089. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200111000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham E, Reinhart K, Demeyer I. Efficacy and safety of Tifacogin (recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor) in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:238–247. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons AH, Peters RJ, Cate H, et al. Recombinant nematode anticoagulant protein c2, a novel inhibitor of tissue factor-factor VIIa activity, abrogates endotoxin-induced coagulation in chimpanzees. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:627–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge E, van der Poll T, Kesecioglu J, Levi M. Anticoagulant factor concentrates in disseminated intravascular coagulation: rationale for use and clinical experience. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27:667–674. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudici D, Baudo F, Palareti G, Ravizza A, Ridolfi L, D'Angelo A. Antithrombin replacement in patients with sepsis and severe shock. Haematologica. 1999;84:452–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima K, Uchiba M. The anti-inflammatory properties of anti-thrombin III: new therapeutic implications. Semin Thromb Haemost. 1998;24:27–32. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inthorn D, Hoffman J, Hartl W, Muhlbayer D, Jochum M. Effect of anti-thrombin III supplementation on inflammatory response in patients with severe sepsis. Shock. 1998;10:90–96. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199808000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler CM, Tang Z, Jacobs HM, Szymanski LM. The suprapharmacological dosing of antithrombin concentrate for Staphylococcus aureus-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation in guinea pigs: substantial reduction in mortality and morbidity. Blood. 1997;89:4393–4401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourrier F, Jourdain M, Tournoys A. Clinical trial results with antithrombin III in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:S38–43. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisele B, Lamy M, Thijs LG, et al. Antithrombin III in patients with severe sepsis: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind multicenter trial plus meta-analysis on all randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials with antithrombin III in severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:663–672. doi: 10.1007/s001340050642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudo F, Caimi TM, de Cataldo F, et al. Antithrombin III (ATIII) replacement therapy in patients with sepsis and/or post-surgical complications: a controlled, double blind, randomized multicenter study. Int Care Med. 1998;24:336–342. doi: 10.1007/s001340050576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren BL, Eid A, Singer P, KyberSept Trial Study Group et al. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286:1869–1878. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienast J, Juers M, Wiedermann CJ, for the KyberSept Investigators et al. Treatment effects of high-dose antithrombon without concomitant heparin in patients with severe sepsis with or without disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluck T, Opal SM. Advances in sepsis therapy. Drugs. 2004;64:837–859. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourrier F. Recombinant human activated protein C in the treatment of severe sepsis: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:S534–541. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000145944.64532.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard GR, Hartman DL, Helterbrand JD, Fisher CJ. Recombinant human activated protein C (rhAPC) produces a trend toward improvement in morbidity and 28-day survival in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1998;27:S4. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard GR, Ely EW, Wright TJ, et al. Safety and dose relationship of recombinant human activated protein C for coagulopathy in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2051–2059. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, Recombinant Human Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) study group et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki N, Matsuda T, Saito H, CTC-111-IM Clinical Research Group et al. A comparative double-blind randomized trial of activated protein C and unfractionated heparin in the treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Int J Hematol. 2002;75:540–547. doi: 10.1007/BF02982120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhainaut JF, Laterre PF, Janes JM, Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) Study Group et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in treatment of severe sepsis patients with multiorgan dysfunction: data from the PROWESS trial. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:894–903. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Angus DC, Artigas A, Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) Study Group et al. Effects of drotrecogin alfa (activated) on organ dysfunction in the PROWESS trial. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:834–840. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000051515.56179.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Bernard GR, Beale R, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) treatment in severe sepsis from global open-label trial ENHANCE: further evidence for survival and safety and implications for early treatment. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2266–2277. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000181729.46010.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham E, Laterre P-F, Garg R, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1332–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T. Recombinant human activated protein C (Xigris) Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56:542–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastores SM. Drotrecogin alfa (activated): a novel therapeutic strategy for severe sepsis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:5–10. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.927.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren HS, Suffredini AF, Eichacker PQ, Munford RS. Risks and benefits of activated protein C treatment for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1027–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb020574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor FB, Chang A, Esmon CT, D'Angelo A, Vigano-D'Angelo S, Blick KE. Protein C prevents the coagulopathic and lethal effects of Escherichia coli infusion in the baboon. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:918–925. doi: 10.1172/JCI112902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo F, Perez F, de la Rubia J, et al. Successful treatment of severe intra-abdominal bleeding associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation using recombinant activated factor VII. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:174–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallah S, Husain A, Nguyen NP. Recombinant activated factor VII in patients with cancer and hemorrhagic disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2004;15:577–582. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvisati G, ten Cate JW, Buller HR, Mandelli F. Tranexamic acid for control of hemorrhage in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Lancet . 1989;2:122–124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KE, Cotter MJ, Stewart BJ. Combined anticoagulant and antiselectin treatments prevent lethal intravascular coagulation. Blood. 2003;101:921–928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajkrt D, van der Poll T, Levi M, et al. Interleukin-10 inhibits activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis during human endotoxemia. Blood. 1997;89:2701–2705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart K, Waheedullah K. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in sepsis: update on clinical trials and lessons learned. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S121–125. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polderman KH, Girbes ARJ. Drug intervention trials in sepsis: divergent results. Lancet. 2004;363:1721–1723. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Carlet J. INTERSEPT: an international, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of monoclonal antibody to human tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with sepsis. International Sepsis Trial Study Group. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1431–1440. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199609000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branger J, van den Blink B, Weijer S, et al. Inhibition of coagulation, fibrinolysis, and endothelial cell activation by a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor during human endotoxemia. Blood. 2003;101:4446–4448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbon A, Meijers JC, Spek CA. Effects of IC14, an anti-CD14 antibody, on coagulation and fibrinolysis during low-grade endotoxemia in humans. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:55–61. doi: 10.1086/346043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler EJ, Fisher CJ, Jr, Sprung CL, et al. Treatment of gram-negative bacteremia and septic shock with HA-1A human monoclonal antibody against endotoxin. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The HA-1A Sepsis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:429–436. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102143240701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey RV, Straube RC, Sanders C, Smith SM, Smith CR. Treatment of septic shock with human monoclonal antibody HA-1A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CHESS Trial Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:1–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-1-199407010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]