Abstract

The α4 integrins (α4β1 and α4β7) are cell surface heterodimers expressed mostly on leukocytes that mediate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesion. A characteristic feature of α4 integrins is that their adhesive activity can be subjected to rapid modulation during the process of cell migration. Herein, we show that transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) rapidly (0.5–5 min) and transiently up-regulated α4 integrin-dependent adhesion of different human leukocyte cell lines and human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) to their ligands vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and connecting segment-1/fibronectin. In addition, TGF-β1 enhanced the α4 integrin-mediated adhesion of PBLs to tumor necrosis factor-α–treated human umbilical vein endothelial cells, indicating the stimulation of α4β1/VCAM-1 interaction. Although TGF-β1 rapidly activated the small GTPase RhoA and the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, enhanced adhesion did not require activation of both signaling molecules. Instead, polymerization of actin cytoskeleton triggered by TGF-β1 was necessary for α4 integrin-dependent up-regulated adhesion, and elevation of intracellular cAMP opposed this up-regulation. Moreover, TGF-β1 further increased cell adhesion mediated by α4 integrins in response to the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1α. These data suggest that TGF-β1 can potentially contribute to cell migration by dynamically regulating cell adhesion mediated by α4 integrins.

INTRODUCTION

The α4 integrins (α4β1 and α4β7) are heterodimer cell adhesion receptors mainly expressed on cells of hematopoietic origin that mediate cell–cell and cell–extracellular matrix interactions (Hynes, 1992; reviewed in Lobb and Hemler, 1994). Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and the alternatively spliced connecting segment-1 (CS-1) region of fibronectin constitute ligands for both integrins, whereas α4β7 can additionally interact with mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (Lobb and Hemler, 1994). α4β1 and α4β7 play key roles in leukocyte recruitment to inflammatory sites and in lymphocyte recirculation, and α4β1 function is required during hematopoiesis in the bone marrow (Springer, 1995; Arroyo et al., 1996; Butcher and Picker, 1996; Butcher et al., 1999).

A characteristic feature of α4 integrins on most leukocytes is that their adhesive activity can be up-regulated by external stimuli, leading to firm attachment. Several chemokines binding to their G protein-coupled receptors, as well as cytokines whose receptors have tyrosine kinase activity, have been previously demonstrated to rapidly and transiently increase α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion (Tanaka et al., 1993; Lévesque et al., 1995; Woldemar Carr et al., 1996; Grabovsky et al., 2000). For instance, the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) up-regulates α4 integrin-mediated lymphocyte, hematopoietic progenitor, and myeloma cell adhesion (Peled et al., 1999; Grabovsky et al., 2000; Hidalgo et al., 2001; Sanz-Rodríguez et al., 2001; Wright et al., 2002). The enhancement in adhesion was shown to be independent of changes in α4 surface expression and was suggested to be the result of variations in the avidity and/or affinity of these integrins for their ligands.

Three mammalians isoforms of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) have been described: TGF-β1, β2, and β3, encoded by different genes (Massagué, 1998). TGF-β1 is a multifunctional cytokine that regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration, and has an important role in tissue recycling and repair (Massagué, 1998; Piek et al., 1999). In addition, TGF-β1 plays a pivotal role in tumor development, eliciting both positive and negative effects in carcinogenesis (Massaguéet al., 2000; Derynck et al., 2001; Wakefield and Roberts, 2002). TGF-β1 is a potent immunosuppresor (Letterio and Roberts, 1998), and its absence causes massive leukocyte infiltration due to increased expression of inflammatory mediators and adhesion molecules whose expression is negatively regulated by TGF-β1 (Shull et al., 1992; Kulkarni et al., 1993). TGF-β1 exerts its biological functions through binding to a heteromeric cell surface complex formed by types I and II TGF-β receptors, which are transmembrane serine/threonine kinases that are required for TGF-β signaling (Derynck and Feng, 1997; Massagué, 1998). Members of the Smad group of proteins mediate signaling from the receptors to the nuclei, acting as intermediates for transcriptional regulation and cell cycle arrest (Derynck et al., 1998; Piek et al., 1999; Massagué and Wotton, 2000; Miyazono et al., 2000).

TGF-β1 controls the synthesis of several integrins (Ignotz and Massagué, 1987; Heino et al., 1989; Parker et al., 1992; Wahl et al., 1993), which is detected after several hours of exposure to the cytokine. On the other hand, TGF-β1 can rapidly (minutes) and independently of Smads, activate several signaling pathways including mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (Hartsough and Mulder, 1995; Hannigan et al., 1998; Hanafusa et al., 1999; Sano et al., 1999) and small GTPases of the Rho subfamily (Mucsi et al., 1996; Bhowmick et al., 2001; Edlund et al., 2002). The latter comprises a group of several proteins that are key regulators of the organization of actin cytoskeleton and play important roles in cell migration (Hall, 1998).

In the present study, we have investigated whether short exposure to TGF-β1 could influence α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion. A potential modulation of this adhesion by TGF-β1 could contribute to lymphocyte extravasation at sites of inflammation, as well as in the trafficking of precursor cells in hematopoietic organs and in secondary lymphoid tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Antibodies

Human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were isolated from buffy coats by Ficol density gradient centrifugation (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), followed by two steps of cell adherence at 37°C onto plastic flasks. Peripheral blood T lymphocytes (PBL-Ts) were purified from PBLs by immunomagnetic negative selection by using a mixture of anti-CD19, anti-CD16, and anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody (mAb), following the method described previously (Sancho et al., 1999). The negatively selected cell population was always >97% positive for CD3 expression, as analyzed by flow cytometry. Isolated cells were washed and resuspended in adhesion medium (RPMI/bovine serum albumin 0.5%) for the assays. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated and cultured as described previously (Dejana et al., 1987). Cells were seeded on tissue culture dishes coated with 0.5% gelatin and grown in Medium 199 (BioWhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (BioWhittaker), 50 μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement (prepared from bovine brain), 100 μg/ml heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and antibiotics, and used up to the second passage. The erythroleukemia K562, myeloid U937, and lymphoid JY, RPMI 8866, and Jurkat human cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (BioWhittaker) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (complete medium). K562 α4 transfectants (Muñoz et al., 1996) were maintained in the same medium containing 1 mg/ml G418 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). The megakaryocytic leukemia-derived human cell line Mo7e was maintained in complete medium and 5 ng/ml rhGM-CSF (R & D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom). The integrin anti-α4 HP1/2, anti-CD19 (Bu12), and the control P3X63 (mAb) were gifts of Dr. Francisco Sánchez-Madrid (Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid, Spain). Anti-CD16 and anti-CD14 were from BD PharMigen (San Diego, CA).

α4 Integrin Ligands and Cell Adhesion Assays

The recombinant FN-H89 fragment of fibronectin, which contains the CS-1 site and lacks the RGD central binding domain, was generated as described previously (Mould et al., 1994). For adhesion to VCAM-1, we used the soluble 7-extracellular domain recombinant human VCAM-1 (sVCAM-1) (R & D Systems). Before the adhesion assays, cell lines were starved for 4 h by incubation in adhesion medium, without detectable loss of viability as determined by trypan blue exclusion. PBLs and PBL-Ts were used directly after their isolation. Cells were labeled for 20 min at 37°C with 2′,7′-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6′)-carboxyfluorescein-acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM) (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands), washed, and resuspended in adhesion medium, followed by treatment with or without inhibitors or antibodies, and finally incubated with rhTGF-β1 (R & D Systems). Cells (5–10 × 104 in 100 μl) were added in triplicates to 96-wells dishes (high-binding; Costar, Cambridge, MA) coated with 2.5 μg/ml FN-H89 or 1–2 μg/ml sVCAM-1. After incubation for 10 min at 37°C, or 2 min after a 15-s centrifugation of plates, unbound cells were removed by three washes with RPMI medium, and adhered cells quantified using a fluorescence analyzer (POLARstar Galaxy; BMG Labtechnologies, Offenburg, Germany). For cell adhesion to HUVECs, monolayers were treated for 10 h with or without 10 ng/ml recombinant human tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Peprotech, London, United Kingdom). Cell adhesion to HUVECs was carried out for 10 min at 37°C, and unbound cells were processed and analyzed as indicated above. In experiments using rhSDF-1α (R & D Systems), the chemokine was incubated with cells in adhesion medium in the presence or in the absence of TGF-β1. Inhibitors used in this study included cytochalasin D, SB 203580, phenylarsine oxide, forskolin, and 8-bromo-cAMP (8-Br-cAMP) (Sigma-Aldrich), PD98059 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), and okadaic acid (Calbiochem). Recombinant C3 transferase was expressed and purified as described previously (Nobes and Hall, 1995). The concentrations used for the different inhibitors were not cytotoxic, as measured in cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry (our unpublished data).

Actin Polymerization Assays

To determine the content of polymerized actin (F-actin) induced by TGF-β1 treatment, 105 cells per condition were permeabilized, fixed, and stained in a single step by the addition of a 2× solution containing 0.5 mg/ml l-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (Sigma-Aldrich), 8% formaldehyde, and 4 U/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-phalloidin (Molecular-Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were incubated at 22°C for 10 min, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and subjected to flow cytometry.

GTPase Activity Assays and MAP Kinase Activation

For GTPase assays, we followed essentially the method reported previously (Robledo et al., 2001). The GST-C21 and GST-PAK-CD fusion proteins were generated as described previously (Sander et al., 1998). To determine the effect of TGF-β1 on RhoA and Rac1 activation, cells (107/condition) were first starved in adhesion medium, followed by incubation at 37°C in the same medium in the absence or in the presence of TGF-β1. Cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and incubated for 15 min at 4°C in 200 μl of lysis buffer (Robledo et al., 2001). Lysates were centrifuged, 15 μl of supernatant was kept for total lysate samples, and the remaining 185 μl was mixed with fusion proteins precoupled to glutathione-agarose beads. The beads and proteins bound to the fusion protein were washed in an excess of lysis buffer, eluted in Laemmli sample buffer, and analyzed for bound Rac1 or RhoA by Western blotting by using monoclonal antibodies against human Rac1 (BD PharMingen) or RhoA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). For p38 MAP kinase activation, 107 cells were starved and subsequently incubated in the presence or in the absence of TGF-β1, followed by solubilization in 1 ml of radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Sanz-Rodríguez et al., 2001). After SDS-PAGE, immunoblots were blocked, incubated with antiphospho-p38 antibodies (New England Biolabs), washed in Tween 20-PBS (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS), and further incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (DAKO A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark). Blots were developed by a chemiluminescence reaction and exposed to radiographic films. After stripping and saturation of nonspecific protein binding sites, the same blots were reprobed with anti-p38 antibodies (New England Biolabs) to test for total p38 protein content.

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of data obtained from two or more experiments each performed in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed Student's t test.

RESULTS

TGF-β1 Rapidly Up-Regulates α4 Integrin-mediated Cell Adhesion

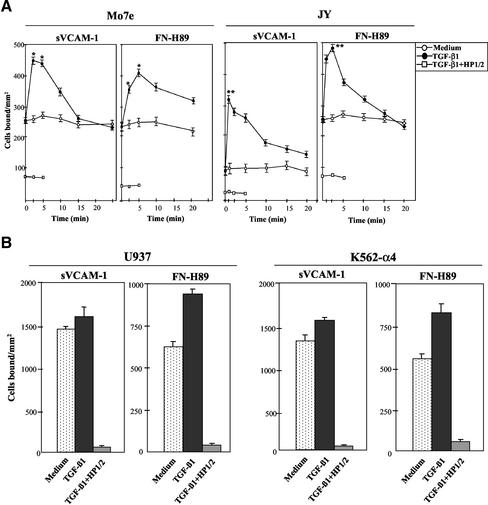

To investigate whether TGF-β1 was capable of influencing α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion we first used the Mo7e and JY human cell lines as models for studies on α4β1- and α4β7-mediated adhesion, respectively, because they exhibit low adhesive efficiencies to α4 integrin ligands (Chan et al., 1992; Lévesque et al., 1995; Hidalgo et al., 2001). We preincubated these cells at 37°C for short periods of time with TGF-β1, followed by their addition for 10 min to wells coated with α4 integrin ligands. TGF-β1 rapidly (2.5–5 min) and transiently up-regulated the attachment of Mo7e cells to sVCAM-1, a soluble form of VCAM-1, and to FN-H89, a CS-1–containing fragment of fibronectin (Figure 1A, left). The anti-α4 HP1/2 mAb blocked the increased adhesion, indicating that α4β1 was mediating the enhancement in cell adhesion. Dose-response experiments showed that concentrations of TGF-β1 between 0.5 and 2 ng/ml were optimal for stimulation of adhesion, whereas higher concentrations were without effect or slightly inhibitory (our unpublished data). JY cells displayed a low capability to attach to sVCAM-1, but TGF-β1 rapidly (1 min) enhanced their adhesion, as well as the attachment to FN-H89, whereas HP1/2 mAb blocked this adhesion (Figure 1A, right), indicating the involvement of α4β7. Additionally, TGF-β1 up-regulated the adhesion to FN-H89 of the α4β7+/α4β1− RPMI 8866 cell line (our unpublished data).

Figure 1.

Modulation of α4 integrin-mediated adhesion by TGF-β1 in human cell lines. BCECF-AM–labeled cells were preincubated for the indicated times (A), or 2.5 min (B), in adhesion medium with or without TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml). Cells were then allowed to adhere for 10 min to sVCAM-1- or FN-H89–coated wells. Some samples were preincubated with the anti-α4 HP1/2 mAb before exposure to TGF-β1. Adhesions were quantified in a fluorescence analyzer and data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from representative results of at least three independent experiments. **Adhesion was significantly stimulated, P < 0.005, or *P < 0.05, according to the Student's two-tailed t test.

In cell lines that express α4β1 and display high basal adhesion levels to α4 integrin ligands (>40% of the input), such as monocytic U937 cells, K562 cells expressing transfected α4 (4 M7 cells; Muñoz et al., 1996) (Figure 1B) and Jurkat T cells (our unpublished data), TGF-β1 had a small or no effect in their α4β1-dependent adhesion. Parental K562 cells did not attach to FN-H89 or sVCAM-1, and addition of TGF-β1 did not induce their attachment to these ligands (our unpublished data).

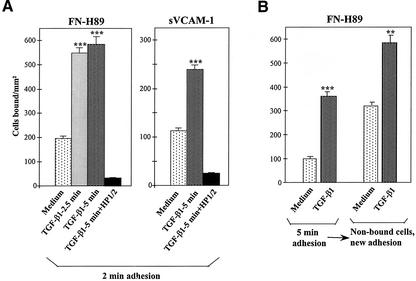

When we shortened the time of adhesion to 2 min after a short spin to place cells faster in contact with α4 integrin ligands, we still detected a notable up-regulation in Mo7e cell adhesion to FN-H89 and sVCAM-1 after 2.5- to 5-min preincubation with TGF-β1 (Figure 2A), suggesting the participation of early signaling events in the increased adhesion. To analyze whether TGF-β1 was selectively targeting a cell population during its modulation of α4 integrin function, we preincubated Mo7e cells for 5 min with TGF-β1 before attachment to FN-H89, and subsequently, nonbound cells were recovered and further preincubated with the cytokine before new adhesion to FN-H89. Analysis of extent of cell adhesion in both cases revealed that TGF-β1 up-regulated the attachment of both the initial and the nonbound cell population (Figure 2B), suggesting that TGF-β1 did not exclusively targeted a determined cell population. When we examined whether FN-H89–attached Mo7e cells that had not been previously in the presence of TGF-β1 were still capable of responding to TGF-β1, we observed no significant changes in the levels of adhesion compared with adhered cells incubated in medium alone (our unpublished data).

Figure 2.

Characterization of α4β1-mediated up-regulation of cell adhesion by TGF-β1. (A) Mo7e cells were labeled with BCECF-AM, preincubated for the indicated times in adhesion medium with or without TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), and allowed to adhere to FN-H89- or sVCAM-1–coated wells for 2 min after a 15-s plate centrifugation. (B) BCECF-labeled Mo7e cells were preincubated for 5 min in adhesion medium in the presence or in the absence of TGF-β1, and allowed to adhere to FN-H89–coated wells for 5 min. Nonbound cells were recovered, again preincubated for 5 min with or without TGF-β1, and allowed to adhere to new FN-H89–coated wells for 10 min. All adhesions were quantified in a fluorescence analyzer and data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from representative results of at least two experiments. ***Adhesion was significantly stimulated, P < 0.001, or **P < 0.005, according to the Student's two-tailed t test.

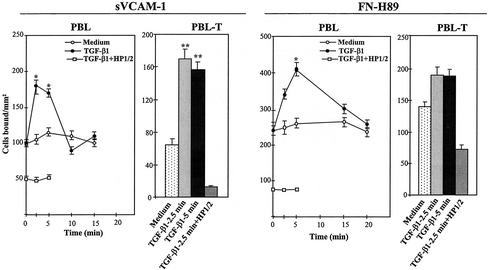

PBLs express cell surface α4 integrins (α4β1 and α4β7) whose adhesive activity has been shown to be the target of modulation by several chemokines (Tanaka et al., 1993; Woldemar Carr et al. 1996; Pachynski et al., 1998; Grabovsky et al., 2000; Wright et al., 2002). Therefore, we used PBLs, as well as PBL-Ts, to study whether TGF-β1 could modulate their attachment to α4 integrin ligands. TGF-β1 rapidly and transiently augmented the attachment of PBLs and PBL-Ts to sVCAM-1, which was blocked by HP1/2 mAb, indicating the involvement of α4 integrins (Figure 3, left). TGF-β1 also increased the adhesion of PBLs and PBL-Ts to FN-H89 but to a lower extent compared with attachment to sVCAM-1 (Figure 3, right).

Figure 3.

Modulation of α4 integrin-mediated adhesion by TGF-β1 in PBL and PBL-T. BCECF-AM–labeled cells were preincubated for the indicated times in adhesion medium in the presence or in the absence of TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml). Cells were then allowed to adhere to sVCAM-1- or FN-H89–coated wells for 10 min. Some samples were preincubated with the anti-α4 HP1/2 mAb before exposure to TGF-β1. Adhesions were quantified in a fluorescence analyzer and data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from representative results of at least three independent experiments. **Adhesion was significantly stimulated, P < 0.005, or *P < 0.05, according to the Student's two-tailed t test.

Control flow cytometry experiments addressed to study whether cell incubation with TGF-β1 altered α4 integrin surface expression showed that incubations up to 25 min with TGF-β1 did not influence the expression of α4 integrins on PBLs and Mo7e cells (our unpublished data).

Because proinflammatory cytokines induce VCAM-1 expression in HUVECs (Osborn et al., 1989), we incubated them with TNF-α and analyzed whether TGF-β1 was capable of modulating the subsequent adhesion of PBLs and PBL-Ts. TGF-β1 did not influence PBL (Figure 4) or PBL-T (our unpublished data) adhesion to resting HUVECs. PBLs and PBL-Ts adhered to higher levels upon TNF-α treatment of HUVECs, and TGF-β1 rapidly up-regulated their α4β1-dependent adhesion, because HP1/2 inhibited the increased adhesion. These results suggest that TGF-β1–triggered up-regulation of PBL and PBL-T adhesion to HUVECs involves at least an increase in α4β1/VCAM-1 interaction.

Figure 4.

Modulation by TGF-β1 of α4 integrin-mediated PBL and PBL-T adhesion to HUVECs. BCECF-AM–labeled cells were preincubated in adhesion medium for the indicated times with or without TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml), and allowed to adhere for 10 min to HUVEC monolayers, which had been pretreated for 10 h in the presence or in the absence of TNF-α. Some samples were preincubated with the anti-α4 HP1/2 mAb before exposure to TGF-β1. Adhesions were quantified in a fluorescence analyzer and data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from representative results out of three independent experiments. **Adhesion was significantly stimulated, P < 0.005, or *P < 0.05, according to the Student's two-tailed t test.

Activation of Rho GTPases and F-Actin Polymerization by TGF-β1: Role in Up-Regulation of α4 Integrin-dependent Cell Adhesion

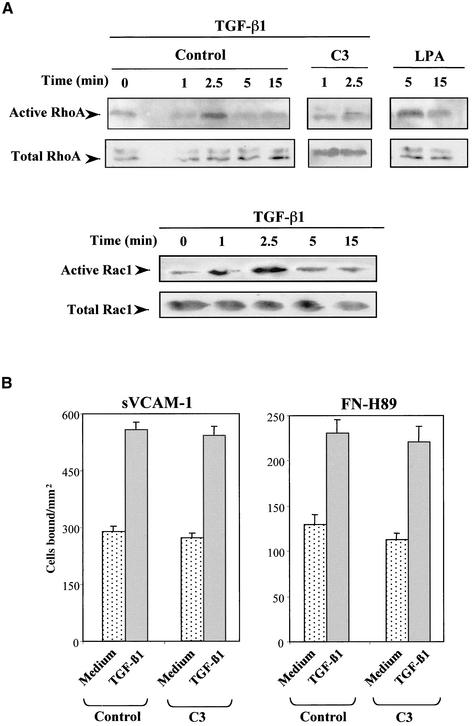

To identify TGF-β1–activated signaling routes that could be involved in the increase in α4 integrin-mediated adhesion, we first tested on Mo7e cells the effect of TGF-β1 on the activation of the small GTPases RhoA and Rac1, key regulators of the organization of actin cytoskeleton (Van Aelst and D'Souza-Schorey, 1997; Hall, 1998), because they are activated by this cytokine in epithelial and fibroblastic cells (Mucsi et al., 1996; Atfi et al., 1997; Bhowmick et al., 2001; Edlund et al., 2002). Mo7e cells were treated for different times with TGF-β1, followed by cell solubilization and incubation of lysates with glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fusion proteins containing domains derived from Rho GTPase targets. For the detection of active RhoA we used GST-C21, which contains the Rho binding domain of the Rho effector Rhotekin, and for active Rac1 the Cdc42/Rac interacting binding domain of the Rac/Cdc42 effector molecule PAK (GST-PAK-CD) was used. SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot by using anti-RhoA or anti-Rac1 antibodies showed that TGF-β1 rapidly and transiently activated RhoA and Rac1 (i.e., GTP-loaded Rho A and Rac1) (Figure 5A). The C3 transferase, an enzyme that specifically ADP-ribosylates and blocks RhoA activation (Aktories et al., 1989), inhibited the activation of Rho A triggered by TGF-β1. Therefore, activation of RhoA and Rac1 by TGF-β1 in Mo7e cells takes place at times when cells become stimulated for increased α4 integrin-dependent adhesion, raising the possibility that downstream signaling activated by these Rho GTPases could participate in the up-regulated adhesion.

Figure 5.

Activation of RhoA by TGF-β1 is not required for up-regulation of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion. (A) TGF-β1 activates RhoA and Rac1. Mo7e cells were preincubated in adhesion medium in the presence or in the absence of C3 exozyme (50 μg/ml, 16 h) and subsequently treated with TGF-β1 (0.5 ng/ml) or with lysophosphatidic acid (5 μM) for the stated times. Cells were solubilized and lysates incubated with glutathione-agarose–bound fusion proteins to detect active RhoA and Rac1. Beads and proteins bound to fusion proteins were eluted in Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed for bound RhoA and Rac1 by Western blot by using anti-RhoA and anti-Rac1 antibodies. Aliquots of the respective lysates served as controls for analyzing total amounts of RhoA and Rac1. (B) Effect of C3 on the up-regulation of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion by TGF-β1. Mo7e cells were exposed to C3 or adhesion medium alone (control). After labeling with BCECF-AM, cells were preincubated for 2.5 min in adhesion medium with or without TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), and allowed to adhere to sVCAM-1– or FN-H89–coated wells for 10 min. Adhesions were quantified in a fluorescence analyzer and data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from representative results of at least two independent experiments.

We used C3 transferase to obtain some insight into a potential participation of RhoA activation in TGF-β1–triggered increase in Mo7e adhesion. C3 did not significantly alter the enhancement in Mo7e adhesion to sVCAM-1 and FN-H89 in response to TGF-β1 (Figure 5B), whereas it substantially inhibited the up-regulation of α4 integrin-mediated cell adhesion in response to the chemokine SDF-1α (Wright et al., 2002; Parmo-Cabañas, Hidalgo, Wright, and Teixido, unpublished data). Moreover, Mo7e treatment with Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of the Rho downstream effector ROCK, did not alter the increase in adhesion to FN-H89 in response to TGF-β1 (our unpublished data). These results suggest that rapid activation of RhoA by TGF-β1 in Mo7e cells is not required for the increase in α4β1-dependent adhesion.

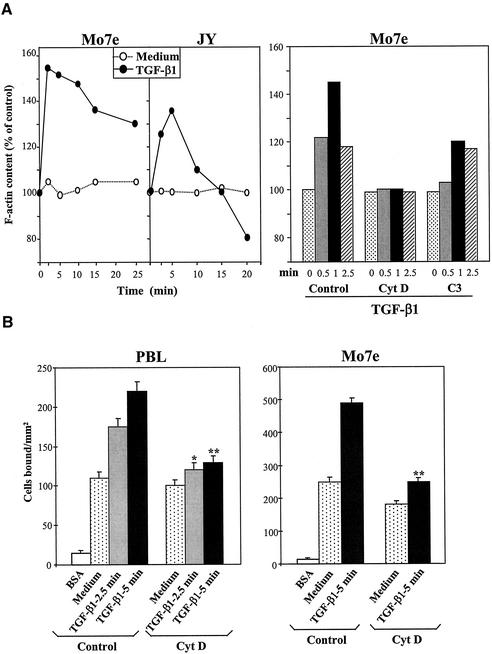

In addition to activating RhoA and Rac1, TGF-β1 rapidly (1–5 min) and transiently triggered F-actin polymerization on Mo7e and JY cells (Figure 6A, left). Cell preincubation with cytochalasin D, an agent that disrupts actin filaments, blocked the enhancement of F-actin polymerization induced by TGF-β1, whereas treatment with C3 resulted in partial inhibition (Figure 6A, right). Preincubation of PBLs and Mo7e cells with cytochalasin D before adding TGF-β1 substantially inhibited the subsequent TGF-β1–stimulated up-regulation of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion (Figure 6B), suggesting that a reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton was implicated in the increased adhesion.

Figure 6.

Role of actin cytoskeleton in up-regulation of α4 integrin-mediated cell adhesion by TGF-β1. (A) Left, cells were incubated for the indicated times with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) or medium alone, stained with FITC-phalloidin, and subjected to flow cytometry. Right, cells were preincubated with cytochalasin D (0.5 μg/ml, 30 min; Cyt D), with C3, or in adhesion medium alone (control), followed by exposure to TGF-β1 for the stated times and processing for flow cytometry as described above. (B) BCECF-AM–labeled cells were treated for 30 min at 37°C in adhesion medium alone (control) or with Cyt D (0.5 μg/ml), preincubated for the stated times in adhesion medium with or without TGF-β1, and allowed to adhere to FN-H89–coated wells for 10 min. Adhesions were quantified in a fluorescence analyzer and data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from representative results of three (PBL) or five (Mo7e) independent experiments. **Adhesion was significantly inhibited, P < 0.005, or *P < 0.05 according to the Student's two-tailed t test.

p38 MAP Kinase Activation by TGF-β1 Is Not Necessary for Enhancement of α4 Integrin-dependent Cell Adhesion

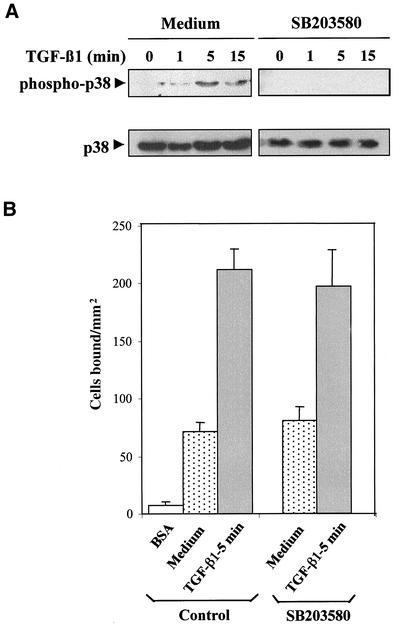

TGF-β1 triggered a rapid (1-min) phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase in Mo7e cells (Figure 7A), which was sustained after 15-min incubation with the cytokine. Preincubation of Mo7e cells with SB 203580, an inhibitor of p38 MAP kinase activation, abrogated the phosphorylation of this kinase induced by TGF-β1, but it did not affect the increase in cell adhesion to FN-H89 in response to TGF-β1 detected (Figure 7B), indicating that activation of p38 MAP kinases is not necessary for TGF-β1–induced increase in adhesion. Moreover, enhancement of α4β1-dependent adhesion of Mo7e cells to FN-H89 and sVCAM-1 by TGF-β1 was not influenced by preincubation with the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 inhibitor PD98058, nor by the protein phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid and phenylarsine oxide (our unpublished data).

Figure 7.

p38 MAP kinase activation by TGF-β1 is not required for enhancement of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion. (A) Mo7e cells were preincubated in adhesion medium for 45 min with or without SB 203580 (13 μM), followed by treatment for the indicated times at 37°C with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml). Cells were solubilized and extracts subjected to immunoblotting by using anti-phospho-p38 MAP kinase antibodies. After stripping and saturating nonspecific protein binding sites, the same blots were reprobed with anti-p38 antibodies to check for total protein content. Blots were developed by a chemiluminescence reaction and exposed to a radiographic film. (B) Mo7e cells were labeled with BCECF-AM, incubated for 45 min in adhesion medium with or without SB 203580 followed by incubation with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml). Cells were subjected to adhesion to FN-H89 for 10 min at 37°C. Adhesions were quantified in a fluorescence analyzer and data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from a representative result of three experiments.

Alterations in Intracellular cAMP Oppose the Up-Regulation of α4 Integrin-dependent Cell Adhesion in Response to TGF-β1

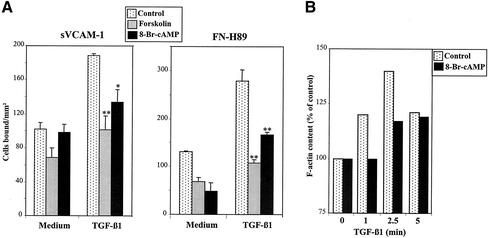

We used forskolin, a direct activator of adenylate cyclase, and 8-Br-cAMP, a cell-permeable cAMP derivative, to test whether alterations in the levels of cAMP could affect the increase in TGF-β1–triggered adhesion mediated by α4 integrins. Pretreatment of Mo7e cells with these two agents substantially inhibited the subsequent up-regulation of cell adhesion to sVCAM-1 and FN-H89 in response to TGF-β1 (Figure 8A), suggesting that elevation of cAMP levels functionally opposed the signaling mechanisms involved in the α4 integrin-dependent enhanced adhesion.

Figure 8.

Alterations in intracellular cAMP oppose the up-regulation of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion in response to TGF-β1. (A) Mo7e cells were labeled with BCECF-AM, incubated for 1 h in adhesion medium without (control) or with forskolin (35 μM) or 8-Br-cAMP (500 μM), followed by incubation for 5 min with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml). Cells were added to wells coated with sVCAM-1 or FN-H89 and subjected to adhesion for 2 min at 37°C after a short spin. Adhesions were quantified in a fluorescence analyzer and data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from a representative result of three independent experiments. **Adhesion was significantly in-hibited, P < 0.005, or *P < 0.05, according to the Student's two-tailed t test. (B) Mo7e cells were treated with or without 8-Br-cAMP as described above followed by incubation with TGF-β1 for the indicated times and staining with FITC-phalloidin and analysis by flow cytometry.

Because Cyt D inhibits both TGF-β1–triggered F-actin polymerization and the increase in α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion, together with the reported data showing that alterations in cAMP levels affected the organization of actin cytoskeleton (Valitutti et al., 1993; Busca et al., 1998; Dong et al., 1998), we tested the effect of 8-Br-cAMP in the induction of F-actin polymerization by TGF-β1. The results showed that 8-Br-cAMP substantially inhibited early (up to 2.5 min) but not late (≥5 min) TGF-β1–activated F-actin polymerization in Mo7e cells (Figure 8B). These data raise the possibility that interference with TGF-β1–stimulated F-actin polymerization by agents that affect intracellular cAMP levels could mediate the inhibitory effects of these agents in up-regulation of α4 integrin-dependent adhesion by TGF-β1.

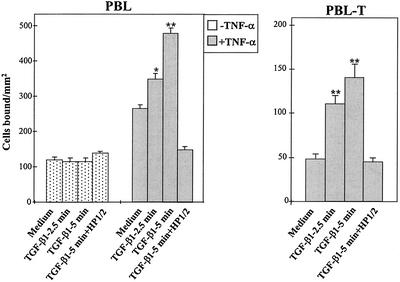

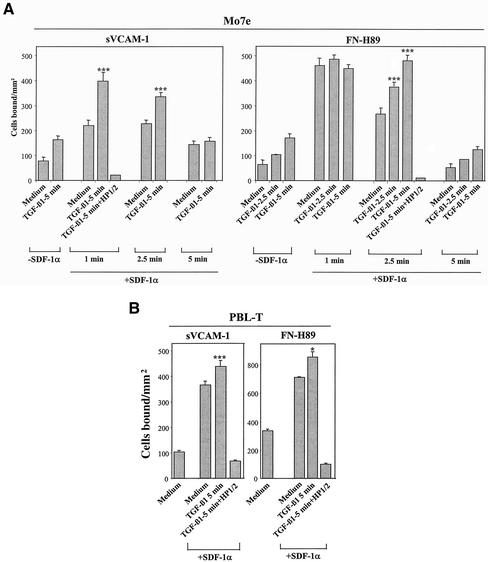

TGF-β1 Further Increases SDF-1α-stimulated α4 Integrin-dependent Cell Adhesion

We previously reported that SDF-1α rapidly and transiently up-regulated α4β1-mediated adhesion of Mo7e cells to sVCAM-1 and FN-H89 (Hidalgo et al., 2001). To study whether TGF-β1 could influence the increase in these adhesions, we incubated Mo7e cells with TGF-β1 in the presence or in the absence of SDF-1α, before subjecting them to adhesion to sVCAM-1 or FN-H89. As expected, cell adhesion was notably up-regulated by SDF-1α, and the presence of TGF-β1 resulted in a substantial further increase in the adhesion that was totally blocked by HP1/2, indicating involvement of α4β1 in the stimulated adhesion (Figure 9A). However, the additive effect of TGF-β1 in cell attachment was not observed when α4 integrin-mediated up-regulation of adhesion by SDF-1α reached ≥30% of the total cellular input in the assay, and was barely detected after the effect of SDF-1α on stimulation of cell adhesion finished. It has also been demonstrated that SDF-1α enhances the adhesion of T lymphocytes to VCAM-1 (Grabovsky et al., 2000). Accordingly, SDF-1α triggered a large up-regulation of T-lymphocyte adhesion to sVCAM-1, and TGF-β1 induced a modest but statistically significant further increase in adhesion, whereas HP1/2 blocked this adhesion (Figure 9B). Furthermore, TGF-β1 up-regulated to a greater extent the enhancement of T-lymphocyte adhesion to FN-H89 in response to SDF-1α. Together, these data indicate that TGF-β1 has an additive effect on the SDF-1α-induced increase in α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion.

Figure 9.

Role of TGF-β1 in SDF-1α–stimulated α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion. Mo7e (A) or PBL-T (B) cells were labeled with BCECF-AM, preincubated for the indicated times with or without TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), in the presence of SDF-1α (150 ng/ml; +SDF-1α) or in adhesion medium alone (−SDF-1α), within the 2.5- or 5-min incubation with TGF-β1. When SDF-1α incubation was longer (5 min) compared with incubation with TGF-β1 (2.5 min), SDF-1α was added before the cytokine. Cells were allowed to adhere for 2 min at 37°C to sVCAM-1– or FN-H89–coated wells after the plate was spun for 15 s. Some samples were preincubated with the anti-α4 HP1/2 mAb before cytokine treatments. Nonbound cells were washed and extent of adhesion measured in a fluorescence analyzer. Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from a representative result of three experiments for each cell type. ***Adhesion was significantly stimulated, P < 0.001, or *P < 0.05, according to the Student's two-tailed t test.

DISCUSSION

A characteristic feature of α4 integrins is that their adhesive activity on leukocytes can be rapidly modulated by external stimuli during the process of cell migration. Several chemokines and cytokines binding to G protein-coupled receptors and tyrosine-kinase receptors, respectively, have been previously demonstrated to trigger rapid and transient up-regulation of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion (Lévesque et al., 1995; Woldemar Carr et al., 1996; Peled et al., 1999; Grabovsky et al., 2000; Hidalgo et al., 2001; Sanz-Rodríguez et al., 2001). In the present study, we show that TGF-β1, a cytokine whose receptors are serine-threonine kinases, is also capable of rapidly and transiently increase α4 integrin-mediated cell adhesion. Incubation with TGF-β1 for short periods of time (0.5–5 min) resulted in an enhancement in the subsequent adhesion of Mo7e and JY cell lines, which express α4β1 and α4β7, respectively, to sVCAM-1 and the CS-1–containing FN-H89 fragment of fibronectin. The up-regulation of α4 integrin-mediated adhesion was detected in adhesion assays as short as 2 min and was independent of changes in α4 cell surface expression, suggesting that rapid TGF-β1–triggered changes in α4 integrin avidity and/or affinity for its ligands were responsible for the augmented adhesion. Cell exposure to TGF-β1 for longer than 30 min, or to concentrations of the cytokine of ≥4 ng/ml, resulted in the absence of adhesion-triggering effects or even produced a slight inhibition in cell attachment to α4 integrin ligands.

Up-regulation of cell adhesion by TGF-β1 was detected in cell lines, such as the mentioned Mo7e and JY, and cells displaying low levels of α4 integrin-dependent adhesion, including whole PBL as well as PBL-T cells. Instead, cell lines showing high adhesion to α4 integrin ligands were refractory to TGF-β1 adhesion modulatory effects. TGF-β1 transiently enhanced the adhesion of both PBLs and PBL-Ts to sVCAM-1, and increased their attachment to TNF-α–treated HUVECs, indicating the activation of the α4β1/VCAM-1 adhesion pathway. TGF-β1 also augmented the adhesion of these cells to FN-H89, but to a lesser extent compared with sVCAM-1.

Enhancement of adhesion by TGF-β1 could either exclusively target a specific cell population expressing α4 integrins activated enough to mediate a basal level of cell attachment and TGF-β1 producing a further activation, or it could target cells expressing nonactive α4 integrins unable to mediate adhesion and TGF-β1 activating them, or else a mixture of both effects. The capability of unbound Mo7e cells recovered from TGF-β1–stimulated adhesions, to respond to this cytokine in a subsequent adhesion suggest that TGF-β1 is not targeting a specific cell population for its adhesion-activating properties. However, whereas ∼30% of Mo7e and JY cells in adhesion assays were capable of enhancing their α4 integrin-dependent adhesion in response to TGF-β1, this percentage was reduced to <10% when using PBLs or PBL-Ts. At this point, we do not know whether a particular lymphocyte subset or most lymphocytes are potentially capable to respond to TGF-β1 by stimulating their α4 integrin-mediated adhesion.

Several important signaling molecules are rapidly activated by TGF-β1, including small GTPases of the Rho family (Hartsough and Mulder, 1995; Mucsi et al., 1996; Bhowmick et al., 2001; Edlund et al., 2002). We show herein that TGF-β1 rapidly and transiently activated RhoA and Rac1 in Mo7e cells, coincident with the times of increased cell adhesion in response to the cytokine. However, activation of RhoA by TGF-β1 was found not to be required for α4 integrin-dependent up-regulation of cell adhesion, because inhibition of RhoA activation by C3 transferase did not influence the enhanced adhesion. In addition to activate RhoA and Rac1, key regulatory molecules of the actin cytoskeleton (Hall, 1998), TGF-β1 triggered a transient increase in cell F-actin polymerization, which was blocked by cytochalasin D and partially inhibited by C3. Moreover, cytochalasin D substantially inhibited TGF-β1–induced increase in α4 integrin-mediated adhesion in PBL and Mo7e cells. These data suggest that a reorganization of actin cytoskeleton in response to TGF-β1 that is independent of RhoA activity might result in an enhancement in the avidity and/or affinity of α4 integrins for their ligands. Because it has been reported that Rac1 activation results in α4β1 clustering in T lymphocytes, leading to increased avidity and up-regulation of T-cell adhesion to fibronectin (D'Souza-Schorey et al., 1998), we cannot exclude that activation of Rac1 could represent a potential mediator response in the enhanced α4 integrin-dependent adhesion by TGF-β1.

The p38 MAP kinase represents an additional signaling molecule rapidly activated by TGF-β1 (Hanafusa et al., 1999; Sano et al., 1999). TGF-β1 triggered a rapid phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase in Mo7e cells, but inhibition of activation of this kinase, as well as that of extracellular signal-regulated kinase MAP kinase, did not influence the up-regulation in α4 integrin-mediated adhesion, suggesting that activation of MAP kinases was not necessary for the TGF-β1–triggered increase in adhesion.

It has been demonstrated previously that cell treatment with agents that increase intracellular cAMP levels can inhibit TGF-β1 actions (Daniel et al., 1987; Grainger et al., 1994; Steiner et al., 1994). We show herein that elevation of intracellular cAMP by incubating cells with the cAMP analog 8-Br-cAMP, or with forskolin, notably reduced the up-regulation of Mo7e cell adhesion to sVCAM-1 and FN-H89 in response to TGF-β1, and inhibited TGF-β1–induced increase in F-actin polymerization, indicating that these agents were altering at some point the signaling leading to actin-regulated enhanced adhesion. Altogether, these results suggest that TGF-β1 might promote a rapid and actin-controlled spatial reorganization of α4 integrins in the plasma membrane, potentially leading to the clustering of these integrins, and increased cell adhesion as a result of an enhancement in the avidity for their ligands. It is possible that in the absence of stimulation, actin fibers might hold α4 integrins in an inactive form, and reorganization of actin by TGF-β1 could contribute to a transient release toward an active integrin conformation, which could reflect the mentioned clustering, but also to a conformation displaying higher affinity for their ligands.

Several chemokines are potent activators of lymphocyte adhesion involving α4 integrin adhesive activity (Tanaka et al., 1993; Woldemar Carr et al., 1996; Pachynski et al., 1998; Grabovsky et al., 2000; Wright et al., 2002). For instance, SDF-1α bound to the surface of endothelial cells can interact with CXCR4-bearing lymphocytes in the bloodstream and trigger their α4β1-dependent firm adhesion, which enables them to resist blood shear flow, before initiating transendothelial migration (Grabovsky et al., 2000). TGF-β1 is expressed by endothelial cells and, similarly to SDF-1α, it can bind to proteoglycans and extracellular matrix proteins (Fava and McClure, 1987; Hannan et al., 1988; Antonelli-Orlidge et al., 1989; Murphy-Ullrich et al., 1992; Butzow et al., 1993) and therefore could also be displayed by these molecules on endothelial cells in the lumen of blood vessels, as well as in the underlying extracellular matrices. Consequently, lymphocyte extravasation could represent a process potentially modulated by TGF-β1 by its transient up-regulation of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion. Additionally, we show herein that TGF-β1 modestly, but significantly further augmented the number of PBL-T cells adhered to α4 integrin ligands during rapid SDF-1α activation of this adhesion. The additional enhancement in adhesion to both sVCAM-1 and FN-H89 was much larger when we used Mo7e cells, indicating the likelihood of TGF-β1 additive effects to SDF-1α in the modulation of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion. It is clear from these results that, compared with SDF-1α and possibly with other chemokines, TGF-β1 contribution to increase in lymphocyte adhesion mediated by α4 integrins is low. However, the results presented herein on time kinetics of activation of this adhesion by SDF-1α and TGF-β1 raises the possibility that this cytokine might prolong SDF-1α–activated adhesion and hence contribute to cell migration.

In addition to its potential contribution to lymphocyte extravasation at sites of inflammation, rapid activation of α4β1-dependent adhesion by TGF-β1 might also have a role in the trafficking of precursor cells in hematopoietic organs, where cell motility between different niches is thought to occur, allowing controlled maturation responses. Moreover, modulation by TGF-β1 of lymphocyte α4β7-dependent adhesion within secondary lymphoid organs could also contribute to their motility during lymphocyte immune surveillance functions. All the above-mentioned processes require a rapid and dynamic modulation of α4 integrin-dependent adhesion, and hence, TGF-β1 together with chemokines could mediate controlled adhesion/detachment cycles allowing cell migration.

A previous work reported that TGF-β1 was capable of enhancing T-lymphocyte attachment to whole fibronectin and that TGF-β1 down-modulated SDF-1α–triggered increase in adhesion (Brill et al., 2001). A possible explanation for the discrepancy with our results is that we used much shorter times (maximum 7 min) of cell exposure to SDF-1α and TGF-β1, whereas in the other case T-lymphocyte adhesion was measured after 1 h of incubation with both stimuli. As mentioned above, we have observed that long incubations with TGF-β1 results in a subsequent reduction in α4 integrin-mediated cell adhesion that could also explain these different results.

The present data indicate that different extracellular stimuli acting through different types of membrane receptors, such as TGF-β1 receptors and CXCR4, are capable of triggering the activity of the same adhesion molecules, although with different kinetics and potencies. In addition, the signaling pathways activated by these different stimuli have common molecular points, including Rho GTPases and MAP kinases, as well as common cell responses, such as polymerization of the actin cytoskeleton. Interfering with the induction of actin polymerization triggered by TGF-β1 and SDF-1α results in both cases in the inhibition of up-regulation of α4 integrin-mediated cell adhesion, indicating that the actin reorganization response might represent a common mechanism for enhanced avidity/affinity of α4 integrins for their ligands. Collectively, the results presented herein suggest that rapid modulation of α4 integrin-dependent cell adhesion by TGF-β1 could represent an additional stimulus contributing to the process of cell migration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Francisco Sánchez-Madrid, Santiago Lamas, and Angel Corbí for providing reagents. Natalia Wright is acknowledged for preparation of fusion proteins. This work was supported by grant SAF99-0057 from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología. R.A.B. is a recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from CSIC-Glaxo Wellcome. F.S.-R. and A.H. were recipients of predoctoral fellowships from Fundación Ramón Areces and the Comunidad de Madrid, respectively. M.M.R. was a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Comunidad de Madrid.

Abbreviations used:

- CS-1

connecting segment-1 of fibronectin

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- SDF-1α

stromal cell-derived factor-1α

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–05–0275. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–05–0275.

REFERENCES

- Aktories K, Braunn U, Rosener S, Just I, Hall A. The rho gene product expressed in E. coli is a substrate of botulinum ADP-ribosyltransferase C3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;158:209–213. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli-Orlidge A, Saunders KB, Smith SR, D'Amore PA. An activated form of transforming growth factor β is produced by cocultures of endothelial cells and pericytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4544–4548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo AG, Yang JT, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Differential requirements for α4 integrins during fetal and adult hematopoiesis. Cell. 1996;85:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atfi A, Djelloul S, Chastre E, Davis R, Gespach C. Evidence for a role of Rho-like GTPases and stress-activated protein knase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK) in transforming growth factor β-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1429–1432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick NA, Ghiassi M, Bakin A, Aakre M, Lundquist CA, Engel ME, Arteaga CL, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor-β1 mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation through a RhoA-dependent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:27–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill A, Franitza S, Lider O, Hershkoviz R. Regulation of T-cell interaction with fibronectin by transforming growth factor-β is associated with altered Pyk2 phosphorylation. Immunology. 2001;104:149–156. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busca R, Bertolotto C, Abbe P, Englaro W, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Boquet P, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R. Inhibition of Rho is required for cAMP-induced melanoma cell differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1367–1378. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher EC, Williams M, Youngman K, Rott L, Briskin M. Lymphocyte trafficking and regional immunity. Adv Immunol. 1999;72:209–253. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butzow R, Fukushima D, Twardzik DR, Ruoslahti E. A 60-kD protein mediates the binding of transforming growth factor-β to cell surface and extracellular matrix proteoglycans. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:721–727. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan BMC, Elices MJ, Murphy E, Hemler ME. Adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and fibronectin. Comparison of α4β1 (VLA-4) and α4β7 on the human B cell line JY. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8366–8370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel TO, Gibbs VC, Milfay DF, Williams LT. Agents that increase cAMP accumulation block endothelial c-sis induction by thrombin and transforming growth factor-β. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:11893–11896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejana E, Colella S, Languino LR, Balconi G, Corbascio GC, Marchisio PC. Fibrinogen induces adhesion, spreading and microfilament organization of human endothelial cells in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1403–1411. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.5.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-β signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2001;29:117–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Feng XH. TGF-β receptor signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1333:F105–F150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Shang Y, Feng XH. Smads transcriptional activators of TGF-β responses. Cell. 1998;11:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong JM, Leung T, Manser E, Lim L. cAMP-induced morphological changes are counteracted by the activated RhoA small GTPase and the Rho kinase ROKα. J Biol Chem. 1998;28:22554–22562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Schorey C, Boettner B, Van Aelst L. Rac regulates integrin-mediated spreading and increased adhesion of T lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3936–3946. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund S, Landstrom M, Heildin CH, Aspenstrom P. Transforming growth factor-β-induced mobilization of actin cytoskeleton requires signaling by small GTPases Cdc42 and RhoA. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:902–914. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-08-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava RA, McClure DB. Fibronectin-associated transforming growth factor. J Cell Physiol. 1987;131:184–189. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabovsky V, S, et al. Subsecond induction of α4 clustering by immobilized chemokines stimulates leukocyte tethering and rolling on endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 under flow conditions. J Exp Med. 2000;192:495–505. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger DJ, Kemp RP, Witchell CM, Weissberg PL, Metcalfe JC. Transforming growth factor β decreases the rate of proliferation of rat vascular smooth muscle cells by extending the G2 phase of the cell cycle and delays the rise in cyclic AMP before entry into M phase. Biochem J. 1994;299:227–235. doi: 10.1042/bj2990227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanafusa H, Ninomiya-Tsuji M, Masuyama N, Nishita M, Fujisawa J, Shibuya H, Matsumoto K, Nishida E. Involvement of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in transforming growth factor-β-induced gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27161–27167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan RL, Kourembanas S, Flanders KC, Rogelj SJ, Roberts AB, Faller DV, Klagsbrun M. Endothelial cells synthesize basic fibroblast growth factor and transforming growth factor β. Growth Factors. 1988;1:7–17. doi: 10.3109/08977198809000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan M, Zhan L, Ai Y, Huang C-K. The role of p38 MAP kinase in TGF-β1-induced signal transduction in human neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:55–58. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartsough MT, Mulder KM. Transforming growth factor β activation of p44mapk in proliferating cultures of epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7117–712416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heino J, Ignotz RA, Hemler ME, Crouse C, Massagué J. Regulation of cell adhesion receptors by transforming growth factor-β. Concomitant regulation of integrins that share a common β 1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:380–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo A, Sanz-Rodríguez F, Rodríguez-Fernández J-L, Albella R, Blaya C, Wright N, Prósper F, Cabañas C, Gutierrez-Ramos J-C, Teixidó J. The chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1α modulates VLA-4 integrin-dependent adhesion to fibronectin and VCAM-1 on bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:345–355. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00668-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignotz RA, Massagué J. Cell adhesion protein receptors as targets for transforming growth factor-β action. Cell. 1987;51:189–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni AB, Huh C-G, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Ward JW, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor β1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letterio JJ, Roberts AB. Regulation of immune responses by TGF-β. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque J-P, Leavesley DI, Niutta S, Vadas M, Simmons PJ. Cytokines increase human hemopoietic cell adhesiveness by activation of very late antigen (VLA)-4 and VLA-5 integrins. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1805–1815. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb RR, Hemler ME. The pathophysiologic role of α4 integrins in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1722–1728. doi: 10.1172/JCI117519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. TGF-β signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFβ signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J, Wotton D. Transcriptional control by the TGF-β/Smad signaling system. EMBO J. 2000;19:1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, ten Dijke P, Heldin CH. TGF-β signaling by Smad proteins. Adv Immunol. 2000;75:115–157. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(00)75003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mould AP, Askari JA, Craig SE, Garrat AN, Clements J, Humphries MJ. Integrin α4β1-mediated melanoma cell adhesion and migration on vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and the alternatively spliced IIICS region of fibronectin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27224–27230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucsi I, Skorecki KL, Goldberg HJ. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and the small GTP-binding protein, Rac, contribute to the effects of transforming growth factor-βl on gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16567–16572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz M, Serrador J, Sánchez-Madrid F, Teixidó J. A region of the integrin VLAα4 subunit involved in homotypic cell aggregation and in fibronectin but not VCAM-1 binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2696–2702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Schultz-Cherry S, Hook M. Transforming growth factor-β complexes with thrombospondin. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:181–188. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, rac and cdc42 regulate the assembly of multi-molecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn L, Hession C, Tizard R, Vassallo C, Luhowskyj S, Chi-Rosso G, Lobb R. Direct expression cloning of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, a cytokine-induced endothelial protein that binds to lymphocytes. Cell. 1989;59:1203–1211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachynski RK, Wu SW, Gunn MD, Erle DJ. Secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine (SLC) stimulates integrin α4β7-mediated adhesion of lymphocytes to mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) under flow. J Immunol. 1998;161:952–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker CM, Cepek KL, Russell GJ, Shaw SK, Posnett DN, Schwarting R, Brenner MB. A family of β7 integrins on human mucosal lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1924–1928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled A, Grabovsky V, Habler L, Sandbank J, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Petit I, Ben-Hur H, Lapidot T, Alon R. The chemokine SDF-1 stimulates integrin-mediated arrest of CD34+ cells on vascular endothelium under shear flow. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1199–1211. doi: 10.1172/JCI7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piek E, Heldin CH, Ten Dijke P. Specificity, diversity, and regulation in TGF-β superfamily signaling. FASEB J. 1999;12:2105–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robledo MM, Bartolomé RA, Longo N, Rodríguez-Frade JM, Mellado M, Longo I, van Muijen GNP, Sánchez-Mateos P, Teixidó J. Expression of functional chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CXCR4 on human melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45098–45105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho D, Yanez-Mo M, Tejedor R, Sánchez-Madrid F. Activation of peripheral blood T cells by interaction and migration through endothelium: role of lymphocyte function antigen-1/intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and interkeukin-15. Blood. 1999;93:886–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander EE, van Delft S, ten Klooster JP, Reid T, van der Kamen RA, Michiels F, Collard JG. Matrix-dependent Tiam1/Rac signaling in epithelial cells promotes either cell-cell adhesion or cell migration and is regulated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1385–1398. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano Y, Harada J, Tashiro S, Gotoh-Mandeville R, Maekawa T, Ishii S. ATF-2 is a common nuclear target of Smad and TAK1 pathways in transforming growth factor-β signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8949–8957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Rodríguez F, Hidalgo A, Teixidó J. Chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1α modulates VLA-4 integrin-mediated multiple myeloma cell adhesion to CS-1/fibronectin and VCAM-1. Blood. 2001;97:346–351. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull MM, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer TA. Traffic signals on endothelium for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:827–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.004143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner MS, Wand GS, Barrack ER. Effects of transforming growth factor β 1 on the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP pathway in prostate cancer. Growth Factors. 1994;11:283–290. doi: 10.3109/08977199409011001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Adams DH, Hubscher S, Hirano H, Siebenlist U, Shaw S. T-cell adhesion induced by proteoglycan-immobilized cytokine MIP-1. Nature. 1993;361:78–82. doi: 10.1038/361079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valitutti S, Dessing M, Lanzavecchia A. Role of cAMP in regulating cytotoxic T lymphocyte adhesion and motility. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:790–795. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Aelst L, D'Souza-Schorey C. Rho GTPases and signaling networks. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2295–2322. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl SM, Allen JB, Weeks BS, Wong HL, Klotman PE. Transforming growth factor β enhances integrin expression and type IV collagenase secretion in human monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4577–4581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield LM, Roberts AB. TGF-β signaling: positive and negative effects on tumorigenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:22–29. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woldemar Carr M, Alon R, Springer TA. The C-C chemokine MCP-1 differentially modulates the avidity of β1 and β2 integrins on T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;4:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80682-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright N, Hidalgo A, Rodríguez-Frade J-M, Soriano SF, Mellado M, Parmo-Cabañas M, Briskin MJ, Teixidó J. The chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1α modulates 47 integrin-mediated lymphocyte adhesion to MAdCAM-1 and fibronectin. J Immunol. 2002;168:5268–5277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]