Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the national distribution of prolonged waiting for elective day case and inpatient surgery, and to examine associations of prolonged waiting with markers of NHS capacity, activity in the independent sector, and need.

Setting

NHS hospital trusts in England.

Population

People waiting for elective treatment in the specialties of general surgery; ear, nose and throat surgery; ophthalmic surgery; and trauma and orthopaedic surgery.

Main outcome measure

Numbers of people waiting six months or longer (prolonged waiting). Characteristics of trusts with large numbers waiting six months or longer were examined by using logistic regression.

Results

The distribution of numbers of people waiting for day case or elective surgery in all the specialties examined was highly positively skewed. Between 52% and 83% of patients waiting longer than six months in the specialties studied were found in one quarter of trusts, which in turn contributed 23-45% of the national throughput specific to the specialty. In general, there was little evidence to show that capacity (measured by numbers of operating theatres, dedicated day case theatres, available beds, and bed occupancy rate) or independent sector activity were associated with prolonged waiting, although exceptions were noted for individual specialties. There was consistent evidence showing an increase in prolonged waiting, with increased numbers of anaesthetists across all specialties and with increased bed occupancy rates for ear, nose and throat surgery. Markers of greater need for health care, such as deprivation score and rate of limiting long term illness, were inversely associated with prolonged waiting.

Conclusion

In most instances, substantial numbers of patients waiting unacceptably long periods for elective surgery were limited to a small number of hospitals. Little and inconsistent support was found for associations of prolonged waiting with markers of capacity, independent sector activity, or need in the surgical specialties examined.

What is already known about this topic

Many patients wait unacceptably long times for NHS surgery

The size of waiting lists is of little relevance to understanding access to treatment

Evidence is scant for the common assumption that the waiting problem arises from a global mismatch between supply and demand and can be solved either by greater rationing or by increasing NHS capacity

What this study adds

Long waiting lists are not an indication of a general failure of the NHS

One quarter of hospital trusts contribute between half and four fifths of the patients waiting six months or longer

Measures of capacity (such as beds, operating theatres, doctors) and independent sector activity are not generally associated with prolonged waiting

Introduction

Waiting lists have a central place in the experience and perception of health care in the NHS in the United Kingdom, although they are also a feature of publicly funded health systems in other countries.1–7 The phenomenon of waiting lists has changed little over the 50 year history of the NHS despite the high political profile of attempts to ameliorate it.8 Long waiting lists are clearly a form of rationing and may imply that rationing is a necessary response to an overall disparity between demand and supply in a publicly funded health system that is free at the point of access. It may be misleading to interpret specific failures in health care in terms of economists' conventional assumption of a global mismatch between demand and supply.9 In specific areas of failed supply, particularly total hip replacement and cataract extraction, it seems that empirically measured potential demand is within the capacity of the NHS.10,11

Waiting lists include a continuum of predicaments from, at one extreme, patients whose treatments are scheduled within a reasonable period, to, at the other extreme, patients having to wait so long that their access to treatment becomes nominal. In this study we are interested in unacceptable waiting rather than legitimate scheduling. We examined the distribution of patients who are subjected to long periods of waiting for elective surgical inpatient and day case treatment—firstly, to determine whether this is a generalised expression of demand exceeding supply and, secondly, to seek explanations for the patterns that emerge in terms of capacity in the NHS, activity in the independent sector, characteristics of trusts, and need for health care (see box).

Methods

The waiting list data are for England during the quarter ending December 1999 (KH07 quarterly returns, Department of Health). The waiting time for each patient for day case or inpatient elective surgery in the specialties of general surgery; ear, nose, and throat surgery; ophthalmic surgery; and trauma and orthopaedic surgery, was classified as less than six months or six months and longer, on the basis that waiting six months or longer for surgery represents an unacceptable denial of access to treatment. A maximum wait of six months is a target (by end 2005) performance indicator in the NHS Plan.12

Factors associated with prolonged waiting

We used routine data obtained from the Department of Health and the Office for National Statistics and measured capacity of trusts by using as variables total numbers of consultants in the surgical specialty and of consultant anaesthetists on 30 September 1999 (DoH census of medical and dental workforce), total numbers of operating theatres, numbers of dedicated theatres for day cases, average daily numbers of available beds (occupied and unoccupied), occupied beds and bed occupancy rate (occupied beds/available beds; from KH03 returns). We measured independent sector activity by the numbers of private hospitals and clinics and of registered beds in private hospitals and clinics, in each trust's health authority, excluding private nursing homes (DoH community care statistics for private nursing homes, hospitals, and clinics). We measured need for health care by the proportion of the population older than 65 in the health authority in which the trust was located, Jarman score, standardised mortality ratio, and levels of long term limiting illness in the trust's health authority (Office for National Statistics, 1991 census). We also obtained data from the internet on whether the trust was a teaching (university) hospital defined according to a classification used by the Department of Health and whether or not the trust received three stars (the highest rated trusts) in the performance ratings exercise.13

Factors considered as contributing to prolonged waiting and included in explanatory models

Throughput: Speciality specific number of finished consultant episodes per year

Capacity: Numbers of consultants and anaesthetists per 100 beds and of operating theatres, average daily numbers of available beds, bed occupancy rate

Intensity of activity in independent sector (per health authority): Numbers of private hospitals and clinics and of beds in private hospitals and clinics

Population size of the trust's health authority

Need (per health authority): Rate of long term limiting illness, proportion of the population >65, Jarman score, standardised mortality ratio

Characteristics of trusts: Teaching hospital status, performance rating

We had no routine or accepted measure of the specialty specific catchment population in each trust that was at risk of prolonged waiting. We used trust throughput, in terms of finished consultant episodes (in thousands) per year for each specialty (KP70 returns), as our measure of the population at risk.

Descriptive analysis

Firstly, we charted the specialty specific distribution of the numbers of people in each trust waiting six months or longer. Secondly, we computed the contribution made by trusts forming the upper fourth of numbers of patients whose waits were prolonged to the total numbers waiting six months or longer. Thirdly, we expressed the number of patients waiting six months or longer as a percentage of the national throughput for day case and inpatient surgery in each specialty (measured by total number of finished consultant episodes). Fourthly, we mapped the geographical distribution of trusts with the most patients with prolonged waits (top 25% of the distribution) in 1999 in relation to all other trusts, using boundary material and ArcView GIS 3.2 (ESRI, 1999) to create maps.

Statistical analysis

To examine associations between individual variables reflecting capacity, independent sector activity, need, and characteristics of trusts we used correlation coefficients. To investigate the characteristics of those hospital trusts with the highest numbers of patients whose waits were prolonged, we used logistic regression to compare trusts forming the upper fourth of numbers of patients whose waits were prolonged with the lower three fourths. Explanatory variables were grouped into thirds so that estimated odds ratios are per third increase in each variable.

Simple models controlled for the specialty specific numbers of finished consultant episodes per trust and the population of the trust's health authority (Office for National Statistics, vital statistics). Multivariable models controlled additionally for numbers of available beds, anaesthetists, specialty specific surgeons, private beds, proportion older than 65 in each trust's health authority, Jarman score, standardised mortality ratio, and rate of limiting long term illness. We repeated these analyses by comparing trusts with the upper tenth of patients with prolonged waits with the rest and comparing the top fourth waiting nine months or longer and 12 months or longer with the lower three fourths.

We also investigated associations with rates of prolonged waiting by using negative binomial regression, an extension of Poisson regression that allows for variation in rates between trusts.14 The outcome in these analyses was the rate of waiting, in which the numerator was the number of people waiting six months or longer in a particular specialty and the denominator (offset) the specialty specific numbers of finished consultant episodes for each trust. To assess effect modification by the throughput of the hospital, we categorised each hospital as high or low throughput (corresponding to above or below the median number of finished consultant episodes) and examined interactions with each explanatory variable, using likelihood ratio tests. We correlated rates of prolonged waiting between specialties, to investigate whether the same trusts have high rates of prolonged waiting. We used Stata 7.0 for these analyses.

Results

Distribution of waiting

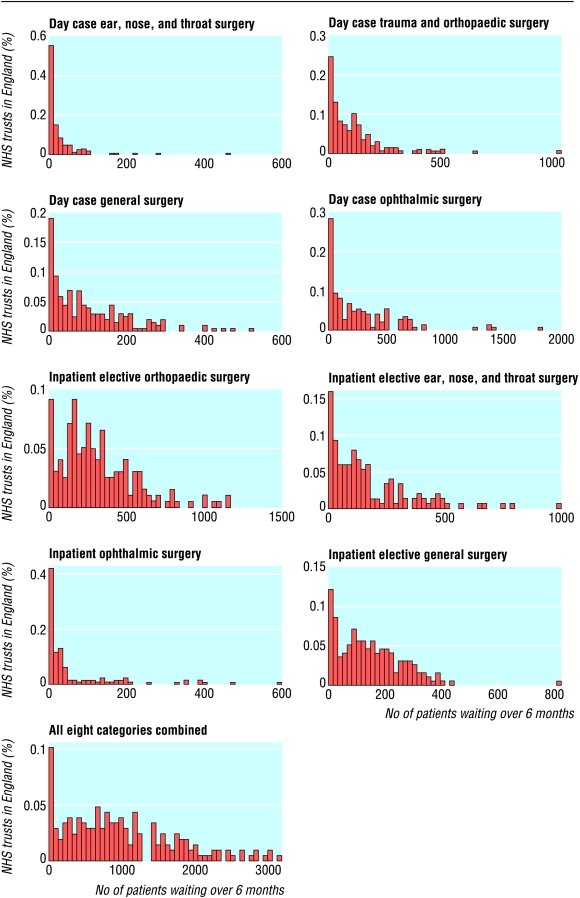

The distribution of numbers of people waiting for day case or elective surgery in all specialties examined is highly skewed (fig 1). This implies that in most instances substantial numbers of patients waiting longer than six months are restricted to a relatively small proportion of trusts. The absolute numbers of people waiting longer than six months were strongly correlated with rates of waiting longer than six months per specialty specific finished consultant episode (Spearman's rank correlation coefficients 0.83-0.94).

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients waiting longer than six months in NHS trusts in England, December 1999

Altogether 718 284 patients were waiting for day case or inpatient elective surgery in England during the quarter ending December 1999 (table 1). For day cases, 18-28% of patients had waited longer than six months (prolonged waits). The corresponding figures for inpatient surgery were 29-40%. Specialties vary in the extent to which patients with prolonged waits represent a substantial proportion of their throughput; in most specialties the numbers waiting prolonged periods are small in relation to national throughput (3-16%). Between 52% and 83% of patients with prolonged waits were found in 25% of trusts (trusts in the upper fourth of the distribution of patients with prolonged waits) who contributed to 23-45% of national throughput (table 1).

Table 1.

Specialty specific distribution of numbers of patients waiting for elective surgery in England, 1 October-31 December 1999

| Specialty

|

No of trusts

|

Total No waiting

|

Total No (%) waiting ⩾6 months

|

Overall national throughput*

|

Patients waiting ⩾6 months as % of national throughput*

|

% contribution of upper fourth of trusts to

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No waiting ⩾6 months in England†

|

National throughput

|

|||||||

| General surgery: | ||||||||

| Day cases | 204 | 109 818 | 20 813 (19) | 445 705 | 5 | 60 | 30 | |

| Inpatients | 197 | 99 147 | 28 609 (29) | 925 412 | 3 | 52 | 32 | |

| Trauma and orthopaedic surgery: | ||||||||

| Day cases | 207 | 88 344 | 22 562 (26) | 181 684 | 12 | 63 | 29 | |

| Inpatients | 197 | 154 835 | 61 399 (40) | 588 623 | 10 | 52 | 36 | |

| Ear, nose, and throat surgery: | ||||||||

| Day cases | 165 | 23 566 | 4 356 (18) | 110 940 | 4 | 80 | 23 | |

| Inpatients | 150 | 79 274 | 25 525 (32) | 249 758 | 10 | 63 | 31 | |

| Ophthalmic surgery: | ||||||||

| Day cases | 149 | 138 659 | 39 174 (28) | 238 153 | 16 | 67 | 42 | |

| Inpatients | 128 | 24 641 | 8 121 (33) | 119 528 | 7 | 83 | 45 | |

Throughput (number of finished consultant episodes) includes non-waiting list patients.

% contributed by hospital trusts forming the upper quarter of numbers of patients with prolonged waits to the total numbers waiting >6 months in England.

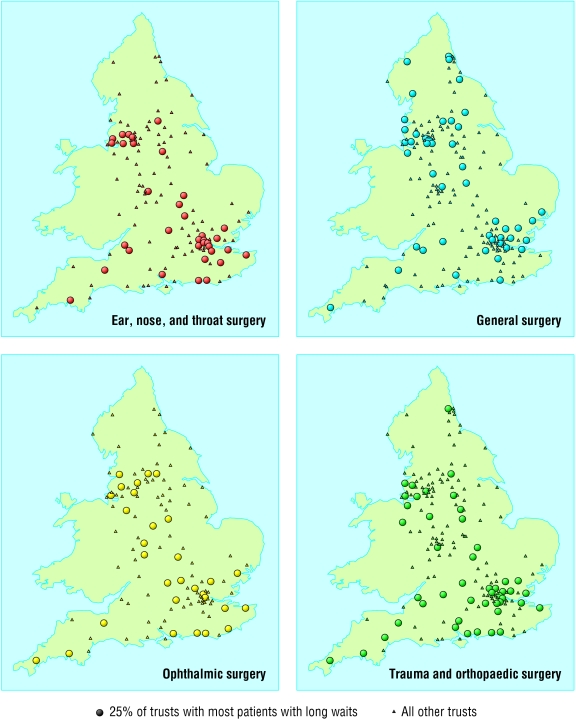

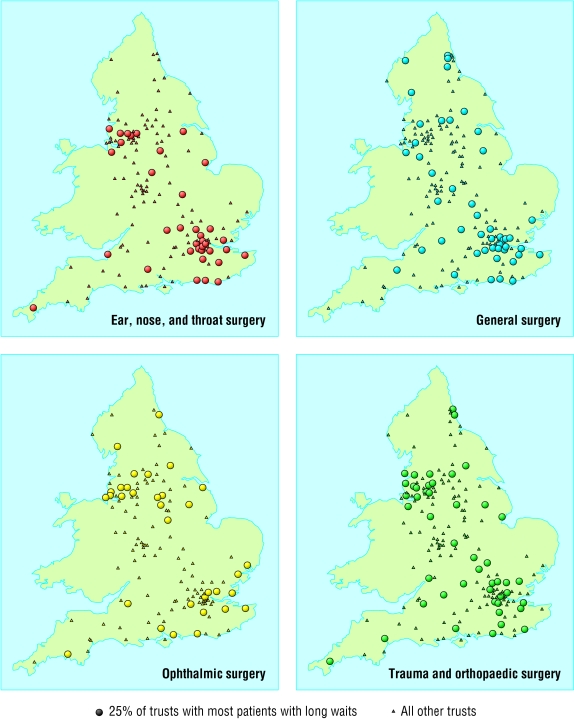

Trusts with the most (top 25% of the distribution) patients with prolonged waits in 1999 were generally clustered along the south coast, in London, and in the north west (fig 2 and fig 3).

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of trusts with the most (top 25% of the distribution) patients with prolonged waits in relation to all other trusts: England, 1999—inpatient elective surgery

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of trusts with the most (top 25% of the distribution) patients with prolonged waits in relation to all other trusts: England, 1999—day case surgery

Correlation matrices

Numbers of patients waiting longer than six months were moderately correlated with numbers of finished consultant episodes, daily available beds, anaesthetists per 100 beds, operating theatres, and dedicated day case theatres (see table A on bmj.com). Correlations between prolonged waiting and both independent activity and need were weak.

Characteristics of trusts forming the upper fourth

Trusts with the most patients with prolonged waits had more available beds and, for some specialties, a higher bed occupancy rate (table 2). In multivariable models, the odds of a trust being in the upper fourth of the distribution of patients with prolonged waits increased by 49-110% per third of total bed availability across specialties, and by 42-69% per third of bed occupancy for ear, nose, and throat surgery and trauma or orthopaedic surgery. Trusts in the upper fourth also tended to have a higher number of anaesthetists. Trusts with the most patients with prolonged waits for general surgery had higher private sector activity in their health authority and more surgeons for trauma and orthopaedic surgery than other trusts. In general, markers of greater need for health care, such as Jarman score, were inversely associated with prolonged waiting. Some evidence showed that trusts with the most patients whose waits for inpatient general surgery were prolonged were more likely to be teaching hospitals, but the pattern was not consistent across specialties and the directions of the effect estimates were reversed for ear, nose, and throat surgery and ophthalmic surgery in multivariable models. Three star rating was inversely associated with prolonged waiting.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis showing associations between hospital trusts forming the upper quarter of numbers of patients with prolonged waits for inpatient elective surgery, with hospital capacity, private provision, and markers of population ill health, by specialty. Values are odds ratios (95% confidence intervals, P values)

| General surgery

|

Ear, nose, and throat surgery

|

Ophthalmic surgery

|

Trauma or orthopaedic surgery

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS capacity

|

||||

| No of operating theatres: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.64 (0.93 to 2.86, P=0.085) | 1.39 (0.80 to 2.42, P=0.24) | 1.03 (0.57 to 1.86, P=0.92) | 1.25 (0.73 to 2.15, P=0.41) |

| Adjusted model | 0.99 (0.47 to 2.07, P=0.97) | 1.04 (0.49 to 2.21, P=0.92) | 0.62 (0.25 to 1.56, P=0.31) | 0.86 (0.38 to 1.92, P=0.71) |

| No of dedicated day case theatres: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.28 (0.85 to 1.91, P=0.23) | 1.22 (0.77 to 1.93, P=0.39) | 1.04 (0.58 to 1.85, P=0.90) | 1.07 (0.70 to 1.64, P=0.74) |

| Adjusted model | 1.04 (0.66 to 1.64, P=0.88) | 1.10 (0.64 to 1.88, P=0.74) | 1.01 (0.51 to 1.99, P=0.98) | 1.08 (0.64 to 1.83, P=0.78) |

| Average daily No of available beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.56 (0.93 to 2.60, P=0.092) | 1.30 (0.76 to 2.24, P=0.34) | 1.24 (0.69 to 2.22, P=0.47) | 1.12 (0.66 to 1.89, P=0.68) |

| Adjusted model | 1.49 (0.83 to 2.64, P=0.18) | 1.57 (0.85 to 2.90, P=0.15) | 2.10 (1.00 to 4.39, P=0.05) | 2.04 (1.01 to 4.11, P=0.046) |

| Bed occupancy rate (%): | ||||

| Simple model | 1.11 (0.72 to 1.72, P=0.64) | 1.65 (1.00 to 2.73, P=0.05) | 0.96 (0.56 to 1.64, P=0.88) | 1.39 (0.86 to 2.24, P=0.18) |

| Adjusted model | 1.15 (0.72 to 1.83, P=0.57) | 1.69 (0.98 to 2.92, P=0.058) | 0.96 (0.54 to 1.70, P=0.88) | 1.42 (0.84 to 2.41, P=0.19) |

| No of anaesthetists per 100 beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.75 (1.11 to 2.74, P=0.015) | 1.47 (0.90 to 2.41, P=0.13) | 1.47 (0.85 to 2.52, P=0.17) | 1.79 (1.10 to 2.90, P=0.019) |

| Adjusted model | 1.76 (1.05 to 2.95, P=0.033) | 1.39 (0.80 to 2.42, P=0.25) | 1.45 (0.80 to 2.63, P=0.22) | 1.44 (0.83 to 2.49, P=0.20) |

| Specialty specific No of surgeons per 100 beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.15 (0.74 to 1.78, P=0.54) | 1.07 (0.65 to 1.75, P=0.78) | 1.53 (0.85 to 2.75, P=0.16) | 1.84 (1.12 to 3.03, P=0.016) |

| Adjusted model | 1.02 (0.60 to 1.72, P=0.95) | 0.99 (0.57 to 1.73, P=0.97) | 1.89 (0.92 to 3.88, P=0.081) | 1.93 (1.01 to 3.70, P=0.047) |

| Independent sector activity | ||||

| No of private hospitals and clinics: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.32 (0.77 to 2.27, P=0.31) | 1.31 (0.75 to 2.28, P=0.35) | 1.11 (0.55 to 2.23, P=0.78) | 1.32 (0.71 to 2.48, P=0.38) |

| Adjusted model | 1.13 (0.64 to 2.00, P=0.67) | 1.16 (0.64 to 2.11, P=0.62) | 1.07 (0.51 to 2.24, P=0.85) | 1.09 (0.56 to 2.14, P=0.79) |

| No of beds in private hospitals and clinics: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.74 (0.99 to 3.05, P=0.054) | 1.43 (0.79 to 2.57, P=0.23) | 1.08 (0.54 to 2.16, P=0.82) | 1.56 (0.86 to 2.83, P=0.14) |

| Adjusted model | 2.00 (1.00 to 4.01, P=0.051) | 1.06 (0.51 to 2.19, P=0.87) | 1.08 (0.47 to 2.49, P=0.86) | 1.31 (0.62 to 2.79), P=0.48) |

| Markers of healthcare need | ||||

| Proportion of population aged >65: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.13 (0.74 to 1.73, P=0.57) | 0.80 (0.50 to 1.30, P=0.37) | 0.74 (0.43 to 1.25, P=0.26) | 0.92 (0.59 to 1.44, P=0.72) |

| Adjusted model | 1.07 (0.63 to 1.82, P=0.80) | 0.78 (0.43 to 1.40, P=0.41) | 0.59 (0.29 to 1.18, P=0.13) | 0.93 (0.53 to 1.64, P=0.80) |

| Jarman score: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.18 (0.76 to 1.85, P=0.45) | 0.87 (0.52 to 1.46, P=0.61) | 0.92 (0.52 to 1.62, P=0.77) | 0.87 (0.54 to 1.40, P=0.55) |

| Adjusted model | 1.07 (0.60 to 1.92, P=0.81) | 0.83 (0.43 to 1.58, P=0.57) | 0.57 (0.27 to 1.24, P=0.16) | 0.92 (0.48 to 1.76, P=0.79) |

| Standardised mortality ratio: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.93 (0.58 to 1.47, P=0.74) | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.23, P=0.23) | 0.95 (0.54 to 1.70, P=0.87) | 0.69 (0.43 to 1.11, P=0.13) |

| Adjusted model | 0.79 (0.36 to 1.76, P=0.57) | 0.93 (0.38 to 2.24, P=0.87) | 0.68 (0.25 to 1.86, P=0.45) | 1.06 (0.46 to 2.46, P=0.89) |

| Rate of limiting long term illness (%): | ||||

| Simple model | 1.05 (0.64 to 1.71, P=0.86) | 0.57 (0.32 to 1.01, P=0.055) | 0.87 (0.46 to 1.65, P=0.67) | 0.56 (0.34 to 0.93, P=0.024) |

| Adjusted model | 1.30 (0.56 to 3.01, P=0.54) | 0.68 (0.27 to 1.73, P=0.41) | 1.66 (0.56 to 4.91, P=0.36) | 0.61 (0.26 to 1.43, P=0.25) |

| Other trust characteristics | ||||

| Acute teaching trust status*: | ||||

| Simple model | 3.84 (1.51 to 9.76, P=0.005) | 1.63 (0.59 to 4.47, P=0.35) | 1.42 (0.45 to 4.47, P=0.55) | 2.35 (0.77 to 7.13, P=0.13) |

| Adjusted model | 2.52 (0.67 to 9.51, P=0.17) | 0.72 (0.16 to 3.19, P=0.67) | 0.47 (0.09 to 2.59, P=0.39) | 1.43 (0.33 to 6.19, P=0.63) |

| Three star status†: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.75 (0.29 to 1.98, P=0.56) | 0.45 (0.14 to 1.46, P=0.19) | 0.64 (0.19 to 2.16, P=0.48) | 0.49 (0.18 to 1.38, P=0.18) |

| Adjusted model | 0.78 (0.28 to 2.20, P=0.64) | 0.56 (0.16 to 1.93, P=0.36) | 0.75 (0.20 to 2.79, P=0.67) | 0.51 (0.16 to 1.57, P=0.24) |

Effect size is odds ratio (upper quarter of trusts v lower three quarters) per unit increase in third of each explanatory variable.

Simple model controls for population denominator and total number of finished consultant episodes only. Adjusted model also controls for number of available beds, number of anaesthetists, number of specialty specific surgeons, number of private beds, proportion of people aged >65 years, Jarman score, standardised mortality ratio, rate of limiting long term illness.

Odds ratios >1 indicate a positive association between being an acute teaching hospital and prolonged waiting, and an odds ratio <1 indicates an inverse association.

Odds ratios >1 indicate a positive association between being rated three stars and prolonged waiting, and an odds ratio <1 indicates an inverse association.

Prolonged waiting for day case ear, nose, and throat surgery was associated with higher rates of bed occupancy and numbers of anaesthetists (table 3). Trusts with the most patients with prolonged waits for day case ophthalmic surgery had more private premises, a higher standardised mortality ratio, and a higher proportion of the population over 65 at health authority level but an inverse association with the rate of limiting long term illness. Trusts with the most patients whose waiting for day case surgery was prolonged were less likely to be teaching hospitals (table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis showing associations between hospital trusts in the upper fourth of numbers of patients with prolonged waits for day case elective surgery, with hospital capacity, private provision, and markers of ill health of the population, by specialty. Values are odds ratios (95% confidence intervals, P values)

| General surgery

|

Ear, nose, and throat surgery

|

Ophthalmic surgery

|

Trauma or orthopaedic surgery

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS capacity | ||||

| No of operating theatres: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.87 (0.50 to 1.50, P=0.61) | 1.22 (0.69 to 2.14, P=0.49) | 1.53 (0.86 to 2.71, P=0.15) | 1.17 (0.71 to 1.93, P=0.53) |

| Adjusted model | 0.87 (0.42 to 1.78, P=0.70) | 1.14 (0.52 to 2.49, P=0.75) | 0.83 (0.33 to 2.07, P=0.69) | 1.19 (0.60 to 2.36, P=0.63) |

| No of dedicated day case theatres: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.91 (0.61 to 1.35, P=0.63) | 1.32 (0.85 to 2.07, P=0.22) | 1.19 (0.68 to 2.08, P=0.55) | 0.72 (0.48 to 1.08, P=0.12) |

| Adjusted model | 0.93 (0.58 to 1.47, P=0.75) | 1.34 (0.79 to 2.27, P=0.28) | 1.21 (0.58 to 2.53, P=0.60) | 0.61 (0.38 to 0.98, P=0.042) |

| Average daily No of available beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.69 (0.42 to 1.16, P=0.16) | 0.96 (0.57 to 1.63, P=0.88) | 1.91 (1.05 to 3.48, P=0.034) | 0.97 (0.61 to 1.55, P=0.90) |

| Adjusted model | 0.91 (0.51 to 1.64, P=0.76) | 1.27 (0.70 to 2.33, P=0.43) | 2.46 (1.12 to 5.40, P=0.025) | 1.23 (0.67 to 2.26, P=0.51) |

| Bed occupancy rate (%): | ||||

| Simple model | 1.23 (0.80 to 1.88, P=0.34) | 2.01 (1.22 to 3.30, P=0.006) | 0.94 (0.57 to 1.57, P=0.82) | 1.05 (0.69 to 1.59, P=0.83) |

| Adjusted model | 1.23 (0.78 to 1.94, P=0.38) | 2.53 (1.45 to 4.41, P=0.001) | 0.88 (0.47 to 1.67, P=0.70) | 1.07 (0.69 to 1.65, P=0.76) |

| No of anaesthetists per 100 beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.17 (0.77 to 1.79, P=0.46) | 1.61 (1.00 to 2.60, P=0.048) | 0.83 (0.48 to 1.42, P=0.50) | 1.32 (0.86 to 2.02, P=0.20) |

| Adjusted model | 0.85 (0.50 to 1.43, P=0.54) | 1.70 (1.00 to 2.90, P=0.052) | 0.83 (0.44 to 1.54, P=0.55) | 1.33 (0.81 to 2.18, P=0.25) |

| Specialty specific No of surgeons per 100 beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.57 (1.01 to 2.42, P=0.043) | 1.48 (0.91 to 2.41, P=0.11) | 0.79 (0.45 to 1.39, P=0.41) | 1.15 (0.76 to 1.75, P=0.51) |

| Adjusted model | 1.48 (0.89 to 2.45, P=0.13) | 1.38 (0.81 to 2.35, P=0.23) | 0.87 (0.42 to 1.80, P=0.71) | 1.05 (0.61 to 1.81, P=0.85) |

| Independent sector activity | ||||

| No of private hospitals and clinics: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.97 (0.57 to 1.63, P=0.90) | 0.81 (0.46 to 1.41, P=0.45) | 1.21 (0.60 to 2.42, P=0.59) | 1.17 (0.71 to 1.92, P=0.54) |

| Adjusted model | 0.92 (0.52 to 1.63, P=0.78) | 0.68 (0.37 to 1.22, P=0.20) | 2.77 (1.08 to 7.10, P=0.033) | 1.07 (0.62 to 1.84, P=0.81) |

| No of beds in private hospitals and clinics: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.57 (0.91 to 2.70, P=0.10) | 0.87 (0.49 to 1.53, P=0.63) | 0.81 (0.41 to 1.61, P=0.55) | 1.28 (0.75 to 2.20, P=0.37) |

| Adjusted model | 1.60 (0.80 to 3.17, P=0.18) | 0.88 (0.44 to 1.74, P=0.70) | 0.89 (0.33 to 2.37, P=0.81) | 1.33 (0.67 to 2.62, P=0.42) |

| Markers of healthcare need | ||||

| Proportion of population aged >65: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.02 (0.68 to 1.53, P=0.93) | 0.79 (0.50 to 1.25, P=0.31) | 1.49 (0.88 to 2.51, P=0.14) | 1.13 (0.75 to 1.70, P=0.57) |

| Adjusted model | 1.12 (0.67 to 1.88, P=0.67) | 0.62 (0.33 to 1.18, P=0.14) | 3.23 (1.43 to 7.33, P=0.005) | 1.03 (0.62 to 1.70, P=0.91) |

| Jarman score: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.62 (0.39 to 0.96, P=0.032) | 0.71 (0.44 to 1.13, P=0.15) | 0.81 (0.46 to 1.45, P=0.48) | 0.76 (0.49 to 1.16, P=0.20) |

| Adjusted model | 0.88 (0.51 to 1.52, P=0.65) | 0.69 (0.38 to 1.26, P=0.23) | 0.50 (0.22 to 1.15, P=0.10) | 0.70 (0.39 to 1.23, P=0.21) |

| Standardised mortality ratio: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.57 (0.36 to 0.90, P=0.017) | 0.69 (0.42 to 1.16, P=0.16) | 1.38 (0.78 to 2.45, P=0.26) | 0.78 (0.50 to 1.22, P=0.28) |

| Adjusted model | 1.10 (0.52 to 2.32, P=0.81) | 0.61 (0.26 to 1.43, P=0.26) | 8.67 (2.20 to 34.19, P=0.002) | 0.87 (0.42 to 1.79, P=0.71) |

| Rate of limiting long term illness (%): | ||||

| Simple model | 0.42 (0.25 to 0.71, P=0.001) | 0.66 (0.39 to 1.12, P=0.13) | 1.07 (0.59 to 1.94, P=0.82) | 0.84 (0.54 to 1.32, P=0.45) |

| Adjusted model | 0.43 (0.19 to 0.96, P=0.040) | 1.38 (0.58 to 3.26, P=0.47) | 0.22 (0.07 to 0.75, P=0.016) | 1.12 (0.54 to 2.32, P=0.77) |

| Other trust characteristics | ||||

| Acute teaching trust status*: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.57 (0.19 to 1.67, P=0.30) | 0.77 (0.24 to 2.51, P=0.67) | 0.93 (0.29 to 3.00, P=0.91) | 1.12 (0.40 to 3.13, P=0.83) |

| Adjusted model | 0.67 (0.16 to 2.72, P=0.57) | 0.38 (0.08 to 1.96, P=0.25) | 0.22 (0.03 to 1.40, P=0.11) | 0.98 (0.25 to 3.81, P=0.98) |

| Three star status†: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.01 (0.41 to 2.51, P=0.98) | 0.41 (0.11 to 1.49, P=0.18) | 1.28 (0.42 to 3.92, P=0.66) | 0.87 (0.34 to 2.20, P=0.77) |

| Adjusted model | 1.26 (0.46 to 3.40, P=0.65) | 0.42 (0.11 to 1.60, P=0.20) | 0.82 (0.23 to 2.89, P=0.75) | 0.90 (0.34 to 2.40, P=0.84) |

Effect size is odds ratio (upper quarter of trusts v lower three quarters) per unit increase in third of each explanatory variable.

Simple model controls for population denominator and total number of finished consultant episodes only. Adjusted model also controls for number of available beds, number of anaesthetists, number of specialty specific surgeons, number of private beds, proportion of people aged >65 years, Jarman score, standardised mortality ratio, rate of limiting long term illness.

Odds ratios >1 indicate a positive association between being an acute teaching hospital and prolonged waiting, and an odds ratio <1 indicates an inverse association.

Odds ratios >1 indicate a positive association between being rated three stars and prolonged waiting, and an odds ratio <1 indicates an inverse association.

The characteristics of the highest tenth of trusts for numbers of patients with prolonged waits were similar to those in the top fourth, although associations of bed occupancy rates with general and ear, nose, and throat surgery (both elective and day case) were stronger than for those in the top fourth (data not shown).

Associations were generally similar when we examined the entire distribution of prolonged waiting, using negative binomial regression (tables 4 and 5). When the formal likelihood ratio tests for interaction were performed there was little evidence that associations varied according to the throughput of the hospital (defined as above or below the median number of specialty specific finished consultant episodes).

Table 4.

Negative binomial regression analysis showing the association of rate of prolonged waiting for inpatient elective surgery, with hospital capacity, private provision, and markers of population ill health, by specialty. Values are odds ratios (95% confidence intervals, P values)

| General surgery

|

Ear, nose, and throat surgery

|

Ophthalmic surgery

|

Trauma or orthopaedic surgery

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS capacity | ||||

| No of operating theatres: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.09 (0.93 to 1.28, P=0.31) | 1.19 (0.92 to 1.53, P=0.18) | 1.02 (0.74 to 1.41, P=0.91) | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.27, P=0.22) |

| Adjusted model | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.16, P=0.44) | 0.86 (0.55 to 1.35, P=0.51) | 0.84 (0.43 to 1.65, P=0.61) | 1.02 (0.79 to 1.32, P=0.86) |

| No of dedicated day case theatres: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.24, P=0.38) | 0.90 (0.71 to 1.15, P=0.42) | 0.81 (0.57 to 1.17, P=0.27) | 1.05 (0.91 to 1.20, P=0.50) |

| Adjusted model | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.14, P=0.76) | 1.01 (0.76 to 1.34, P=0.95) | 0.84 (0.54 to 1.31, P=0.44) | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.15, P=0.83) |

| Average daily No of available beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.06 (0.90 to 1.25, P=0.48) | 1.16 (0.91 to 1.48, P=0.24) | 1.05 (0.71 to 1.56, P=0.80) | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.26, P=0.28) |

| Adjusted model | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.13, P=0.42) | 0.92 (0.64 to 1.32, P=0.64) | 1.66 (0.93 to 2.96, P=0.086) | 1.13 (0.91 to 1.40, P=0.28) |

| Bed occupancy rate (%): | ||||

| Simple model | 1.08 (0.93 to 1.27, P=0.31) | 1.42 (1.10 to 1.83, P=0.007) | 0.85 (0.60 to 1.19, P=0.34) | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.17, P=0.84) |

| Adjusted model | 1.08 (0.92 to 1.26, P=0.34) | 1.14 (0.88 to 1.49, P=0.32) | 0.84 (0.58 to 1.21, P=0.35) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17, P=0.92) |

| No of anaesthetists per 100 beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.45 (1.24 to 1.70, P<0.001) | 1.50 (1.16 to 1.94, P=0.002) | 1.11 (0.79 to 1.57, P=0.55) | 1.16 (1.00 to 1.34, P=0.049) |

| Adjusted model | 1.40 (1.13 to 1.72, P=0.002) | 1.10 (0.77 to 1.58, P=0.60) | 1.50 (0.86 to 2.61, P=0.15) | 1.19 (0.98 to 1.43, P=0.075) |

| Specialty specific No of surgeons per 100 beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.10 (0.94 to 1.29, P=0.25) | 1.15 (0.86 to 1.52, P=0.35) | 1.31 (0.88 to 1.93, P=0.18) | 1.10 (0.95 to 1.27, P=0.19) |

| Adjusted model | 1.10 (0.93 to 1.30, P=0.29) | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.41, P=0.60) | 1.73 (1.13 to 2.67, P=0.011) | 1.16 (0.98 to 1.37, P=0.091) |

| Independent sector activity | ||||

| No of private hospitals and clinics: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.00 (0.82 to 1.22, P=0.99) | 0.82 (0.62 to 1.09, P=0.18) | 0.89 (0.53 to 1.49, P=0.66) | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.21, P=0.94) |

| Adjusted model | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.08, P=0.19) | 0.89 (0.63 to 1.25, P=0.49) | 0.70 (0.40 to 1.21, P=0.20) | 1.05 (0.85 to 1.29, P=0.67) |

| No of beds in private hospitals and clinics: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.16 (0.96 to 1.40, P=0.13) | 0.85 (0.64 to 1.12, P=0.24) | 1.29 (0.78 to 2.14, P=0.33) | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30, P=0.40) |

| Adjusted model | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.28, P=0.72) | 0.77 (0.55 to 1.07, P=0.13) | 1.04 (0.57 to 1.90, P=0.90) | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.20, P=0.88) |

| Markers of healthcare need | ||||

| Proportion of population aged >65: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.90 (0.77 to 1.05, P=0.17) | 0.75 (0.59 to 0.94, P=0.014) | 0.97 (0.68 to 1.38, P=0.86) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.11, P=0.61) |

| Adjusted model | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.19, P=0.93) | 0.77 (0.57 to 1.04, P=0.086) | 1.10 (0.65 to 1.87, P=0.72) | 0.94 (0.78 to 1.12, P=0.47) |

| Jarman score: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.15, P=0.82) | 0.72 (0.57 to 0.93, P=0.010) | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.02, P=0.064) | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.07, P=0.28) |

| Adjusted model | 1.12 (0.92 to 1.36, P=0.27) | 0.84 (0.61 to 1.15, P=0.27) | 0.51 (0.30 to 0.88, P=0.015) | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.16, P=0.67) |

| Standardised mortality ratio: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.89 (0.75 to 1.06, P=0.18) | 0.72 (0.56 to 0.92, P=0.009) | 0.75 (0.49 to 1.14, P=0.17) | 0.86 (0.74 to 1.00, P=0.046) |

| Adjusted model | 0.90 (0.69 to 1.17, P=0.44) | 0.95 (0.63 to 1.42, P=0.79) | 0.77 (0.40 to 1.46, P=0.42) | 0.94 (0.75 to 1.18, P=0.58) |

| Rate of limiting long term illness (%): | ||||

| Simple model | 0.82 (0.69 to 0.97, P=0.024) | 0.59 (0.46 to 0.77, P<0.001) | 0.75 (0.50 to 1.13, P=0.17) | 0.80 (0.68 to 0.93, P=0.005) |

| Adjusted model | 0.86 (0.66 to 1.13, P=0.28) | 0.74 (0.48 to 1.13, P=0.16) | 1.27 (0.67 to 2.40, P=0.46) | 0.81 (0.64 to 1.03, P=0.085) |

| Other trust characteristics | ||||

| Acute teaching trust status*: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.39 (0.96 to 2.02, P=0.080) | 2.39 (1.36 to 4.21, P=0.003) | 1.13 (0.49 to 2.60, P=0.77) | 1.21 (0.85 to 1.73, P=0.29) |

| Adjusted model | 1.01 (0.62 to1.65, P=0.95) | 1.80 (0.88 to 3.68, P=0.11) | 1.75 (0.59 to 5.22, P=0.31) | 1.08 (0.69 to 1.69, P=0.75) |

| Three star status†: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.86 (0.61 to 1.22, P=0.40) | 0.76 (0.44 to 1.33, P=0.34) | 0.79 (0.38 to 1.64, P=0.53) | 0.89 (0.64 to 1.23, P=0.49) |

| Adjusted model | 0.87 (0.62 to1.23, P=0.42) | 0.88 (0.50 to 1.55, P=0.65) | 0.83 (0.36 to 1.92, P=0.66) | 0.90 (0.65 to 1.25, P=0.53) |

Effect size is rate ratio for each unit increase in third of each explanatory variable.

Simple model controls for population denominator and total number of finished consultant episodes only. Adjusted model also controls for number of available beds, number of anaesthetists, number of specialty specific surgeons, number of private beds, proportion of people aged >65 years, Jarman score, standardised mortality ratio, rate of limiting long term illness.

Rate ratios >1 indicate a positive association between being an acute teaching hospital and prolonged waiting, and rate ratios <1 indicate an inverse association.

Rate ratios >1 indicate a positive association between being rated three stars and prolonged waiting, and rate ratios <1 indicate an inverse association.

Table 5.

Negative binomial regression analysis showing the association of rate of prolonged waiting for day case elective surgery, with hospital capacity, private provision, and markers of ill health of the population, by specialty. Values are odds ratios (95% confidence intervals, P values)

| General surgery

|

Ear, nose, and throat surgery

|

Ophthalmic surgery

|

Trauma or orthopaedic surgery

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS capacity | ||||

| No of operating theatres: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.17, P=0.69) | 0.59 (0.42 to 0.82, P=0.002) | 0.95 (0.73 to 1.22, P=0.67) | 0.91 (0.74 to 1.11, P=0.35) |

| Adjusted model | 0.99 (0.73 to 1.36, P=0.97) | 1.09 (0.58 to 2.02, P=0.79) | 0.90 (0.58 to 1.40, P=0.65) | 0.97 (0.69 to 1.36, P=0.85) |

| No of dedicated day case theatres: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.18, P=0.83) | 1.46 (1.04 to 2.05, P=0.029) | 0.93 (0.72 to 1.20, P=0.59) | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.98, P=0.031) |

| Adjusted model | 0.93 (0.76,1 to 14, P=0.48) | 1.52 (1.09 to 2.13, P=0.014) | 0.96 (0.70 to 1.31, P=0.80) | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01, P=0.056) |

| Average daily No of available beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.03, P=0.10) | 0.55 (0.40 to 0.75, P<0.001) | 1.02 (0.78 to 1.32, P=0.89) | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.06, P=0.17) |

| Adjusted model | 0.83 (0.63 to 1.10, P=0.19) | 0.59 (0.36 to 0.96, P=0.035) | 1.35 (0.91 to 1.99, P=0.13) | 1.02 (0.77 to 1.35, P=0.90) |

| Bed occupancy rate (%): | ||||

| Simple model | 1.06 (0.87 to 1.28, P=0.57) | 2.51 (1.65 to 3.80, P<0.001) | 1.12 (0.88 to 1.43, P=0.36) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.26, P=0.72) |

| Adjusted model | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.22, P=0.96) | 1.72 (1.23 to 2.43, P=0.002) | 1.11 (0.84 to 1.45, P=0.46) | 1.01 (0.83 to 1.23, P=0.92) |

| No of anaesthetists per 100 beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.19 (0.97 to 1.46, P=0.10) | 2.44 (1.73 to 3.45, P<0.001) | 0.96 (0.75 to 1.23, P=0.75) | 1.01 (0.83 to 1.24, P=0.89) |

| Adjusted model | 1.15 (0.87 to 1.52, P=0.31) | 1.67 (1.07 to 2.63, P=0.025) | 1.10 (0.77 to 1.55, P=0.61) | 1.00 (0.75 to 1.34, P=0.99) |

| Specialty specific No of surgeons per 100 beds: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.05 (0.87 to 1.28, P=0.60) | 1.69 (1.18 to 2.42, P=0.004) | 1.08 (0.83 to 1.39, P=0.57) | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.26, P=0.77) |

| Adjusted model | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.27, P=0.86) | 1.10 (0.77 to 1.57; P=0.60) | 1.29 (0.96 to 1.73, P=0.09) | 1.01 (0.79 to 1.28, P=0.94) |

| Independent sector activity | ||||

| No of private hospitals and clinics: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.97 (0.75 to 1.26, P=0.83) | 0.67 (0.41 to 1.09, P=0.11) | 0.92 (0.62 to 1.34, P=0.65) | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.19, P=0.59) |

| Adjusted model | 0.98 (0.74 to 1.29, P=0.87) | 0.61 (0.37 to 0.99, P=0.047) | 0.98 (0.65 to 1.47, P=0.92) | 0.93 (0.71 to 1.23, P=0.61) |

| No of beds in private hospitals and clinics: | ||||

| Simple model | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.35, P=0.73) | 1.06 (0.72 to 1.57, P=0.76) | 0.97 (0.65 to 1.44, P=0.88) | 1.07 (0.83 to 1.39, P=0.59) |

| Adjusted model | 0.98 (0.73 to 1.31, P=0.88) | 0.57 (0.37 to 0.87, P=0.010) | 1.17 (0.76 to 1.78, P=0.48) | 0.95 (0.71 to 1.28, P=0.75) |

| Markers of healthcare need | ||||

| Proportion of population aged >65: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.18, P=0.81) | 0.66 (0.46 to 0.95, P=0.025) | 1.17 (0.92 to 1.49, P=0.20) | 0.95 (0.78 to 1.16, P=0.62) |

| Adjusted model | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.41, P=0.32) | 0.66 (0.44 to 1.00, P=0.047) | 1.30 (0.94 to 1.81, P=0.11) | 1.10 (0.83 to 1.46, P=0.50) |

| Jarman score: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.10, P=0.30) | 0.50 (0.36 to 0.68, P<0.001) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.96, P=0.021) | 0.81 (0.67 to 0.99, P=0.036) |

| Adjusted model | 1.23 (0.96 to 1.57, P=0.11) | 1.15 (0.75 to 1.77, P=0.53) | 0.59 (0.40 to 0.85, P=0.005) | 0.87 (0.67 to 1.12, P=0.28) |

| Standardised mortality ratio: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.79 (0.63 to 0.99, P=0.037) | 0.41 (0.30 to 0.58, P<0.001) | 1.02 (0.77 to 1.35, P=0.91) | 0.85 (0.67 to 1.07, P=0.17) |

| Adjusted model | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.31, P=0.73) | 0.50 (0.28 to 0.87, P=0.014) | 1.53 (1.00 to 2.32, P=0.048) | 1.00 (0.70 to 1.42, P=1.00) |

| Rate of limiting long term illness (%): | ||||

| Simple model | 0.69 (0.55 to 0.86, P=0.001) | 0.41 (0.30 to 0.57, P<0.001) | 0.88 (0.64 to 1.20, P=0.41) | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.96, P=0.019) |

| Adjusted model | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.00, P=0.053) | 0.84 (0.47 to 1.51, P=0.56) | 0.73 (0.47 to 1.14, P=0.16) | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.20, P=0.34) |

| Other trust characteristics | ||||

| Acute teaching trust status*: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.67 (0.42 to 1.06, P=0.088) | 1.00 (0.43 to 2.29, P=0.99) | 0.53 (0.30 to 0.94, P=0.030) | 0.75 (0.46 to 1.23, P=0.25) |

| Adjusted model | 0.60 (0.33 to 1.10, P=0.10) | 0.96 (0.35 to 2.64, P=0.93) | 0.44 (0.20 to 0.96, P=0.040) | 0.89 (0.45 to 1.73, P=0.72) |

| Three star status†: | ||||

| Simple model | 0.76 (0.50 to 1.17, P=0.21) | 0.20 (0.10 to 0.43, P<0.001) | 1.23 (0.71 to 2.12, P=0.46) | 0.85 (0.55 to 1.33, P=0.48) |

| Adjusted model | 0.88 (0.56 to 1.38, P=0.58) | 0.50 (0.24 to 1.07, P=0.073) | 1.07 (0.62 to 1.87, P=0.80) | 0.90 (0.57 to 1.43, P=0.67) |

Effect size is rate ratio for each unit increase in third of each explanatory variable.

Simple model controls for population denominator and total number of finished consultant episodes only. Adjusted model also controls for number of available beds, number of anaesthetists, number of specialty specific surgeons, number of private beds, proportion of people aged >65 years, Jarman score, standardised mortality ratio, rate of limiting long term illness.

Rate ratios >1 indicate a positive association between being an acute teaching hospital and prolonged waiting, and rate ratios <1 indicate an inverse association.

Rate ratios >1 indicate a positive association between being rated three stars and prolonged waiting, and rate ratios <1 indicate an inverse association.

In trusts providing all four specialties, correlations between specialties in rates of prolonged waiting for inpatient elective surgery ranged from −0.01 (ear, nose, and throat surgery, ophthalmic surgery) to 0.52 (general, and trauma and orthopaedic surgery) and for day case surgery they ranged from 0.05 (ear, nose, and throat surgery, ophthalmic surgery) to 0.36 (general and trauma and orthopaedic surgery). All but one of the correlations for inpatient admissions were ⩾0.20, and for day case admissions all but one of the correlations were >0.15 (table 6).

We repeated the analyses with cut offs of nine months or longer and 12 months, and the overall pattern of results was similar. We also repeated the analysis with numbers of operating theatres and dedicated day case theatres rescaled as rates per 100 beds; available beds as a rate per finished consultant episodes; and numbers of private hospitals and beds as rates per 1000 health authority population. The overall pattern of results did not alter.

Discussion

Despite widespread political and media attention little empirical evidence exists on the distribution of waiting and prolonged waiting in England. In most instances substantial numbers of patients waiting longer than six months in the main surgical specialties are restricted to a relatively small proportion of hospitals.

We found little and inconsistent evidence that capacity—as measured by numbers of operating theatres, dedicated day case theatres, available beds, or bed occupancy rate—is associated with prolonged waiting. In line with previous research we found that trusts with more consultant surgeons and anaesthetists had more patients whose waits were prolonged.15 The supply of doctors can induce demand,16,17 but further work is required to determine if this is the explanation for the observed association. Numbers of anaesthetists, for example, could be a marker for some other relevant characteristic such as the complexity of work undertaken.

We found little evidence that activity in the independent sector influenced prolonged waiting, apart from a positive association of private premises with prolonged waiting for day case ophthalmic surgery (table 4), in line with data on waiting for cataract surgery in Canada.1

In general, trusts in health authorities with higher potential need had fewer patients with prolonged waits. Possible explanations include uncontrolled confounding factors, such as referral rates from general practitioners. Secondly, observed inverse associations of prolonged waiting with markers of increased need may reflect inequalities in access to elective surgery in deprived populations (for reasons other than general practitioners' referral rates).18 Thirdly, the findings could indicate NHS success in targeting resources towards where they are needed most. In support of this possibility, we found some evidence of a positive relation between need and capacity (such as positive correlations of Jarman score, standardised mortality ratio, and rate of long term limiting illness with numbers of available beds and operating theatres; table 2), although this evidence was inconsistent (for example, correlations with numbers of anaesthetists and general surgeons were negative). Finally, our data do not rule out the possibility that in affluent areas with more patients with prolonged waits, patients who are waiting unacceptably long periods are socioeconomically deprived, a finding that would be in line with that of a study on waiting times for bypass surgery.19

Limitations

We used many different sources of data, most of which came directly from the Department of Health. Although the completeness and accuracy of some of these data may be imperfect, they were the only national source for our analysis, and such data have previously been used to model demand for health care.20 The waiting list data forming the basis of this analysis are used to monitor the performance of NHS trusts.21 They are published as the established statistics on waiting lists, and trusts are required to validate their waiting lists on a regular basis.22,23 As some of the explanatory measures are relatively crude proxies of what we were seeking to measure (for example, finished consultant episodes as a proxy for the population served) these (generally random) errors may lead us to underestimate (or miss) associations. For a source of bias to influence our findings systematically, any misclassification would have to be related to prolonged waiting, which seems unlikely.

Statistics on hospital waiting lists obtained from KH07 quarterly returns provide a cross sectional record of the number of people still waiting for elective surgery in categories of three months' waiting time, censored at the end of each quarter (in this study, 31 December 1999), rather than the full length of time to admission of all those listed. We do not know what happened to each patient censored, and a life table analysis implies that KHO7 returns may overestimate short waiting times.24 But this limitation should not be a problem in our paper as prolonged waiting times were the focus of interest. Hospital episode statistics provide data on time since enrolment of patients admitted but ignore those who were not admitted, underestimating the waiting time of all those listed.24

We did not include the outpatient waiting list, time spent between waiting lists, or the effect of clinical or self deferral.25 Data on length of time waiting to be put on a list are not routinely available, and it is the inpatient waiting list that is the current focus of political attention.

Differences exist between districts over what constitutes a finished consultant episode, the denominator in our analyses.26 Bias would occur if patterns of finished consultant episodes in hospitals with large numbers of patients with prolonged waits reflected different transfer or readmission patterns compared with hospitals with low numbers. Stratification by specialty specific numbers of finished consultant episodes showed no evidence of statistical interaction.

We used specialty specific consultant episodes and the health authority population as our measure of the catchment population of each specialty in each trust. If consultant episodes did not fully capture the size of the catchment population this could explain observed positive associations between some markers of capacity and prolonged waiting. One would then also expect positive associations with other aspects of capacity such as numbers of theatres and dedicated day case theatres, which was not generally observed. The specificity of observed associations provides some evidence that the size of the catchment population was adequately controlled for.

Finally, our analysis is based on waiting list figures for the final quarter of 1999. Although the analysis shows that specific attention to tackle prolonged waiting should probably be focused on the minority of hospitals with the most numbers of spatients with prolonged waits, we have not investigated whether particular hospitals with the most of such patients change over time. This limitation does not affect our finding that measures of capacity and independent sector activity were not generally associated with prolonged waiting.

Implications

This study challenges the widely held assumption that most patients in England are being forced to wait unacceptably long periods of time for elective surgery. This experience may be true for a minority of hospitals, but little evidence supports the notion that the waiting list phenomenon in most hospitals in England arises from an overall mismatch between supply and demand.

Public health specialists classically focus on population based strategies, with the aim of producing favourable shifts in the distribution of risk factors in the entire population.27 Since the distribution of prolonged waiting in hospital trusts is highly positively skewed, this study shows that targeting all trusts is not warranted. Instead a “high risk” strategy is required, focusing measures on the minority of trusts where the waiting list problem is concentrated.

Few studies have examined determinants of prolonged waiting. At an individual level, employment, relative affluence, and higher urgency rating4,28 are associated with less waiting. We have shown that prolonged waiting is not simply related to capacity, implying that many other factors are involved and raising questions about the appropriate policy interventions. Other countries are exploring the use of priority scores to manage waiting lists.29 Clinicians' ratings of appropriateness based on capacity to benefit from surgery have been associated with clinical outcome28 and offer an evidence based, transparent approach to demand management. Such strategies may be a better means than government waiting list targets of reducing inequalities in access to elective surgery.

Waiting lists are a national problem in that they have distorted health policy since the inception of the NHS. They are, however, better seen as a composite of local problems that cannot necessarily be attributed to any obvious disparity between supply and demand. To explain the supply problems surrounding the major waiting list conditions is difficult. For example, rates of total hip replacement are higher in the United Kingdom than the United States, and demand for cataract extraction is well within the current capacity of ophthalmic services.9 The long term underinvestment in British health care is being tackled, but the waiting list problem cannot be expected to be solved by global investment alone.

Supplementary Material

Table.

Table 6 Correlations between specialties in rates of prolonged waiting for inpatient and day case surgery

| General surgery

|

Ear, nose, and throat surgery

|

Ophthalmic surgery

|

Trauma and orthopaedic surgery

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient surgery: | ||||

| General | 1.00 | |||

| Ear, nose, and throat | 0.33 | 1.00 | ||

| Ophthalmic | 0.21 | -0.01 | 1.00 | |

| Trauma and orthopaedic | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 1.00 |

| Day case surgery: | ||||

| General | 1.00 | |||

| Ear, nose, and throat | 0.17 | 1.00 | ||

| Ophthalmic | 0.21 | 0.05 | 1.00 | |

| Trauma and orthopaedic | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 1.00 |

Footnotes

Funding: SF was supported by the Leverhulme Trust during the study period.

Competing interests: None declared.

An extra table appears on bmj.com

References

- 1.DeCoster C, Carriere KC, Peterson S, Walld R, MacWilliam L. Waiting times for surgical procedures. Med Care. 1999;37:JS187–205. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199906001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch X. Catalonia tries to tackle growing waiting lists. BMJ. 1998;316:885. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7135.881i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grouden M, Sheehan S, Colgan MP, Moore D, Shanik G. Results and lessons to be learned from a waiting list initiative. Ir Med J. 1998;91:90–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clover KA, Dobbins TA, Smyth TJ, Sanson-Fisher RW. Factors associated with waiting time for surgery. Med J Aust. 1998;169:464–468. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb127867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derrett S, Paul C, Morris J. Waiting for elective surgery: effects on health-related quality of life. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999;11:47–50. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/11.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niinimaki T. Increasing demands on orthopedic services. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1991;241:42–43. doi: 10.3109/17453679109155106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steensen JP, Jorgensen J. Waiting times for surgery. Ugeskrift for Laeger. 1992;154:647–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankel S. The origins of waiting lists. In: Frankel S, West R, editors. Rationing and rationality in the National Health Service. London: Macmillan; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankel S, Ebrahim S, Davey Smith G. The limits to demand for health care. BMJ. 2000;321:40–45. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7252.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankel S, Eachus J, Pearson N, Greenwood R, Chan P, Peters TJ, et al. Population requirements for primary hip-replacement surgery: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 1999;353:1304–1309. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopper C, Frost NA, Peters TJ, Sparrow JM, Durant JS, Frankel S. Population requirements for cataract surgery. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:661. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health. The NHS Plan. London: Department of Health; 2000. www.nhs.uk/nationalplan/ (accessed 19 Nov 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department of Health. NHS performance ratings and indicators 2002. www.doh.gov.uk/performanceratings/2002/national.html (accessed 3 Dec 2002).

- 14.Long JS. Count outcomes: regression models for counts. In: Long JS, editor. Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. pp. 217–251. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pope C. Cutting queues or cutting corners: waiting lists and the 1990 NHS reforms. BMJ. 1992;305:577–579. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6853.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cromwell J, Mitchell JB. Physician-induced demand for surgery. J Health Econ. 1986;5:293–313. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roland Morris R. Are referrals by general practitioners influenced by the availability of consultants? BMJ. 1989;297:599–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6648.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben-Shlomo Y, Chaturvedi N. Assessing equity in access to health care provision in the UK: does where you live affect your chances of getting a coronary artery bypass graft? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:200–204. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pell JP, Pell AC, Norrie J, Ford I, Cobbe SM. Effect of socioeconomic deprivation on waiting time for cardiac surgery: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:15–18. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carr-Hill RA, Sheldon TA, Smith P, Martin S, Peacock S, Hardman G. Allocating resources to health authorities: development of method for small area analysis. BMJ. 1994;309:1046–1049. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6961.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health. NHS performance indicators: a consultation. London: Department of Health; 2001. www.doh.gov.uk/piconsultation/ (accessed 19 Nov 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Department of Health. NHS waiting times Qtr 3: to 31 Dec 1999. www.doh.gov.uk/waitingtimes/grn19990/g1999_y00_q3.htm (accessed 16 Jul 2002).

- 23.Department of Health. Getting patients treated: the waiting list action team handbook. London: Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong PW. First steps in analysing NHS waiting times: avoiding the ‘stationary and closed’ population fallacy. Stat Med. 2000;19:2037–2051. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20000815)19:15<2037::aid-sim606>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith T. Waiting times: monitoring the total postreferral wait. BMJ. 1994;309:593–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clarke A, McKee M. The consultant episode: an unhelpful measure. BMJ. 1992;305:1307–1308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6865.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 1981;282:1847–1851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemingway H, Crook AM, Feder G, Dawson JR, Timmis A. Waiting for coronary angiography: is there a clinically ordered queue? Lancet. 2000;355:985–986. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fricker J. BMA proposes strategy to reformulate waiting lists. BMJ. 1999;318:78. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7176.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.