Abstract

The surgical treatment of coronary artery anomalies continues to evolve. The most common coronary artery anomalies requiring surgical intervention include coronary artery fistulae, anomalous pulmonary origins of the coronary arteries, and anomalous aortic origins of the coronary arteries. The choice of surgical intervention for each type of coronary anomaly depends on several anatomic, physiologic, and patient-dependent variables. As surgical techniques have progressed, outcomes have continued to improve; however, controversy still exists about many aspects of the proper management of patients who have these coronary artery anomalies.

We reviewed the surgical treatment of 178 patients who underwent surgery for the above-mentioned types of coronary artery anomalies at the Texas Heart Institute from December 1963 through June 2001. On the basis of this experience, we discuss historical aspects of the early treatment of these anomalies and describe their present-day management. (Tex Heart Inst J 2002;29:299–307)

Key words: Aorta/abnormalities/surgery, cardiac surgical procedures, coronary vessel anomalies/classification/surgery, fistula/congenital/surgery, heart defects/congenital/surgery, pulmonary artery/abnormalities

Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries occur in 0.2% to 1.2% of the general population. 1 Most coronary artery anomalies do not cause myocardial ischemia and are often found incidentally during angiographic evaluation for other cardiac diseases. Certain types of anomalies, however, are associated with disruption of myocardial perfusion, which can be intermittent, acute and sustained, or chronic. These pathologic anomalies may be present from early infancy and can result in angina, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, ventricular aneurysms, or sudden death.

Normal and anomalous coronary arteries have been classified by various criteria. The system proposed by Dr. Angelini in 1988 includes nomenclature and definitions of both normal variations in coronary arteries and anomalous coronary arteries. 1 A consensus report by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons–Congenital Heart Surgery Database Committee uses the following nomenclature to define coronary artery anomalies: 1) anomalous pulmonary origins of the coronaries (APOC), 2) anomalous aortic origins of the coronaries (AAOC), 3) congenital atresia of the left main coronary artery (CALM), 4) coronary arteriovenous fistulae (CAVF), 5) coronary artery bridging (CB), 6) coronary artery aneurysms (CAn), and 7) coronary stenosis. 2 Of these, the 3 most common types of clinically significant coronary artery anomalies that are treated surgically are CAVF, APOC, and AAOC. The surgical techniques used to treat these coronary anomalies have advanced over the last 5 decades, and excellent surgical results have been achieved. Which procedures are best, however, continues to be debated.

We reviewed the surgical management and early outcomes of 178 patients who had undergone surgery for coronary artery anomalies at the Texas Heart Institute from December 1963 through June 2001. Patients with associated cardiac lesions were excluded either when the anomaly was not the primary indication for surgery or when it was not clinically significant. Of the 178 patients, 98 underwent surgery for 108 congenital coronary artery fistulae (CAF)*, another 65 patients underwent surgery for APOC, and 15 patients underwent surgery for AAOC. The patients' ages at the time of operation ranged from 1 month to 71 years. In this review, we discuss historical aspects of the surgical treatment of these anomalies and describe their present-day management.

Congenital Coronary Artery Fistula

Congenital coronary artery fistula is an aberrant connection that originates from a coronary artery and drains into a heart chamber, the pulmonary artery, the coronary sinus, or a pulmonary or central vein. Coronary artery fistulae (CAF) can be single or multiple, and their hemodynamic consequences depend on the site of drainage and the resistance in the fistula. Although most fistulae originate from the right coronary artery (RCA) and terminate in a right-sided heart chamber, the left coronary artery (LCA) or any of its branches may also be the site of origination. A CAF may precipitate right- or left-heart volume overload. In addition, patients may develop clinically significant myocardial ischemia from coronary artery steal, which results from preferential blood flow through the fistula. 3

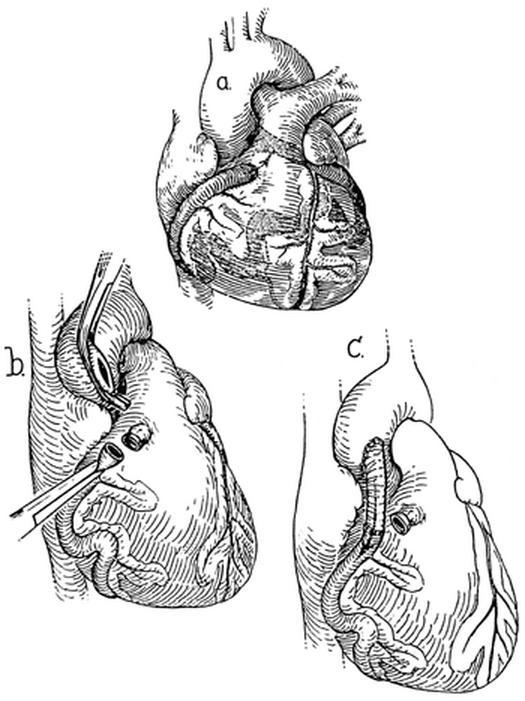

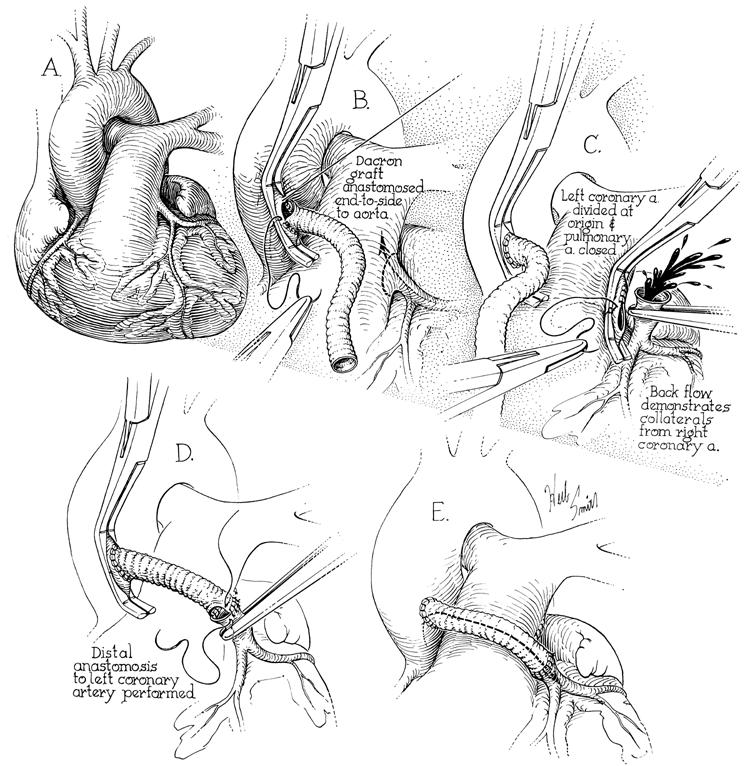

On 23 December 1963, Drs. Hallman and Cooley performed the 1st successful coronary bypass graft procedure on an 8-year-old girl who had a single LCA that terminated in a fistula to the right ventricular outflow tract. 4 A Dacron graft was interposed from the aorta to the distal anomalous coronary artery without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (Fig. 1). The distal end of the fistula was ligated. The single coronary artery was then converted to a 2-coronary system. Follow-up angiography showed a patent graft, and the patient remained asymptomatic for more than 3 decades. Thirty-four years after her bypass, the patient, then 42 years old, developed symptoms of angina and was found to have an occluded graft and subtotal occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD). She underwent successful reoperative coronary artery bypass grafting, with anastomosis of the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) to the LAD. A report about this reoperation, performed 34 years after the 1st successful aortocoronary bypass, has recently been submitted for publication by S. Harfouche and C.H. Hallman.

Fig. 1 First successful repair of a coronary artery fistula using a bypass graft (1963). A) A single left coronary artery terminated in a coronary artery fistula and drained into the right ventricular outflow tract. B) The terminal end was ligated and divided. C) Aortocoronary bypass was performed, with use of a Dacron graft, to create a 2-coronary system.

(From Hallman GL, Cooley DA, Singer DB. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries: anatomy, pathology, and surgical treatment. Surgery 1966;59:133–44. Reprinted with permission from Mosby, Inc.)

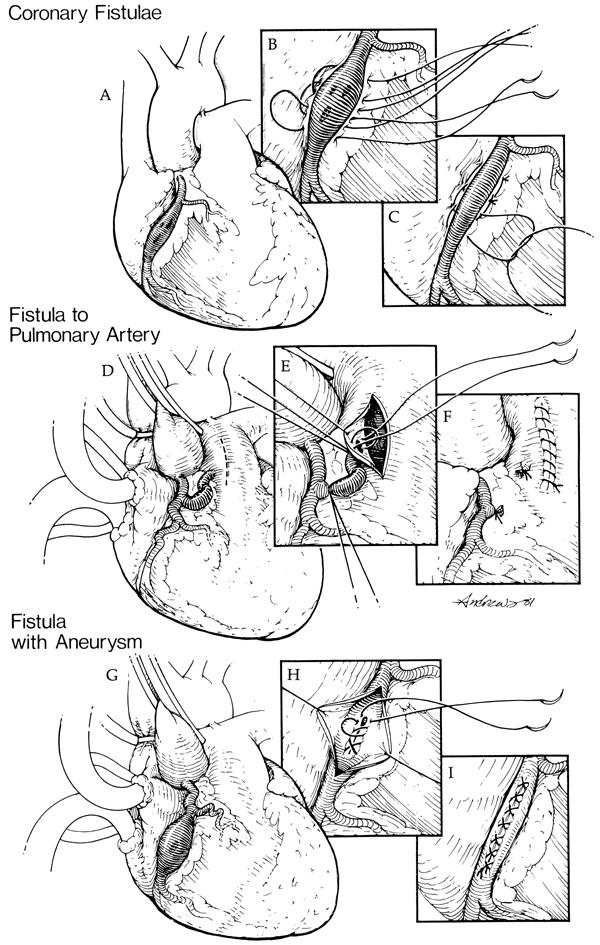

Before the use of coronary bypass, most coronary artery fistulae were either ligated or repaired with a tangential arteriorrhaphy. 5 Ligation alone, however, was associated with complications and high surgical mortality rates. 6,7 Tangential arteriorrhaphy can be performed without cardiopulmonary bypass when the fistula is situated in an easily accessible region of the heart. Multiple horizontal mattress sutures are placed between the coronary artery and the fistula to ligate the fistula without disrupting flow in the feeding coronary artery (Fig. 2 A–C). 8

Fig. 2 Techniques to repair coronary artery fistulae. A) Coronary artery fistulae from the right coronary artery (RCA) to the right ventricle are shown, consisting of multiple openings. B) Multiple horizontal mattress sutures are placed between the artery of origin and the heart. C) The fistulous openings are obliterated while restoring the patency of the RCA. D) Coronary artery fistula from the RCA to the pulmonary artery is shown. E, F) The pulmonary artery is opened, the fistulous opening is identified, and the fistula is ligated from within the pulmonary artery under direct vision. G) Coronary artery fistula from the RCA with an aneurysm is shown. H) The aneurysm is opened and the fistula is repaired from within the aneurysm. I) The aneurysm is plicated.

(From Urrutia-S CO, Falaschi G, Ott DA, Cooley DA. Surgical management of 56 patients with congenital coronary artery fistulas. Ann Thorac Surg 1983;35:300–7. 8 Reprinted with permission from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Illustrations by Bill Andrews.)

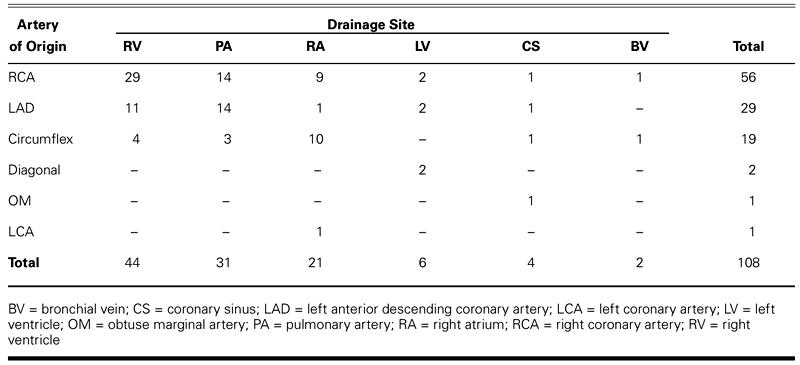

Since 1963, 98 patients have undergone surgery for 108 fistulae at the Texas Heart Institute. Of these patients, 58 had isolated CAF, and 40 had clinically significant fistulae and an associated cardiac lesion, most often coronary artery occlusive disease. Most fistulae drained into a right-sided chamber (100/108), and almost half originated from the right coronary artery (56/108) (Table I). The techniques used to correct the CAF in this series are shown in Table II. Internal closure of the fistula(e) within the receiving chamber or vessel has become the procedure of choice whenever feasible (Fig. 2 D–F). 8 When a fistula is associated with a large aneurysm of the feeding artery, it can be ligated from within the aneurysm, and arterial continuity can be restored by plication and closure of the aneurysm (Fig. 2 G–I). 8

TABLE I. Arteries of Origin and Drainage Sites of 108 Coronary Artery Fistulae in 98 Patients

TABLE II. Surgical Procedures Performed for 108 Coronary Artery Fistulae in 98 Patients

The overall operative mortality rate for repair of CAF was 2.0% (2 of 98 patients) during the 37½-year study period. Of the 58 patients with isolated CAF, there was no early mortality. Of the 40 patients with associated cardiac lesions, 2 died within 30 days of surgery. Both deaths were attributed to the associated cardiac lesions and occurred early in the series. Other complications included myocardial infarction (2), residual fistula (1), cerebrovascular accident (1), mediastinitis (1), complete heart block requiring pacemaker insertion (1), and successfully treated ventricular fibrillation (1).

Anomalous Pulmonary Origins of the Coronaries

When one of the main coronary arteries originates from the pulmonary artery (APOC), myocardial perfusion is dependent on the extent of collateral circulation and, to a lesser degree, on the pulmonary vascular resistance. The myocardium tolerates hypoxia well but does not tolerate low perfusion pressure. If an adequate collateral network is not well established early in infancy when the pulmonary vascular resistance decreases, the myocardium perfused by the anomalous artery will often become ischemic. Patchy areas of fibrosis develop, resulting in ventricular dysfunction and, often, in large ventricular aneurysms, mitral regurgitation, or both. Patients usually present in early infancy in cardiogenic shock. Without surgical intervention, this situation is uniformly fatal.

If the collateral network is well developed by the time the pulmonary vascular resistance falls, however, the region supplied by the anomalous artery is perfused by collaterals from the contralateral artery. The result is a functional single-coronary system that helps some patients remain asymptomatic into early adulthood. Blood flow in the anomalous artery will often become reversed, and preferential blood flow into the low-pressure pulmonary artery can result in coronary steal and angina.

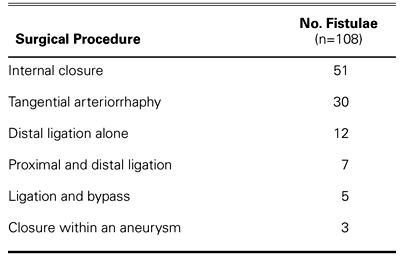

The 1st successful repair for APOC was performed by Sabiston and colleagues in 1960. 9 This operation involved ligation of the anomalous coronary artery where it originated, at the pulmonary artery, which resulted in complete dependency on collateral circulation and in high rates of early mortality. In addition, high rates of late complications were reported after use of this technique. 10–12 In 1965, Dr. Cooley and colleagues operated on a 5-year-old boy who had an anomalous LCA originating from the pulmonary artery. Without the aid of cardiopulmonary bypass, they created a 2-coronary system by connecting a Dacron interposition graft from the aorta to the proximal LCA (Fig. 3). 13 The patient made a full recovery, and follow-up angiography showed a widely patent graft 10 years postoperatively. 14 He remained active and asymptomatic until he died suddenly at age 24 playing soccer—19 years after his bypass surgery. Saphenous vein grafts were used over the next several years with good early results, but long-term follow-up showed patency in only 70%. 15

Fig. 3 The 1st creation of a 2-coronary system for an anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (1965). A) The left coronary artery (LCA) originated from the posterior pulmonary artery. B) A Dacron graft was anastomosed to the aorta using a partial-occlusion clamp. C) The LCA was ligated proximally and divided with strong backflow in the LCA. D) The Dacron graft was anastomosed end-to-end to the LCA. E) The graft was positioned with no tension across the pulmonary artery or on the graft.

(From Cooley DA, Hallman GL, Bloodwell RD. Definitive surgical treatment of anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery: indications and results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1966;52:798–808. 13 Reprinted with permission from Mosby, Inc. Illustrations by Herb Smith.)

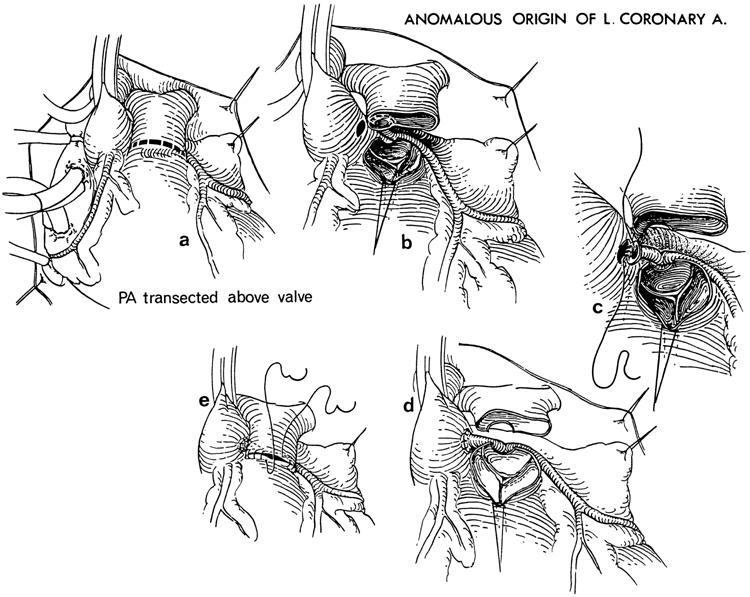

Neches and colleagues 16 first reported the reimplantation of an anomalous LCA from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) into the aorta in 1974. In 1977, Grace, Angelini, and Cooley 12 reported 4 successful cases performed in 1975 and 1976. Today, reimplantation has become the procedure of choice whenever possible. 17 An anomalous RCA from the pulmonary artery is technically easier to transpose onto the aorta than is ALCAPA because of the anterior position of the RCA ostium on the pulmonary artery. During ALCAPA repair, the LCA must be well mobilized to avoid tension or kinking of the coronary artery. The ostium is excised with a button of surrounding pulmonary artery tissue, and the pulmonary artery is often transected. The LCA is then sewn to the left side of the aortic root, ensuring no tension on the artery. The defect in the pulmonary artery is repaired with a pericardial patch (Fig. 4). 12 If the artery cannot be mobilized sufficiently, another option for the repair of ALCAPA is the intrapulmonary tunnel (Takeuchi) procedure. 18 We have performed this procedure in 1 patient with good results, although late supravalvular stenosis and baffle obstruction have been reported by others. 11

Fig. 4 Reimplantation of an anomalous left coronary artery (LCA) from the pulmonary artery onto the aorta. A) The pulmonary artery (PA) is transected above the pulmonary valve. B) The LCA ostium is resected from the pulmonary artery with a button of surrounding pulmonary artery tissue. The LCA is mobilized to the bifurcation. C) The LCA ostium is anastomosed end-to-end to the left side of the aorta. D) The reimplanted LCA is placed posterior to the pulmonary artery and an appropriate tension-free position is ensured. E) The pulmonary artery is closed. (Note: The pulmonary artery is routinely closed with a pericardial patch [not shown].)

(From Grace RR, Angelini P, Cooley DA. Aortic implantation of anomalous left coronary artery arising from pulmonary artery. Am J Cardiol 1977;39:609–13. 12 ©1977. Reprinted with permission from Excerpta Medica Inc.)

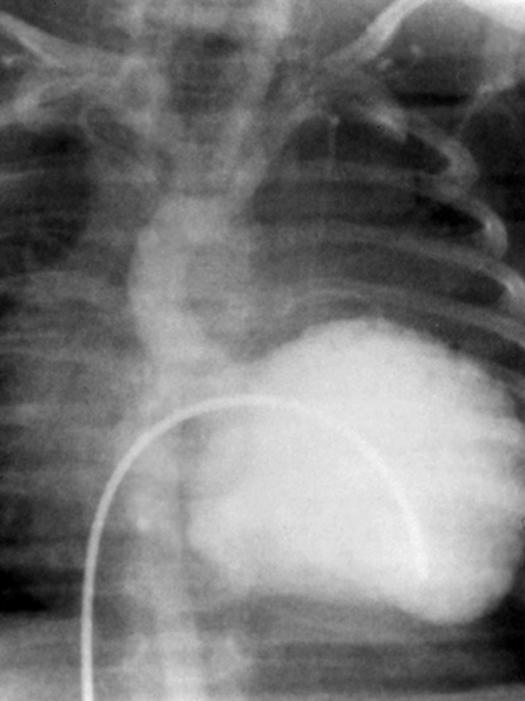

Since 1963, we have operated on 65 patients for APOC. Sixty-two of these patients had ALCAPA, 2 had an anomalous RCA originating from the pulmonary artery, and another patient had an anomalous circumflex artery originating from the right pulmonary artery branch. 19 Most patients (46/65) underwent reimplantation of the anomalous artery into the aorta. Another 16 patients underwent ligation and bypass of the anomalous artery. Early in our experience, 2 patients underwent simple ligation of the LCA at its origin. A Takeuchi intrapulmonary tunnel procedure was performed in 1 patient. The operative mortality rate in this group was 6.2% (4 of 65). Two of the 46 patients who underwent reimplantation of the anomalous artery into the aorta died. Both patients had severe left ventricular failure; one of these was an infant who also had a large left ventricular aneurysm (Fig. 5). Among the 16 patients who underwent bypass procedures, there was 1 early death. One of the 2 patients who underwent simple ligation died. Overall, the operative mortality rate was dependent on the extent of irreversible left ventricular dysfunction.

Fig. 5 Preoperative left ventriculogram of an infant with ALCAPA and an extensive left ventricular aneurysm. This patient presented in cardiogenic shock and underwent emergency reimplantation of the left coronary artery onto the aorta and resection of the left ventricular aneurysm.

Anomalous Aortic Origins of the Coronaries

Anomalous origin of the right or left coronary artery (AAOC) from the contralateral sinus of Valsalva is often completely asymptomatic; however, some patients, particularly young athletes, present with exertional angina or sudden death. The pathophysiology of these anomalies is complex and controversial, creating debate over the indications for surgery and the choice of surgical techniques. 20 The proximal portion of the anomalous coronary artery often exits the aorta at an acute angle, creating functional or actual stenosis of the ostium. The proximal portion of the AAOC can also course between the roots of the aorta and pulmonary artery. Impingement of the anomalous coronary artery during exertion (caused by pressure and volume expansion of the pulmonary artery against the aorta) has been proposed as a possible mechanism of malperfusion. 21 In addition, the proximal anomalous artery may course through the wall of the aorta for a variable distance, resulting in narrowing of the lumen. 22 The surgeon must consider these anatomic variations to choose the appropriate intervention.

In our series, 15 patients, all with exertional angina, underwent surgery for AAOC. In 8 of these patients, the RCA originated from the left sinus of Valsalva. In only 2, the anomalous artery coursed between the aorta and the pulmonary artery, as was determined by either surgical exploration or coronary angiography, or, more recently, by magnetic resonance angiography. In 4 of the patients, the anomalous coronary artery was reimplanted to the ipsilateral sinus of Valsalva. Three other patients underwent ligation of the anomalous artery and bypass with a saphenous vein graft. One of these patients had presented with recurrent exertional angina 1 month after undergoing bypass at another hospital. The right internal mammary artery (RIMA) had been used in that procedure, without ligation of the RCA. Coronary angiography at our institution showed occlusion of the RIMA graft. Reoperation involved ligation of the RCA and bypass using a saphenous vein graft to the RCA. The patient has subsequently remained symptom free. Another patient who underwent bypass grafting with the RIMA and without ligation of the anomalous RCA has remained free of exertional angina.

In 7 of the 15 patients with AAOC, the LCA or circumflex branch originated from the right sinus of Valsalva. In 3 of these patients, the left main coronary artery originated from the right sinus of Valsalva. All underwent bypass grafting, with anastomosis of the LIMA to the LAD artery. One of these patients also had a RIMA graft anastomosed to the circumflex branch, and another had a saphenous vein graft anastomosed to the circumflex branch and concomitant mitral valve repair. One patient experienced atypical chest pain 1 month postoperatively; however, coronary angiography showed a widely patent LIMA graft and patent native vessels. In 4 other patients, the circumflex branch originated from the right sinus of Valsalva; they had exertional angina and no significant coronary artery atherosclerotic lesions. Two of these patients also had circumflex ostial stenosis and underwent aortocoronary bypass with saphenous vein grafts to the obtuse marginal branches. The other 2 patients (without ostial stenosis) underwent ligation of the circumflex artery and bypass with a saphenous vein graft. There were no deaths, and follow-up coronary angiography showed no graft failure.

Discussion

We reviewed the surgical procedures and early outcomes of 178 pediatric and adult patients undergoing surgical intervention for CAF, APOC, or AAOC. Each of these anomalies can remain latent for years, or they can present with devastating clinical consequences, regardless of the age of the patient. Surgical techniques have evolved over the past 38 years, and the specific procedures used to correct each type of anomaly vary, depending on individual patient conditions and characteristics.

Patients with hemodynamically significant or symptomatic CAF should undergo intervention to obliterate the fistulous tract. The goal of intervention is to interrupt the fistulous connection without disrupting blood flow within the feeding coronary artery. Careful evaluation of the anomalous artery is important to identify ectatic coronary arteries, which are prone to mural thrombus formation. Simple ligation should be limited to fistulae from terminal coronary branches only. Ligation and bypass can be performed with or without cardiopulmonary bypass. Tangential arteriorrhaphy does not require cardiopulmonary bypass and is indicated only for lateral and easily accessible fistulae; even so, this procedure may injure the feeding coronary artery, or result in residual or missed fistulae. Internal closure from within the receiving chamber is the procedure of choice in most cases, because the fistula(e) can be closed under direct vision, ensuring complete obliteration of all fistulous openings into the chamber. After ligation, blood cardioplegia can be administered via the coronary arteries to identify any missed openings.

Patients diagnosed with APOC should undergo surgery to restore a 2-coronary system. The 1st goal of intervention is to improve coronary perfusion pressure in the area of myocardium supplied by the arterial system (originating from the pulmonary artery) and to relieve coronary steal by interrupting flow into the low-pressure pulmonary artery. The 2nd goal is to provide a reliable, durable conduit. Use of either Dacron or saphenous vein grafts for bypass and ligation of the proximal LCA has resulted in good early and long-term survival in many patients, although occlusion or stenosis has been reported in 30% of the saphenous vein grafts. 15 In addition, saphenous grafts may have limited use in very young patients due to the lack of growth potential. Reimplantation of the anomalous artery has become our procedure of choice. The LCA can almost always be mobilized to reach the aorta without tension. Moreover, reimplantation of the artery into the aorta can be performed safely, and it restores a 2-coronary system. The outcome depends on the extent of irreversibly damaged myocardium. Others 23,24 have reported excellent early and long-term results with this procedure, including the recovery of severely remodeled ventricles.

Surgical indications for AAOC are more controversial. The most common patient presentation in our series was exertional angina, but frequently, such patients present with sudden death. The goal of intervention for AAOC is to provide reliable perfusion to the anomalous arterial system beyond the site or sites of potential arterial obstruction. In some patients, the obstruction may be limited to a stenotic ostium, whereas other patients may have external forces acting several centimeters distally. If the anatomy of the anomalous artery is favorable, excision of the ostium with a button of surrounding aorta and subsequent reimplantation onto the aorta is an appropriate procedure.

Although most of the patients in our series underwent bypass procedures, the choice of bypass conduits remains a source of debate. Most patients presenting with AAOC are young and otherwise healthy; therefore, the chosen conduit must provide the best potential long-term patency when used to bypass a nonoccluded artery. Some authors 25,26 advocate the use of internal mammary arteries for the treatment of coronary artery occlusive disease and coronary artery anomalies because of their long-term patency advantage over vein grafts. Others 25 advocate the use of vein grafts to avoid the early occlusion and stenosis that can occur in arterial grafts that are used to bypass vessels with competitive flow. Another difficult decision to be made is whether to ligate a patent anomalous artery in order to eliminate competitive flow.

In our series, we used saphenous veins and internal mammary arteries as conduits—with or without ligation of the anomalous artery—for AAOC. The 1 patient from an outside hospital who presented with early occlusion of a RIMA graft anastomosed to the anomalous RCA from the left sinus of Valsalva provides only anecdotal evidence. All of the internal mammary artery grafts in our series were implanted recently, and there have been no early occlusions; long-term follow-up is ongoing.

In summary, techniques for patients undergoing surgical intervention for coronary artery fistulae, anomalous pulmonary origins of the coronaries, and anomalous aortic origins of the coronaries have progressed over time. Although the specific procedures used to correct each type of anomaly will vary for each patient, our experience shows that certain guidelines can be applied to optimize outcomes.

Footnotes

*In this review, we will use the term coronary artery fistula instead of coronary arteriovenous fistula (CAVF) because fistulae may also drain into nonvenous chambers.

Address for reprints: Ross M. Reul, MD, Texas Heart Institute, P.O. Box 20345, Houston, TX 77225-0345

This paper has its basis in a presentation made at the symposium Coronary Artery Anomalies: Morphogenesis, Morphology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Correlations, held on 28 Feb.–1 March 2002, at the Texas Hear® Institute, Houston, Texas.

References

- 1.Angelini P. Normal and anomalous coronary arteries: definitions and classification. Am Heart J 1989;117:418–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Dodge-Khatami A, Mavroudis C, Baker CL. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: anomalies of the coronary arteries. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69(4 Suppl):S270–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Levin DC. Anomalies and anatomic variations of the coronary arteries. In: Baum S, editor. Abrams' angiography: vascular and interventional radiology. 4th ed. Boston: Little, Brown; 1997. p. 740–55.

- 4.Hallman GL, Cooley DA, McNamara DG, Latson JR. Single left coronary artery with fistula to right ventricle. Reconstruction of two-coronary system with Dacron graft. Circulation 1965;32:293–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cooley DA, Ellis PR Jr. Surgical considerations of coronary arterial fistula. Am J Cardiol 1962;10:467–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Liotta D, Hallman GL, Hall RJ, Cooley DA. Surgical treatment of congenital coronary artery fistula. Surgery 1971;70:856–64. [PubMed]

- 7.Cheung DL, Au WK, Cheung HH, Chiu CS, Lee WT. Coronary artery fistulas: long-term results of surgical correction. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;71:190–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Urrutia-S CO, Falaschi G, Ott DA, Cooley DA. Surgical management of 56 patients with congenital coronary artery fistulas. Ann Thorac Surg 1983;35:300–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Sabiston DC Jr, Neill CA, Taussig HB. The direction of blood flow in anomalous left coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery. Circulation 1960;22:591–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Backer CL, Stout MJ, Zales VR, Muster AJ, Weigel TJ, Idriss FS, Mavroudis C. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery. A twenty-year review of surgical management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992;103:1049–58. [PubMed]

- 11.Wilson CL, Dlabal PW, Holeyfield RW, Akins CW, Knauf DG. Anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery. Case report and review of literature concerning teen-agers and adults. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1977;73:887–93. [PubMed]

- 12.Grace RR, Angelini P, Cooley DA. Aortic implantation of anomalous left coronary artery arising from pulmonary artery. Am J Cardiol 1977;39:609–13. [PubMed]

- 13.Cooley DA, Hallman GL, Bloodwell RD. Definitive surgical treatment of anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery: indications and results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1966;52:798–808. [PubMed]

- 14.Leachman RD, Zamalloa O, Tapia F, Hallman GL, Cooley DA. Reconstruction with a Dacron tube graft of an anomalous left main coronary artery arising from the pulmonary trunk with 19-year asymptomatic period thereafter. Am J Cardiol 1988;61:195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.el-Said GM, Ruzyllo W, Williams RL, Mullins CE, Hallman GL, Cooley DA, McNamara DG. Early and late result of saphenous vein graft for anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery. Circulation 1973;48(1 Suppl):III2–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Neches WH, Mathews RA, Park SC, Lenox CC, Zuberbuhler JR, Siewers RD, Bahnson HT. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. A new method of surgical repair. Circulation 1974;50:582–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Fagan TE, Palacios-Macedo A, Nihill MR, Fraser CD Jr, Cooley DA. Coronary artery anomalies in pediatric patients. In: Angelini P, editor. Coronary artery anomalies: a comprehensive approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. p. 151–71.

- 18.Takeuchi S, Imamura H, Katsumoto K, Hayashi I, Katohgi T, Yozu R, et al. New surgical method for repair of anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1979;78:7–11. [PubMed]

- 19.Ott DA, Cooley DA, Pinsky WW, Mullins CE. Anomalous origin of circumflex coronary artery from right pulmonary artery: report of a rare anomaly. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1978;76:190–4. [PubMed]

- 20.Taylor AJ, Byers JP, Cheitlin MD, Virmani R. Anomalous right or left coronary artery from the contralateral coronary sinus: “high-risk” abnormalities in the initial coronary artery course and heterogeneous clinical outcomes. Am Heart J 1997;133:428–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Bloomfield P, Erhlich C, Folland ED, Bianco JA, Tow DE, Parisi AF. Anomalous right coronary artery: a surgically correctable cause of angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 1983;51:1235–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Taylor AJ, Rogan KM, Virmani R. Sudden cardiac death associated with isolated congenital coronary artery anomalies. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:640–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Levitsky S, van der Horst RL, Hastreiter AR, Fisher EA. Anomalous left coronary artery in the infant: recovery of ventricular function following early direct aortic implantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1980;79:598–602. [PubMed]

- 24.Vouhe PR, Baillot-Vernant F, Trinquet F, Sidi D, de Geeter B, Khoury W, et al. Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery in infants. Which operation? When? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1987;94:192–9. [PubMed]

- 25.Cohen AJ, Grishkin BA, Helsel RA, Head HD. Surgical therapy in the management of coronary anomalies: emphasis on utility of internal mammary artery grafts. Ann Thorac Surg 1989;47:630–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Kitamura S, Kawachi K, Nishii T, Taniguchi S, Inoue K, Mizuguchi K, Fukutomi M. Internal thoracic artery grafting for congenital coronary malformations. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;53:513–6. [DOI] [PubMed]