Abstract

Entrapment and fracture of coronary angioplasty hardware are rare complications of percutaneous coronary artery interventions; however, when such incidents occur, they frequently require surgical management. Percutaneous retrieval should be attempted before surgical retrieval unless hemodynamic stability is a problem. Surgical intervention should focus on grafting the affected coronary vessel(s) and ensuring that there is no hardware in the aortic root that could serve as a nidus for thrombus formation. We present 3 cases from our recent experiences of entrapped, fractured hardware. (Tex Heart Inst J 2002;29:329–32)

Key words: Angioplasty, transluminal, percutaneous coronary/adverse effects/instrumentation; coronary artery bypass; coronary vessels; equipment failure; foreign bodies/diagnosis/therapy; heart catheterization/instrumentation

Entrapment and fracture of coronary angioplasty hardware are described complications of percutaneous coronary artery interventional procedures. 1–20 Percutaneous methods of retrieval are often successful; 1–8 however, in half of the reported patients in whom intervention was performed, surgery was required. 7–19 Herein, we report 3 recent cases from 1999–2000 and offer an approach for surgical management.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 78-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and supraventricular tachycardia presented at our institution with severe chest pain of acute onset and shortness of breath. An electrocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy and S-T segment depression in the inferolateral leads. Myocardial infarction was ruled out by serial cardiac enzyme assays.

Diagnostic cardiac catheterization showed an 85% to 90% stenotic lesion in the mid-segment of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and a 90% to 95% stenotic lesion in the proximal 1st diagonal branch. Left ventriculography yielded normal results with an estimated ejection fraction of 0.60. Angioplasty and stenting were performed in the LAD without incident. After stent deployment, it was noted that a slight depression remained in the mid-portion of the balloon. A 2nd inflation was performed, and the catheter was withdrawn. A repeat angiogram revealed severe dye extravasation from the mid LAD just distal to the stented segment. Shortly thereafter, the patient became hypotensive, and chest compressions were started. A reperfusion catheter was passed through the LAD and inflated at the site of the rupture. When initial pericardiocentesis proved ineffective, assistance was requested from the cardiothoracic surgery department. An emergency thoracotomy and pericardial decompression were performed in the catheterization laboratory. The patient was then taken to the operating room.

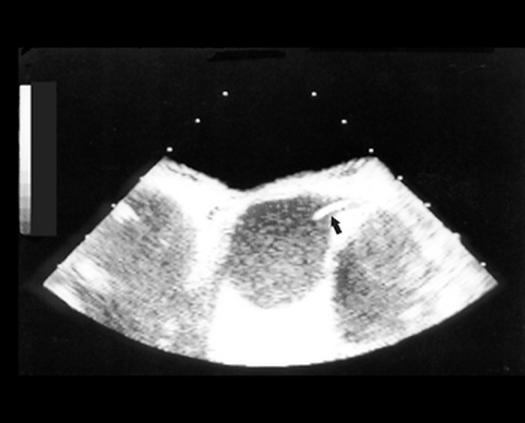

In the operating room, we found the LAD to be ruptured near the apex. The LAD and a diagonal branch were bypassed. Postoperatively, the patient was hypotensive; therefore, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was performed on the 2nd postoperative day. The left ventricle showed segmental dysfunction in the distribution of the LAD. A linear echodensity was found in the ascending aorta, which suggested the presence of a foreign body (Fig. 1). Subsequent catheterization revealed a remnant of the reperfusion balloon within the mid-segment of the stent, extending proximally into the ascending aorta. Attempts at ensnaring the wire were unsuccessful. Because of the patient's overall condition, we decided to pursue conservative management until her clinical status stabilized enough for a 2nd operation.

Fig. 1 Patient 1. Transesophageal echocardiogram of the distal end of a fractured, retained guidewire (arrow) extruding from the left coronary ostium.

Two weeks later, the patient underwent surgical exploration of the mediastinum. The aorta was opened and the catheter remnant was retrieved with minimal effort. After a long, complicated recovery, the patient was discharged from the hospital on the 60th postoperative day.

Patient 2

A 31-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented with unstable angina. She showed no evidence of a myocardial infarction; however, she did have a positive stress test.

Follow-up cardiac catheterization showed a long, 90% stenotic lesion of the proximal LAD; the other vessels were free of disease. Angioplasty and stent placement were performed without incident. Following stent placement, the ostium of the 1st diagonal branch, which arose from the stented segment, was thought to be partially occluded. Balloon angioplasty was then performed, with subsequent entrapment of the dilation catheter within the stent. The cardiothoracic surgery service was consulted on an emergency basis, after which the patient was taken to the operating room for retrieval of the catheter and coronary artery bypass grafting.

The balloon catheter was divided, and the distal end was retrieved through an arteriotomy in the diagonal branch. The remainder of the catheter was removed through the femoral introducer site. The patient then underwent bypass grafting of the diagonal branch and the LAD.

The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged from the hospital on the 6th postoperative day.

Patient 3

A 50-year-old man presented with a syncopal episode and was found to be in complete heart block with an acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. The patient was treated with eptifibatide and heparin and taken for emergency cardiac catheterization.

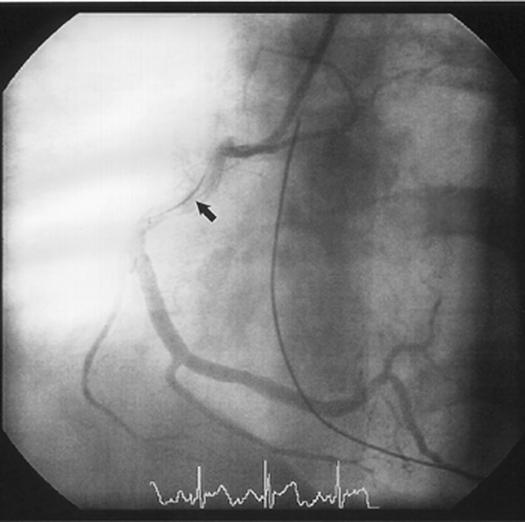

Catheterization showed 20% narrowing of the LAD and a 99% stenotic lesion of the right coronary artery (RCA) just proximal to the 1st acute marginal branch. Other vessels were free of disease. The patient underwent angioplasty and stenting of the RCA. The initial deployment of the stent proceeded without incident; however, repeat angiography revealed residual stenosis in the proximal portion of the stent. An attempt was made to recross the stenotic portion of the vessel with the stent, but the wire doubled over and became lodged in the strut. Attempts to withdraw the wire resulted in the fracture of the wire in the proximal RCA (Fig. 2). The cardiothoracic surgery service was contacted for an emergency consultation.

Fig. 2 Patient 3. Angiogram shows an entrapped, fractured guidewire (arrow) within the right coronary artery.

The patient was taken to the operating room on an emergency basis, and coronary artery bypass grafting of the posterior descending artery and a large acute marginal branch was performed. Intraoperative TEE revealed a linear density within the aortic root. An aortotomy revealed the distal end of the guidewire within the right coronary ostium. The guidewire was very firmly lodged in the RCA, and moving it resulted in retraction of the area of the RCA in the atrioventricular groove. The guidewire was therefore clipped off deep within the right coronary ostium.

The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged from the hospital on the 4th postoperative day.

Discussion

Retained hardware within the coronary circulatory system presents a unique set of problems. The reported incidence of entrapment or fragmentation of such devices during or after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty ranges from 0.2% to 0.8%. 6,7,19 A search of the world medical literature revealed just 36 reported cases in the past 13 years. In 8 cases, the wire fragments were left in situ without further intervention, due to either poor general medical condition of the patient or total containment of the wire within the coronary circulation. In general, the patients did well if the wire was trapped within an occluded vessel. Follow-up studies reported no migration of the entrapped hardware. 6,7,20 Various percutaneous retrieval techniques were successful in 14 cases. 1–8 Surgical intervention was required in another 14 cases, with aortocoronary bypass necessary on the affected vessel in 13 cases. 7–19

In our opinion, hardware retained intraluminally within a coronary vessel will generally serve as a nidus for endothelial injury and platelet deposition, putting the vessel at risk for acute thrombosis. When a wire or catheter is trapped, vigorous efforts at percutaneous removal are sometimes attempted before a thoracic surgeon is contacted. These attempts create further risk to the endothelium of an already diseased vessel. Therefore, when possible, we advocate removal of the wire or catheter and downstream grafting of the coronary artery unless it can be ascertained that the vessel is otherwise unharmed.

Identifying the full extent of a fractured guidewire can be difficult fluoroscopically but is particularly important if the wire extrudes into the ostium and aorta. The distal end of the wire might not be evident to an operating thoracic surgeon grafting the vessel in a disease-free area. If foreign material remains in the aortic root, it can serve as a thrombogenic source and put the patient at risk for systemic embolic events, including cerebrovascular accidents.

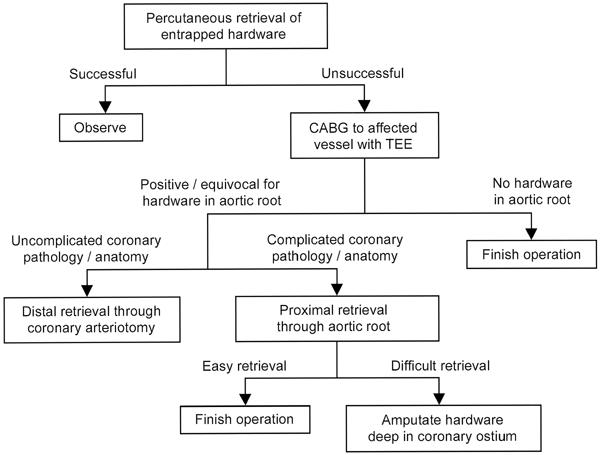

Therefore, we propose an algorithm for managing these patients (Fig. 3). Once it has been established that some portion of hardware is entrapped in the coronary system, attempts should be made to remove the device percutaneously. If these efforts are unsuccessful, surgical intervention should be undertaken. On the basis of our collective experience, we propose the following approach to the surgical management of patients with a retained guidewire or catheter fragments. Coronary bypass of the affected vessel should be undertaken. Surgical intervention should be accompanied by TEE to evaluate the distal extent of the wire or catheter. This method is useful in locating the end of the wire in the aortic root and the proximal aorta. If the results are positive or equivocal, the aortic root should be opened and explored. If the retained wire or catheter cannot be easily removed, it should be trimmed as high as possible within the coronary ostium in order to prevent future thrombus formation and possible systemic embolization. Alternatively, the wire can be retrieved distally through an arteriotomy; however, this approach is not always straightforward due to the presence of atherosclerotic disease, or stents, and to the prospect of further injury to the vessel.

Fig. 3 Algorithm for managing entrapped percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty hardware.

CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; TEE = transesophageal echocardiography

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Te-Ming Tommy Chang, MD, 1617 Owen Drive, Fayetteville, NC 28304

Dr. Chang is currently on active staff at Cape Fear Valley Medical Center, Fayetteville, North Carolina. Dr. Pellegrini is currently at the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Gurley JC, Booth DC, Hixson C, Smith MD. Removal of retained intracoronary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty equipment by a percutaneous twin guidewire method. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1990;19:251–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Krone RJ. Successful percutaneous removal of retained broken coronary angioplasty guidewire. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1986;12:409–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Savas V, Schreiber T, O'Neill W. Percutaneous extraction of fractured guidewire from distal right coronary artery. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1991;22:124–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Serota H, Deligonul U, Lew B, Kern MJ, Aguirre F, Vandormael M. Improved method for transcatheter retrieval of intracoronary detached angioplasty guidewire segments. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1989;17:248–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Yeon EB, Cemaletin NS, Moses JW, McCrossan J. Successful percutaneous removal of retained probe balloon wire during coronary angioplasty. Am Heart J 1990;119:1201–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hartzler GO, Rutherford BD, McConahay DR. Retained percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty equipment components and their management. Am J Cardiol 1987;60:1260–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lotan C, Hasin Y, Stone D, Meyers S, Applebaum A, Gotsman MS. Guide wire entrapment during PTCA: a potentially dangerous complication. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1987:13:309–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Arce-Gonzalez JM, Schwartz L, Ganassin L, Henderson M, Aldridge H. Complications associated with the guide wire in percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 1987;10:218–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bachenheimer LC, Green CE, Rosing DR, Wallace RB. Surgical removal of the intracoronary portion of a fractured angioplasty guidewire. Am J Cardiol 1988;61:946–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Breisblatt WM. Inflated balloon entrapped in a calcified coronary stenosis. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1993;29:224–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Doring V, Hamm C. Delayed surgical removal of a guide-wire fragment following coronary angioplasty. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990;38:36–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ghosh PK, Alber G, Schistek R, Unger F. Rupture of guide wire during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989;97:467–9. [PubMed]

- 13.Khonsari S, Livermore J, Mahrer P, Magnusson P. Fracture and dislodgment of floppy guidewire during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 1986;58:855–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Maat L, van Herwerden LA, van den Brand M, Bos E. An unusual problem during surgical removal of a broken guidewire. Ann Thorac Surg 1991;51:829–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Proctor MS, Koch LV. Surgical removal of guidewire fragment following transluminal coronary angioplasty. Ann Thorac Surg 1988;45:678–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sethi GK, Ferguson TB Jr, Miller G, Scott SM. Entrapment of broken guidewire in the left main coronary artery during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Ann Thorac Surg 1989;47:455–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Stellin G, Ramondo A, Bortolotti U. Guidewire fracture: an unusual complication of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol 1987;17:339–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Vrolix M, Vanhaecke J, Piessens J, De Geest H. An unusual case of guide wire fracture during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1988;15:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Steffenino G, Meier B, Finci L, Velebit V, von Segesser L, Faidutti B, Rutishauser W. Acute complications of elective coronary angioplasty: a review of 500 consecutive procedures. Br Heart J 1988;59:151–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Doorey AJ, Stillabower M. Fractured and retained guide-wire fragment during coronary angioplasty—unforeseen late sequelae. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1990;20:238–40. [DOI] [PubMed]