To the Editor:

In their historical review paper “Cardiology's 10 Greatest Discoveries of the 20th Century,” Mehta and Khan state, “Vasilii Kolesov, a Russian cardiac surgeon, performed the 1st internal mammary artery–coronary artery anastomosis” in 1964. 1

The 1st successful coronary artery bypass operation (anastomosis) was performed on 2 May 1960 by Robert H. Goetz at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Bronx Municipal Hospital Center. 2

This case was mentioned in an addendum to a report of coronary artery anastomoses in dogs, 2 and has been cited by others, including Kolesov, 3 as the 1st successful human coronary artery bypass. 4–10 However, Goetz's case has also frequently been overlooked. Confusion has persisted for over 40 years and seems to be due to the absence of a full report and to misunderstanding about the type of anastomosis that was created. The anastomosis was intima-to-intima, with the vessels held together with circumferential ligatures over a specially designed metal ring.

Kolesov did the 1st successful coronary bypass using a standard suture technique in 1964, and over the next 5 years he performed 33 sutured and mechanically stapled anastomoses in St. Petersburg, Russia. 11

At the time that Goetz planned this operation, the understanding of coronary artery insufficiency was considerably different from today's understanding. Despite many innovative efforts, surgical results were generally considered unsuccessful, and the very concept of surgical revascularization was in doubt. Selective coronary angiography and extracorporeal bypass were still under development. Due to these limitations, coronary revascularization was attempted using techniques that could be done quickly and without heart-lung bypass.

Goetz reasoned that a coronary artery bypass operation could be performed safely if the patient had a complete obstruction and a patent distal vessel. The concept of reduced flow with viable but ischemic muscle beyond was just becoming understood. The suggestion that a bypass operation could help selected patients precipitated an immediate and spirited controversy within the institution, with most members of the medical department vehemently opposed.

The procedure was done without extracorporeal support. Dr. Goetz completed the anastomosis in 17 seconds (Drs. Rohman, Haller, and Dee assisting); the postoperative course was uneventful. An angiogram on the 14th day showed the anastomosis to be patent. The patient resumed work as a taxi driver and was free from angina for approximately 1 year. He died of an acute posterior myocardial infarction on 23 June 1961, more than 13 months after surgery (not 8, as stated elsewhere).

Contrary to other reports, a limited autopsy was performed. The heart, with the anastomosis, was provided to Dr. Goetz. One of us (JDH) assisted him in performing angiograms of this specimen. The anastomosis was well healed and patent. There was an obstruction at the origin of the internal mammary from the subclavian; several large intercostal branches filled the distal internal mammary, kept the anastomosis patent, and provided blood to the heart. Despite the patent anastomosis and improvement of symptoms, we can attest to statements in Dr. Goetz's letter to Konstantinov 9,10 that resentment persisted not only in the cardiology department, but in the surgery department.

Shortly afterwards, all records—the hospital chart, angiograms, specimens, and photographs—disappeared and were never found. Dr. Goetz decided that since documentation was no longer possible, it was just as well to omit the autopsy finding.*

At a subsequent (circa 1968) meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, permission to present this case—within the context of a discussion of reports by others on coronary angiography and bypass surgery—was denied, with commentary by the society's president and secretary that the subject of coronary artery surgery was unimportant and would soon be forgotten. In 1967, similar statements from Russian cardiologic and surgical societies had appeared alongside Kolesov's report. 9,10

Dr. Goetz was a kind and considerate man, very much concerned with the welfare of his family, his patients, and his students. His manner, however, remained very formal, official, and direct. He did not take time for foolishness or incompetence. His German accent seemed to become more pronounced through the years, although he spoke only English after he and his wife left Europe. He had a very wry and active sense of humor that was usually accompanied by an infectious gleam in his eye. He always saw the lighter side of otherwise depressing situations. Perhaps this aspect of his personality helped to provide him the strength to carry on.

In addition to his many accomplishments cited by others, 4,5,9,10 Goetz was one of the 1st big-game hunters to use a muscle relaxant to capture wild animals alive (giraffes) for study.** This method soon became the standard. He invented one of the most popular parlor games of the time, played with dice on a board. After the end of World War II, he was reconciled with a brother who had been conscripted into the German army. In Cape Town, Goetz was a Fellow in the Royal College of Physicians (FRCP). In the United States, he became a Fellow in the American College of Surgery (FACS). The Einstein faculty and staff later showed Goetz their appreciation and respect by electing him president of the faculty. In 1982, at age 72, he retired from surgery and bred prize-winning bulls as a hobby.

Konstantinov's paper on Goetz 9 was reprinted in the Einstein Quarterly Journal in 2001, 10 with the following editorial comments by Lloyd Fricker: “The coronary artery bypass operation is one of the most important surgical advances of the last 50 years. The history of this procedure is a fascinating reflection on the strengths and weaknesses of medical research…. The project was dropped because of the strong negative sentiment from Dr. Goetz's colleagues…. This lack of vision is still very much alive….” 12

Robert Goetz died on 15 December 2000 at age 90, in Scarsdale, New York.

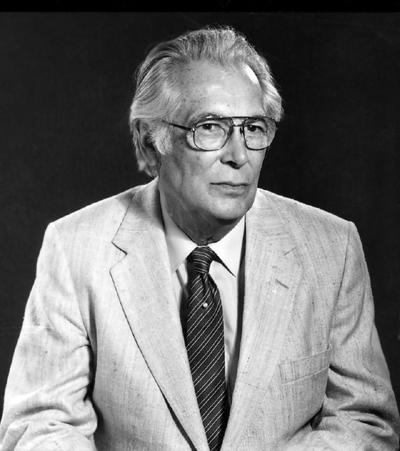

Figure. Dr. Robert H. Goetz

(Photograph courtesy of Sylvia Perle-Goetz and Angela Goetz. From: Konstantinov IE. Robert H. Goetz: the surgeon who performed the first successful clinical coronary artery bypass operation. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:1966–72. 9 Reprinted by permission of Elsevier Science Ltd.)

Footnotes

*Goetz RH to Konstantinov IE (1999–2000), Haller JD (1984–1994), Olearchyk AS (1985–1988). Multiple personal communications.

**His interest in giraffes concerned their regulation of blood pressure—specifically their ability to lift their heads from the ground to full height without fainting.

References

- 1.Mehta NJ, Khan IA. Cardiology's 10 greatest discoveries of the 20th century. Tex Heart Inst J 2002;29:164–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Goetz RE, Rohman M, Haller JD, Dee R, Rosenak SS. Internal mammary-coronary artery anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1961;41:378. [PubMed]

- 3.Kolesov VI, Potashov LV. Surgery of coronary arteries [in Russian]. Eksp Khir Anesteziol 1965;10(2):3–8. [PubMed]

- 4.Olearchyk AS. Coronary revascularization: past, present and future. J Ukr Med Assoc North Am 1988:1(117):3–34.

- 5.Olearchyk AS, Olearchyk RM. Reminiscences of Vasilii I. Kolesov. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67(1):273–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Glenn WW. Some reflections on the coronary bypass operation. Circulation 1972;45:869–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ochsner JL, Mills NL. Coronary artery surgery. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1978.

- 8.Cushing WJ, Magovern GJ, Olearchyk AS. Internal mammary artery graft: retrospective report with 17 years' survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1986:92:963–4. [PubMed]

- 9.Konstantinov IE. Robert H. Goetz: the surgeon who performed the first successful clinical coronary artery bypass operation. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:1966–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Konstantinov IE. Robert H. Goetz: the surgeon who performed the first successful clinical coronary artery bypass operation. Einstein Q J Biol Med 2000;18:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kolesov VI, Kolesov EV. Twenty years' results with internal thoracic artery-coronary artery anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;101:360–1. [PubMed]

- 12.Fricker LD. Cover to cover: In this issue. Einstein Q J Biol Med 2000:18:53.