Abstract

Background

Although new endoscopic techniques can enhance the ability to detect a suspicious lung lesion, the primary diagnosis still depends on subjective visual assessment. We evaluated whether thermal heterogeneity of solid tumors, in bronchial epithelium, constitutes an additional marker for the diagnosis of benign and malignant lesions.

Methods

A new method, developed in our institute, is introduced in order to detect temperature in human pulmonary epithelium, in vivo. This method is based on a thermography catheter, which passes the biopsy channel of the fiber optic bronchoscope. We calculated the temperature differences (ΔT) between the lesion and a normal bronchial epithelium area on 22 lesions of 20 subjects, 50 – 65 years old.

Results

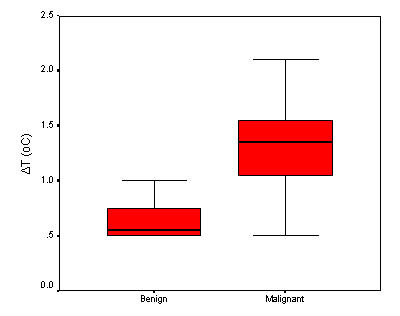

Eleven lesions were benign and 11 were malignant, according to the biopsy histology followed the thermography procedure. We found significant differences of ÄT between patients with benign and malignant tumor (0.71 ± 0.6 vs. 1.23 ± 0.4°C, p < 0.05). Logistic regression analysis showed that 1-Celsius degree differences between normal tissue and suspicious lesion six-fold the probability of malignancy (odds ratio = 6.18, 95% CI 0.89 – 42.7). Also, ΔT values greater than 1.05°C, constitutes a crucial point for the discrimination of malignancy, in bronchial epithelium, with sensitivity (64%) and specificity (91%).

Conclusion

These findings suggest that the calculated ΔT between normal tissue and a neoplastic area could be a useful criterion for the diagnosis of malignancy in tumors of lung lesions.

Background

Each year, primary carcinoma of the lung affects more than 150,000 persons in the United States, making it a major health problem and the leading cause of cancer [1]. Usually the clinical diagnosis of the type of lesion (inflammatory, malignancy) is made, with direct fiberoptic bronchoscopic examination and the suspicious tissue evaluation through histological biopsy. Although new endoscopic techniques, including chromoscopy, fluorescence, scattering and Raman spectroscopies, optical coherence tomography, ultrasound and isotope scanning can enhance the clinical endoscopist's ability to detect a suspicious lung lesion, the primary diagnosis still depends on subjective visual assessment [2]. Some investigators have reported temperature measurement of a suspicious area and even a balloon catheter technique has been introduced for mediastinal temperature in the azygos vein during hyperthermic cancer treatment with rather accurate results [3]. However, till today there has not been introduced an easy, safe technique that can increase the diagnostic ability of the bronchoscopic procedure.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the existence of thermal heterogeneity in bronchial lesions, in vivo, and to test the hypothesis whether there is any thermal distinction between benign, and malignant lung lesions.

Methods

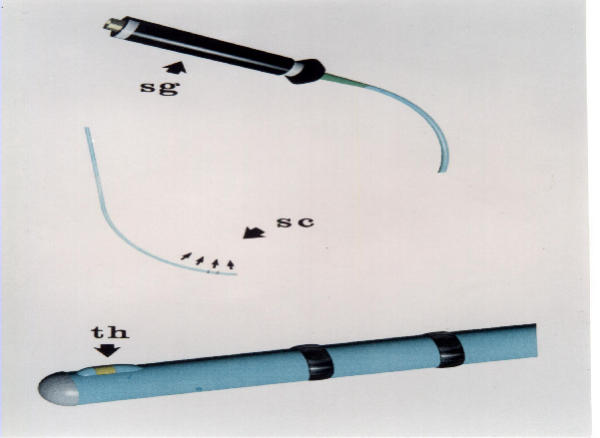

A clinical study was conducted for the purposes described above. A thermography catheter was applied in 20 consecutive subjects who underwent bronchoscopy to identify the type of a suspicious lung lesion detected in other paraclinical tests (X-ray, CT). The endoscopic procedure was accomplished with a direct vision flexible fiber optic bronchoscope (model Karl Storz). In order to measure the local temperature of bronchial epithelium, we applied a thermography catheter (Figure 1), which has been developed in our institute. According to previous experience with a special thermography catheter for the detection of thermal heterogeneity within human atherosclerotic coronary arteries in vivo [4,5] and in urinary bladder [6], we designed a modified thermography catheter, compatible with the bronchoscope. The polyurethane catheter is 4 French (1 French = 0.33 mm) in diameter and has the thermistor probe (Microchip NTC Thermistor, model 100K6 MCD368, BetaTHERM, Ireland), 0.457 mm in diameter attached to its distal part. The gold-plated lead wires of the thermistor pass through the shaft and end in a connector at the distal part of the thermography catheter. The technical characteristics of the polyamide thermistor, according to the manufacturer BetaTHERM Industry, include:

Figure 1.

The steerable thermography catheter. The proximal edge of the catheter with the connector and the distal part of the catheter with the polyamide thermistor (Th)

– temperature accuracy of 0.05°C, measured for whole system,

– a time constant of 300 msec, measured for whole system

– spatial resolution of 0.5 mm, and

– linear correlation of resistance vs. temperature over the range of 33–43°C.

The thermistor leads are connected to a digital multimeter (Protek 506) with an RS232C interface. The multimeter is connected to a personal computer (200 MHz Intel Pentium) and the resistance is displayed on real time. Resistance changes are correlated with temperature changes according to the Steinhart-Hart equation [7]. Finally, after the conversion of resistance values to temperature values the temperature variations are demonstrated on the screen of a personal computer, in which all data are stored.

The catheter was inserted through the biopsy channel of the bronchoscope and its distal part with the attached thermistor was guided to come in touch with the bronchial epithelium. The contact of the thermistor probe was at two sites of any suspicious lesion and also at four sites of the normal epithelium. We also scanned with the thermistor probe an area of 3 to 5 cm beyond the limit of any suspicious area. In each patient approximately 200 temperature measurements were obtained and recorded. Afterwards, we calculated the temperature difference between the sites of the normal tissue, and every suspicious gastric lesion, as the histopathology evaluation confirmed it. This temperature difference is referred as ÄT for every lesion.

Bronchial epithelium biopsies were routinely obtained in every lesion with increased temperature or abnormal endoscopic image. Also, bioptic specimens were collected for histopathological evaluation from the seemingly normal epithelium, where temperature was measured, in order to exclude the existence of carcinoma in situ or inflammation lesion. The evaluation was performed by two separate pathologoanatomists who were unaware of the results of the temperature measurement. Malignant tumors were graded according to the World Health Organization classification [8].

The values of temperature differences presented as mean ± one standard deviation (SD). According to the applied power analysis 12 lesions in each group are needed in order to evaluate temperature differences > 0.5 oC (SD 0.1) at 5% probability level and with statistical power equal to 70%. Due the small number of cases the analysis was based on the calculation of the non-parametric criterion of Mann-Whitney [9]. Simple logistic regression analysis was applied in order to evaluate temperature differences on the probability (i.e. odds ratio, OR) of the detection of malignancy. Finally, cut-off point analysis was used in order to determine the optimal value of the ΔT that differentiate malignant from benign lesions. In particular, the crucial point defined by the largest distance from the diagonal line of the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) (sensitivity × {1 - specificity}) [10]. All reported p-values are from exact two sided tests. STATA release 6 (STATA Corp. College Station, Texas, USA) was used for the statistical calculations.

Results

We studied 20 patients, 14 males (50 – 65 years old) and 6 females (50 – 65 years old) and we measured temperature differences in 22 lesions. None of the patients was under chemotherapeutic or other immunosuppressive medication and all of them had normal body temperature during the bronchoscopic examination. The procedure was brief and uncomplicated for all the patients who had signed an informed consent, according to bio-ethical principles in medical research and the declaration of Helsinki (Revised 1983). Based on the histopathology findings that followed the thermography procedure (see Table 1), 11 lesions were benign showing chronic inflammation and 11 were malignant infiltrated tumors (6 of them had non-small cells lung cancer).

Table 1.

Temperature differences and histopathological characteristics of the investigated lesions

| Malignant tumors | Benign tumors | |||

| ΔT (°C) | Histopathology | ΔT (°C) | Histopathology | |

| Case 1 | 0.80 | NSCLC | 0.3 | Inflammation |

| Case 2 | 0.70 | NSCLC | 1.20 | Inflammation |

| Case 3 | 1.19 | SCLC | 1.70 | Inflammation |

| Case 4 | 0.76 | NSCLC | 0.70 | Inflammation |

| Case 5 | 1.55 | SCLC | 0.09 | Inflammation |

| Case 6 | 1.40 | SCLC | 0.30 | Inflammation |

| Case 7 | 2.10 | SCLC | 0.18 | Inflammation |

| Case 8 | 1.09 | NSCLC | 0.15 | Inflammation |

| Case 9 | 1.50 | NSCLC | 1.40 | Inflammation |

| Case 10 | 1.4 | SCLC | 0.21 | Inflammation |

| Case 11 | 0.80 | NSCLC | 1.60 | Inflammation |

NSCLC = non-small cells lung cancer, SCLC = small cells lung cancer

According to our measurements in benign (chronic inflammation) lesions the mean temperature differences was 0.71 ± 0.6°C, while in malignant tumors ΔT was found 1.23 ± 0.4°C (p < 0.05) (Figure 2). Moreover, ΔT was a significant marker for the discrimination of the type of malignant or benign lesion. In particular, one-Celsius degree difference between normal tissue and suspicious lesion six fold the probability of malignancy (OR = 6.180, 95% CI 0.89 – 42.7). Finally, the cut-off point analysis showed that ΔT greater than 1.05°C constitutes a crucial point that discriminates with accuracy (sensitivity = 64%, specificity = 91%, area under the ROC curve = 0.851, p < 0.001) a malignant from a benign lesion. It seems that the percentage of individuals without malignancy that are correctly classified (specificity) by the suggested procedure is high, while the percentage of individuals with malignancy who are correctly classified (sensitivity) seems smaller.

Figure 2.

Box – Whisker plots showing the median, the interquartile range and the 2.5th – 97.5th percentile of the temperature differences, between the groups of the participants.

Discussion

Here, we measured thermal heterogeneity in malignant and benign bronchial epithelium lesions, in vivo, through a catheter-based technique. The analysis showed that increased temperature is significantly associated with the presence of malignancy. It is worth noting that, changes of temperature between normal tissue and the lesion of interest greater than 1.05-degree, increases the risk of having malignant lesion.

Other investigators have also revealed thermographic findings in the diagnosis of cancer [11-14]. However, submucosae preneoplastic or dysplastic lesions still remain, in some cases, difficult to be diagnosed by the endoscopic examination in clinical practice. Regional hyperthermia of a lesion seems to reflect the degree of angiogenesis and several investigators have featured ultrasound or other methods to prove the increased blood flow [15]. Even more, thermographic findings have been noted in inflammatory cases [16], mostly in complicated forms of the disease or in aggravation of the inflammatory procedure.

In this study we revealed that thermal heterogeneity increases from benign lesions to malignancy, supporting the involvement of temperature rise. Even more, the high specificity of this technique reflects its ability to distinguish a non-malignant bronchial lesion, during conventional bronchoscopy. Furthermore, the use of steerable thermography catheter gives the ability to measure the temperature of lesions that are difficult to detect during conventional endoscopy. Unfortunately, we did not have among the malignant lesions preneoplastic or submucosae cases, so we could not reveal the diagnostic ability of the suggested procedure in these conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, thermographic techniques that can localize the thermal heterogeneity of bronchial epithelium, in vivo, may prove useful in clinical practice, in revealing inflammatory or neoplastic alterations and even in guiding the extraction of biopsy specimens in suspicious high temperature lesions.

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

CS: conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript, CC: participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript, DBP: participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis, EP: participated in the clinical evaluation of the study, VK: participated in the coordination of the study, VP: participated in the coordination of the study, and PKT: participated in the coordination of the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Christodoulos Stefanadis, Email: cstefan@cc.uoa.gr.

Christina Chrysohoou, Email: chrysohoou@usa.net.

Demosthenes B Panagiotakos, Email: d.b.panagiotakos@usa.net.

Elisabeth Passalidou, Email: chrysohoou@usa.net.

Vasiliki Katsi, Email: chrysohoou@usa.net.

Vlassios Polychronopoulos, Email: chrysohoou@usa.net.

Pavlos K Toutouzas, Email: chrysohoou@usa.net.

References

- Henderson BE, Ross RK, Pike MC. Towards the primary prevention of cancer. Science. 1991;254:1131–1134. doi: 10.1126/science.1957166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husband J. Diagnostic techniques: their strengths and weaknesses. Br J Cancer. 1980;41:21–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Nagata K, Akagi K, Nasu R, Imamura M, Kimura H, Tanaka Y. New technique for mediastinal temperature measurement in hyperthermic cancer treatment: balloon catheter in the azygos vein. J Int Med Res. 1998;26:50–56. doi: 10.1177/030006059802600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanadis C, Toutouzas P. In vivo local thermography of coronary artery atherosclerotic plaques in humans. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1079–1080. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanadis C, Diamantopoulos L, Vlachopoulos C, Tsiamis E, Dernellis J, Toutouzas K, Stefanadi E, Toutouzas P. Thermal heterogeneity within human atherosclerotic coronary arteries detected in vivo: A new method of detection by application of a special thermography catheter. Circulation. 1999;99:1965–1971. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.15.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanadis C, Chrysochoou C, Markou D, Petraki K, Panagiotakos DB, Fasoulakis C, Kyriakidis A, Papadimitriou C, Toutouzas PK. Increased temperature of malignant urinary bladder tumors, in vivo; the application of a new method based on a catheter technique. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:686–671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston Sears F, Zemansky M. College Physics. London, Addison Wesley Publishing Company. 1966.

- World Health Organization Histological Typing of lung Tumors. International Classification of Tumors. Geneva. 1977.

- Gibbons JD. Nonparametric Statistical Inference. New York, Marcel Dekker, Inc. 1985. pp. 141–149.

- Guangqin MA, Hall WJ. Confidence bands for receiver operating characteristic curve. Med Decis Making. 1993;13:191–197. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head JF, Elliott RL. Thermography. Its relation to pathologic characteristics, vascularity, proliferation rate, and survival of patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Cancer. 1999;79:186–188. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970101)79:1<186::AID-CNCR28>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn C, Beldermann F, Frey H, Reinhardt S, Sohn J, Bastert G. Diagnosis of blood flow in breast tumors with increased blood pressure. New possibility in tumor field diagnosis. Radiology. 1997;37:643–650. doi: 10.1007/s001170050266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isard HJ. Thermography in breast cancer. JAMA. 1992;268:3074. doi: 10.1001/jama.268.21.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautherie M. Thermopathology of breast cancer. Measurment and analysis of in vivo temperature and blood flow. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1980;335:383–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb50764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edell SI, Eisen MD. Current imaging modalities for the diagnosis of breast cancer. Del Med. 1999;71:377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson N, Balsitis M, Everitt S, Hawkey CJ. Angiogenesis in gastric ulcers: impaired in patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gut. 1995;37:191–194. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]