Abstract

In this article, we characterize the fluorescence of an environmentally sensitive probe for lipid membranes, di-4-ANEPPDHQ. In large unilamellar lipid vesicles (LUVs), its emission spectrum shifts up to 30 nm to the blue with increasing cholesterol concentration. Independently, it displays a comparable blue shift in liquid-ordered relative to liquid-disordered phases. The cumulative effect is a 60-nm difference in emission spectra for cholesterol containing LUVs in the liquid-ordered state versus cholesterol-free LUVs in the liquid-disordered phase. Given these optical properties, we use di-4-ANEPPDHQ to image the phase separation in giant unilamellar vesicles with both linear and nonlinear optical microscopy. The dye shows green and red fluorescence in liquid-ordered and -disordered domains, respectively. We propose that this reflects the relative rigidity of the molecular packing around the dye molecules in the two phases. We also observe a sevenfold stronger second harmonic generation signal in the liquid-disordered domains, consistent with a higher concentration of the dye resulting from preferential partitioning into the disordered phase. The efficacy of the dye for reporting lipid domains in cell membranes is demonstrated in polarized migrating neutrophils.

INTRODUCTION

Membranes with lipids of different melting temperatures may exhibit phase separation, forming coexisting domains. With cholesterol in the membrane, the domains may be in liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered phases (1). This phenomenon has gained broad interest in the last decade, since phase separation is thought to organize molecules in cell plasma membranes and plays an important role in cell function (2). The liquid-ordered phase domains in plasma membranes are defined as rafts. With cold, nonionic detergent extraction methods, rafts have been isolated from plasma membranes as a detergent-resistant fraction that is enriched in glycosphingolipids, cholesterol, and specific membrane proteins (3).

Biophysical studies on lipid phases are most readily performed on model membranes instead of cells. This is because chemical components and physical conditions are under total experimental control in model membranes. The domains of model membranes can be at the micrometer scale, allowing them to be resolved by light microscopy. Phase separation has been studied under the microscope using fluorescent probes. Most probes partition preferentially into one phase: for instance, lissamine rhodamine 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine and perylene segregate preferentially into the liquid-disordered and liquid-ordered phases, respectively (4). Laurdan uses a different mechanism to differentiate the two phases. It exhibits an emission spectrum shift of up to 50 nm and a photoselection effect in the domains of different phases (5,6). Thus, laurdan labels both phases but displays distinct optical properties in each. Laurdan is excited with near-ultraviolet light, making it advantageous to use two-photon fluorescence (TPF) microscopy. This has the added advantage in cellular applications (7) of minimizing bleaching and the damaging effects of ultraviolet excitation, as only the dye molecules in the optical section are excited.

However, imaging of rafts in live cells has not been widely reported and can be quite challenging. Most of the probes used in model membranes are mixed with lipids before vesicle development, so the loading method cannot be readily applied to live cells. Cell biologists often turn to fluorescently labeled toxins and antibodies, which bind to lipids or proteins in rafts; these include cholera toxin subunit B for GM1 and antibodies against caveolins (8,9). Fluorescent-protein-tagged constructs of proteins known to associate with rafts have also permitted the visualization of domains in live cells (10). These probes indicate the location of a certain chemical component, but not the physical phase of the domains, which defines rafts; of course, specific labels and antibodies can also be problematic for live-cell imaging experiments. Furthermore, analysis of the diffusion rate of molecules in plasma membranes suggests that the size of rafts may be at the nanometer scale, which is not resolvable by light microscopy (11). For example, electron microscopy reveals caveolae, raft-like structures, with a size of 25–150 nm in diameter (12). An additional consideration is that, according to biochemical analysis, rafts are thought to be heterogeneous in both lipid and protein components (13), so labeling a particular chemical component may not visualize the general distribution of rafts. Indeed, biophysical studies on model membrane domains and cell biological studies on cell membrane heterogeneity suffer from a dearth of common tools. Therefore, information derived from model membrane studies is not readily connected to cell membrane physiology.

Di-4-ANEPPDHQ is a potentiometric styryl dye that has recently been introduced for studies of neuronal activity (14). It is reasonably water-soluble yet has a high avidity for membrane. Thus, a simple solution of the dye in extracellular medium readily stains live cells. It inserts into one leaflet of the bilayer membrane, with its chromophore aligned by the surrounding lipid molecules. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ is conveniently excited by blue light, including the common 488-nm laser line available in all confocal microscopes. As with other styryl dyes (15), it has a high-fluorescence quantum efficiency and large Stokes shift when bound to membranes, but very little fluorescence in water. This minimizes background fluorescence contributions. Its spectra are solvatochromic and electrochromic, with the latter effect providing the basis for its sensitivity to membrane potential.

In this article, we explore environmental influences on the optical properties of di-4-ANEPPDHQ that promise to make it an excellent probe of membrane domains. We find that the local cholesterol concentration and lipid phase affect the dye's emission spectrum. Given these optical properties, di-4-ANEPPDHQ successfully differentiates liquid-ordered and -disordered phases in giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) with both single photon fluorescence (SPF) and TPF. The dye also has a much higher second harmonic generation (SHG) signal in the liquid-disordered phase. A preliminary account of this work has appeared as a Biophysical Letter (16). Here we provide data that helps explain the physical origin of these optical phenomena and further apply the method to a variety of model membrane systems.

We also successfully demonstrate the applicability of di-4-ANEPPDHQ in a live cell system, polarized neutrophils, which have lipid rafts concentrated at the front lamellipodia (7). The dye shows a smaller red/green fluorescence ratio in the front lamellipodia compared to those of the rest of the cell. The ratio difference between the front and rear disappears after cholesterol depletion, which breaks up rafts. We anticipate that the dye will reveal membrane heterogeneity in other cells and become a unifying tool for both model-membrane and live-cell investigations of lipid domains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The lipids 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), cholesterol, egg phosphatidylcholine, and brain sphingomyelin, were all obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). The dye, di-4-ANEPPDHQ, was synthesized in our laboratory according to the published procedure (14).

Vesicle development

Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs)

A solution of 5 mg lipids in 0.2 ml chloroform was prepared with the desired molar ratio of lipids. The solutions were dried under argon, and held in a vacuum chamber for 1 h to completely evaporate the solvent. Distilled deionized water (2 ml) was added to hydrate the lipids for 1 h. The lipid suspension is pushed through a polycarbonate membrane with 3-μm pores in a miniextruder system (Avanti Polar Lipids) 21 times. If there is DPPC in the lipid mix, the hydration and extrusion are done at 60°C to keep the lipid in liquid phase during the procedure.

GUVs

Twenty microliters of 1 mg/ml lipid solution in chloroform was spread evenly on two indium-tin-oxide-coated glass slides (Delta Technologies, Stillwater, MN). The chloroform was evaporated under argon and held in a vacuum chamber for 1 h. The two slides were separated by 0.39-mm-thick Teflon spacers with the lipid layers facing each other, forming a capacitor sandwich. The space between the slides was filled with Millipore water and connected to a function generator (10 MHz, Wavetek, San Diego, CA), producing a 10-Hz sinusoidal wave of 3 V for 1 h. The GUVs were developed at 60°C if there was DPPC or brain sphingomyelin in the lipid mixture (17,18).

Cell preparation

Neutrophil isolation

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes from mouse bone marrow were isolated from femurs as described (19), with some modifications. Marrow cells were flushed from the bones using Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) without Ca2+/Mg2+ (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) + 0.1% BSA + 5 mM Hepes (GIBCO). Red blood cells were lysed with 0.15 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2 EDTA for 4 min at room temperature. The remaining leukocytes were washed twice in HBSS (Ca2+/Mg2+-free) + 0.1% BSA + 5 mM Hepes and resuspended in 3 ml of a 45% Percoll solution in HBSS (Ca2+/Mg2+-free). The leukocytes were loaded on a Percoll density gradient, which had a Percoll concentration of 81%, 62%, 55%, and 50% from the bottom to the top. Cells were centrifuged at 1600 g for 30 min at room temperature. The neutrophil band between the 81% and 62% layers was harvested, and washed twice in fresh HBSS (Ca2+/Mg2+-free) + 0.1% BSA + 5 mM Hepes.

Polarization

The cells were plated in coverglass-bottom dishes and incubated for 5 min. The chemoattractant ligand fMLP (10 μM) was added and after 10 min incubation the polarized neutrophils were ready for imaging.

Cholesterol depletion

Plated cells were incubated in buffer solution with 10 mM methylated β-cyclodextrin (Cycoldextrin Technologies Development, High Springs, FL) for 15 min at 37°C. After the cylcodextrin solution was washed away, cells were polarized with ligand.

Staining

LUVs were stained with 2 and 1 μM di-4-ANEPPDHQ added into cuvettes in spectrum-shift and affinity studies, respectively. GUVs were stained by 10 μM di-4-ANEPPDHQ. Neutrophils were treated with 3 μM di-4-ANEPPDHQ in buffer solution and immediately transferred to the microscope for imaging.

Spectrum measurement

LUVs

In a cuvette, 1 ml of the LUV suspension from the extruder is diluted by water to 3 ml and stained with 2 μM di-4-ANEPPDHQ. The spectra were measured by a Fluorolog spectrofluorometer (SPEX, Hoboken, NJ). The sample temperature was controlled by an MGU Lauda circulation bath (Brinkmann, Westbury, NY). For emission spectra measurement, 475 nm excitation was used, and for excitation spectra measurement, 630 nm emission was used. All spectra were corrected for the wavelength dependence of the monochromators, and, for emission spectra, for the detector sensitivity at different wavelengths.

Affinity analysis

LUV suspensions of 0, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.08, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mg/ml were each equilibrated with 1 μM di-4-ANEPPDHQ, and emission spectra were recorded. The signal intensity at the peak wavelength was used in a one-site saturable binding analysis.

Imaging

For confocal SPF imaging of GUVs, we used a Zeiss Meta multiwavelength confocal microscope system mounted on an Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). The di-4-ANEPPDHQ fluorescence is excited by the 488-nm line of an argon ion laser, collected by a plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil DIC objective, and filtered through emission channels of either BP 650–710 nm or BP 500–550 nm. The lambda function of the Meta system was used to collect emission spectra from 521 to 703 nm.

The neutrophils images are taken with an LSM 510 confocal microscope mounted on a Zeiss Alexiovert. The samples are excited by a 488-nm argon ion laser line. The fluorescence emission is collected by a plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil DIC objective and filtered through either LP 650-nm or BP 505–550 nm emission channels. Ratio images are calculated by dividing the emission intensity from the LP650 channel by the emission intensity from the BP 505–550 channel on a pixel by pixel basis. In a separate set of experiments, we used the Meta system to acquire spectra from the front and rear of polarized neutrophils as described above for the GUVs.

The excitation for both TPF and SHG, femtosecond laser pulses at 910 nm, is from a Mira 900 Ti:sapphire ultrafast laser (Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) pumped by a 10 W Verdi doubled solid-state laser (Coherent). The laser is circularly polarized by a half-waveplate (CVI Laser) and a quarter-waveplate (CVI Laser). A Fluoview scanning confocal imaging system (Olympus America, Melville, NY) directs the scanning beam into the sample through an IR-Achroplan 40×/0.8NA water-immersion objective on an Axioskop microscope (Zeiss). TPF is collected backward through the objective and a bandpass filter (either 540/50 or 675/50 nm), and detected by a photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu, Tokyo, Japan). The SHG is collected forward through a 0.9 NA condenser and a 455-nm filter onto a photon-counting head (Hamamatsu). Both TPF and SHG signals are input to the Fluoview amplifier board (Olympus America) (20).

RESULTS

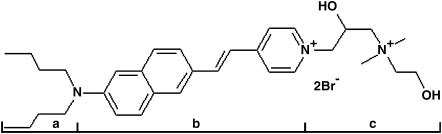

Di-4-ANEPPDHQ is a relatively new member of the series of styryl dyes developed in our laboratory as fluorescent sensors of transmembrane potential (21). Compared with widely used ANEPPS dyes that are zwitterionic, di-4-ANEPPDHQ has two positive charges on its headgroup (Fig. 1), which give it two unique properties. First, it is water soluble without the need of detergents or cyclodextrin as vehicles. Second, its double positive charge retards the rate of flipping from the outer leaflet of the bilayer to the inner leaflet. This will also decrease the rate of internalization of the dye, which can produce significant background fluorescence in cell studies. These two properties make di-4-ANEPPDHQ a better membrane probe than the ANEPPS dyes while retaining the general styryl attributes of low aqueous fluorescence, high membrane fluorescence, and large Stokes shift.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of di-4-ANEPPDHQ: (a) two hydrocarbon chains to facilitate dye binding to the lipid membranes; (b) the chromophore; and (c) the headgroup, with two positive charges.

Liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered membrane domains differ in both chemical composition and physical phases. In the liquid-ordered phase, the membrane is enriched with cholesterol and lipids with a high melting temperature. The ordered molecules are more tightly packed, with less flexibility and slower diffusion. In the liquid-disordered phase, the membrane is enriched with lipids with a low melting temperature. The disordered molecules are loosely packed, with more flexibility and faster diffusion. These environmental differences in the two domains could influence di-4-ANEPPDHQ's fluorescence. We separately investigated how the dye's spectrum responds to these chemical and physical factors.

We developed LUVs with different lipid components and used temperature to control their phase transitions. We stained these vesicles with di-4-ANEPPDHQ and measured the dye's excitation and emission spectra with a spectrofluorometer. The basic components of the vesicles are DOPC, DPPC, and cholesterol. DOPC and DPPC have the same headgroup and differ in the length and saturation of fatty acid chains. DOPC is an unsaturated lipid with a transition temperature of −21°C, whereas DPPC is a saturated lipid with a transition temperature of 41°C (22).

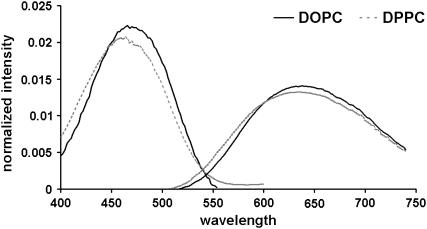

To test the chemical components' influence, we first measured the dye's spectra in LUVs of pure DOPC and pure DPPC at 60°C (Fig. 2). At this temperature, the vesicles of each lipid are in the liquid-disordered phase. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ's excitation and emission spectra in DPPC LUVs are slightly blue-shifted relative to its spectra in DOPC LUVs. Therefore, we conclude that di-4-ANEPPDHQ is not particularly sensitive to the environmental difference caused by the unsaturation of the fatty acid chains of the phosphatidylcholines. In other words, the dye will not readily distinguish the liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered phase domains based on a concentration difference in these saturated and unsaturated lipids alone.

FIGURE 2.

Excitation and emission spectra of di-4-ANEPPDHQ in pure DOPC and pure DPPC LUVs at 60°C: solid, DOPC; dotted, DPPC.

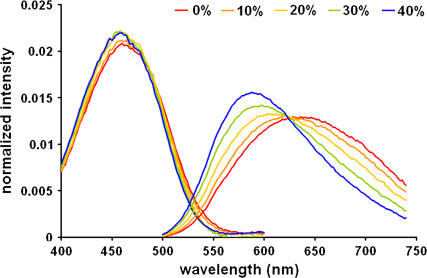

Another chemical difference between the liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered phases can be cholesterol concentration. So we prepared LUVs of DPPC with different cholesterol concentrations from 0 to 40 mol %, and measured di-4-ANEPPDHQ's spectra in them at 60°C. At this temperature LUVs of all these mixtures will be in the liquid-disordered phase (23), so the only difference between these vesicles is the cholesterol concentration. In Fig. 3, the excitation spectrum blue-shifts a little with increasing cholesterol concentration, whereas the emission spectrum shows significant changes. Increasing the cholesterol concentration from 0 to 40 mol % shifts the peak of the emission spectrum from 628 nm to 588 nm. Another obvious change is that the emission spectrum is getting narrower: the half-peak width changes from 169 nm to 122 nm. We also examined the effect of varying cholesterol concentrations in DOPC LUVs at room temperature. The spectra showed similar changes with increasing cholesterol concentration (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that di-4-ANEPPDHQ's fluorescence emission is sensitive to the cholesterol concentration.

FIGURE 3.

Excitation and emission spectra of di-4-ANEPPDHQ in DPPC LUVs with different cholesterol concentration at 60°C. Cholesterol concentration: 40% (blue), 30% (green), 20% (yellow), 10% (orange), and 0% (red).

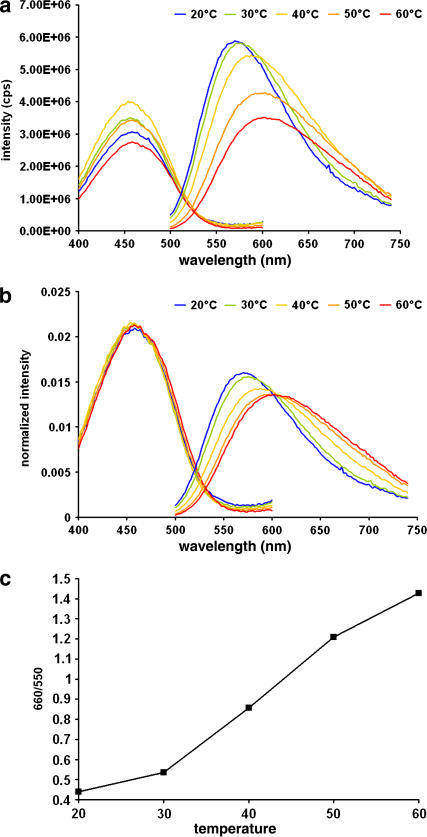

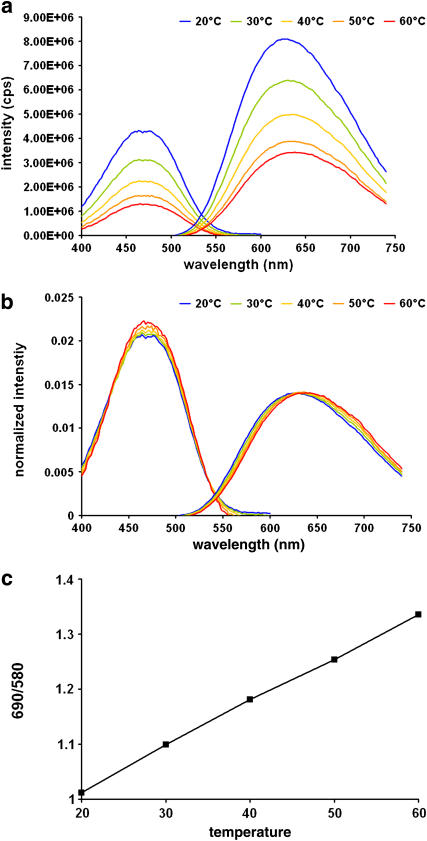

We next considered the direct effect of the physical phase on the spectra. We developed LUVs with DPPC and cholesterol at a molar ratio of 7:3. Membranes with this composition will be in a liquid-disordered phase at 60°C and in a liquid-ordered phase at 20°C (23). We changed the temperature to control the phase transition, and measured di-4-ANEPPDHQ's spectra. Fig. 4 a shows the excitation and emission spectra at different temperatures. From the emission spectra, we can see that the fluorescence intensity decreases with the temperature increase. To observe the spectrum shift more clearly, we normalized all the spectra by the area under the curves (Fig. 4 b). The excitation spectrum does not change, whereas the emission spectrum blue-shifts with the temperature decrease. The emission peak wavelengths at 60°C and 20°C are around 602 nm and 570 nm, respectively. The emission spectrum also gets narrower with the temperature decrease. The half-peak width changes from 152 nm at 60°C to 114 nm at 20°C.

FIGURE 4.

Excitation and emission spectra of di-4-ANEPPDHQ in LUVs composed of of 70% DPPC and 30% cholesterol at 60°C (red), 50°C (orange), 40°C (yellow), 30°C (green), and 20°C (blue). (a) Excitation and emission spectra. (b) Normalized excitation and emission spectra. (c) A plot of the ratio of intensities at 650 nm to those at 550 nm reveals that the emission spectrum shift is steepest around 40°C.

To assess the relationship between the emission spectrum and the temperature, we divide the emission intensity at 660 nm by that at 550 nm, and plot the ratio against the corresponding temperatures (Fig. 4 c). The emission changes most rapidly around 40°C, which is close to the transition temperature of DPPC, 41°C. Multilamellar vesicles of the DPPC and cholesterol binary mixtures have been studied by nuclear magnetic resonance and differential scanning calorimetry (23). The phase diagram derived from these studies shows that small-scale (r < 1 μm) liquid-ordered phase domains will appear within the liquid-disordered phase domains when the temperature is decreased to close to the transition temperature. With further temperature decrease, the membrane will eventually become homogeneous in the liquid-ordered phase. Therefore, we suspect that the rapid emission shift in Fig. 4 b mainly reflects the phase transition and is not some other effect of the temperature change.

To test the effect of temperature in the absence of a phase transition, we measured the temperature dependence with LUVs composed of pure DOPC as a control. DOPC has a transition temperature of −21°C, so in this control experiment, changing temperature from 20°C to 60°C does not cause a phase transition. In Fig. 5 a, we observed a fluorescence intensity decrease with temperature increase, as in Fig. 4 a. In Fig. 5 b, the spectra are normalized, showing no shift in the excitation spectrum, and a very small and continuous emission-spectrum blue shift from 638 nm to 630 nm as temperature decreases from 60°C to 20°C. The rate of emission change is analyzed by plotting the emission ratios at 690:580 nm against the temperatures (Fig. 5 c), revealing a linear relationship within this temperature range. Additionally, the emission spectrum (Fig. 5 b) does not show any signifcant narrowing as a function of temperature. Comparing Figs. 4 and 5, we can draw the following conclusions: 1), di-4-ANEPPDHQ's fluorescence intensity decreases as the temperature increases; and 2), the dye's emission spectrum blue-shifts and narrows during the membrane phase transition from the liquid-disordered to the liquid-ordered phase.

FIGURE 5.

Spectra of di-4-ANEPPDHQ in LUVs of pure DOPC at 60°C (red), 50°C (orange), 40°C (yellow), 30°C (green), and 20°C (blue). (a) Excitation and emission spectra. (b) Normalized excitation and emission spectra. (c) A plot of the ratio of emission intensities at 690 nm to those at 580 nm reveals that the small spectrum shift is linear with the temperature.

In summary, we have shown that the di-4-ANEPPDHQ fluorescence is not sensitive to the fatty acid chain difference between DOPC and DPPC. Its emission spectrum reports the cholesterol concentration increase by blue-shifting and narrowing. Its emission spectrum also shifts and narrows in response to the transition between the liquid-disordered and liquid-ordered phases. Additionally, its fluorescence intensity decreases with temperature increase. For the extreme case of liquid-disordered DOPC versus liquid-ordered 7:3 DPPC/cholesterol membranes, the difference in emission wavelength maximum is 60 nm. Because of this large emission spectrum difference, di-4-ANEPPDHQ should differentiate liquid-ordered and -disordered domains coexisting in membranes.

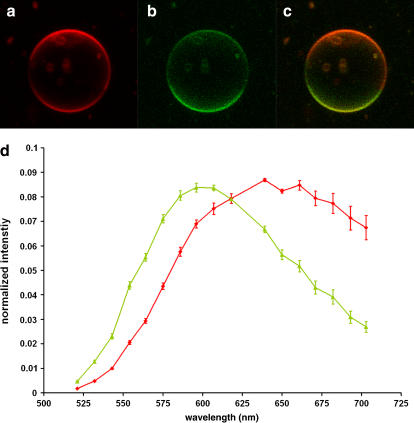

To test this idea, we used di-4-ANEPPDHQ to stain GUVs with DOPC, DPPC, and cholesterol in a mixture of 2:2:1 molar ratio. At room temperature, membranes with this composition form separate liquid-ordered and -disordered phases (18). DOPC is more concentrated in the disordered phase, whereas DPPC and cholesterol are more concentrated in the ordered phase. In Fig. 6, a–c, di-4-ANEPPDHQ shows opposite contrast patterns for the green (500–550 nm) and red (650–710 nm) emission band channels, reflecting domain phase separation within the GUV. Based on our analysis of the LUV data of Figs. 2–5, we assign the greener domains in the GUV images to the liquid-ordered, cholesterol-enriched phase and the redder domains to the liquid-disordered, cholesterol-depleted phase. To confirm this, we have shown that perylene, a probe known to partition preferentially into the liquid-ordered phase (4), colocalizes with the greener di-4-ANEPPDHQ emission. Using the spectral recording capabilities of the multielement detector in the Zeiss Meta confocal microscope, we were able to obtain emission spectra from these two regions. Fig. 6 d shows the normalized emission spectra of di-4-ANEPPDHQ in the liquid-ordered (greener) and liquid-disordered (redder) domains of GUVs with this composition. The emission peak in the green domain is ∼575 nm, whereas in the red domain it is ∼607 nm. From Fig. 6 d, we can also see that the green emission spectrum is narrower than the red one, as predicted. This is not as large as the 60-nm spectral difference displayed between the LUVs composed of pure DOPC versus DPPC/cholesterol; the smaller spectral difference between the domains in the GUVs presumably reflects the incomplete segregation of lipids into the two domains (see Discussion). From these averaged normalized emission spectra, we can assess the relative contrast between the two domains within the wavelength ranges corresponding to the emission filters used for Fig. 6, a–c; the intensity ratio for liquid-ordered/liquid-disordered is 3.7 within the 500–550 nm green band, whereas it is 0.23 for the 650–710 nm channel. This explains why the choice of filters in Fig. 6, a–c, permits ready visualization of the separated phases.

FIGURE 6.

Confocal fluorescent images of a GUV (2:2:1 DPPC/DOPC/cholesterol) stained by di-4-ANEPPDHQ. (a) BP 650–710 nm emission channel. (b) BP 500–550 nm emission channel. (c) Merging of a and b images. (d) Emission spectra of the two domains. Excitation is at 488 nm for all images.

Di-4-ANEPPDHQ senses cholesterol concentration and phase difference, hallmarks for liquid-ordered and -disordered phase domains, implying that the dye would distinguish domains in GUVs composed of more natural lipid mixtures. To test this hypothesis, we made GUVs with extracted natural lipids: egg phosphatidylcholine, brain sphingomyelin, and cholesterol in a 2:2:1 molar ratio. GUVs of this mixture can have coexisting liquid-ordered and -disordered phase domains at room temperature (18). Egg phosphatidylcholine is a mixture of L-α-phosphatidylcholines with various fatty acid chains, and its main component is 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, an unsymmetric phospholipid with a low transition temperature of −2°C (22). Brain sphingomyelin is a mixture of different ceramide-1-phosphocholines, and its main component is stearoyl sphingomyelin, with a high transition temperature of 41.5°C (24). 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and stearoyl sphingomyelin are common cell plasma membrane components, so this test can provide a first indication of whether di-4-ANEPPDHQ might be suited for cell biological applications. The two lipids differ not only in their fatty acid chains, which determine the transition temperature, but also in their backbone structures. Therefore they indicate whether the dye's sensitivity will be affected by factors other than the fatty acid chains. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ again displayed emission spectral differences between the two coexisting phases that permitted visualization of domains in images of these GUVs. (Fig. 7). The images in Fig. 7 were acquired using the same emission wavelengths as the images in Fig. 6. The spectrum peak in the ordered phase is around 596 nm, whereas in the disordered phase it is ∼639 nm (Fig. 7 d). Thus, both spectra are red-shifted compared to the simpler mixture of synthetic lipids analyzed in Fig. 6; this may reflect an overall greater disorder in both domains of the natural lipid GUVs. The spectrum in the disordered domains is also broader than in the ordered domains. Analysis of the relative contrast in the two domains shows that the intensity ratio for liquid-ordered/liquid-disordered is 2.3 within the 500–550 nm green band, whereas it is 0.53 for the 650–710 nm channel. These contrast ratios are substantial, but not as great as those found for the synthetic lipids; this accounts for the poorer contrast in Fig. 7, a–c, compared to Fig. 6, a–c. This experiment shows that the dye also distinguishes domains with natural lipids with various backbone structures and complex mixtures of fatty acids.

FIGURE 7.

Confocal fluorescent images of a GUV composed of natural lipids (2:2:1 brain sphingomyelin/egg phosphatidylcholine/cholesterol) stained with di-4-ANEPPDHQ. (a) BP 650–710 nm emission channel. (b) BP 500–550 nm emission channel. (c) Merging of a and b images. (d) Emission spectra of the two domains.

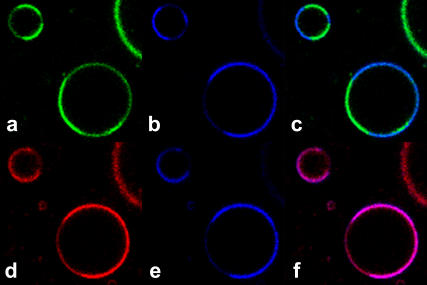

In all the experiments above, we imaged di-4-ANEPPDHQ's SPF. In lipid membranes, the dye can also be imaged by two nonlinear optical methods, TPF and SHG. Therefore, we also imaged GUVs (2:2:1 DOPC/DPPC/cholesterol) with these two methods (Fig. 8). The mechanisms of TPF and SPF are different in excitation but the same in emission. Since the dye's sensitivity to the domains relies on its emission-spectrum shift, the TPF and SPF results should be similar. As expected, in TPF images one domain shows greater red emission, whereas the other shows greater green emission. The SHG signal is stronger in the domains with greater red TPF, indicating that the dye has a higher SHG signal in the liquid-disordered phase than in the liquid-ordered phase.

FIGURE 8.

TPF (red and green) and SHG (blue) images of GUVs (2:2:1 DOPC/DPPC/cholesterol) stained with di-4-ANEPPDHQ. (a) TPF from the 515–565 nm emission channel. (b) SHG signal (transmitted light at 455 nm) taken simultaneously with a. (c) Merging of images in a and b. (d) TPF from the 650–700 nm emission channel. (e) SHG signal taken simultaneously with d. (f) Merge of images in d and e. Note that because of the need for a filter change, the upper and lower rows of images were not acquired simultaneously. The incident light was at 910 nm.

SHG is a coherent scattering effect from noncentrosymmetrically arrayed hyperpolarizable molecules (25–27). The styryl chromophore of di-4-ANEPPDHQ displays strong resonance-enhanced hyperpolarizability, and in membranes the dye is aligned by the surrounding lipids, with the molecules arranged in the same orientation in a single leaflet. Therefore, membrane-bound di-4-ANEPPDHQ generates second harmonics. The signal intensity of SHG is quadratic with respect to the dye's concentration, so one hypothesis for the higher SHG signal in the liquid-disordered phase is that the dye preferentially partitions into the liquid-disordered phase over the liquid-ordered phase. A significant, but lower, concentration of dye in the liquid-ordered phase could produce sufficient fluorescence emission to account for the comparable intensities from both phases, if the fluorescence quantum efficiency of the dye were higher in liquid-ordered than in liquid-disordered phases.

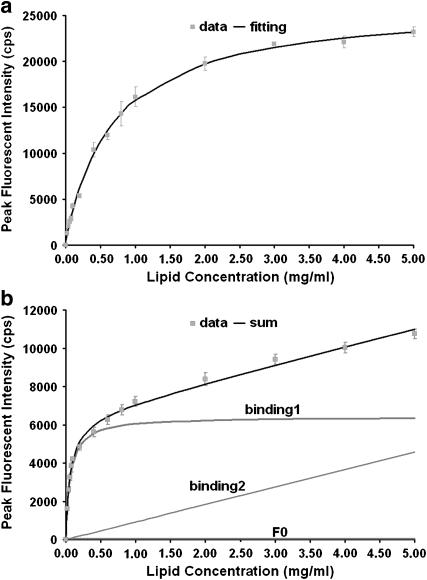

To estimate di-4-ANEPPDHQ's relative affinity to membranes in liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered phases, we titrated 1 μM of dye with LUVs at concentrations from 0 to 5 mg/ml and measured the fluorescence enhancement associated with dye binding. The fluorescence at wavelengths corresponding to maximal excitation and emission of the bound form is plotted against the lipid concentration of the LUV suspensions (Fig. 9). We then fit the data to a one-site saturable binding model via nonlinear least-squares analysis (15):

|

(1) |

Fc is the fluorescence when the lipid concentration is C; F∞ is the fluorescence when all of the dye is bound; F0 is the almost negligible fluorescence from aqueous dye in the absence of lipid; Kd is the parameter for the relative affinity of the dye to the LUV, measured in mg/ml. We made LUVs of pure DOPC and 2:1 DPPC/cholesterol, and measured their emission spectra at room temperature, at which LUVs of the two mixtures would be in disordered and ordered phases, respectively. Excited with 475 nm, the peak emission in DOPC LUVs is 620 nm, whereas in DPPC/cholesterol LUVs it is 568 nm. The ordered-phase data fits the one-site saturable binding model (Fig. 10 a), in which F0 = 407, F∞ = 2.6 × 104, and Kd = 0.691 mg/ml. The disordered-phase data does not fit a one-site saturable binding model; it can be fit with a sum of high- and low-affinity binding isotherms:

|

(2) |

FIGURE 9.

Peak fluorescence intensity changes in LUV suspension titrations: (a) LUVs with 2:1 DPPC/cholesterol; (b) LUVs with DOPC. The solid curves correspond to the binding isotherm fits described in the text.

FIGURE 10.

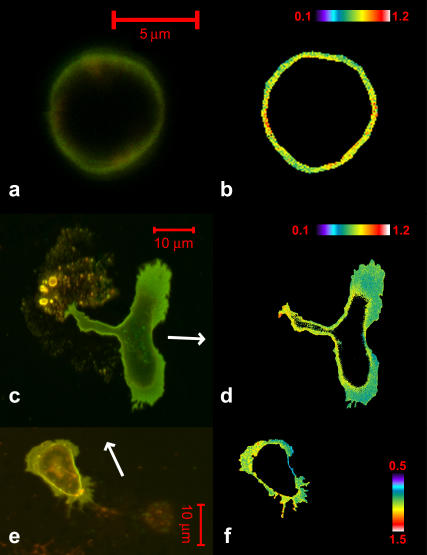

Confocal images of di-4-ANEPPDHQ fluorescence in neutrophils. The left column displays an overlay of red (LP650) and green (BP 505–550) emission channels, and the right column shows the red/green ratio. (a and b) A nonpolarized neutrophil. Scale bar, 5 μm; pseudocolor bar of ratio value 0.1–1.2. (c and d) A polarized neutrophil. Scale bar, 10 μm; pseudocolor bar of ratio value 0.1–1.2. (e and f) A cholesterol-depleted neutrophil. Scale bar, 10 μm; pseudocolor bar of ratio value 0.5–1.5. In c and e, the direction of migration is indicated by arrows.

In Fig. 10 b, the fitting curve for the measured data is the sum of the fluorescence from free dye, bound dyes in form 1, and bound dyes in form 2. We find that F0 = 53, F∞1 = 6488, Kd1 = 0.063 mg/ml, F∞2 = 3.1 × 106, and Kd2 = 3.4 × 104 mg/ml. The first binding form has high affinity, whereas the second binding form has very low affinity. Because the Kd2 value of 3.4 × 104 is much higher than the lipid concentrations used here, the second binding form shows an essentially linear fluorescent increase with increasing lipid concentration in this range. From Fig. 10 b, when the lipid concentration is low, binding form 1 is the main contributor to the fluorescence. In the GUV experiments, the lipid concentration in the preparation is ∼0.1 mg/ml, which is in the low concentration range of the titration curve, so the high-affinity binding site is the major binding form at this lipid concentration and contributes ∼98% of the fluorescence in the disordered phase domain. Therefore, the dye's relative affinities to the disordered phase and ordered phase are estimated by comparing Kd1 = 0.063 mg/ml and Kd = 0.691 mg/ml, respectively. Thus, the dye's concentration should be ∼10 times higher in the disordered phase than in the ordered phase, explaining the higher SHG signal in the disordered phase.

After this series of studies on di-4-ANEPPDHQ in model membranes, we tested the efficacy of the dye to image lipid domains in cells. Because individual rafts are smaller than the spatial resolution of the light microscope (11), we chose polarized neutrophils, which are thought to have a high density of rafts in their front lamellipodia, with the expectation that the dye could show shorter emission wavelength in the region of high raft localization.

Neutrophils can be activated by a chemoattractant fMLP (formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine). This is an important step for the recruitment of leukocytes during the inflammatory response. After activation, neutrophils are polarized with a blunted leading edge and a narrower posterior. F-actin in the lamellipodia in the front drives the cell to migrate toward the direction of higher chemoattractant gradient. This morphology change and motility is mediated by the polarized distribution of proteins and lipids, such as F-actin and PIP3 (28). Membrane reorganization during polarization recruits rafts to the front lamellipodia. Immunofluorescent staining of raft markers, sphingolipid GM3 and calcium channel TRPC-1, indicates that after polarization rafts are concentrated toward the leading edge of neutrophils. Cholesterol depletion disrupts rafts and abolishes the reorganization of the two markers during the polarization (29,30). Raft distribution in the neutrophils is also supported by emission spectrophotometry studies of cells stained by laurdan. Laurdan's spectrum blue-shifts in the liquid-ordered phase. Its emission spectrum from the front lamellipodia blue-shifts compared with the cell body and nonpolarized cell. The difference disappeared after cholesterol depletion (30). Therefore, we regard polarized neutrophils as a well studied cell system to test di-4-ANEPPDHQ.

To visualize lipid-domain heterogeneity with our probe, we divided images with emission at >650 nm by images acquired simultaneously through a 505–550 nm emission bandpass filter. Since the liquid-disordered phase has a dye emission spectrum that is shifted to the red compared to the dye in the liquid-ordered phase, a ratio of red/green emission intensities provides an indication of the relative population of domains at each point in the membrane. Similarly, the dye responds to high cholesterol by shifting its emission spectrum to the green, so the emission ratio for red/green wavelength bands will be sensitive to cholesterol concentration. We calculated this ratio for each pixel and can display and analyze the pattern of ratio values in the resulting image. Since rafts are presumed to be composed of high cholesterol in a liquid-ordered phase, pixels with low red/green ratios will correspond to patches of membranes with a higher density of rafts than pixels with high red/green ratios. The nonpolarized neutrophils are approximately spherical (Fig. 10, a and b). Di-4-ANEPPDHQ does not show significant ratio heterogeneity along the membranes in these cells. In polarized neutrophils (Fig. 10, c and d), di-4-ANEPPDHQ has a smaller ratio value in the lamellipodia at the leading edge. After cholesterol depletion, the neutrophils still can be polarized by fMLP, but the ratio difference of di-4-ANEPPDHQ between the front and back (Fig. 10, e and f) is largely abolished.

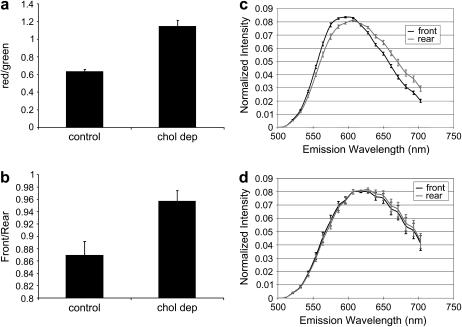

Fig. 11 is a statistical summary of several such experiments on polarized neutrophils with and without cholesterol depletion. The depleted groups show generally higher red/green ratios in the plasma membranes (Fig. 11 a). We divided the red/green ratio of the front lamellipodia by that of the back lamellopodia to reveal the difference between the two areas; if this value of ratios is 1, no asymmetry is indicated. The value is ∼0.87 in the polarized neutrophils and 0.96 in the cholesterol-depleted neutrophils (Fig. 11 b). The number is closer to 1 after cholesterol depletion, which is consistent with the disruption of raft domains by removal of cholesterol. The data displayed in Fig. 11 c show that the front and rear of the cells have significantly differing emission spectra—approaching the separation obtained from the resolved domains of the natural lipid GUVs (Fig. 7). Significantly, the difference in the front versus the rear spectra is abolished upon cholesterol depletion (Fig. 11 d). This suggests that the spectral difference in the normal polarized cells is a result of a biased distribution of cholesterol toward the leading edge of the cell, as would be associated with a high density of rafts.

FIGURE 11.

Averaged spectral data derived from neutrophil images. (a) Red/green emission ratio of di-4-ANEPPDHQ integrated over the entire plasma membranes in polarized control and cholesterol-depleted neutrophils. (b) Ratio of ratios: red/green values from the lamellipodium (front) are divided by the red/green values from the remainder of the plasma membrane (rear) in polarized neutrophils. In the control group, n = 28; in the cholesterol-deplete, group, n = 25.

In summary, we compared the images from the nonpolarized, polarized, and cholesterol-depleted polarized neutrophils. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ shows a lower red/green ratio in the front lamellipodia of polarized neutrophils relative to the rest of the cell. In cholesterol-depleted cells, this heterogeneity is lost. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ's response is consistent with the results from raft marker staining distribution and laurdan spectroscopy studies. This demonstrates di-4-ANEPPDHQ's ability to detect rafts in living cells.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we have presented a new optical probe, di-4-ANEPPDHQ, for imaging phase-separated domains in lipid membranes. We can use it to differentiate the liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered domains in GUVs with linear and nonlinear imaging methods, namely SPF, TPF, and SHG.

Di-4-ANEPPDHQ shows green and red emission in the ordered and disordered phases, respectively. To further understand the mechanism, we undertook a series of studies with LUVs of different lipid composition and different phases. We found that the dye's emission spectrum is primarily influenced by two factors, cholesterol concentration and the lipid phases. The emission spectrum blue-shifted with cholesterol concentration increase, and it also blue-shifted in the liquid-ordered phase relative to the liquid-disordered phase.

Cholesterol affects lipid membranes in two ways. First, it is known that cholesterol changes the lipid membrane's dipole potential (31,32). Second, it changes the packing of lipid molecules in the membrane (33). Both of these effects could influence di-4-ANEPPDHQ's fluorescence.

Dipole potentials are intramembrane potentials originating from oriented dipoles at the membrane/water interface. The polar molecules contributing to dipole potentials include water, the polar headgroups of lipid molecules, and the ester linkages of acyl chains to the glycerol backbone of phospholipids. Dipole potentials in the membrane bilayer are positive in the center, with a magnitude of several hundred millivolts. Cholesterol increases the dipole potentials, and styryl dyes have been shown to sense the dipole potential changes in lipid membranes (32). In theory, dipole potentials can affect the energy difference between the excited and ground states of dye molecules. Both the excitation and emission spectra would be influenced, and they would be shifted in the same direction and to a similar extent. This has been demonstrated by studying the spectra of another styryl dye, d-4-ANEPPS (32). A cholesterol analog, 6-ketocholestanol, which increases dipole potential (34), blue-shifts di-4-ANEPPS' excitation and emission spectra to a similar extent, amounting to just a few nanometers (32). Interestingly, in our experiments, increasing cholesterol concentration in the LUVs blue-shifts both the excitation and emission spectra of di-4-ANEPPDHQ, but to a much greater extent in the emission spectrum. Therefore, we conclude that cholesterol's influence on the dipole potential contributes to the dye's emission-spectrum shift, but it cannot account for the large magnitude of the shift.

As cholesterol also changes the order of lipids in membranes, a second hypothesis for the origin of the emission shift is that it reflects a change in the local molecular ordering of the dye molecule's environment. Membranes with pure lipid will be in a liquid-disordered phase above their transition temperature and in a solid phase below the transition temperature. Cholesterol in the lipid membrane disrupts molecular packing when the membrane is below the lipid's transition temperature, whereas it orders the acyl chains of lipids when the temperature is higher than the transition temperature. Thus, an intermediate phase, the liquid-ordered phase, has been established for cholesterol-containing membranes (35,36). Therefore, cholesterol could increase the order or rigidity of the molecular environment surrounding di-4-ANEPPDHQ, thereby decreasing the dye's Stokes shift. The Stokes shift reflects the energy lost when the excited dye molecules relax to a lower energy geometry and a lower energy distribution of solvent molecules before emitting fluorescence. Styryl dyes are known to have large Stokes shifts, reflecting the formation of twisted excited states and a large reorganization of solvent around the redistributed charge within the excited state (37,38). When the environment becomes more ordered, conformation change and rearrangement of the solvent may be limited. Therefore, there will be less energy lost and more energy released as fluorescence from dyes in the rigid environment. The data of Fig. 3 could then be explained as an increased order or rigidity in the neighborhood of dye molecules as the cholesterol concentration is increased.

The same hypothesis concerning the Stokes shift could also explain the phase transition's effect on di-4-ANEPPDHQ. The lipid rigidity increases when the membrane phase changes from liquid-disordered to -ordered. In Fig. 4, there is no obvious excitation shift but a large emission blue shift during the phase transition.

Comparing emission spectra from LUVs of DOPC and 7:3 DPPC/cholesterol, there is a 60 nm peak difference. In GUVs of 2:2:1 DPPC/DOPC/cholesterol, the spectra from the ordered and disordered phases have a shift of ∼30 nm, which is smaller than the maximum possible difference of ∼60 nm obtained from the LUV experiments. In the GUVs, the chemical components are not totally segregated into the two phases, so not all the DOPC is in the disordered phase and not all the DPPC and cholesterol are in the ordered phase. Cholesterol in particular does not show dramatically preferential partitioning between the two phases. In GUVs made from 7:7:5 DOPC/DPPC/cholesterol, after phase separation at 25°C, NMR shows that in the ordered phase 32 mol % of the lipid molecules are cholesterol, whereas in the disordered phase 22 mol % of the lipids are cholesterol (39). Although the formula of GUVs used in our experiment (2:2:1 DOPC/DPPC/cholesterol) is slightly different from that used in the NMR study, we would still expect only moderately preferential partitioning of cholesterol into the liquid-ordered phase. Thus, the emission spectrum shift of 30 nm mainly reflects the phase difference rather than a large difference in cholesterol concentration. This also helps explains why the natural lipids (Fig. 7) show a somewhat poorer contrast between the two phase-separated domains in the red and green emission channels. The partitioning of the different lipids between the two phases will be even less clean for this heterogeneous mixture of natural lipids. Furthermore, the more complex lipid mixture will tend to somewhat diminish the order even within the liquid-ordered phase, thus accounting for the red shift of both spectra in Fig. 7 compared to those of Fig. 6. Thus, the LUV spectra represent extremes that can be used to gauge the domain characteristics in the GUVs and in cells.

Di-4-ANEPPDHQ differentiates the two domains not only by its fluorescence but also by its SHG signals. Its higher SHG intensity in the liquid-disordered phase reflects the higher concentration of the dye. The affinity of the dye to LUV composed of DOPC, representing a liquid-disordered membrane, is ∼11 times higher than the affinity for 2:1 DPPC/cholesterol, representing the liquid-ordered phase, at room temperature. If we assume that all the DOPC is in the GUVs' liquid-disordered phase and all the DPPC and cholesterol are in the liquid-ordered phase, we would conclude that the concentration of di-4-ANEPPDHQ in the liquid-disordered phase is 11 times that in the liquid-ordered phase. Thus, based on the quadratic dependence of SHG intensity on concentration (26), we might expect to see the SHG signal intensity in the disordered phase to be 121 times that in the liquid-ordered phase. The relative SHG signal measured in the disordered phase to that in the ordered phase is actually 7:1, which is much smaller than the expected 121:1. It corresponds to only a 2.6-fold higher concentration in the disordered phase. We explain the smaller ratio in two ways. First, the implicit assumption concerning the concentration of lipids in the two phases of the GUVs is not reasonable. As explained above, the lipids do not partition into the two phases with a complete segregation. Therefore, the affinities estimated in LUVs of DOPC and 2:1 DPPC/cholesterol can work only as an upper limit for the GUV experiment. Second, the concentration of the dye is not the only factor influencing the SHG signal intensity. The alignment of the dyes is another important factor. SHG depends on coherent scattering of polar molecules, which need to be aligned in the same orientation, so the signal will be strongest if the dye chromophores are parallel to each other. In the ordered phase the acyl chains are straighter, and the lipids are more tightly packed. This will improve alignment of the dye molecules and increase the SHG signal in the ordered phase, partially counteracting the effect of a higher concentration of the dye in the disordered phase.

In summary, di-4-ANEPPDHQ shows significant fluorescent emission spectrum shifts in liquid-ordered and -disordered phase domains coexisting in GUVs. This appears to primarily reflect the membrane rigidity in the different phases. The dye also shows SHG intensity contrast between the two domains, reflecting both the dye's concentration and alignment in the two phases.

Di-4-ANEPPDHQ has been used to measure the transmembrane potential changes in live cells, and we provide evidence that it can also be used as a probe for rafts in neutrophil plasma membranes. Compared to other probes currently used to study membrane domains in live cells, di-4-ANEPPDHQ has some benefits. First, it loads into cells from a water solution. Most membrane probes are not water soluble, so they need organic solvents, such as DMSO and ethanol, or vehicles, such as Pluronic F127 or γ-cyclodextrin, to be mixed with buffer solutions for cells. These may disturb cell membranes and cause artifacts. Second, the dye loads into cells rapidly. Laurdan requires 30–60 min to stain cells (7), during which period it may be internalized by endocytosis. Signals from intracellular organelles complicate the image analysis. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ stains the plasma membrane rapidly, so the stained cells can be imaged immediately. Before any obvious endocytosis is observed, there is a time window during which clean fluorescent images of plasma membrane can be acquired. The length of the time window depends on the type of cell and the temperature. Furthermore, if rafts are detected by SHG from the dye, the internal staining will not show up in the SHG images. Third, di-4-ANEPPDHQ can be imaged by multiple optical methods, including confocal microscopy with commonly available visible wavelengths. Fourth, di-4-ANEPPDHQ's fluorescence senses the environmental differences between phases, as required for detecting rafts with different chemical components. Probes such as cholera toxin subunit B, which bind to certain chemical components in rafts, may not detect all rafts in cells because of the heterogeneity of rafts. It should be cautioned that, as with other environmentally sensitive probes, the spectrum of di-4-ANEPPDHQ could be influenced by interactions with membrane proteins that cannot be predicted from its spectral characterization in lipid vesicles. However, the fact that the emission spectra originating from the front and rear of the cell are distinct in normal cells (Fig. 11 c), but become indistinguishable in cholesterol-depleted cells (Fig. 11 d), argues that, at least in the case of neutrophils, the dye is sensitive to a differential distribution of cholesterol-enriched raft domains. We anticipate that di-4-ANEPPDHQ will become a valuable probe for visualizing lipid domains in live cells.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Enrico Gratton's lab and Sarah Keller's lab for their suggestions and help.

This study was funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering via a National Institutes of Health grant (No. EB001963).

References

- 1.Veatch, S. L., and S. L. Keller. 2002. Organization in lipid membranes containing cholesterol. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89:268101–268104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons, K., and D. Toomre. 2000. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, D., and J. Rose. 1992. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 68:533–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgart, T., S. T. Hess, and W. W. Webb. 2003. Imaging coexisting fluid domains in biomembrane models coupling curvature and line tension. Nature. 425:821–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagatolli, L., and E. Gratton. 2000. Two photon fluorescence microscopy of coexisting lipid domains in giant unilamellar vesicles of binary phospholipid mixtures. Biophys. J. 78:290–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parasassi, T., E. Gratton, W. Yu, P. Wilson, and M. Levi. 1997. Two-photon fluorescence microscopy of laurdan generalized polarization domains in model and natural membranes. Biophys. J. 72:2413–2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaus, K., E. Gratton, E. P. W. Kable, A. S. Jones, I. Gelissen, L. Leonard Kritharides, and W. Jessup. 2003. Visualizing lipid Structure and raft domains in living cells with two-photon microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:15554–15559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merritt, E., T. Sixma, K. Kalk, B. van Zanten, and W. Hol. 1994. Galactose-binding site in Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) and cholera toxin (CT). Mol. Microbiol. 13:745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galbiati, F., B. Razani, and M. P. Lisanti. 2001. Emerging themes in lipid rafts and caveolae. Cell. 106:403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malinska, K., J. Malinsky, M. Opekarova, and W. Tanner. 2003. Visualization of protein compartmentation within the plasma membrane of living yeast cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:4427–4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pralle, A., P. Keller, E. L. Florin, K. Simons, and J. K. H. Horber. 2000. Sphingolipid-cholesterol rafts diffuse as small entities in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 148:997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorn, H., K. G. Stenkula, M. Karlsson, U. Ortegren, F. H. Nystrom, J. Gustavsson, and P. Stralfors. 2003. Cell surface orifices of caveolae and locaization of caveolin to the necks of caveolae in adipocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:3967–3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pike, L. J. 2004. Lipid rafts: heterogeneity on the high seas. Biochem. J. 378:281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obaid, A. L., L. M. Loew, J. P. Wuskell, and B. M. Salzberg. 2004. Novel naphthylstyryl-pyridium potentiometic dyes offer advantages for neural network analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods. 134:179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fluhler, E., V. G. Burnham, and L. M. Loew. 1985. Spectra, membrane binding, and potentiometric responses of new charge shift probes. Biochemistry. 24:5749–5755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin, L., A. C. Millard, J. P. Wuskell, H. A. Clark, and L. M. Loew. 2005. Cholesterol-enriched lipid domains can be visualized by di-4-ANEPPDHQ with linear and nonlinear optics. Biophys. J. 89:L04–L06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angelova, M. I., S. Soleau, P. Meleard, J. F. Faucon, and P. Bothorel. 1992. Preparation of giant vesicles by external AC electric fields: kinetics and applications. Prog. Colloid Polym. Sci. 89:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veatch, S. L., and S. L. Keller. 2003. Separation of liquid phases in giant vesicles of ternary mixtures of phospholipids and cholesterol. Biophys. J. 85:3074–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowell, C. A., L. Fumagalli, and G. Berton. 1996. Deficiency of Src family kinases p59/61hck and p58c-fgr results in defective adhesion-dependent neutrophil functions. J. Cell Biol. 133:895–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millard, A. C., L. Jin, M.-D. Wei, J. P. Wuskell, A. Lewis, and L. M. Loew. 2004. Sensitivity of second harmonic generation from styryl dyes to transmembrane potential. Biophys. J. 86:1169–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obaid, A. L., L. M. Loew, J. P. Wuskell, and B. M. Salzberg. 2004. Novel naphthylstyryl-pyridium potentiometic dyes offer advantages for neural network analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods. 134:179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silvius, J. R. 1982. Thermotropic phase transitions of pure lipids in model membranes and their modifications by membrane proteins. In Lipid-Protein Interactions. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 23.Vist, M. R., and J. H. Davis. 1990. Phase equilibria of cholesterol/dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine mixtures: 2H nuclear magnetic resonance and differential scanning calorimetry. Biochemistry. 29:451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoffel, W., W. Darr, and K. P. Salm. 1977. Chemical proof of lipid-protein interactions by crosslinking photosensitive lipids to apoproteins. Intermolecular cross-linkage between high-density apolipoprotein A-I and lecithins and sphingomyelins. Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 358:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen, Y. R. 1984. The Principles of Non-Linear Optics. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 26.Millard, A. C., P. J. Campagnola, W. Mohler, A. Lewis, and L. M. Loew. 2003. Second harmonic imaging microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 361:47–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyd, R. W. 2003. Nonlinear Optics. Academic Press, San Diego.

- 28.Wu, D. 2005. Signaling mechanisms for regulation of chemotaxis. Cell Res. 15:52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lockwich, T. P., X. Liu, B. B. Singh, J. Jadlowiec, S. Weiland, and I. S. Ambudkar. 2000. Assembly of Trp1 in a signaling complex associated with caveolin-scaffolding lipid raft domains. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11934–11942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kindzelskii, A. L., R. G. Sitrin, and H. R. Petty. 2004. Cutting edge: optical microspectrophotometry supports the existence of gel phase lipid rafts at the lamellipodium of neutrophils: apparent role in calcium signaling. J. Immunol. 172:4681–4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szabo, G. 1974. Dual mechanism for the action of cholesterol on membrane permeability. Nature. 252:47–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross, E., R. S. Bedlack, and L. M. Loew. 1994. Dual-wavelength ratiometric fluorescence measurement of the membrane dipole potential. Biophys. J. 67:208–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ipsen, J. H., G. Karlstrom, O. G. Mouritsen, H. Wennerstrom, and M. J. Zuckermann. 1987. Phase equilibria in phosphatidylcholine-cholesterol system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 905:162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon, S. A., T. J. McIntosh, A. D. Magid, and D. Needham. 1992. Modulation of the interbilayer hydration pressure by the addition of dipoles at the hydrocarbon/water interface. Biophys. J. 61:786–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philips, M. C. 1972. The physical state of phospholipids and cholesterol in monolayers, bilayers and membranes. In Progress in Surface and Membrane Science. D. A. Cadenhead, editor. Academic Press, New York. 139–221.

- 36.Alecio, M. R., D. E. Golan, W. R. Veatch, and R. R. Rando. 1982. Use of a fluorescent cholesterol derivative to measure lateral mobility of cholesterol in membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:5171–5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ephardt, H., and P. Fromherz. 1989. Fluorescence and photoisomerization of an amphiphilic aminostilbazolium dye as controlled by the sensitivity of radiationless deactivation to polarity and viscosity. J. Phys. Chem. 93:7717–7725. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loew, L. M., L. Simpson, A. Hassner, and V. Alexanian. 1979. An unexpected blue shift caused by differential solvation of a chromophore oriented in a lipid bilayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101:5439–5440. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veatch, S. L., I. V. Polozov, G. Gawrisch, and S. L. Keller. 2004. Liquid domains in vesicles investigated by NMR and fluorescence microscopy. Biophys. J. 86:2910–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.