Abstract

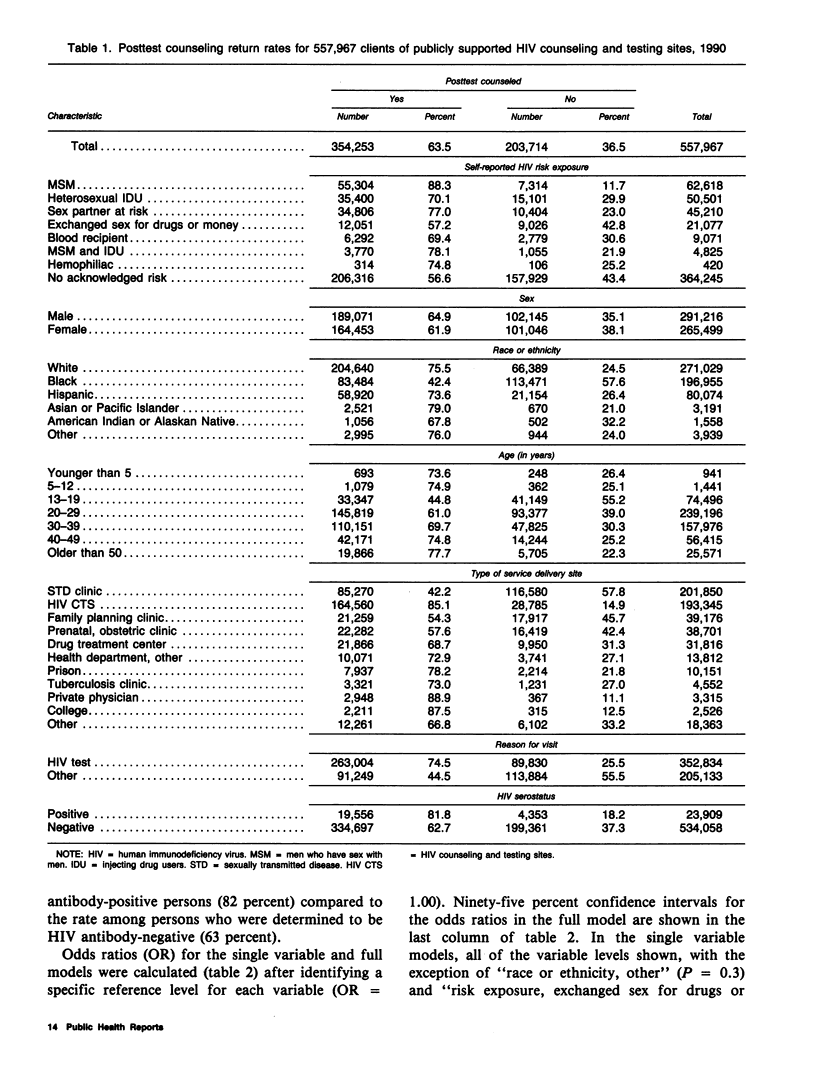

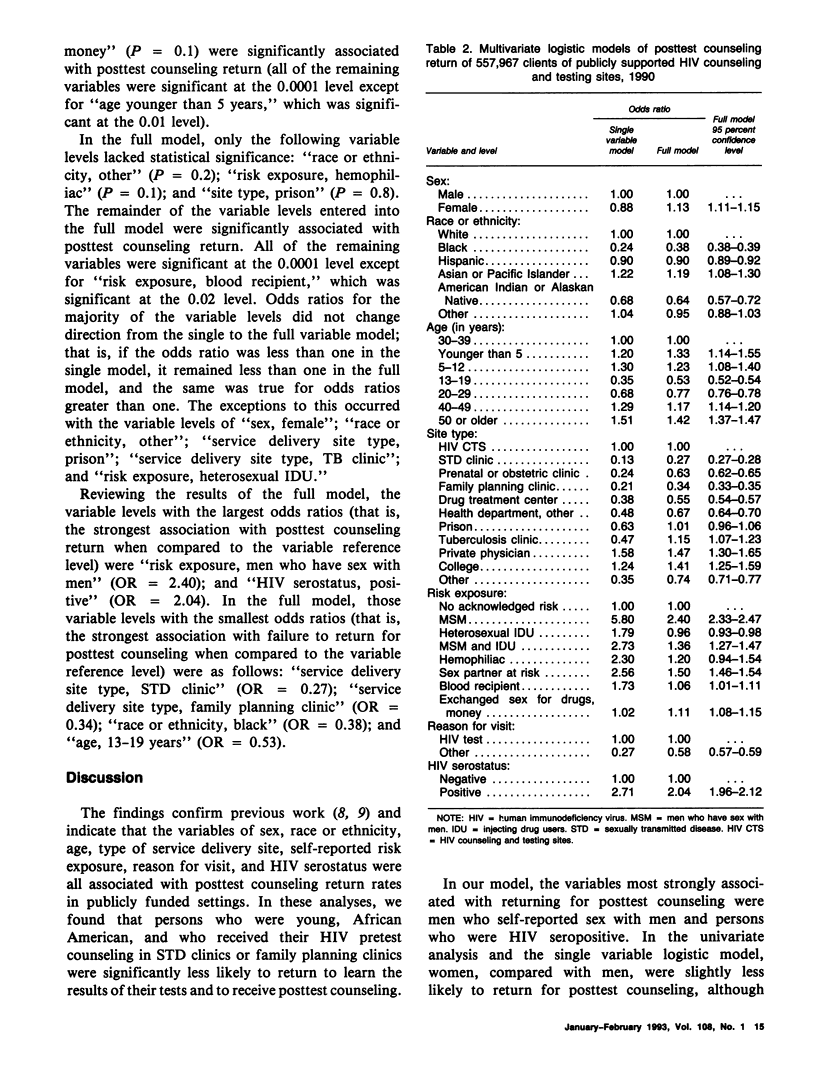

Pretest and posttest counseling have become standard components of prevention-oriented human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody testing programs. However, not all persons who receive pretest counseling and testing return for posttest counseling. Records of 557,967 clients from January through December 1990, representing more than 40 percent of all publicly funded HIV counseling and testing, were analyzed to determine variables independently associated with returning for HIV posttest counseling. On average, 63 percent of clients returned for posttest counseling. The rate varied by self-reported risk behavior, sex, race or ethnicity, age, site of counseling and testing, reason for visit, and HIV serostatus. In multivariate logistic models, persons who were young, African American, and pretest counseled in sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics or family planning clinics were least likely to return for posttest counseling. Those clients who consider themselves to be at risk for HIV infection may be more likely to act on that perception and to follow through with posttest counseling than those who do not perceive risk. Counselors should make special efforts during pretest counseling to encourage adolescents, members of racial or ethnic minorities, and persons seen in STD and family planning clinics to return for posttest counseling by helping them understand and accept their own personal risk of HIV infection. Counselors need to establish, with the client's participation, a specific plan for receiving test results and posttest counseling.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Braveman P., Oliva G., Miller M. G., Schaaf V. M., Reiter R. Women without health insurance. Links between access, poverty, ethnicity, and health. West J Med. 1988 Dec;149(6):708–711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L. K., DiClemente R. J., Reynolds L. A. HIV prevention for adolescents: utility of the Health Belief Model. AIDS Educ Prev. 1991 Spring;3(1):50–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania J. A., Kegeles S. M., Coates T. J. Psychosocial predictors of people who fail to return for their HIV test results. AIDS. 1990 Mar;4(3):261–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenburg W. R. Perceived risk, real risk: social science and the art of probabilistic risk assessment. Science. 1988 Oct 7;242(4875):44–49. doi: 10.1126/science.3175635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack M. S., Lear J. G., Klerman L. Organization of adolescent health services. Study group report. J Adolesc Health Care. 1988 Nov;9(6 Suppl):33S–35S. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(88)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James N. J., Gillies P. A., Bignell C. J. AIDS-related risk perception and sexual behaviour among sexually transmitted disease clinic attenders. Int J STD AIDS. 1991 Jul-Aug;2(4):264–271. doi: 10.1177/095646249100200408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays V. M., Cochran S. D. Issues in the perception of AIDS risk and risk reduction activities by black and Hispanic/Latina women. Am Psychol. 1988 Nov;43(11):949–957. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.11.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbach V. J., Wagner E. H., Karon J. M. The use of epidemiologic data for personal risk assessment in health hazard/health risk appraisal programs. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36(9):625–638. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P. Perception of risk. Science. 1987 Apr 17;236(4799):280–285. doi: 10.1126/science.3563507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]