Abstract

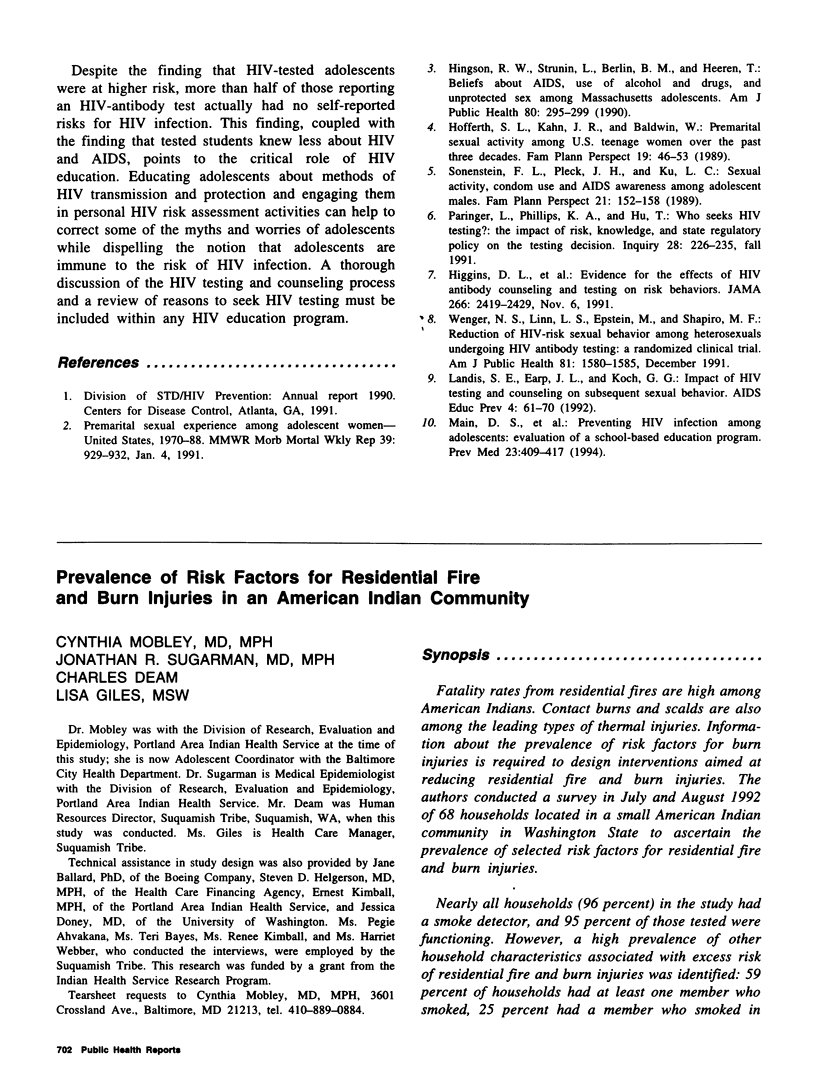

Fatality rates from residential fires are high among American Indians. Contact burns and scalds are also among the leading types of thermal injuries. Information about the prevalence of risk factors for burn injuries is required to design interventions aimed at reducing residential fire and burn injuries. The authors conducted a survey in July and August 1992 of 68 households located in a small American Indian community in Washington State to ascertain the prevalence of selected risk factors for residential fire and burn injuries. Nearly all households (96 percent) in the study had a smoke detector, and 95 percent of those tested were functioning. However, a high prevalence of other household characteristics associated with excess risk of residential fire and burn injuries was identified: 59 percent of households had at least one member who smoked, 25 percent had a member who smoked in bed, 38 percent had a member who drank alcohol and smoked at the same time, 46 percent used wood stoves as a heat source, and 15 percent of households were mobile homes. Thirteen percent of households had at least one fire during the previous 3 years, and the incidence of burns due to all causes and requiring medical treatment was 1.5 per 100 persons per year. Hot water temperature was measured to determine the potential risk for scald burns, and 48 percent of households had a maximum hot water temperature of 130 degrees or more Fahrenheit. Such surveys can guide intervention strategies to reduce residential fire and burn injuries in American Indian communities.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ballard J. E., Koepsell T. D., Rivara F. P., Van Belle G. Descriptive epidemiology of unintentional residential fire injuries in King County, WA, 1984 and 1985. Public Health Rep. 1992 Jul-Aug;107(4):402–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard J. E., Koepsell T. D., Rivara F. Association of smoking and alcohol drinking with residential fire injuries. Am J Epidemiol. 1992 Jan 1;135(1):26–34. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann T. C., Feldman K. W., Rivara F. P., Heimbach D. M., Wall H. A. Tap water burn prevention: the effect of legislation. Pediatrics. 1991 Sep;88(3):572–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland J., Hingson R. Alcohol as a risk factor for injuries or death due to fires and burns: review of the literature. Public Health Rep. 1987 Sep-Oct;102(5):475–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin E., Marchone M., Hanger L., German P. S., Baker S. P. Smoke detector legislation: its effect on owner-occupied homes. Am J Public Health. 1985 Aug;75(8):858–862. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.8.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin E., McGuire A. The causes, cost, and prevention of childhood burn injuries. Am J Dis Child. 1990 Jun;144(6):677–683. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150300075020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierley M. C., Baker S. P. Fatal house fires in an urban population. JAMA. 1983 Mar 18;249(11):1466–1468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patetta M. J., Cole T. B. A population-based descriptive study of housefire deaths in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1990 Sep;80(9):1116–1117. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.9.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan C. W., Bangdiwala S. I., Linzer M. A., Sacks J. J., Butts J. Risk factors for fatal residential fires. N Engl J Med. 1992 Sep 17;327(12):859–863. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209173271207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]