Abstract

We determined the clinical and microbiologic characteristics of community-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia in 19 adult patients. We found that malignancy was the most frequent underlying disease. The overall mortality rate was 58%. All 14 available isolates were identified as genomic species 2 (A. baumannii) by 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing and were found to be genetically distinct by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Acinetobacter baumannii has been documented as an important nosocomial pathogen (6, 9, 16). However, community-acquired A. baumannii complex bacteremia (CAAB) is much less common (3, 5, 7, 8). Most previously reported episodes of CAAB were caused by pneumonia, and relatively few reports have addressed CAAB that arises from other foci of infection (13, 15, 19). In addition, accurate species-level identification of Acinetobacter species is difficult. The commercial identification systems available at present are based on phenotypic methods and do not permit accurate identification to the species level, and four DNA groups (genomic species 1, 2, 3, and 13 of Tjernberg and Ursing) are identified as A. baumannii complex on the basis of these methods alone (14). Recently, a commercial, optimized, genetic method for organism identification based upon 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequence analysis has become available (MicroSeq; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems Division, Foster City, Calif.). Use of this system has been reported to be a good method for genomic species identification of many gram-negative bacilli, including Acinetobacter species (17). To illustrate the microbiologic characteristics, with accurate species identification and clinical manifestations, of CAAB, including those cases not caused by pneumonia, we reviewed all sequential cases of CAAB at our hospital over a 6-year period.

Nineteen adult patients with CAAB presenting to the National Taiwan University Hospital from July 1994 to June 1999 were enrolled in the study. A patient with CAAB was defined as an individual with one or more cultures of blood, collected within 48 h after admission, that were positive for A. baumannii complex, as identified by a biochemical method (14). If the patient had previously been hospitalized, the period between symptom onset and previous discharge had to be greater than 30 days to meet the definition of CAAB. Fourteen bacterial isolates from the patients were preserved at −70°C for further study. The severity of bacteremia at presentation was classified as sepsis, sepsis syndrome, septic shock, and refractory septic shock (1). Preserved bacterial isolates underwent genomic species identification with the MicroSeq system (MicroSeq; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems Division). As previously described in detail (17), identification with this system is based on sequence analysis of the initial 500 bp, located in region A, of 16S rDNA. The susceptibilities of preserved isolates to 15 antimicrobial agents, including piperacillin, piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefpirome, cefepime, aztreonam, amikacin, imipenem, meropenem, gentamicin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and trovafloxacin, were determined by the agar dilution method described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (12). We used a breakpoint of 8 μg/ml for interpretation of the results obtained with cefpirome (11) and a breakpoint of 1 μg/ml for interpretation of the results obtained with trovafloxacin as well as moxifloxacin (2, 10). Otherwise, the criteria proposed by NCCLS were followed for interpretation of the results (12). We used pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to determine the genetic relationships among the preserved isolates. The PFGE method that we used was that described previously (4). The PFGE banding patterns were also interpreted visually by following the criteria proposed previously (18). The outcome of CAAB was classified as mortality if the patient died in the hospital from any cause within 90 days of the bacteremic episode (19). Categorical variables were compared by Fisher's exact test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

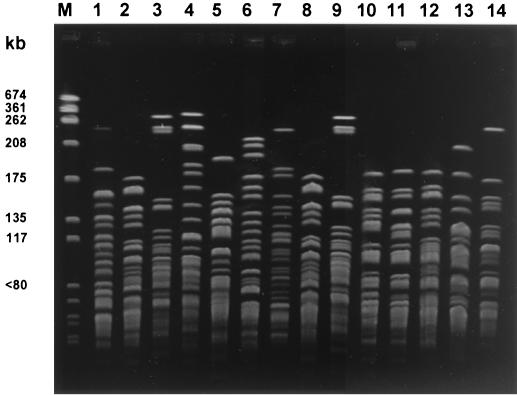

The demographic and clinical data for the 19 patients are described in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 64 years. The ratio of men to women was 2.8/1. Pneumonia was the most frequent primary infection (13 patients in total). Five of 13 patients with pneumonia and 5 of 6 patients with nonpneumonic bacteremia had various underlying malignant diseases. Patients with pneumonia more frequently presented with septic shock and/or refractory septic shock (77 versus 17%; P = 0.041). The median duration from the last hospital discharge to the onset of CAAB for the 11 patients with histories of previous hospitalizations was 134 days. Three patients did not receive effective antimicrobial agents. The median duration from symptom onset to initiation of effective antibiotics among the other 16 patients was 3 days. The overall mortality rate was 58% (11 of 19 patients). Mortality tented to be greater among patients with pneumonia (9 of 13 patients) than among the patients with other underlying conditions (2 of 6 patients; P = 0.14). Early initiation of effective antimicrobial agents (within 3 days after presentation) was not associated with a significantly lower mortality rate (4 of 9 versus 7 of 10 patients; P = 0.370). However, patients presenting with septic shock or refractory septic shock had a significantly higher mortality rate than the patients presenting with other conditions (9 of 11 versus 2 of 8 patients; P = 0.024). All 14 bacterial isolates were proved to be genomic species 2 (A. baumannii) with the MicroSeq system. More than 70% of the isolates were susceptible to the antipseudomonal penicillins, aminoglycosides, ceftazidime, cefepime, cefpirome, new fluoroquinolones, and carbapenem (Table 2). Imipenem and meropenem were the most effective agents. The PFGE results for the 14 isolates are shown in Fig. 1. All 14 isolates were genetically distinct from one another by PFGE analysis.

TABLE 1.

The demographic data and clinical manifestations of 19 patients with CAABa

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/ sex | Underlying disease | Severity of bacteremia | Primary infection focus | No. of previous hospital- izations | Duration (days) from last hospital -ization | Duration (days) from onset to effective treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64/M | Lung cancer, smoking | Refractory septic shock | Pneumonia | Nil | 3 | Mortality | |

| 2 | 71/M | COPD | Refractory septic shock | Pneumonia | 1 | 143 | 4 | Mortality |

| 3 | 55/M | Gastric cancer | Sepsis | Acute cholangitis | 5 | 36 | 3 | Survival |

| 4 | 70/F | DM, ESRD | Refractory septic shock | Pneumonia | 1 | 196 | No effective treatment | Mortality |

| 5 | 85/M | COPD, Smoking | Refractory septic shock | Pneumonia | 2 | 143 | 3 | Mortality |

| 6 | 63/M | Lung cancer, smoking | Septic shock | Pneumonia | 1 | 58 | 1 | Mortality |

| 7 | 65/M | Nil | Septic shock | Pneumonia | Nil | No effective treatment | Mortality | |

| 8 | 67/M | DM, smoking | Septic shock | Pneumonia | 4 | 96 | 3 | Survival |

| 9 | 58/M | NPC, smoking, Port-A catheter | Sepsis | Catheter related | 5 | 33 | 4 | Survival |

| 10 | 32/M | AML after BMT | Sepsis | Enterocolitis | 4 | 279 | 3 | Survival |

| 11 | 80/F | ESRD, DLC | Sepsis | Catheter related | 3 | 56 | 6 | Mortality |

| 12 | 66/F | Lung cancer | Sepsis | Pneumonia | Nil | 17 | Survival | |

| 13 | 57/M | HCC, Liver cirrhosis | Septic shock | SBP | Nil | 11 | Mortality | |

| 14 | 47/M | Alcoholism | Septic shock | Pneumonia | Nil | 3 | Survival | |

| 15 | 47/M | Thymic carcinoma, smoking | Sepsis | Primary bacteremia | 4 | 134 | No effective treatment | Survival |

| 16 | 73/F | Lymphoma, DM | Sepsis syndrome | Pneumonia | 4 | 780 | 3 | Survival |

| 17 | 82/F | Lung cancer | Sepsis syndrome | Pneumonia | Nil | 14 | Mortality | |

| 18 | 39/M | Alcoholism, smoking | Septic shock | Pneumonia | Nil | 6 | Mortality | |

| 19 | 48/M | Alcoholism | Refractory septic shock | Pneumonia | Nil | 2 | Mortality |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-staged renal disease; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; DCL, double-lumen catheter; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

TABLE 2.

MICs, MIC50s, MIC90s, and susceptibility rates for the 14 bacterial isolates to 15 antibiotics

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

Susceptible rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | ||

| Piperacillin | 8-≥256 | 16 | 64 | 71.4 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.03-128 | 4 | 64 | 71.4 |

| Cefotaxime | 8-≥256 | 32 | 64 | 14.3 |

| Ceftazidime | 1-32 | 4 | 8 | 92.9 |

| Cefpirome | 1-64 | 2 | 8 | 92.9 |

| Cefepime | 0.5-32 | 2 | 8 | 92.9 |

| Aztreonam | 64-≥256 | 64 | 128 | 0 |

| Imipenem | 0.125-1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 100 |

| Meropenem | 0.25-2 | 0.25 | 1 | 100 |

| Gentamicin | 0.125-≥256 | 0.5 | 16 | 85.7 |

| Amikacin | 0.25-≥256 | 1 | 1 | 92.9 |

| Ofloxacin | 0.125-16 | 0.25 | 16 | 85.7 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.125-32 | 0.125 | 32 | 85.7 |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.03-16 | ≤0.03 | 8 | 85.7 |

| Trovafloxacin | ≤0.03-8 | ≤0.03 | 8 | 85.7 |

50% and 90%, MICs at which 50 and 90% of isolates, respectively, are inhibited.

FIG. 1.

PFGE banding patterns of the 14 bacterial isolates (lanes 1 to 14, respectively); lane M, molecular weight marker (Staphylococcus aureus NCTC 8325).

Hence, we found that most patients with CAAB presented with pneumonia as their primary infection and that this implied a worse prognosis. CAAB appears to be associated with underlying malignancy in patients, which had also been pointed out by Tilley and Roberts (19). We found that genomic species 2 (A. baumannii) is responsible for all cases of CAAB, but there is no clonal spread of A. baumannii among patients presenting with CAAB. Among the 10 patients in our series with underlying malignancy, 6 had previously been hospitalized. Thus, malignancy may increase the risk of CAAB via multiple means. Malignancy may predispose patients to the development of A. baumannii infection. Alternatively, malignancy as well as other chronic systemic diseases, such as end-stage renal disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, may result in repeated hospitalizations during which patients are more likely to become colonized with A. baumannii, only to develop invasive disease sometime after discharge, even after 30 days postdischarge.

The mortality rate for patients with CAAB without pneumonia has not been reported previously; we found this rate to be 33%, less than half the mortality rate among patients with CAAB resulting from pneumonia. Although the difference in mortality rates among patients with CAAB caused by pneumonia versus that among patients with CAAB and primary infection at other sites was not statistically significant, this is probably due to the small number of patients studied. In conjunction with the greater mortality rate, patients with CAAB due to pneumonia presented with more severe disease.

Previous studies did not indicate the genomic species responsible for the majority of community-acquired acinetobacter infections. Genomic species identification of Acinetobacter spp. on the basis of analysis of the initial 500 bp of 16S rDNA appears to be as effective as identification on the basis of a more complete sequence analysis of 1,500 bp of 16S rDNA (17). Using the MicroSeq system in this way, we found that all 14 bacterial isolates were genomic species 2 (A. baumannii), implying that this is the major genomic species responsible for CAAB in our community.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the following important findings. First, patients with pneumonic CAAB have a worse prognosis than patients with nonpneumonic CAAB. Second, the development of CAAB is associated with underlying malignancy. Third, the A. baumannii genomic species is responsible for the majority of cases of CAAB. Fourth, no evidence of clonal spread of A. baumannii in the community resulted in multiple cases of CAAB. Fifth, ceftazidime, cefepime, cefpirome, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones are the drugs of choice for the treatment of CAAB in Taiwan.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues in the clinical microbiological laboratory of National Taiwan University Hospital for excellent work in the initial identification of the bacterial isolates. In addition, we acknowledge Tsai-Ling Lauderdale and especially Yih-Ru Shiau, of the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan for assistance with the genomic species identification of the isolates.

REFERENCES

- 1.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference Committee. 1992. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 20:864-874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews, J. M., J. P. Ashby, G. M. Jevons, and R. Wise. 1999. Tentative minimum inhibitory concentration and zone diameter breakpoints for moxifloxacin using BSAC criteria. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 44:819-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anstey, N. M., B. J. Currie, and K. M. Withnall. 1992. Community-acquired Acinetobacter pneumonia in the Northern Territory of Australia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, S. C., C. T. Fang, P. R. Hsueh, Y. C. Chen, and K. T. Luh. 2000. Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing liver abscess in Taiwan. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 37:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordes, L. G., E. W. Brink, P. J. Checko, A. Lentnek, R. W. Lyons, P. S. Heyes, T. C. Wu, D. G. Tharr, and D. W. Fraser. 1981. A cluster of Acinetobacter pneumonia in foundry workers. Ann. Intern. Med. 95:688-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glew, R. H., Jr., R. C. Moellering, and L. J. Kunz. 1977. Infection with Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Herellea vaginicola): clinical and laboratory studies. Medicine 56:79-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glick, L. M., G. P. Moran, J. M. Coleman, and G. F. O'Brien. 1959. Lobar pneumonia with bacteremia caused by Bacterium anitratum. Am. J. Med. 27:183-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodhart, G. L., E. Abrutyn, R. Watson, R. K. Root, and J. Egert. 1977. Community-acquired Acinetobacter calcoaceticus var. anitratus pneumonia. JAMA 238:1516-1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jimenez, P., A. Torres, R. Rodriguez-Roisin, J. P. de la Bellacasa, R. Aznar, J. M. Gatell, and A. Agusti-Vidal. 1989. Incidence and etiology of pneumonia acquired during mechanical ventilation. Crit. Care Med. 17:882-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones, R. N. 1994. Preliminary interpretative criteria for in vitro susceptibility testing of CP-99219 by dilution and disk diffusion methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:167-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones, R. N., C. Thornsberry, A. L. Barry, L. Ayers, S. Brown, J. Daniel, P. C. Fuchs, T. L. Gavan, E. H. Gerlach, and J. M. Matsen. 1984. Disk diffusion testing, quality control guidelines, and antimicrobial spectrum of HR 810, a fourth-generation cephalosporin, in clinical microbiology laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:409-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 13.Ng, T. K. C., J. M. Ling, A. F. B. Cheng, and S. R. Norrby. 1996. A retrospective study of clinical characteristics of Acinetobacter bacteremia. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 101(Suppl.):26-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreckenberger, P. C., and A. von Graevenitz. 2000. Acinetobacter, Achromobacter, Acaligenes, Moraxella, Methylobacterium, and other nonfermentative gram-negative rods, p. 539-560. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 15.Siau, H., K. Y. Yuen, P. L. Ho, S. S. Wong, and P. C. Woo. 1999. Acinetobacter bacteremia in Hong Kong: prospective study and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smego, R. A., Jr. 1985. Endemic nosocomial Acinetobacter calcoaceticus bacteremia: clinical significance, treatment, and prognosis. Arch. Intern. Med. 145:2174-2179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang, Y. W., N. M. Ellis, M. K. Hopkins, D. H. Smith, D. E. Dodge, and D. H. Persing. 1998. Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic techniques for identification of unusual aerobic pathogenic gram-negative bacilli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3674-3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tilley, P. A. G., and F. J. Roberts. 1994. Bacteremia with Acinetobacter species: risk factors and prognosis in different clinical settings. Clin. Infect. Dis. 18:896-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]