Abstract

Background

Although many patients with cancer would prefer to die at home, most die in hospital. We carried out a study to describe the yearly trends in the place of death between 1992 and 1997 and to determine predictors of out-of-hospital death for adults with cancer in Nova Scotia.

Methods

In this population-based study, we linked administrative health data from 2 databases — the Nova Scotia Cancer Centre Oncology Patient Information System and the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre Palliative Care Program — for all adults in Nova Scotia who died of cancer from 1992 to 1997. We also used grouped neighbourhood income information from the 1996 Canadian census. Death out of hospital was defined as death in any location other than an acute care hospital facility. We used logistic regression analysis to identify the odds of dying out of hospital over time and to identify factors predictive of out-of-hospital death.

Results

A total of 14 037 adults died of cancer during the study period. The data for 101 people were excluded because of missing information regarding place of death. Of the remaining 13 936 people, 10 266 (73.7%) died in hospital and 3670 (26.3%) died out of hospital. Over the study period the proportion of people who died out of hospital rose by 52%, from 19.8% (433/2182) in 1992 to 30.2% (713/2359) in 1997. Predictors associated with out-of-hospital death included year of death (for 1997 v. 1992, adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–2.0), female sex (adjusted OR 1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.3), age (for ≥ 85 v. 18–44 years, adjusted OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.7–2.8), length of survival (for 61–120 v. ≤60 days, adjusted OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.8–2.6; for 121–180 v. ≤60 days, adjusted OR 2.5, 95% CI 2.2–2.8), having received palliative radiation (adjusted OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7–0.9) and region of death (Cape Breton v. Halifax, adjusted OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.5–0.6). Among Halifax residents, registration in the Palliative Care Program was also a significant predictor of out-of-hospital death (adjusted OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.2–1.7). Tumour group, neighbourhood income and residence (urban v. rural) were not predictive of out-of-hospital death in multivariate analysis.

Interpretation

Over time, more patients with cancer, especially women, elderly people and people with longer survival after diagnosis, died outside of hospital in Nova Scotia.

During the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s substantial reform took place in the health care system across Canada. This reform resulted in a reduction in the number of hospital beds per capita and in length of hospital stay.1,2,3 These changes, combined with the steady increase in numbers of deaths from cancer in the aging Canadian population, have had the potential to exert increased pressure on families to care for terminally ill relatives at home.

If given the choice, up to 80% of patients with cancer would prefer to die at home,4,5,6,7 but the proportion who realize this desire is much smaller.8,9,10,11,12,13 International estimates of the proportion of patients with cancer who die at home range from 23% in Antwerp, Belgium,11 to 26% in the United Kingdom9 to 55% in Australia.12,13 Such studies have shown that people who are elderly, those living in rural areas, those with longer survival after diagnosis and those who receive home care are most likely to die out of hospital.8,12,14 The role of income, sex and tumour type appears less certain.9,12,15

In Canada, among patients referred to a specialized palliative care program, estimates of the proportion who die at home have ranged from 28%16 to 47%.17 The investigators used prospective surveys and found that patient preference and social and professional supports were all associated with dying at home. Two descriptive, population-based Canadian studies demonstrated the beginnings of a trend away from hospital as the place of death.18,19 Population-based data on the relation between demographic characteristics and the services used (palliative care and palliative radiotherapy) are, however, still lacking.

We performed a study to describe the yearly trend in the rate of out-of-hospital death among adults who died from cancer in Nova Scotia from 1992 to 1997. We also determined which factors were predictive of dying out of hospital. Predictors examined included patient demographic characteristics and the use of 2 services: palliative radiation and, for the Halifax region, referral to a palliative care program.

Methods

For this retrospective, population-based study, we created a secondary data file from the linkage of individual-level information from 2 administrative health databases: the Nova Scotia Cancer Centre Oncology Patient Information System (OPIS) and the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre Palliative Care Program. In addition, we used the Postal Code Conversion File and 1996 Canadian census data to create an indicator of urban or rural residence and a proxy for income using neighbourhood income information (enumeration area median income, grouped into quintiles).

The subjects were all adults in Nova Scotia who died of cancer, as identified from the death certificate, from 1992 to 1997. Death certificate information is provided within the Nova Scotia Cancer Registry file, a component of OPIS. We extracted from this database the patient's name, health card number, sex, date of birth, postal code, county of residence, date of cancer diagnosis (date of the pathology report in 90% of cases; in the remaining cases, in which there was no pathology report, the date of diagnosis was the date of the most reliable form of notification of cancer), date of death, cause of death (coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification20), receipt of radiotherapy and place of death (dichotomized as in hospital or out of hospital), as recorded on the death certificate. We used the Palliative Care Program database to determine whether subjects had been registered in the program. We defined hospital death as death that occurred within an acute care hospital facility. “Out of hospital” encompassed all other locations, including the home and long-term care centres. Neither chronic care hospitals nor hospice facilities are available in the province.

We used patient demographic characteristics (health card number, sex and age) to link Palliative Care Program information to data obtained from the OPIS database using a probabilistic record-linkage method. Following this process and before adding census information and analyzing the data, we removed all personal identifying information.

The research ethics committee of the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax, provided ethics approval for the study.

Analysis

Because 74% of the deaths occurred among people aged 65–84 years, we created 5 age groups reflecting this skewed distribution. People aged 65 years or more were classified into 3 groups owing to their large representation in the sample and given previous evidence of less use of the Palliative Care Program by very elderly people.21 We created 5 aggregate groups for tumour type (as coded on the death certificate): breast, lung, colon, prostate (the 4 most frequent tumours) and “other.” The reference group was lung cancer, since it affects both sexes and is one of the most prevalent forms of cancer.22 To account for varying lengths of survival, we categorized the time between diagnosis and death as 60 days or less, 61–120 days, and 121 days or more.

We used cross-tabulations and logistic regression analyses to identify temporal changes in patterns and predictors of place of death. The predictor variables considered were year of death, sex, age, region of death, tumour group, receipt of palliative radiation, registration in the Palliative Care Program, length of survival, place of residence and neighbourhood income quintile. We conducted multivariate logistic regression analyses using manual backward elimination techniques to develop the most parsimonious model of out-of-hospital death. The initial model included all potential predictor variables found in univariate analysis to be significantly associated with out-of-hospital death. Subsequent modelling involved the sequential removal of potential predictors found to no longer be significantly associated with out-of-hospital death in the multivariate model. Variables removed included neighbourhood income quintile and aggregate tumour group.

Because data on referral to the Palliative Care Program were available only for people residing in the metropolitan Halifax region, we limited the use of this predictor to a subanalysis for this region alone.

Results

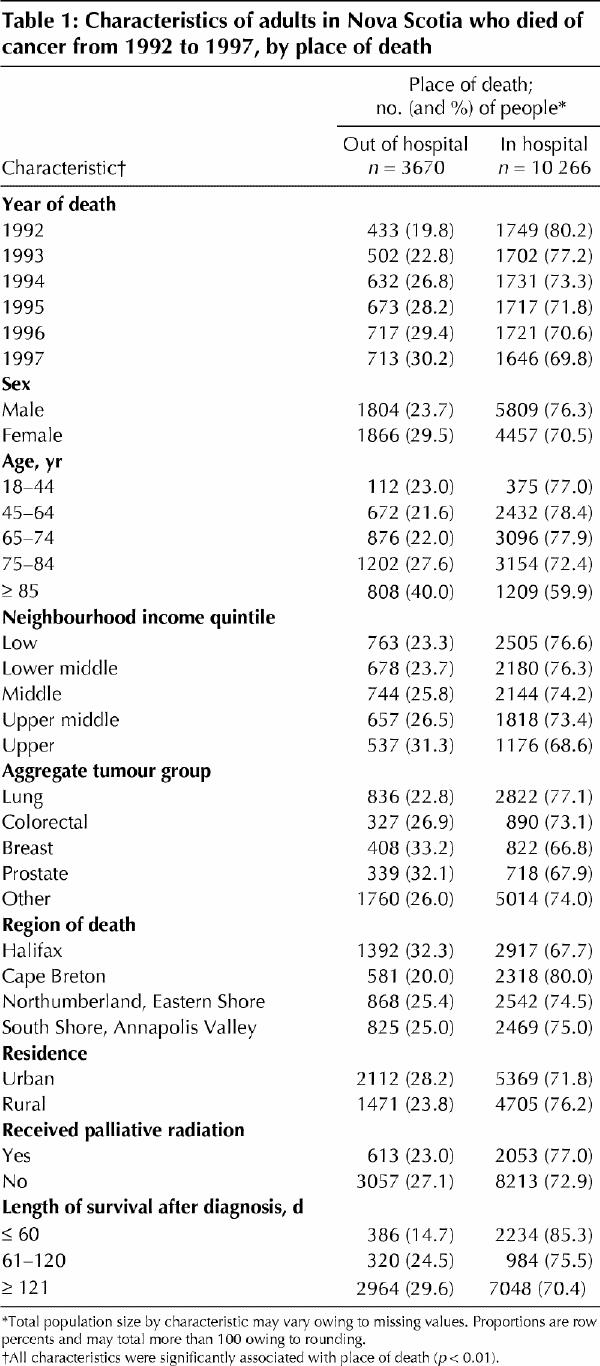

A total of 14 037 adults died of cancer in Nova Scotia during the study period. We excluded the data for 101 people because of missing information regarding place of death. Of the remaining 13 936 people, 10 266 (73.7%) died in hospital, and 3670 (26.3%) died out of hospital. The characteristics of the 2 groups are presented in Table 1. All characteristics were found to be significantly associated with place of death (p < 0.01).

Table 1

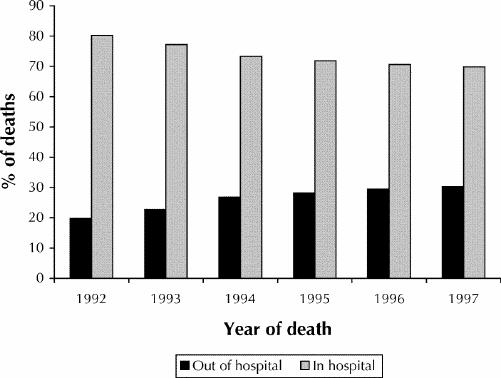

There was a significant trend toward increasing proportion of deaths out of hospital over the study period, from 19.8% (433/2182) in 1992 to 30.2% (713/2359) in 1997 (Fig. 1). Logistic regression analysis confirmed this incremental trend. Compared with 1992, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for dying out of hospital in 1997 was 1.8 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–2.0) (Table 2).

Fig. 1: Proportion of deaths out of hospital and in hospital among adults in Nova Scotia who died of cancer, 1992–1997.

Table 2

Table 2 shows the final adjusted results of the multivariate regression analyses. After all other significant factors in the model were accounted for, people who died out of hospital were more likely to be female, to be 75 years of age or older and to have survived longer than 60 days after diagnosis. Among those who died out of hospital, the adjusted OR for being female was 1.2 (95% CI 1.1–1.3) even though men accounted for 54.6% of all deaths. The adjusted OR for those aged 85 years or more was twice that of those aged less than 45 years (adjusted OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.7–2.8). Those with a longer interval (more than 120 days) from initial cancer diagnosis to death had an adjusted OR of 2.5 (95% CI 2.2–2.8) compared with those who survived 60 days or less.

People who died outside of metropolitan Halifax were much less likely to die out of hospital than those in Halifax. The odds of dying out of hospital among those in the Cape Breton region were almost 50% less (adjusted OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.5–0.6) (Table 2). Having received palliative radiation was also found to be associated with reduced odds of dying out of hospital (adjusted OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7–0.9). In multivariate analysis, aggregate tumour group, neighbourhood income quintile and urban v. rural residence did not prove to be significant predictors of dying out of hospital.

Of the 4309 people within the metropolitan region of Halifax who died of cancer, 1392 (32.3%) died out of hospital, and 2223 (51.6%) were seen at least once by the regional Palliative Care Program. After all other factors retained in the multivariate model were accounted for, people who died out of hospital were more likely than those who died in hospital to have been admitted to the Palliative Care Program (adjusted OR 1.4, CI 1.2–1.7) (Table 2).

Interpretation

We found a shift in place of death among patients with cancer over the study period, from in hospital to outside of hospital. This shift may have had as much to do with how services are delivered in Nova Scotia as with personal choice. The proportion of deaths that occurred out of hospital increased from 19.9% to 30.2%. In addition, women, elderly people, those who survived longer after diagnosis and those referred to the Palliative Care Program were more likely to have died out of hospital. Although it is not possible to tell from administrative data whether the trend is a response to patient demand for care at home or a result of a reduction in hospital bed availability, the latter has been clearly documented.1,2,3,23 In addition, the availability of certain community-based services, namely home care24 and referral to palliative care programs,25 increased substantially during the study period.

In the United Kingdom the rate of home death among patients with cancer changed little from 1985 (27%) to 1994 (26.5%).9 In Belfast specifically, the rate of home death fell from 35% in 1977 to 28% in 1997.26 Concurrently, there was an increase in the rate of death in hospices in the United Kingdom.9 There are no freestanding hospices in Nova Scotia.

There are conflicting reports about the relation between age and location of death. Some investigators have reported that elderly people indicate a preference to die in hospital,27 whereas others have found that elderly people prefer to die at home.28 In our study, people 85 years of age or older were more than twice as likely to die out of hospital as those aged less than 45. Preference likely depends on personal experience, the course of the illness and the availability of local health care services.21 Our data are currently not in a form that allows separation of deaths in long term care facilities from true “in-home” deaths. In the case of sick elderly people who live at home, there is substantial variability in the presence of spouse or children caregivers.14,16,17,29 In the long-term care setting, there is growing recognition of the need to enhance palliative care to better meet the needs of residents. Clearly, with the recently documented increase of 41% in the number of Canadians aged 80 years or more,30 this issue will require greater exploration as specific programs are designed to meet the needs of elderly people.7

In our study, women were more likely than men to die out of hospital. This result is in keeping with the findings of Gilbar and Steiner.28 However, Higginson and colleagues9 found that women were less likely than men to die at home. There is a need to explore geographic and cultural differences between the sexes in the desire for home death.

Cancer patients in Nova Scotia who did not live in the metropolitan Halifax region were much less likely than those who lived in Halifax to die out of hospital. Perhaps an established “culture of caring” leads some communities to care for dying patients in hospital more than other communities. Provincial health reports indicate that Cape Breton has relatively higher volumes of patient-days per 1000 population and longer lengths of stay in acute care facilities than other regions in the province.23 However, this does not explain everything. The Annapolis Valley region, where cancer patients also had a lesser likelihood of dying out of hospital, has relatively fewer patient-days per 1000 and shorter lengths of stay in acute care facilities than Cape Breton does.23 A combination of factors may be contributing to the location of death, including how hospitals are utilized in different regions and the availability of community-based services. What part of a city or region people live in has been found by others to be predictive of location of death.26

Income has variably predicted location of death.15,26 In our study, income was a predictor in the univariate analysis only. Our data suggest that differences by income might be explained by “region” or “age” or both in multivariate analysis. Our finding that people with shorter survival after diagnosis were much more likely to die in hospital than those with longer survival is in keeping with previous reports.8 With limited time to effect interventions, it may be a challenge to establish the care preferences of such ill patients and their family and then organize this care in the home. Nevertheless, as hospitals continue to downsize, we may need to develop more responsive services to meet these “acute” needs.

People who received palliative radiation therapy may have had more complex symptom control needs as well as a greater likelihood of being in hospital for symptom control at the time of death than people who did not receive such therapy. Regarding palliative care programs, we suspect that both greater use of the Palliative Care Program by those desiring to die out of hospital and the focus of the program on keeping people with advanced cancer out of hospital resulted in the positive association between admission to such a program and out-of-hospital death.

Our data were restricted to available administrative sources. In the future we hope to add data on home care, referral to palliative care programs outside the Halifax region, long-term care, metastatic disease sites and patients' stated preferred location of death. In addition, research is needed to determine how home care, primary care and specialized palliative care services are used by those who die out of hospital.

Conclusion

A substantial shift occurred in Nova Scotia between 1992 and 1997 in place of death for people who died from cancer. Given that most people with this disease would prefer their care to be in the community, we have challenges before us. As a nation with an aging population we have a substantial moral responsibility to care for dying people in whatever location best serves their needs. The development of a national palliative care strategy is now on the agenda of the federal government.31 As such a strategy is developed, we will need to develop health policy and service delivery programs that attempt to meet all needs, regardless of age, sex, place of residence and socioeconomic status.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Dr. Burge was involved with the original concept of this project and guided the data acquisition and analysis. He participated in interpretation and discussion of the results, wrote the first draft of the paper and was responsible for subsequent revisions. Ms. Lawson was responsible for the construction of the databases involved in the project and the analytical approach. She was also involved in completing the analysis, presenting the results and contributing to the writing of the first and subsequent drafts of the paper. Dr. Johnston was instrumental in the development of the analytical methods, interpretation of the results and revisions of the paper.

Acknowledgments: This work was supported in part by contributions from the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre Research Foundation and the National Cancer Institute of Canada through Cancer Research and Education in Nova Scotia.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Frederick Burge, Department of Family Medicine, Abbie J. Lane Building 8, 5909 Veterans' Memorial Lane, Halifax NS B3H 2E2; fred.burge@dal.ca

References

- 1.Tully P, Saint-Pierre E. Downsizing Canada's hospitals, 1986/87 to 1994/95. Health Rep 1997;8(4):33-9.

- 2.Transitions in care: Nova Scotia Department of Health facilities review. Halifax: Nova Scotia Department of Health; 2000. Available: www.gov.ns.ca/health/facilities/default.htm (accessed 2002 Dec 13). p. 3 of Annex 1.

- 3.Health care in Canada: a first annual report. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2000. p. 8.

- 4.Dunlop RJ, Davies RJ, Hockley JM. Preferred versus actual place of death: a hospital palliative care support team experience. Palliat Med 1989;3:197-201.

- 5.Townsend J, Frank AO, Fermont D, Dyer S, Karran O, Walgrove A, et al. Terminal cancer care and patients' preference for place of death: a prospective study. BMJ 1990;301:415-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Rural Palliative Home Care Staff and Consultants. A rural palliative home care model: the development and evaluation of an integrated palliative care program in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. A Federal Health Transition Fund Project Report. Halifax: Communications Nova Scotia; 2001. p. 4.

- 7.Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJA. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med 2000;3(3):287-300. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Axelsson B, Christensen SB. Place of death correlated to sociodemographic factors: a study of 203 patients dying of cancer in a rural Swedish county in 1990. Palliat Med 1996;10:329-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Higginson IJ, Astin P, Dolan S. Where do cancer patients die? Ten-year trends in the place of death of cancer patients in England. Palliat Med 1998; 12:353-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching death: improving care at the end of life. Washington: National Academy Press; 1997. p. 45-6. [PubMed]

- 11.Schrijvers D, Joosens E, Vandebroek J, Verhoeven A. The place of death of cancer patients in Antwerp. Palliat Med 1998;12:133-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Hunt R, Bonett A, Roder D. Trends in the terminal care of cancer patients: South Australia, 1981–1990. Aust N Z J Med 1993;23:245-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hunt RW, Bond MJ, Groth RK, King P. Place of death in South Australia: patterns from 1910–1987. Med J Aust 1991;155:549-53. [PubMed]

- 14.Grande GE, Addington-Hall JM, Todd CJ. Place of death and access to home care services: Are certain patient groups at a disadvantage? Soc Sci Med 1998;47(5):565-79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Sims A, Radford J, Doran K, Page H. Social class variation in place of cancer death. Palliat Med 1997;11:369-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.McWhinney IR, Bass MJ, Orr V. Factors associated with location of death (home or hospital) of patients referred to a palliative care team. CMAJ 1995; 152(3):361-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cantwell P, Turco S, Brenneis C, Hanson J, Neumann CM, Bruera E. Predictors of home death in palliative care cancer patients. J Palliat Care 2000; 16(1):23-8. [PubMed]

- 18.Heyland DK, Lavery JV, Tranmer JE, Shortt SED. The final days: an analysis of the dying experience in Ontario. Ann R Coll Physicians Surgeons Can 2000;33(6):356-61.

- 19.Wilson DM, Anderson JC, Fainsinger RL, Northcott HC, Smith SL, Stingl MJ, et al. Social and health care trends influencing palliative care and the location of death in twentieth-century Canada. Final NHRDP report. Edmonton: University of Alberta; 1998.

- 20.International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification. Ann Arbor (MI): Commission on Professional and Hospital Activities; 1992.

- 21.Burge F, Johnston G, Lawson B, Dewar R, Cummings I. Population-based trends in referral of the elderly to a comprehensive palliative care programme. Palliat Med 2002;16(3):255-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Canadian cancer statistics 2001. Toronto: National Cancer Institute of Canada; 2001.

- 23.Annual statistical report 2000/01. Halifax: Performance Measurement & Health Informatics Information Management Branch, Nova Scotia Department of Health; 2002. p. 2, 15, 17. Available (PDF file): www.gov.ns.ca/health/downloads/2000-2001rev2.pdf

- 24.Home care Nova Scotia: update. Halifax: Nova Scotia Department of Health; 1997. p. 1-14.

- 25.Johnston GM, Gibbons L, Burge FI, Dewar RA, Cummings I, Levy IG. Identifying potential need for cancer palliation in Nova Scotia. CMAJ 1998; 158(13):1691-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Davison D, Johnston G, Reilly P, Stevenson M. Where do patients with cancer die in Belfast? Ir J Med Sci 2001;170(1):18-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Zusman ME, Tschetler P. Selecting whether to die at home or in a hospital setting. Death Educ 1984;8:365-81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Gilbar O, Steiner M. When death comes: Where should patients die? Hosp J 1996;11:31-48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Burge FI, McIntyre P, Twohig P, Cummings I, Kaufman D, Frager G, et al. Palliative care by Canadian physicians in the 1990s: resiliency amid reform. Can Fam Physician 2001;47:1989-95. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Profile of the Canadian population by age and sex: Canada ages. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2002 July 16. Cat no 96F0030XIE2001002. Available: www12 .statcan .ca /english/census01/Products/Analytic/companion/age/contents.cfm (accessed 2002 Dec 13).

- 31.Leader of the government in the Senate takes on special responsibility for palliative care [press release]. Ottawa: Prime Minister of Canada Press Office; 2001 Mar 14. Available: www.pm.gc.ca/default.asp?Language=E&Page=newsroom&Sub=NewsReleases&Doc=carstairs.20010314_e.htm (accessed 2002 Dec 13).