Abstract

Esp1396I restriction–modification (RM) system recognizes an interrupted palindromic DNA sequ ence 5′-CCA(N)5TGG-3′. The Esp1396I RM system was found to reside on pEsp1396, a 5.6 kb plasmid naturally occurring in Enterobacter sp. strain RFL1396. The nucleotide sequence of the entire 5622 bp pEsp1396 plasmid was determined on both strands. Identified genes for DNA methyltransferase (esp1396IM) and restriction endonuclease (esp1396IR) are transcribed convergently. The restriction endonuclease gene is preceded by the small ORF (esp1396IC) that possesses a strong helix-turn-helix motif and resembles regulatory proteins found in PvuII, BamHI and few other RM systems. Gene regulation studies revealed that C.Esp1396I acts as both a repressor of methylase expression and an activator of regulatory protein and restriction endonuclease expression. Our data indicate that C protein from Esp1396I RM system activates the expression of the Enase gene, which is co-transcribed from the promoter of regulatory gene, by the mechanism of coupled translation.

INTRODUCTION

The bacterial type II restriction–modification (RM) systems are composed of two enzymatic activities. One of them, DNA methylation activity, ensures the modification of specific DNA sequences, thus preventing the host DNA from the action of the other, endonucleolytic, activity (1). A comparison of cloned and sequenced RM systems has revealed many examples of their horizontal transfer (2,3). The successful establishment of a RM system when entering the new host requires a complete modification of the host’s DNA before the appearance of restriction endonuclease activity, thus the need for tight regulation of genes for restriction and modification enzymes is quite evident. Three mechanisms involved in the regulation of type II RM systems have been described to date. One of them employs the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif identified at the N-terminus of the methyltransferase (Mtase). HTH motif binding to the promoter region can repress the initially high expression of Mtase gene (4,5). A second mechanism exploits the modulation of promoter activity depending on the methylation status of the DNA target sequence which is recognized by the RM system and situated within the promoter region between the methylase and endonuclease (Enase) genes (6). The third mechanism is based on the action of the small protein, designated C, which is encoded by an open reading frame (ORF) found in the vicinity of the conventional restriction and modification genes. In four systems, BamHI, PvuII, Eco72I and EcoRV, the gene for C protein precedes that for Enase and both of them are collinear, whereas the gene for Mtase is located divergently from C. In all four systems C acts either as an activator of Enase expression or both activator of Enase expression and repressor of Mtase expression (7–10). The organization of Kpn2I RM system differs from that of all the aforementioned systems. In Kpn2I, genes for Enase and Mtase converge, whereas the gene for C protein is located upstream from kpn2IM and is transcribed in the opposite orientation. Moreover, the regulatory protein from Kpn2I system was found to be inert with respect to Enase gene expression, but markedly depressed the expression of Mtase gene (11).

This publication describes the cloning, sequence analysis and regulation of the plasmid-borne Esp1396I RM system from Enterobacter sp. strain RFL1396, whose gene organization differs from all RM systems mentioned above. The Esp1396I RM system recognizes an interrupted, palindromic DNA sequence, 5′-CCA(N)5TGG-3′. Esp1396I is the first RM system where the mechanism of coupled translation was demonstrated to be involved in gene regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, phages and media

Enterobacter sp. strain RFL1396 harboring the Esp1396I RM system was provided by Fermentas UAB. Escherichia coli strain RR1 was used as a host in cloning experiments (12). β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) activities were measured using the strain JM109 as a host (13). Plasmids used in this study and their constructs are described in the Supplementary Material. Plasmids obtained in pEsp1396IRM5.6 deletion mapping experiments (Fig. 1A) were constructed by removal of DNA fragments located between the indicated restriction sites. Phage λvir was propagated as described by Sambrook et al. (12). All bacterial strains were cultivated in LB medium (12) and supplemented where needed with the antibiotics ampicillin (Ap, 100 µg/ml), kanamycin (Km, 50 µg/ml), chloramphenicol (Cm, 30 µg/ml), tetracycline (Tc, 15 µg/ml) or streptomycin (Str, 30 µg/ml) at 37°C, except for strain JM109 [pZS-C] which was grown in the presence of 1 mM IPTG and 0.1% L(+)-arabinose both before and after the introduction of pEspM::lacZ.

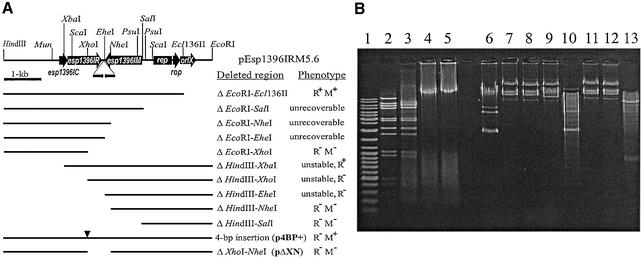

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic map of pEsp1396IRM5.6 plasmid and deletion mapping of genes encoding the Esp1396I RM system. Thin line represents the entire pEsp1396 plasmid cleaved with BglII and inserted into pUC19, which was opened with BamHI. Targets for both HindIII and EcoRI are from pUC19 multiple cloning site. The identified ORFs are shown in accordance with the sequencing data. Directions of transcription of all identified genes are indicated by arrows. Deletion plasmids constructed in this work are indicated below as thin lines and their relevant phenotypes are indicated on the right. Triangle marks the 4-bp insertion introduced at the XhoI site in esp1396IR and resulting in p4BP+. Restriction and modification phenotypes were determined as described under Materials and Methods. M+, Mtase protection from Esp1396I cleavage; M–, no Mtase protection from Esp1396I cleavage; R+, Enase activity; R–, Enase activity not detectable. (B) Restriction and modification activities of cloned genes. Lane 1, DNA ladder; lane 2, λ DNA incubated with Esp1396I; lanes 3–5, λ DNA incubated with crude extracts prepared from cells carrying either pEsp1396IRM5.6 or derivatives p4BP+ and pΔXN, respectively; lanes 6–9, DNAs isolated from cells carrying pUC19, pEsp1396IRM5.6, p4BP+ and pΔXN, respectively; lanes 10–13, the same as in lanes 6–9 but after the incubation with Esp1396I.

Enzymes and cloning techniques

Restriction enzymes, DNA modifying enzymes, kits and DNA size markers were produced at and used as recommended by Fermentas UAB. [α-33P]dATP was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Plasmid DNAs were prepared by the alkaline lysis method (15). The remaining RNA was removed using the procedure of DNA binding to glass milk (16). Restriction and deletion mapping, as well as other DNA manipulations, were carried out using standard procedures (12). Escherichia coli transformations were carried out by the CaCl2 technique (12).

DNA sequence determination, analysis and comparison of deduced amino acid sequences

Plasmid pEsp1396 was prepared for sequencing by subcloning of overlapping fragments into pUC19. Unidirectional deletions of subcloned fragments were obtained with the help of ExoIII/S1 Deletion Kit (Fermentas UAB). Dideoxy sequencing reactions (14) were carried out using the Cycle Reader™ DNA Sequencing Kit (Fermentas UAB). The comparison of determined nucleotide and their deduced amino acid sequences with the entries of EMBL and SWISSPROT databases was carried out using the FASTA similarity search program (17); alignment of deduced amino acid sequences was performed using the CLUSTALW program (18). Search for potential HTH motifs was performed using the Dodd–Egan algorithm (19). mRNA secondary structure predictions were carried out using the PCFold 4.0 program.

Functional analysis of restriction and modification activities

Phage λvir mixed with top-layer agarose (0.4% agarose, 0.5% NaCl, 0.5% MgCl2), pre-cooled to 55°C, was used to prepare LB plates (106 phage particles per plate) and subsequently used to test the ability of clones to restrict phage λvir propagation in vivo. Restriction endonuclease in vitro activity was evaluated using crude cell extracts which were prepared and tested as described (20), by using λ DNA as a substrate in 10 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl and 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, pH 7.5 at 37°C. Esp1396I-specific in vivo modification was tested by plasmid DNA incubation with an excess of Esp1396I restriction endonuclease followed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

β-Galactosidase measurements

The activity of β-Gal was determined according to the procedure described by Miller (21) except that rich LB broth was used instead of 1× A minimal medium. pEspM::Lac was toxic to the host in the absence of regulatory protein, thus the technique based on the gradual decrease of the intracellular concentration of regulatory protein during the culture growth (11) was used to determine the effect of esp1396IC on the expression of esp1396IM’::’lacZ gene. Briefly, 2.5 ml of JM109 [pEspM::Lac+pZS-C], from an overnight culture grown in the presence of Plac/ara-1 inducers IPTG (1 mM) and (+)l-arabinose (0.1%), was inoculated into 50 ml of LB broth either with or without 0.05% arabinose and 1 mM IPTG and further incubated for 9 h at 37°C. The probes of both cultures were collected at different time points and used to determine the activity of β-Gal in Miller units (21).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cloning of the esp1396IM and esp1396IR genes

Type II RM systems are encoded by two or more neighboring genes which are sometimes found on naturally occurring plasmids. Enterobacter sp. RFL1396 was examined for the presence of plasmids and the plasmid pEsp1396 of 5.6 kb was isolated and mapped. The restriction endonucleases BglII, SalI, XbaI and XhoI were found to have unique restriction targets on pEsp1396 and were used to cleave the pEsp1396 DNA for insertion into the multiple cloning site of pUC19. Only plasmids obtained after the ligation of BglII-linearized pEsp1396 with BamHI-cleaved pUC19 had the expected insert of 5.6 kb; this recombinant plasmid was named pEsp1396IRM5.6. It conferred to the host cells both the Mtase and Enase activities of Esp1396I specificity, since isolated plasmid DNA was protected from R.Esp1396I challenge in vitro (Fig. 1B, lanes 7 and 11) and RR1 cells carrying the plasmid pEsp1396IRM5.6 restricted the propagation of phage λvir in vivo, whereas their crude cell lysates had R.Esp1396I activity in vitro (Fig. 1B, lane 3).

DNA sequence of pEsp1396

The results of precise localization of restriction and modification genes on the cloned fragment by deletion mapping of pEsp1396IRM5.6 (Fig. 1A) were somewhat confusing and contradictory. Three deletions from the end of the cloned fragment, which is adjacent to the unique Ecl136II target (ΔEcoRI–SalI, ΔEcoRI–NheI and ΔEcoRI–EheI), were unrecoverable and therefore suggested the presence of the methylase gene in this region. However, three deletions from the other end of the cloned fragment (ΔHindIII–XbaI, ΔHindIII–XhoI and ΔHindIII–EheI) produced small translucent colonies for which restriction mapping revealed multiple rearrangements. Therefore, it was impossible to unambiguously determine the methylation status of the isolated plasmids. Moreover, lysates prepared from cells transformed with a pEsp1396IRM5.6 derivative containing the deletion ΔHindIII–XbaI demonstrated detectable activity of R.Esp1396I, while two other derivatives were restriction-deficient. Those observations indicated that the toxicities of HindIII–XhoI and HindIII–EheI deletion derivatives were not dependent on the expression of restriction endonuclease gene.

In order to clarify the above ambiguities, we sequenced the entire fragment corresponding to pEsp1396 linearized at a unique BglII target. The 5622 bp sequence was determined on both strands (EMBL accession no. AF527822). Sequence analysis revealed two large convergent ORFs and three small ORFs (Fig. 1A). Introduction of four extra nucleotides within the first large ORF (see Fig. 1A, derivative p4BP+) resulted in a total loss of restriction endonuclease activity, however the methylation status of isolated DNA was not changed (Fig. 1B, lanes 4, 8 and 12). According to these observations the first large ORF, esp13961R (nt 1713–2636), coded for Esp1396I Enase (307 amino acids, predicted molecular weight 35.1 kDa). The second gene, esp1396IM (nt 3712–2714), was located on the complementary DNA strand. Removal of the 3′-terminal part of this reading frame (Fig. 1A, deletion ΔXhoI–NheI) resulted in the disappearance of modification phenotype (Fig. 1B, lanes 9 and 13), suggesting that esp1396IM encoded a Mtase of 332 amino acids (predicted molecular weight 38.5 kDa). In concordance with this prediction, the Mtase was found to share homology with the large group of m6A-Mtases (data not shown) and belongs to their D21 group (22). There is a unique A base in each DNA strand of Esp1396I target 5′-CCA(N)5TGG-3′ so it should be methylated if Mtase is m6A-specific. In order to verify this presumption we applied the technique of DNA cleavage interference at overlapping targets, which was described in more detail in our previous paper (20). We introduced into the plasmid pACYC184 (details on the construction are available under request) sequence 5′-CCAAGCTTTGG-3′ in which the target for Esp1396I (underlined) overlaps by 1 nucleotide (A base) with that for HindIII (bold). HindIII is known to be sensitive to the methylation of the first A base of its target even if only one DNA strand is methylated (20). We found that the diagnostic site of resulting plasmid is efficiently cleaved with HindIII when DNA was isolated from RR1 cells, however, it is completely HindIII-resistant when DNA was isolated from RR1 cells carrying the plasmid pEsp1396IRM5.6 in trans (data not shown). These results allow us to suppose that Esp1396I Mtase indeed modifies A base. The 3′-terminal ends of these two genes are separated by a 77 bp region, which contains two inverted repeats (nt 2686–2698 and 2700–2712) and has a potential to form a stem–loop structure. Hence, this region could serve as a transcription terminator for both esp1396IR and esp1396IM. The gene for Esp1396I Enase is preceded by the small ORF (nt 1481–1720), which overlaps the 5′-terminus of esp1396IR gene by 8 nucleotides and encodes a protein of 79 residues (C.Esp1396I; predicted molecular weight 9.2 kDa). Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence revealed that C.Esp1396I possesses a strong HTH motif according to the Dodd and Egan weight matrix method (19) and shares a 40–50% homology with the regulatory proteins found in some other RM systems including BamHI and PvuII (23,24). DNA region rep, which is presumably responsible for the replication of pEsp1396 (nt 4026–4518), was discovered based on a high level of similarity (84% identity in 493 nt overlap) to the replication region of E.coli plasmid p15A (25). Immediately downstream from the rep region two small collinear ORFs were identified (Fig. 1). The first of them, rop (nt 4551–4745), codes for a protein of 64 amino acid residues, which is highly homologous (>50%) to a number of Rop/Rom proteins involved in the control of copy number in many plasmids, including that of the E.coli plasmid ColE1 (26). The second ORF (orfX; nt 4745–5176) encodes a protein of 143 amino acid residues (molecular weight 15.8 kDa) which has no homologous proteins of known function. OrfX possesses a strong HTH-like motif (calculated standard deviation score of 7.1) in its N-terminal part (data not shown).

Nucleotide sequence analysis data show that deletions resulting in the unstable plasmids (see Fig. 1A) eliminate either esp1396IC or both esp1396IC and esp1396IR, therefore the observed instability of shortened derivatives can most likely be attributed to the disregulated expression of the Mtase gene.

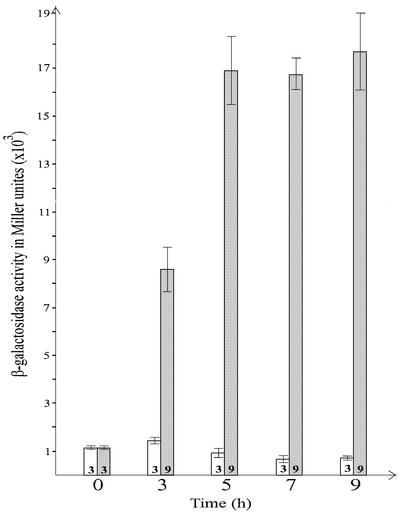

C.Esp1396I represses expression of esp1396IM gene

Deletion mapping suggested that the product of esp1396IC, C.Esp1396I, is involved in the regulation of Mtase gene expression. We attempted to construct a translational esp1396IM’::’lacZ fusion expecting to monitor the activity of hybrid β-Gal both in the presence and in the absence of regulatory protein. However, the plasmid pEspM::Lac resulted in very small and translucent colonies in the absence of regulatory gene, suggesting that uncontrolled expression of esp1396IM’::’lacZ is also toxic to the host. In order to resolve the toxicity problem, we placed the gene for regulatory protein under the control of tightly repressible promoter Plac/ara-1 and used the resulting plasmid pZS-C for the transient synthesis of regulatory protein as described in our previous paper (11). JM109 cells harboring both pEspM::Lac and pZS-C were cultivated either in the presence of Plac/ara-1 inducers arabinose and IPTG or in their absence. β-Gal activities measured at various times of cultivation in the presence of inducers (Fig. 2) demonstrated an insignificant increase of activity in the first 3 h followed by a 2-fold decrease over the next 6 h. In contrast, JM109 cells grown in LB media without inducers exhibited a steady increase in β-Gal activity, which reached a maximal activity of ∼17 000 U in 5 h and maintained this level for an additional 4 h. The increase in β-Gal activity was accompanied by an almost complete arrest of culture growth after 7 h of cultivation (data not shown). It is noteworthy that the addition of either arabinose or IPTG or both to LB had no effect on the toxicity of pEspM::Lac to the host in the absence of pZS-C.

Figure 2.

Effect of C.Esp1396I on the expression of esp1396IM gene. Bacterial strain harboring both plasmid pEspM::Lac (contains esp1396IM’::’lacZ gene fusion) and plasmid pZS-C (contains functionally active gene for regulatory protein under the control of Plac/ara-1) was cultivated either with or without of Plac/ara-1 inducers arabinose and IPTG. Open columns indicate β-Gal activity expressed in Miller units in the presence of both inducers (C.Esp1396I synthesis activated) measured at the time points indicated on the bottom of the scheme; shaded columns indicate β-Gal activity obtained at the same time points in the absence of both inducers (C.Esp1396I synthesis repressed). Numbers at the bottom of each column represent the total number of probes measured in three independent experiments for each time point; thin line at the top of each column indicates standard deviation.

Altogether, the data indicated that a significant increase in the activity of β-Gal depended on a derepression of the esp1396IM promoter which controlled the expression of esp1396IM’::’lacZ in pEspM::Lac and that C.Esp1396I was a repressor of the Mtase gene promoter. Moreover, the arrest of culture growth indicated that uncontrolled expression from the esp1396IM promoter was the most probable reason of plasmid toxicity observed in the deletion mapping experiments.

C.Esp1396I activates the expression of its own gene

Only the regulatory protein C.PvuII from the PvuII RM system was tested for the effect on the expression of its own gene (24) and shown to be an autogenous activator. To gain more understanding on the regulatory mechanisms of differently organized RM systems we determined the effect of C.Esp1396I on the expression of both its own gene and a gene for Enase (see below). The activity of β-Gal produced by plasmid pEspC::Lac in which esp1396IC’ was fused with ’lacZ was measured in the presence and the absence of pBR-C providing esp1396IC gene with its own promoter in trans (Table 1). A 48-fold increase of β-Gal activity was observed in the presence of the gene for C.Esp1396I, which clearly indicated: (i) the product of regulatory gene activated its own synthesis, and (ii) the DNA region (190 bp from Esp1396I RM system preceding the structural part of esp1396IC), which was subcloned together with the 5′ end of esp1396IC’ to yield pEspC::Lac, possessed the nucleotide sequence(s) necessary for C-mediated activation.

Table 1. Effect of C.Esp1396I on expression of esp1396IC and esp1396IR gene fusions.

| Plasmid with gene fusion investigated | Auxiliary plasmid | Localization of regulatory genea | β-Gal activityb |

|---|---|---|---|

| pEspC::Lac (esp1396IC’::’lacZ) | pBR322 | – | 6.3 ± 0.39 (9) |

| pEspC::Lac (esp1396IC’::’lacZ) | pBR-C | In trans | 301 ± 16.2 (8) |

| pEspCR::Lac (esp1396IR’::’lacZ) | pBR322 | In cis | 63.6 ± 7.0 (9) |

| pEsp+4CR::Lac (esp1396IR’::’lacZ) | pBR322 | – | 0.46 ± 0.07 (9) |

| pEsp+4CR::Lac (esp1396IR’::’lacZ) | pBR-C | In trans | 2.41 ± 0.21 (9) |

| pEsp+12CR::Lac (esp1396IR’::’lacZ) | pBR322 | – | 4.6 ± 0.56 (9) |

| pEsp+12CR::Lac (esp1396IR’::’lacZ) | pBR-C | In trans | 82 ± 8.6 (9) |

aPlasmid pEspCR::Lac contains an active regulatory gene; –, regulatory gene in these cells is absent.

bValues indicate mean activities of hybrid β-Gal in Miller units; ±, the standard error; numbers in parentheses represent the total number of probes measured in three independent experiments.

Effect of C.Esp1396I on the expression of restriction endonuclease gene

In nearly all C protein-encoding RM systems, which have been characterized so far, the gene for regulatory protein precedes that for Enase, suggesting their cotranscription and simultaneous regulation at the transcriptional level. However, these predictions were experimentally confirmed only in the case of PvuII system (24). The observation that C.Esp1396I activates the expression of its own gene was the reason to speculate that, if the genes for C and for Enase are transcribed as an operon, the C.Esp1396I should also activate the expression of the Enase gene. In order to test this possibility, the translational fusion esp1396IR’::’lacZ preceded by the wild-type esp1396IC (and its 190 bp control region) was constructed. Escherichia coli cells carrying the resulting plasmid pEspCR::Lac (esp1396IC gene is provided in cis) produced 64 U of β-Gal (see Table 1). The insertion of four extra nucleotides within the coding region of esp1396IC (plasmid pEsp+4CR::Lac) introduced a frameshift that caused C.Esp1396I polypeptide synthesis to terminate 103 nucleotides upstream from the authentic esp1396IC stop codon. This mutation was followed by >135-fold decrease in activity of hybrid β-Gal encoded by the downstream gene (see Table 1). Providing a wild-type gene for regulatory protein in trans (plasmid pBR-C) had just a partial effect on the expression of the fused gene, since only a 5-fold increase in β-Gal activity was observed (Table 1). These findings suggested the existence of additional mechanism(s), besides transcriptional regulation, which are involved in the regulation of the downstream gene for Esp1396I Enase. There are no Esp1396I targets within regulatory regions, which were investigated in this study, thus the specific methylation seems not to be the case.

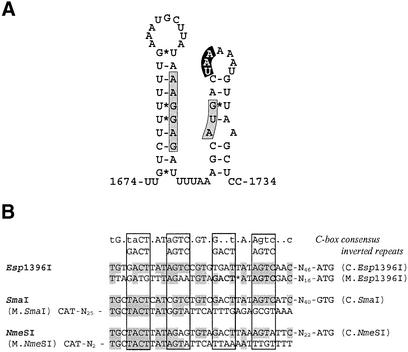

Bacterial genes that code for functionally related products are often cotranscribed in a polycistronic mRNA, which is then translated into the protein products. There are many examples in which translation of the preceding gene is necessary for the efficient translation of a subsequent gene. This phenomenon, called translational coupling, has been observed for the first time in the tryptophan operon of E.coli (27). As in many cases when translational coupling took place, genes for Esp1396I regulatory protein and for Enase overlap each other. In order to test the possibility that esp1396IR is translationally coupled to the esp1396IC gene the plasmid pEsp+12CR::Lac was constructed. It differs from pEsp+4CR::Lac by an extended insertion within the gene for the regulatory protein (12 nucleotides instead of 4 nucleotides) resulting in a restored reading frame. A 10-fold increase in β-Gal activity was observed when translation of the mutant esp1396IC gene was terminated at the same position as in the wild-type gene (Table 1). The mutant C protein encoded by pEsp+12CR::Lac contained four extra amino acids in its middle part and was inactive, as assessed by independent ancillary experiments (data not shown). Therefore, the most likely explanation for the 10-fold increase in β-Gal activity was the restoration of coupled translation resulting in a more efficient translation of the second cistron (esp1396IR’::’lacZ) in conditions of unregulated (basal) transcription from the promoter, located upstream from the first cistron (esp1396IC). Activation of a ribosome binding site (RBS) via translational coupling has been found in many other polycistronic systems, and the principle of activation, at least in some cases, is a breakdown of mRNA secondary structure which masks an RBS of the distal cistron by the upstream translating ribosome (28). Computer analysis of possible secondary structures involving the region that surrounds the 5′-terminus of esp1396IR suggested that a double-stranded mRNA structure with a ΔG = –7.1 could conceivably form and block ribosome access to the Shine–Dalgarno region (Fig. 3A). This observation supports the speculation that esp1396IC and esp1396IR are translationally coupled; however, additional confirmatory experiments are required.

Figure 3.

Elements presumably involved in regulation of Esp1396I RM system genes. (A) Predicted secondary structure of polycistronic mRNA encoding esp1396IC and esp1396IR gene junction. Shine–Dalgarno region and translation start codon for esp1396IR gene are indicated by the gray boxes, stop codon for esp1396IC is indicated by the black box. (B) Putative operator sequences for C.Esp1396I protein. C-box sequences identified upstream esp1396IC and esp1396IM genes as well as those found upstream regulatory and Mtase genes in SmaI and NmeSI RM systems are aligned. Consensus sequence for C-box and for inverted repeats as proposed in (24) is given above. Regions of inverted repeats in the other C-boxes are boxed. Nucleotides matching those indicated as consensus are shaded. Only one inverted repeat found upstream the esp1396IM gene is bolded.

Introduction of the wild-type gene for regulatory protein (plasmid pBR-C) into cells harboring the plasmid pEsp+12CR::Lac elevated the activity of β-Gal from 4.6 to 82 U (Table 1) and even slightly exceeded the activity determined for pEspCR::Lac, in which the esp1396IC gene is located in cis. Taken together, all the data indicated that the regulatory protein from Esp1396I RM system positively regulated the expression of the Enase gene and, most probably, performed this function by regulating the transcription of the dicistronic mRNA from its own promoter as in the case of the PvuII system (24). The existence of such dicistronic mRNA in both Enterobacter sp. RFL1396 and E.coli [pEsp1396IRM5.6] was tested by RT–PCR. cDNA was synthesized from mRNA isolated from both strains with the help of random hexamer primers and subsequently used as a template for PCR amplification using Taq polymerase and a pair of primers, one of which corresponded to the 5′-terminus of esp1396IC gene and the other one was complementary to the middle part of esp1396IR gene. Amplification of the DNA region flanked by these primers is possible only if the same mRNA (and corresponding cDNA) molecule contains the sequence information on both primers. The DNA fragment of expected size and structure was readily amplified, clearly indicating that at least a fraction of mRNA, which is specific for Enase contains also a region coding for regulatory protein (data not shown).

C.Esp1396I operator sequences and mode of action

The negative effect of the esp1396IC gene product on the expression of Mtase gene and its positive effect on the expression of both esp1396IC and esp1396IR indicated the presence of at least two operator sequences for C.Esp1396I. One of them should be located upstream of the esp1396IM gene whereas the other one should be upstream of the esp1396IC gene. Indeed, these so called ‘C-boxes’ (9,24) where identified at the suspected positions by using comparative sequence analysis. The putative C-box upstream from the regulatory gene (Fig. 3B) matched very well with the consensus sequence which was derived from the comparison of putative operator sequences found in five other RM systems (24). It is noteworthy that the detected C-box comprised two copies of inverted tetranucleotide repeats (however, only the 5′ repeat is perfect), each of which representing the putative recognition target for regulatory protein, which presumably acts as a homodimer (24). It should be noted that the putative C-box found upstream from the Mtase gene differed markedly from the consensus of the operator sequences since it matched only one half of the consensus sequence and contained just one inverted repeat. Moreover, the structure of the C-boxes found in two other systems, SmaI and NmeSI (29), which are organized and perhaps regulated like Esp1396I, is identical. These systems exhibit regulatory genes, which are preceded by operator sequences that possess two copies of inverted repeats. In contrast, the genes for Mtases are preceded by C-boxes with the only one copy of repeats (Fig. 3B). The importance of these differences for the regulation of Mtase and Enase genes remains to be defined experimentally.

In summary, it is possible to predicate that after the entry of Esp1396I RM system into a new host an immediate high level expression of the methylase gene is triggered accompanied by the weak expression of the regulatory protein and, most likely, by Enase gene transcription and translation. Since type II restriction endonucleases usually function as homodimers (1), the background level of Enase synthesis should not be toxic to the host cell until the Enase concentration becomes favorable for dimerization. Furthermore, during the establishment of the RM system in a new host the expression of both C gene and Enase gene should increase until the regulatory protein concentration reaches a maximal level, determined by the strength of derepressed promoter. At the same time, an increase in the repressor concentration should result in the gradual repression of the methylase gene to the level determined by the leakage of the methylase gene promoter in repressed state. Such a mechanism should ensure both a delayed appearance of the Enase during the system establishment and its maximal activity later, when the RM system is required for protection from the incoming exogenous DNA. A drop-off of the initially high methylase synthesis to a level sufficient for maintenance of methylation would also be beneficial, since it lowers the possibility for the incoming exogenous DNA to undergo methylation. It is noteworthy that similar regulation modes have been described not only for RM systems regulated by the C proteins (9,23), but also for systems regulated either by the HTH motif localized at the N-terminus of the methylase protein (4) or by the state of methylation of the RM system recognition site localized in the intergenic region (6).

It should be noted that regulation of the Esp1396I RM system has been studied in a heterologous background. Nevertheless, both Enterobacter and Escherichia are members of the Enterobacteriaceae family and we believe that there are no major differences in regulation of the Esp1396I genes in these two backgrounds, but this has yet to be confirmed.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Fermentas UAB for providing enzymes, kits and the Enterobacter sp. strain RFL1396 harboring the Esp1396I RM system. We also thank Hermann Bujard for kindly providing plasmid pZS*24-MCS-1. The authors would like to thank Mr Michael Batenjany for linguistic help. This work was supported by grant from the Lithuanian national research program ‘Molecular basis of Biotechnology’.

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF527822

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson G.G. (1991) Organization of restriction-modification systems. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 2539–2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeltsch A. and Pingoud,A. (1996) Horizontal gene transfer contributes to the wide distribution and evolution of type II restriction-modification systems. J. Mol. Evol., 42, 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee K.F., Shaw,P.C., Picone,S.J., Wilson,G.G. and Lunnen,K.D. (1998) Sequence comparison of the EcoHK31I and EaeI restriction-modification systems suggests an intergenic transfer of genetic material. Biol. Chem., 379, 437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Som S. and Friedman,S. (1993) Autogenous regulation of the EcoRII methylase gene at the transcriptional level: effect of 5-azacytidine. EMBO J., 12, 4297–4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler D. and Fitzgerald,G.F. (2001) Transcriptional analysis and regulation of expression of the ScrFI restriction-modification system of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris UC503. J. Bacteriol., 183, 4668–4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beletskaya I.V., Zakharova,M.V., Shlyapnikov,M.G., Semenova,L.M. and Solonin,A.S. (2000) DNA methylation at the CfrBI site is involved in expression control in the CfrBI restriction-modification system. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3817–3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks J.E., Nathan,P.D., Landry,D., Sznyter,L.A., Waite-Rees,P., Ives,C.L., Moran,L.S., Slatko,B.E. and Benner,J.S. (1991) Characterization of the cloned BamHI restriction modification system: its nucleotide sequence, properties of the methylase, and expression in heterologous hosts. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 841–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao T., Bourne,J.C. and Blumenthal,R.M. (1991) A family of regulatory genes associated with Type II restriction-modification systems. J. Bacteriol., 173, 1367–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rimseliene R., Vaisvila,R. and Janulaitis,A. (1995) The eco72IC gene specifies a trans-acting factor which influences expression of both DNA methyltransferase and endonuclease from the Eco72I restriction-modification system. Gene, 157, 217–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakayama Y. and Kobayashi,I. (1998) Restriction-modification gene complexes as selfish gene entities: roles of a regulatory system in their establishment, maintenance, and apoptotic mutual exclusion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 6442–6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lubys A., Jurenaite,S. and Janulaitis, A. (1999) Structural organization and regulation of the plasmid-borne type II restriction-modification system Kpn21 from Klebsiella pneumoniae RFL2. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 4228–4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 13.Yanish-Perron C., Vieira,J. and Messing,J. (1985) Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene, 33, 103–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanger F., Nicklen,S. and Coulson,A.R. (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 74, 5463–5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birnboim H.C. and Doly,J. (1979) A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 7, 1513–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marko M.A., Chipperfield,R. and Birnboim,H.C. (1982) A procedure for the large-scale isolation of highly purified plasmid DNA using alkaline extraction and binding to glass powder. Anal. Biochem., 121, 382–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson W.R. and Lipman,D.J. (1988) Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 2444–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson J.D., Higgins,D.G. and Gibson,T.J. (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodd I.B. and Egan,J.B. (1990) Improved detection of helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motifs in protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 5019–5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubys A., Lubiene,J., Kulakauskas,S., Stankevicius,K., Timinskas,A. and Janulaitis,A. (1996) Cloning and analysis of the genes encoding the type IIS restriction-modification system HphI from Haemophilus parahaemolyticus. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 2760–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller J.H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 22.Timinskas A., Butkus,V. and Janulaitis,A. (1995) Sequence motifs characteristic for DNA [cytosine-N4] and DNA [adenine-N6] methyltransferases. Classification of all DNA methyltransferases. Gene, 157, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ives C.L., Nathan,P.D. and Brooks,J.E. (1992) Regulation of the BamHI restriction-modification system by a small intergenic open reading frame, bamHIC, in both Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol., 174, 7194–7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vijesurier R.M., Carlock,L., Blumenthal,R.M. and Dunbar,J.C. (2000) Role and mechanism of action of C.PvuII, a regulatory protein conserved among restriction-modification systems. J. Bacteriol., 182, 477–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selzer G., Som,T., Itoh,T. and Tomizawa,J. (1983) The origin of replication of plasmid p15A and comparative studies on the nucleotide sequences around the origin of related plasmids. Cell, 32, 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cesareni G., Muesing,M.A. and Polisky,B. (1982) Control of ColE1 DNA replication: the rop gene product negatively affects transcription from the replication primer promoter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 79, 6313–6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oppenheim D. and Yanofsky,C. (1980) Translational coupling during expression of the tryptophan operon in Escherichia coli. Genetics, 95, 785–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blumer K.J., Ivey,M.R. and Steege,D.A. (1987) Translational control of phage f1 gene expression by differential activities of the gene V, VII, IX and VIII initiation sites. J. Mol. Biol., 197, 439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bart A., Dankert,J. and van der Ende,A. (1999) Operator sequences for the regulatory proteins of restriction modification systems. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 1275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.