Abstract

Human X-ray cross-complementing group 1 (XRCC1) is a single-strand DNA break repair protein which forms a base excision repair (BER) complex with DNA polymerase β (β-Pol). Here we report a site- directed mutational analysis in which 16 mutated versions of the XRCC1 N-terminal domain (XRCC1-NTD) were constructed on the basis of previous NMR results that had implicated the proximity of various surface residues to β-Pol. Mutant proteins defective in XRCC1-NTD interaction with β-Pol and with a β-Pol–gapped DNA complex were determined by gel filtration chromatography and a gel mobility shift assay. The interaction surface determined from the mutated residues was found to encompass β-strand D and E of the five-stranded β-sheet (βABGDE) and the protruding α2 helix of the XRCC1-NTD. Mutations that included F67A (βD), E69K (βD), V86R (βE) on the five-stranded β-sheet and deletion of the α2 helix, but not mutations within α2, abolished binding of the XRCC1-NTD to β-Pol. A Y136A mutant abolished β-Pol binding, and a R109S mutant reduced β-Pol binding. E98K, E98A, N104A, Y136A, R109S, K129E, F142A, R31A/K32A/R34A and δ-helix-2 mutants displayed temperature dependent solubility. These findings confirm the importance of the α2 helix and the βD and βE strands of XRCC1-NTD to the energetics of β-Pol binding. Establishing the direct contacts in the β-Pol XRCC1 complex is a critical step in understanding how XRCC1 fulfills its numerous functions in DNA BER.

INTRODUCTION

X-ray cross-complementing group 1 (XRCC1) is a single-strand break DNA repair protein which is found in eukaryotic species ranging from insects to humans (1–4) and is composed of an N-terminal domain, a central, breast cancer susceptibility protein-1 C-terminal (BRCT) domain (BRCT-I), and a C-terminal BRCT domain (BRCT-II). XRCC1 has no known enzymatic activity but provides multiple functions in DNA base excision repair (BER) that include assembly of DNA repair complexes containing DNA polymerase β (β-Pol), poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and DNA ligase III (reviewed in 5). It is thought that by binding β-Pol and damaged DNA, XRCC1 may protect the template strand at the site of DNA damage, such that short patch repair can proceed efficiently (6). XRCC1 knockout mouse embryos die at day 6.5, and both XRCC1 and β-Pol are required for embryonic development (7). Hamster cell lines carrying defective XRCC1 are sensitive to a number of DNA damaging agents, such as UV, X-ray and ethyl-methyl sulfate (EMS), and display a ten-fold increase in sister chromatid exchange (1,3).

XRCC1 forms a heterodimer with DNA ligase III in cells via a C-terminal BRCT-II domain with a C-terminal BRCT domain in ligase III (8,9) and stabilizes ligase III (10). BRCT-II of XRCC1 has also been reported to have DNA binding activity (11). Mutations in the BRCT-II domain of XRCC1 render cells defective in single-strand break repair in G0 and G1, but the same mutations do not affect XRCC1-dependent repair in S phase (4). The central BRCT-I domain of XRCC1 interacts with the PARP in the poly-(ADP-ribosyl)ated state (12–14). Recently, XRCC1 was also shown to interact with polynucleotide 5′-kinase/3′-phosphatase (PNK), which performs 3′-end processing at the damaged DNA ends to yield the 3′-OH group (15).

Single-strand breaks in DNA arise from exposure to DNA-damaging agents, from endogenous free radicals, and as intermediates in the BER pathway. If not repaired, these breaks can accumulate and be converted into the potentially lethal double-strand breaks. BER involves steps that include removal of a damaged base by a damage specific DNA glycosylase; phosphodiester backbone cleavage by AP endonuclease (APE1) to yield single-strand break DNA with a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) group; DNA synthesis and dRP excision by β-Pol; and ligation by XRCC1/DNA ligase III. DNA breaks caused by DNA damaging agents in the cell are likely detected by PARP, an abundant protein that binds to various strand breaks via its two N-terminal Zn-fingers. PARP may recruit XRCC1/DNA ligase III, β-Pol and other proteins involved in processing damaged ends (reviewed in 16–18).

The repair of the single-strand break can follow alternative pathways differing in the number of nucleotides excised/ re-synthesized. In ‘short-patch’ repair, a single nucleotide is added by β-Pol (19), and dRP is excised by the N-terminal, dRP lyase domain of β-Pol (20). In the ‘long-patch’ pathway, 4–6 nucleotide synthesis is catalyzed by β-Pol (21). FEN-1 is responsible for removal of the 5′-flap and DNA ligase I performs ligation.

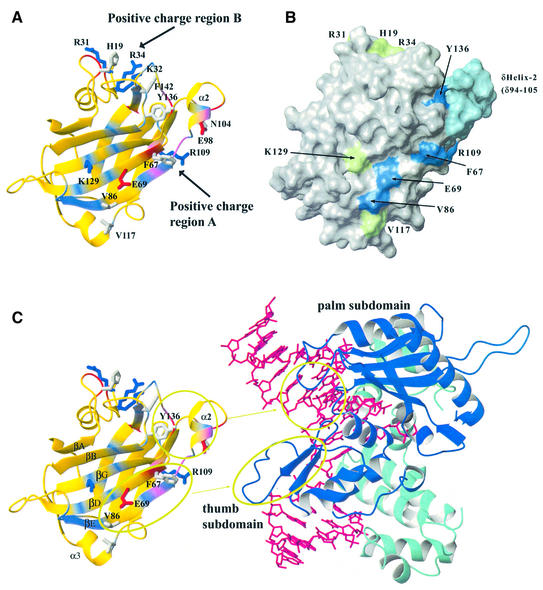

In order to assess residue-specific contributions to β-Pol binding by the XRCC1 N-terminal domain (XRCC1-NTD), we selected for site-directed mutagenesis, amino acid residues that displayed NMR chemical shift changes on binding the β-Pol 22 kDa domain or DNA (6). The NMR chemical shift mapping (CSM) effects can result from direct contacts or indirect perturbation and thus indicate overall surfaces of interaction on proteins. A hydrophobic surface of the protein containing a K129/E69 charge pair (Fig. 1A) had been identified as a region of possible contact with β-Pol and two orthogonal surfaces with positive charge patches, separated by the protruding α2 helix, were identified as the interaction regions with bent DNA, leading to a model that has been refined on the basis of the mutagenesis results presented here (Fig. 1C). Thus, using the CSM data as a guide, the following mutant proteins were constructed: V86R, F67A, E69K, E69K/K129E and V117R at the hydrophobic surface; δ-helix-2 (deletion of residues 94–105), E98K, E98A, N104A at the α2 helix, Y136A adjacent to α2; R109S, and K32A, R31A/K32A/R34A, H19A and F142A within a region that was proximal to upstream DNA and the palm of β-Pol in the ternary complex model. A surface depiction of the residues mutated is shown in Figure 1B. The mutant proteins were designed to either disrupt a hydrophobic contact with β-Pol or to disrupt an ionic interaction by eliminating or reversing charge at a residue. Through biochemical experiments and yeast two-hybrid analysis, the XRCC1-NTD had been shown to interact specifically with the palm-thumb domain of β-Pol with binding being localized predominantly to the C-terminal thumb subdomain (22). The refined docking model (Fig. 1C) now describes specific amino acid residues and secondary structure of the XRCC1-NTD that directly contribute to β-Pol palm-thumb binding.

Figure 1.

The NMR solution structure of the XRCC1-NTD (residues 3–151) showing residues proposed and determined to function in β-Pol binding. (A) The XRCC1-NTD is shown as a yellow ribbon and is colored on the basis of NMR CSM effects in which blue represents residues with changes in NMR resonances as a result of β-Pol 22 kDa domain binding, red represents residues with changes in NMR resonances as a result of gapped 26mer DNA binding, and violet represents residues with changes determined for residues in both experiments. Side chains of residues, that were mutated for this study, are displayed as thick sticks and colored as follows: Arg and Lys, (blue); Asp and Glu, (red); and all other residue types, (gray). (B) Surface diagram of the XRCC1-NTD, residues 3–151. The surface is colored to represent the effects of mutations on the interaction with β-Pol. Residues for which mutations cause a defect in β-Pol binding are colored blue; the α2 helix, deletion of which abolishes β-Pol binding, is colored light blue; and residues that on mutation have no effect on β-Pol binding are colored green. The figure was generated using MOLMOL (25). (C) Model for XRCC1-NTD contacts with β-Pol showing side chains for residues that contribute to β-Pol binding as determined by site-directed mutagenesis. The ribbon for the XRCC1-NTD is colored as described in (A). The residues and α2 helix that contribute to β-Pol binding are circled and the corresponding regions of proposed contact with β-Pol are shown. For β-Pol the 22 kDa palm-thumb domain is colored blue and the fingers domain and the N-terminal 8 kDa domain are colored light blue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and site-directed mutagenesis

pET23a(δE-P)-X157 was constructed by cloning a PCR product, coding for the first 157 residues of human XRCC1 (XRCC1-NTD1–157), between the NdeI and EcoRI sites of a modified pET23a vector (Novagen), pET23a(δE-P). The PCR product was generated from X-183-pET23a (6) by introduction of a stop codon and an EcoRI restriction site after codon 157. The pET23a(δE-P) vector was constructed by deletion of the fragment between the unique Eco47III and PvuII sites, thereby eliminating these sites. A silent unique AflII restriction site was introduced near the end of the coding sequence for XRCC1-NTD. This site allows for the ready transfer of mutations from pET23a(δE-P)-X157 into a vector carrying the gene for full-length XRCC1. Mutations in XRCC1-NTD1–157 were introduced into pET23a(δE-P)-X157 by PCR, the Unique-Site Elimination Kit (Promega) or by long-prime 2-step PCR. The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Expression and purification of proteins

Wild-type and mutant XRCC1-NTD1–157, herein referred to as the XRCC1-NTD, were overexpressed from the corresponding plasmids in BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells at 37°C, as described for XRCC1-NTD1–183 (6), unless otherwise stated. Residues 158–183 of XRCC1 do not form part of the folded domain and are not involved in β-Pol binding. Some of the mutant proteins were partially or completely insoluble when expressed at 37°C and were expressed at 27 or 20°C. The proteins were purified using steps that included ammonium sulfate precipitation at 60 and 77% saturation, followed by gel filtration on a G-50 Sephadex column, as described (6). Further purification was performed by ion exchange chromatography on a SP Sepharose column. Wild-type XRCC1-NTD and the majority of the mutant proteins did not bind to the SP Sepharose at 100 mM NaCl. The V86R and E98A mutants eluted at 200 mM NaCl. The E98K mutant eluted between 200 and 300 mM NaCl, co-purifying with a minor contaminating DNA-binding protein. The proteins were estimated, by Coomassie Blue staining, to be >95% pure, except for K129E which was >80% pure. 15N-labeled proteins for NMR studies were expressed on a minimal medium supplemented with 15NH4Cl, as described previously (6).

NMR spectroscopy

The NMR spectra were collected on four-channel Varian INOVA 600 or 500 NMR spectrometers. Felix 97 (Molecular Simulations, Inc.) was used for data processing and XEASY (23) was used for analysis. Protein samples containing wild-type or mutant 15N-labeled XRCC11–157 were exchanged into NMR buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.5 or 6.8, 400 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 0.4 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonylfluoride (AEBSF) in 90% H2O/10% D2O]. Final protein concentrations ranged from 50 µM to 2.5 mM, depending on the solubility and stability of the mutant proteins. Two-dimensional 1H–15N HSQC spectra were collected for the mutant proteins at 25 or 20°C. Three-dimensional 15N-edited NOESY spectra were collected at 25°C for the K32A, V86R, N104A, R109S, and V117R mutants using a mixing time of 150 ms.

Gel filtration HPLC

Gel filtration HPLC experiments were performed essentially as described for the binding of the XRCC1-NTD to the β-Pol 31 kDa domain (22). The KD for wild-type and mutant XRCC1-NTD binding to the β-Pol 22 kDa domain was determined from the concentration dependence of the apparent molecular mass of the complex. Molecular mass standards (Bio-Rad) were used for determination of apparent molecular masses. In the gel filtration assay, 20 µl samples of wild-type or mutant XRCC1-NTD, alone or in 1:1 molar ratio with the β-Pol C-terminal 22 kDa domain were applied to a 300 mm Bio-Sil SEC 125 column (Bio-Rad) or a Superose 12 HR 10/30 column (Pharmacia) and run at 1 ml min–1 in 50 mM Na+ phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT. The apparent molecular masses for the XRCC1-NTD mutant interaction with the β-Pol 22 kDa domain were determined at 20 µM and 200 µM. Additional concentrations of the two proteins were used in the gel filtration experiments for obtaining dissociation constants for the wild-type XRCC1-NTD and for the E98A and R109S mutants.

Electrophoretic gel mobility shift assay

The experiments were performed as previously described (6), with minor modifications. A 39mer DNA substrate with a one-nucleotide gap was used. The oligonucleotides were HPLC purified and purchased from Oligos, Etc. The downstream primer was 5′-phosphorylated. In performing the assay, the DNA substrates (15 nM) were incubated with 10 nM β-Pol (Trevigen) and the wild-type or mutant XRCC1-NTD for 15 min in 20 µl of binding buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS, 10 mM DTT, 20 µg ml–1 BSA and 7.5% glycerol). The wild-type or mutant XRCC1-NTD proteins were used at concentrations as indicated in Figure 4. The samples were loaded on 12% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and subjected to electrophoresis in 0.5× TBE at 200 V. Chemiluminescent labeling and detection kits (Boehringer Mannheim) were used for visualization of DNA according to manufacturer’s instructions.

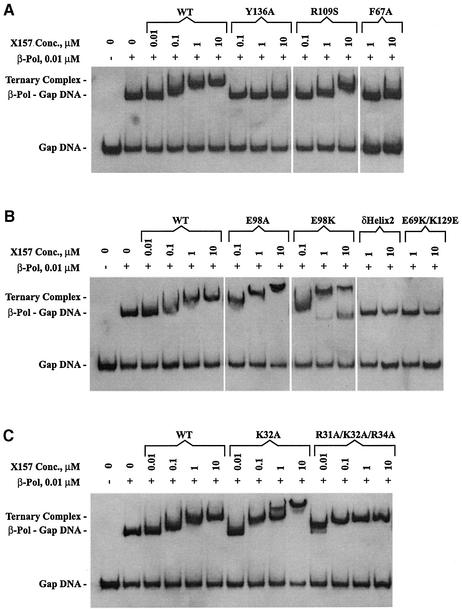

Figure 4.

Gel mobility shift analysis of the binding of XRCC1-NTD1–157 (X157) to the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex. Wild-type or mutant X157 was added, at the indicated concentrations, to β-Pol (10 nM) and 39mer DNA with a one-nucleotide gap (15nM) and binding was observed as supershifting of the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex. The higher-migrating bands observed in E98A, E98K (B) and K32A (C) are probably due to binding of more than one molecule of X157 and/or aggregation. The additional, lower band in E98K (B) is caused by a contaminant co-purifying with the E98K mutant (see Materials and Methods).

RESULTS

Folding, solubility, and temperature sensitivity of the XRCC1-NTD mutants

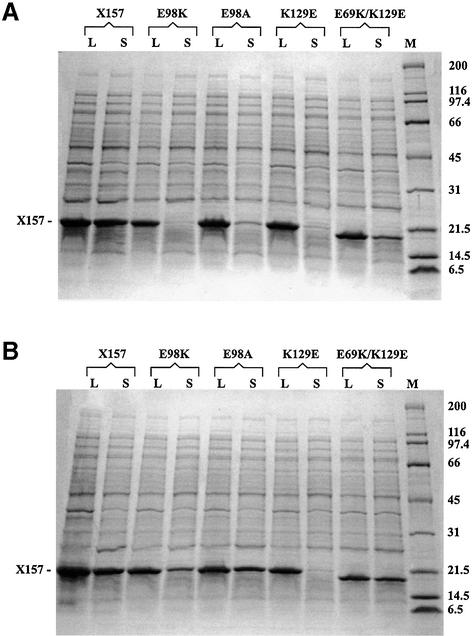

For the XRCC1-NTD mutants, the solubility of the proteins on expression in Escherichia coli was determined, and native folded states of the mutated protein domain were verified before further studies of the effect of the mutation on β-Pol binding. The V86R, F67A, E69K, V117R, K32A and H19A mutants displayed wild-type expression of soluble protein. The δ-helix-2, Y136A, R109S, N104A, F142A, K129E, R31A/K32A/R34A, E98A and E98K XRCC1-NTD mutants showed temperature sensitivity toward expression of soluble protein (Fig. 2). For the temperature sensitive expression mutants little or no expression of soluble protein was observed at 37°C and differing degrees of expression that approached the levels of wild-type were observed at either 27 or 20°C (Table 1). For mutant proteins showing temperature sensitivity, precipitation of the purified mutant proteins was observed at temperatures >20°C. The E98K mutant protein showed the most severe temperature sensitivity, with no soluble protein expressed in E.coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells at 37°C (Fig. 2A). Less than 50% of soluble E98K XRCC1-NTD was obtained on growth at 20°C (Fig. 2B). No soluble E98R mutant was expressed at 37°C, and for the E98A mutant, <20% soluble protein was expressed at 37°C. For the K129E mutant, little soluble protein (<2–5% of the protein) was produced at 37°C and expression of soluble protein was not changed at 20°C. Thus, the K129E mutant was predominantly insoluble irrespective of temperature. The E69K/K129E double mutant had partially restored solubility when expressed at 20°C as compared with 37°C, unlike the K129E single mutant (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Expression of XRCC1-NTD1–157 (X157) mutant proteins at 37 and 20°C. (A) Total lysate (L) and soluble fraction (S) of wild-type X157 and the E98K, E98A, K129E, and E69K/K129E mutants expressed at 37°C in E.coli BL21/plysS cells. M, molecular mass markers. (B) Same as in (A), except that the proteins were expressed at 20°C. The samples were run on 10–20% gradient SDS–PAGE gels.

Table 1. β-Pol 22kDa domain binding and temperature sensitivity for XRCC1-NTD1–157 (X157) mutants.

| KD (µM) | Temperature sensitivitya | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type X157 | 0.3 | wild-type |

| V86R | ndb | wild-type |

| F67A | nd | wild-type |

| E69K | nd | wild-type |

| E69K/K129E | nd | + |

| δHelix2 | nd | ++ |

| Y136A | nd | ++ |

| R109S | 9 | + |

| N104A | 0.3 | ± |

| V117R | 0.3 | wild-type |

| K32A | 0.3 | wild-type |

| F142A | 0.3 | ± |

| H19A | 0.3 | wild-type |

| K129E | 0.3 | + |

| R31A/K32A/R34A | 0.3 | ++ |

| E98A | 0.07 | ++ |

| E98K | 0.3 | +++ |

aTemperature sensitivity, upon expression and in solution, was as follows: ± slight; + moderate; ++ strong; +++ very strong. The K129E mutant and the E69K/K129E mutant (but to a lesser extent) have an additional defect in solubility during expression that is independent of temperature.

bnd, KD could not be determined, because no binding was observed or the binding was weak.

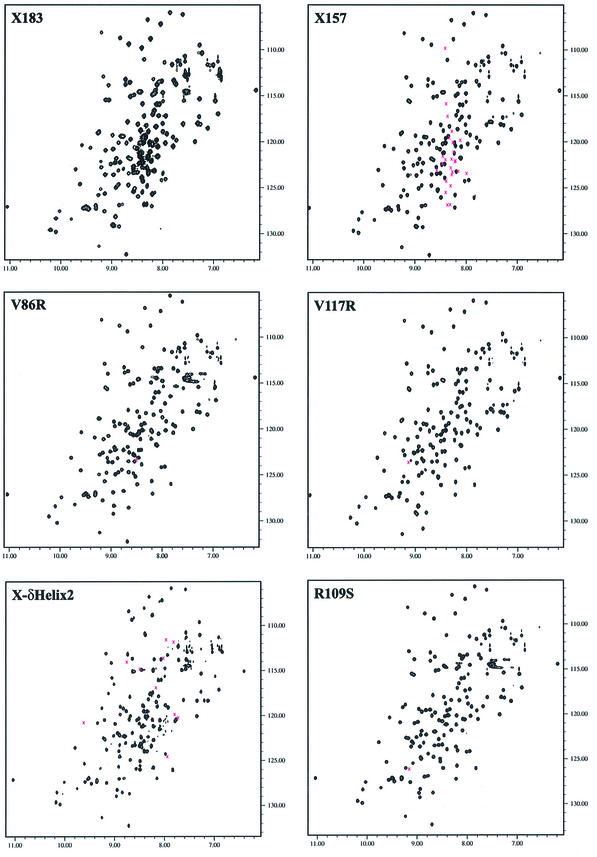

The temperature sensitivity of the expression of soluble mutant proteins suggested the possibility of unfolding at temperatures >20°C. In order to ensure that the mutations were affecting function and not folding, the folded state of the mutant proteins was determined using 2D 1H–15N HSQC NMR spectroscopy. In the 1H–15N HSQC spectrum, the backbone NH group of every residue gives rise to a peak whose position is dependent on the surrounding residues and the conformation of the protein. Therefore, the 1H–15N HSQC spectrum can be used as a unique fingerprint of the protein. The 1H–15N HSQC spectra of all mutant proteins were well dispersed, indicative of a folded protein, and further, nearly all peak positions were identical or highly similar to those of wild-type XRCC1-NTD. Shown are representative 1H–15N HSQC spectra for the wild-type XRCC1-NTD and the V86R, V117R, R109S and δ-helix-2 mutants (Fig. 3). In cases where small changes in peak positions were observed for the single site mutations, the differences were localized to the residues in the structure that were in close proximity to the mutation. More significant changes were observed with the δ-helix-2 (δ94–105) mutant (Fig. 3). Thus, small conformational changes in the area surrounding the deletion cannot be excluded for the δ-helix-2 mutant, although the overall β-sandwich fold of the domain is certainly maintained. An overlay of 3D 15N-edited NOESY for the wild-type and several mutants proteins further confirmed that the mutant proteins were correctly folded (data not shown).

Figure 3.

1H–15N HSQC spectra of selected XRCC1-NTD1–157 (X157) mutants at 25°C. The spectra of XRCC1-NTD1–183 (X183) and X157 are shown on the top two panels. The two spectra are identical for the folded domain, residues 3–151, and the differences come from the unstructured C-terminal tail, which is 26 residues longer in X183. The spectra of the mutant proteins are very similar to that of X157, except for residues around the site of mutation. The differences are more significant in the δHelix2 mutant (bottom left panel), including doubling of peaks, indicating possible effects on conformation. The positions of deleted/mutated residues in the wild-type spectra are marked with Xs.

Binding of XRCC1-NTD mutants to the β-Pol 22 kDa palm-thumb domain

The binding affinities of the XRCC1-NTD mutant proteins for β-Pol 22kDa domain were studied by gel filtration HPLC in the absence of DNA (Table 2). Binding for the mutant proteins was classified as either the same as wild-type, weaker than wild-type, or absent. For a solution of wild-type XRCC1-NTD and β-Pol 22 kDa domain at concentrations of 200 µM or higher, the two proteins migrated as a single chromatographic peak with an apparent molecular mass of 40 kDa. At lower concentrations a single chromatographic peak was similarly observed, but the average molecular mass was found to decrease as the concentration of the two proteins was decreased. The KD (∼0.3 µM) for complex formation was determined by measuring the apparent molecular mass at equimolar concentrations of 200, 80, 20 and 5 µM and fitting the observed average molecular mass versus concentration curve as previously described (22). The KD of ∼0.3 µM for wild-type XRCC1-NTD binding to the β-Pol 22 kDa domain was very similar to that determined for the XRCC1-NTD–β-Pol 31 kDa domain and XRCC1-NTD–β-Pol complexes (∼0.3 to 0.5 µM).

Table 2. Gel filtration HPLC analysis of complex formation of the XRCC1-NTD and its mutants with the β-Pol 22 kDa domain (β-Pol 22K).

| Apparent molecular massa | Apparent molecular massb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Pol 22K | X157 | Complex | β-Pol 22K | X157 | Complex | |

| Wild-type X157 and non-defective mutants | –c | – | 38 kDa | – | – | 40 kDad |

| Binding defective X157 mutants | 26 kDae | 16 kDaf | – | 26 kDa | 16 kDa | – |

aMolecular mass calculated from the chromatographic migration rate at X157 and β-Pol 22 kDa domain concentrations of 20 µM.

bMolecular mass calculated from the chromatographic migration rate at X157 and β-Pol 22 kDa domain concentrations of 200 µM.

cFor complexes, chromatographic peaks corresponding to the free species were not observed.

dFor the wild-type X157 and for the mutant proteins that did not affect binding, the apparent molecular weight of the complex was 40 kDa at concentrations ≥200 µM. For the E98A mutant, the apparent molecular weight of the complex was 40 kDa at concentrations ≥50 µM.

eThe apparent molecular weight of β-Pol 22K at all concentrations tested was 26 kDa.

fThe apparent molecular weight of wild-type X157 and all mutant proteins at all concentrations tested was 16 kDa, except for δHelix2, which migrated as 15 kDa.

The fitted dissociation constants were similarly determined for the E98A and R109S mutants. Mutant proteins that gave molecular weights for the complex at 20 and 200 µM that were identical to the wild-type XRCC1-NTD (40 kDa at 200 µM; 20 and 38 kDa at 20 µM) were estimated to have a wild-type KD. Those mutant proteins that yielded separate migrating chromatographic peaks at 16 kDa for the XRCC1-NTD and 26 kDa for the β-Pol 22 kDa domain at the 20 and 200 µM concentrations were assessed as having no detectable interaction. On adding the β-Pol 22 kDa domain (200 µM) to the F67A, E69K, E69K/K129E, V86R, or δ-helix-2 XRCC1-NTD mutants (200 µM), separate chromatographic peaks were observed that yielded molecular masses of 15.5 ± 0.5 kDa and 26 kDa ± 0.5 kDa for each of these XRCC1-NTD mutants and the β-Pol 22 kDa domain, respectively. These results were indicative of a defect in XRCC1 mutant binding to the β-Pol 22 kDa domain. For the R109S XRCC1-NTD mutant, a reduction in affinity (KD = 9 µM) for the β-Pol 22 kDa domain was observed. The Y136A mutant showed a weak interaction with the β-Pol 22 kDa domain at 200 µM. The low binding affinity (KD > 200 µM) of Y136A to the β-Pol 22 kDa domain could not be precisely determined. Interestingly, in comparison to the wild-type XRCC1-NTD, the E98A mutant showed an approximate four-fold higher affinity binding (KD ∼0.07 µM) to the β-Pol 22 kDa. The E98K mutant did not show this effect.

Binding of XRCC1-NTD mutants to the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex

The gel mobility shift assay was used to study the formation of the XRCC1-NTD–β-Pol–gapped DNA ternary complex using the wild-type XRCC1-NTD and its mutants. XRCC1-NTD was added at concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, 1.0 and 10 µM to the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex (Fig. 4). A 39mer template strand, an 18mer upstream primer, and a 5′-phosphorylated 20mer downstream primer were used to form the gapped DNA. The wild-type XRCC1-NTD showed full binding to the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex at 10 µM and half maximal binding between 0.1 and 1 µM (Fig. 4). The F67A and Y136A XRCC1-NTD mutants displayed little or no binding to the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex nor did E69K and V86R XRCC1-NTD mutants (data not shown). A slight shift or streaking toward a slower migration species was observed at the highest concentration of 10 µM for these mutant proteins. Binding of R109S was at least 10-fold weaker than that of the wild-type XRCC1-NTD (Fig. 4A). The E69K/K129E and δ-helix-2 mutants showed no binding even at 10 µM (Fig. 4B). R31A/K32A/R34A appeared to bind the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex more tightly than wild-type XRCC1-NTD (Fig. 4C) with a complete supershift observed at a concentration of 1 µM. The R31A/K32A/R34A mutant was found to bind the β-Pol 22 kDa domain in the absence of DNA with wild-type affinity (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The binding of XRCC1 to β-Pol, DNA ligase III, PARP, and PNK are important in the formation of DNA repair complexes that are utilized during BER. In this study, site-directed mutagenesis has been used to characterize amino acid residues at the surface of the 3D structure of the XRCC1 protein that directly contribute to protein–protein interaction with β-Pol. Deletion of the short α2 helix revealed the importance of this structural motif in β-Pol binding. The blue regions of the ribbon representation of the backbone of the XRCC1-NTD (Fig. 1A) illustrate residues previously mapped in the NMR experiment in which binding effects induced by the β-Pol 22 kDa domain were obtained. Since the NMR effects can be induced either by a direct contact with the β-Pol protein or by adjacent through-space interactions resulting from a direct contact (indirect effects), the amino acid residues of the XRCC1-NTD that directly contributed to β-Pol binding were not known. The energetic contributions of a subset of these previously mapped residues to β-Pol binding have now been elucidated.

Mutations that included F67A (βD), E69K (βD), V86R (βE) on the five-stranded β-sheet (Fig. 1C) abolished binding of XRCC1-NTD to β-Pol (Table 1). Mutations that included V117R in α3 and K129E in βG, which were in regions adjacent to the βD and βE strands, did not affect β-Pol binding affinity. Deletion of the α2 helix abolished β-Pol binding, whereas point mutations in α2 that included E98A, E98K and N104A did not affect β-Pol binding. The α2 helix is contiguous with the surface formed by the βD and βE strands and protrudes from the domain. In each case, the mutant proteins were determined to be folded similarly to the wild-type domain at the temperature utilized for binding. However, several of the mutant proteins were found to be temperature sensitive with respect to expression and solubility. Y136 is adjacent to α2 with the Y136 ring partially buried and packed against the helix. The Y136A mutation retained a native XRCC1-NTD fold but abolished β-Pol binding possibly through altering the position of the α2 helix structure. Thus, the βD and βE surface of the five-stranded β-sheet and the adjacent protruding α2 helix form a structural template for interaction with the β-Pol (Fig. 1C). The mutational study has allowed a revision of a previous mechanism of interaction (6). In this revised model, the βD and βE residues F67, E69, and V86 contact the thumb loop of β-Pol and α2 buries itself within three adjacent loops in the palm and thumb (Fig. 1C).

Mutations (H19A, K32A, R31A/K32A/R34A and F142A) at or near a positive charge patch within a shelf region adjacent to the α2 helix and remote from the βD and βE strands had no effect on β-Pol binding. A subset of the residues in this region, including F142, were affected by β-Pol binding in the previous NMR CSM experiment (6). Nevertheless, mutational analysis indicates that this segment does not significantly contribute to β-Pol binding. Previously, we had shown that the β-Pol thumb subdomain was primarily responsible for interaction with the XRCC1-NTD. β-Pol palm-thumb subdomain contact with the βD, βE, and α2 of the XRCC1-NTD as shown in Figure 1C could result in close spatial proximity of the β-Pol palm loop (201–206) but not direct contact with F142. Thus, loop segments in the palm subdomain may be in contact with residues that include α2 and Y136 adjacent to F142, allowing F142 to receive indirect effects in the previous NMR experiment.

In the formation of a β-Pol–gapped DNA–XRCC1-NTD ternary complex, two approximately orthogonal positively charged patches on the XRCC1-NTD were previously found to be optimal for contact with gapped DNA containing a 90° bend (6). The current mechanism of interaction also supports this conclusion. The mutational analysis indicates that the interaction of XRCC1-NTD in the ternary complex with β-Pol and DNA is primarily determined by the energetics of the XRCC1-NTD–β-Pol contacts. The half-binding affinity for the XRCC1-NTD to the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex was highly similar to the KD for interaction with the β-Pol 22 kDa domain.

E69 and K129 form a charge pair conserved among XRCC1 homologs. Charged residues in and around an exposed hydrophobic surface are likely to contribute to the structural stability of the protein by preventing aggregation. E69 is inside the β-Pol binding region and an E69K mutation as described above abolished binding. K129 in the XRCC1-NTD is at the border of the NMR mapped β-Pol binding surface and the K129E mutation had no effect on β-Pol binding. E69 may form a charge pair with a positively charged residue within the thumb of β-Pol, since maintenance of the E69/K129 charge pair is not required for binding. The solubility and possibly folding of the K129E mutant was severely decreased on expression at any temperature. Introduction of a compensating mutation, E69K/K129E, thus reversing the charges, resulted in a partially restored solubility compared to the K129E mutant. Thus, the conserved charge pair E69/K129 is important for solubility, and possibly folding, and at the same time E69 contributes to β-Pol binding specificity.

The E98K mutant corresponds to the E102K mutation found in a hamster cell line EM-C12. The E102K mutation resulted in no detectable XRCC1 and decreased DNA ligase III activity in this cell line (3). For the corresponding E98K XRCC1-NTD mutant, soluble protein could only be obtained on expression at 20°C. The purified E98K XRCC1-NTD mutant precipitated above 20°C consistent with the temperature sensitive expression of soluble protein. The E98K mutant was found to bind β-Pol with an affinity that was indistinguishable from the XRCC1-NTD at room temperature. Thus, the phenotype of the EM-C12 mutation in the CHO cell line may result from loss in soluble XRCC1 expression. The E98A mutant showed a lesser degree of temperature sensitivity with respect to expression of soluble protein. The effect of the E98K mutation is perplexing since E98 does not form a charge pair with another residue (6) and the E98K mutation is unlikely to affect severely the folding of the core of XRCC1-NTD. Possibly, the presence of negative charge is important in preventing aggregation via this exposed helix or through the hydrophobic surface of the five-stranded β-sheet.

The binding of the XRCC1-NTD to the thumb and palm subdomains of β-Pol in the β-Pol–gapped DNA complex results in the formation of a tight complex that encompasses β-strands βD and βE and the α2 helix (Fig. 1C). In this complex, much of the DNA surrounding the strand break is sandwiched between the two proteins. The XRCC1-NTD can contact the 3′-upstream primer and the downstream region of the template simultaneously with protein–protein contacts with the thumb-palm, thereby closing off the exposed DNA surface from solvent, other damaging agents, and other proteins. Surrounding the break in this manner could protect the DNA from cleavage on the opposite strand and thereby prevent potentially lethal double-strand breaks. The significant contributions to binding by several residues, as determined by the mutational results, provide important information, which is not obtainable from a structure of the complex alone. Independent results indicate that mutations in the thumb loop of β-Pol, which include a triple Arg mutant and a multiple residue deletion mutant, have also been shown to abolish XRCC1-NTD–β-Pol 22 kDa domain interaction (24). Presumably, the residues on βD/βE strands of the XRCC1-NTD in conjunction with the interaction of the α2 helix could induce a singular conformational form of the thumb (possibly the closed form as seen here) in β-Pol, and in this manner affect catalysis. Importantly, although no mutations within these regions of the XRCC1 protein have yet been reported in humans, these XRCC1 mutants that affect β-Pol binding and the temperature stability may be of significance in discerning effects of possible genetic polymorphisms. These mutant proteins can also be introduced into XRCC1-deficient cell lines and used to probe the in vivo functions of XRCC1. In summary, having established the direct contacts of interaction between XRCC1-NTD and β-Pol provides a framework for the structural basis of the function of XRCC1 in DNA BER.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Grants ES09847 and GM52738 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thompson L.H., Brookman,K.W., Jones,N.J., Allen,S.A. and Carrano,A.V. (1990) Molecular cloning of the human XRCC1 gene, which corrects defective DNA strand break repair and sister chromatid exchange. Mol. Cell. Biol., 10, 6160–6171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brookman K.W., Tebbs,R.S., Allen,S.A., Tucker,J.D., Swiger,R.R., Lamerdin,J.E., Carrano,A.V. and Thompson,L.H. (1994) Isolation and characterization of mouse Xrcc-1, a DNA repair gene affecting ligation. Genomics, 22, 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen M.R., Zdzienicka,M.Z., Mohrenweiser,H., Thompson,L.H. and Thelen,M.P. (1998) Mutations in hamster single-strand break repair gene XRCC1 causing defective DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 1032–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor R.M., Moore,D.J., Whitehouse,J., Johnson,P. and Caldecott,K.W. (2000) A cell cycle-specific requirement for the XRCC1 BRCT II domain during mammalian DNA strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 735–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson L.H. and West,M.G. (2000) XRCC1 keeps DNA from getting stranded. Mutat. Res., 459, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marintchev A., Mullen,M.A., Maciejewski,M.W., Pan,B., Gryk,M. and Mullen,G.P. (1999) Solution structure of the single-strand break repair protein XRCC1 N-terminal domain. Nature Struct. Biol., 6, 884–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tebbs R.S., Flannery,M.L., Meneses,J.J., Hartmann,A., Tucker,J.D., Thompson,L.H., Cleaver,J.E. and Pedersen,R.A. (1999) Requirement for the Xrcc1 DNA base excision repair gene during early mouse development. Dev. Biol., 208, 513–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldecott K.W., Tucker,J.D., Stanker,L.H. and Thompson,L.H. (1995) Characterization of the XRCC1-DNA ligase III complex in vitro and its absence from mutant hamster cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 4836–4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nash R.A., Caldecott,K.W., Barnes,D.E. and Lindahl,T. (1997) XRCC1 protein interacts with one of two distinct forms of DNA ligase III. Biochemistry, 36, 5207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caldecott K.W., McKeown,C.K., Tucker,J.D., Ljungquist,S. and Thompson,L.H. (1994) An interaction between the mammalian DNA repair protein XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamane K., Katayama,E. and Tsuruo,T. (2000) The BRCT regions of tumor suppressor BRCA1 and of XRCC1 show DNA end binding activity with a multimerizing feature. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 279, 678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldecott K.W., Aoufouchi,S., Johnson,P. and Shall,S. (1996) XRCC1 polypeptide interacts with DNA polymerase β and possibly poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase and DNA ligase III is a novel molecular ‘nick-sensor’ in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 4387–4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masson M., Niedergang,C., Schreiber,V., Muller,S., Ménissier-de Murcia,J. and de Murcia,G. (1998) XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 3563–3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dantzer F., de La Rubia,G., Ménissier-De Murcia,J., Hostomsky,Z., de Murcia,G. and Schreiber,V. (2000) Base excision repair is impaired in mammalian cells lacking poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Biochemistry, 39, 7559–7569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitehouse C.J., Taylor,R.M., Thistlethwaite,A., Zhang,H., Karimi-Busheri,F., Lasko,D.D., Weinfeld,M. and Caldecott,K.W. (2001) XRCC1 stimulates human polynucleotide kinase activity at damaged DNA termini and accelerates DNA single-strand break repair. Cell, 104, 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson S.H. (1998) Mammalian base excision repair and DNA polymerase β. Mutat. Res., 407, 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl T. and Wood,R.D. (1999) Quality control by DNA repair. Science, 286, 1897–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson S.H. and Kunkel,T.A. (2000) Passing the baton in base excision repair. Nature Struct. Biol., 7, 176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singhal R.K., Prasad,R. and Wilson,S.H. (1995) DNA polymerase β conducts the gap-filling step in uracil-initiated base excision repair in a bovine testis nuclear extract. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto Y. and Kim,K. (1995) Excision of deoxyribose phosphate residues by DNA polymerase β during DNA repair. Science, 269, 699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singhal R.K. and Wilson,S.H. (1993) Short gap-filling synthesis by DNA polymerase β is processive. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 15906–15911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marintchev A., Robertson,A., Dimitriadis,E.K., Prasad,R., Wilson,S.H. and Mullen,G.P. (2000) Domain specific interaction in the XRCC1-DNA polymerase β complex. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2049–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartels C., Xia,T.H., Billeter,M., Guntert,P. and Wüthrich,K. (1995) The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral-analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR, 6, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gryk M.R., Marintchev,A., Maciejewski,M.W., Robertson,A., Wilson,S.H. and Mullen,G.P. (2002) Mapping of the interaction interface of DNA polymerase β with XRCC1. Structure, 10, 1709–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koradi R., Billeter,M. and Wüthrich,K. (1996) MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph., 14, 51–55, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]