Abstract

Genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in large populations presents a great challenge, especially if the SNPs are embedded in GC-rich regions, such as the codon 112 SNP in the human apolipoprotein E (apoE). In the present study, we have used immobilized locked nucleic acid (LNA) capture probes combined with LNA-enhancer oligonucleotides to obtain efficient and specific interrogation of SNPs in the apoE codons 112 and 158, respectively. The results demonstrate the usefulness of LNA oligonucleotide capture probes combined with LNA enhancers in mismatch discrimination. The assay was applied to a panel of patient samples with simultaneous genotyping of the patients by DNA sequencing. The apoE genotyping assays for the codons 112 and 158 SNPs resulted in unambiguous results for all patient samples, concurring with those obtained by DNA sequencing.

INTRODUCTION

Recently, there has been considerable interest in developing a method for genotyping of the apolipoprotein E (apoE) in diagnostic screening. Single base alterations within codons 112 and 158 of the apoE gene account for three common alleles (ε2, ε3 and ε4), and the resulting six genotypes of the ApoE protein arise from the expression of any two of the three alleles (1). The apoE genotypes play a key role in the diagnosis of type III hyperlipidemia (2) and have also shown to be an important risk factor in the development of Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular diseases (3,4).

The apoE codon 112 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is located in a highly GC-rich region (2). Genotyping of SNPs embedded in GC-rich regions is often difficult because of the small difference between the melting temperatures of the perfectly matched and the mismatched targets. Furthermore, polymorphic GC-rich repetitive sequences may be non-accessible to hybridization with complementary oligonucleotide capture probes due to their involvement in secondary structure formation via intermolecular Watson– Crick base-pairing (5). Finally, SNP detection in double-stranded PCR amplicons can be complicated by the presence of a complementary strand, which can act as a competitor to the SNP detection probe (6).

The common ApoE polymorphisms have previously been determined by isoelectric focusing of the proteins (7,8), and more recently by Southern or dot blots hybridized with allele-specific oligonucleotide probes or by restriction fragment length polymorphism (9–11). Utilizing the PCR technique for the apoE genotyping has also allowed other methods to be developed. Among these are amplification refractory mutation system (12), real-time PCR (6), oligonucleotide ligation assay (13), primer extension (14), heteroduplex analysis (15), denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (16) and single-strand conformational polymorphism (17). A common feature for the aforementioned methods is that they are generally expensive, time-consuming and difficult to automate due to the requirement of enzymatic digestion and gel electrophoresis. Thus, high-throughput screening of the apoE polymorphisms in human populations calls for robust, reliable and cost-effective methods with optimized performance in genotyping applications. Here, we describe a novel method for apoE genotyping based on the hybridization of PCR amplicons to allele-specific locked nucleic acid (LNA) capture probes in the presence of a LNA-enhancer oligonucleotide, followed by detection of the hybrids using an ELISA-like technique (18,19). The LNA capture probes are attached to microtiter wells by photochemical immobilization using an anthraquinone (AQ) moiety in the LNA capture oligonucleotides (20). The genomic DNA for a selected test panel of patient samples was characterized using both the apoE microtiter plate assay and DNA sequencing. The genotypes obtained with the LNA capture method were in full agreement with those obtained by sequencing of the DNA samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immobilization of LNA capture probes

The capture probes (Table 1) were photo-immobilized to the microtiter wells using an AQ moiety as described by Koch et al. (20). After coupling, the plates were treated according to Ørum et al. (18).

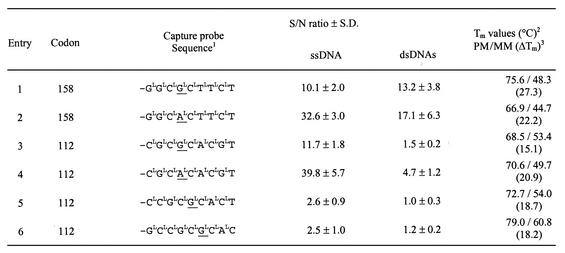

Table 1. Optimization of capture probes and thermostability of the LNA capture probe sequences against the complementary DNA targets.

1 L, 2′-O,4′-C-methylene-d-ribofuranosyl nucleotides (LNA); CL, 5-methyl-CL. The SNP position is underlined

21.0 µM of each of the two complementary strands was used. The complementary DNA sequences were either perfectly matched or contained a single nucleotide mismatch opposite to the underlined nucleotide.

3The difference in duplex melting temperatures (ΔTm) between perfectly matched (PM) and mismatched (MM) ssDNA targets.

Determination of the melting temperatures

Determination of the melting curves was performed without the AQ and the DNA linker moieties. The melting temperatures of the LNA/DNA and the corresponding DNA/DNA duplexes were determined as described by Wahlestedt et al. (21) using 1.0 µM concentrations of the two complementary oligonucleotides in a Tm buffer (10 mmol/l sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 100 mmol/l NaCl, 0.1 mmol/l EDTA). The salt concentration in the Tm buffer corresponds to that of the hybridization buffer in the apoE microtiter plate assay.

In vitro amplification of the apoE PCR products

Two PCR amplicons encompassing either the apoE codon 112 or 158 were generated from genomic DNA (extracted from 5 ml of EDTA-anticoagulated blood using a Roche DNA Isolation reagent set according to the manufacturer’s instructions) either with the codon 112 forward primer, 5′-biotin-GGCGCGGACATGGAGGAC-3′, and the codon 112 reverse primer, 5′-TGCACCTCGCCGCGGTAC-3′, resulting in a 58 bp amplicon, or the codon 158 forward primer, 5′-biotin-CGGCTCCTCCGCGATGCC-3′, and the codon 158 reverse primer, 5′-CCCGGCCTGGTACACTGC-3′, resulting in a 57 bp amplicon. PCRs (50 µl) were prepared by mixing 15 mmol/l Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 50 mmol/l KCl (GeneAmp Gold buffer, PE Biosystems), 2.5 mmol/l MgCl2, 200 µmol/l of each dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 1 µmol/l forward primer, 1 µmol/l reverse primer; 1.25 U (0.25 µl of a 5 U/µl) AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (PE Biosystems) and 100 ng of genomic DNA as template. After an initial 15 min denaturation step at 95°C, 30 cycles of PCR were carried out (40 s at 95°C, 40 s at 65°C and 40 s at 72°C), followed by extension at 72°C for 10 min. Purification of the PCR amplicons was not necessary.

Genotyping of the apoE SNPs from clinical samples

The microtiter plate assay was performed by mixing 20 µl of the PCR amplicon or 0.1 µmol/l synthetic 50mers DNA oligonucleotides encompassing either the codon 112 SNP or the codon 158 SNP with 20 µl of denaturation buffer (125 mmol/l NaOH, 8 mmol/l EDTA, 0.2 g/l phenol red) followed by incubation for 5 min at room temperature. After the addition of 200 µl of hybridization buffer (50 mmol/l sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 0.1 ml/100 ml Tween-20) and the different LNA/DNA-enhancer oligonucleotides for the codon 112, the hybridization mixture was transferred to the coated wells (100 µl/well) containing capture probes for the apoE codon 112 or 158 SNPs and hybridized for 30 min at 37°C. The wells were subsequently washed three times in washing buffer [300 µl/well; 0.5× SSC buffer (75 mmol/l NaCl, 7.5 mmol/l sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 0.1 ml/100 ml Tween-20] followed by the addition of 100 µl of conjugate solution [1 mg/l horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin (Pierce) diluted in the washing buffer] per well and incubation for 15 min at 37°C. Finally, the wells were washed six times with washing buffer (300 µl/well) and 100 µl of a chromogenic substrate was added per well [3,3′,5,5′–tetramethylbenzidine (TMB one) or ortho- phenylenediamine (OPD); both from KemEnTec]. The microtiter plate was then incubated in the dark for 10–15 min at room temperature followed by the addition of 100 µl/well of 0.5 mol/l H2SO4 to stop the reaction. The absorbance was read at λ = 450 nm (TMB one) or at λ = 492 nm (OPD) using an Elisa reader (Wallac Victor2 for the TMB one substrate and SLT spectra Elisa reader for the OPD substrate).

RESULTS

We have previously described the use of LNA capture probes in SNP genotyping assays for Leiden factor V (18) and apolipoprotein B (19). In our first attempt to develop an apoE genotyping assay for the common single base alterations within the codons 112 (TGC→CGC) and 158 (CGC→TGC) (2), we designed the LNA capture probes as shown in Table 1. The capture probes contained an AQ moiety at the 5′ end, which made it possible to covalently link the capture probes to the polymer surface of microtiter wells by soft UV-light illumination (20). For optimal hybridization, a 15mer DNA linker separated the AQ moiety from the sequence-specific capture part (18). The capture part consisted of eight LNA nucleotides and one DNA nucleotide complementary to the sense strand of the apoE codon 112 or 158 SNPs.

The specificity of the LNA genotyping assay was first assessed with synthetic single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) targets, thus mimicking the sense strand encompassing either the codon 112 or 158 SNPs. The double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) targets were generated using PCR amplification. The results for both ssDNA as well as dsDNA targets are presented in Table 1 as the signal from the perfectly matched target (S) relative to the background signal (N) obtained with the single nucleotide mismatched target. The apoE codon 158 capture probes (entries 1 and 2) were able to hybridize specifically to ssDNA and dsDNA targets, respectively. In both cases the hybridization signal from the perfectly matched targets was more than 10 times higher than that from the single nucleotide mismatched targets. The difference in duplex melting temperatures between perfectly matched and mismatched ssDNA targets for the codon 158 capture probes also inferred that optimal conditions for specific hybridization-based genotyping could be identified (Table 1).

The apoE codon 112 SNP is embedded in a CG-rich region as opposed to the codon 158 SNP. Application of the LNA genotyping assay to the codon 112 SNP resulted in low signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios for the dsDNA targets, although reasonable values were obtained for the ssDNA targets. The S/N ratio for the capture probes genotyping the apoE codon 112 CGC (entry 3) and codon 112 TGC (entry 4) using ssDNA targets were 12.9 and 33.6, respectively. To prevent unspecific hybridization, the DNA linker moiety in the LNA capture probes was changed to a 15mer non-base linker. However, when the dsDNA targets were applied to the capture probes both the hybridization signals and the S/N ratios were still unsatisfactorily low. Further oligonucleotide designs for the codon 112 CGC capture probe (entries 5 and 6) were tested in hybridizations to optimize the S/N ratio, but none of these performed better than the capture probe entry 3 (Table 1). Although the difference in duplex melting temperatures between perfectly matched and mismatched ssDNA targets for the codon 112 capture probes exceeds 15°C (Table 1), mismatch discrimination could be seriously hampered by competition from the complementary non-target strand (6). Here, we show that introduction of LNA-enhancer oligonucleotides in combination with the codon 112 capture probes dramatically increased the specific capture efficiency.

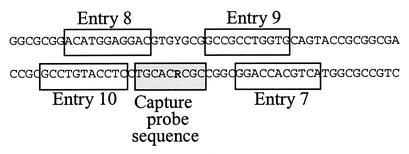

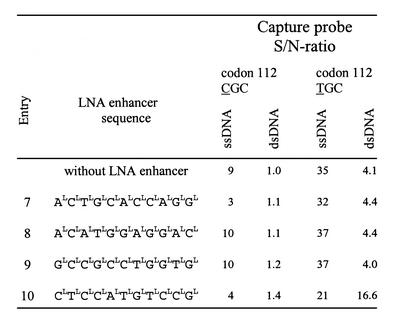

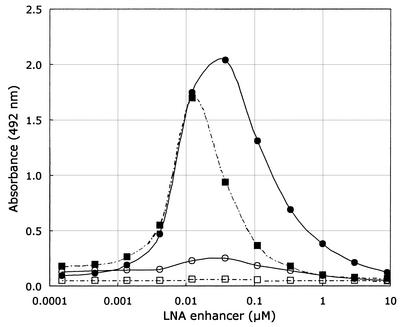

To improve hybridization between the capture probe and target it has previously been shown that DNA oligonucleotides can be used as enhancers to promote specific hybridization (22,23). Thus, we designed a set of LNA-enhancer oligonucleotides, respectively, in the proximity of the apoE codon 112 capture probes target (Fig. 1). The aim was to increase the exposure of the apoE codon 112 SNP sense strand to its respective LNA capture probe thereby enhancing the absolute signals and the S/N ratios in the apoE assay. Both the LNA and DNA enhancers were included in the hybridization mixture and allowed simultaneous hybridization of the capture probe to the DNA target. As seen in Table 2, the effect of the entries 7, 8 and 9 on the S/N ratios for both ssDNA and dsDNA targets was minimal. Although entry 10 had a lowering effect on the S/N ratio for the ssDNA targets, it significantly increased the absolute values with dsDNA targets (data not shown) and improved the S/N ratio for the codon 112 TGC capture probe (Table 2). A dose response curve for the effect of the LNA enhancers (entries 7–10) was performed to obtain optimal conditions for the apoE genotyping assay. Figure 2 shows a titration of the LNA enhancer entry 10 concentration ranging from 0 to 0.1 µM for the two capture probes challenged against the apoE codon 112 SNP. The optimal effect of the LNA enhancer was obtained at a final concentration of 0.02 µM in the hybridization mixture. At the optimal LNA-enhancer concentration, the S/N ratios for the codons 112 TGC and CGC were 27.8 and 7.6, respectively. For comparison, we determined the S/N ratios using the corresponding DNA oligonucleotide. While a S/N ratio of 15.4 was observed for the codon TGC at the concentration of 0.1 µM, there was no apparent enhancing effect on the S/N ratio for the codon CGC (Table 3). Therefore, all subsequent experiments were carried out using LNA-enhancer oligonucleotides.

Figure 1.

The position of the apoE codon 112 capture probes and the LNA-enhancer oligonucleotides from Table 2.

Table 2. Design of the LNA-enhancer oligonucleotides.

Figure 2.

A concentration titration of the LNA enhancer (entry 10). The assay was applied on double-stranded PCR amplicons encompassing codon 112 SNP: perfectly matched amplicon codon 112 TGC towards the LNA capture probe codon 112 TGC (closed circles), single mismatched amplicon codon 112 TGC towards the LNA capture probe codon 112 CGC (open circles), perfectly matched amplicon codon 112 CGC towards the LNA capture probe 112 CGC (closed squares), and single mismatched amplicon codon 112 CGC towards the LNA capture probe codon 112 TGC (open squares).

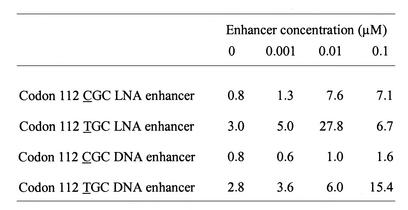

Table 3. The S/N ratio for LNA-enhancer entry 10 and the sequence identical DNA enhancer at various concentrations.

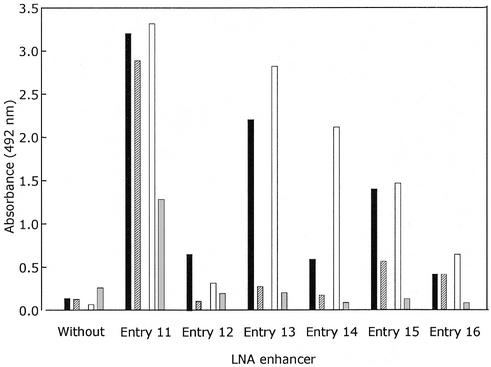

Further studies were made to fine-tune the enhancer properties of the LNA-enhancer entry 10. The LNA enhancer was designed in 22 different versions by moving the window of the probe one nucleotide at a time and/or by shortening the LNA enhancer. Entries 11–16 in Table 4 show a selection of the LNA enhancers. None of the tiled 11mer LNA enhancers (entries 11 and 12) improved the S/N ratios for either codon 112 CGC or codon 112 TGC capture probes. When the original LNA enhancer (entry 10) was shortened at either the 3′ or 5′ end (entries 13 and 14) by 1 nt, a significant improvement of the S/N ratios and the absolute values for both capture probes was observed. Further shortening of the enhancer by 2 or 3 nt at the 3′ end (entries 15 and 16) did not result in additional improvement. Entry 13, LNA 5′-CLTLCLCLALTLGLTLCLCL-3′ (Fig. 3), represents the most powerful LNA enhancer for both the codon 112 and 158 found by this scanning procedure. The optimal final concentration for this LNA enhancer (entry 13) was also found to be 0.02 µM in the hybridization mixture.

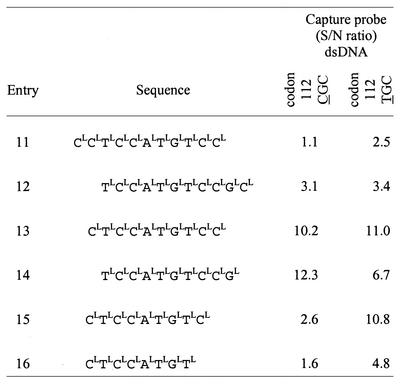

Table 4. Design of improved LNA-enhancer oligonucleotides.

Figure 3.

Optimization of the LNA-enhancer probes (entry 11–16): perfectly matched amplicon codon 112 TGC towards the capture probe codon 112 TGC (black bars), single mismatched amplicon codon 112 TGC towards the capture probe codon 112 CGC (hatched bars), perfectly matched amplicon codon 112 CGC towards the capture probe codon 112 CGC (open bars), and single mismatched amplicon codon 112 TGC towards the capture probe codon 112 CGC (gray bars).

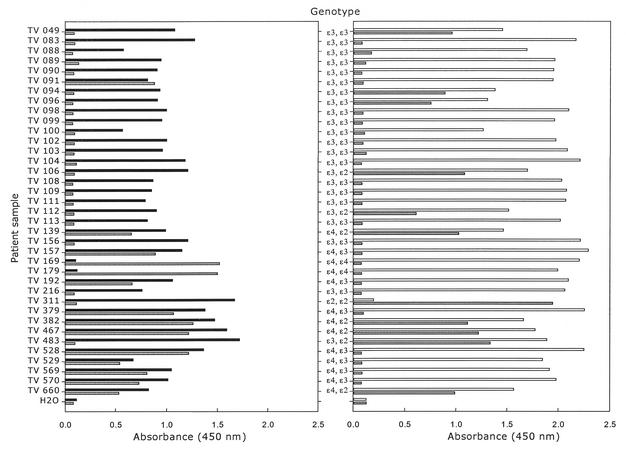

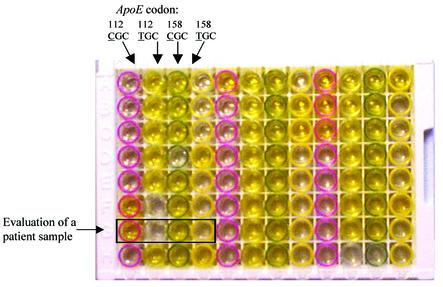

Finally, the apoE LNA genotyping assay was applied to a selected panel of patient samples previously genotyped for the apoE polymorphisms (24) (Fig. 4). Purified genomic DNA from the patients was used as template in the amplification of the apoE PCR products. The apoE genotyping assay resulted in clear, unambiguous results for all patient samples, concurring with the genotypes obtained by DNA sequencing (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Validation of the apoE microtiter plate assay on patient samples. The absorbance values at 450 nm are given on the x-axis, and patient samples and genotypes on the y-axis. Black bars indicate signals from wells containing the codon 112 TGC capture probe. Hatched bars indicate signals from wells containing the codon 112 CGC capture probe. Open bars indicate signals from wells containing the codon 158 CGC capture probe. Finally, gray bars indicate signals from wells containing the codon 158 TGC capture probe.

Figure 5.

An illustration of the microtiter plate for the apoE genotyping assay on patient samples. Codon 112 CGC (purple strip), codon 112 TGC (clear strip), codon 158 CGC (green strip) and codon 158 TGC (yellow strip). The SNP position is underlined.

DISCUSSION

We have established a new genotyping method for the detection of the human apoE codon 112 and 158 SNPs. The LNA capture probes for the apoE codon 158 demonstrated the usefulness of octamer LNA oligonucleotides in SNP genotyping. In contrast to DNA oligonucleotides, the use of LNA oligonucleotide capture probes results in an increased duplex melting temperature with a simultaneous increase in the ΔTm between the perfectly matched and mismatched targets (data not shown). These properties of LNA broaden the interval in which it is possible to find optimal conditions for specific hybridization to a matched target compared with a single mismatched target (25). Similar favorable hybridization properties could be obtained with LNA capture probes for the apoE codon 112 SNP when tested against ssDNA targets. In contrast, the codon 112 capture probes were not able to hybridize specifically to the corresponding dsDNA targets. The duplex melting temperatures for the codon 112 capture probes were comparable to those of the codon 158 capture probes, in line with the hybridization results obtained with ssDNA targets. This suggests that the target strands themselves do not form secondary structures thereby preventing hybridization to the capture probes. As discussed by Bernard et al. (6), genotyping of dsDNA amplicons can be complicated; in particular this is true for GC-rich regions as is the case with the codon 112 in the apoE.

Previous NMR studies of LNA oligonucleotides hybridized to complementary DNA oligonucleotides have shown that conformationally restricted LNA oligonucleotides introduce a more efficient stacking of the nucleobases. In turn, this twists the B-type dsDNA helix structure into an A-type helix structure thereby enhancing hybridization efficiency (26). Furthermore, short DNA oligonucleotides adjacent to each other have been reported to induce a several-fold increase in priming the complementary strand (27,28). Lane et al. (23) have shown that the strongest base-pair stacking interactions between neighboring DNA oligonucleotides occur when the oligonucleotides are situated ‘head-to-tail’ separated by a nick only, and not by a single nucleotide gap. The change in the helix structure when a LNA/DNA hybrid is formed might favor the hybridization to the capture probes by LNA co-axial stacking interactions.

The present study using LNA enhancers implies that LNA oligonucleotides can be designed to enhance the specific recognition of the target in hybridization-based SNP assays together with LNA capture probes. In contrast, the corresponding DNA oligonucleotides were not found to be useful in the apoE genotyping assay. To further extend the use of LNA-enhancer oligonucleotides in hybridization-based assays and to provide general LNA design rules requires additional experiments. Genotyping methods based on DNA target recognition require a high level of sensitivity and specificity in order to discriminate effectively between target sequences differing by one nucleotide only. This has been achieved with the present apoE assay based on the LNA technology, thus demonstrating that LNA oligonucleotides are well suited for SNP detection. However, SNP detection of targets in GC-rich or structured regions may require an additional LNA-enhancer oligonucleotide, as shown here with the apoE codon 112 SNP. Conformational fixation of the sugar moiety in the LNA nucleotide enables the design of short LNA capture probes capable of identifying DNA targets differing by a single nucleotide only. The present work demonstrates that the combined use of the LNA capture probes and enhancer oligonucleotides together with the AQ technology provides a simple, fast and sensitive assay for genotyping of the apoE alleles. The digital read-out of the microtiter plate makes the present apoE genotyping assay well suited for high-throughput screening of the apoE polymorphisms in clinical laboratories at a low cost. Hence, by combining these technologies it should be relatively straightforward to use the assay in high-throughput clinical screening programs or to miniaturize the assay onto a microarray platform.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Marianne Søs Ludvigsen, Kirsten Gerner-Smidt, Dana Tvermoes and Mette Bjørn at Exiqon for expert technical assistance and Jette Nymann and Anne Qvist Rasmussen at the University Hospital of Copenhagen for their skilled technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahley R.W. (1988) Apolipoprotein E: cholesterol transport protein with expanding role in cell biology. Science, 240, 622–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breslow J.L., McPherson,J., Nussbaum,A.L., Williams,H.W., Lofquist-Kahl,F., Karathanasis,S.K. and Zannis,V.I. (1982) Identification and DNA sequence of a human apolipoprotein E cDNA clone. J. Biol. Chem., 257, 14639–14641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corder E.H., Saunders,A.M., Strittmatter,W.J., Schmechel,D.E., Gaskell,P.C., Small,G.W., Roses,A.D., Haines,J.L. and Pericak-Vance,M.A. (1993) Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science, 261, 921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson P.W., Schaefer,E.J., Larson,M.G. and Ordovas,J.M. (1996) Apolipoprotein E alleles and risk of coronary disease. A meta-analysis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 16, 1250–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen H.K. and Southern,E.M. (2000) Minimising the secondary structure of DNA targets by incorporation of a modified deoxynucleoside: implications for nucleic acid analysis by hybridisation. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3904–3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard P.S., Pritham,G.H. and Wittwer,C.T. (1999) Color multiplexing hybridization probes using the apolipoprotein E locus as a model system for genotyping. Anal. Biochem., 273, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warnick G.R., Mayfield,C., Albers,J.J. and Hazzard,W.R. (1979) Gel isoelectric focusing method for specific diagnosis of familial hyperlipoproteinemia type 3. Clin. Chem., 25, 279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kane J.W. and Gowland,E. (1986) A method for the identification of apolipoprotein E isoforms employing chemical precipitation and flat bed isoelectric focusing in agarose. Ann. Clin. Biochem., 23, 509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emi M., Wu,L.L., Robertson,M.A., Myers,R.L., Hegele,R.A., Williams,R.R., White,R. and Lalouel,J.M. (1988) Genotyping and sequence analysis of apolipoprotein E isoforms. Genomics, 3, 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen P.S., Gerdes,L.U., Klausen,I.C., Gregersen,N. and Faergeman,O. (1994) Genotyping compared with protein phenotyping of the common apolipoprotein E polymorphism. Clin. Chim. Acta, 224, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houlston R.S., Wenham,P.R. and Humphries,S.E. (1990) Detection of apolipoprotein E polymorphisms using PCR/ASO probes and Southern transfer: application for routine use. Clin. Chim. Acta, 189, 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenham P.R., Newton,C.R. and Price,W.H. (1991) Analysis of apolipoprotein E genotypes by the amplification refractory mutation system. Clin. Chem., 37, 241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron H., Fung,S., Aydin,A., Bahring,S., Jeschke,E., Luft,F.C. and Schuster,H. (1997) Oligonucleotide ligation assay for detection of apolipoprotein E polymorphisms. Clin. Chem., 43, 1984–1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Syvanen A.C., Aalto-Setala,K., Harju,L., Kontula,K. and Soderlund,H. (1990) A primer-guided nucleotide incorporation assay in the genotyping of apolipoprotein E. Genomics, 8, 684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolla M.K., Wood,N. and Humphries,S.E. (1999) Rapid determination of apolipoprotein E genotype using a heteroduplex generator. J. Lipid Res., 40, 2340–2345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker S., Angelico,M.C., Laffel,L. and Krolewski,A.S. (1993) Application of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis to detect DNA sequence differences encoding apolipoprotein E isoforms. Genomics, 16, 245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai M.Y., Suess,P., Schwichtenberg,K., Eckfeldt,J.H., Yuan,J., Tuchman,M. and Hunninghake,D. (1993) Determination of apolipoprotein E genotypes by single-strand conformational polymorphism. Clin. Chem., 39, 2121–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ørum H., Jakobsen,M.H., Koch,T., Vuust,J. and Borre,M.B. (1999) Detection of the factor V Leiden mutation by direct allele-specific hybridization of PCR amplicons to photoimmobilized locked nucleic acids. Clin. Chem., 45, 1898–1905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsen N., Fenger,M., Bentzen,J., Rasmussen,S., Jakobsen,M., Fenstholt,J. and Skouv,J. (2002) Genotyping of the apolipoprotein B R3500Q mutation using immobilized locked nucleic acid capture probes. Clin. Chem., 48, 657–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch T., Jacobsen,N., Fensholdt,J., Boas,U., Fenger,M. and Jakobsen,M.H. (2000) Photochemical immobilization of anthraquinone conjugated oligonucleotides and PCR amplicons on solid surfaces. Bioconjug. Chem., 11, 474–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahlestedt C., Salmi,P., Good,L., Kela,J., Johnsson,T., Hokfelt,T., Broberger,C., Porreca,F., Lai,J., Ren,K. et al. (2000) Potent and nontoxic antisense oligonucleotides containing locked nucleic acids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5633–5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Meara D., Yun,Z., Sonnerborg,A. and Lundeberg,J. (1998) Cooperative oligonucleotides mediating direct capture of hepatitis C virus RNA from serum. J. Clin. Microbiol., 36, 2454–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane M.J., Paner,T., Kashin,I., Faldasz,B.D., Li,B., Gallo,F.J. and Benight,A.S. (1997) The thermodynamic advantage of DNA oligonucleotide ‘stacking hybridization’ reactions: energetics of a DNA nick. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 611–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poulsen P., Kyvik,K.O., Vaag,A. and Beck-Nielsen,H. (1999) Heritability of type II (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and abnormal glucose tolerance—a population-based twin study. Diabetologia, 42, 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh S.K. and Wengel,J. (1998) Universality of LNA-mediated high-affinity nucleic acid recognition. Chem. Commun., 12, 1247–1248. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen C.B., Singh,S.K., Wengel,J. and Jacobsen,J.P. (1999) The solution structure of a locked nucleic acid (LNA) hybridized to DNA. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 17, 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotler L.E., Zevin-Sonkin,D., Sobolev,I.A., Beskin,A.D. and Ulanovsky,L.E. (1993) DNA sequencing: modular primers assembled from a library of hexamers or pentamers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 4241–4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kieleczawa J., Dunn,J.J. and Studier,F.W. (1992) DNA sequencing by primer walking with strings of contiguous hexamers. Science, 258, 1787–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]