Health and poverty are inextricably intertwined. Being able to breast-feed, attend school, work to grow food, earn a living or feed a family all depend on a baseline level of good health. Yet, when more than a billion people live on less than $1 per day and 2 billion on less than $2 a day, many have little scope to save against future costs of poor health or even to pay for health services today.

Extreme poverty interacts with health in many ways and undermines a whole range of human capabilities, possibilities and opportunities.1 Evidence from all parts of the world support a link between poverty, hunger and poor child health.2 Poor child health and hunger lead to poor school performance and therefore to a later inability to find good work and support the next family. Thus, the downward spiral that maintains poverty continues.

Poverty also leads to increased dangers to health: working environments of poorer people often hold more environmental risks for illness and disability; other environmental factors, such as lack of access to clean water, disproportionately affect poor families. Over 40% of the world's population do not have basic sanitation, and more than 1 billion people still use unsafe sources of drinking water (see the United Nations [UN] Millennium Project, Fast Facts: Faces of Poverty, at www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/MP-PovertyFacts-E.pdf).

People enduring poverty are also usually less educated. They often have less knowledge about activities to promote health and when to access health care; for example, poor women access antenatal services less frequently and suffer poorer birthing outcomes than women with financial resources. These effects extend beyond birth: children born to women with 5 years or more of primary school education have a 40% higher survival rate than those born to women with no education (UN Millennium Project, Fast Facts: Faces of Poverty).

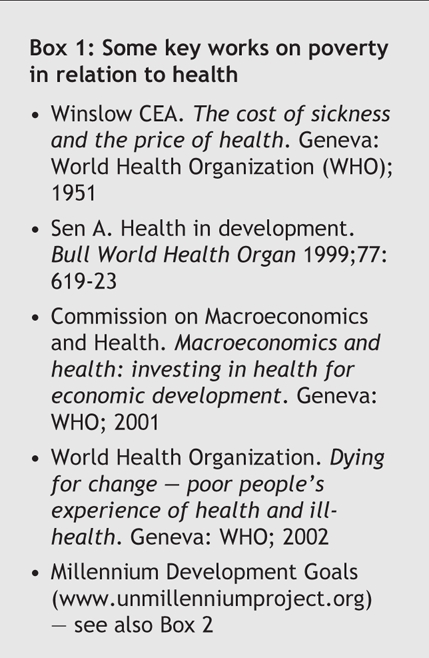

The relation between poverty and health has become a key focus in recent international policy development (Box 1). Development and economic discourse alike acknowledge health as central to poverty reduction and socioeconomic development. The effect of hunger on labour productivity is estimated to reduce the gross domestic product (GDP) by 6%–10% per capita; iron deficiency anemia alone accounts for 2%– 7% of forgone GDP in some developing countries (see the UN Millennium Project's Halving Hunger report, available at www.unmillenniumproject.org/reports/tf_hunger.htm).

Box 1.

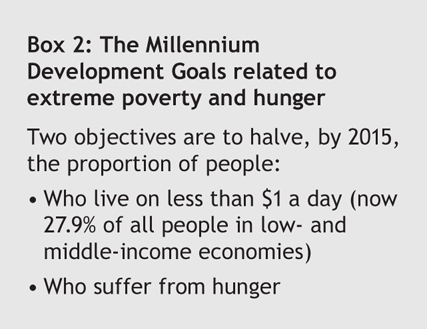

The Millennium Development Goals set by the UN also tackle poverty and hunger (Box 2); however, progress toward these goals has so far been mixed. The global poverty rate has fallen since 1990, with 100 million fewer people living in poverty; nevertheless, the number of extremely poor people in sub-Saharan Africa doubled between 1981 and 2001, to 313 million. Progress in hunger reduction has been slow despite low-cost measures such as breast-feeding and increased availability of improved diets for pregnant and lactating women, nutritional support for sick children, oral rehydration therapy, control of parasitic diseases and treatment of vitamin A deficiency.

Box 2.

Neither do poverty reduction measures alone necessarily reduce health inequalities within countries. Even in richer, developed nations, inequalities in health outcomes are evident; indigenous Australians, for example, have a life expectancy 20 years shorter than that of white Australians, despite its “developed country” status. Recent work within Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries shows that richer patients have greater access than poorer patients to specialist care.3 National data must not obscure troubling health-outcome patterns within countries.

As many people as there are who view health to be a “right” for all, its short-term improvement seems for many to be inescapably dependent on supportive economic policy and health-focused development aimed at breaking the vicious link between poverty and poor health.

Sally Murray Editorial Fellow, CMAJ

Figure.

Photo by: WHO/P. Virot

REFERENCES

- 1.Müller O, Krawinkel M. Malnutrition and health in developing countries [review]. CMAJ 2005;173(3):279-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.McIntyre L, Connor SK, Warren J. Child hunger in Canada: results of the 1994 National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. CMAJ 2000:163(8):961-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Van Doorslaer E, Masseria C, Koolman X; the OECD Health Equity Research Group. Inequalities in access to medical care by income in developed countries. CMAJ 2006;174(2):177-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]