An Ad-hoc Committee* of the Editorial Board was asked by Dr. John Hoey, the former editor in chief of CMAJ to review a series of recent events that he asserted compromised the editorial independence of CMAJ. We have reviewed the events, examined documents, and interviewed selected members of the editorial team to obtain their perspective. We view the episodes as raising serious concern about the integrity of the journal, its reputation, and its viability in the community of top medical journals.

The initial conflict that prompted the formation of the Committee involved a news report about guidelines followed by Canadian pharmacists in dispensing the emergency contraceptive Plan B (oral levonorgestrel).1 Detailed accounts of the controversy surrounding publication of the report were submitted to us for consideration by the journal's senior editors and news staff.2,3

We find fault with the willingness of the editorial team to respond to pressure from the CMA by modifying a report slated for publication in the journal. We also fault them for failing to follow appropriate channels of protest, namely through the Journal Oversight Committee (JOC). We find far more serious fault, however, with the CMA for blatant interference with the publication of a legitimate report.

The documents prepared by the editors outline how CMA, acting through senior management of CMA Holdings, the journal's present owner, violated the journal's editorial independence through its censure of the Plan B article. The editors rejected as both incorrect and spurious the claim that the article did not meet acceptable standards for publication in the journal.

The Committee fully endorses the editors' argument that the objections raised by the CMA obscure the essential facts of the conflict, namely that the CMAJ attempted to publish material that, as it happened, was politically awkward for the CMA, and that the CMA attempted to suppress the publication of that material and, to an important degree, succeeded.

This conflict raises a number of questions concerning the mission of the CMAJ and its editors' degree of autonomy:

• Is news reporting part of the proper scope of the CMAJ?

• Is investigative news reporting a legitimate activity for medical journals in general, and for CMAJ in particular?

• Did the CMAJ news department conduct itself appropriately in preparing the article?

• Whose prerogative is it to determine the scope and content of CMAJ?

• What are the CMAJ owners and stakeholders, the CMA/CMAH, views about the independence of CMAJ's editors in formulating day-to-day content of the journal?

• Is the CMAJ truly independent of orders and pressure from the journal's owners, or is the CMAJ to be subject to political exigencies, including the whim of whoever happens to be in authority positions in CMA and CMAH at the time?

In the following discussion, we comment on the specific case, reflect on the underlying issues, and offer proposals for addressing these issues. We argue that immediate corrective action is needed.

The Plan B article

1. News, not “research.” Contrary to the claims of the CMA that the Plan B article could be construed as a scientific study and was subject to all the requirements of such an investigation, in the opinion of the Committee, the report (both as it was intended to be published and as it eventually appeared) does not meet the definition of “research” as understood in medical science. It is not systematic, is not generalizable, and makes no pretense of statistical analysis. In no way does it fit into a “grey area.” It self-evidently fits within the norms of news investigation, not of scientific research, and its presentation within the news section of the journal makes its identity unambiguous. The CMA's objection that a breach of scientific research ethics (i.e., a failure to obtain approval or informed consent) occurred in the preparation of the story is therefore specious.

2. Responsible journalism. The article as it was intended to be published represented legitimate and ethically responsible journalism. It was newsworthy, relevant and important. It employed standard techniques of investigative reporting, and the desired information — the perspective of individual patients — could not have been obtained by other means.

3. Characteristics of investigative journalism. Daily “beat” reporting presents credible information, largely accepted at face value, from normative, “bureaucratically credible”4 sources. Investigative reporting, by contrast, also weighs testimony from “unauthorized” or unofficial sources, and in so doing may uncover information that is not generally known or draw inferences that conflict with an official view. In the Plan B story, the perspectives of individual women were weighed against the official policy of the Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA) on Plan B dispensing. Their experiences pointed to shortcomings in the CPhA guidelines (e.g., lack of privacy, potential for delays in access to the drug) that were not acknowledged in the official view. And, as often results from “watchdog” reporting, the investigation resulted in prompt constructive action: the privacy commissioners of Ontario and of Manitoba concurred with the concerns raised by the CMAJ news report, and the CPhA (and other provincial pharmacists' associations) have revised their guidelines. We assert that this community response helps to confirm the relevance and social importance of the CMAJ report.

4. A violation of editorial independence. The interference of CMA/CMAH with the Plan B story was a clear and overt infringement of editorial independence. It is a blatant example of editorial interference — the first time that the current editors had ever been instructed to pull a story. Moreover, although the Plan B story was not entirely suppressed, the version that was published on Dec. 6, 2005, was not the story that the journal set out to publish; the pressure exerted on the editors resulted in a “sanitized” version from which the direct testimony of individual women was expunged.

5. Response of CMAJ's editors. The response by the editors, in our view, was inappropriate. Rather than agreeing to modify the text of the article, the editors should not have capitulated to such an inappropriate demand. Faced with this unreasonable demand, the editors should have appealed immediately to the JOC, which, in theory, is responsible for preserving CMAJ's editorial independence.

6. Further incursion on editorial independence. As this report on the Plan B commentary was being finalized, we became aware through a communication of the Canadian Health Coalition that another news story published electronically on Feb. 7, 2006, was subsequently removed from the CMAJ Web site (online Appendix 1, www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/174/7/945). The article was a report on the appointment of the federal Minister of Health by the new Conservative government. It pointed out the health minister's favourable stance toward privatization of health care delivery during his tenure as the Minister of Health for Ontario. On Feb. 22, 2006, a different report on the federal Minister of Health appeared in the original's place (online Appendix 2, www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/174/7/945). Though the revised article contains some of the same phraseology as the original, it is more supportive and less critical of the health minister and seems more beneficial to the CMA. We pose the question as to whether the extensive revision of this article is another instance in which the political interests of the CMA exerted an influence on CMAJ publishing decisions. Some days before the firing of the editor in chief and senior deputy editor, the JOC was informed about a disagreement concerning the original Tony Clement article, but the JOC turned down a request for an emergency meeting. The editors are not willing to comment on how the changes came about; the publisher has also declined comment.

The underlying issues

1. The scope of the journal. The Committee believes that investigative reporting is consistent with the aims and traditions of medical journals. The Lancet is one of the world's leading medical journals and was founded by the reformist Thomas Wakley in 1823 as a vehicle to expose nepotism and other moral deficiencies within medicine and medical education. The inaugural issue of CMAJ in 1911 announced the intent to provide “fresh information, free comment, and sound opinion,”5 the goal being, among other things, to foster improvements in clinical practice. Although investigative reporting was not part of the original activities of the CMAJ (and does not figure prominently in the journal even now) it is consistent with the journal's founding aim of providing a fresh and hence potentially corrective view. The journal has often been critical. (From the journal's second number: “The Ontario Medical Council is under a cloud … its usefulness, as at present constituted, is gone.”6) Moreover, regular “beat” reporting on medical news has been a feature of the journal throughout its history.

Many of the best modern journals, including Lancet, BMJ, Science, Nature, the New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA and Annals of Internal Medicine engage in reporting of various kinds.

2. CMAJ as an instrument of change. Regardless of the founding ambitions of CMAJ, the journal has matured into a publication capable of sharp and influential critique. Through editorials, commentaries, news articles and original research studies the journal's contributors and editors have scrutinized the conduct of agencies, institutions, industry, elected officials, medical professionals and their associations. For example, the journal's criticism of the state of adverse event reporting in Canada,7 and its resolve to monitor and republish FDA physician advisories, led to greater responsiveness on the part of Health Canada, constructive collaboration, and an ongoing column of value to readers (“Health and Drug Alerts”).

CMAJ's investigation into the outbreaks of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in some Canadian hospitals, first released online on June 4, 2004, is a particularly important and telling example of investigative medical reporting in the public interest. The journal's news staff followed an “insider” lead, gathered information, and eventually produced the first public report on this serious and urgent public health problem. The lead to the print version of the story read:

More people have died after contracting a virulent infection that has broken out in hospitals in Montreal and Calgary than were killed by SARS – yet neither public health nor hospital officials warned the public until CMAJ broke the news.8

The results of investigative reporting are bound to be politically or strategically inconvenient for someone. The C. difficile story was unflattering to certain hospitals and the Quebec health minister, and set off a chain of responses that resulted in better surveillance and control of nosocomial C. difficile infection. It is entirely possible that breaking the C. difficile story saved lives. The importance of the news team's work was acknowledged by a nomination of CMAJ for the prestigious Michener Award for meritorious public service in journalism. The journal was congratulated by CMA and CMAH on this success.

Similarly, the Plan B story provoked policy changes of benefit to Canadian patients. However, in this case, the political inconvenience was felt by the CMA, which applied pressure on the journal in response to a complaint from the CPhA, one of the CMA's strategic partners. The C. difficile and Plan B stories share some of the same markers of investigative reporting, yet one was valued by the CMA and the other condemned, apparently related to the association's political priorities.

3. The relationship between CMAJ and CMA. An unsigned editorial from the Feb. 13, 1965, issue of CMAJ reflects on the legacy of the Lancet founder Thomas Wakley's legacy and states:

He whose business it is to edit or write for a public journal is a journalist. By extension, a physician who edits or writes for a medical journal is a medical journalist and is practising medical journalism. When the professional component, the doctor's writing or editing, is harnessed to a complex business organization whose essential object it is to produce a commercially viable product, the result is called medical publishing. Each periodical that deals with medicine should be examined on its own merits because the proportionate influence on the end product of its two principal elements, medicine and commerce, varies widely.9

A later editorial in the same series states:

[W]here the relationship is a true and natural one, the highest interests, welfare and objectives of a medical association and its journal are coincident, coexistent and coterminous.10

This comment was written when CMAJ was distributed weekly to 17 408 members. As its editor notes in the same article, potential competition from other journals was of concern, and being the “official” journal of the country's national medical association was conducive to the journal's survival. Since that time, the number of print subscribers has almost quadrupled. CMAJ is ranked 5th among general medical journals with respect to its impact factor. It is the leading Canadian medical journal, and is now competitive with journals of international standing such as JAMA and BMJ. The expectations of medical journal publishing have also changed. To maintain the prestige it has gained in 95 years of publication, retain the advantage of a markedly higher profile it has acquired during the current editorship both in Canada and abroad, and sustain its credibility and influence in the scientific community and beyond, CMAJ cannot be deemed to be a CMA newsletter; a cat's paw that is under the editorial direction of its custodians, the CMA/CMAH. The loss of its autonomy would be catastrophic for the reputation of the journal. It is likely to become known as an “association rag.”

In fact, the “highest interests” of the CMA and of CMAJ can and should coincide. These interests include the values of medical professionalism that the journal editors proposed in December 2005 for the mandate and terms of reference of CMAJ's JOC, and that are reflected in the Mission Statement approved by the JOC in November 2002. The proposed revision of the Terms of Reference reads, in part, as follows:

The JOC will monitor the quality of the Journal on an ongoing basis by assessing its content and strategic development in light of the values of the medical profession, which include scientific objectivity, respect for patients, health promotion, altruism, truth-telling, leadership and beneficence.

In the opinion of this Committee, news reporting that exposes an abuse of patient privacy or draws attention to undeclared risks faced by elective surgery patients, or draws attention to controversial policies of officials is consistent with these aims.

4. Recurring tensions. The transfer of CMAJ to CMAH in January 2005 was interpreted by some as an attempt to place the journal at arm's length from association politics. However, the editors have not seen a consequent reduction in attempts by CMA to influence CMAJ editorial direction. For example, the Committee has heard from editors that they have been criticized by CMAH for publishing material unflattering to the journal's advertisers. In the past few years, objections have been raised over a number of articles. Such criticism is appropriate, even healthy, unless it results in undue pressure on the editors not to delve into controversial issues. Unfortunately, conflicts arising from the publication of controversial material have led on different occasions to unpleasant confrontations between CMA/CMAH executives and editorial staff. The firing of the editor in chief and the senior deputy editor on Feb. 20, 2006, is being interpreted in the media as related to conflicts surrounding editorial independence and is likely to have an inhibiting effect on the subsequent editorial direction of the journal.

During the editorship of Dr. John Hoey, CMA/CMAH executives have proposed various remedies to recurring tensions. Editors have been asked to give advance warnings about potentially controversial material. The editors have for the most part complied with this request. Editors have told the Committee that they have been asked to consult with CMA on the selection of commentators, and to allow the publisher to read editorials in advance of publication. The editors have not complied with these requests, but have made it clear that the CMA is welcome to submit countervailing letters and articles to the journal in response to published articles.

A strained relationship between the journal and its publisher is not conducive to the responsible reporting of either medical news or science. Responsibility in both scientific and journalistic communication requires that one may honestly report research results or other information without fear of censoring or reprisal of any kind.

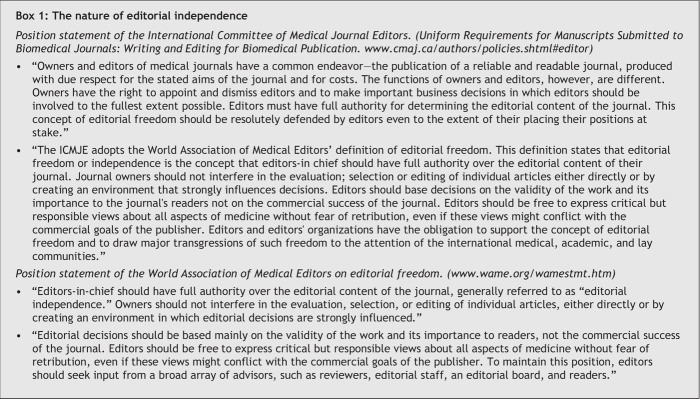

5. Editorial independence: without conditions. The CMA's interference with the Plan B story would not be justifiable even if the story had been substandard. Publishers have the option of dismissing an editor who exhibits a pattern of incompetence, misconduct or fiscal irresponsibility. As long as editors hold their position, however, they must be free to make editorial decisions independently of the ideological, strategic or commercial interests of the publisher. The editor's conduct should be judged against the ideals of the medical profession and against standards of accuracy, precision and fairness. Editorial decisions should not be judged against the particular aims of the CMA. Guidelines on the nature of editorial independence by the respected World Association of Medical Editors and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors are well established (Box 1).

Box 1.

6. The independence of leading journals. Highly respected medical associations accept the editorial independence of their editors as fundamental. The American Medical Association, as one example, steadfastly defends the autonomy of its journal editors through its Journal Oversight Committee that was established after the controversial dismissal of former editor-in-chief George Lundberg. Editors of the New England Journal of Medicine, the world's leading medical journal, have expressed opinions in their journals at odds with the position of their publisher, the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS), and sometimes against the best interests of the journal's advertisers. Several former editors wrote without censure in the New England Journal of Medicine on hot-button topics such as physician-assisted suicide, the breast implant controversy, ethics of medical research in developing countries, the problems of the pharmaceutical industry and the medical use of marijuana. One even advocated for a single-payer health care system in opposition to the official position of the MMS. Rather than restricting the editors, the MMS actively participated in debates about these issues, occasionally in the pages of the journal but more often in articles in the general media. The ability to publish controversial or unpopular opinion is an important measure of the maturity of a journal and of its sponsoring association within the framework of a democratic society.

7. The future of the journal. CMAJ is a substantial, respected and established journal, and has the potential to become a great journal. If CMA/CMAH do not accept the possibility for dissonance between their own strategic objectives and the diverse points of view presented in the journal, then CMAJ will have a severely limited potential for “greatness.” News reports are not the only issue here. Even if news reports were to be eliminated (which the Committee strenuously opposes), editors would feel intimidated in their efforts to write editorials or publish articles about controversial issues. As long as CMA/CMAH believes that it is appropriate to require the editors to constrain their point of view, suppress debate, and respond to the pressures of political and commercial alliances, the journal will not be able to mature as a leader among the world's medical journals. Furthermore, if authors perceive that the CMA or the CMAH are in a position to influence or suppress any kind of material, they will no longer believe that their work will get a fair hearing by an impartial editorial staff. Such an occurrence could well result in a loss of some of the most important manuscript submissions from Canada and elsewhere. It may also undercut the willingness of reviewers and other Canadian physicians who make voluntary contributions of their time to CMAJ.

8. The role of the Journal Oversight Committee. The CMAJ's JOC has not been viewed by the editors as a group to whom they can turn for swift action in a crisis. The editors did not seek support from the JOC while the conflict was occurring, but merely reported to the JOC after the fact. As noted before, we find the editors remiss in their hesitation to approach the JOC. That being said, the “letter from the editors”2 was sent to the JOC on Dec. 2, 2005. The letter concluded with a request that “the Journal Oversight Committee work toward the re-establishment of the editorial independence of the journal.” This request elicited no response until late January, when the editors received nothing more than a request for further information about the management of the news department. This included the query “Was the CMAJ Editorial Board consulted before the article was commissioned?” which reveals a distressing lack of understanding of the lack of a role of the editorial board in the day-to-day running of a biweekly publication. (See recommendation 3.)

We believe that the JOC has become an instrument through which CMA/CMAH can complain about CMAJ content considered politically inconvenient. In general, the JOC has had some mitigating effect, drawing conclusions in particular instances that favour the journal's right to represent a diversity of opinion. However, the JOC has functioned to date as a reactive body. An attempt by the JOC in May 2003 to bring a motion before the CMA board to formally enshrine the journal's independence came to nothing. As far as we are aware, the JOC has not pursued the matter further, although it is well positioned to do so.

Concerns have also been raised by the journal's editors with respect to the structure and operation of the JOC. For at least the first year of its existence, the JOC had no chair. The chairperson who was eventually selected was also the publication liaison member from the CMA board, a choice that strikes the Committee as procedurally inappropriate. For several months the composition of the JOC also included the then president-elect of the CMA, which represents a conflict of interest. The current composition includes 2 members of the CMA board, one of whom is now chair of the JOC.

There is no process for briefing new JOC members on the history and vision of the journal, accepted norms of medical journal publishing, or the principles of editorial independence. Minutes of meetings are not made available. The timing and agenda of JOC meetings, as well as the list of attendees, seem to be directed by CMA/CMAH rather than by the JOC.

After the transfer of CMAJ from the CMA to CMAH, a proposal was made to alter the terms of reference of the JOC and was circulated for approval. No process of thorough deliberation was apparent. CMAJ's editors expressed concern over the proposed changes and put forward a draft set of revisions for discussion. The editors have not been informed of any progress.

In sum, the editors have indicated that they perceive a lack of responsiveness on the part of the JOC. Rightly or wrongly, this lack of confidence in the JOC needs to be corrected. If editors are doing their job, criticizing any aspect of the health care system that seems deficient, disputes are bound to occur. A critical function of an oversight committee should be to protect the editor from undue inside or outside influence. To do so requires that the JOC respond swiftly to any urgent concern expressed by any party.

Conclusions

Despite claims by the CMA, the Committee concludes that CMAJ's editorial autonomy is to an important degree illusory. The Canadian Medical Association and CMA Holdings must make a choice about what kind of publication it wants CMAJ to be. That choice is between, on the one hand, accepting as inviolable the editors' responsible exercise of editorial independence, and, on the other, clarifying for readers, researchers, physicians, the public and the press that the conduct of the editors must be consonant with the political, ideological and strategic objectives of the CMA. We categorically reject the view that the content of the news section can be subject to review by the CMA or the JOC and at the same time the rest of the journal could be considered fully independent. Independence must include all sections of the CMAJ. In our view, any attempt by the CMA to impose its influence on the editors would be catastrophic for the CMAJ's reputation as well as damaging to the reputation of the CMA.

Recommendations

1. It is not the role of this Committee to determine what course of action serves the best interests of the CMA and its members. Instead, it is up to the CMA to make this decision. If the decision favours rigorous editorial independence, specific criteria should be included in the editor's job description and contract. However, if CMA/CMAH wishes to exert control over any of the journal's content, readers and contributors need to know about it. They need to know under what conditions the information provided in CMAJ's peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed pages is produced.

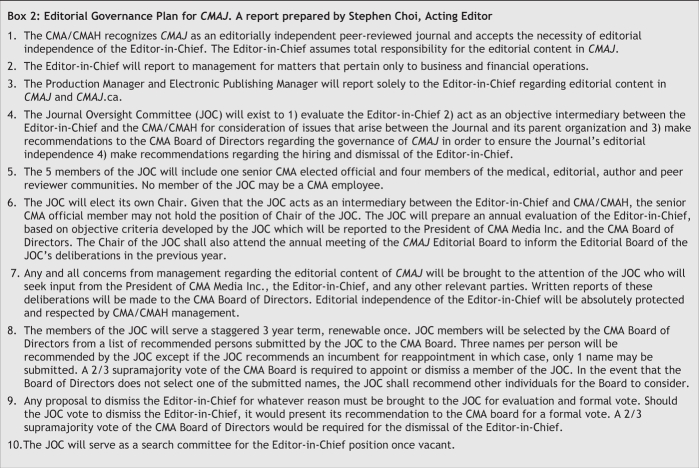

2. If CMA/CMAH does not wish to adhere to the principles of editorial autonomy as articulated by international standards, then, in the view of this Committee, the implications of this view need to be clarified. In our view, it is incumbent upon the JOC to present this matter to the CMA Board for reasoned debate. We strongly recommend that specific policies on editorial independence be formulated and approved. Depending on the outcome of these deliberations, editors, staff and editorial board members will have to decide whether to continue to serve.

3. The purpose, structure and governance of the JOC must be re-examined. The JOC should support the CMAJ's independence, be ready to deal with criticisms rapidly, and quickly diffuse emotionally charged situations before they reach an explosive potential. JOC members should be briefed with regard to the history and objectives of the CMAJ, their responsibilities, and should have a working knowledge of the standards of editorial responsibility and autonomy as agreed upon by international bodies. For their part, CMAJ editors have a responsibility to make proper use of the JOC when controversies arise. We strongly endorse the proposal by the current acting editor (Box 2).

Box 2.

Lastly, the occasional direct confrontation between CMA and CMAH officials and members of the CMAJ staff are extremely damaging, not only to the morale of the editors, but to the editors' willingness to publish controversial items. The CMA and CMAH must vigorously discourage this kind of action.

Respectfully submitted, Feb. 27, 2006.

@ See related articles pages 901 and 953

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Early release. Published at www.cmaj.ca on Feb. 28, 2006.

Correspondence to: Jerome P. Kassirer, jerome.kassirer@tufts.edu; Frank Davidoff, fdavidoff@cox.net; Kathryn O'Hara, kathryn_ohara@carleton.ca; Donald A. Redelmeier, dar@swri.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Eggertson L, Sibbald B. Privacy issues raised over Plan B: women asked for names, addresses, sexual history. CMAJ 2005;173(12):1435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.CMAJ editors. A letter from the editors of CMAJ concerning a recent infringement of editorial independence. 2005; Dec 2.

- 3.Eggertson L, Sibbald B. Memo from CMAJ news reporters regarding the Plan B story. 2005; Dec 2.

- 4.Ettema JS, Glasser TL. On the epistemology of investigative journalism. In: Adam GS, Clark RP. Journalism: the democratic craft. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 126-40.

- 5.Official notice [editorial] CMAJ 1911;1(1):57-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.The Ontario Medical Council [editorial]. CMAJ 1911;1(2):151-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Lessons from cisapride [editorial]. CMAJ 2001;164(9):1269. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Eggertson L, Sibbald B. Hospitals battling outbreaks of C. difficile. CMAJ 2004;171:19-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Medical journalism. I: Men and causes [editorial]. CMAJ 1965;92(7):374. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Medical journalism. IV: The position of professional periodicals [editorial]. CMAJ 1965;92:629. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.