Abstract

Noncontact, depth-resolved, optical probing of retinal response to visual stimulation with a <10-μm spatial resolution, achieved by using functional ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography (fUHROCT), is demonstrated in isolated rabbit retinas. The method takes advantage of the fact that physiological changes in dark-adapted retinas caused by light stimulation can result in local variation of the tissue reflectivity. fUHROCT scans were acquired from isolated retinas synchronously with electrical recordings before, during, and after light stimulation. Pronounced stimulus-related changes in the retinal reflectivity profile were observed in the inner/outer segments of the photoreceptor layer and the plexiform layers. Control experiments (e.g., dark adaptation vs. light stimulation), pharmacological inhibition of photoreceptor function, and synaptic transmission to the inner retina confirmed that the origin of the observed optical changes is the altered physiological state of the retina evoked by the light stimulus. We have demonstrated that fUHROCT allows for simultaneous, noninvasive probing of both retinal morphology and function, which could significantly improve the early diagnosis of various ophthalmic pathologies and could lead to better understanding of pathogenesis.

Keywords: electroretinogram, functional optical coherence tomography, inner plexiform layer, photoreceptors, retinal imaging

The vertebrate retina consists of several distinct layers: nuclear layers containing cell bodies can be differentiated from plexiform layers with axons and dendrites forming the neuronal network that preprocesses light-evoked signals before transmission to the brain. Early stages of retinal disorders are often confined to one of these layers and are manifested by both morphological abnormalities and impaired physiological responses. Detection of such pathologies requires high-resolution imaging methods. Various imaging modalities such as fundus photography, ultrasound imaging, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are clinically used for imaging retinal morphology. OCT is an emerging imaging technique that allows for noncontact, in vivo visualization of biological tissue morphology with a micrometer-scale resolution at imaging depths of 1–2 mm (1–3). Currently, electrophysiological tests such as electroretinography (ERG) (4) and multifocal ERG (5) are used for clinical assessment of retinal function.

More then 25 years ago, it was observed that the isolated retina when stimulated with visible light changes the amount of transmitted near-infrared light (NIR) (6, 7). Photoreceptors (PRs) were determined to be the main source of this effect, and in the following years, this method was used for investigation and quantitative evaluation of the activation of the PR G protein transducin and the time course of transduction events (8–10 and reviewed in ref. 11). In the last few years, other physiological processes at the cellular and subcellular level such as membrane depolarization (12), cell swelling (13), and altered metabolism have been found to cause small changes in the local optical properties of neuronal tissue that are detectable by measurement of light-scattering signals. In studies carried out in isolated retinas (14) and retinal-slice preparations (15), changes of NIR transmission and scattering have been recorded from retinal layers, including the inner retina before and after light stimulation.

Recently, a study on in vivo imaging of light-triggered physiological responses recorded at the surface of the retina (changes of local blood flow and metabolism) was published (16). Advances in laser technology have allowed the improvement of the OCT technique and the acquisition of depth profiles of biological tissue with an axial resolution <3 μm (17–23). Clinical studies in ophthalmology have demonstrated that ultrahigh resolution OCT (UHROCT) is capable of noncontact, real-time, visualization of retinal morphology both in healthy and pathological retinas with sub 3 μm axial resolution (24–26). Furthermore, the large sensitivity of OCT (≈100 dB) allows for detection of very weak optical signals. Preliminary results on using standard axial (≈20 μm) resolution OCT for imaging brain function (27) in animal models and propagation of action potentials in isolated nerve fibers (28) have been reported.

In this article, we focus on physiological responses and demonstrate that functional UHROCT (fUHROCT) can be used successfully for noncontact, spatially resolved probing of physiological responses from light-stimulated retinal sublayers.

Results

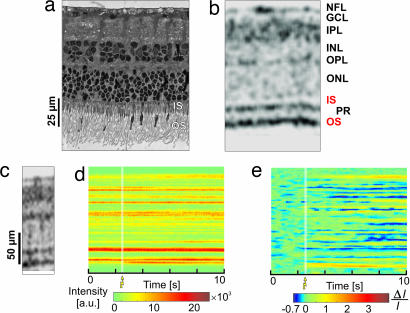

Fig. 1a shows a histological cross-section, and Fig. 1b shows the corresponding morphological UHROCT tomogram acquired from a location in the retina where functional measurements were performed. Retinal layers with high optical reflectivity, such as the nerve fiber layer and the plexiform layers, appear dark in UHROCT tomograms because of increased light scattering. Direct comparison between Fig. 1 a and b demonstrates that the spatial resolution of UHROCT is sufficient to clearly visualize all retinal layers. The histological cross-section and the UHROCT tomogram exhibit an intact outer segment (OS) of the PR layer, indicating morphological completeness for signal transduction.

Fig. 1.

Morphological and functional retinal imaging with UHROCT. Comparison between a histological cross-section (a); an OCT morphological tomogram (b) of the isolated retina demonstrates the ability of UHROCT to visualize the layered retinal structure. OCT M-scan (d; optical signal measured at one position over time) and differential M-scan (e; produced from d by subtracting the background signal, calculated as a time average of the preactivation depth scans from the entire M-scan) are compared with a morphological UHROCT tomogram (c) of the location where the OCT M-scan was acquired. The white strips mark the onset and duration of the white light flash.

To test whether UHROCT is capable of detecting changes in the retina reflectivity triggered by light stimulation, a dark-adapted, isolated living retina was exposed to a single flash (SF) of white light at three different intensities, whereas fUHROCT data were acquired synchronously with ERG recordings. Fig. 1d presents a raw-data fUHROCT M-scan that shows the retinal depth reflectivity profile as a function of time. Comparison of the M-scan with a 2D morphological UHROCT image (Fig. 1c) allows correlation to the morphological origin of the optical reflectivity changes observed in the fUHROCT images. To improve the visibility of the stimulus-induced optical changes, the raw-data M-scan (Fig. 1d) was normalized to the optical background (see Methods), and a differential M-scan (Fig. 1e) was generated. The white strips on Fig. 1 d and e indicate the onset and duration of the light flash. The differential M-scan exhibited pronounced increase in the optical reflectivity in the area corresponding to the PR OS for the time period immediately after the light flash. Both positive and negative changes in the tissue reflectivity were observed in the inner retina.

To rule out the possibility that the observed optical changes are imaging artifacts, three types of control experiments were carried out. Each type was designed to alter the normal physiological state of a specific group of retinal neurons by using either dark adaptation vs. light stimulation or pharmacological inhibition. During the first type of experiment, dark scans (DS), 10-s fUHROCT recordings in dark-adapted retinas without light stimulus, were alternated with SF measurements of the same duration after an intensity-dependent dark-adaptation time of ≤3 min at a fixed location in the retina. In the second type of experiment, SF recordings were acquired from preparations in which the normal response of the PRs to light stimulation was inhibited by superfusing the retina with 44 mM potassium solution, corresponding to a potassium equilibrium potential at the level of the PR dark membrane potential. In the third type of experiment, pharmacological drugs [30 μM solutions of l-2-amino-4-phosphono butyric acid (APB) and 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo-f-quinoxide (NBQX)] (29, 30) were used to block inner retina function, specifically, the normal response of the ON- and OFF-bipolar cells.

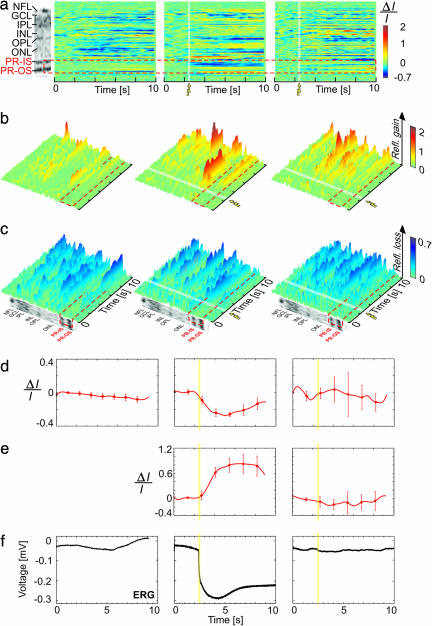

Fig. 2 summarizes results from the first and second type of experiments. Fig. 2a compares differential M-scans acquired during DS, SF, and SF + PR inhibition with a morphological scan (Left). The red dashed line marks the boundaries of the PR layer. Fig. 2 b and c show the same M-scans in 3D for better visualization of the time course and magnitude of the positive and negative optical changes. Fig. 2 d and e present traces extracted from the differential M-scans at locations corresponding to the inner segment (IS) and OS of the PR layer. These traces show the average retinal response and the SD for 10 selected consecutive measurements. Fig. 2 f shows the corresponding traces from the ERG recordings.

Fig. 2.

fUHROCT data: the PR response. (a) A morphological retinal image compared with differential M-scans corresponding to DS (no light stimulus; Left), an SF scan in normal retina (Middle), and an SF scan in retina with inhibited PR function (Right). The red dashed line marks the location of the PR layer in all M-scans. (b and c) Visualization of the differential M-scans in 3D, emphasizing the positive and negative optical signals, respectively, is shown. (d and e) The time course of the optical signals extracted from the IS (d) and OS (e) of the PR, respectively. The error bars show the SD computed by averaging 10 differential M-scans. (f) The ERG recordings acquired simultaneously with the fUHROCT M-scans. The white (a–c) and yellow (d–f) strips in the M-scans and the extracted time courses mark the onset and time duration of the SF light stimulus.

As expected during DS (no light stimulus), neither the optical reflectivity of the PR layer nor the ERG signals changed significantly with time. In the first and second type of experiments, during SF recordings conducted in normal dark-adapted retinas, the reflectivity of the IS and OS of the PR layer exhibited significant intensity-dependent negative and positive changes, respectively, after application of the light stimulus. The ERG recordings showed a large negative response because the absence of pigment epithelium and application of a bright light stimulus reduced the ERG to its PIII component in respect to the normal function of the PRs. The onset of both the optical and the ERG signals correlated well with the onset of the light flash. In the case of K+-inhibited PR function, the optical changes observed in the IS and OS of the PR layer appeared close to the optical background level and showed no correlation to the onset of the light stimulus. Similar signals were observed in the ERG recording.

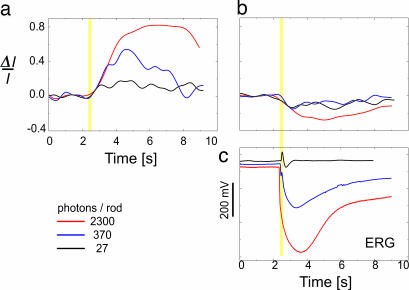

Fig. 3 depicts stimulus-dependent PR responses detected by fUHROCT. The positive (Fig. 3a) and negative (Fig. 3b) responses are time courses of ensemble averages of 10 consecutive differential optical signals extracted from a 5- to 6-μm-wide strip of the IS and OS reflexes of the PR, respectively. The illumination corresponds to 27 (black), 370 (blue), and 2,300 (red) photons/rod/flash. The flash is indicated by a yellow stripe. Corresponding ERG recordings are also presented (Fig 3c).

Fig. 3.

fUHROCT data: the stimulus-dependent PR response. (a and b) Time course of ensemble averages of 10 consecutive differential optical signals extracted from a 5- to 6-μm-wide strip of the IS and OS reflexes of the PR, respectively. The illumination corresponds to 27 (black), 370 (blue), and 2300 (red) photons/rod/flash. The flash is indicated by a yellow stripe. (c) Corresponding ERG.

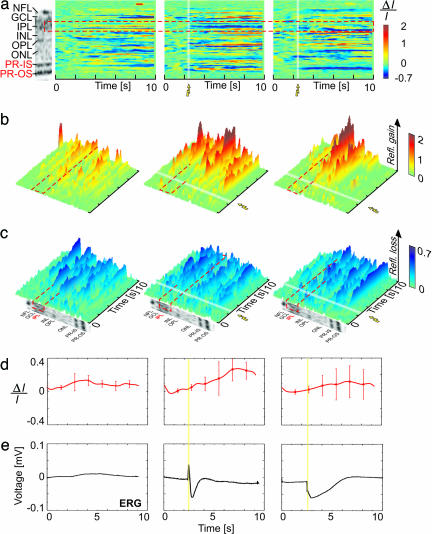

Fig. 4 summarizes results from the first and third type of experiments. Fig. 4 a compares differential M-scans acquired during DS, SF, and SF + APB + NBQX inhibition with a morphological scan (Fig. 4 a Left). The red dashed line shows the borders of the retinal inner plexiform layer (IPL). Considering that the IPL does not have a clearly defined sublayered morphology and appears fairly homogeneous within the axial resolution limits of this experiment, the optical traces extracted from each differential M-scan were spatially averaged over the full width of the IPL. The small amplitudes obtained from the IPL did not allow getting significantly different responses at respective light intensities. Fig. 4 b and c show the same M-scans in 3D for better visualization of the time course and the magnitude of the observed positive and negative optical changes. Fig. 4 d and e show the averaged optical signals and the corresponding traces from the ERG recordings. The white strips in the differential M-scans and the yellow strips in the optical and ERG traces mark the activation of the light stimulus.

Fig. 4.

fUHROCT data: the IPL response. (a) A morphological retinal image compared with differential M-scans corresponding to a DS (no light stimulus) (Left), an SF scan in normal retina (Middle), and an SF scan in retina with inhibited bipolar cell function in the IPL (Right). The red dashed line marks the boundaries of the IPL in all M-scans. (b and c) A 3D visualization of the positive and negative optical signals in differential M-scans. (d) The time course of the optical signals (average across the width of the IPL) extracted from the IPL. The error bars show the standard deviation computed by averaging 10 differential M-scans. (e) The ERG recordings acquired simultaneously with the fUHROCT M-scans. The white (a–c) and yellow (d–e) strips in the M-scans mark the onset and time duration of the SF light stimulus.

During DS, both the average optical reflectivity of the IPL as well as the ERG traces exhibited slow, small-magnitude changes close to the measured physiological noise level. During SF recordings conducted in normal dark-adapted retinas, the averaged IPL reflectivity exhibited changes over time that correlated with the light-stimulus onset. In this case, the brightness of the light stimulus was adapted to result in a pronounced b-wave in the ERG recording, an indication for proper function of the inner retina. The ERG trace showed both a positive b-wave and a negative PIII potential, corresponding to a properly functioning visual pathway from the PR layer to the nerve fiber layer. Changes in the optical reflectivity, correlated with the light stimulus, were also observed in the outer plexiform layer (OPL). The application of APB and NBQX drugs during the SF experiments resulted in altered reflectivity of the IPL and OPL. In this case, the average optical traces extracted from the IPL exhibited low-magnitude changes, uncorrelated with the onset of the light stimulus. As expected, blocking the PR/bipolar cell synapses caused the disappearance of the b-wave in the corresponding ERG recording, whereas the PIII-negative response reappeared. As reported in ref. 30, the presence of the PIII potential corresponds to normal function of the PRs, whereas the loss of the b-wave is generally attributed to blocked transmission from the PRs to the bipolar cells.

Discussion

The results described above clearly demonstrate that fUHROCT is capable of detecting small changes in the optical reflectivity of living retinas caused by external stimuli with high-spatial resolution. The control experiments certify that the observed signals appear because of statistically significant changes in the retinal reflectivity due to the altered physiological state triggered by light-stimuli. fUHROCT experiments were carried out on 14 isolated, noninhibited retinas, and >370 SF M-scans were acquired at 30 different locations. Experiments with pharmacological inhibition were carried out in six retinas. Optical signals extracted from the IS/OS of the PR layer exhibited excellent correlation with the ERG recordings and the light-stimulus onset, as well as very high reproducibility (>72%). Averaged optical traces extracted from the IPL were well correlated with the light-stimulus onset and the ERG but exhibited fairly low reproducibility in terms of the shape and sign of the optical changes at different transversal locations.

The differential magnitudes (i.e., the signals initiated by the stimulus compared with the dark-adapted ones) of the observed positive and negative optical changes were time-dependent and varied between 5% and 80% depending on the location within the retina (PR or IPL) and the type of experiment. Statistical analysis performed on sets of 10 consecutive M-scans showed that in the case of SF recordings from normal dark-adapted retinas, the optical traces in the PR and the IPL after the light flash were statistically different (P = 0) from the optical background (prestimulation). In the case of DS recordings or the KCL- and APB + NBQX-inhibited retinas, there was no statistical difference (0.93 < P < 0.98) between the prestimulus and poststimulus recorded data.

UHROCT is sensitive to local variations in the reflectivity of the imaged object, which can be related to changes in its shape, size, and refractive index of different morphological features. Although the exact mechanism that causes the observed optical signals is currently not known, a number of physiological processes occurring during and immediately after light stimulation may result in time-dependent changes of the retinal reflectivity.

Origin of the Optical Signals in the PR Layer.

Changes in light transmission and scattering in the PR OS layer have been reported by various groups. NIR scattering signals have been extensively investigated in bovine rod OS in a number of studies. Their origin was described (6, 7), and subsequently NIR optical measurements were used to investigate the activation and/or effector interaction of the G protein transducin (8–10). Dawis and Rossetto (15) observed a relatively slow increase in light transmission of light-activated rod OSs of unknown origin in the anuran retina. Yao et al. (14) used a modified standard resolution OCT system with fixed-depth selection to record a light-evoked decrease of NIR scattering in the PR and an increase in the ganglion cell layer. Their work suggested that cell swelling and shrinkage and membrane depolarization resulting from the ionic fluxes are most probably the cause for the observed optical changes. This hypothesis was supported by the swelling and shrinking of cells produced by ionic fluxes associated with membrane polarization as a possible cause for these effects, which is supported by the voltage dependence of the amount of light scattered by Aplysia axons during action potentials (12).

PRs hyperpolarize during light stimulation, which may result in a temporary modulation of the optical reflectivity of the cell membrane. However, scattering changes observed in our study are relatively slow and correspond more to the time course of ion shifts involved in ERG generation than to the rapid hyperpolarization of the PR membrane evoked by light stimuli. In addition, we observe two different scattering signals, one at the level of the OS and the other at the level of the IS. Whereas the OSs are packed with thousands of densely stacked discs that contain the photosensitive agent rhodopsin and the G protein that mediates phototransduction, the IS ellipsoids of the PR consist of mitochondria tightly packed in parallel (31). Altered metabolic rates during light stimulation could cause changes in the mitochondrial refractive index, which in turn may result in decrease of the PR IS reflectivity. Actin-dependent retinomotor activity is a general phenomenon of the nonmammalian vertebrate PRs and pigment epithelial processes (32). Currently, there is no evidence for this phenomenon in mammalian retinas. However, adaptive alignment and realignment toward the direction of highest light intensity (pupil) has been described and attributed to the activity of IS cytoskeletal elements, actin fibers, and microtubules (33, 34). We cannot exclude that minute light-induced motor responses could contribute to the optical reflectivity changes observed in the IS/OS of the PR.

The cross-section of the imaging fUHROCT beam was ≈10–20 μm in diameter, which, considering the size of a single PR (≈2 μm in diameter), was sufficient to illuminate ≈15–50 PRs, assuming a fill factor of 0.5 of the PR matrix. The large number of simultaneously probed PRs may account for the relatively large magnitude and the high reproducibility rate of the optical signals detected by fUHROCT. Because the functional experiments were conducted in isolated retinas, the retinal pigment epithelium was removed, which prevented normal regeneration of the visual pigment rhodopsin. Temporary and, later, permanent bleaching of the PRs resulted in gradual decrease in signal magnitude, followed by complete loss of the optical signals over time when multiple SF recordings were acquired. If fUHROCT experiments were conducted in vivo, the PR bleaching would be temporary, which should improve the reproducibility rate of the detected optical signals significantly.

Origin of the Optical Signals in the IPL/OPL.

The neuropil of the retinal IPL and OPL has a very complex microstructure; the OPL contains the dendritic extensions of PRs, horizontal and bipolar cells; in the IPL, interactions of a variety of specialized amacrine cells, axonal terminals of ON- and OFF- bipolar cells, and ganglion cells take place. All synapses contain a large number of dynamically cycled microvesicles, whereas the dendrites are packed with round mitochondria, ribosomes, and neurofilaments. Exposure of a dark-adapted retina to light causes transmission of electrical potentials through the axonal and dendritic extensions of the different cells, which in turn polarize the cell membranes and change both the synaptic states and the mitochondrial metabolism. It was expected that these processes would cause positive changes in the IPL and OPL reflectivity after onset of the light stimulus, with some spatial variation over the thickness of each layer, as well as time-dependent variations in the optical signal magnitude resulting from differences in the time course of the transmitted electrical signals generated by the different cells. Such changes were indeed observed in most of the SF experiments. On few occasions, however, the M-scans exhibited a slow decrease in the IPL and OPL reflectivity immediately after the SF. A possible cause for the decrease in the IPL and OPL reflectivity could be the swelling of Müller cells that more or less follows the transmission of electrical signals within the retina. Müller cells are Glia cells that extend vertically through the entire thickness of the retina. If the body of a swollen Müller cell partially overlaps with the fUHROCT imaging beam, light would propagate through the Müller cell with very little scattering, which in turn would locally reduce the reflectivity of both plexiform layers.

This article focused on optical changes observed only in selected retinal layers: PR and IPL. The reason was that, in general, retinal nuclear layers such as the inner nuclear, outer nuclear, and the ganglion cell layers have low optical reflectivity, which would render detection of small optical signals related to retinal physiology very difficult. The retinal nerve fiber layer (NFL) is comprised of the axonal extensions of ganglion cells and is highly reflective. Therefore, it would be of interest to investigate the optical response of the NFL during propagation of action potentials related to SF light stimulation of the retina. In this study, however, fUHROCT recordings were acquired mostly from the midventral part of the rabbit retina where the NFL was very thin, which impeded the extraction of optical traces.

The complex morphology and physiology of the retinal plexiform layers account for the short time scale variations in the IPL and OPL reflectivity observed in the functional SF M-scans, as well as the fairly low reproducibility rate of the optical signals in terms of shape and sign. Future experiments and technological development may allow for separation of the contributions from different types of cells and their physiological state to the total optical response of the retinal plexiform layers to SF stimulation.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that fUHROCT can be used successfully to probe light-induced retinal response noninvasively and with high-depth resolution. Provided that better understanding of the relation between retinal optical reflectivity and physiology is gained by future experiments, fUHROCT could potentially develop as a clinical method for simultaneous high-resolution imaging of the morphology and physiology of the human retina.

Methods

UHROCT System.

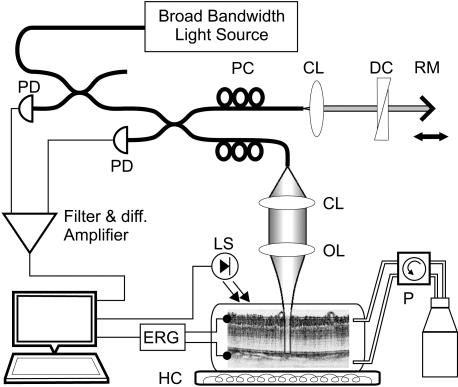

A schematic of the experimental apparatus is presented in Fig. 5. Optical recordings from isolated, living rabbit retinas were acquired by using an UHROCT system designed for optimal performance in the 1,100- to 1,500-nm wavelength range. The system was illuminated by a state-of-the-art fiber laser with emission spectrum centered at 1,250 nm, a spectral bandwidth of 150 nm, and output power of 250 mW. A light source with a longer central wavelength than visible light was chosen for the current study to avoid unwanted stimulation of the dark-adapted retinas during the optical recordings. The UHROCT system provided 3.5- × 10-μm (axial × lateral) resolution in biological tissue and a sensitivity of 100 dB for 2 mW of incident power at the sample. The time resolution achieved, 4.5 ms, was limited by the scan rate of the galvanometric scanner used in the reference arm of the UHROCT system. To prevent local heating of the retinal tissue in the vicinity of the optical beam focus, the optical beam was blocked at all times except during acquisition of morphological UHROCT or fUHROCT tomograms.

Fig. 5.

Schematic of the fUHROCT set up. Isolated, living retinas were kept in a heated chamber (HC) connected to a perfusion system (P). The UHROCT system provided a 3.5 × 10-μm (axial × lateral) spatial resolution and a 4.5-ms time resolution. The optical data acquisition was synchronized with the white light stimulus and the ERG recordings. CL, collimation lens; OL, objective lens; DC, dispersion compensation; RM, reference mirror; PC, polarization controllers; PD, photodiodes; LS, light stimulus.

Isolated Retina Sample Preparation.

Eyes from anesthetized rabbits were enucleated, and retinas were isolated, positioned in a superfusion chamber under a nylon mesh, and maintained at a constant temperature of 33°C in oxygenated buffered Ames medium. The retinal pigmented epithelium was removed to allow for better perfusion and easy administration of pharmacological drugs to the isolated retina. The viability of the isolated retinal samples was tested by acquiring ERG recordings during SF light stimulation. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Data Acquisition and Processing.

Because removal of the retinal pigment epithelium can damage the OS of the PRs and render them dysfunctional, morphological 2D UHROCT tomograms were acquired from chosen locations in the living retina before the functional recordings to ensure the morphological intactness of the PR layer. The chosen locations were carefully marked for subsequent histological analysis, intended to verify that none of the PRs were damaged at the specified areas.

During the functional experiments, the isolated retinas were stimulated with single, 200-ms-long, white light flashes. The brightness of the light stimulus was varied >2 orders of magnitude. Assuming a 2-μm2 collection area per rod, the average number of photons per flash per PR, calibrated to the maximum sensitivity at 505 nm, was set to ≈27, 370, and 2,300 photons/rod/flash; thus staying well beneath the bleaching limit and allowing for recovery within the 2- to 3-min interscan period (35). The time course of the light stimulus consisted of a 2.5-s prestimulation, a 0.2-s single, white light flash, and a 7.3-s poststimulation period followed by an intensity-dependent adaptation time of ≤3 min. The UHROCT depth-scans were combined to form 2D raw-data M-scans presenting the retinal reflectivity profile as a function of time (similar to M-scans in ultrasound imaging).

The processing of the optical data involved application of a cross-correlation algorithm to account for any movement of the retina caused by the solution flow; calculation of the optical background (average over the prestimulation depth scans for each individual M-scan) and generation of differential M-scans showing ΔI/I, where I is the total average optical signal intensity within a depth scan and ΔI is the difference between the signal and the time averaged optical background determined from the prestimulation depth scans of the raw-data M-scans. Fast variations in the optical speckle pattern were suppressed by applying band pass filter.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. P. Hofmann (Institute of Medical Physics and Biophysics, Charité, Berlin) and A. Grinvald (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) for the helpful scientific discussions. We are grateful for the financial support provided by the Östereichische National Bank, Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (FWF) P14218-PSY, FWF Y159-PAT, the University of Waterloo Startup Fund, the Christian Doppler Society, European Community Grant CORTIVIS QLRT-2001-00279, Femtolasers, Inc., Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., and IPG Photonics.

Abbreviations

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- ERG

electroretinography

- NIR

near-infrared light

- UHROCT

ultrahigh-resolution OCT

- fUHROCT

functional UHROCT

- OS

outer segment

- PRs

photoreceptors

- SF

single flash

- DS

dark scan

- APB

l-2-amino-4-phosphono butyric acid

- NBQX

2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo-f-quinoxide

- IS

inner segment

- IPL

inner plexiform layer

- OPL

outer plexiform layer

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Huang D., Swanson E. A., Lin C. P., Schuman J. S., Stinson W. G., Chang W., Hee M. R., Flotte T., Gregory K., Puliafito C. A., et al. Science. 1991;254:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujimoto J. G., Brezinski M. E., Tearney G. J., Boppart S. A., Bouma B., Hee M. R., Southern J. F., Swanson E. A. Nat. Med. 1995;1:970–972. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fercher A. F., Drexler W., Hitzenberger C. K., Lasser T. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2003;66:239–303. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholl H. P., Zrenner E. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2000;45:29–47. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hood D. C., Odel J. G., Chen C. S., Winn B. J. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2003;23:225–235. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harary H. H., Brown J. E., Pinto L. H. Science. 1978;202:1083–1085. doi: 10.1126/science.102035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann K. P., Uhl R., Hoffmann W., Kreutz W. Biophys. Struct. Mech. 1976;2:61–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00535653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahlert M., Hofmann K. P. Biophys. J. 1991;59:375–386. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahlert M., Pepperberg D. R., Hofmann K. P. Nature. 1990;345:537–539. doi: 10.1038/345537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pepperberg D. R., Kahlert M., Krause A., Hofmann K. P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:5531–5535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arshavsky V. Y., Lamb T. D., Pugh E. N., Jr. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002;64:153–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.082701.102229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stepnoski R. A., LaPorta A., Raccuia-Behling F., Blonder G. E., Slusher R. E., Kleinfeld D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:9382–9386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srinivas S. P., Bonanno J. A., Lariviere E., Jans D., Van Driessche W. Pflügers Arch. 2003;447:97–108. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao X. C., Yamauchi A., Perry B., George J. S. Appl. Opt. 2005;44:2019–2023. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.002019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawis S. M., Rossetto M. Vis. Neurosci. 1993;10:687–692. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800005381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson D. A., Krupsky S., Pollack A., Aloni E., Belkin M., Vanzetta I., Rosner M., Grinvald A. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging. 2005;36:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drexler W., Morgner U., Kärtner F. X., Pitris C., Boppart S. A., Li X. D., Ippen E. P., Fujimoto J. G. Opt. Lett. 1999;24:1221–1223. doi: 10.1364/ol.24.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Považay B., Bizheva K., Unterhuber A., Hermann B., Sattmann H., Fercher A. F., Drexler W., Apolonski A., Wadsworth W. J., Knight J. C., et al. Opt. Lett. 2002;27:1800–1824. doi: 10.1364/ol.27.001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vabre L., Dubois A., Boccara A.C. Opt. Lett. 2002;27:530–532. doi: 10.1364/ol.27.000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartl I., Li X. D., Chudoba C., Ghanta R. K., Ko T. H., Fujimoto J. G., Ranka J. K, Windeler R. S. Opt. Lett. 2001;26:608–610. doi: 10.1364/ol.26.000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bizheva K., Považay B., Hermann B., Sattmann H., Drexler W., Mei M., Holzwarth R., Hoelzenbein T., Wacheck V., Pehamberger H. Opt. Lett. 2003;28:707–709. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.000707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unterhuber A., Považay B., Hermann B., Sattmann H., Drexler W., Yakovlev V., Tempea G., Schubert C., Anger E. M., Ahnelt P. K., et al. Opt. Lett. 2003;28:905–907. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.000905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drexler W. J. Biomed. Opt. 2004;9:47–74. doi: 10.1117/1.1629679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drexler W., Morgner U., Ghanta R. K., Kartner F. X., Schuman J. S., Fujimoto J. G. Nat. Med. 2001;7:502–507. doi: 10.1038/86589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drexler W., Hermann B., Schubert C., Sattmann H., Ahnelt P. K., Drexler W. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003;121:695–706. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gloesmann M., Hermann B., Schubert C., Sattmann H., Ahnelt P. K., Drexler W. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2003;44:1696–1703. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uma Maheswari R., Takaoka H., Homma R., Kadono H., Tanifuji M. Opt. Comm. 2002;202:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazebnik M., Marks D. L., Potgieter K., Gillette R., Boppart S. A. Opt. Lett. 2003;28:1218–1220. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.001218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen E. D., Miller R. F. Brain Res. 1999;831:206–228. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01448-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiells R. A., Falk G. Vis. Neurosci. 1999;16:503–511. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899163119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thar R., Kuhl M. J. Theor. Biol. 2004;230:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burnside B. Prog. Brain Res. 2001;131:477–485. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(01)31038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eckmiller M. S. Prog. Retin. Eye. Res. 2004;23:495–522. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enoch J. M., Birch D. G. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B. 1981;291:323–351. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breton M. E., Schueller A. W., Lamb T. D., Pugh E. N., Jr. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 1994;35:295–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]