Abstract

Chemokine-binding proteins represent a novel class of antichemokine agents encoded by poxviruses and herpesviruses. One such protein is encoded by the M3 gene present in the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) genome. The M3 gene encodes a secreted 44-kDa protein that binds with high affinity to certain murine and human chemokines and has been shown to block chemokine signaling in vitro. However, there has been no direct evidence that M3 blocks chemokine activity in vivo, nor has the nature of M3-chemokine interaction been defined. To better understand the ability of M3 to block chemokine activity in vivo, we examined its interaction with a specific subset of chemokines expressed in lymphoid tissues, areas where gammaherpesviruses characteristically establish latency. Here we show that M3 blocks in vitro chemotaxis induced by CCL19 and CCL21, chemokines expressed constitutively in secondary lymphoid tissues. Moreover, we provide evidence that chemokine M3 binding exhibits positive cooperativity. In vivo, the expression of M3 in the pancreas of transgenic mice inhibits recruitment of lymphocytes induced by transgenic expression of CCL21 in this organ. The ability of M3 to block the biological activity of chemokines may represent an important strategy used by MHV-68 to evade immune detection and favor viral replication in the infected host.

Chemokines and their receptors have a key role in immune homeostasis via their ability to regulate leukocyte migration, differentiation, and function (23). Disturbances in the physiological expression and function of chemokines are often associated with increased susceptibility to infections and autoimmune diseases (10).

Viruses have acquired and optimized molecules that interact with the chemokine system. These virus-encoded molecules are used to promote cell entry, facilitate dissemination of infected cells, and evade the immune response (15). So far, three classes of molecules that interact with the chemokine system have been identified: viral chemokine ligands, viral chemokine receptors, and chemokine-binding proteins (15, 18). Viral chemokines have been shown to function as agonists and/or antagonists in their interaction with mammalian chemokine receptors. Acting as agonists they facilitate viral infection and dissemination; as antagonists they inhibit recruitment of specific leukocyte populations, thus contributing to immune evasion. Viral chemokine receptors have also been described, but their role in viral pathogenesis is unclear. Recent studies have implicated virally encoded chemokine receptors in proliferation and migration of cells, as well as in the pathogenesis of Kaposi's sarcoma (22, 26, 32). The most recently discovered family of virus-encoded molecules capable of interfering with chemokine function is composed of the chemokine-binding proteins. This class of proteins shows no significant homology to mammalian proteins, which suggests that it may have evolved independently of mammalian genomic elements. The myxomavirus, for example, encodes the protein M-T7, which binds C, CC, and CXC chemokines with submicromolar affinity by interacting with the low-affinity proteoglycan binding site conserved in many chemokines (15). Other members of the chemokine-binding protein family disrupt the interaction of chemokine ligands with their cellular receptors. Members of this subgroup include proteins encoded by many poxviruses and M3, the first chemokine-binding protein found to be encoded by a herpesvirus. M3 is a 44-kDa protein encoded by murine gamma herpesvirus 68 (MHV-68). This protein binds chemokines of the CC, CXC, CX3C, and C families with high affinity and prevents chemokine-induced signal transduction in vitro (21, 27).

MHV-68 is a natural pathogen of murid rodents which bears homology to the human pathogens Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and Epstein-Barr virus (24, 31). Introduction of virus intranasally leads to a productive infection of respiratory epithelial cells, which is eventually controlled by CD8+ T cells (25). The initial productive infection is followed by dissemination of the virus to secondary lymphoid tissue and establishment of latency in B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (8).

Studies of a mutant MHV-68 containing a lacZ insertion disrupting the M3 open reading frame (ORF) suggested a role for M3 in establishing and maintaining latency in secondary lymphoid tissue (2). More recently, a mutant MHV-68 in which the M3 ORF was disrupted by insertion of a translational stop codon and frameshift mutation was found to be attenuated after intracerebral inoculation but had no effect on viral latency or the induction of chronic arteritis (28). The phenotypes observed in both reports are likely to be caused by the inability of the M3-deficient viruses to block chemokine activity.

In this report, we used a multifaceted approach to further investigate the chemokine blocking potentials of M3. We report that M3 blocks chemotaxis induced in vitro by CCL19 and CCL21, chemokines constitutively expressed in lymphoid tissues and in lymphatic vessels in the periphery. Furthermore, we provide direct evidence for the ability of M3 to block chemokine function in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgene construction and microinjection.

A plasmid containing a segment of the rat insulin promoter 2 (RIP) and the rabbit β-globin poly(A) signal was generated by replacing the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) fragment in RIP-TNF-α-pBS (12) with the rabbit β-globin poly(A) DNA segment from a plasmid containing the CMV-EGFP transgene (20). The rabbit β-globin poly(A) signal was PCR amplified using the oligonucleotides 5′-ACAGAGGATATCACTCCTC AGGTGCAGGCTGC-3′, inserting an EcoRV site, and 5′-TGTCTCCTCGAGGTCGAGGGATCTCCATAAGAG-3′, inserting an XhoI site. TNF-α was released from RIP-TNF-α-pBS by EcoRV/SalI digestion and replaced by the rabbit β-globin poly(A) PCR-amplified fragment.

The cloning of the M3 ORF from infected-cell DNA into a baculovirus expression vector has been described previously (21). The M3 coding sequence was PCR amplified from this vector using the oligonucleotides 5′-ACAGAGGAATTCGCCGCCACCATGGCCTTCCTATCCACATCTGTG-3′, inserting an EcoRIsite and a consensus Kozak sequence, and 5′-ACAGAGGATATCTCAATGATCCCCAAAATACTCCAG-3′, inserting an EcoRV site. This PCR fragment was subcloned into the EcoRI/EcoRV site of the RIP-poly(A) vector described above, creating pRIPM3. The transgene (RM3) was released from pRIPM3 by SacII/KpnI digestion. The construction of the RCCL21 transgene has been described elsewhere (4). In this study, we used animals expressing CCL21a (line 21).

Separation of the RM3 transgene from vector DNA was accomplished by zonal sucrose gradient centrifugation as described (32). Fractions containing the transgene were pooled, microcentrifuged through Microcon-100 filters (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.) and washed five times with microinjection buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA).

Generation of transgenic mice.

The RM3 transgene was resuspended in microinjection buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA) to a final concentration of 1 to 5 μg/ml, microinjected into ([C57BL/6J × DBA/2]F2; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) eggs, and transferred into oviducts of ICR foster mothers (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.), according to published procedures (14). At 10 days after birth, a piece of tail from the resulting animals was clipped for DNA analysis. Identification of the transgenic mice was accomplished by PCR amplification of mouse tail DNA using specific primer sets. Specifically, the primers used for detection of the RM3 transgene were 5′-AGTGTGCAGGCTGCCTATCAGAATGT-3′ and 5′-TCTGATGTTTTAAATGATTTGCCCTCCC-3′, which are specific for a region in the rabbit β-globin poly(A) sequence. The endogenous ZP3 gene, used as an internal control, was amplified with the following primers: 5′-CAGCTCTACATCACCTGCCA-3′ and 5′-CACTGGGAAGAGACACTCAG-3′. PCR conditions were 94°C, 30 s; 60°C, 30 s; and 72°C, 60 s. The resulting transgenic mice were kept under pathogen-free conditions. All experiments involving animals were performed following the guidelines of the Schering-Plough Animal Care and Use Committee.

Histological analysis.

Tissues for light microscopic examination were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin and processed for paraffin sections. Routinely, 5-μm-thick sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For immunohistostaining, fresh frozen sections were first fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min and then dried and stored at −20°C. Slides were stained and analyzed as previously described (32). Purified primary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies for 30 min. After incubation with an avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) for 30 min, the tissue sections were finally stained with NovaRed (Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Primary antibodies used were anti-CD45 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) and a rabbit antiserum raised against M3 expressed in Escherichia coli.

Isolation of pancreatic islets of Langerhans.

Islets of Langerhans were isolated as previously described (11). Briefly, the common bile duct was clamped distal to the pancreatic duct junction at its hepatic insertion. The proximal common bile duct was then cannulated using a 27-gauge needle, and the pancreas was infused by retrograde injection of 2 ml of ice-cold collagenase solution (1.0 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in Hanks' balanced salt solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Pancreatic tissue was recovered and subjected to a 20-min digestion at 37°C. Subsequently, ice-cold Hanks' balanced salt solution was added, and the suspension was vortexed at full speed for 10 s. Released islets were filtered through a sterile 0.5-mm-pore-size mesh. Islets in the digested pancreata were enriched by Percoll centrifugation (density, 1.089/1.062). After a 10-min centrifugation at 800 × g, the islets were recovered from the gradient interface and hand-picked under a dissection microscope. Islets were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 20 mM HEPES, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% l-glutamine, and 2.5 ml of 7.5% NaHCO3 (all from Invitrogen) at 37°C under 5% CO2. The viability of the islets in culture was examined by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Cells and flow cytometry.

The cDNA for human CCR7 (hCCR7) was transfected into Ba/F3 cells using standard protocols. Stable expression was verified by specific binding of radiolabeled macrophage inflammatory protein 3β (MIP-3β) (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass.) and MIP-3β-dependent (R&D Systems) chemotactic response (data not shown). Stably transfected Ba/F3-hCCR7 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% l-glutamine, G418 (1 mg/ml; Geneticin) (all from Invitrogen), and mouse interleukin-3 (1 ng/ml; R&D Systems) at 37°C under 5% CO2. For flow cytometry, 106 cells were incubated with Fc block (5 μg/ml; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) and mouse IgG (300 μg/ml; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Cells were then stained with a human CCR7 specific mouse monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems) in phosphate-buffered saline-1% bovine serum albumin-0.1% sodium azide for 20 min at 4°C in the dark and then with a goat anti-mouse phycoerythrin-conjugated antibody (BD Pharmingen) for 10 min at 4°C in the dark. To determine viability, samples were subsequently stained with 20 μl of propidium iodide (5 μg/ml; Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.). Events were acquired on a Becton Dickinson FACScan and analyzed using CellQuest software.

Chemotaxis.

A 96-well microchemotaxis assay was employed for the studies described in this report. Ba/F3-hCCR7 cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in assay buffer (Ba/F3-hCCR7 growth medium diluted 1:10 with RPMI 1640). Recombinant mouse 6Ckine (CCL21) and MIP-3β (CCL19) (R&D Systems) were reconstituted in assay buffer and diluted 10-fold serially starting from 100 nM. Approximately 30,000 Ba/F3-hCCR7 cells were applied in 50 μl per chemotaxis filter (6.4-mm diameter; 5-μm pore size) (Neuroprobe Inc, Gaithersburg, Md.). Following a 2-h incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, cell migration was quantified using the CellTiter Glo system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Numbers of migrating cells were interpolated from standard curves.

Expression and purification of M3 protein.

Recombinant M3 (rM3) protein containing a C-terminal 6-histidine tag was produced in Spodoptera frugiperda 21 insect cells infected with a recombinant baculovirus (21) and purified by metal-affinity chromatography following standard protocols.

Assessment of biological activity of recombinant and islet-derived M3.

CCL19 or CCL21 (2.0 nM) was preincubated for 30 min at room temperature with serial dilutions of rM3. Conditioned media harvested from cultures of pancreatic islets isolated from either wild-type (WT) mice or mice bearing the M3 transgene were diluted serially and preincubated with 0.4 nM CCL21 for 30 min at room temperature. Aliquots (29 μl) were transferred to bottom wells of the microchemotaxis apparatus. Chemotaxis of Ba/F3-hCCR7 cells was determined as indicated above.

Protein analysis.

Conditioned medium from isolated islets was electrophoresed on 4 to 12% NuPage Novex Bis-Tris gels with MES SDS buffer (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) using a discontinuous buffer system (as described in Bio-Rad bulletin 2134). The polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were incubated with the anti-M3 antibody described above using the BM chemiluminescence blotting kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) as recommended.

Cell membrane preparation.

Ba/F3-hCCR7 membranes were prepared as previously described (13). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, incubated in homogenization buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 3 mM EGTA [pH 7.6]) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride for 30 min. on ice. The cells were then lysed with a Dounce homogenizer using stirrer type RZR3 polytron homogenizer (Caframo, Wiarton, Ontario, Canada) with 20 strokes at 900 rpm. The intact cells and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min. The cell membranes in the supernatant were then pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The membranes were then resuspended in glygly buffer (20 mM glycylglycine, 1 mM MgCl2, 250 mM sucrose [pH 7.2]), aliquoted, quick frozen, and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration in membrane preparations was determined using the method of Bradford (1).

[35S]GTPγ S binding.

Guanosine 5′-[γ-35S]triphospate ([35S]GTPγS) exchange was measured using a scintillation proximity assay (SPA) as previously described (5). For each assay point, membranes (4 μg/well in triplicate) were preincubated for 30 min at room temperature with 300 μg of wheat germ agglutinin-coated SPA beads (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) in SPA binding buffer (50 mM HEPES, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2, 125 mM NaCl, 0.002% NaN3, 1.0% bovine serum albumin). The beads and membranes were transferred to a 96-well Isoplate (Wallac, Gaithersburg, Md.) and incubated for 60 min at room temperature with 10 μM GDP, 10 nM of either recombinant mouse 6Ckine (CCL21) or MIP-3β (CCL19) (R&D Systems), and the indicated concentrations of M3 protein. The reactions were then incubated for a further 60 min in the presence of 0.01 nM guanosine 5′-[γ-35S]triphospate ([35S]GTPγS, triethyl ammonium salt; specific activity = 1,250 Ci/mmol; NEN, Boston, Mass.). Membrane-bound [35S]GTPγS was then measured using a Wallac Trilux 1450 microscintillation counter.

Statistical analysis.

Graphical analyses, statistical analysis and nonlinear regression analysis of the data and calculation of functional IC50 were performed using Prism 2.0c (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.). Data in the text are given as means ± standard deviations unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

M3 blocks CCL19- and CCL21-induced receptor activation.

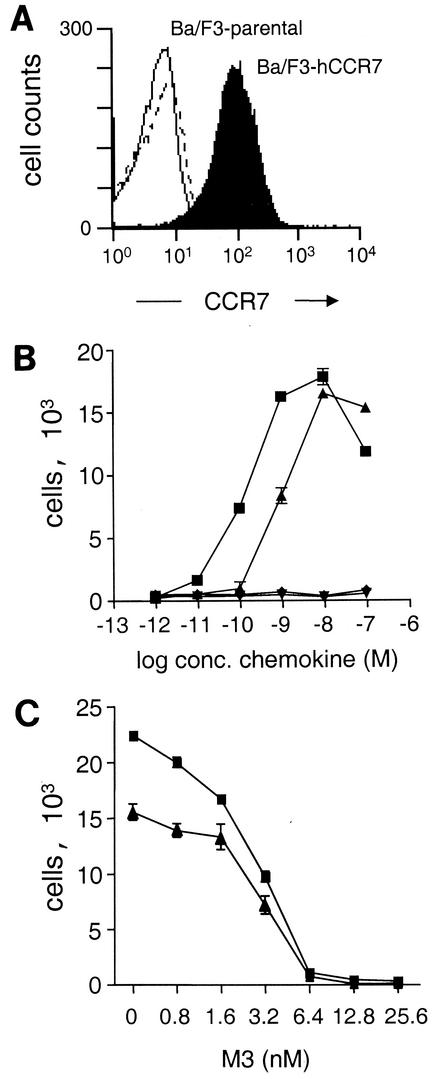

M3 has been shown to block chemokine-induced calcium flux in vitro (21, 27), but it is unknown whether it can block chemokine-induced chemotaxis. To investigate this, we tested the effect of M3 on migration of transfected cells in an in vitro chemotaxis assay. We used the CC chemokines CCL19 (also known as MIP-3β, EBI1-ligand chemokine, chemokine β-11, and Exodus-3) and CCL21 (also known as 6Ckine, secondary lymphoid chemokine, Exodus-2, and thymus-derived chemotactic agent 4) and Ba/F3 cells stably transfected with human CCR7. Expression of hCCR7 in this cell line at the cell surface was confirmed by binding assay (not shown) and flow cytometry as shown in Fig. 1A.

FIG. 1.

M3 inhibition of CCL19- and CCL21-induced chemotaxis. (A) Flow cytometry of nontransfected Ba/F3 cells (open curve), Ba/F3 stably expressing human CCR7 (filled curve), and IgG control (dashed line) using an hCCR7-specific antibody. (B) Chemotaxis of Ba/F3-hCCR7 cells toward CCL19 (▴) and CCL21 (▪) and nontransfected Ba/F3 cells toward CCL19 (▾) and CCL21 (♦). (C) CCL21 (▪) and CCL19 (▴) (each at 2.0 nM) was preincubated with the indicated concentrations of rM3 for 30 min prior to the chemotaxis assay. Data are the means and standard deviations (error bars) of triplicates. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

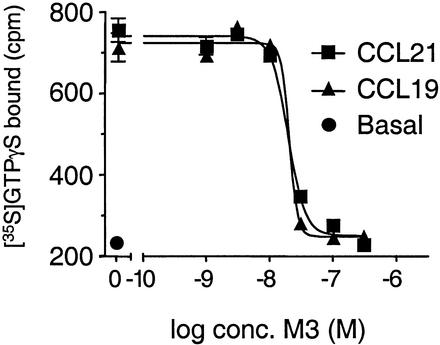

Recombinant CCL19- and CCL21-induced chemotaxis of Ba/F3-hCCR7 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). However, as shown in Fig. 1C, preincubation of either chemokine with purified rM3 efficiently blocked chemotaxis of cells. M3 blocked with equal potency the chemotactic activity of CCL19 and CCL21. The functional 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of M3 for blocking chemotaxis induced by 2.0 nM CCL21 was 2.3 ± 1.0 nM (n = 3), whereas the IC50 of M3 for blocking chemotaxis induced by 2.0 nM CCL19 was 2.6 ± 0.9 nM (n = 3) (means ± standard deviations). Interestingly, the slope of the inhibition curve had a very steep profile. We expanded on this observation using [35S]GTPγS exchange as a more biochemically defined functional assay to investigate the interaction between M3 and CCL19 and CCL21. Membranes from the Ba/F3-hCCR7 cells were incubated with [35S]GTPγS in the absence or presence of 10 nM CCL19 or CCL21 and the indicated concentrations of M3 protein (Fig. 2). As was the case in the chemotaxis experiments, receptor activation by CCL19 and CCL21 decreased in a concentration-dependent manner with increased M3 concentrations (IC50 = 19.2 ± 2.3 and 16.9 ± 2.6 nM, respectively [n = 3]). The slope of the inhibition curve was found to have Hill coefficients of >3. Hill coefficients reflect the biophysical nature of receptor-ligand interactions, where a Hill number of ∼1 implies a single binding site, Hill values of >1 indicate positive cooperative binding, and Hill values of <1 suggest negative cooperativity. Thus, our data indicate that the interaction between M3 and CCL19 and CCL21 is positively cooperative.

FIG. 2.

M3 inhibition of CCL19- and CCL21-induced [35S]GTPγS exchange in Ba/F3-hCCR7 membranes. Ba/F3-hCCR7 membranes were incubated for 60 min at room temperature in GTPγS binding buffer (as described in Materials and Methods) containing 10 μM GDP in the presence or absence of 10 nM CCL19 or CCL21 and the indicated concentrations of rM3. Following the addition of 0.3 nM [35S]GTPγS, the incubation continued for a further 60 min. Membrane-associated radioactivity was measured using SPA technology. Data represent the mean total binding and standard errors of the means (error bars) of triplicate determinations from a representative experiment (n = 3).

Generation of transgenic mice expressing M3.

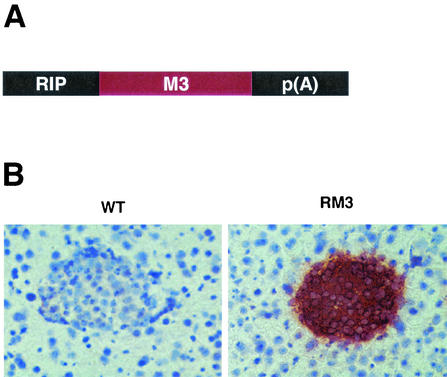

To study the biological effects of M3 in vivo, we generated transgenic mice expressing M3 in the pancreas. To this end, we constructed a transgene where the M3 gene was placed downstream of the RIP (Fig. 3A). This RIP has previously been shown to target transgene expression predominately to the pancreatic islets and the kidney (12). Eleven founders were generated from microinjection of this transgene into fertilized mouse eggs. Ten transgenic lines were established from these founders. These transgenic mice are referred to as RM3 mice. Pancreata from control and RM3 transgenic mice were initially analyzed for transgene expression by immunohistochemistry, using an anti-M3 polyclonal antibody. Seven transgenic lines showed expression of M3, and one of these was selected for further experiments (line 31). As shown in Fig. 3B, strong immunostaining could be detected in the islets of Langerhans from RM3 mice, whereas no M3 immunostaining was detected in islets from control mice. The expression of M3 in the islets of RM3 mice did not appear to compromise pancreatic function. Blood glucose levels were normal in mice from all transgenic lines indicating normal insulin production and secretion.

FIG. 3.

Generation of transgenic mice expressing M3 in pancreatic islets. (A) M3 expression is under control of the RIP; p(A) represents the rabbit β-globin polyadenylation signal. (B) Expression of M3 in the islets of RM3 transgenic mice detected by immunohistochemistry.

To examine whether constitutive expression of M3 in the pancreas had affected the development of lymphoid or nonlymphoid tissue, we examined H&E-stained sections from RM3 transgenic mice. All major organs of the RM3 mice, including pancreas, kidney, thymus, spleen, and peripheral lymph nodes, appeared normal by light microscopy (data not shown).

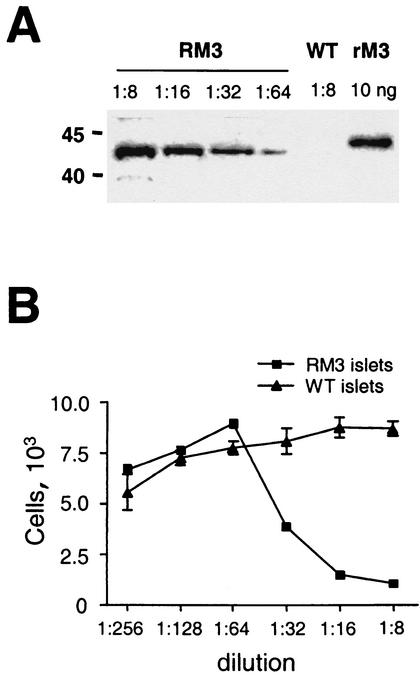

M3 from islets is secreted and prevents CCL21-induced chemotaxis in vitro.

M3 is abundantly secreted from infected cells in vitro (29). To examine whether M3 produced by the RM3 islets was secreted and biologically active, pancreatic islets were isolated by collagenase digestion and cultured for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 4A, Western blot analysis of media from RM3 islets showed an immunoreactive band of 44 kDa. No immunoreactivity was found in media from control islets. These results indicate that M3 is secreted from the cultured islets into the media. The conditioned media from transgenic and control islets were incubated with recombinant CCL21. Media from control islets did not alter the chemotaxis induced by recombinant CCL21. However, in accordance to the findings using rM3, the conditioned medium from cultured RM3 islets blocked in a concentration-dependent manner the chemotaxis of Ba/F3-hCCR7 cells (Fig. 4B). Together these results show that M3 is secreted from the RM3 islets in vitro and that M3 produced by the islets is biologically active.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of islet-derived M3. Islets were isolated by collagenase digestion and cultured in vitro. (A) Western blot showing the presence of M3 in media from cultured transgenic islets. No reactivity was detected in media from WT islets. Reactivity against rM3 is also shown. (B) Inhibition of CCL21-induced chemotaxis by islet-derived M3. Data represent the means and standard deviations (error bars) of triplicates. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments.

M3 blocks lymphoid cell recruitment induced by CCL21 in vivo.

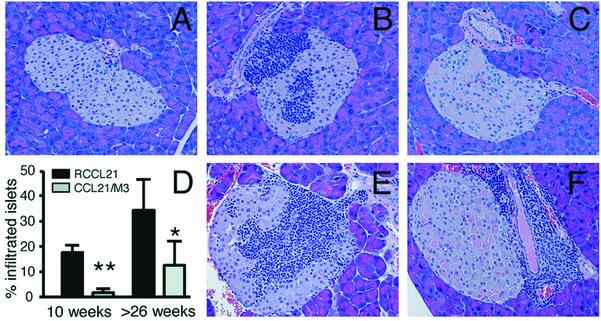

Next we tested if expression of M3 could block lymphocyte recruitment induced by CCL21 in vivo. RM3 mice were crossed with mice expressing CCL21 in pancreatic islets (RCCL21 transgenic mice). Double-transgenic mice are referred to here as CCL21/M3 mice. As described before (4, 7), ectopic expression of CCL21 in pancreatic islets leads to the development of lymphoid aggregates that resemble lymph nodes. These aggregates are composed primarily of T and B cells and few dendritic cells (4, 7). To evaluate whether expression of M3 could disrupt CCL21-induced recruitment of mononuclear cells into the pancreas, we examined H&E-stained paraffin sections of pancreata from control, single-transgenic mice and CCL21/M3 mice. Pancreata from both mature (10 weeks old) and aged mice (older than 26 weeks) were examined (40 to 170 islets were examined in each case). No infiltrates were found in islets of control or RM3 transgenic mice regardless of age (Fig. 5A). As expected, mononuclear infiltrates of various sizes were found in the pancreatic islets of RCCL21 transgenic mice. In 10-week-old RCCL21 mice, 18% ± 3% (n = 5) of the islets had infiltrates (means ± standard deviations) (Fig. 5D). These infiltrates typically contained large clusters of mononuclear cells with >50 cells per islet. A representative islet with an infiltrate is shown in Fig. 5B. In striking contrast, only 2% ± 1% of islets (n = 4) from 10-week-old mice expressing both M3 and CCL21 had infiltrates (Fig. 5D). Moreover, the infiltrates detected in the pancreas from these mice were composed of few scattered mononuclear cells, in contrast to the large infiltrates found in the RCCL21 transgenic mice (Fig. 5C). CD45 staining of pancreata from WT, RCCL21 transgenic mice and CCL21/M3 transgenic mice supported these findings (not shown). Interestingly, the proportion of infiltrated islets in both RCCL21 transgenic mice and CCL21/M3 transgenic mice increased in mice older than 26 weeks. In this age group, 34% ± 18% of the islets from RCCL21 mice had infiltrates (n = 4), whereas 14% ± 10% (n = 5) of the islets from CCL21/M3 transgenic mice had infiltrates (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, there was a very clear difference in the location of the infiltrates in the double transgenic mice compared to RCCL21 transgenic mice. Mononuclear cells occupied the center of the majority (60%) of the infiltrated RCCL21 islets (Fig. 5E). Islets from CCL21/M3 transgenic mice showed a strikingly different pattern. In 90% of the CCL21/M3 infiltrated islets the mononuclear cells accumulated near ducts or in the periphery of the islets (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that expression of M3 in pancreatic islets significantly reduce the accumulation of mononuclear cells induced by the ectopic expression of CCL21.

FIG. 5.

Characterization of cellular infiltrates in islets of RCCL21 and CCL21/M3 transgenic mice. H&E-stained paraffin sections of pancreases from WT mice (A), 10-week-old RCCL21 transgenic mice (B), and 10-week-old CCL21/M3 double-transgenic mice (C). (D) Percentage of infiltrated pancreatic islets in RCCL21 and CCL21/M3 double-transgenic mice at 10 weeks of age and at >26 weeks of age. An islet was scored as positive for infiltration if mononuclear cells could be detected either within the islet structure or in the periphery of the islet (32 **, P = 0.0018; *, P = 0.0173). (E and F) H&E-stained paraffin sections of pancreas from >26-week-old RCCL21 transgenic mice (E) and >26-week-old CCL21/M3 double-transgenic mice (F).

DISCUSSION

The M3 protein encoded by MHV-68 has been shown to bind certain chemokines with high affinity and to block chemokine-induced signal transduction in vitro (21, 27). However, there has been no definitive evidence to date that M3 blocks chemokine activity in vivo, nor has the nature of M3-chemokine interaction been defined. In this report we show for the first time that M3 can block chemotaxis induced by CCL19 and CCL21, key regulators of lymphocyte trafficking. Moreover, we show that CCL19/CCL21-M3 binding exhibits positive cooperativity.

The ability of M3 to block CCL19 and CCL21 activity is likely to have implications for MHV-68 pathogenesis. In the course of infection, MHV-68 replicates transiently at the site of infection and spreads to lymphoid tissue, where latency is established. Analysis of a recombinant MHV-68 containing a disrupted M3 gene has provided insight into a possible role of M3 in the pathogenesis of this virus (2). The M3-deficient virus replicated normally during the productive infection in the lung, and there was little difference in the initial seeding to the draining mediastinal lymph node when compared to WT virus. However, amplification of latent M3-deficient virus from splenocytes and virus-driven B-cell activation were grossly impaired. These effects of M3 deficiency were partially reversed by CD8+-T-cell depletion, suggesting that M3 chemokine blockage protects MHV-68-infected cells from elimination by CD8+ T cells in secondary lymphoid tissues.

Here we show that M3 can block the chemotactic properties of CCL19 and CCL21 in vitro. These chemokines and their receptor CCR7 are highly expressed in secondary lymphoid tissue and are thought to be essential for migration of lymphocytes and dendritic cells into lymphoid organs and their subsequent compartmentalization into specific microenvironments (6, 17). CCL21 is constitutively expressed by high endothelial venules of lymph nodes and Peyer's patches, stromal cells in the T-cell zone of secondary lymphoid organs, and lymphatic vessels (33). Lack of CCR7, CCL19, or CCL21 expression in mice is associated with defective migration of T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells into lymphoid organs (9, 16, 19, 30). Based on the findings reported here, we suggest that M3 produced by infected cells may alter migration of CCR7-expressing T, B, or dendritic cells toward local gradients of CCL19 and CCL21 and thereby disrupt immune responses. The blockage or attenuation of these responses could take place within lymphoid tissue or in the periphery. Indeed, a critical event in the host response to viral infection is the migration of antigen-loaded dendritic cells from the periphery to draining lymph nodes. Upon activation in the periphery, dendritic cells upregulate expression of CCR7 and become responsive to CCL21 (6). CCL21 is expressed by lymphatic endothelium and is thought to favor the entry of CCR7-expressing dendritic cells into the lymphatic vessels (9). By blocking the CCL21/CCR7-dependent migration of dendritic cells to the lymph node, M3 could potentially delay initiation of a specific immune response against MHV-68.

Data supporting a role for M3 in the inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking has been provided by recent studies by van Berkel and colleagues (28). In this report, it is shown that expression of M3 during MHV-68 infection in the central nervous system (CNS) reduces the relative number of lymphocytes and macrophages in the infiltrates associated with MHV-68 infection. Although a direct correlation between M3 expression and inhibition of lymphocyte and macrophage trafficking was not established, the authors demonstrated that chemokines that control trafficking of lymphocyte and macrophage are upregulated in the CNS during MHV-68 infection. Our demonstration that M3 efficiently blocks the activity of chemokines in vivo supports the contention that M3 inhibition of lymphocyte and macrophage specific chemokines is an important mechanism for immune evasion during MHV-68 infection in the CNS.

Here we have shown that when coexpressed with CCL21 in pancreatic islets, M3 effectively inhibits CCL21-induced accumulation of mononuclear cells. The number of islets infiltrated was significantly reduced in animals expressing both proteins, and more importantly, in these infiltrated islets, the mononuclear cells tended to accumulate in the periphery or in the ducts. We suggest that the ability of CCL21 to induce the formation of these infiltrates is dependent on a given effective concentration or threshold. Once this threshold is established, cells will infiltrate the islets, starting from its periphery. M3 most likely increases this threshold and thereby reduces the number of islets being infiltrated and the number of cells per infiltrate. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the infiltrating cells tend to accumulate in the periphery of the islets in older mice expressing both proteins.

Using both a chemokine-induced [35S]GTPγS exchange assay and a chemotaxis assay, we demonstrate that the CCL19/CCL21-M3 binding exhibits positive cooperativity, which is reminiscent of that recently reported by Burns et al. (3). These authors have shown that the binding of the poxvirus-encoded chemokine-binding protein vCCI (35-kDa/T1 protein) and certain chemokines is positively cooperative. The functional implication(s) of this observation in regard to the activities of M3 in vivo is unclear, but it suggests that its chemokine antagonism could occur within a very narrow dose range. These findings have implications for the understanding of the mechanisms associated with MHV-68 pathogenesis, and should be taken into consideration when evaluating the therapeutic potential of M3.

In conclusion: our results demonstrate that M3 blocks the biological activities of CCL19 and CCL21 in vitro and of CCL21 in vivo. The precipitous nature of the inhibition of CCR7 activation suggests that there is positive cooperativity in the M3-chemokine binding. Taken together, these data suggest that M3 may affect local trafficking of T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells regulated by CCL19 and CCL21. Selective disruption of leukocyte trafficking in lymphoid tissues and/or in the periphery may represent important strategies used by MHV-68 to evade immune responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Gonsiorek, D. Kinsley, M. Petro, W. Sharif, G. Vassileva, B. Wilburn, and P. Zalamea for expert technical assistance; S. Efstathiou, R. Flavell, and J. Myiazaki for reagents; and T. W. Schwartz and J. Hedrick for critical comments on the manuscript.

S.A.L. is an Irene Diamond Associate Professor of Immunology, and this work was supported in part by a grant from the Irene Diamond Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridgeman, A., P. G. Stevenson, J. P. Simas, and S. Efstathiou. 2001. A secreted chemokine binding protein encoded by murine gammaherpesvirus-68 is necessary for the establishment of a normal latent load. J. Exp. Med. 194:301-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns, J. M., D. J. Dairaghi, M. Deitz, M. Tsang, and T. J. Schall. 2002. Comprehensive mapping of poxvirus vCCI chemokine-binding protein. Expanded range of ligand interactions and unusual dissociation kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 277:2785-2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, S.-C., G. Vassileva, D. Kinsley, S. Holzmann, D. Manfra, M. T. Wiekowski, N. Romani, and S. A. Lira. 2002. Ectopic expression of the murine chemokines CCL21a and CCL21b induces the formation of lymph node-like structures in pancreas, but not skin, of transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 168:1001-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox, M. A., C. H. Jenh, W. Gonsiorek, J. Fine, S. K. Narula, P. J. Zavodny, and R. W. Hipkin. 2001. Human interferon-inducible 10-kDa protein and human interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant are allotopic ligands for human CXCR3: differential binding to receptor states. Mol. Pharmacol. 59:707-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cyster, J. G. 1999. Chemokines and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Science 286:2098-2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan, L., C. R. Reilly, Y. Luo, M. E. Dorf, and D. Lo. 2000. Cutting edge: ectopic expression of the chemokine TCA4/SLC is sufficient to trigger lymphoid neogenesis. J. Immunol. 164:3955-3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flano, E., S. M. Husain, J. T. Sample, D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 2000. Latent murine gamma-herpesvirus infection is established in activated B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages. J. Immunol. 165:1074-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster, R., A. Schubel, D. Breitfeld, E. Kremmer, I. Renner-Muller, E. Wolf, and M. Lipp. 1999. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell 99:23-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerard, C., and B. J. Rollins. 2001. Chemokines and disease. Nat. Immunol. 2:108-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotoh, M., T. Maki, T. Kiyoizumi, S. Satomi, and A. P. Monaco. 1985. An improved method for isolation of mouse pancreatic islets. Transplantation 40:437-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grewal, I. S., K. D. Grewal, F. S. Wong, D. E. Picarella, C. A. Janeway, Jr., and R. A. Flavell. 1996. Local expression of transgene encoded TNF alpha in islets prevents autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice by preventing the development of auto-reactive islet-specific T cells. J. Exp. Med. 184:1963-1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hipkin, R. W., J. Friedman, R. B. Clark, C. M. Eppler, and A. Schonbrunn. 1997. Agonist-induced desensitization, internalization, and phosphorylation of the sst2A somatostatin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 272:13869-13876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogan, B., F. Constantini, and L. Lacy. 1986. Manipulating the mouse embryo. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 15.Lalani, A. S., J. W. Barrett, and G. McFadden. 2000. Modulating chemokines: more lessons from viruses. Immunol. Today 21:100-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luther, S. A., H. L. Tang, P. L. Hyman, A. G. Farr, and J. G. Cyster. 2000. Coexpression of the chemokines ELC and SLC by T zone stromal cells and deletion of the ELC gene in the plt/plt mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12694-12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser, B., and P. Loetscher. 2001. Lymphocyte traffic control by chemokines. Nat. Immunol. 2:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy, P. M. 2001. Viral exploitation and subversion of the immune system through chemokine mimicry. Nat. Immunol. 2:116-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakano, H., T. Tamura, T. Yoshimoto, H. Yagita, M. Miyasaka, E. C. Butcher, H. Nariuchi, T. Kakiuchi, and A. Matsuzawa. 1997. Genetic defect in T lymphocyte-specific homing into peripheral lymph nodes. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okabe, M., M. Ikawa, K. Kominami, T. Nakanishi, and Y. Nishimune. 1997. Green mice as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 407:313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parry, C. M., J. P. Simas, V. P. Smith, C. A. Stewart, A. C. Minson, S. Efstathiou, and A. Alcami. 2000. A broad spectrum secreted chemokine binding protein encoded by a herpesvirus. J. Exp. Med. 191:573-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenkilde, M. M., M. Waldhoer, H. R. Luttichau, and T. W. Schwartz. 2001. Virally encoded 7TM receptors. Oncogene 20:1582-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi, D., and A. Zlotnik. 2000. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:217-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simas, J. P., and S. Efstathiou. 1998. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68: a model for the study of gammaherpesvirus pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 6:276-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevenson, P. G., and P. C. Doherty. 1998. Kinetic analysis of the specific host response to a murine gammaherpesvirus. J. Virol. 72:943-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streblow, D. N., C. Soderberg-Naucler, J. Vieira, P. Smith, E. Wakabayashi, F. Ruchti, K. Mattison, Y. Altschuler, and J. A. Nelson. 1999. The human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor US28 mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Cell 99:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Berkel, V., J. Barrett, H. L. Tiffany, D. H. Fremont, P. M. Murphy, G. McFadden, S. H. Speck, and H. I. Virgin. 2000. Identification of a gammaherpesvirus selective chemokine binding protein that inhibits chemokine action. J. Virol. 74:6741-6747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Berkel, V., B. Levine, S. B. Kapadia, J. E. Goldman, S. H. Speck, and H. W. t. Virgin. 2002. Critical role for a high-affinity chemokine-binding protein in gamma-herpesvirus-induced lethal meningitis. J. Clin. Investig. 109:905-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Berkel, V., K. Preiter, H. W. t. Virgin, and S. H. Speck. 1999. Identification and initial characterization of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 gene M3, encoding an abundantly secreted protein. J. Virol. 73:4524-4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vassileva, G., H. Soto, A. Zlotnik, H. Nakano, T. Kakiuchi, J. A. Hedrick, and S. A. Lira. 1999. The reduced expression of 6Ckine in the plt mouse results from the deletion of one of two 6Ckine genes. J. Exp. Med. 190:1183-1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Virgin, H. W. t., P. Latreille, P. Wamsley, K. Hallsworth, K. E. Weck, A. J. Dal Canto, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 71:5894-5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, T. Y., S. C. Chen, M. W. Leach, D. Manfra, B. Homey, M. Wiekowski, L. Sullivan, C. H. Jenh, S. K. Narula, S. W. Chensue, and S. A. Lira. 2000. Transgenic expression of the chemokine receptor encoded by human herpesvirus 8 induces an angioproliferative disease resembling Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Exp. Med. 191:445-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zlotnik, A., J. Morales, and J. A. Hedrick. 1999. Recent advances in chemokines and chemokine receptors. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 19:1-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]