RNA interference (RNAi) is a process of posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants, insects, and animals (4, 7, 13, 14). In vivo, RNAi is initiated by an endonuclease, DICER, that cleaves long, double-stranded RNA into 21- to 25-bp small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (2, 3, 6, 15). siRNAs are incorporated into a protein complex, the RNAi silencing complex, that recognizes and cleaves target mRNAs (12). Inhibition of viral infection and modulation of viral replication by siRNA have been demonstrated in human immunodeficiency virus and poliovirus in human cells (5, 8, 10, 11). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a positive-stranded RNA virus that has infected some 170 million worldwide. Most HCV-infected individuals develop a chronic infection that can lead to liver disease, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (1).

To test whether siRNA inhibits HCV, we made several 21-bp siRNA duplexes that were directed against different regions of the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the HCV genome. We transfected these siRNAs into 5-2 cells, a Huh-7 cell line that harbors autonomously replicating subgenomic HCV RNA (9) (Fig. 1A). The subgenomic replicon contains the firefly luciferase gene; therefore, the effect of siRNA on HCV replication was measured through the luciferase assay (9). Compared with those of mock-transfected controls, luciferase activities measured 48 h after transfection of cells with HCV siRNA 5U5 (Fig. 1B) were reduced by up to 85% in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 2A). This inhibition was not seen in cells that were transfected with the control siRNA SIN, which was targeted to Sindbis virus. Additional control siRNA duplexes, GL2 and GL3, further demonstrated the specificity of the siRNA response. Luciferase activity was reduced by 90% in cells transfected with GL2, which is homologous to the fruit fly luciferase gene. GL3, which contains three nucleotide mismatches to the gene, was unable to inhibit luciferase activity effectively (Fig. 2A). We also tested possible cellular toxicity involved in the siRNA transfections. Measurement of ATP levels within cells showed no viable change in siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2B). Finally, we tested the effect of 5U5 on HCV RNA replication in 5-2 cells by a quantitative TaqMan assay. This assay showed that 5U5 could reduce the steady-state level of the HCV RNA in a pattern similar to that obtained with the luciferase assay (data not shown).

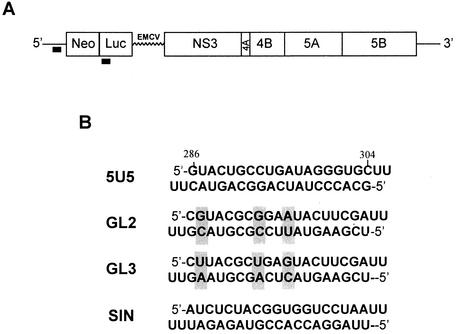

FIG. 1.

Reporter HCV replicon and siRNA duplexes. (A) The components of HCV subgenomic replicons are the HCV 5′ UTR, Neo (neomycin phosphotransferase gene), Luc (firefly luciferase reporter gene), the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosome entry site (IRES), NS3 to NS5B (HCV nonstructural genes NS3 to NS5B), and the HCV 3′ UTR. The region targeted by the siRNA is represented by a black bar. (B) The sequences of the siRNA duplexes targeting the 5′ UTR of the HCV genome (5U5) and the luciferase gene (GL2) are shown. The numbers above the 5U5 sequence represent nucleotide positions in the HCV genome. The GL2 and GL3 siRNA duplexes differ by three single-nucleotide substitutions (grey boxes). SIN targets the Sindbis virus transcription promoter and thus serves as a nonspecific control for HCV. All siRNA duplexes were synthesized and purified with a Silencer siRNA Construction Kit (Ambion).

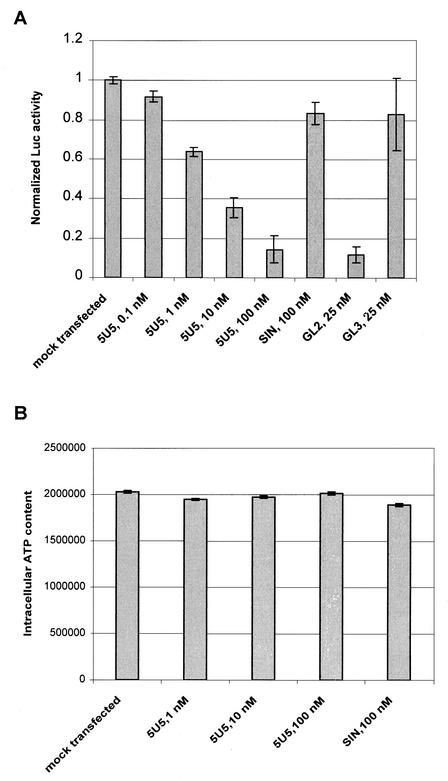

FIG. 2.

siRNA-mediated inhibition of HCV replication as measured by luciferase activity. (A) Effects of siRNA dose and sequence on luciferase activity. The indicated amounts of siRNA were transfected into 5-2 cells (5 × 104 in a 24-well plate) with 1 μl of Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). After 48 h of incubation, cell lysates were subjected to a luciferase assay (BrightGlo; Promega). Luciferase activities were normalized to that obtained by a buffer transfection. The data shown are averages of three independent transfections ± the standard deviations. (B) Effect of siRNA on cell viability. Cell viability in culture was determined by measuring the level of ATP in cells 48 h after transfection (Cell Viability Luminescent Assay; Promega). ATP levels were plotted in arbitrary luminescence units.

Our results show that a 21-bp siRNA is capable of mediating specific cleavage of target HCV RNA in human liver cells, implying that the target cell for HCV infection possesses the necessary functional components (RNAi silencing complex) of RNAi. Our observation, however, does not rule out the possibility that HCV interferes with the ability of DICER to generate siRNAs. Since HCV is very effective at persisting in the infected host, it may have evolved a mechanism(s) by which it evades the normal siRNA pathway. However, introduction of a preformed siRNA duplex would bypass the required DICER maturation in HCV-infected cells, making the standard siRNA strategy attractive. This report is a first step in demonstrating that replicating HCV RNA is amenable to siRNA-mediated degradation in human liver cells. Identification of siRNA with higher efficacy, greater stability, and targeting of siRNA is necessary to develop siRNA technology into an effective anti-HCV therapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter, M. J. 1997. Epidemiology of hepatitis C. Hepatology 3(Suppl. 1):62S-65S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein, E., A. A. Caudy, S. M. Hammond, and G. J. Hannon. 2001. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 409:363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbashir, S. M., W. Lendeckel, and T. Tuschl. 2001. RNA interference is mediated by 21- and 22-nucleotide RNAs. Genes Dev. 15:188-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fire, A. 1999. RNA-triggered gene silencing. Trends Genet. 15:358-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gitlin, L., S. Karelsky, and R. Andino. 2002. Short interfering RNA confers intracellular antiviral immunity in human cells. Nature 418:430-434. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hammond, S. M., E. Bernstein, D. Beach, and G. J. Hannon. 2000. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates posttranscriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature 404:293-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond, S. M., A. A. Caudy, and G. J. Hannon. 2001. Post-transcriptional gene silencing by double stranded RNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2:110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacque, J. M., K. Triques, and M. Stevenson. 2002. Modulation of HIV-1 replication by RNA interference. Nature 418:435-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger, N., V. Lohmann, and R. Bartenschlager. 2001. Enhancement of hepatitis C virus RNA replication by cell culture-adaptive mutations. J. Virol. 75:4614-4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, N. S., T. Dohjima, G. Bauer, H. Li, M. J. Li, A. Ehsani, P. Salvaterra, and J. Rossi. 2002. Expression of small interfering RNAs targeted against HIV-1 rev transcripts in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:500-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novina, C. D., M. F. Murray, D. M. Dykxhoorn, P. J. Beresford, J. Riess, S. K. Lee, R. G. Collman, J. Liberman, P. Shankar, and P. Sharp. 2002. siRNA-directed inhibition of HIV-1 infection. Nature Med. 8:681-686. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nykanen, A., B. Haley, and P. D. Zamore. 2001. ATP requirements and small interfering RNA structure in the RNA interference pathway. Cell 107:309-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharp, P. A. 2001. RNA interference—2001. Genes Dev. 15:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuschl, T. 2001. RNA interference and small interfering RNAs. Chem. Biochem. 2:239-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamore, P. D., T. Tuschl, P. A. Sharp, and D. P. Bartel. 2000. RNAi: double-stranded RNA directs the ATP dependent cleavage of mRNA at 21 to 23 nucleotide intervals. Cell 101:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]