Abstract

Lactoferrin is a member of the transferrin family of iron-binding glycoproteins present in milk, mucosal secretions, and the secondary granules of neutrophils. While several physiological functions have been proposed for lactoferrin, including the regulation of intestinal iron uptake, the exact function of this protein in vivo remains to be established. To directly assess the physiological functions of lactoferrin, we have generated lactoferrin knockout (LFKO−/−) mice by homologous gene targeting. LFKO−/− mice are viable and fertile, develop normally, and display no overt abnormalities. A comparison of the iron status of suckling offspring from LFKO−/− intercrosses and from wild-type (WT) intercrosses showed that lactoferrin is not essential for iron delivery during the postnatal period. Further, analysis of adult mice on a basal or a high-iron diet revealed no differences in transferrin saturation or tissue iron stores between WT and LFKO−/− mice on either diet, although the serum iron levels were slightly elevated in LFKO-/- mice on the basal diet. Consistent with the relatively normal iron status, in situ hybridization analysis demonstrated that lactoferrin is not expressed in the postnatal or adult intestine. Collectively, these results support the conclusion that lactoferrin does not play a major role in the regulation of iron homeostasis.

Lactoferrin is an 80-kDa member of the transferrin family of nonheme iron-binding glycoproteins (34). The most extensively characterized member of this family is transferrin, which functions as the major iron-binding and transport protein in serum and which is essential for iron delivery to erythrocytes and developing neuronal cells via the transferrin-transferrin receptor cycle (7, 28, 45). Despite sharing a high degree of homology at the amino acid sequence level (34) and the three-dimensional conformational level (1, 2, 4), lactoferrin differs from transferrin in many aspects, including localization and functional activity. Lactoferrin expression is first detected during murine embryonic development in the preimplantation embryo and is expressed during the latter half of gestation in the developing hematopoietic, digestive, and respiratory systems (47). In adults of many species, lactoferrin is expressed and secreted by glandular epithelial cells (27, 32). Lactoferrin is also expressed during late-stage granulopoiesis and is stored in the secondary granules of mature neutrophils, from which it is released into the circulation upon neutrophil degranulation (31). While many diverse physiological functions have been proposed for lactoferrin, including the regulation of intestinal iron uptake, antimicrobial activity, regulation of cellular growth and differentiation, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities, and protection against cancer (reviewed in references 6, 8, 23, 27, 48, and 49), the precise mechanism of action of lactoferrin in many of these processes remains poorly understood.

In particular, a long-standing controversy exists as to the role of lactoferrin in intestinal iron homeostasis. Iron is an essential element required for many metabolic functions, yet it can be toxic in excess, promoting free radical formation. Clearly, tight regulation of iron homeostasis is essential for protecting against free radical-induced cellular damage while maintaining proper cellular function. In higher organisms, iron homeostasis is regulated at the level of absorption from the diet in the proximal small intestine in response to body iron status (50). Recently, many of the genes involved in intestinal iron uptake were identified, and loss-of-function mutations of these genes in rodents have greatly enhanced the understanding of iron homeostasis at the molecular level (3). In particular, a divalent metal iron transporter (DMT-1) has been identified as a major protein involved in intestinal nonheme iron uptake at the apical surface, and loss-of-function mutations in DMT-1 have been found to result in severe iron-deficiency anemia, due in part to a primary defect in intestinal iron uptake (3, 10, 18, 19, 22). Intestinal iron homeostasis is also regulated by the product of the hemachromatosis gene, HFE, a novel major histocompatibility complex class 1-like protein that is mutated in the majority of patients with hereditary hemachromatosis (17). Mice with a targeted mutation in the HFE gene exhibit classic symptoms of hemachromatosis, including excessive intestinal iron uptake resulting in increases in serum iron levels, transferrin saturation, and liver iron stores (52). The molecular control of iron homeostasis by HFE is incompletely understood, but it has been proposed that the association of HFE and the transferrin receptor on the basolateral surface of duodenal crypt cells leads to sensing of body iron requirements, resulting in a feedback alteration in the iron absorption capacity of mature enterocytes (21, 38).

The strong iron-binding properties of lactoferrin, together with the high iron bioavailability and abundant concentration of lactoferrin in breast milk, have prompted speculation that this protein may also be involved in the delivery of iron to the neonate (23, 27). Further, it has been observed that lactoferrin is relatively resistant to proteolysis in the gastrointestinal tract (16) and that lactoferrin, but not transferrin, can deliver bound iron to human intestinal epithelial cells (14). In addition, a specific receptor for lactoferrin has been identified on the apical surface of enterocytes from many species (23), and the cloning of a human enterocyte receptor was recently reported (42). In vitro experiments demonstrating the increased uptake of iron-saturated lactoferrin in Caco-2 cells transfected with this receptor further support the view that lactoferrin is involved in intestinal iron uptake (42). However, it has also been proposed that the iron-binding properties and stability of lactoferrin are responsible for iron sequestration rather than delivery in the gastrointestinal tract, thus preventing excessive iron uptake (9). Considerable debate has persisted because of a lack of a relevant model for adequately assessing the essential physiological role of this protein in intestinal iron homeostasis.

To directly assess the functions of lactoferrin in vivo, we have generated a mouse model of lactoferrin deficiency by using gene targeting techniques. In the study described here, we show that lactoferrin is not required for intestinal iron uptake and that the iron status in the absence of lactoferrin is relatively normal, results which are inconsistent with a major role of this protein in iron homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of LFKO−/− mice.

Lactoferrin knockout (LFKO−/−) mice were generated by homologous gene targeting in embryonic stem (ES) cells. The targeting vector contains 5′ and 3′ murine lactoferrin genomic arms separated by a neomycin resistance (Neor) gene expression cassette (40). The 1.0-kb 5′ arm, carrying exons 3 and 4, part of exon 5, and intervening introns C and D, was generated by PCR amplification of 129/SvEv mouse genomic DNA with forward and reverse primers corresponding to nucleotides 208 to 238 and 571 to 600 of the murine lactoferrin cDNA, respectively (37). The 4.7-kb 3′ arm, carrying exons 9 to 13 and intervening introns, was derived from the 5′ end of a previously described 13.3-kb murine lactoferrin genomic clone (15). The targeting vector also contains the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene (30) located 5′ to the lactoferrin-homologous sequences. The vector was linearized at the 3′ end of the lactoferrin 4.7-kb fragment by using an introduced NotI restriction enzyme site and was electroporated into 129/SvEv ES cells grown in G418 and 1-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-1-β-d-arabino-furanosyl)-S-iodouracil (FIAU) selective medium. G418- and FIAU-resistant colonies were screened by Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-digested DNA with a 600-bp 5′ lactoferrin probe located outside the region of homology. Correctly targeted ES cells were used to generate chimeric mice (Lexicon Inc., The Woodlands, Houston, Tex.).

Germ line-transmitting male chimeric mice were mated with either 129/SvEv or C57BL/6 females to obtain heterozygote offspring in an inbred 129/SvEv or mixed 129/SvEv × C57BL/6 genetic background, respectively. Heterozygotes were intercrossed to obtain LFKO−/− and wild-type (WT) control mice in an inbred 129/SvEv or mixed 129/SvEv × C57BL/6 genetic background. For postnatal iron studies, WT intercrosses and LFKO−/− intercrosses were set up by using mice obtained from heterozygote mating pairs, and the resulting pups were analyzed at postnatal day 18.

Routine genotype analysis of offspring was carried out by PCR analysis of genomic tail DNA. The forward and reverse primers were as follows: WT4 (5′-GGCTCCTCGGGGGAAGAGGC-3′), HT4 (5′-GGCCACCTGCATCCCTTGAG-3′), and NEO (5′-GCATGCTCCAGACTGCCTTGGGAAA-3′). The PCR conditions used were 1 cycle of 95°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 65°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were resolved on 1.5% agarose gels. HT4-WT4 amplifies a 515-bp fragment (24-bp exon 4, 370-bp intron D, and 121 bp of exon 5) corresponding to the WT allele, whereas HT4-NEO amplifies a 575-bp fragment (24-bp exon 4, 370-bp intron D, 101 bp of exon 5, and 80 bp of the Neor gene) corresponding to the targeted allele.

Animals.

All animal research complied with National Institutes of Health and Baylor College of Medicine guidelines for experimental animals. Mice were maintained in microisolator cages in either a conventional or a barrier facility with a 12-h light-dark cycle and were fed a basal rodent chow (∼0.025% iron) ad libitum (LabDiet; PMI, Richmond, Ind.). Unless otherwise indicated, all experiments were performed with mice from the mixed genetic background (129/SvEv × C57BL/6)

Milk collection and Western immunoblot analysis.

Pups were removed from day 10 lactating females for 3 h prior to milk collection. Mice were anesthetized and injected intramuscularly with oxytocin (1 U) to stimulate milk release. Milk was collected under gentle vacuum by using tubing fitted over the nipple. Total milk protein (5 to 30 μg) was resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to enhanced chemiluminescence Hybond membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.). The membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline-0.5% Tween 20 (TBST) containing 10% nonfat dry milk. The membranes were rinsed in TBST and incubated in TBST-1% nonfat dry milk containing rabbit anti-mouse lactoferrin antisera (1:25,000) (kindly provided by Christina Teng, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Research Triangle Park, N.C.) or rabbit anti-mouse transferrin antisera (1:10,000) (Inter-Cell, Hopewell, N.J.) for 1 h at room temperature. The filters were washed in TBST and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in TBST-1% nonfat dry milk containing horseradish peroxidase-labeled donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody (1:25,000) (Amersham Biosciences). The filters were washed in TBST, and the signal was detected by using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection method. Quantitation of relative levels of milk lactoferrin and transferrin was performed by comparison to the levels of purified recombinant murine lactoferrin (46) or mouse transferrin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) standards by using densitometric scanning and ImageQuant software (version 5.2; Amersham Biosciences).

Iron diet studies.

Adult mice (8 to 10 weeks old) were placed on a basal iron (TD 91014) or a high-iron (TD 91013) diet for 2 weeks. Diets were formulated by Harlan Tekland (Madison, Wis.). Basal iron diets consisted of Purina 5001 containing 0.02% (wt/wt) iron and 0.01% (wt/wt) butylated hydroxytoluene. High-iron diets consisted of Purina 5001 supplemented with 2% (wt/wt) carbonyl iron and 0.01% (wt/wt) butylated hydroxytoluene.

Hematological measurements.

Heparinized blood was obtained by retro-orbital phlebotomy under anesthesia. Red blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and mean corpuscular volume were determined by using an automated H1 Technicon system.

Serum iron measurements.

Blood was obtained by retro-orbital phlebotomy under anesthesia. Serum was stored at −20°C until use. The serum iron level and the unsaturated iron-binding capacity (UIBC) were determined colorimetrically by using a kit from Sigma (no. 565) with slight modifications for use in a microtiter plate assay (40 μl of serum per assay). The total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) was calculated by adding the serum iron level and the UIBC. Transferrin saturation was calculated as (serum iron level/TIBC) × 100.

Tissue nonheme iron measurements.

Liver and spleen samples were dried and digested in concentrated nitric acid. Tissue nonheme iron concentrations (micrograms of iron per gram [dry weight] of tissue) were determined spectrophotometrically by using a Beckman Synchron LX 20 system (Department of Laboratory Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle).

In situ hybridization.

Uterine or duodenal tissues were fixed in Bouin fixative and processed for paraffin sectioning (6 μm). Sections were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol, placed in proteinase K solution (20 mg/ml) for 7 min at 37°C, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min. Sections were rinsed briefly in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated H2O and incubated in 0.25% acetic anhydride-0.1 M triethanolamine. Sections were dehydrated and hybridized overnight at 55°C with a 35S-labeled antisense murine lactoferrin cDNA probe (nucleotides 2008 to 2223) (37). Sections were washed in 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) (55°C) and 2× SSC (65°C) containing 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol-10 mM sodium thiosulfate, followed by RNase (20 μg/ml) incubation at 37°C for 30 min. Washing after RNase treatment was done for 15 min in 1× SSC-10 mM sodium thiosulfate (65°C) followed by 0.1× SSC-10 mM sodium thiosulfate (65°C). Dehydration was performed through a graded series of ethanol containing 300 mM ammonium acetate. The samples were air dried and dipped in autoradiography emulsion type NTB-2, and images were acquired by using dark-field microscopy (Zeiss Axioskop; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, N.Y.).

Histochemical and immunohistochemical analyses.

The proximal small intestine (duodenum) was fixed overnight in Bouin fixative, washed in 70% ethanol, and processed for paraffin sectioning. Intestinal cross sections (5 μm) were mounted on microscope slides, deparaffinized, and rehydrated. The specificity of the histological and immunostaining methods used has been described previously (13, 51). Alcian blue-nuclear fast red staining was used to detect goblet cells. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed by using antisera specific for enterocytes (intestinal fatty acid-binding protein [IFABP]), goblet cells (lysozyme), and enteroendocrine cells (serotonin). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched in 3% hydrogen peroxide-methanol. For lysozyme detection, antigen retrieval was carried out prior to incubation with the primary antibody by incubating sections with 0.05% trypsin for 25 min at 37°C. Sections were incubated in blocking solution (10% normal goat serum in PBS) and then incubated with one of the following primary antisera: rabbit anti-human IFABP (1:1,000; Hycult Biotechnology), rabbit antiserotonin (1:4,000; Diasorin, Inc.), or rabbit anti-human lysozyme (1:100; Novocastra). Sections were washed in PBS and incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit;1:100, 1:500, and 1:2,000 for lysozyme, IFAPB, and serotonin staining, respectively). Sections were washed in PBS, and immunoreactivity was detected by using streptavidin-peroxidase (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, Calif.) and 5-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride as the substrate chromogen (Sigma). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin or a combination of hematoxylin and eosin, dehydrated and cleared in xylene, and placed on coverslips for bright-field microscopy.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between groups were examined by using Student's t test for the equality of means, with a P value of <0.05 being considered statistically significant. When the F values for Levene's test for the equality of variances were significant, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the level of significance. Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS (Chicago, Ill.) software (version 10).

RESULTS

Generation of LFKO−/− mice.

Mice deficient in lactoferrin were generated by homologous gene targeting in ES cells; in this procedure, part of exon 5, exons 6 to 9, and intervening introns of the lactoferrin gene were replaced with a neomycin resistance gene cassette (Fig. 1A). This targeting strategy disrupts the lactoferrin gene in the first iron-binding domain. Correctly targeted ES cells were used to generate chimeric mice. Germ line-transmitting male chimeric mice were mated with C57BL/6 female mice, and the resulting heterozygotes were intercrossed. Southern blot analysis of genomic tail DNA from these offspring confirmed the generation of homozygote mice (Fig. 1B). DNA digestion with EcoRI and hybridization with a 32P-labeled DNA probe carrying exon 2 revealed radioactive bands at 10.6 kb, representing the wild-type allele, and at 6.6 kb, corresponding to the targeted allele (Fig. 1B). Routine genotyping of mice was carried out by PCR amplification (Fig. 1C) with primers specific for the lactoferrin and neomycin genes.

FIG. 1.

Generation of LFKO−/− mice. (A) Targeting strategy. A schematic diagram of the targeting construct is shown in the top panel. Numbered boxes represent exons. The wild-type allele and the targeted allele are shown in the middle and bottom panels, respectively. After homologous recombination, the targeted allele contains an additional EcoRI site introduced with the neomycin resistance gene cassette. A 5′ probe located outside the region of homology detects a 10.6-kb fragment in the wild-type allele and a 6.6-kb fragment in the targeted allele. HSV-TK, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. (B) Genotype identification by Southern blot analysis. Genomic tail DNA from offspring from heterozygote intercrosses was digested with EcoRI and probed with a 5′ probe located outside the region of homology. In WT mice, a single radioactive band at 10.6 kb, corresponding to two normal alleles, is detected (third lane). In LFKO+/− mice, two hybridizing bands, representing the 10.6-kb normal allele and the 6.6-kb targeted allele, are detected (second lane). LFKO−/− mice are detected by the presence of a single radioactive band at 6.6 kb, corresponding to two targeted alleles (first and fourth lanes). (C) Genotype identification by PCR analysis. A PCR product of 515 bp represents the WT allele, whereas a product of 575 bp represents the targeted allele. WT mice (first and second lanes), LFKO+/− mice (third lane), and LFKO−/− mice (fourth lane) are identified. (D) Western immunoblot analysis of mouse milk samples. Western immunoblot analysis was performed by using specific antisera directed against murine lactoferrin. A single immunoreactive band migrating at the size expected for lactoferrin is detected in the milk samples from WT mice (first lane) and LFKO+/− mice (second lane) but not in the milk samples from LFKO−/− mice (third lane).

Two independent clones contributed to germ line transmission, and homozygote LFKO−/− mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio. To confirm that we had successfully abolished the expression of the lactoferrin protein, we performed Western immunoblot analysis on milk samples by using polyclonal antisera directed against murine lactoferrin (Fig. 1D). A single immunoreactive band migrating at the size expected for lactoferrin protein was detected in the milk from both WT and LFKO+/− mice. No lactoferrin protein was detected in the milk of LFKO−/− mice, indicating that the expression of the lactoferrin protein had been abolished. Male and female LFKO−/− mice are fertile, develop normally, and display no gross morphological abnormalities.

Lactoferrin is not required for postnatal intestinal iron uptake.

Maternal milk provides a unique source of lactoferrin to suckling pups and has been postulated to play a role in intestinal iron delivery (23). To test this hypothesis, serum and tissue iron indices were measured in postnatal day 18 LFKO−/− and WT pups derived from LFKO−/− intercrosses (no maternal or endogenous lactoferrin) or from WT intercrosses (maternal and endogenous lactoferrin). The results of this analysis are outlined in Tables 1 and 2. Both serum iron levels and transferrin saturation were elevated in LFKO−/− pups, although only transferrin saturation (69.7% ± 2.4% versus 54.5% ± 6.3%) reached statistical significance (P = 0.048). The TIBC was significantly lower in LFKO−/− mice (322.5 ± 8.3 μg/dl versus 361.8 ± 7.6 μg/dl) (P = 0.006) (Table 1). Significant increases in liver iron stores (181.4 ± 6.2 μg/g versus 129.4 ± 5.4 μg/g) (P < 0.001) were also observed in the absence of lactoferrin, while spleen iron stores were significantly decreased (359.5 ± 16.9 μg/g versus 481.8 ± 33.6 μg/g) (P = 0.001) (Table 2). The resistance of the spleen to iron loading was previously reported (33, 52), although the significance of the decreased iron stores in the LFKO−/− pups remains to be elucidated. Erythroid parameters were similar for the two genotype groups (Table 3), indicating that a null allele of lactoferrin does not result in anemia.

TABLE 1.

Serum iron indices in LFKO−/− pups (postnatal day 18)a

| Mice | n | Value (μg/dl) for:

|

Transferrin saturation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum iron | TIBC | |||

| WT | 13 | 195.5 ± 22 | 361.8 ± 7.6 | 54.5 ± 6.3 |

| LFKO−/− | 22 | 223.7 ± 8.5 | 322.5 ± 8.3b | 69.7 ± 2.4b |

WT and LFKO−/− mating pairs were fed a basal iron diet ad libitum. Pups were weaned at postnatal day 18. Values are means and SEMs.

The value was significantly different (P < 0.05) from that for the WT mice.

TABLE 2.

Tissue iron stores in LFKO−/− pups (postnatal day 18)a

| Mice | n | Iron level (μg/g) in:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Spleen | ||

| WT | 8 | 129.4 ± 5.4 | 481.8 ± 33.6 |

| LFKO | 15 | 181.4 ± 6.2b | 359.5 ± 16.9b |

WT and LFKO−/− mating pairs were fed a basal iron diet ad libitum. Pups were weaned at postnatal day 18. Values are means and SEMs.

The value was significantly different (P < 0.05) from that for the WT mice.

TABLE 3.

Erythroid measurements in LFKO−/− pups (postnatal day 18)a

| Mice | n | RBC (106/μl) | HGB (g/dl) | HCT (%) | MCV (fl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 8 | 5.68 ± 0.2 | 9.64 ± 0.26 | 31.21 ± 0.76 | 55.08 ± 0.64 |

| LFKO | 7 | 6.09 ± 0.33 | 9.8 ± 0.46 | 32.13 ± 1.33 | 53.04 ± 0.93 |

RBC, red blood cells; HGB, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; values are means and SEMs.

It was shown previously that genetic background markedly influences iron parameters in mice (12, 25, 41). To determine whether the postnatal iron overloading observed in LFKO−/− pups in the mixed genetic background was due to 129/Sv alleles segregating with the targeted lactoferrin mutation (39), a further analysis of iron in the liver, as the primary target tissue of iron overload, was carried out in an inbred 129/SvEv genetic background. This genetic background has been reported to be more susceptible to iron overload than the mixed 129/SvEv × C57BL/6 genetic background (29). A comparison of offspring from 129/SvEv LFKO−/− intercrosses with those from 129/SvEv WT intercrosses showed that the elimination of lactoferrin did not cause any significant difference in hepatic iron content in this inbred strain; the levels of iron in the liver were 277.8 ± 21.1 and 309.8 ± 25.9 μg/g, respectively, in 129/SvEv WT and 129/SvEv LFKO−/− mice given a basal diet ad libitum and weaned at postnatal day 18 (eight mice per group). These results suggest that the 129/SvEv gene(s) in close proximity to the targeted lactoferrin allele may contribute to the iron overload observed in LFKO−/− mice in the mixed genetic background (Tables 1 and 2). Taken together, these results indicate that lactoferrin does not play a major role in iron homeostasis in postnatal pups.

Normal development of the intestinal tract in the absence of lactoferrin.

The crypt and villus architecture of the small intestine is composed of four principal cell lineages, absorptive enterocytes (which constitute ∼80% of the villus cells), mucus-producing goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells, and crypt-associated Paneth cells (11). To determine whether intestinal cell development was normal in the absence of lactoferrin, duodenal sections from 18-day-old LFKO−/− and WT pups derived from LFKO−/− and WT intercrosses were analyzed by using specific markers for all four intestinal cell lineages. The results of this analysis are outlined in Fig. 2. No differences were observed in the immunohistochemical detection of IFABP (enterocytes), serotonin (enteroendocrine cells), lysozyme (Paneth cells), or Alcian blue staining (goblet cells). Hence, the absence of lactoferrin did not perturb the development of any of the four cell lineages, suggesting that lactoferrin is not required for intestinal morphogenesis.

FIG. 2.

Intestinal cell morphogenesis in LFKO−/− mice. Intestinal sections from WT mice (left panels) and LFKO−/− mice (right panels) were analyzed at postnatal day 18. Sections of the proximal duodenum were stained as follows. (A and B) Anti-human IFABP; specificity, enterocytes. Staining (brown) is confined to the villus enterocytes. Arrows indicate negatively stained goblet cells. (C and D) Antiserotonin; specificity, enteroendocrine cells. Arrowheads indicate representative stained cells (brown). (E and F) Anti-human lysozyme; specificity, Paneth cells. Staining (brown) is confined to the crypts. (G and H) Alcian blue; specificity, goblet cells. Positive cells (blue) are detected in the villi. No staining was observed in control sections incubated with nonimmune serum in place of primary antibody (data not shown). Stained sections are representative of at least seven mice analyzed for each genotype group. Magnifications: A to D, ×200; E to H, ×320. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Murine milk contains high levels of both lactoferrin and transferrin.

Previous studies showed that transferrin is the major iron-binding protein in mouse milk and that lactoferrin is present in lower quantities (26, 35). To examine the relative levels of lactoferrin and transferrin in the milk of our mouse strain, quantitative Western immunoblot analysis was performed on milk obtained from three WT females by using antisera directed against murine lactoferrin or murine transferrin. The results of this analysis demonstrated that lactoferrin and transferrin are both present at high levels in WT mouse milk (data not shown). However, transferrin levels are ∼15-fold higher than lactoferrin levels (4 ± 0.61 mg/ml versus 0.27 ± 0.05 mg/ml). Hence, transferrin and lactoferrin may have iron-dependent redundant functions in the small intestine during the suckling period.

Normal iron homeostasis in adult mice in the absence of lactoferrin.

To further examine the effect of a null allele of lactoferrin on adult mouse iron homeostasis, 8- to 10-week-old LFKO−/− and WT mice obtained from heterozygote intercrosses were maintained on a basal diet (0.02% iron) or placed on a high-iron diet (2% iron) for 2 weeks, after which iron indices were measured. The results of this analysis are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Serum iron indices were slightly, although significantly, higher in LFKO−/− mice than in WT mice on the basal diet (203.6 ± 8.6 μg/dl versus 170.5 ± 12.8 μg/dl) (P = 0.043). However, no significant differences in transferrin saturation, TIBC, or tissue iron stores were observed between LFKO−/− and WT mice on this diet. Further, there were no significant differences in serum iron indices, TIBC, transferrin saturation, or tissue iron stores between LFKO−/− and WT mice placed on a high-iron diet for 2 weeks. These results further argue that lactoferrin is not essential for normal iron homeostasis.

TABLE 4.

Serum iron indices in adult mice on basal and high-iron dietsa

| Mice | Diet (% iron) | Serum iron level

|

TIBC

|

Transferrin saturation

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | μg/dl | n | μg/dl | n | % | ||

| WT | 0.02 | 6 | 170.5 ± 12.8 | 6 | 398.0 ± 14.3 | 6 | 43.0 ± 3.1 |

| LFKO−/− | 0.02 | 9 | 203.6 ± 8.6b | 8 | 425.3 ± 7.6 | 8 | 47.2 ± 1.6 |

| WT | 2.0 | 5 | 240.1 ± 8.4 | 5 | 297.7 ± 24.1 | 5 | 82.0 ± 4.6 |

| LFKO−/− | 2.0 | 7 | 231.4 ± 13 | 6 | 274.0 ± 19.7 | 6 | 84.9 ± 1.9 |

Adult WT and LFKO−/− mice from heterozygote intercrosses were maintained on a basal (0.02% iron) or high-iron (2.0% iron) diet ad libitum for 2 weeks. n, number of mice tested. Values are means and SEMs.

The value was significantly different (P < 0.05) from that for the WT mice.

TABLE 5.

Tissue iron stores in adult mice on basal and high-iron dietsa

| Mice | Diet (% iron) | n | Iron level (μg/g) in:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Spleen | |||

| WT | 0.02 | 6 | 231.8 ± 16.6 | 1,339.2 ± 200.4 |

| LFKO−/− | 0.02 | 9 | 234.3 ± 25 | 1,472.9 ± 189 |

| WT | 2.0 | 5 | 2,016.6 ± 155.8 | 2,656.8 ± 429.2 |

| LFKO−/− | 2.0 | 8 | 1,996.4 ± 138.9 | 2,415.8 ± 187.6 |

Adult WT and LFKO−/− mice from heterozygote intercrosses were maintained on a basal (0.02% iron) or high-iron (2.0% iron) diet ad libitum for 2 weeks. n, number of mice tested. Values are means and SEMs.

Lactoferrin mRNA is not expressed in the postnatal or adult duodenum in mice.

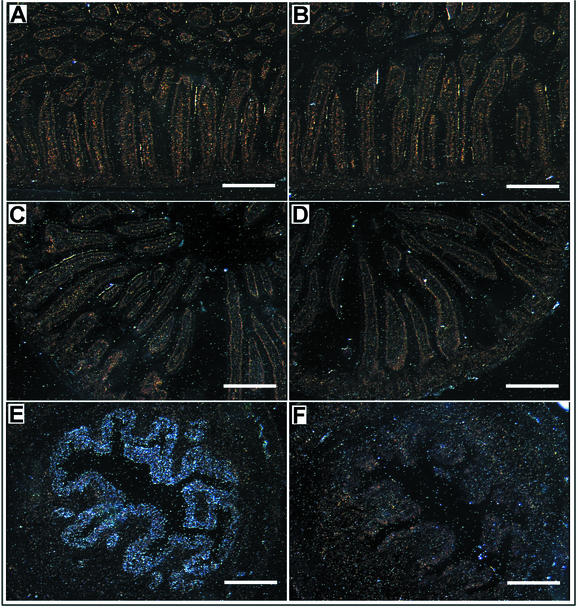

To examine whether lactoferrin is expressed endogenously at the site of intestinal iron absorption from the diet, in situ hybridization was performed on duodenal sections by using a 35S-labeled lactoferrin antisense riboprobe. The results of this analysis are shown in Fig. 3. Specific staining was observed in the glandular and luminal epithelia of an estrogen-primed uterus, which was used as a positive control for lactoferrin mRNA expression (Fig. 3E). However, no staining was observed in either 18-day-old (Fig. 3A) or adult (Fig. 3C) small intestine. Collectively, these results do not support an essential role for lactoferrin in intestinal iron homeostasis during postnatal or adult development.

FIG. 3.

In situ hybridization analysis of lactoferrin expression in mouse tissues. Sections were incubated with a specific 35S-labeled antisense (A, C, and E) or sense (B, D, and F) murine lactoferrin probe. Dark-field illumination shows postnatal day 18 duodenum (A and B), adult duodenum (C and D), and estrogen-primed uterus (E and F). Magnification, ×100. Scale bars, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we generated a mouse model of lactoferrin deficiency to determine the essential physiological roles of lactoferrin. We show that LFKO−/− mice are viable and fertile and display no overt abnormal phenotype. These findings were surprising in light of the widespread expression of lactoferrin during pre- and postnatal development (27, 31, 32, 47), where it has been implicated in many diverse physiological functions, from iron homeostasis to antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic activities (6, 8, 23, 27, 36, 48, 49).

Intestinal cell development is normal in the absence of lactoferrin, indicating that this protein is not required for intestinal morphogenesis. While mild iron overloading was observed in LFKO−/− pups derived from a mixed 129/SvEv × C57BL/6 genetic background, these findings were not reproducible in an isogenic 129/SvEv genetic background. LFKO−/− mice derived from heterozygote intercrosses in the mixed genetic background contain 129/Sv genomic sequences segregating with the targeted locus, whereas WT control mice derived from these intercrosses contain C57BL/6 DNA at these loci (39). Further, it was reported previously that strain 129 mice are susceptible to iron loading, whereas C57BL/6 mice are relatively resistant (12, 20, 25, 29). Hence, these results suggest that other 129/Sv genes involved in iron metabolism may be linked to the targeted lactoferrin genetic locus and may contribute to the iron overload observed in LFKO−/− pups in the mixed genetic background. In this regard, transferrin and ceruloplasmin are located on chromosome 9 in the vicinity of the lactoferrin locus and may contribute to the altered iron status observed in LFKO−/− pups in the mixed genetic background (5, 43).

As lactoferrin is not expressed endogenously in the duodenum of WT mice at postnatal day 18, the functional role of this protein in the intestine during the postnatal period is likely imparted by maternal milk-derived lactoferrin. While lactoferrin is present in substantial quantities in murine milk, transferrin is the primary iron-binding protein in the milk of this species (26). The possibility that transferrin functions redundantly with lactoferrin to limit iron uptake at the intestinal surface during the suckling period is intriguing. Consistent with the lack of lactoferrin expression in the WT adult mouse duodenum, we did not detect any major differences in iron indices between WT and LFKO−/− mice maintained on either a basal or a high-iron diet. Taken together, these results do not support an essential nonredundant role of lactoferrin in intestinal iron homeostasis.

A human intestinal receptor for lactoferrin was recently shown to be identical to a novel member of the lectin family, intelectin (42, 44). Intelectin is widely expressed in many tissues, including the small intestine, colon, heart, and thymus, and has been proposed to play a role in the innate immune response to microbes containing the bacterium-specific carbohydrate galactofuranose (24, 44). Although increased iron uptake from human lactoferrin was observed in vitro in Caco-2 cells transfected with a human lactoferrin receptor (intelectin) (42), the restriction of the expression of the mouse receptor homologue to the Paneth cell lineage in the intestine (24) argues against a role in iron delivery and suggests that the primary role of this receptor may be in host defense against microbial infection, not in intestinal iron absorption.

In summary, we showed that lactoferrin is not required for intestinal iron uptake and that relatively normal iron parameters were observed in LFKO−/− mice. Further, no overt phenotypic abnormalities were observed under normal physiological conditions. The availability of LFKO−/− mice will now provide researchers with an important genetic model for assessing the essential roles of lactoferrin in host protection under conditions of microbial, inflammatory, and carcinogenic challenges.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mario Lopez and Victoria Yao for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by a grant from USDA/CRIS (FYOO 6250 5100 039) and Agennix Inc., Houston, Tex., to O.M.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, B. F., H. M. Baker, E. J. Dodson, G. E. Norris, S. V. Rumball, J. M. Waters, and E. N. Baker. 1987. Structure of human lactoferrin at 3.2-A resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:1769-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, B. F., H. M. Baker, G. E. Norris, D. W. Rice, and E. N. Baker. 1989. Structure of human lactoferrin: crystallographic structure analysis and refinement at 2.8 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 209:711-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews, N. C. 2000. Iron homeostasis: insights from genetics and animal models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 1:208-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey, S., R. W. Evans, R. C. Garratt, B. Gorinsky, S. Hasnain, C. Horsburgh, H. Jhoti, P. F. Lindley, A. Mydin, R. Sarra, et al. 1988. Molecular structure of serum transferrin at 3.3-A resolution. Biochemistry 27:5804-5812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranov, V. S., A. L. Schwartzman, V. N. Gorbunova, V. S. Gaitskhoki, N. B. Rubtsov, N. A. Timchenko, and S. A. Neifakh. 1987. Chromosomal localization of ceruloplasmin and transferrin genes in laboratory rats, mice and in man by hybridization with specific DNA probes. Chromosoma 96:60-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baveye, S., E. Elass, J. Mazurier, G. Spik, and D. Legrand. 1999. Lactoferrin: a multifunctional glycoprotein involved in the modulation of the inflammatory process. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 37:281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernstein, S. E. 1987. Hereditary hypotransferrinemia with hemosiderosis, a murine disorder resembling human atransferrinemia. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 110:690-705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brock, J. 1995. Lactoferrin: a multifunctional immunoregulatory protein? Immunol. Today 16:417-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock, J. H. 1980. Lactoferrin in human milk: its role in iron absorption and protection against enteric infection in the newborn infant. Arch. Dis. Child. 55:417-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canonne-Hergaux, F., S. Gruenheid, P. Ponka, and P. Gros. 1999. Cellular and subcellular localization of the Nramp2 iron transporter in the intestinal brush border and regulation by dietary iron. Blood 93:4406-4417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng, H., and C. P. Leblond. 1974. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. V. Unitarian theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am. J. Anat. 141:537-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clothier, B., S. Robinson, R. A. Akhtar, J. E. Francis, T. J. Peters, K. Raja, and A. G. Smith. 2000. Genetic variation of basal iron status, ferritin and iron regulatory protein in mice: potential for modulation of oxidative stress. Biochem. Pharmacol. 59:115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohn, S. M., T. C. Simon, K. A. Roth, E. H. Birkenmeier, and J. I. Gordon. 1992. Use of transgenic mice to map cis-acting elements in the intestinal fatty acid binding protein gene (Fabpi) that control its cell lineage-specific and regional patterns of expression along the duodenal-colonic and crypt-villus axes of the gut epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 119:27-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox, T. M., J. Mazurier, G. Spik, J. Montreuil, and T. J. Peters. 1979. Iron binding proteins and influx of iron across the duodenal brush border. Evidence for specific lactotransferrin receptors in the human intestine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 588:120-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham, G. A., D. R. Headon, and O. M. Conneely. 1992. Structural organization of the mouse lactoferrin gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 189:1725-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson, L. A., and B. Lonnerdal. 1987. Persistence of human milk proteins in the breast-fed infant. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 76:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feder, J. N., A. Gnirke, W. Thomas, Z. Tsuchihashi, D. A. Ruddy, A. Basava, F. Dormishian, R. Domingo, Jr., M. C. Ellis, A. Fullan, L. M. Hinton, N. L. Jones, B. E. Kimmel, G. S. Kronmal, P. Lauer, V. K. Lee, D. B. Loeb, F. A. Mapa, E. McClelland, N. C. Meyer, G. A. Mintier, N. Moeller, T. Moore, E. Morikang, R. K. Wolff, et al. 1996. A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Nat. Genet. 13:399-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleming, M. D., M. A. Romano, M. A. Su, L. M. Garrick, M. D. Garrick, and N. C. Andrews. 1998. Nramp2 is mutated in the anemic Belgrade (b) rat: evidence of a role for Nramp2 in endosomal iron transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1148-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming, M. D., C. C. Trenor III, M. A. Su, D. Foernzler, D. R. Beier, W. F. Dietrich, and N. C. Andrews. 1997. Microcytic anaemia mice have a mutation in Nramp2, a candidate iron transporter gene. Nat. Genet. 16:383-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming, R. E., C. C. Holden, S. Tomatsu, A. Waheed, E. M. Brunt, R. S. Britton, B. R. Bacon, D. C. Roopenian, and W. S. Sly. 2001. Mouse strain differences determine severity of iron accumulation in Hfe knockout model of hereditary hemochromatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2707-2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming, R. E., and W. S. Sly. 2002. Mechanisms of iron accumulation in hereditary hemochromatosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64:663-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunshin, H., B. Mackenzie, U. V. Berger, Y. Gunshin, M. F. Romero, W. F. Boron, S. Nussberger, J. L. Gollan, and M. A. Hediger. 1997. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature 388:482-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iyer, S., and B. Lonnerdal. 1993. Lactoferrin, lactoferrin receptors and iron metabolism. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 47:232-241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komiya, T., Y. Tanigawa, and S. Hirohashi. 1998. Cloning of the novel gene intelectin, which is expressed in intestinal Paneth cells in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251:759-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leboeuf, R. C., D. Tolson, and J. W. Heinecke. 1995. Dissociation between tissue iron concentrations and transferrin saturation among inbred mouse strains. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 126:128-136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, E. Y., M. H. Barcellos-Hoff, L. H. Chen, G. Parry, and M. J. Bissell. 1987. Transferrin is a major mouse milk protein and is synthesized by mammary epithelial cells. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. 23:221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levay, P. F., and M. Viljoen. 1995. Lactoferrin: a general review. Haematologica 80:252-267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy, J. E., O. Jin, Y. Fujiwara, F. Kuo, and N. C. Andrews. 1999. Transferrin receptor is necessary for development of erythrocytes and the nervous system. Nat. Genet. 21:396-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy, J. E., L. K. Montross, D. E. Cohen, M. D. Fleming, and N. C. Andrews. 1999. The C282Y mutation causing hereditary hemochromatosis does not produce a null allele. Blood 94:9-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansour, S. L., K. R. Thomas, and M. R. Capecchi. 1988. Disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 in mouse embryo-derived stem cells: a general strategy for targeting mutations to non-selectable genes. Nature 336:348-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masson, P. L., J. F. Heremans, and E. Schonne. 1969. Lactoferrin, an iron-binding protein in neutrophilic leukocytes. J. Exp. Med. 130:643-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masson, P. L., Heremans, J. F., and C. Dive. 1966. An iron-binding protein common to many external secretions. Clin. Chim. Acta 14:735-739. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLaren, G. D. 1989. Reticuloendothelial iron stores and hereditary hemochromatosis: a paradox. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 113:137-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metz-Boutigue, M. H., J. Jolles, J. Mazurier, F. Schoentgen, D. Legrand, G. Spik, J. Montreuil, and P. Jolles. 1984. Human lactotransferrin: amino acid sequence and structural comparisons with other transferrins. Eur. J. Biochem. 145:659-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neville, M. C., K. Chatfield, L. Hansen, A. Lewis, J. Monks, J. Nuijens, M. Ollivier-Bousquet, F. Schanbacher, V. Sawicki, and P. Zhang. 1998. Lactoferrin secretion into mouse milk. Development of secretory activity, the localization of lactoferrin in the secretory pathway, and interactions of lactoferrin with milk iron. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 443:141-153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nuijens, J. H., P. H. van Berkel, and F. L. Schanbacher. 1996. Structure and biological actions of lactoferrin. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 1:285-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pentecost, B. T., and C. T. Teng. 1987. Lactotransferrin is the major estrogen inducible protein of mouse uterine secretions. J. Biol. Chem. 262:10134-10139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pietrangelo, A. 2002. Physiology of iron transport and the hemochromatosis gene. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 282:G403-G414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sigmund, C. D. 2000. Viewpoint: are studies in genetically altered mice out of control? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20:1425-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soriano, P., C. Montgomery, R. Geske, and A. Bradley. 1991. Targeted disruption of the c-src proto-oncogene leads to osteopetrosis in mice. Cell 64:693-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sproule, T. J., E. C. Jazwinska, R. S. Britton, B. R. Bacon, R. E. Fleming, W. S. Sly, and D. C. Roopenian. 2001. Naturally variant autosomal and sex-linked loci determine the severity of iron overload in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5170-5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki, Y. A., K. Shin, and B. Lonnerdal. 2001. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a human intestinal lactoferrin receptor. Biochemistry 40:15771-15779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teng, C. T., B. T. Pentecost, A. Marshall, A. Solomon, B. H. Bowman, P. A. Lalley, and S. L. Naylor. 1987. Assignment of the lactotransferrin gene to human chromosome 3 and to mouse chromosome 9. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 13:689-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuji, S., J. Uehori, M. Matsumoto, Y. Suzuki, A. Matsuhisa, K. Toyoshima, and T. Seya. 2001. Human intelectin is a novel soluble lectin that recognizes galactofuranose in carbohydrate chains of bacterial cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23456-23463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Renswoude, J., K. R. Bridges, J. B. Harford, and R. D. Klausner. 1982. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and the uptake of Fe in K562 cells: identification of a nonlysosomal acidic compartment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:6186-6190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward, P. P., H. Chu, X. Zhou, and O. M. Conneely. 1997. Expression and characterization of recombinant murine lactoferrin. Gene 204:171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward, P. P., M. Mendoza-Meneses, B. Mulac-Jericevic, G. A. Cunningham, O. Saucedo-Cardenas, C. T. Teng, and O. M. Conneely. 1999. Restricted spatiotemporal expression of lactoferrin during murine embryonic development. Endocrinology 140:1852-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward, P. P., S. Uribe-Luna, and O. M. Conneely. 2002. Lactoferrin and host defense. Biochem. Cell Biol. 80:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinberg, E. D. 2001. Human lactoferrin: a novel therapeutic with broad spectrum potential. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 53:1303-1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wessling-Resnick, M. 2000. Iron transport. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 20:129-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wice, B. M., and J. I. Gordon. 1998. Forced expression of Id-1 in the adult mouse small intestinal epithelium is associated with development of adenomas. J. Biol. Chem. 273:25310-25319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou, X. Y., S. Tomatsu, R. E. Fleming, S. Parkkila, A. Waheed, J. Jiang, Y. Fei, E. M. Brunt, D. A. Ruddy, C. E. Prass, R. C. Schatzman, R. O'Neill, R. S. Britton, B. R. Bacon, and W. S. Sly. 1998. HFE gene knockout produces mouse model of hereditary hemochromatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2492-2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]