Abstract

Mice deficient in hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 α (HNF-1α) develop dwarfism, liver dysfunction, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Liver dysfunction in HNF-1α-null mice includes severe hepatic glycogen accumulation and dyslipidemia. The liver dysfunction may appear as soon as 2 weeks after birth. Since the HNF-1α-null mice become diabetic 2 weeks after birth, the early onset of the liver dysfunction is unlikely to be due to the diabetic status of the mice. More likely, it is due directly to the deficiency of HNF-1α in liver. Although the HNF-1α-null mice have an average life span of 1 year, the severe liver phenotype has thwarted attempts to study the pathogenesis of maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 (MODY3) and to examine therapeutic strategies for diabetes prevention and treatment in these mice. To circumvent this problem, we have generated a new Hnf-1α mutant mouse line, Hnf-1αkin/kin, using gene targeting to inactivate the Hnf-1α gene and at the same time, to incorporate the Cre-loxP DNA recombination system into the locus for later revival of the Hnf-1α gene in tissues by tissue-specifically expressed Cre recombinase. The Hnf-1αkin/kin mice in which the expression of HNF-1α was inactivated in germ line cells were indistinguishable from the HNF-1α-null mice with regard to both the diabetes and liver phenotypes. Intriguingly, when the inactivated Hnf-1α gene was revived in liver (hepatic Hnf-1α revived) by the Cre recombinase driven by an albumin promoter, the Hnf-1αkin/kin mice, although severely diabetic, grew normally and did not develop any of the liver dysfunctions. In addition, we showed that the expression of numerous genes in pancreas, including a marker gene for pancreas injury, was affected by liver dysfunction but not by the deficiency of HNF-1α in pancreas. Thus, our hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice may serve as a useful mouse model to study the human MODY3 disorder.

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 α (HNF-1α) is a liver-enriched homeodomain-containing transcription regulator that is crucial for both postnatal development and diverse metabolisms in tissues (1, 3, 5, 7, 15, 20, 24). In humans, haploinsufficiency of HNF-1α causes maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 (MODY3) (28), a non-insulin-dependent form of diabetes mellitus. In mice, however, onset of diabetes requires the inactivation of both alleles of Hnf-1α (15).

Although HNF-1α deficiency elicits diabetes in mice 2 weeks after birth, the HNF-1α-null mice are not useful for research of the pathogenesis of MODY3 or for developing therapeutic strategies for diabetes prevention and treatment, because HNF-1α deficiency also results in the early onset of severe liver dysfunction and growth retardation (15, 18). The HNF-1α-associated liver dysfunction includes dyslipidemia (hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia) and massive hepatic glycogen accumulation (15; unpublished observation). Dyslipidemia and/or glycogen accumulation occur in certain types of diabetic animals (13, 14, 19); dyslipidemia is frequently associated with type 2 diabetes in which hyperinsulinemia is commonly found, while severe glycogen accumulation can be found in poorly controlled type 1 diabetic patients. where hyperglycemia and insulin administration may both play a role. By contrast, the HNF-1α-null mice have a low level of circulating insulin (15), so the early onset of the liver dysfunctions in HNF-1α-null mice is unlikely to have resulted from their diabetic status, and therefore, maybe not MODY3-related.

Here, we have used a gene-targeting technology in conjunction with the Cre-loxP DNA recombination system to modify the Hnf-1α gene locus, so that the Hnf-1α locus is programmed silent, not knocked out, in mouse germ line cells and can be reactivated later in a tissue-specific manner. We reactivated the liver Hnf-1α in the new mutant mice, Hnf-1αkin/−, by expressing the Cre recombinase specifically in liver. Our results demonstrate that the Hnf-1α gene, although inactivated in germ line cells, could later function properly if reactivated. We also demonstrated that in HNF-1α-null mice the liver dysfunction is due directly to the hepatic deficiency of HNF-1α, which may in turn have caused pancreatic injury and affected expression of numerous genes important in pancreas functions. Most importantly, we have established a mouse MODY model that can be used to investigate further for MODY3 pathogenesis and therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Hnf-1αkin/kin, Hnf-1αkin/−, and Hnf-1αkin/−/alb.cre mice

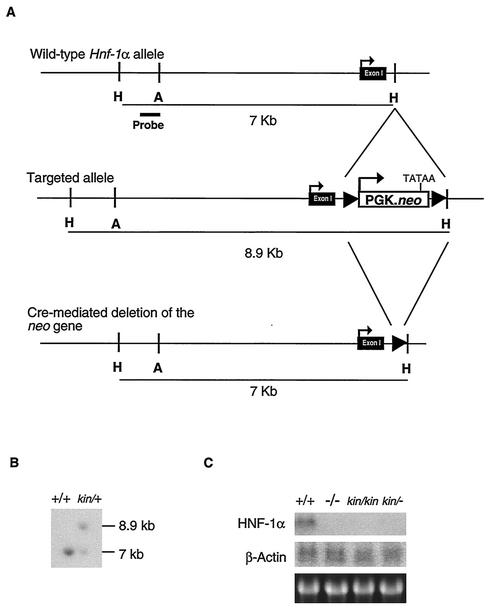

The Hnf-1α genomic fragment used for the preparation of the gene-targeting construct has been described previously (15). In this targeting construct, the loxP-PGK.neo-loxP expression cassette was inserted into a HindIII site downstream of exon I (Fig. 1A). ES cells (RW4; Genome Systems) were electroporated with the linearized targeting vector DNA, and G418-resistant clones were selected, expanded, and analyzed by Southern blotting with a 5′ probe to identify specific homologous recombinants. The correctly targeted ES cells were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts to generate chimeric founder mice as described previously (12). Chimeric male founders with an approximate agouti coat color of 90 to 100% were bred with C57BL/6J females. Offspring showing germ line transmission of the mutant allele (designated as the kin allele) were interbred and crossed to Hnf-1α+/− mice (15) to generate homozygous Hnf-1αkin/kin and Hnf-1αkin/− mice, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Targeted modification of the Hnf-1α gene locus. (A) Hnf-1α gene (top), targeted allele (middle), and the expected Cre-loxP-mediated deletion of the PGK.neo transgene (bottom). (B) Southern blot analysis of the representative ES clone that was correctly targeted. ES DNA was digested with HindIII and probed with the probe shown in panel A. (C) Northern blot analysis of representative liver biopsy specimens of Hnf-1αkin/kin mice. Liver total RNAs (10 μg) from 6-week-old Hnf-1αkin/kin mice were denatured and electrophoresed on a formaldehyde-containing 1% agarose gel, blotted to a nylon membrane, and probed with the indicated cDNA probe. Symbols and abbreviations: +, wild-type allele; −, HNF-1α-null allele; kin, PGK.neo knockin HNF-1α allele.

Heterozygous Hnf-1αkin/+ mice were then bred with alb.cre transgenic mice (22). Heterozygous Hnf-1αkin/+ mice carrying the alb.cre transgene were selected and further bred with Hnf-1α+/− mice to generate Hnf-1αkin/− mice carrying the alb.cre transgene.

PCR identification of the modified Hnf-1α alleles.

Fig. 2A shows the primer sets designed to identify different locus modifications. The sequences for the primers are as follows: for H-1, 5′-TGGCCGCTGGGGCCAGGGT; for H-2, 5′-CTAGACGGGAAGTGAAGCTTGC; for H-3, 5′-CACGGATGACGATGGGGAAGACTTC; and for Lp, 5′-TCAGACCTAATAACTTCGTATAGCA.

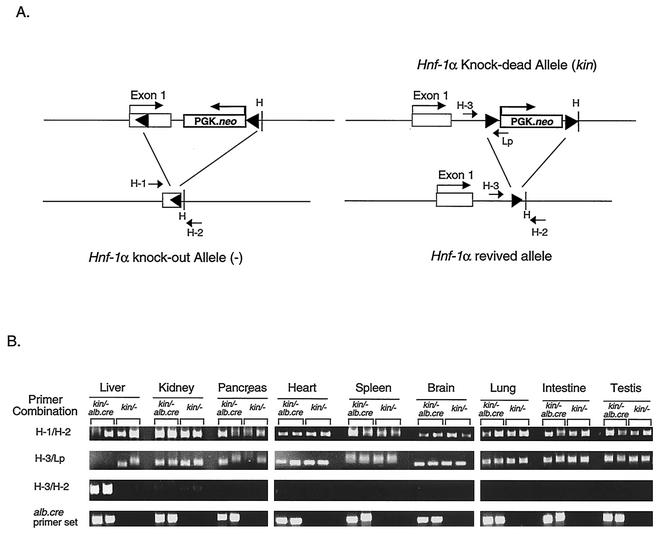

FIG. 2.

PCR analysis of the Hnf-1α gene structure. (A) Structure of the Hnf-1α alleles after Cre-mediated DNA recombination and the PCR genotyping strategy. The PCR primer design for genotyping the targeted and recombined Hnf-1α alleles is shown. (B) Results of PCR analysis of the Hnf-1α alleles in tissues of 6-week-old Hnf-1αkin/kin mice. The PCR products were analyzed in ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel. Symbols and abbreviations: +, wild-type allele; −, HNF-1α-null allele; kin, PGK.neo knockin HNF-1α allele.

The conditions of PCR amplification for each primer set were 35 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 58°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 20 s.

Southern blot analysis.

Isolated embryonic stem (ES) cell DNA or mouse tail DNA was digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme, electrophoresed in a 0.5% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane (GeneScreen Plus; Dupont) and hybridized with probes derived from the Hnf-1α gene as indicated in Fig. 1A.

Histological analysis of liver tissues.

Liver biopsy specimens were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered saline-buffered paraformaldehyde solution for embedding in paraffin. Sections of 5 μm were cut and mounted on polylysine-coated slides. The paraffin tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin solutions.

Analyses of serum chemistries and levels of IGF-I and insulin.

Mouse serum taken from various developmental stages was analyzed in an auto-dry chemical analyzer (SP4410; Spotchem) to monitor levels of serum glucose, cholesterol, and other blood chemistries. Serum insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and insulin were assayed with the respective enzyme immunoassay kit (DRG-Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany).

RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis.

Frozen mouse tissues were homogenized in TRIzol RNA reagent (GIBCO-BRL), and total RNAs were isolated according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA (10 μg) was denatured, electrophoresed, transferred to a nylon membrane, and probed with cDNA probes by a standard protocol.

RT-PCR analysis.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed using the Ready-To-Go RT-PCR beads (Amersham Pharmacia). Two micrograms of total RNA isolated from frozen pancreas sample were used for each of RT-PCR analyses of the indicated genes. RT-PCR products were than electrophoresed in 2% agarose gel, transferred to nylon membrane, and probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide derived from the desired PCR region of each gene.

The primer sets used to amplify pancreatic transcripts are as follows: HNF-4 forward primer, 5′-CTCGGAGGGTCTGCCAGTGATGC; HNF-4 backward primer, 5′-GAAGACGATGACTTCAACTTGAG; NeuroD1 forward primer, 5′-GCCTACAGCGCAGCTCTGGAGC; NeuroD2 backward primer, 5′-GTCACTGTACGCACAGTGGATTC; Pdx-1 forward primer, 5′-GCAGTGATGTTGAACTTGACCG; Pdx-1 backward primer, 5′-CCAGAAGCTCGCAGCATCTCTCCG.

The oligonucleotides used to identify PCR products are as follow: HNF-4, 5′-GCTCCTGCCAGGAGCCATCAC; NeuroD1, 5′-CGCTCAGCATCAATGGCAAC; Pdx-1, 5′-CAAGATTGTGCGGTGACCTCG.

Glycogen determination.

Livers were weighed and homogenized in 4% perchloric acid-0.5 mM EDTA. Anthrone reagent was used to determine glycogen content of the liver samples (4). Student's t test was performed to calculate the P values for significance in comparison of sample group.

RESULTS

Disruption of HNF-1α expression in Hnf-1αkin/kin mice.

The loxP-flanking PGK.neo cassette knockin vector was constructed to inactivate the Hnf-1α gene locus (Fig. 1A). The PGK.neo cassette was inserted into the first intron to serve as the targeting selection marker. The transcriptional direction of the PGK.neo inserted into the Hnf-1α locus was the same as that of the Hnf-1α gene. After germ line transmission of the PGK.neo knockin allele (kin in Fig. 1B), mice heterozygous for the kin allele were interbred or crossed with the mice heterozygous for the Hnf-1α knockout allele (15) to generate Hnf-1αkin/kin homozygotes or Hnf-1αkin/− mice, respectively. The insertion of the PGK.neo marker gene into the first intron of the Hnf-1α gene locus effectively abolished the expression of the HNF-1α transcript in both the Hnf-1αkin/kin homozygotes and the Hnf-1αkin/− mice (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, both Hnf-1αkin/kin and Hnf-1αkin/− mice exhibited phenotypes similar to those of HNF-1α-null mice (15) in their appearance (size, body proportion, and viability, etc.; data not shown) and growth rate (see below); neither Hnf-1αkin/kin nor Hnf-1αkin/− were fertile for both sexes.

Reactivation of hepatic HNF-1α expression from the Hnf-1αkin allele.

To remove the PGK.neo marker gene from the Hnf-1α locus specifically in liver, a cre transgenic mouse line, alb.cre (22), in which the expression of Cre recombinase is driven by the albumin promoter, was used to breed with Hnf-1αkin/+ or Hnf-1α+/− heterozygous mice. Mice carrying the alb.cre transgene and heterozygous for the kin or − allele were selected for further breeding with the Hnf-1α+/− or Hnf-1αkin/+ mice, respectively, to generate Hnf-1αkin/−/alb.cre (hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived) mice.

Figure 2A shows the PCR approach used to identify the targeted Hnf-1α alleles before and after the Cre-mediated DNA recombination. The H-3-Lp primer combination was used to detect the presence of the PGK.neo marker gene, while the use of the H-3-H-2 combination was to amplify a DNA fragment only present once the PGK.neo marker gene has been deleted from the Hnf-1α gene locus. Subsequently, the genomic DNA from various tissues of the hepatic Hnf-1α-revived mice were isolated and compared to those of Hnf-1αkin/− mice. As expected, the Cre recombinase expressed specifically in liver had deleted the PGK.neo marker gene from the Hnf-1α gene locus efficiently and specifically in liver (Fig. 2B). In the liver of hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice, the deletion of the PGK.neo was detected only in liver but not in other tissues, as shown by the presence of PCR product from the H-3-H-2 primer combination. On the other hand, except for liver, the presence of the PGK.neo could be detected in all other tissues examined as shown by the presence of PCR product from the H-3-Lp primer combination (Fig. 2B).

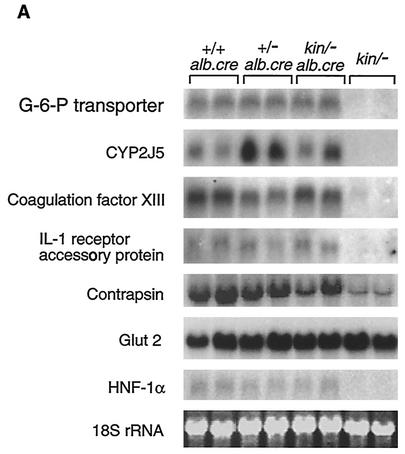

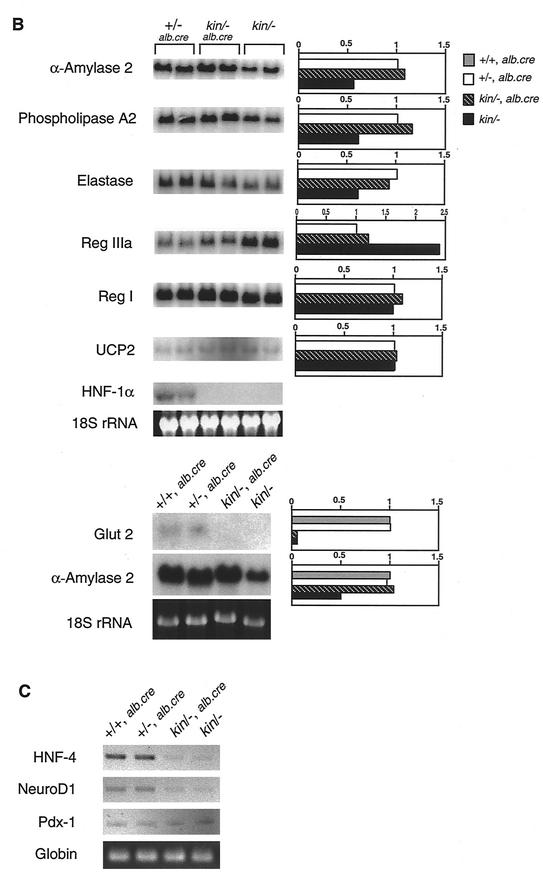

Most importantly, the Cre-mediated deletion of the PGK.neo marker gene from the Hnf-1α gene locus restored hepatic HNF-1α transcription as shown in Fig. 3A. Consequently, in hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice, the mRNA levels of those factors whose expression in liver are regulated by HNF-1α and were abolished or significantly reduced in the liver of Hnf-1αkin/− mice were restored to levels similar to those in control mice (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of gene expression profiles between 6-week-old HNF-1α-null (Hnf-1αkin/−) and hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived (Hnf-1αkin/−/alb.cre) mice. Northern blot analysis of representative liver (A) and pancreas (B) samples and RT-PCR analysis of pancreas samples (C). For Northern blot analysis, total RNAs (10 μg) of the 6-week-old mice were denatured and electrophoresed on a formaldehyde-containing 1% agarose gel, blotted to a nylon membrane, and probed with the indicated cDNA probe. Each lane contains RNA from an individual animal. Quantitative measurements were obtained by densitometry, and the ratio of expression (shown as bars to the right of the Northern blots) was obtained by comparing the mean value of the samples examined to that of the +/-, alb.cre mice. For RT-PCR analysis, 2 μg of pancreas total RNAs from the 6-week-old mice were used. RT-PCR products were probed with 32P-labeled, gene-specific oligonucleotide. The RT-PCT product of globin (bottom panel) was shown only in ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel. Symbols and abbreviations: +, wild-type allele; −, HNF-1α-null allele; kin, PGK.neo knockin HNF-1α allele.

Normal growth and liver functions in the liver Hnf-1α-revived mice.

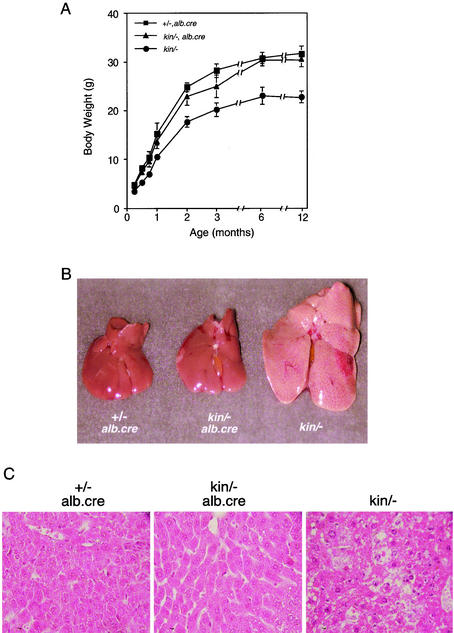

Unlike the previously reported HNF-1α-null mice, Hnf-1α−/− mice (15), or Hnf-1αkin/− mice described here, both sexes of the hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice (Hnf-1αkin/−/alb.cre) were viable, fertile, and undistinguishable in appearance from control mice. The hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice did not differ from their heterozygous littermates, Hnf-1αkin/+ or Hnf-1α+/−, in their growth rate as measured by body weight gain (Fig. 4A). By contrast, the Hnf-1αkin/− mice (without the alb.cre transgene) were retarded in growth and showed the dwarfism similar to that previously reported for HNF-1α-null mice (15). Indeed, the levels of circulating IGF-I, produced mainly in liver and mediating many growth factor functions, were restored in the hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice (Table 1). In addition, blood chemistry analyses showed that the levels of cholesterol and triacylglyceride in the hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice were significantly lower than those in Hnf-1αkin/− mice and did not differ from those in control mice (Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Normal growth and liver histology of the hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived (Hnf-1αkin/−/alb.cre) mice. (A) Growth curve for female Hnf-1αkin/−/alb.cre mice on a standard diet. Appearance (B) and histological sections and hematoxylin and eosin staining (C) of liver samples from 5-week-old Hnf-1αkin/−/alb.cre mice. (A) Values presented are the means ± standard errors (error bars) for data from four female mice. Symbols and abbreviations: +, wild-type allele; −, HNF-1α-null allele; kin, PGK.neo knockin HNF-1α allele.

TABLE 1.

Serum chemistry of Hnf-1α gene-targeted micea

| Serum component | Mean concn ± SD in mouse group

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| +/− alb.Cre+/− (n = 4) | kin/− alb.Cre+/− (n = 5) | kin/− (n = 4) | |

| Growth factors | |||

| Insulin (pmol/liter) | 112 ± 17 | 40 ± 11b | 29 ± 5b |

| IGF-I (ng/ml) | 525 ± 63 | 498 ± 55 | 203 ± 34b |

| Other components | |||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 123 ± 24 | 311 ± 73 | 290 ± 56 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 93 ± 4 | 100 ± 6 | 288 ± 28 |

| Triacylglyceride (mg/dl) | 42 ± 14 | 67 ± 41 | 135 ± 8 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 |

| Glucose oxidase (IU/liter) | 95 ± 11 | 108 ± 33 | 135 ± 108 |

| Glutamic pyruvic trans- aminase (IU/liter) | 23 ± 1 | 21 ± 14 | 135 ± 109 |

Sera were collected from mice of each genotype at 6 weeks old and subjected to analysis for serum components (n, number of mice analyzed for each genotype).

P < 0.01 (the P value [Student's t test] indicates the level of significance for differences compared to the control mice [Hnf-1α+/−, alb.Cre+/−]).

Furthermore, histology of livers from the hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice did not reveal any of the abnormalities, such as the hepatomegaly, fatty liver and vacuous hepatocytes, that were associated with the livers of both the HNF-1α null mice, Hnf-1α−/− and Hnf-1αkin/− (Fig. 4B and 3C).

Diabetic status of the hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice.

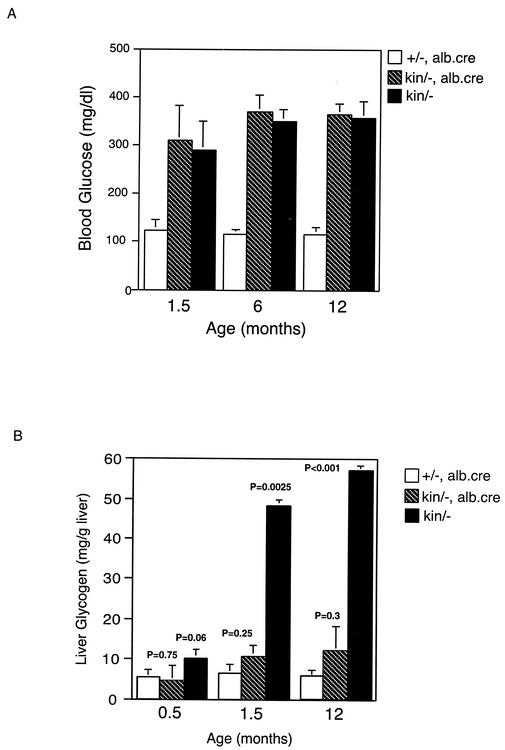

HNF-1α plays an important role in regulating pancreatic insulin production to maintain a normal glucose level in blood (15). In hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice, the Hnf-1α gene locus was reactivated only in the liver, and therefore, the expression of HNF-1α remained undetectable in the pancreas (Fig. 3B). As in Hnf-1αkin/− mice, both sexes of the hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice developed hyperglycemia 2 weeks after birth, and their blood insulin levels were significantly lower than those in control mice (Table 1). In addition, despite lacking the liver phenotypes that are associated with Hnf-1α−/− and Hnf-1αkin/− mice, the severity of hyperglycemia in the hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice was similar to that displayed in Hnf-1αkin/− mice at any age examined (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Persistent hyperglycemia but normal hepatic glycogen content in the liver Hnf-1α-revived mice. Serum glucose (A) and liver glycogen (B) levels of the Hnf-1αkin/kin/alb.cre mice at the different ages. Values presented are the means ± standard errors (error bars) for data from three to four serum or liver samples. The P value indicates the level of significance for differences compared to the control mice (+/−, alb.cre).

In diabetic HNF-1α-null mice, glycogen markedly accumulated in the liver, and hepatomegaly developed before puberty (Fig. 4B and 5B) (15). Hepatic glycogen accumulation may occur in some diabetic animal models and may be caused, in part, by the hyperglycemic status (14, 27). Interestingly, the liver glycogen levels in hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice, which were severely diabetic, were greatly reduced to a degree that was not significantly different from that in normal mice at the age examined (Fig. 5B), indicating that the hepatic glycogen accumulation in HNF-1α-null mice was unrelated to their diabetic state.

Effects of hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived on pancreatic gene expression.

In HNF-1α-null (Hnf-1αkin/−) mice, the expression of numerous pancreatic genes was affected in comparison to those in normal mice (Fig. 3B and C). To examine whether there were any differences in pancreatic gene expression between hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice and HNF-1α-null mice in which both diabetes and liver phenotypes had developed, the expression of various pancreatic genes was examined. As shown in Fig. 3B and C, the expression of genes, such as Glut2, HNF-4, and NeuroD1, that are down regulated in the HNF-1α-null mice and have been attributed to their pancreatic defect (21, 25) remained undetectable or down regulated in pancreas of hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice. However, the expression levels of the genes encoding secreted protein α-amylase 2, phospholipase A2, and elastase, although reduced in the pancreas of HNF-1α-null mice, were normal in that of hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice. Similarly, the elevated expression of pancreatic regenerating factor, Reg IIIa, in HNF-1α-null mice was not present in hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice (Fig. 3B).

DISCUSSION

We have generated a new HNF-1α mutant mouse line, Hnf-1αkin, by a gene targeting approach to incorporate a loxP flanking marker gene into the first intron of the Hnf-1α gene locus. By using this strategy, the Hnf-1α allele was inactivated but not knocked out, so that the knocked-dead Hnf-1α allele was revived later in tissue at the chosen developmental stage, once Cre recombinase was introduced to delete the marker gene from the locus. By using a cre transgenic mouse line, alb.cre, in which the expression of the cre gene is driven by the albumin promoter active only in liver (22), the inactivated Hnf-1α gene locus was reactivated only in liver, and the expression of genes that are regulated by HNF-1α was restored.

Most importantly, before introducing the Cre recombinase, the homozygous inactivated mice, Hnf-1αkin/kin, were indistinguishable from HNF-1α-null mice reported earlier (15) in their diabetes and liver phenotypes. Upon introducing the alb.cre transgene, the Hnf-1αkin/kin mice remained diabetic but no longer showed the liver dysfunction, such as massive glycogen accumulation and fatty liver. This indicates not only that the liver dysfunction in the diabetic HNF-1α-null mice results directly from the deficiency of HNF-1α in liver but also that the Hnf-1α gene, although inactivated in germ line cells, can later function properly in tissues when revived by Cre recombinase.

In HNF-1α-null mice, glycogen markedly accumulated in the liver, and hepatomegaly developed before puberty. Although glycogen accumulation in liver occurs in certain types of diabetic animals (14, 27), marked hepatomegaly caused by cytoplasmic glycogen deposition is mainly found in poorly controlled type 1 diabetic patients, in whom hyperglycemia and insulin administration may both play a role in causing the hepatocellular glycogen deposition by their actions on glycogen phosphorylase and synthase, thereby stimulating the accumulation of glycogen (14). Thus, hyperglycemia alone is unlikely to be the reason that promotes the severe glycogen accumulation in the liver of HNF-1α-null mice. More likely, glycogen accumulation in liver of the regular HNF-1α-null mice was due directly to the deficiency in HNF-1α and its downstream regulated genes involving in glycogen metabolism, such as glucose-6-phosphate transporter (11). Accordingly, the degree of hepatic glycogen accumulation should be significantly reduced in the diabetic hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice in which the expression of HNF-1α and glucose-6-phosphate transporter was restored in liver. Indeed, glycogen accumulation was not found in the liver of hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice, indicating that the severe hepatic glycogen accumulation in HNF-1α-null mice was unrelated to their diabetic state and was caused directly by the HNF-1α deficiency in liver.

MODY is a disorder characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance, nonketotic diabetes mellitus, an age of onset usually before 25 years and often in childhood or adolescence, and a major defect in pancreatic β-cell function (8). In humans, there are at least six different genes which if defective in the heterozygous state can lead to pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and result in MODY (2, 8). These genes encode the glycolytic enzyme glucokinase (MODY2) and five transcription factors: HNF-4 α (MODY1), HNF-1α (MODY3), insulin promoter factor 1 (MODY4), HNF-1β (MODY5), and NeuroD1 (MODY6). In addition to their critical role in pancreatic function, these MODY genes are expressed and play important roles in other tissues as demonstrated recently by gene knockout experiments in mice (7, 9, 15, 16, 22, 23). Unlike humans, in whom mutations in the heterozygous state for any of the MODY genes would elicit MODY (2), mice require inactivation of both alleles of a MODY gene (except for glucokinase and insulin promoter factor 1) to induce pancreatic dysfunction and diabetes mellitus. However, except for HNF-1α and NeuroD1, complete deficiency of any other MODY factors causes embryonic lethality or early postnatal death (6, 7, 9, 15, 16, 22). Although the HNF-1α-null and majority of NeuroD1-null mice survive to adult, they show the severe, but not diabetes-related, dysfunction in other tissues (15, 16). The dysfunction, in liver for HNF-1α-null mice and in brain for NeuroD1-null mice, thwart further attempts to use these null mice for studying the MODY pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. The hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice described here have an early onset and persistent hyperglycemia but do not develop liver illness. Hence, this new mouse line may provide a useful mouse model for studying human MODY3 disease.

In glucokinase-related diabetes (MODY2), hyperglycemia is due to impaired glucokinase function in both the liver and pancreatic β cells (23). In HNF-1α-related diabetes, however, as indicated by our results from hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice, the severity of hyperglycemia appears not to be influenced by HNF-1α function in liver at the age examined, given that the blood glucose levels were unchanged regardless of whether HNF-1α expression and liver function were restored.

Liver status, however, appears to affect the expression of numerous genes in the pancreas. Some of the affected genes, such as amylase and phospholipase A2, encode secreted proteins essential in food digestion (10, 17). Among others, Reg IIIa is a protein produced by the acinar cell of the pancreas in response to injury (26). Reg III has been described as a sensitive marker for pancreatic injury in both pancreatitis and pancreatic transplant (29). Although its function remains to be elucidated, Reg IIIa may be a free-radical scavenger that prevents apoptosis of acinar cells during pancreatitis (30). Elevation of Reg III expression in the pancreas of HNF-1α-null mice indicates that pancreatic injury might exist in HNF-1α-null mice as young as 5 weeks old. In hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice, despite that the expression of pancreatic HNF-1α was not restored, the expression of Reg IIIa was normal in the pancreas. Thus, the pancreatic injury in HNF-1α-null mice, if existed, is hepatic HNF-1α-related and not caused directly by any deficiency of HNF-1α in pancreas. How hepatic HNF-1α and/or liver function affects the pancreas and pancreatic gene expression remains, however, to be explored.

To summarize, we have created a new line of HNF-1α mutant mice, Hnf-1αkin/kin, in which the Hnf-1α gene can be inactivated and later recovered by the use of tissue-specifically controlled Cre recombinase. We have used this approach to generate hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice that have an early onset of diabetes but do not carry liver dysfunction. The hepatic-Hnf-1α-revived mice may serve as a useful mouse model to study the human MODY3 disorder.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by research grant NSC-89-2311-001-078 from the National Science of Council of Taiwan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumhueter, S., D. B. Mendel, P. B. Conley, C. J. Kuo, C. Turk, M. K. Graves, C. A. Edwards, G. Courtois, and G. R. Crabtree. 1990. HNF-1 shares three sequence motifs with the POU domain proteins and is identical to LF-B1 and APF. Genes Dev. 4:372-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell, G. I., and K. S. Polonsky. 2001. Diabetes mellitus and genetically programmed defects in β-cell function. Nature 414:788-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenfeld, M., M. Maury, T. Chouard, M. Yaniv, and H. Condamine. 1991. Hepatic nuclear factor 1 (HNF 1) shows a wider distribution than products of its known target genes in developing mouse. Development 113:589-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll, N. V., R. W. Longley, and J. H. Roe. 1955. The determination of glycogen in liver and muscle by use of anthrone reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 212:335-343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Simone, W., L. De Magistris, D. Lazzaro, J. Gerstner, P. Monaci, A. Nicosia and R. Cortese. 1991. LFB3, a heterodimer-forming homeoprotein of the LEB1 family, is expressed in specialized epithelia. EMBO J. 10:1435-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dukes, I. D., S. Sreenan, M. W. Roe, M. Levisetti, Y. P. Zhou, D. Ostrega, G. I. Bell, M. Pontoglio, M. Yaniv, L. Philipson, and K. S. Polonsky. 1998. Defective pancreatic-cell glycolytic signaling in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 273:24457-24464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan, S. A., A. Nagy and W. Chan. 1997. Murine gastrulation requires HNF-4 regulated gene expression in the visceral endoderm: tetraploid rescue of Hnf-4(-/-) embryos. Development 124:279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fajans, S. S., G. I. Bell, and K. S. Polonsky. 2001. Molecular mechanisms and clinical pathophysiology of maturity-onset diabetes of the young. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:971-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habener, J. F., and D. A. Stoffers. 1998. A newly discovered role of transcription factors involved in pancreas development and the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians 110:12-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedemann, M. S., A. R. Pedersen, and R. M. Engberg. 2001. Exocrine pancreatic secretion is stimulated in piglets fed fish oil compared with those fed coconut oil or lard. J. Nutr. 131:3222-3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiraiwa, H., C.-J. Pan, B. Lin, T. E. Akiyama, F. J. Gonzalez, and J. Y. Chou. 2001. A molecular link between the common phenotypes of type 1 glycogen storage disease and HNF1α-null mice. J. Biol. Chem. 276:7963-7967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan, B., R. Bedington, F. Costantini, and E. Lacy. 1994. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 13.Howard, B. V. 1985. Lipoprotein metabolism in diabetes mellitus. J. Lipid Res. 28:613-628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence, J. C., Jr., and P. J. Roach. 1997. New insights into the role and mechanism of glycogen synthase activation by insulin. Diabetes 46:541-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, Y. H., B. Sauer, and F. J. Gonzalez. 1998. Laron dwarfism and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in the Hnf-1α Knockout mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:3059-3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, M., S. J. Pleasure, A. E. Collins, J. L. Noebels, F. J. Naya, M. J. Tsai, and D. H. Lowenstein. 2000. Loss of BETA2/NeuroD leads to malformation of the dentate gyrus and epilepsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:865-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandal, A. K., Z. Zhang, J. Y. Chou, and A. B. Mukherjee. 2001. Pancreatic phospholipase A2 via its receptor regulates expression of key enzymes of phospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism. FASEB J. 15:1834-1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muppala, V., C.-S. Lin, and Y. H. Lee. 2000. The role of HNF-1α in controlling hepatic catalase activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 57:93-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Looney, P., D. Irwin, P. Briscoe, and G. V. Vahouny. 1985. Lipoprotein composition as a component in the lipoprotein clearance defect in experimental diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 260:428-432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pontoglio, M., J. Barra, M. Hadchouel, A. Doen, C. Dress, J. P. Bach, C. Babinet, and M. Yaniv. 1996. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 inactivation results in hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, and renal Fanconi syndrome. Cell 84:575-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pontoglio, M., B. Sreenan, M. Roe, W. Pugh, D. Ostrega, A. Doyen, A. J. Pick, A. Baldwin, G. Velho, P. Froguel, M. Levisetti, S. Bonner-Weir, G. I. Bell, M. Yaniv, and K. S. Polonsky. 1998. Defective insulin secretion in hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α-deficient mice. J. Clin. Investig. 101:2215-2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postic, C., M. Shiota, K. D. Niswender, T. L. Jetton, Y. Chen, J. M. Moates, K. D. Shelton, J. Lindner, A. D. Cherrington, and M. A. Magnuson. 1999. Dual roles for glucokinase in glucose homeostasis as determined by liver and pancreatic β cell-specific gene knock-outs using cre recombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Postic, C., M. Shiota, and M. A. Magnuson. 2001. Cell-specific roles of glucokinase in glucose homeostasis. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 56:195-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shih, D. Q., M. Bussen, E. Sehayek, M. Ananthanarayanan, B. L. Shneider, F. J. Suchy, S. Shefer, J. S. Bollileni, F. J. Gonzalez, J. L. Breslow and M. Stoffel. 2001. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1α is an essential regulator of bile acid and plasma cholesterol metabolism. Nat. Genet. 27:375-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shih, D. Q., S. Screenan, K. N. Nunoz, L. Philipson, M. Pontogolio, M. Yaniv, K. S. Polonsky, and M. Stoffel. 2001. Loss of HNF-1α function in mice leads to abnormal expression of genes involved in pancreatic islet development and metabolism. Diabetes 50:2472-2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stephanova, E., F. Tissir, N. Dusetti, J. Iovanna, and C. Szpirer. 1996. The rat genes encoding the pancreatitis-associated proteins I, II, and III (Pap1, Pap2, Pap3) and the lithostatin/pancreatic stone protein/regeneration protein (reg) colocalize at 4q33-4q34. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 72:83-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Steenbergen, W., and S. Lanckmans. 1995. Liver disturbances in obesity and diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 19(Suppl. 3):S27-S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamagata, K., N. Oda, P. J. Kaisaki, S. Menzel, H. Furuta, M. Vaxillaire, L. Southam, R. D. Cox, G. M. Lathrop, V. V. Borirai, X. Chen, N. J. Cox, Y. Oda, H. Yano, M. M. Le Beau, S. Yamad, H. Nishigori, J. Takeda, S. S. Fajans, A. T. Hattersley, N. Iwasaki, T. Hansen, O. Pedersen, K. S. Polonsky, R. C. Turner, G. Velho, J.-C. Chevre, P. Froguel, and G. I. Bell. 1996. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1α gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY3). Nature 384:455-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zenilman, M. E., T. H. Magnuson, K. Swinson, J. Egan, R. Perfetti, A. R. Shuldiner. 1996. Pancreatic thread protein in mitogenic to pancreatic-derived cells in culture. Gastroenterology 110:1208-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zenilman, M. E., D. Tuchman, W. Zheng, J. Levine, and H. Delany. 2000. Comparison of reg I and reg III levels during acute pancreatitis in the rat. Ann. Surg. 232:646-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]