Abstract

Subcellular localization of the transcription factor Prospero is dynamic. For example, the protein is cytoplasmic in neuroblasts, nuclear in sheath cells, and degraded in newly formed neurons. The carboxy terminus of Prospero, including the homeodomain and Prospero domain, plays roles in regulating these changes. The homeodomain has two distinct subdomains, which exclude proteins from the nucleus, while the intact homeo/Prospero domain masks this effect. One subdomain is an Exportin-dependent nuclear export signal requiring three conserved hydrophobic residues, which models onto helix 1. Another, including helices 2 and 3, requires proteasome activity to degrade nuclear protein. Finally, the Prospero domain is missing in prosI13 embryos, thus unmasking nuclear exclusion, resulting in constitutively cytoplasmic protein. Multiple processes direct Prospero regulation of cell fate in embryonic nervous system development.

The prospero (pros) locus was originally identified and cloned because of its expression in and effects on the developing Drosophila nervous system (9, 28, 36). Prospero contains a DNA-binding homeodomain (5, 28, 36) and was proposed to act as a transcription factor because pros mutations alter the expression of other genes normally expressed in the developing nervous system. The carboxy-terminal 236 amino acids of Prospero (amino acids 1172 to 1407), which include the homeodomain, the Prospero domain, and additional residues amino terminal to the homeodomain, was shown to bind a specific DNA sequence (14) and activate the transcription of reporter genes in transiently transfected tissue culture cells (7, 14).

Prospero is first detected in the nervous system stem cells or neuroblasts, where it is uniformly cytoplasmic. Before cell division, Prospero relocates to the basal cortex, where it is tethered by attaching to the adapter protein, Miranda (18, 32). A neuroblast divides asymmetrically to regenerate a neuroblast and produce a ganglion mother cell, partitioning all of the Prospero protein to the ganglion mother cell, where it translocates into the nucleus and functions as a transcription factor (16, 33). The ganglion mother cell, which is now committed to differentiate, divides once more to generate two postmitotic neuronal and/or glial cells. In neurons, Prospero is degraded to undetectable levels (36).

There is a direct correlation between Prospero protein and cell fates during patterning of the Drosophila nervous system. For example, Prospero is a critical regulator of the switch from proliferation of neuroblasts to differentiation of ganglion mother cells. In embryos lacking the pros locus, neuroectodermal cells undergo ectopic cell divisions. In contrast, overexpression of Prospero blocks cell division (26). Another example is the external sense organ precursor cell lineage, where the decision to be a IIa or IIb cell depends on the presence of Prospero protein in the latter (27, 31). Furthermore, when IIb cells produce neuronal and sheath daughter cells, Prospero is degraded in the neurons but not the sheath cells (27).

Regulated nuclear transport controls the activity of numerous signaling molecules and transcription factors (reviewed in reference 21). It was previously shown that 164 amino acids from the carboxy terminus of Prospero, including the short isoform of the homeodomain and adjacent Prospero domain, which we will refer to as the homeo/Prospero domain, regulate the protein's nuclear transport (7). When transfected into mammalian tissue culture cells, proteins including an intact homeo/Prospero domain are either nuclear, if they also include the GAL4 nuclear localization signal (NLS) or both the GAL4 and Prospero NLSs, or ubiquitous if they lack an NLS. Mutation of the Prospero domain results in accumulation of the proteins in the cytoplasm, even if they include the NLS sequences mentioned above. This result is similar to what is seen in prosS8 embryos, where Prospero protein missing the last 30 amino acids of the Prospero domain is cytoplasmic in ganglion mother cells (7). We conclude that transiently transfected tissue culture cells faithfully reproduce the effects observed in embryos and therefore serve as an efficient model system for further dissection of the regulation of Prospero subcellular localization. Demidenko et al. (7) went on to identify a 28-amino-acid region at the beginning of the homeodomain that functions as a nuclear export signal (NES) and to demonstrate that the highly conserved 100-amino-acid Prospero domain functions as an NES mask.

We demonstrate here that the Prospero homeodomain has two separable sequences that exclude fusion proteins from the nucleus; the first is the previously described Exportin-dependent NES, and the second is dependent on proteasome activity to degrade nuclear protein. Both depend on homeodomain sequence as mutations of specific amino acids abrogate function. We also demonstrate that the intact homeo/Prospero domain is required for masking nuclear exclusion. We conclude that there are multiple levels of regulation for Prospero protein activity and that this directs the fate of postmitotic cells in the formation of the nervous system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

Primers were designed to amplify, by using PCR (Pfu DNA polymerase; Stratagene), different regions from the short isoform of a pros cDNA clone. To generate clones of short regions of Prospero, the primers used add BamHI and XbaI restriction sites to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the amplified DNA. This DNA was restriction digested, gel purified, and cloned into the vector pEYFP-Nuc (Clontech), which expresses an enhanced yellow variant of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). These clones express at high levels in mammalian cells chimeric proteins with the amino terminus of EYFP fused to three consensus simian virus 40 (SV40) NLSs, followed by regions of Prospero. The SV40 NLS sequences were removed by restriction digestion with BglII and BamHI, dilution and religation, creating the vector pEYFP. The sequence of all clones was checked on an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer. The Prospero amino acid sequences encoded by the resulting clones are shown in Table 1. To generate a wild-type clone including the Prospero NLS, the primers used add BglII and XbaI sites and utilized the regular Prospero stop codon. This clone, Pros-NLS+, was then modified with additional primers to introduce the G-to-A transition and to delete the AG, as are found in the prosS8 and prosI13 mutant alleles. The resulting protein sequence beginning and end points are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Amino acids included in Prospero fusion proteins

| Pros region | Amino acid sequence |

|---|---|

| HDA | GMAPTSSTLTPMHLRKAKLMFFWVRYPSa |

| HDB | SAVLKMYFPDIKFNKNNTAQLVKWFSNFREFYYIQMa |

| HDC | GMAPTSSTLTPMHLRKAKLMFFa |

| HDD | WVRYPSSAVLKMYFPDIKFNa |

| HDE | KNNTAQLVKWFSNFREFYYIQMa |

| PDA | EKYARQAVTEGIKTPDDLLIAGDSELYRVLNLa |

| PDB | HYNRNNHIEVPQNFRFVVESTLREFFRAIQGGKDTEQSa |

| PDC | WKKSIYKIISRMDDPVPEYFKSPNFLEQLEa |

| NLS-+ | LVVTPKKKRHKVb.............KSPNFLEQLE |

| NLS-S8 | LVVTPKKKRHKV...............................IQGGKDTEQS |

| NLS-I13 | LVVTPKKKRHKV......FSNFRILLHTNGEICTTSCHRRHQDTRc |

The amino acids SR were added at the carboxy terminus of these pEFYP fusion proteins.

The NLS is underlined.

Missense sequence is in italics.

In vitro mutagenesis.

Mutations were induced by using oligonucleotides containing the desired mutations as primers for the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

Sequence analysis.

Embryos were collected from prosI13/TM3 ftz-lacZ pros+ and prosI13/TM6B Scr-lacZ pros+ flies, which had been crossed with each other. After 48 h, genomic DNA was isolated from the dead homozygous prosI13 embryos. Primers (sequences of primers will be provided upon request) were used to amplify genomic DNA by PCR (Pfu DNA polymerase; Stratagene). The same primers were then used in sequence reactions and analyzed as described above. Total embryonic RNA from heterozygous prosI13/TM3 ftz-lacZ pros+ embryos was reverse transcribed (Quick RT-PCR kit; Qiagen). Primers on each side of the large 13.5-kb intron near the 3′ end of the region encoding the homeodomain were used to amplify (Taq2000; Stratagene) and sequence the products.

Cell culture, transfection, staining, and visualization.

CV-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and gentamicin sulfate in CO2 incubators set to 5%. For transient-transfection experiments, cells were grown on gelatin coated (0.1 to 0.2%) circular glass coverslips in 35-mm six-well plates. Then, 100 μl of Opti-MEM 1 (Gibco-BRL) was mixed with 6 μl of FuGene 6 (Roche) and 1 μg of DNA, let stand at room temperature for 15 to 45 min, added to each well, and finally incubated for 3 to 6 h. Cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for 24 to 48 h at 37°C in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium plus serum. For drug experiments, cells were mock treated with 10 μl of 70% ethanol/ml or else treated with 10 to 50 ng of leptomycin B (Sigma)/ml in 70% ethanol, 20 μM lactacystin (Calbiochem) in H2O, and 50 μM MG-115 (Calbiochem) in dimethyl sulfoxide or 50 μg of cycloheximide (Calbiochem) in ethanol/ml for 2 to 4 h prior to fixation.

Cells were washed three times in PBS and fixed for 10 min in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. They were then washed once in PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100, washed three times in PBS, and incubated with 5 μl of a mixture of RNase A (10 mg/ml) and RNase T (500 U/ml) for 60 min. Cells were washed three times in PBS and incubated with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) in PBS for 30 min. After three washes in PBS, coverslips containing the cells were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and examined by ×40 or ×63 magnification by optical sectioning on a Bio-Rad MRC1024 confocal microscope.

Western blotting.

CV-1 cells were cotransfected as described above with pEYFP and one of the following: pEFYP-Pros-NLS+, pEFYP-Pros-NLS-S8, pEFYP-Pros-NLS-I13, pEYFP-HDB, or pEYFP-HDB-F3. After 24 h, cells were mock treated or treated with either cycloheximide or MG-115 for 2 to 4 h. Cells were resuspended with trypsin and then extensively washed in PBS. Cells were sonicated in sample buffer (50 mM dithiothreitol, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 40 mM Tris-HCl; pH 6.8), heated to 70°C for 5 min, and stored at −20°C. Proteins were resolved in a sodium dodecyl sulfate-4 to 15% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with a 1:10,000 dilution of a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (Clontech) or a 1:40 dilution of MR1A anti-Prospero antibody. Antibodies were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia). Bands were quantified on a Kodak Digital Science Image Station 440.

Embryo staining.

Overnight embryo collections, from prosI13/TM3 ftz-lacZ pros+ flies, were aged 3 h, dechorionated for 3 min in 50% bleach, and fixed for 25 min with 4% formaldehyde in PEM (100 mM PIPES, pH 6.9; 1 mM MgCl2; 1 mM EGTA). Blocking and antibody detection were done as described elsewhere (17). The antibodies used were MR1A (33), a Prospero antibody used at a dilution of 1:4, and the Cappell β-galactosidase antibody (ICN) used at a dilution of 1:1,000. Nucleic acid was stained with Sytox green (Molecular Probes) at a final concentration of 1.25 μM, after treatment of embryos with RNase, as done in cells.

Protein sequence analysis and molecular modeling.

Homology-based molecular modeling of the Prospero homeodomain was performed as follows. First, a multiple sequence alignment of several available Prospero homeodomain sequences was constructed by using CLUSTALW (15). Second, this alignment was used to construct a generalized sequence profile and searches were run against the database of protein sequences with the known structures (PDB) by using the PFTOOLS package (3). Third, the alignments with the highest-scoring sequences were selected. Finally, manual alignment corrections were applied whenever necessary based on the known homeodomain structures. The resulting alignments were used for molecular modeling of the Prospero homeodomain. The structural models were built by using the HOMOLOGY module of Insight II program (6). The resulting structures were subjected to the 300 steps of minimization based on the steepest descent algorithm with the backbone atoms restrained to their starting positions with a force constant K of 100. The next 500 steps of the refinement were performed without any restrictions by using the conjugate gradients algorithm. The CHARMM force field (2) and the distance-dependent dielectric constant were used for the energy calculations. The program PROCHECK (25) was used to check the quality of the modeled structure. Images (see Fig. 3B to D) were generated by using Insight II (6).

FIG. 3.

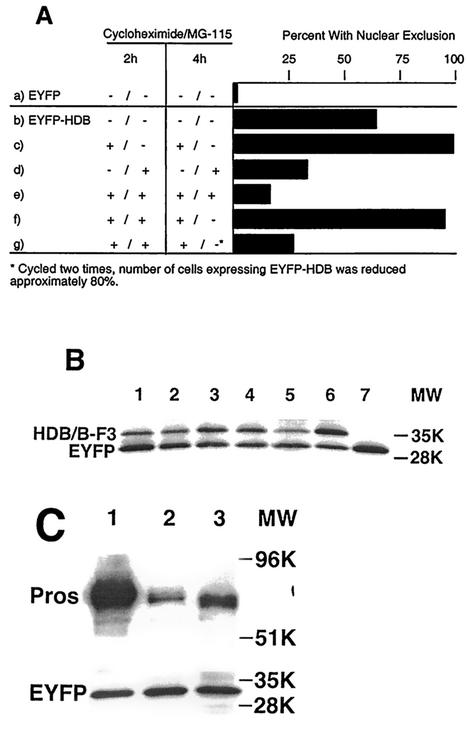

The HDB subdomain targets nuclear proteins for degradation. (A) CV-1 cells were transfected, left untreated, or treated with inhibitors of protein synthesis (cycloheximide) and/or proteasome activity (MG-115). The percentages of expressing cells with reduced fusion protein levels in the nucleus are shown. (a) None of the pEYFP transfected cells showed nuclear exclusion. (b) Untreated cells transfected with pEYPF-HDB were compared with those treated with cycloheximide (c and e to g) and/or MG-115 (d to g) for the indicated times. (c) Cycloheximide increases the percentage of expressing cells showing nuclear exclusion. (d) MG-115 decreases the percentage of expressing cells showing nuclear exclusion. (e) Treatment with both cycloheximide and MG-115 further decreases the percentage. (f) Nuclear exclusion is restored by removing MG-115 for 2 h. (g) The treatments in panel e were repeated for an additional cycle, greatly reducing the percentage of expressing cells showing nuclear exclusion, in large part because fewer cells express the fusion protein. (B) Fusing either HDB or HDB-F3 to EYFP reduces the protein's stability. CV-1 cells were cotransfected with pEYFP alone (lane 7), with pEYFP and pEYFP-HDB (lanes 1 to 3), or with pEYFP and pEYFP-HDB-F3 (lanes 4 to 6) at a molar ratio of 1:3. Cells were mock treated (lanes 1 and 4), treated with cycloheximide (lanes 2 and 5),or treated with MG-115 (lanes 3 and 6). Proteins were resolved on a 4 to 15% polyacrylamide gel and probed with anti-GFP antibody. EYFP, EYFP-HDB, and EYFP-HDB-F3 resolve slightly higher than their predicted molecular weights of 27,500, 32,000, and 32,000. (C) Introduction of the lesions responsible for prosS8 and prosI13 reduces the size and stability of fusion proteins. CV-1 cells were cotransfected with equal molar ratios of pEYFP and either pEYFP-Pros-NLS+ (lane 1), pEYFP-NLS-S8 (lane 2), or pEYFP-NLS-I13 (lane 3). After a 4-h cycloheximide treatment, proteins were isolated and resolved as in panel B, probed with anti-GFP antibody (EYFP), and reprobed with anti-Prospero antibody (Pros).

RESULTS

The Prospero homeodomain contains two separable regions that cause the accumulation of fusion proteins in the cytoplasm.

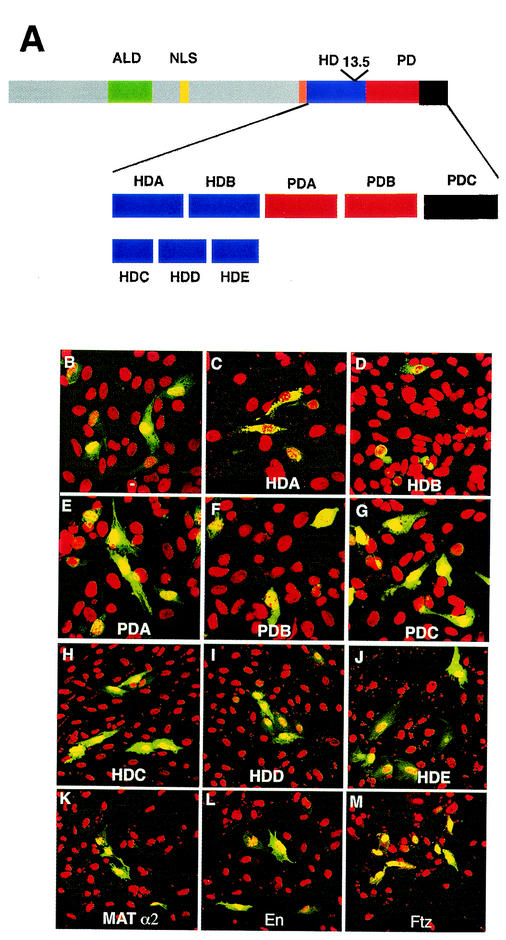

The functional domains of Prospero are shown schematically in Fig. 1A. The protein consists of an asymmetric localization domain (16), an NLS (16, 28), an alternatively spliced homeodomain (5), and the Prospero domain (4). We previously showed that the homeo/Prospero domain includes a functional NES and an NES mask. To identify any additional subdomains in the carboxy terminus of Prospero responsible for regulating the protein's subcellular localization, we created a series of EYFP-Prospero fusion proteins and examined their localization when ectopically expressed in the mammalian cell line CV-1. The amino acids constituting these subdomains are shown in Table 1. The homeo/Prospero domain was divided into five regions (Fig. 1A), and each was fused to the carboxy terminus of pEYFP. The vector pEYFP expresses GFP that is ubiquitously localized in the cell, although it is slightly enriched in the nucleus (Fig. 1B). Two fragments, HDA and HDB, result in the cytoplasmic localization of the EYFP fusion proteins (Fig. 1C and D). None of the three Prospero domain fragments results in changes of subcellular localization (Fig. 1E to G). To test whether we might have disrupted an NES (or NLS) during our division of the Prospero domain, we also examined fusion proteins with combinations of these fragments, including PDA-PDB, PDB-PDC, and the intact Prospero domain; none of these constructs change the localization of the EYFP fusion protein (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Two separate subdomains of the Prospero homeodomain result in cytoplasmic enrichment of proteins. (A) Schematic diagram of the functional domains previously identified in Prospero relative to eight fragments, HDA-HDE and PDA-PDC, of the homeo/Prospero domain that were tested for their ability to redirect subcellular localization of proteins. ALD, asymmetric localization domain (green); NLS (yellow); HD, homeodomain (orange and blue); PD, Prospero domain (red and black). The long isoform of the HD includes the domain drawn in orange and blue. The region of the PD deleted by prosS8 is shown in black. The position of the third intron (13.5 kb) is indicated. (B to J) CV-1 cells were transfected with the pEYFP vector alone (B) or fused to each of the eight indicated Prospero fragments. Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (red), and EYFP fusion proteins (green) were visualized by confocal microscopy. Both HDA and HDB preferentially accumulate fusion proteins in the cytoplasm. (K to M) The equivalent “HDA” domains from other homeodomains do not enrich fusion proteins in the cytoplasm. pEYFP fused to regions from yeast Mat α2, and Drosophila Engrailed (En) have no effect on subcellular localization, while Fushi tarazu (Ftz) enriches fusion proteins in the nucleus.

In order to refine the limits of the regions responsible for restricting the EYFP-fusion proteins to the cytoplasm, we further subdivided the homeodomain into three fragments: HDC, HDD, and HDE (Fig. 1A and Table 1). These were selected to separate each of the three helices of the homeodomain (see below). The EYFP-HDC construct has six amino acids removed from the carboxy terminus of HDA. This abrogates nuclear export function (Fig. 1H). Neither EYFP-HDD, which includes part of HDA and HDB, nor EYFP-HDE, which removes 13 amino acids from HDB's amino terminus, alter protein localization (Fig. 1I and J).

Tertiary structural constraints of all homeodomains may require the fortuitous presence of an Exportin-dependent NES. To test this possibility, we constructed EYFP fusion proteins with the amino terminus of the homeodomain proteins Mat α2, Engrailed (En), and fushi tarazu (Ftz). Neither Mat α2 nor En changes the subcellular localization of EYFP fusion proteins (Fig. 1K and L). Ftz fusion proteins accumulate in the nucleus (Fig. 1M), demonstrating the presence of a sequence that can act as an NLS.

HDA and HDB relocate fusion proteins by different mechanisms.

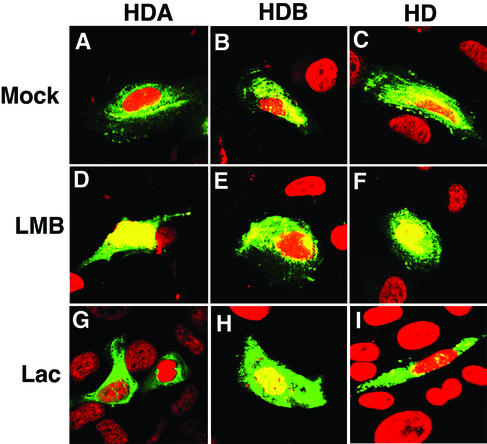

We previously demonstrated that HDA mediated nuclear export by the Exportin pathway (7), since it is inhibited by the drug leptomycin B (22-24). Here we transfected CV-1 cells with EYFP-HDA, -HDB, or -HD fusion constructs. When mock treated with 70% ethanol, all three fusion proteins preferentially accumulated in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A to C), as they do in untreated cells. Treatment with leptomycin B prevented exclusion of the HDA and HD fusion proteins from the nucleus but had no effect on the HDB fusion protein (Fig. 2D to F). This demonstrates that HDB is not an Exportin-dependent NES.

FIG. 2.

Nuclear exclusion by HDA and HDB utilizes different mechanisms. (A to I) pEYFP was fused to HDA (A, D, and G), HDB (B, E, and H), or HD (C, F, and I); transfected into CV-1 cells; mock treated (A to C), treated with leptomycin B (LMB) (D to F), or treated with lactacystin (Lac) (G to I); and then analyzed as in Fig. 1.

Neuronal differentiation is accompanied by the degradation of Prospero protein. We hypothesized that proteasome activity might be involved in the degradation of Prospero. The drug lactacystin inhibits the catalytic activity of the 20S component of the proteasome (8) and results in the differentiation of a neuroblastoma cell line (10). Treatment of transfected CV-1 cells with lactacystin prevented most exclusion of the HDB fusion protein from the nucleus but had no effect on HDA or HD (Fig. 2G to I). The proteasome inhibitor MG-115 also prevented most exclusion of HDB fusion proteins from the nucleus (data not shown).

HDB signals the degradation of nuclear fusion proteins.

To more fully characterize the apparent targeting of nuclear HDB fusion proteins for proteasome-dependent degradation, we performed a series of transfection experiments followed by drug treatment to inhibit protein synthesis with cycloheximide and/or proteasome activity with the reversible inhibitor MG-115. The resulting cells were scored for the subcellular localization of EYFP-HDB with the data presented as a percentage of the expressing cells with reduced protein levels in the nucleus compared to the cytoplasm. Although none of the cells show exclusion of the EYFP protein from the nucleus, the fusion of HDB to EYFP resulted in two-thirds of the expressing cells showing reduced nuclear protein levels (Fig. 3Aa and b). Inhibition of protein synthesis for 4 h resulted in nearly all of the expressing cells showing reduced nuclear fusion protein levels (Fig. 3Ac). In contrast, blocking proteasome activity significantly reduced the exclusion of nuclear fusion proteins (Fig. 3Ad). Blocking both protein synthesis and proteasome activity for 4 h reduced nuclear exclusion even further (Fig. 3Ae). Removing MG-115 after 2 h restored high levels of nuclear exclusion (Fig. 3Af). We also noted that the number of cells expressing the HDB fusion protein was reduced in this latter experiment. To investigate this further, we compared untreated CV-1 cells with those treated with a cycle of drugs, first both cycloheximide and MG-115 for 2 h, then only cycloheximide for 2 h, and then repeating these treatments before fixing and examining the cells. Fewer cells showed signs of nuclear exclusion (Fig. 3Ag); however, expression levels were low, and the number of cells expressing the fusion protein was reduced by 80%. These results are consistent with the proteasome dependent degradation of nuclear EYFP-HDB. In the absence of protein synthesis, cytoplasmic protein diffuses into the nucleus where it is degraded. Alternatively, cytoplasmic protein may also be degraded but with slower kinetics than that seen for nuclear protein.

Molecular modeling of the Prospero homeodomain.

The sequence of the Prospero homeodomain is highly conserved. Comparing Prospero homeodomain sequences from fly, worm, zebra fish, chicken, mouse, and human sources revealed that 37 of 64 amino acids are invariant. This is comparable to the Prospero domain, where 42 of 100 amino acids are invariant (7). The conservation among more distant homeodomains is much less highly conserved. For example, comparison of the Drosophila En and yeast Mat α2 homeodomains with that of Prospero revealed only 6 of 64 absolutely conserved residues (Fig. 4A).

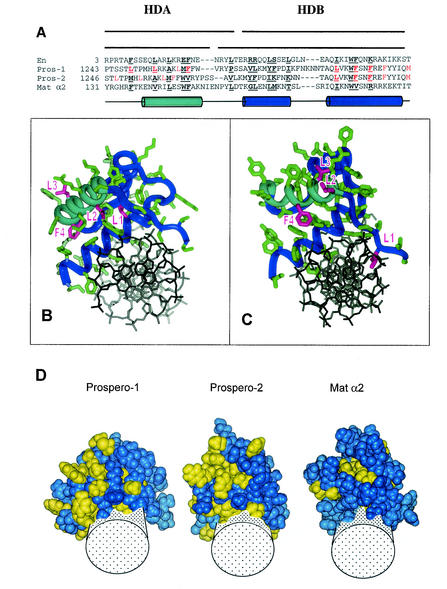

FIG. 4.

Two molecular models of the Prospero homeodomain suggest alternative mechanisms for regulating nuclear export. Prospero models were built by using known three-dimensional structures of the Engrailed (En) and Mat α2 homeodomains, with pdb codes 1HDD and 1APL, respectively (20, 37). (A) Two sequence alignment, Pros-1 and Pros-2, lead to two structural models. Hydrophobic residues mutated and tested below are in red. Helix 1, which is included in HDA, is in light blue, while helices 2 and 3, which are included in HDB, are in dark blue. Interior residues forming the homeodomain's hydrophobic core are underlined. (B and C) Molecular model of the two predicted structures, Prospero-1 and Prospero-2, respectively (blue ribbons), bound to DNA (black sticks). (B) Prospero-1 has the side chains (in purple) of two of three leucine residues, L1 and L2, as well as a phenylalanine, F4, buried inside of the structure, whereas L3 is exposed on the surface. The remaining residues are in green. (C) Prospero-2 has the side chain from L1 buried through an interaction with DNA, while those of L2, L3, and F4 are exposed on the surface. (D) An unusually large cluster of hydrophobic residues (yellow) is on the surface of the Prospero homeodomain. A space-filling representation of the homeodomains of two Prospero models and Mat α2 are shown. Cylinders indicate double-stranded DNA.

The tertiary structure determined for several homeodomains is also highly conserved, consisting of helix 1, helix 2, turn, and helix 3 (reviewed in reference 12). No tertiary structure data existed for the Prospero homeodomain at the time this study was submitted for publication; however, it was likely to be very similar to other homeodomain structures (1). Using a series of refinement steps (see Materials and Methods) we have modeled the Prospero homeodomain onto a homeodomain structure generated from crystallographic data (20, 37). Of particular note is the unusually high number of apolar residues, compared to the other homeodomains, of the region including helices 1 and 2 (Fig. 4A and D). This abundance of apolar residues caused an ambiguity, resulting in our prediction of two plausible models of the Prospero homeodomain (Fig. 4B and C). The first model (Pros-1) was similar to one proposed by Banerjee-Basu et al. (1). Residues constituting the hydrophobic core of the homeodomain are indicated. Both models reveal that the functional NES, HDA, includes all of helix 1 and additional amino acids, whereas HDB includes helix 2, turn, and helix 3 (Fig. 4A).

The large number of apolar residues on the surface of the Prospero homeodomain provides an interface, which might serve in protein-protein interactions. While HDB is buried by the folding of the homeodomain, HDA is on the surface and may be able to interact with the export machinery and/or the NES mask while bound to DNA. Exportin-dependent NESs often consist of precisely spaced hydrophobic residues, preferentially leucines (LXXXLXXLXL, where L is leucine and X is any amino acid) (11); however, the spacing of the HDA apolar residues does not match other export signals (LXXXXLXXXXLXF, where F is phenylalanine; Fig. 4A). We have indicated the positions of four of six hydrophobic amino acids (named L1, L2, L3 and F4, according to their order in the sequence; Fig. 4A), which are absolutely conserved among Prospero homeodomains. In the first model, Pros-1, L1, L2, and F4 are located inside the structure, whereas L3 is exposed to the solvent (Fig. 4B). In the second model, Pros-2, L2, L3, and F4 are exposed, and L1 is buried by its contact with DNA (Fig. 4C). The submission of the experimentally determined the three-dimensional structure of the Prospero homeodomain, while the present study was under review, revealed that the crystal structure is more similar to the Pros-1 model than to Pros-2 (J. M. Ryter, C. Q. Doe, and B. W. Matthews, unpublished data).

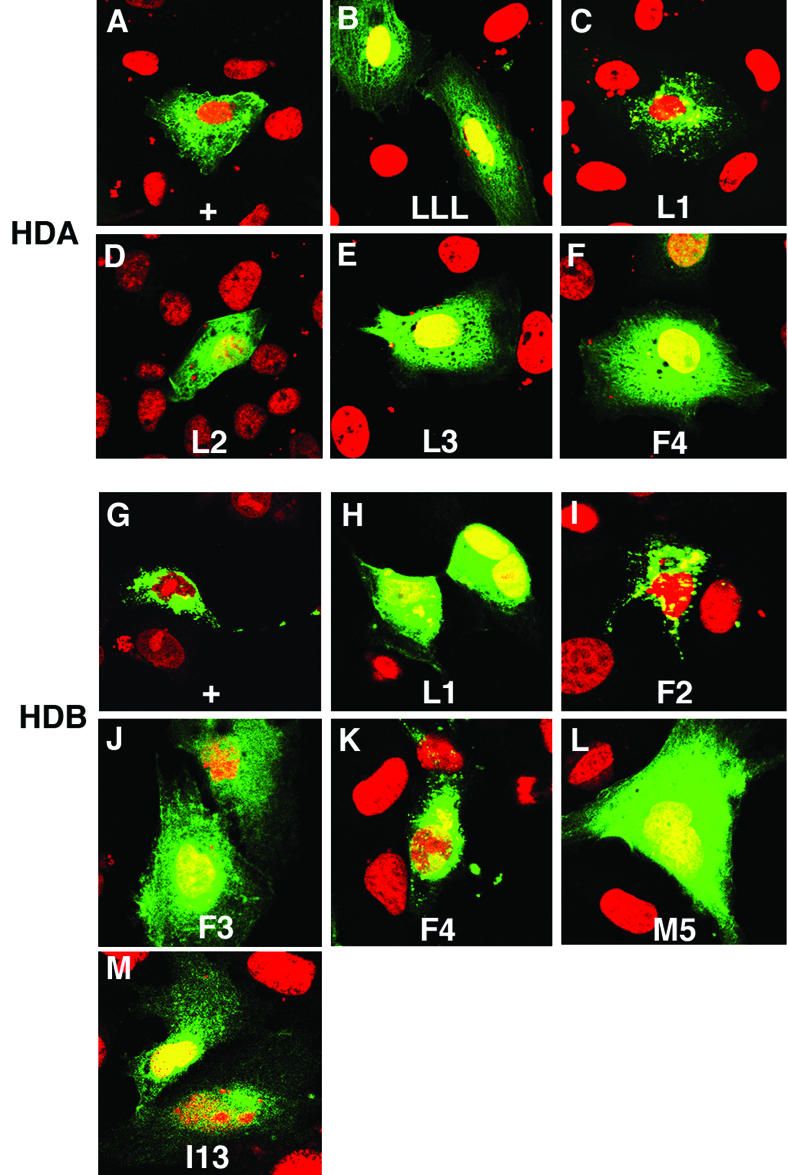

Mutational analysis of HDA and HDB.

In order to identify the residues within HDA and HDB, which are responsible for their functions in altering subcellular localization, we selected specific hydrophobic residues (Fig. 4A) and mutated them to alanine. Fusions between EYFP and mutant HDA were constructed where each leucine individually, all three leucines, or the phenylalanine were mutated to alanine. The expression of these EYFP-mutated HDA constructs was examined after transfection into CV-1 cells. Compared to the wild-type HDA fusion protein, which is excluded from the nucleus (Fig. 5A), mutation of all three leucines restored the ubiquitous nuclear or cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 5B) seen with the vector alone (Fig. 1B). A similar result was observed for individual mutations in the second and third leucines (L2 and L3), as well as in the phenylalanine (F4; Fig. 5D-F). Mutation of the first leucine (L1) had no effect on subcellular localization (Fig. 5C). Note that all three hydrophobic residues required for nuclear export are predicted by the structural model for Pros-2 to be on the exposed surface of the homeodomain (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 5.

Identification of conserved amino acids required for HDA and HDB to exclude fusion protein from the nucleus. (A to L) CV-1 cells transfected with wild-type or mutant pEYFP-HDA (A to F) and pEYFP-HDB (G to L) were analyzed as in Fig. 1. Residues shown in Fig. 4A (red) were mutated to alanine. In HDA, mutation of all three leucines (LLL), the second or third leucine (L2 and L3), or phenylalanine (F4) abrogated nuclear export. Mutation of the first leucine (L1) had no effect on export. In HDB, mutation of leucine (L1), the second phenylalanine (F3), or methionine (M5) abrogated nuclear exclusion. Mutation of the first or third phenylalanine (F2 or F4) had no effect on exclusion. (L) HDB, mutated to carry the same substitutions found in prosI13, abrogated nuclear exclusion.

A similar mutational analysis was performed on the 36-amino-acid HDB sequence. We selected five hydrophobic residues (named L1, F2, F3, F4 and M5, where “M” referes to methionine; Fig. 4A) in HDB which are absolutely conserved among all known Prospero homeodomains and mutated them to alanine. Compared to the wild-type HDB fusion protein, which is excluded from the nucleus (Fig. 5G), mutation of L1, F3, or M5 abrogated exclusion from the nucleus (Fig. 5H, J, and L). Mutation of either F2 or F4 had no effect on subcellular localization (Fig. 5I and K). Both structural models predict that the residues required for nuclear exclusion are buried (Fig. 4B and C).

HDB fusion to EYFP targets it for degradation.

CV-1 cells were cotransfected with pEYFP and either pEYFP-HDB or pEYFP-HDB-F3. The relative stability of the fusion proteins was then compared with the cotransfected EYFP. When the cells were transfected at an equal molar ratio, it was difficult to measure the level of both fusion proteins because they were much less abundant than EYFP (data not shown). We then transfected three times more fusion protein construct than pEYFP. The resulting protein was then analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 3B). Four observations were made about the resulting protein levels. First, the steady-state levels of both EYFP-HDB and EYFP-HDB-F3 relative to EYFP were greatly reduced. Second, EYFP-HDB-F3 was 10 to 20% more abundant than EYFP-HDB (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 4). Third, both EYFP-HDB and EYFP-HDB-F3 were significantly less stable than EYFP since blocking protein synthesis for 2 h results in more degradation of EYFP-HDB and EYFP-HDB-F3 than EYFP (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 5). Assuming EYFP levels are steady during these 2 h, we estimate that as much as 40% of both EYFP-HDB and EYFP-HDB-F3 was degraded in 2 h. Fourth, blocking proteasome activity for 2 h increased the levels of both EYFP-HDB and EYFP-HDB-F3 relative to EYFP (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 6). We conclude that fusing the HDB fragment to EYFP decreases the fusion protein's stability and that this is dependent upon proteasome activity.

prosI13 is a missense mutation that encodes a constitutively cytoplasmic protein missing the Prospero domain.

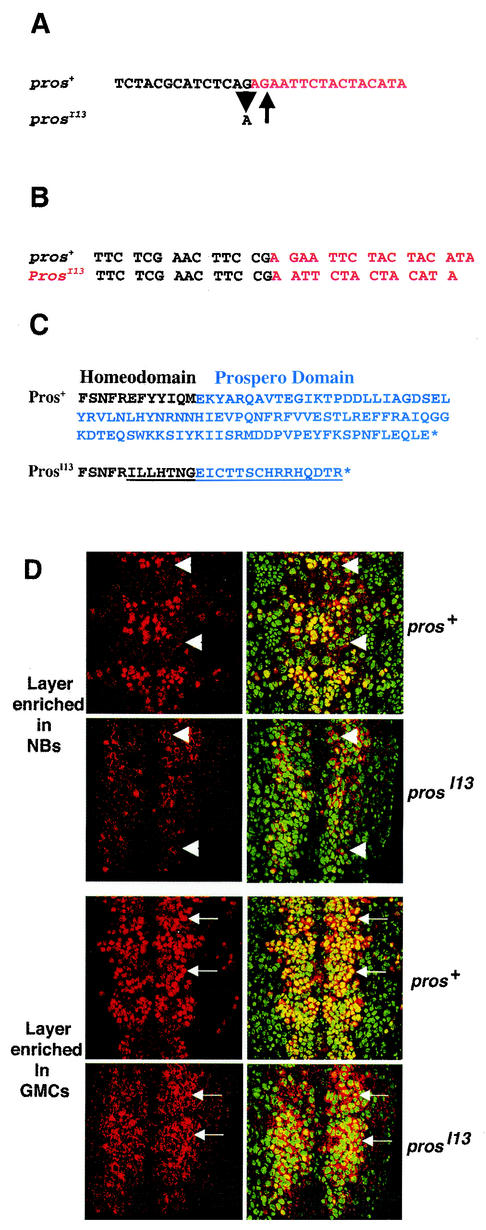

We had previously shown that the Prospero domain is required for masking nuclear export directed by the homeodomain, since the prosS8 allele (19, 29) produces a truncated protein that is constitutively cytoplasmic in Drosophila embryos and in tissue culture cells (7). A second pros allele, prosI13, has also been reported to encode a protein that is constitutively cytoplasmic in embryos (34). We predicted that this allele would also result from a mutation that disrupts the NES mask in the carboxy-terminal Prospero domain. We sequenced genomic DNA from homozygous prosI13 embryos and identified one nucleotide change (Fig. 6A). The G-to-A transition is in the normal splice acceptor AG sequence of the large 13.5-kb intron, which is located in the region encoding the carboxy terminus of the homeodomain (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 6.

Incorrect splicing of prosI13 causes a frameshift mutation with the resulting protein lacking the Prospero domain and relocating it to the cytoplasm of ganglion mother cells. (A) Genomic sequence of prosI13 has a G-to-A transition (arrowhead) at the splice acceptor site of the 13.5-kb intron in the homeodomain (see Fig. 1A). The arrow shows the predicted site of a new splice acceptor site. A partial intron sequence is shown in black; an exon sequence is shown in red. (B) cDNA sequence of prosI13 is missing the nucleotides AG. Sequence from reverse transcription-PCR products of prosI13/TM3 ftz-lacZ pros+ embryonic RNA with the 5′exon sequence shown in black and the 3′ exon sequence shown in red. (C) Predicted protein sequences encoded by the pros+ and prosI13 alleles. The carboxy terminus of the Pros+ protein is shown, including 12 amino acids of the homeodomain (black) and all 100 amino acids of the Prospero domain (blue). The C terminus of ProsI13 protein is predicted to contain a missense sequence (underlined) starting 7 amino acids from the end of the homeodomain and extending 15 amino acids into the Prospero domain until it reaches a stop codon. (D) The ProsI13 protein is exclusively cytoplasmic in nueroblasts (NBs, arrowheads) and largely cytoplasmic in ganglion mother cells (GMCs, arrows). Prospero is shown in red, and the DNA is shown in green. Anterior is up. Two focal planes of late stage 11 wild-type (pros+) and mutant (prosI13) embryos are shown. The first highlights a level enriched in NBs, and the second, ca. 3 μm deeper, is enriched in ganglion mother cells. Embryos were identically stained and photographed. The yellow staining in prosI13 embryos may represent residual nuclear Pros protein or bleed-through from adjacent layers.

Immediately 3′ of the mutation is a second AG sequence, which we hypothesized would be used as a new splice acceptor site, creating a two-nucleotide deletion in the prosI13 mRNA. To test this, we reverse transcribed RNA from heterozygous prosI13/pros+ embryos. The resulting cDNA was then amplified and sequenced. This confirmed that the prosI13 allele utilizes the remaining AG as a splice acceptor site, resulting in its mRNA missing two nucleotides found in the wild-type sequence (Fig. 6B). Thus, the ProsI13 protein will diverge from the wild type, seven amino acids before the end of the homeodomain, with this plus the entire Prospero domain being replaced by a missense sequence extending 15 amino acids into the Prospero domain (Fig. 6C).

We compared the localization and relative abundance of Prospero protein in prosI13 homozygous embryos compared to heterozygous wild-type sibling embryos. Embryos from the same stock used in the reverse transcription-PCR experiment were stained for Prospero, DNA, and β-galactosidase. The latter is expressed in a striped pattern as a result of the ftz-lacZ insertion on the balancer chromosome and was used to mark embryos that were not homozygous mutant. During embryogenesis, neuroblasts delaminate from the neuroectoderm layer on the surface of the embryo and migrate to a deeper layer. These in turn divide to produce ganglion mother cells, which reside deeper than most neuroblasts. By using a confocal microscope, we have focused down through the ventral surface of the embryo to first visualize a layer enriched in neuroblasts and then a layer enriched in ganglion mother cells (Fig. 6D).

A focal plane enriched in neuroblasts shows comparable levels of cytoplasmic Prospero protein in pros+ and prosI13 embryos (Fig. 6D, arrowheads). A deeper focal plane reveals more ganglion mother cells. In pros+ embryos, the yellow-appearing overlap of the DNA, visualized in red, and Pros, visualized in green, shows that Prospero protein is nuclear in wild-type ganglion mother cells. In prosI13 embryos there are significantly fewer yellow-appearing cells, since the mutant ganglion mother cells show predominantly cytoplasmic Prospero protein, seen as red (Fig. 6D). We conclude that most of the Prospero protein is cytoplasmic in prosI13 embryos, confirming an earlier report (34). The residual yellow staining in prosI13 embryos might represent a low level of Prospero protein in the nucleus or bleed through from adjacent focal planes.

The prosI13 mutation changes seven amino acids at the carboxy terminus of the HDB into missense sequence, along with 15 amino acids of the Prospero domain (Fig. 6C). This includes the methionine residue that, when mutated to alanine, abrogates changes in the subcellular localization of HDB fusion proteins (Fig. 5L). We engineered a protein fusing EYFP to the HDB subdomain from the prosI13 mutation. The prosI13 mutation abrogates nuclear exclusion caused by wild-type HDB (Fig. 5M).

The integrity of the homeo/Prospero domain is required for the NES masking function.

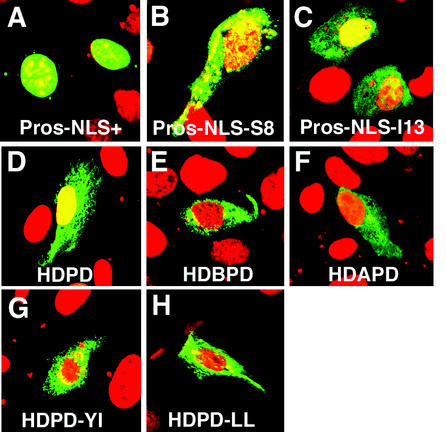

We have now identified two mutations, prosS8 and prosI13, in embryos, which mutate the Prospero domain and result in the accumulation of cytoplasmic but little or no nuclear Prospero protein (Fig. 6D) (7). To investigate the molecular effects on the Prospero protein caused by the mutations responsible for prosS8 and prosI13, we created an EYFP fusion construct beginning amino terminal to the Prospero NLS and extending to the normal Prospero termination codon (Table 1). A single nucleotide substitution was then introduced to create a second construct (see Materials and Methods), this one with the mutation responsible for prosS8. We also deleted the two nucleotides missing in the prosI13 cDNA, creating a third fusion construct resembling prosI13 (Table 1). These were transfected into CV-1 cells and examined by immunohistochemistry. Pros-NLS+ is largely nuclear, with every expressing cell showing enrichment of the protein in the nucleus (Fig. 7A). In contrast, Pros-NLS-S8 is no longer localized primarily to the nucleus and is often excluded (Fig. 7B), confirming that the NES mask is not functioning. Pros-NLS-I13 is more variable than Pros-NLS-S8, with the protein slightly enriched in the nucleus in ca. 20% of expressing cells but ubiquitous or de-enriched in the nucleus of the remaining 80% of expressing cells (Fig. 7C). There appear to be more Pros-NLS-I13- than Pros-NLS-S8-expressing cells in parallel experiments, suggesting that the stability of Pros-NLS-I13 is greater than Pros-NLS-S8; however, since there is no internal control for transfection efficiency, we cannot be sure of the cause of this difference. There is also an even more pronounced increase in the number of Pros-NLS+-expressing cells.

FIG. 7.

The intact homeo/Prospero domain is required for NES masking. (A) Wild-type Pros-NLS+ includes 392 amino acids beginning just amino terminal to the Prospero NLS and extending to the Prospero stop codon (see Table 1) fused to pEYFP. (B and C) Pros-NLS-S8 and Pros-NLS-I13 contain the same changes responsible for prosS8 and prosI13. (A to C) Although CV-1 cells express exclusively nuclear Pros-NLS+ (A), most Pros-NLS-S8- and Pros-NLS-I13-expressing cells do not show enrichment of the fusion protein in the nucleus (B and C). (D) Wild-type pEYFP-HDPD is not excluded from the nucleus. (E and F) Deletion of HDA (E) or HDB (F) from the homeo/Prospero domain abrogates mask function, visible as exclusion of fusion proteins from the nucleus. (G and H) Point mutations changing the indicated amino acids in the C terminus of the HD (HDPD-YI) to proline (G) or the N terminus of the PD (HDPD-LL) to alanine (H), abrogate NES masking function. CV-1 cells were transfected and analyzed as in Fig. 1.

To investigate the stability of the proteins encoded by these new constructs, we performed a cotransfection experiment with equal ratios of pEYFP and Pros-NLS+, Pros-NLS-S8 or Pros-NLS-I13. The resulting protein was analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 3C). First, the sizes of Pros-NLS-S8 and Pros-NLS-I13 are slightly reduced in comparison with Pros-NLS+, as predicted from the sequence changes in the prosS8 and prosI13 mutations. Second, the Pros-NLS+ fusion protein is significantly more stable than either Pros-NLS-S8 or Pros-NLS-I13. Third, the Pros-NLS-I13 protein is more stable than Pros-NLS-S8. These results are consistent with Pros-NLS-S8 retaining both an export signal (HDA) and a nuclear degradation signal (HDB), whereas Pros-NLS-I13 retains the export signal but has an impaired nuclear degradation signal.

We had also previously shown that deletion of any third of the Prospero domain (PDA, PDB, and PDC; Fig. 1A) resulted in constitutive nuclear export in tissue culture cells (7). To define all of the regions of the homeo/Prospero domain required for NES mask function, we created two additional deletions, removing either HDA or HDB from the HDPD construct (HDBPD or HDAPD, respectively). Expression of these fusion proteins in CV-1 cells revealed that they are also required for masking function, since the proteins are excluded from the nucleus (Fig. 7D to F).

Our next mutations were based on our secondary structure predictions. These suggest that the homeo/Prospero domain is highly helical, including a helix predicted to extend beyond helix 3 of the homeodomain into the beginning of the Prospero domain (data not shown). We next introduced mutations, which are expected to alter the helical stability of the junction between the homeodomain and the Prospero domain. Two of the mutations in the carboxy terminus of the homeodomain change an adjacent tyrosine and isoleucine into prolines (HDPD-YI) and result in the cytoplasmic localization of the fusion protein (Fig. 7G). A second pair of mutations was induced in the amino terminus of the Prospero domain, mutating two leucines into alanines (HDPD-LL) and resulting in the cytoplasmic localization of the fusion protein (Fig. 7H). The homeo/Prospero domain crystal structure, which has recently become available (Ryter et al., unpublished), shows that our assumption about the extended helix 3 was correct. In summary, the integrity of the homeo/Prospero domain is required for the masking of the two nuclear exclusion functions described above.

DISCUSSION

We have used a combination of transient-transfection assays, mutational analysis, and inhibitor studies to investigate the effects of different regions in the homeo/Prospero domain on the protein's subcellular localization. Our observations are similar to those made while studying two pros mutations in embryos (Fig. 6) (7) and suggest mechanisms for the regulation of Prospero function. Three observations were made. First, the HDA region acts as an Exportin-dependent NES as it is inhibited by the drug leptomycin B (Fig. 1A and C and 2A and D) (7). Second, the HDB region acts as a proteasome-dependent nuclear degradation signal as it is inhibited by the drugs lactacystin and MG-115 (Fig. 1A and D and 2B and H). Third, the complete homeo/Prospero domain masks these nuclear exclusion functions (Fig. 7D to H). These three functions are sequence specific since point mutations in some of the conserved amino acids abrogate each of them (Fig. 5 and 7). Additional domains in Prospero affect the subcellular localization of the protein (Fig. 1A), including the asymmetric localization domain, which functions as a cytoplasmic tether (18, 32) and an NLS (28).

Structural predictions of the homeo/Prospero domain elucidate nuclear exclusion regulatory mechanisms.

No structural data existed for the homeo/Prospero domain at the time this study was submitted for publication, although the tertiary structure of several homeodomains had been determined (reviewed in reference 12). In order to understand the relationship between the DNA binding and nuclear exclusion functions of the homeodomain, we modeled the Prospero homeodomain onto structures for En and Mat α2 (Fig. 4B and C) (20, 37). Because of the high number of apolar residues in Prospero, our alignment predicts two equally probable structures. Both result in an unusually hydrophobic surface compared to other homeodomains (Fig. 4D). This surface is a likely interface for intra- and/or intermolecular protein-protein interactions. The new crystal structure of the Prospero homeodomain (Ryter et al., unpublished) resembles our first model (Fig. 4B).

Our alignments delimit the HDA export signal to a region including helix 1 and the HDB proteasome-dependent nuclear exclusion signal to a region including helices 2 and 3 of the homeodomain. Both models show that the three residues essential for HDB directed nuclear exclusion (L1, F3, and M5; Fig. 5H, J, and L) are buried. Two (L1 and F3) make up the hydrophobic core of helix 3 (Fig. 4A to C). This may explain why HDB is usually suppressed in constructs including the entire homeodomain (Fig. 2). In contrast, specific residues in HDA occur on the surface of the homeodomain; therefore, it might be possible for Exportin pathway proteins to initiate nuclear export even while the protein is bound to DNA (Fig. 4C).

The two putative structures of the Prospero homeodomain predict markedly different mechanisms for the regulation of Prospero nuclear export. We have underlined the amino acids making up the hydrophobic core of the homeodomain and highlighted those tested in our mutational analysis in red (Fig. 4A). Three of four conserved hydrophobic residues in HDA abrogate nuclear export when mutated to alanine (Fig. 5A to F). In the experimentally determined structure, as well as in our model labeled Pros-1, two of the amino acids essential for export, L2 and F4, are part of the hydrophobic core, along with L1, which was not required for NES function. Thus, the export signal is inaccessible in this configuration (Fig. 4A and B). In the second model, labeled Pros-2, none of the three amino acids required for NES function is part of the hydrophobic core; all are exposed on the surface of the homeodomain and are accessible for interactions with the export machinery (Fig. 4A and C). A regulatory step that triggers nuclear export of a protein with the structure of Pros-2 will only have to unmask the signal; however, a protein with the conformation of the known crystal structure (Pros-1) will require unmasking as well as changing the conformation of the export signal. Note that the conformational change of Pros-1 might be into that of Pros-2 by rearrangement of the amino-terminal HDA subdomain.

The Prospero domain is unique to Prospero and its homologs (4). The crystal structure of the Prospero homeodomain revealed an extended helix 3 connecting the homeodomain and Prospero domain (Ryter et al., unpublished). While nuclear exclusion is masked in fusion constructs with an intact homeo/Prospero domain, mutations that disrupt the helical continuity between the homeodomain and the Prospero domain abrogate the masking function (Fig. 7D and E). The most parsimonious explanation is that the structure of the homeo/Prospero domain results in masking of the nuclear exclusion signals of the protein. The molecular signal for unmasking the nuclear exclusion domains remains to be identified.

Comparison of our structural predictions with a new crystal structure.

While this study was in review, we received a copy of a manuscript by Ryter et al. describing the crystal structure of the homeodomain and the Prospero domain (Ryter et al., unpublished). That study provided us with an opportunity to assess the validity of our structural predictions. The comparison showed that the crystal structure is similar to our Pros-1 model, whereas Pros-2 is significantly different, especially in the amino-terminal HDA region. The ambiguity in the prediction of the HDA region originated from its unusually high proportion of hydrophobic residues.

The crystal structure confirms a number of predictions from our combined approach of molecular modeling and mutational analysis. First, we predicted that the Prospero domain would be highly helical. The crystal structure shows the Prospero domain forming a four-helix bundle. Second, we predicted that the third helix of the homeodomain would extend into the Prospero domain and that the integrity of this connection would maintain the masked confirmation of the NES. The crystal structure demonstrates that helix 3 of the homeodomain does extend into the Prospero domain. Third, we predicted that the HDA NES would be on the surface of the homeodomain and might be masked by directly interacting with the Prospero domain. The crystal structure suggests that some of the residues required for nuclear export might be buried, as predicted by our Pros-1 model; however, the phenylalanine residue required for nuclear export (F4, Fig. 4 and 5) is demonstrated to reside on the boarder of helix 1, in a position near the Prospero domain. Thus, the crystal structure supports our prediction that masking might result from a direct interaction of the export signal and the mask. Fourth, the crystal structure suggests that the HDA NES is inaccessible to interactions with the export machinery. We suggest that the crystal structure is in the masked conformation and that a regulatory step that triggers the unmasking of the NES might include changing the conformation of the amino-terminal HDA subdomain from the one observed in the crystal structure to the conformation suggested in our Pros-2 model.

What is the in vivo requirement for nuclear export and degradation?

Evidence supporting the requirement for nuclear degradation, export, and their masking in the formation of the embryonic nervous system remains circumstantial. However, the weight of the evidence suggests that there exists a complex set of regulatory steps to control the subcellular localization of Prospero.

There is extensive homology among the homeo/Prospero domains from worms to humans but very little conservation outside of this region (4, 13, 30, 35, 38). The homeodomain functions as a DNA-binding domain (reviewed in reference 12). The function of the Prospero domain is inferred from mutational analyses. First, prosS8 results in a protein missing the carboxy-terminal 30 amino acids from the Prospero domain, which accumulates constitutively in the cytoplasm of ganglion mother cells, even though it has a functional NLS (7). Here we showed that a second mutation, prosI13, also results in constitutively cytoplasmic Prospero protein lacking the Prospero domain (Fig. 6). This suggested three plausible functions for the Prospero domain. It might be a: (i) strong NLS, (ii) nuclear tether, or (iii) nuclear exclusion mask.

These hypotheses were tested with transiently transfected tissue culture cells. Inclusion of the Prospero domain, in proteins lacking the homeodomain, has no effect on the protein's subcellular localization (Fig. 1E to G; data not shown). Therefore, the Prospero domain does not function as an NLS. Deletion of either the 28 amino acids from the beginning (Fig. 7B; HDBPD) or the 36 amino acids from the end (Fig. 7C; HDAPD) of the homeodomain in constructs including an intact Prospero domain results in nuclear exclusion of the protein. Therefore, the Prospero domain does not function as a nuclear tether. Finally, leptomycin B treatment of cells expressing proteins including either the first 28 amino acids of the homeodomain (HDA) or the full homeodomain restores nuclear localization (Fig. 2) (7). Lactacystin or MG-115 treatment of cells expressing proteins, including the carboxy-terminal 36 amino acids from the homeodomain (HDB), also restores nuclear localization (Fig. 2). Since the homeodomain has a functional Exportin-dependent NES (HDA) and a proteasome-dependent nuclear exclusion signal (HDB), the Prospero domain's primary function is to mask nuclear exclusion.

A major role in cytoplasmic localization is played by the adaptor protein, Miranda, which tethers Prospero to the basal cortex of neuroblasts (18, 32). However, in embryos lacking Miranda, Prospero is also initially found in the neuroblast cytoplasm (18), even though the protein includes an NLS (28). Nuclear export may facilitate this cytoplasmic localization. Miranda becomes undetectable when ganglion mother cells are formed and Prospero translocates into the nucleus (18, 32). Prospero protein lacking an intact Prospero domain remains in the cytoplasm of ganglion mother cells, most likely because of Exportin-dependent nuclear export and proteasome-dependent nuclear degradation. While it is unclear whether these latter effects are part of normal determination of ganglion mother cell versus neuroblast cell fate, the effects are likely to identify regulatory steps required later in nervous system differentiation. For example, when ganglion mother cells divide to produce neurons, Prospero protein becomes undetectable. Likewise, Prospero protein disappears from newly formed neurons shortly after their formation in the external sensory organ precursor lineage and during the formation of the chordotonal organs of the peripheral nervous system. We propose that Exportin and proteasomes play roles in these events.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Badenhorst for advice and comments and Chris Doe for prosI13. We also thank J. M. Ryter, C. Q. Doe, and B. W. Matthews for a copy of their manuscript prior to its publication and Y. Bai, D. Chattoraj, and W. Odenwald for helpful comments. MR1A (33) was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by the University of Iowa Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerjee-Basu, S., D. Landsman, and A. D. Baxevanis. 1999. Threading analysis of Prospero-type homeodomains. In Silico Biol. 1:163-173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks, B. R., R. E. Bruccoleri, B. D. Olafson, D. J. States, S. Swaminathan, and M. Karplus. 1983. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comp. Chem. 4:187-217. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucher, P., K. Karplus, N. Moeri, and K. Hofmann. 1996. A flexible motif search technique based on generalized profiles. Comput. Chem. 20:3-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burglin, T. R. 1994. A Caenorhabditis elegans prospero homologue defines a novel domain. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19:70-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu-Lagraff, Q., D. M. Wright, L. K. McNeil, and C. Q. Doe. 1991. The prospero gene encodes a divergent homeodomain protein that controls neuronal identity in Drosophila. Dev. Suppl. 2:79-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayring, H. E., A. Tramonato, S. R. Sprang, and R. J. Fletterick. 1986. Interactive program for visualization and modeling of proteins, nucleic acids and small molecules. J. Mol. Graph. 4:82-87. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demidenko, Z., P. Badenhorst, T. Jones, X. Bi, and M. A. Mortin. 2001. Regulated nuclear export of the homeodomain transcription factor Prospero. Development 128:1359-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dick, L. R., A. A. Cruikshank, L. Grenier, F. D. Melandri, S. L. Nunes, and R. L. Stein. 1996. Mechanistic studies on the inactivation of the proteasome by lactacystin: a central role for clasto-lactacystin beta-lactone. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7273-7276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doe, C. Q., Q. Chu-LaGraff, D. M. Wright, and M. P. Scott. 1991. The prospero gene specifies cell fates in the Drosophila central nervous system. Cell 65:451-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenteany, G., R. F. Standaert, W. S. Lane, S. Choi, E. J. Corey, and S. L. Schreiber. 1995. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science 268:726-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda, M., S. Asano, T. Nakamura, M. Adachi, M. Yoshida, M. Yanagida, and E. Nishida. 1997. CRM-1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature 390:308-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gehring, W. J., M. Affolter, and T. Burglin. 1994. Homeodomain proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63:487-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow, E., and S. I. Tomarev. 1998. Restricted expression of the homeobox gene prox 1 in developing zebrafish. Mech. Dev. 76:175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassan, B., L. Li, K. A. Bremer, W. Chang, J. Pinsonneault, and H. Vaessin. 1997. Prospero is a panneural transcription factor that modulates homeodomain protein activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10991-10996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins, D. G., J. D. Thompson, and T. J. Gibson. 1996. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 266:383-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirata, J., H. Nakagoshi, Y.-I. Nabeshima, and F. Matsuzaki. 1995. Asymmetric segregation of the homeodomain protein Prospero during Drosophila development. Nature 377:627-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hursh, D. A., R. W. Padgett, and W. M. Gelbart. 1993. Cross regulation of decapentaplegic and Ultrabithorax transcription in the embryonic visceral mesoderm of Drosophila. Development 117:1211-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikeshima-Kataoka, H., J. B. Skeath, Y. Nabeshima, C. Q. Doe, and F. Matsuzaki. 1997. Miranda directs Prospero to a daughter cell during Drosophila asymmetric divisions. Nature 390:625-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, W. J., L. P. Burke, and M. A. Mortin. 1994. Molecular modeling of RNA polymerase II mutations onto DNA polymerase I. J. Mol. Biol. 244:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kissinger, C. R., B. S. Liu, E. Martinblanco, T. B. Kornberg, and C. O. Pabo. 1990. Crystal-structure of an engrailed homeodomain-DNA complex at 2.8-A resolution-A framework for understanding homeodomain-DNA interactions. Cell 63:579-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komeili, A., and E. K. O'Shea. 2001. New perspectives on nuclear transport. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:341-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudo, N., S. Khochbin, K. Nishi, K. Kitano, M. Yanagida, M. Yoshida, and S. Horinouchi. 1997. Molecular cloning and cell cycle-dependent expression of mammalian CRM1, a protein involved in nuclear export of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 272:29742-29751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kudo, N., N. Matsumori, H. Taoka, D. Fujiwara, E. P. Schreiner, B. Wolff, M. Yoshida, and S. Horinouchi. 1999. Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9112-9117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kudo, N., B. Wolff, T. Sekimoto, E. P. Schreiner, Y. Yoneda, M. Yanagida, S. Horinouchi, and M. Yoshida. 1998. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal-mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp. Cell Res. 242:540-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laskowski, R. A., M. W. McArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, L., and H. Vaessin. 2000. Pan-neural Prospero terminates cell proliferation during Drosophila neurogenesis. Genes Dev. 14:147-151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning, L., and C. Q. Doe. 1999. Prospero distinguishes sibling cell fate without asymmetric localization in the Drosophila adult external sense organ lineage. Development 126:2063-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuzaki, F., K. Koizumi, C. Hama, T. Yoshioka, and Y. I. Nabeshima. 1992. Cloning of the Drosophila Prospero gene and its expression in ganglion mother cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 182:1326-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mortin, M. A. 1990. Use of second-site suppressor mutations in Drosophila to identify components of the transcriptional machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4864-4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliver, G., B. Sosa-Pineda, S. Geisendorf, E. P. Spana, C. Q. Doe, and P. Gruss. 1993. Prox-1, a prospero-related homeobox gene expressed during mouse development. Mech. Dev. 44:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy, G. V., and V. Rodrigues. 1999. Sibling cell fate in the Drosophila adult external sense organ lineage is specified by Prospero function, which is regulated by Numb and Notch. Development 126:2083-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen, C.-P., L. Y. Jan, and Y. N. Jan. 1997. Miranda is required for the asymmetric localization of Prospero during mitosis in Drosophila. Cell 90:449-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spana, E., and C. Q. Doe. 1995. The Prospero transcription factor is asymmetrically localized to the cell cortex during neuroblast mitosis in Drosophila. Development 121:3187-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srinivasan, S., C. Y. Peng, S. Nair, J. B. Skeath, E. P. Spana, and C. Q. Doe. 1998. Biochemical analysis of prospero protein during asymmetric cell division: cortical Prospero is highly phosphorylated relative to nuclear Prospero. Dev. Biol. 204:478-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomarev, S. I., O. Sundin, S. Banerjee-Basu, M. K. Duncan, J.-M. Yang, and J. Piatigorsky. 1996. Chicken homeobox gene Prox 1 related to Drosophila prospero is expressed in the developing lens and retina. Dev. Dyn. 206:354-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaessin, H., E. Grell, B. Wolff, E. Bier, L. Y. Jan, and Y. N. Jan. 1991. prospero is expressed in neuronal precursors and encodes a nuclear protein that is involved in the control of axonal outgrowth in Drosophila. Cell 67:941-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolberger, C., A. K. Vershon, B. S. Liu, A. D. Johnson, and C. O. Pabo. 1991. Crystal-structure of a mat alpha-2 homeodomain-operator complex suggests a general model for homeodomain-DNA interactions. Cell 67:517-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zinoviev, R. D., M. K. Duncan, T. R. Johnson, R. Torres, M. H. Polymeropoulos, and S. I. Tomarev. 1996. Structure and chromosomal localization of the human homeobox gene Prox 1. Genomics 35:517-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]