Abstract

Two high-affinity, G protein-coupled melatonin receptor subtypes have been identified in mammals. Targeted disruption of the Mel1a melatonin receptor prevents some, but not all, responses to the hormone, suggesting functional redundancy among receptor subtypes (Liu et al., Neuron 19:91-102, 1997). In the present work, the mouse Mel1b melatonin receptor cDNA was isolated and characterized, and the gene has been disrupted. The cDNA encodes a receptor with high affinity for melatonin and a pharmacological profile consistent with its assignment as encoding a melatonin receptor. Mice with targeted disruption of the Mel1b receptor have no obvious circadian phenotype. Melatonin suppressed multiunit electrical activity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in Mel1b receptor-deficient mice as effectively as in wild-type controls. The neuropeptide, pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating peptide, increases the level of phosphorylated cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) in SCN slices, and melatonin reduces this effect. The Mel1a receptor subtype mediates this inhibitory response at moderate ligand concentrations (1 nM). A residual response apparent in Mel1a receptor-deficient C3H mice at higher melatonin concentrations (100 nM) is absent in Mel1a-Mel1b double-mutant mice, indicating that the Mel1b receptor mediates this effect of melatonin. These data indicate that there is a limited functional redundancy between the receptor subtypes in the SCN. Mice with targeted disruption of melatonin receptor subtypes will allow molecular dissection of other melatonin receptor-mediated responses.

The hormone, melatonin, is produced rhythmically in the vertebrate pineal gland (13). Rhythmic melatonin production plays a critical role in the regulation of reproduction in seasonally breeding mammals (1, 24). In nonmammalian vertebrates, melatonin also plays a major role in the regulation of circadian rhythms (4, 46). While endogenous melatonin appears to play only a subtle role in the regulation of circadian rhythms in mammals, exogenous melatonin influences circadian rhythms in several rodent species and in humans (2, 3, 9, 21, 22, 39, 46, 47). While the magnitude of this phase shifting effect is small for adult mammals, it is nevertheless critical in some situations; e.g., daily melatonin administration appears to be useful for entrainment of non-24-h circadian cycles to the 24-hour day for blind individuals (22).

Two high-affinity receptors for melatonin have been identified in mammals (for reviews, see references 33 and 43). These receptors, the Mel1a and Mel1b receptor subtypes, are members of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily (29, 30). A melatonin receptor-related receptor (also called H9 and GPR50) has sequence homology to the Mel1a and Mel1b receptors but does not bind melatonin (7, 16, 32). In addition to these three members of the gene family in mammals, nonmammalian species have a third high-affinity melatonin receptor subtype, the Mel1c receptor (31). The mammalian Mel1a and Mel1b receptors are also called the MT1 and MT2 receptors, respectively [10]. The inability of this MT nomenclature system to accommodate the nonmammalian Mel1c receptor has resulted in persistence of dual nomenclature systems; here, we use the original nomenclature.

The relative importance of the mammalian melatonin receptor subtypes in mediating circadian responses to the hormone is unclear. The circadian clocks of neonatal hamsters are very efficiently set by even a single injection of melatonin, and several physiological and in vitro responses of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) to melatonin have been observed in hamsters (25, 36, 39, 47). Remarkably, however, the Mel1b receptor gene of several hamster species, including those with robust circadian and reproductive responses to the hormone, does not encode a functional melatonin receptor (47; see also GenBank accession number AY145849). Pharmacological studies with mice, however, suggest that the mouse Mel1b receptor mediates circadian responses (9, 19). Other data, derived from mice with targeted disruption of the Mel1a melatonin receptor, indicate that this subtype mediates an acute suppressive effect of melatonin on SCN neuronal firing, and they reveal apparent redundancy of receptor subtypes in mediating the phase shifting response to melatonin (23).

To determine whether the mouse Mel1b receptor contributes to responses to the hormone, the mouse Mel1b receptor cDNA was isolated. Finding that the mouse Mel1b receptor cDNA encodes a high-affinity melatonin receptor, we then disrupted the Mel1b receptor gene. Analysis of the mutant mice indicates that the Mel1b receptor encodes a functionally relevant melatonin receptor. The Mel1b receptor appears to mediate a response to the hormone occurring at higher ligand concentrations in mice lacking the Mel1a melatonin receptor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and characterization of the mouse Mel1b receptor cDNA.

A fragment of the mouse Mel1b receptor cDNA isolated by PCR has been previously reported (47). A probe based on this published sequence was used to screen mouse genomic DNA libraries, resulting in isolation of two overlapping genomic clones containing exon 2 (A341 and A351). Genomic DNA encoding exon 1 was isolated from a bacterial artificial chromosome library (Research Genetics, Inc.) screened with the most 5′ end of the intronic sequence from clone A341. In addition, PCR amplification of mouse brain cDNA was performed using primers spanning the intron, to confirm the splicing pattern, as well as along the cDNA to confirm the sequence. A full-length cDNA was isolated by PCR using an overlap-PCR method to “stitch” together exons 1 and 2, producing a silent mutation at the slice site. The integrity of the cDNA construct was confirmed by sequence analysis and compared to the sequence of genomic clones.

Genomic DNA sequence corresponding to the mouse Mel1b receptor locus has recently been deposited in GenBank. GenBank accession no. NW_000351 represents a genomic contig including the mouse Mel1b receptor locus. The deduced amino acid sequence of the receptor cDNA (GenBank accession no. XM_146818), based on inferred splicing patterns using GenomeScan, differs from that determined above due to the detection of two apparent exons within intron 1, disruption of exon 2 by an apparent intron, and splicing to an additional exon just 5′ of the actual stop codon. Both homology with other members of the melatonin receptor gene family and the RT-PCR data support the conclusion that the Mel1b receptor locus consists of two exons.

When the nucleotide sequences are translated using a two-exon model, the deduced amino acid sequence of the Mel1b receptor cDNA reported in GenBank (AAL85489 and NW_000351) still differs from our sequence, due to the apparent insertion of two nucleotides in exon 2 in the portion of sequence encoding the carboxyl terminus of the protein in the GenBank entry. The accuracy of the sequence reported here is supported by homology of our deduced amino acid sequence with the human and Northern pike Mel1b receptor sequences (12) and is confirmed by the identity of our sequence with the sequence entry in the Celera database (entries mCT7575 and mCG8325). (The only amino acid difference between the sequence reported here and in the Celera database is T237 of our sequence, which is E237 in the Celera and other sequences.) We cannot exclude the possibility that strain differences or other polymorphisms in the genetic sequence exist.

Ligand binding characteristics.

To compare the affinity and specificity of the mouse Mel1a and Mel1b receptors, the characteristics of these receptor cDNAs were examined in parallel in transiently transfected COS7 cells. Ligand binding studies were conducted using the radioligand 2-[125I]iodomelatonin (125I-MEL) as previously described (29, 34). Saturation binding experiments were conducted with ligand concentrations ranging from 10 to 1,800 pM. Data were analyzed using Kaliedograph software. Competitive inhibition studies were conducted using 125I-MEL concentrations of 110 to 150 pM. Ki values were calculated from 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values using the Cheng-Prusoff equation (5): Ki = IC50/(1 + ([ligand]/Kd)).

Targeting disruption of the Mel1b receptor gene.

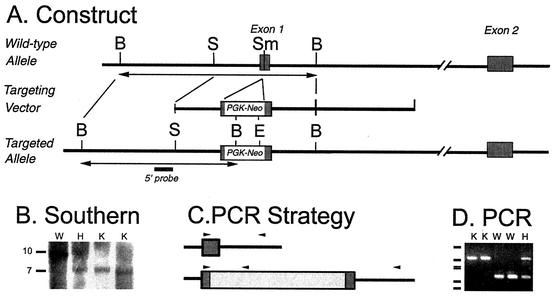

A targeting construct was generated in which the first exon of the Mel1b receptor gene was disrupted by insertion of a neomycin resistance cassette at a SmaI site in exon 1 (Fig. 1). The cassette (PGK-Neo) consists of the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter and a neomycin resistance gene and was placed in reverse orientation. The 5′ arm was 2.2 kb; the 3′ arm was 7 kb. The targeting construct was introduced into J1 embryonic stem cells by electroporation at the Massachusetts General Hospital Knockout Core facility (En Li, director). For screening, DNA from neomycin-resistant colonies was digested with BamHI and assessed by Southern blotting, using a nonoverlapping 0.8-kb SstI fragment flanking the 5′ end of the construct as a probe. The targeting event was confirmed by digestion of embryonic stem cell DNA with EcoRI, followed by hybridization with a nonoverlapping probe (based on exon 2) from the 3′ flanking region as a probe (data not shown). A clone with the appropriate banding pattern on Southern blot analysis (#83) was microinjected into blastocysts by the Knockout Core facility. Chimeric mice were bred to females of strain 129/sv, provided by En Li. Heterozygous offspring were bred together to generate isogenic Mel1b receptor-deficient and wild-type lines on the 129/sv background.

FIG. 1.

Mel1b receptor gene, targeting construct, and genotyping strategies. (A) Schematic of the Mel1b receptor gene and the targeting construct. A neomycin resistance gene driven by the phosphoglycerate kinase promoter (PGK-Neo cassette) was inserted in reverse orientation at the SmaI site within exon 1 of the mouse Mel1b receptor gene. The 5′ and 3′ arms of the targeting construct were 2.2 and 7 kb, respectively. (B) Genotyping by Southern blot. A BamHI restriction site introduced with the PGK-Neo cassette formed the basis for genotyping by Southern blotting, using a probe (solid bar in panel A) located outside the 5′ end of the construct. Following digestion with BamHI, the probe hybridizes to a ca. 10-kb band in wild-type DNA and a ca. 7-kb band for the targeted allele. Genotypes are shown above the lanes. Lanes illustrate the hybridization pattern of wild-type (W), heterozygous mutant (H), and homozygous Mel1b-receptor mutant (knockout [K]) mice. Approximate sizes of the genomic fragments are indicated at the left. (C) Strategy for genotyping by PCR. Magnified view of the relationship of the primers (arrows) to the nucleotide sequences of the Mel1b receptor gene and the PGK-Neo cassette. (D) Genotyping by PCR. Amplification of mouse genomic DNA with a cocktail of three primers led to amplification of distinct bands representing the wild-type and targeted alleles. Genotypes are shown above the lanes; designations are as in panel B. Size markers on the left indicate bands at 910, 540, 426, 409, 266, and 166 bp, generated by pUC19 and digested with DdeI.

Southern blot analysis of tail DNA confirmed the targeting event (Fig. 1B). For colony maintenance, mice were genotyped using PCR (Fig. 1C and D). Reactions were performed using a mixture of three primers, allowing detection of both wild-type and targeted alleles in a single reaction (Fig. 1C). A common forward primer in exon 1 (mus1b5′-4, CCAGGCCCCCTGTGACTGCCCGGG) and a gene-specific reverse primer from intron 1 (mus1b3′-3, 5′ CCTGCCACTGAGGACAGAACAGGG 3′) amplified a 272-bp fragment from the wild-type allele. The common forward primer and a reverse primer based on the sequence of the 3′ end of the PGK-Neo cassette (neo6-2, TGCCCCAAAGGCCTACCCGCTTCC) amplified a ca. 550-bp fragment from the targeted allele. Amplification of genomic DNA extracted from tail biopsies was performed using Taq DNA polymerase and a program of 3 min at 94°C for initial denaturation, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C (30 s), annealing at 60°C (30 s), and extension at 72°C (1 min). Products were separated on agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide using UV trans-illumination (Fig. 1D).

Generation of melatonin receptor-deficient lines on a C3H/He genetic background.

Mice with targeted disruption of the Mel1a receptor have been previously described (23). In these mice, exon 1 of the Mel1a receptor gene has been replaced with the PGK-neomycin cassette. To generate animals with the receptor targeting events on a consistent genetic background, a Mel1a receptor-deficient male mouse with a hybrid, 129/sv × C57BL/6 genetic background was backcrossed to a C3H/He strain female (C3H, Charles River Laboratories). The C3H strain was used because this strain has been used extensively by others in examining circadian behavioral responses to melatonin (2, 3, 9), and this strain has rhythmic melatonin production (unlike most other inbred strains of mice; see reference 11). In each generation, heterozygous males were selected and crossed to C3H females. After backcrossing was done for 10 generations, heterozygous male and female mice were interbred to produce wild-type and Mel1a receptor-deficient lines which produce rhythmic melatonin as previously reported (42).

Similarly, a male Mel1b receptor-deficient mouse (on the isogenic, 129/sv genetic background) was bred to a C3H female. Heterozygous male offspring from each generation were backcrossed to C3H females for six generations of backcrossing, at which time male and female heterozygotes were interbred to produce wild-type and Mel1b receptor-deficient lines on the C3H background. Finally, Mel1a receptor-deficient mice on the C3H genetic background were crossed with the Mel1b receptor-deficient mice on the C3H background to generate Mel1a/Mel1b double-mutant mice on a C3H genetic background.

Multiunit recordings.

Multiunit recordings of SCN electrical activity were performed as previously described (14, 23). Briefly, hypothalamic slices were prepared from adult male mice maintained in a 12-h light:12-h dark lighting cycle. Animals were euthanatized 2 to 5 h after lights-on. Brains were rapidly dissected and placed into artificial cerebrospinal fluid medium (ACSF) containing 116.3 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.0 mM NaH2PO4, 26.2 mM NaHCO3, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 24.6 mM dextrose, and 5-mg/liter gentamicin sulfate (pH 7.5). Slices (400 μm thick) were prepared using a tissue chopper. Electrical activity was recorded using a Teflon-coated platinum-iridium wire electrode as previously described (14, 23).

Experiments were performed on the second day in vitro, >24 h after preparation of the slices. Slices were exposed to vehicle (0.1% ethanol in ACSF) and then to escalating concentrations of melatonin (0.1 to 100 nM) in ACSF containing a maximum of 0.1% ethanol. Data are expressed as percent change in electrical activity at the 100-nM dose. Experiments were conducted without knowledge of the genotypes of the animals. These studies were conducted on wild-type and homozygous Mel1b-mutant mice on the 129/sv genetic background.

Cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation.

Pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating peptide (PACAP) is a transmitter of the retinohypothalamic tract, the pathway that conveys light-dark information from the retina to the SCN (17). PACAP appears to modulate the effects of glutamate on the SCN (17, 40). In vitro application of PACAP to SCN slices induces phosphorylation of CREB on serine residue 133 (20, 40, 41). Phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) is thought to play an important role in the photic regulation of gene expression in the SCN, including the light-induced expression of c-fos and the mPeriod genes (14, 38, 40). Melatonin reduces PACAP-induced pCREB immunoreactivity in SCN slices in a dose-dependent manner (20, 40, 41, 42). Melatonin may thus subtly modulate photic sensitivity of the SCN circadian clock.

Melatonin inhibition of the PACAP-induced CREB phosphorylation state was studied as previously described (41). Briefly, 400-μm coronal brain slices containing the SCN were collected 2 to 6 h after lights-on and maintained in oxygenated medium (145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.8 MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM glucose [pH 7.35]). At the time corresponding to Zeitgeber Time 10 (ZT10, e.g., 10 h after lights-on in the colony room), slices were treated with PACAP (100 nM) or vehicle. Slices were pretreated with melatonin (1 or 100 nM) or vehicle for 15 min prior to PACAP application. Fifteen minutes after PACAP application, slices were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Slices were fixed for 12 to 16 h and then cryo-protected (20% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline) and sectioned at 14-μm thickness on a cryostat. Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides and stored at −20°C until processed for immunohistochemical detection of CREB phosphorylated at serine 133 (pCREB). pCREB was detected by use of a commercially available, polyclonal antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.) at a dilution of 1:1,000. Immunoreaction was visualized with a standard avidin-biotin labeling method (Vector Labs, Burlingame, Calif.) with diaminobenzidine as a chromogen.

Semiquantitative analysis was performed as previously described (41). Briefly, images were digitized (VIDAS, Kontron, Germany), and background staining was defined as the lower threshold. Within the area of the SCN, all cell nuclei showing a pCREB immunoreaction exceeding the threshold were marked. Immunoreactive nuclei were then counted in three sections per animal in a blind manner. The average of six values (number of immunoreactive nuclei per unilateral SCN per 14-μm section) was calculated for each animal.

It is not known whether melatonin alters the number of nuclei immunoreactive for pCREB by a reduction in the rate of phosphorylation of CREB or by activation of a phosphatase. In this report, “CREB phosphorylation” is used to indicate the static state of CREB phosphorylation (e.g., density of pCREB-immunoreactive nuclei), not the rate at which CREB is phosphorylated.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The cDNA sequence for the mouse Mel1b receptor that was determined in this study has been deposited in GenBank (accession number AY145850).

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of the mouse Mel1b receptor cDNA.

The mouse Mel1b receptor cDNA sequence was determined from genomic DNA and confirmed by amplification of the receptor cDNA from brain RNA (see Materials and Methods for discussion of discrepancies between our sequence and other database entries).

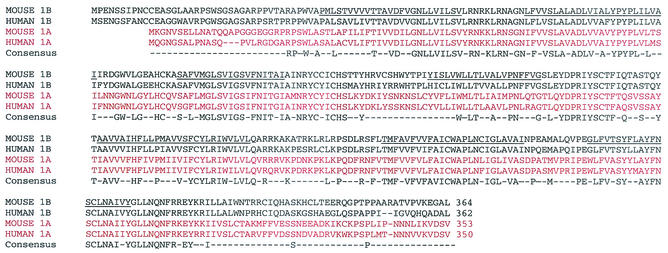

The deduced amino acid sequence of the Mel1b receptor has features shared by other members of the melatonin receptor subfamily of G protein-coupled receptors (Fig. 2). Specifically, the amino acid sequence of the mouse Mel1b receptor is highly related to the human Mel1b receptor, with which it shares 79% identity. The other closely related sequences identified by BLAST searches of the GenBank database are fragments of the Mel1b receptor cDNA from other species, including the Northern pike Mel1b receptor cDNA (12). Amino acid identity of the mouse Mel1a and Mel1b receptors is 50.8%.

FIG. 2.

The mouse Mel1b receptor sequence. The sequence of the mouse Mel1b receptor has been aligned with other members of the melatonin receptor gene family: mouse Mel1b (present work), human Mel1b (30), mouse Mel1a (34) (NP_032665), and human Mel1a receptor (29) (NP_005949). Putative transmembrane domains are indicated by underlining in the sequence for the mouse Mel1b receptor. Gaps introduced to optimize alignment are indicated by dashes. Consensus sequence is defined as residues that are identical in all four of the sequences shown.

The mouse Mel1b receptor sequence also has several features conserved in the melatonin receptor family within the superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors. A highly conserved sequence just downstream from the third transmembrane domain (NRYC[C/Y]ICHS) is distinctive; most other receptor families have DRY or ERY in place of NRY (33, 45). In transmembrane domain 7, the melatonin receptor family shares a characteristic motif (NA[I/V][I/V]Y) rather than NPXXY. The presence of potential a N-linked glycosylation site in the amino-terminal, putative extracellular domain of the protein is also a common feature of the melatonin receptor family. Finally, with respect to gene structure, the location of the splice site between exons 1 and 2 is also conserved among all mammalian melatonin receptor genes that have been examined (32, 34, 47).

To determine the relative affinity and specificity of mouse melatonin receptors, the characteristics of the mouse Mel1a and Mel1b receptor cDNAs were examined in parallel. 125I-MEL binding to transfected COS7 cells revealed that the affinity of the mouse Mel1b receptor is significantly lower than the affinity of the mouse Mel1a receptor (Mel1b, Kd (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) = 199.9 ± 13.4 pM [n = 4]; Mel1a, KD = 59.3 ± 18.3 pM [n = 2]). Competition experiments with several drugs revealed that the rank order of potency was as expected for a member of the melatonin receptor gene family, e.g., 2-iodomelatonin > melatonin > 6-chloromelatonin ≫ N-acetylserotonin (Table 1). The relative affinity of the receptor subtypes as well as the rank order of drug potency for inhibiting 125I-MEL binding are similar to the characteristics of the human Mel1a and Mel1b receptors (30).

TABLE 1.

Inhibition constants for mouse Mel1a and Mel1b receptor cDNAsa

| Compound |

Ki (no. of experiments) for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Mel1a | Mel1b | |

| 2-Iodomelatonin | 0.045 ± 0.005 (4) | 0.159 ± .017 (4) |

| Melatonin | 0.438 ± 0.169 (3) | 2.853 ± 0.665 (3) |

| 6-Chloromelatonin | 4.053 ± 1.371 (3) | 8.903 ± 1.640 (3) |

| N-acetylserotonin | 638 (1) | 296 (1) |

Inhibition constants (Ki values) are expressed as means ± SEM, in nanomolar concentrations.

It is noteworthy that the mouse Mel1b receptor encodes a functional receptor, as inferred from its sequence and confirmed in radioreceptor assays. This is in contrast to the Mel1b receptor gene in several hamster species, including Siberian and Syrian hamsters, in which nonsense mutations disrupt the receptor cDNA (see reference 47 and GenBank accession number AY145849).

Targeted disruption of the mouse Mel1b receptor gene.

Mice with targeted disruption of the Mel1b receptor gene are viable and fertile. This is not unexpected; most inbred strains of mice do not produce melatonin as a result of genetic defects in the synthetic enzymes (11, 35), and removal of the pineal gland, the source of circulating melatonin, does not have major physiological effects (except in species in which melatonin is involved in the seasonal regulation of reproduction).

Observations of locomotor activity rhythms of Mel1b receptor-deficient mice and wild-type controls placed in constant darkness revealed no robust circadian phenotype; e.g., activity rhythms persisted in homozygous Mel1b receptor-deficient mice in constant conditions, with a period length similar to that observed in controls (data not shown). Preliminary attempts to use daily or repeated daily injections of melatonin to phase shift the locomotor activity rhythm of wild-type mice were unsuccessful, preventing us from employing an in vivo assay of melatonin receptor function. Instead, in vitro assays of melatonin receptor function were employed.

Melatonin inhibits multiunit activity via the Mel1a receptor.

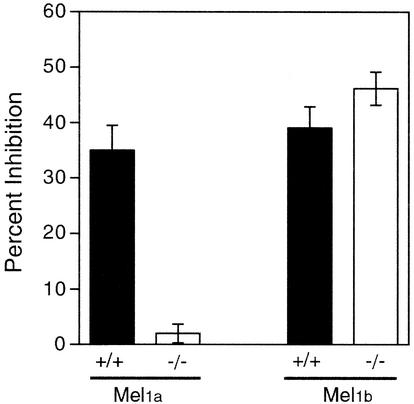

Inhibition of SCN multiunit activity by melatonin was unaffected in mice with targeted disruption of the Mel1b receptor (Fig. 3). In contrast, the acute suppressive effect of melatonin was absent in mice homozygous for targeted disruption of the Mel1a receptor (23; [data replotted for comparison in Fig. 3]). Thus, the Mel1a receptor alone appears to mediate the suppressive effect of melatonin on SCN neuronal firing rate.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of SCN multiunit activity by melatonin. Inhibition of SCN electrical activity by melatonin (0.1 to 100 nM) was assessed during midday. Data are plotted as the percent inhibition of electrical activity observed at the 100 nM dose relative to the level of electrical activity from the same slice exposed to vehicle. The left set of bars shows that the inhibition of SCN electrical activity is absent in Mel1a receptor-deficient (−/−) mice (data replotted from reference 23; sample sizes 7 to 11 per group). Right bars show inhibition of SCN activity in experiments conducted for this study, using Mel1b receptor-deficient mice (−/−) (n = 6) and wild-type control (+/+) (n = 11) mice. The inhibition of electrical activity in each group was significant (P < 0.0001, one-sample t tests, versus 0% inhibition), and there was no significant difference between the Mel1b −/− and Mel1b +/+ groups (t test, P = 0.2).

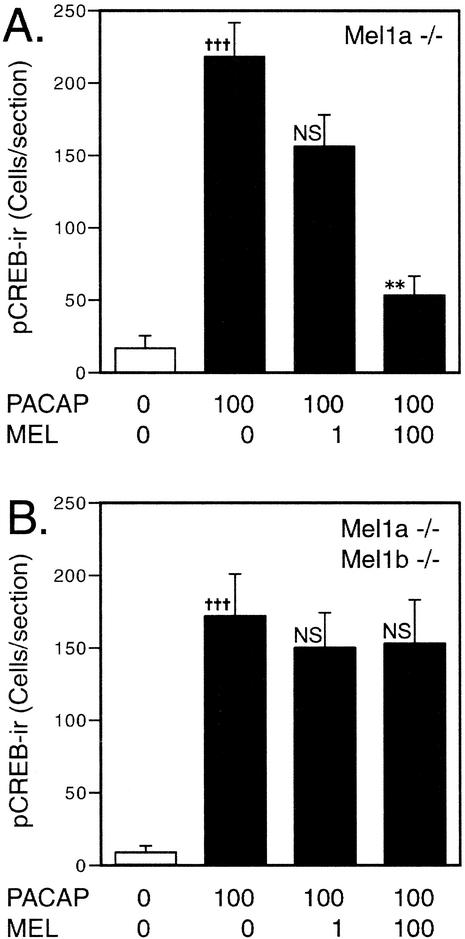

Both melatonin receptor subtypes contribute to regulation of CREB phosphorylation.

Previous studies have shown that melatonin reduces the levels of PACAP-induced CREB phosphorylation at low concentrations (20, 40, 41). In wild-type mice, physiological concentrations of melatonin (≤1 nM) inhibit the level of phosphorylated CREB by >70%. In mice with targeted disruption of the Mel1a melatonin receptor, the response to 1 nM melatonin is absent, but a residual effect of melatonin is apparent at higher melatonin concentrations (Fig. 4A, consistent with previously published results [41]). This higher-threshold response to melatonin appears to be mediated by the Mel1b receptor, as the Mel1b-preferring antagonist, 4P-PDOT (8), blocks the high-threshold response (41). In mice with targeted disruption of both Mel1a and Mel1b receptor genes, the residual response to high concentrations of melatonin is completely absent (Fig. 4B). These data indicate a dual regulation of the CREB phosphorylation state in the SCN: the Mel1a receptor mediates responses to low concentrations of the hormone, while the residual response at higher concentrations is mediated by the Mel1b receptor. The presence of a functional Mel1a receptor that would mediate low-threshold responses precluded assessing the effect of disruption of the Mel1b receptor alone.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of CREB phosphorylation levels by melatonin. Semiquantitative densitometric analysis shows that melatonin reduces the number of pCREB-immunoreactive nuclei in PACAP-treated SCN slices. Values represent labeled nuclei per unilateral SCN and are the mean ± SEM for four to five animals per group. In wild-type mice, melatonin (1 nM) reduces PACAP-induced CREB phosphorylation by >70% (41). In contrast, a 1 nM concentration had no significant effect on mice with targeted disruption of the Mel1a melatonin receptor (Mel1a −/−) (A). At higher melatonin concentrations (100 nM), a more complete suppression occurs even in mice with disruption of the Mel1a receptor subtype (A) (far right). This residual, higher-threshold response is absent in mice with targeted disruption of both the Mel1a and Mel1b receptors (B). +++, significant difference between vehicle control and PACAP treatment (P < 0.002, t test); ∗∗, significant difference versus PACAP group (P < 0.01, Dunnett's test); NS, not significantly different from PACAP group (P > 0.05, Dunnett's test).

DISCUSSION

Melatonin has subtle actions on circadian rhythmicity in mice and in other mammals (46). Mice with targeted disruption of either Mel1a or Mel1b receptor subtype, or the double mutants, do not have a striking overt phenotype. Examination of melatonin receptor-mediated responses does reveal a functional effect of each of the receptor subtypes, however. The Mel1a receptor is necessary for the suppressive effect of melatonin on SCN neuronal firing (23). Targeted disruption of the Mel1b receptor did not alter this response to melatonin. With respect to inhibition of the PACAP-induced CREB phosphorylation state, melatonin acts through the Mel1a receptor at low concentrations of the hormone (41) (present results). An effect of higher concentrations of melatonin is apparent in Mel1a receptor-deficient mice, and this response is blocked by treatment with the Mel1b receptor antagonist, 4P-PDOT (41). Consistent with this dual regulation, we report here that the SCN of Mel1a-Mel1b double-mutant mice is completely unresponsive to melatonin, even at the higher (100 nM) melatonin concentrations.

One of the in vitro assays used previously to assess the effects of melatonin on the circadian clock involves monitoring the effect of melatonin on the phase of single-unit firing rate rhythms in SCN slices (19, 23, 26, 47). Liu et al. (23) found that melatonin and 2-iodomelatonin phase-shifted the circadian rhythm of SCN single-unit activity even in mice with targeted disruption of the Mel1a receptor, although the magnitude of response was lower in the Mel1a receptor-deficient mice at low ligand concentrations. The response persisting in Mel1a receptor-deficient mice was mediated by a pertussis toxin-sensitive mechanism, indirectly implicating Mel1b receptors as mediating the higher-threshold response. More recently, Hunt et al. (19) reported that the Mel1b receptor subtype mediates the phase-shifting effect of melatonin in the rat SCN, based on studies using subtype-selective antagonists. In contrast, SCN slices from hamsters lacking a functional Mel1b receptor (due to a naturally occurring nonsense mutation) respond to melatonin with phase shifts in single-unit activity (47). These diverse results from the single-unit assay indicate either that there are pronounced species differences in the melatonin receptor subtype mediating the phase shifting response or, more likely, that there is functional redundancy between the receptor subtypes.

While this assay system has been used successfully by our associates and others in the past, in preliminary studies we were unable to obtain reliable single-unit activity rhythms, even with commercially reared wild-type mice, at the time we attempted to examine the responses of Mel1b receptor-deficient mice (C. Liu and S. M. Reppert, unpublished data). In the absence of a robust rhythm with clearly defined phase, assessment of the impact of melatonin on circadian phase was not possible.

We were also unable, in preliminary experiments, to demonstrate a consistent effect of melatonin on locomotor activity rhythms in vivo, even in wild-type mice with the C3H genetic background. This strain has previously been reported to exhibit phase shifts in response to melatonin treatment (2, 3, 9). The mean phase shift occurring in the paradigm described by Dubocovich and colleagues is a less than 1.0-h total shift with daily injections of melatonin for 3 days. Behavioral arousal (such as would occur coincident with handling the animal for injection) has an effect on the rodent circadian system that appears to be as robust as the effect of melatonin (18, 28). In our hands, melatonin injection paradigms did not elicit consistently detectable phase shifts in mice. We were thus unable to use the mutant mice to directly test the hypothesis (9) that the Mel1b receptor mediates behavioral phase shifts.

Data from other systems suggest that both Mel1a and Mel1b receptors contribute to responses to the hormone. Vascular responses to melatonin occurring at low concentrations are mediated primarily by the Mel1a receptor, with a Mel1b-mediated response occurring at higher concentrations (6, 37). This directly parallels our findings regarding the dose-related inhibition of PACAP-induced CREB phosphorylation in the SCN. The acute suppressive effect of melatonin on SCN neuronal firing is mediated by the Mel1a receptor. The Mel1b receptor appears to mediate inhibition of firing in the rat hippocampus, which, unlike the mouse hippocampus, has a significant level of melatonin receptor binding (44). A melatonin-regulated rhythm in mPeriod1 gene expression in the pars tuberalis of the pituitary is abolished by removal of the pineal gland in hamsters (27); the absence of a functional Mel1b melatonin receptor gene in this species implicates the Mel1a receptor. Consistent with this proposal, pinealectomy or targeted disruption of the Mel1a receptor gene in mice that have rhythmic pineal melatonin synthesis disrupts rhythmic mPer1 expression in the pars tuberalis (42). These findings suggest that the expression of melatonin receptor subtypes varies by tissue and indicate the possibility of functional redundancy when the receptor subtypes are coexpressed.

In summary, targeted disruption of the Mel1b receptor does not have a profound impact on the circadian system of mice. Our data from examining melatonin inhibition of the level of CREB phosphorylation in PACAP-treated SCN slices indicate that the Mel1a receptor mediates the majority of this response to the hormone. At higher melatonin concentrations, a residual impact of melatonin, acting via the Mel1b receptor, is apparent. This difference in the relative contribution of the receptor subtypes is likely not due to differences in the affinity of the receptors per se, but instead may derive from differences in the levels of receptor expression directed by the two genes or by differences in coupling to second messenger pathways. The Mel1a receptor accounts for all the melatonin receptor binding detected in mouse brain by in vitro autoradiography (23). The Mel1a receptor, being much more highly expressed, may mediate most responses to the hormone in mice. The Mel1b receptor can also contribute to responses in those tissues in which it is expressed. The availability of mice with targeted disruption of Mel1a, Mel1b, and both receptor subtypes will allow a genetic approach to dissection of additional melatonin receptor-mediated responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chen Liu, Donald Hodges, and Stefanie Rassnick for assistance with preliminary studies and Camala Capodice and Christopher Lambert for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (DK42125 to S.M.R. and AG09975 to D.R.W)., the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to J.H.S and C.V.G.), the Paul und Ursula Klein-Stiftung and the Heinrich und Fritz Reise-Stiftung (to J.H.S), and a sponsored research agreement from Bristol-Myers Squibb. X.J. was supported in part by NIH Postdoctoral fellowship F32 MH12067. C.V.G. was supported in part by the Emmy-Noether Programm of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartness, T. J., E. L. Bittman, M. H. Hastings, J. B. Powers, and B. D. Goldman. 1993. Timed melatonin infusion paradigm for melatonin delivery: what has it taught us about the melatonin signal, its reception, and the photoperiodic control of seasonal responses? J. Pineal Res. 15:161-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benloucif, S., M. I. Masana, K. Yun, and M. L. Dubocovich. 1999. Interactions between light and melatonin on the circadian clock of mice. J. Biol. Rhythms 14:281-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benloucif, S., and M. L. Dubocovich. 1996. Melatonin and light induce phase shifts of circadian activity rhythms in the C3H/HeN mouse. J. Biol. Rhythms 11:113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassone, V. M. 1990. Effects of melatonin on vertebrate circadian systems. Trends Neurosci. 13:457-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng, Y., and W. H. Prusoff. 1973. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 22:3099-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doolen, S., D. N. Krause, M. L. Dubocovich, and S. P. Duckles. 1998. Melatonin mediates two distinct responses in vascular smooth muscle. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 345:67-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drew, J. E., P. Barrett, L. M. Williams, S. Conway, and P. J. Morgan. 1998. The ovine melatonin-related receptor: cloning and preliminary distribution and binding studies. J. Neuroendocrinol. 10:651-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubocovich, M. L., M. I. Masana, S. Jacob, and D. M. Sauri. 1997. Melatonin receptor antagonists that differentiate between the human Mel1a and Mel1b recombinant subtypes are used to assess the pharmacological profile of the rabbit retina ML1 presynaptic heteroceptor. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 355:365-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubocovich, M. L., K. Yun, W. M. Al-Ghoul, S. Benloucif, and M. I. Masana. 1998. Selective MT2 melatonin receptor antagonists block melatonin-mediated phase advances of circadian rhythms. FASEB J. 12:1211-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubocovich, M. L., D. P. Cardinali, P. Delagrange, D. N. Krause, A. D. Strosberg, D. Sugden, and F. D. Yocca. 2000. The IUPHAR compendium of receptor characterisation and classification, 2nd ed., p. 187-193. IUPHAR Media, London, United Kingdom.

- 11.Ebihara, S., T. Marks, D. J. Hudson, and M. Menaker. 1986. Genetic control of melatonin synthesis in the pineal gland of the mouse. Science 231:491-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaildrat, P., F. Becq, and J. Falcon. 2002. First cloning and functional characterization of a melatonin receptor in fish brain: a novel one? J. Pineal Res. 32:74-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganguly, S., S. L. Coon, and D. C. Klein. 2002. Control of melatonin synthesis in the mammalian pineal gland: the critical role of serotonin acetylation. Cell Tissue Res. 309:127-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gribkoff, V. K., R. L. Pieschl, T. A. Wisialowski, A. N. van den Pol, and F. D. Yocca. 1998. Phase shifting of circadian rhythms and depression of neuronal activity in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus by neuropeptide Y: mediation by different receptor subtypes. J. Neurosci. 18:3014-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginty, D. D., J. M. Kornhauser, M. A. Thompson, H. Bading, K. E. Mayo, J. S. Takahashi, and M. E. Greenberg. 1993. Regulation of CREB phosphorylation in the suprachiasmatic nucleus by light and a circadian clock. Science 260:238-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gubitz, A. K., and S. M. Reppert. 1999. Assignment of the melatonin-related receptor to human chromosome X (GPR50) and mouse chromosome X (Gpr50). Genomics 55:248-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hannibal, J. 2002. Neurotransmitters of the retinohypothalamic tract. Cell Tissue Res. 309:73-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hastings, M. H., S. M. Mead, R. R. Vindlacheruvu, F. J. Ebling, E. S. Maywood, and J. Grosse. 1992. Non-photic phase shifting of the circadian activity rhythm of Syrian hamsters: the relative potency of arousal and melatonin. Brain Res. 591:20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt, A. E., W. M. Al-Ghoul, M. U. Gillette, and M. L. Dubocovich. 2001. Activation of MT2 melatonin receptors in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus phase advances the circadian clock. Am. J. Physiol. 280:C110-C118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopp, M., H. Meissl, and H. W. Korf. 1997. The pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-induced phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB (cAMP response element binding protein) in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus is inhibited by melatonin. Neurosci. Lett. 227:145-148.0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lewy, A. J., S. Ahmed, J. M. Jackson, and R. L. Sack. 1992. Melatonin shifts human circadian rhythms according to a phase-response curve. Chronobiol. Int. 9:380-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewy, A. J., V. K. Bauer, B. P. Hasler, A. R. Kendall, M. L. Pires, and R. L. Sack. 2001. Capturing the circadian rhythms of free-running blind people with 0.5 mg melatonin. Brain Res. 918:96-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, C., D. R. Weaver, X. Jin, L. P. Shearman, R. L. Pieschl, V. K. Gribkoff, and S. M. Reppert. 1997. Molecular dissection of two distinct actions of melatonin on the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Neuron 19:91-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malpaux, B., M. Migaud, H. Tricoire, and P. Chemineau. 2001. Biology of mammalian photoperiodism and the critical role of the pineal gland and melatonin. J. Biol. Rhythms 16:336-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margraf, R. R., and G. R. Lynch. 1993. Melatonin injections affect circadian behavior and SCN neurophysiology in Djungarian hamsters. Am. J. Physiol. 264:R615-R621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McArthur, A. J., A. E. Hunt, and M. U. Gillette. 1997. Melatonin action and signal transduction in the rat suprachiasmatic circadian clock: activation of protein kinase C at dusk and dawn. Endocrinology 138:627-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messager, S., M. L. Garabette, M. H. Hastings, and D. G. Hazlerigg. 2001. Tissue-specific abolition of Per1 expression in the pars tuberalis by pinealectomy in the Syrian hamster. NeuroReport 12:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reebs, S. G., and N. Mrosovsky. 1989. Effects of induced wheel running on the circadian activity rhythms of Syrian hamsters: entrainment and phase response curve. J. Biol. Rhythms 4:39-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reppert, S. M., D. R. Weaver, and T. Ebisawa. 1994. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian melatonin receptor that mediates reproductive and circadian responses. Neuron 13:1177-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reppert, S. M., C. Godson, C. D. Mahle, D. R. Weaver, S. A. Slaugenhaupt, and J. F. Gusella. 1995. Molecular characterization of a second melatonin receptor expressed in human retina and brain: the Mel1b-melatonin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8734-8738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reppert, S. M., D. R. Weaver, V. M. Cassone, C. Godson, and L. F. Kolakowski, Jr. 1995. Melatonin receptors are for the birds: molecular analysis of two receptor subtypes differentially expressed in chick brain. Neuron 15:1003-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reppert, S. M., D. R. Weaver, T. Ebisawa, C. D. Mahle, and L. F. Kolakowski, Jr. 1996. Cloning of a melatonin-related receptor from human pituitary. FEBS Lett. 386:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reppert, S. M., D. R. Weaver, and C. Godson. 1996. Melatonin receptors step into the light: cloning and classification of subtypes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 17:100-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roca, A. L., C. Godson, D. R. Weaver, and S. M. Reppert. 1997. Structure, characterization, and expression of the gene encoding the mouse Mel1a melatonin receptor. Endocrinology 137:3469-3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roseboom, P. H., M. A. A. Namboodiri, D. B. Zimonjic, N. C. Popescu, I. R. Rodriguez, J. A. Gastel, and D. C. Klein. 1998. Natural melatonin ′knockdown' in C57BL/6J mice: rare mechanism truncates serotonin N-acetyltransferase. Mol. Brain Res. 63:189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rusak, B., and G. D. Yu. 1993. Regulation of melatonin-sensitivity and firing-rate rhythms of hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons: pinealectomy effects. Brain Res. 602:200-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ting, K. N., N. A. Blaylock, and D. Sugden. 1999. Molecular and pharmacological evidence for MT1 receptor subtypes in tail artery of juvenile Wistar rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 127:987-995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Travnickova-Bendova, Z., N. Cermakian, S. M. Reppert, P. Sassone-Corsi. 2002. Bimodal regulation of mPeriod promoters by CREB-dependent signaling and CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7728-7733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viswanathan, N., and F. C. Davis. 1997. Single prenatal injections of melatonin or the D1-dopamine receptor agonist SKF 38393 to pregnant hamsters sets the offsprings' circadian rhythms to phases 180 degrees apart. J. Comp. Physiol. [A] 180:339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Gall, C., G. Duffield, M. Hastings, M. D. Kopp, F. Dehghani, H. W. Korf, and J. H. Stehle. 1998. CREB in the mouse SCN: a molecular integrator coding the phase adjusting stimuli of light, glutamate, PACAP and melatonin for clockwork access. J. Neurosci. 18:10389-10397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Gall, C., D. R. Weaver, M. Kock, H. W. Korf, and J. H. Stehle. 2000. Melatonin limits transcriptional impact of phosphoCREB in the mouse SCN via the Mel1a receptor. NeuroReport 11:1803-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Gall, C., M. L. Garabette, C. A. Kell, S. Frenzel, F. Dehghani, P. M. Schumm-Draeger, D. R. Weaver, H. W. Korf, M. H. Hastings, and J. H. Stehle. 2002. Rhythmic gene expression in pituitary depends on heterologous sensitization by the neurohormone melatonin. Nat. Neurosci. 5:234-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Gall, C., J. H. Stehle, and D. R. Weaver. 2002. Mammalian melatonin receptors: molecular biology and signal transduction. Cell Tissue Res. 309:151-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wan, Q., H. Y. Man, F. Liu, J. Braunton, N. B. Niznik, S. F. Pang, G. M. Brown, and Y. T. Wang. 1999. Differential modulation of GABAA receptor function by Mel1a and Mel1b receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 2:401-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson, S., and S. Arkinstall. 1994. The G-protein linked receptor factsbook. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 46.Weaver, D. R. 1999. Melatonin and circadian rhythmicity in vertebrates. Physiological roles and pharmacological effects, p. 197-262 In F. W. Turek and P. C. Zee (ed.), Regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 47.Weaver, D. R., C. Liu, and S. M. Reppert. 1996. Nature's knockout: the Mel1b receptor is not necessary for circadian or reproductive responses in Siberian hamsters. Mol. Endocrinol. 10:1478-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]